Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Center of population

View on Wikipedia

In demographics, the center of population (or population center) of a region is a geographical point that describes a centerpoint of the region's population. There are several ways of defining such a "center point", leading to different geographical locations; these are often confused.[1]

Definitions

[edit]Three commonly used (but different) center points are:

- the mean center, also known as the centroid or center of gravity;

- the median center, which is the intersection of the median longitude and median latitude;

- the geometric median, also known as Weber point, Fermat–Weber point, or point of minimum aggregate travel.

A further complication is caused by the curved shape of the Earth. Different center points are obtained depending on whether the center is computed in three-dimensional space, or restricted to the curved surface, or computed using a flat map projection.

Mean center

[edit]The mean center, or centroid, is the point on which a rigid, weightless map would balance perfectly, if the population members are represented as points of equal mass.

Mathematically, the centroid is the point to which the population has the smallest possible sum of squared distances. It is easily found by taking the arithmetic mean of each coordinate. If defined in three-dimensional space, the centroid of points on the Earth's surface is actually inside the Earth. This point could then be projected back to the surface. Alternatively, one could define the centroid directly on a flat map projection; this is, for example, the definition that the US Census Bureau uses.

Contrary to a common misconception, the centroid does not minimize the average distance to the population. That property belongs to the geometric median.

Median center

[edit]The median center is the intersection of two perpendicular lines, each of which divides the population into two equal halves.[2] Typically these two lines are chosen to be a parallel (a line of latitude) and a meridian (a line of longitude). In that case, this center is easily found by taking separately the medians of the population's latitude and longitude coordinates. John Tukey called this the cross median.[3]

Geometric median

[edit]The geometric median is the point to which the population has the smallest possible sum of distances (or equivalently, the smallest average distance). Because of this property, it is also known as the point of minimum aggregate travel. Unfortunately, there is no direct closed-form expression for the geometric median; it is typically computed using iterative methods.[citation needed]

Determination

[edit]In practical computation, decisions are also made on the granularity (coarseness) of the population data, depending on population density patterns or other factors. For instance, the center of population of all the cities in a country may be different from the center of population of all the states (or provinces, or other subdivisions) in the same country. Different methods may yield different results.

Practical uses for finding the center of population include locating possible sites for forward capitals, such as Brasília, Astana or Austin, and, along the same lines, to make tax collection easier. Practical selection of a new site for a capital is a complex problem that depends also on population density patterns and transportation networks.

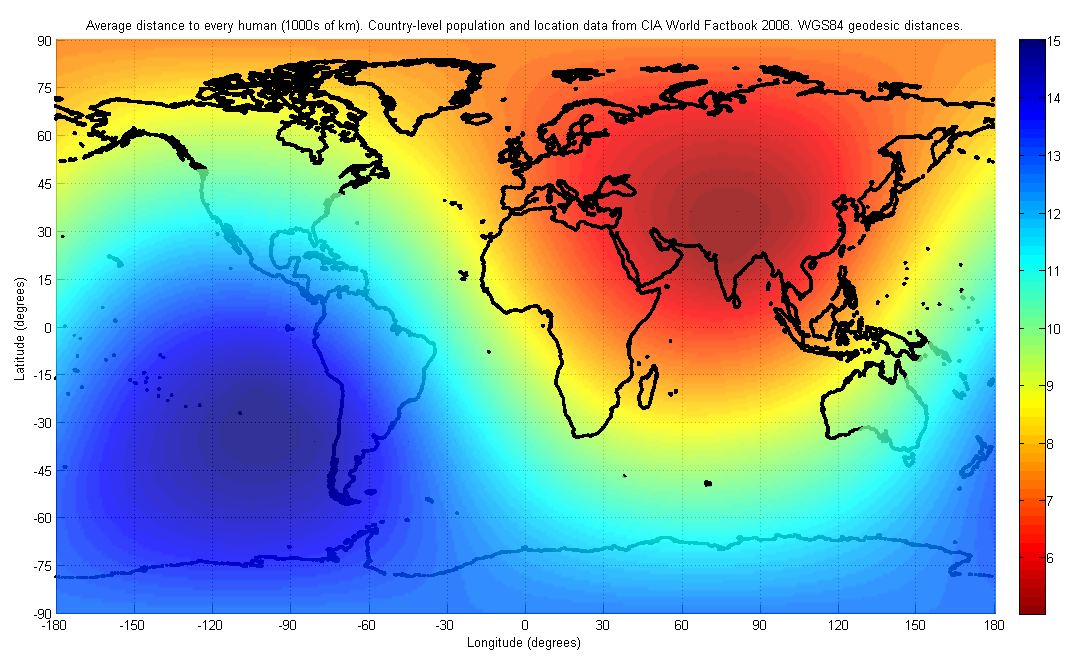

World

[edit]It is important to use a method that does not depend on a two-dimensional projection when dealing with the entire world. In a study from the Institut national d'études démographiques,[4] the solution methodology deals only with the globe. As a result, the answer is independent of which map projection is used or where it is centered. As described above, the exact location of the center of population will depend on both the granularity of the population data used, and the distance metric. With geodesic distances as the metric, and a granularity of 1,000 kilometers (600 mi), meaning that two population centers within 1000 km of each other are treated as part of a larger common population center of intermediate location, the world's center of population is found to lie "at the crossroads between China, India, Pakistan and Tajikistan" with an average distance of 5,200 kilometers (3,200 mi) to all humans.[4] The data used in the reference support this result to a precision of only a few hundred kilometers, hence the exact location is not known.

Another analysis, using city-level population data, found that the world's center of population is close to Almaty, Kazakhstan.[5]

By country

[edit]Antigua and Barbuda

[edit]In 2011, the center of population of Antigua (excluding Barbuda) was located in St. Claire.[6]

Australia

[edit]Australia's population centroid is in central New South Wales. By 1996, it had moved only a little to the north-west since 1911.[7] It moved only 1.4 km north in 2022 from the previous year[8] and in 2023 moved 1.9 km west compared to 2022, located 40 km east of Ivanhoe.[9]

Canada

[edit]In Canada, a 1986 study placed the point of minimum aggregate travel just north of Toronto in the city of Richmond Hill, and moving westward at a rate of approximately 2 meters per day.[10]

China

[edit]China's population centroid has wandered within southern Henan from 1952 to 2005. Incidentally, the two end point dates are remarkably close to each other.[11] China also plots its economic centroid or center of economy/GDP, which has also wandered, and is generally located at the eastern Henan borders.[11]

Estonia

[edit]

The center of population of Estonia was on the northwestern shore of Lake Võrtsjärv in 1913 and moved an average of 6 km northwest with every decade until the 1970s. The higher immigration rates during the late Soviet occupation to mostly Tallinn and Northeastern Estonia resulted the center of population moving faster towards north and continuing urbanization has seen it move northwest towards Tallinn since the 1990s. The center of population according to the 2011 census was in Jüri, just 6 km southeast from the border of Tallinn.[12]

Finland

[edit]In Finland, the point of minimum aggregate travel is located in the former municipality of Hauho.[13] It is moving slightly to the south-west-west every year because people are moving out of the peripheral areas of northern and eastern Finland.

Germany

[edit]In Germany, the centroid of the population is located in Spangenberg, Hesse, close to Kassel.[14]

Great Britain

[edit]The centre of population in Great Britain did not move significantly in the 20th century. In 1901, it was in Rodsley, Derbyshire and in 1911 in Longford. In 1971 it was at Newhall, Swadlincote, South Derbyshire and in 2000, it was in Appleby Parva, Leicestershire.[15][16] Using the 2011 census the population centre can be calculated at Snarestone, Swadlincote.[17]

Ireland

[edit]The center of population of the entire island of Ireland is located near Kilcock, County Kildare. This is significantly further east than the Geographical centre of Ireland, reflecting the disproportionately large cities of the east of the island (Belfast and Dublin).[18] The center of population of the Republic of Ireland is located southwest of Edenderry, County Offaly.[19]

Japan

[edit]The centroid of population of Japan is in Gifu Prefecture, almost directly north of Nagoya city, and has been moving east-southeast for the past few decades.[20] Since 2010, the only large regions in Japan with significant population growth have been in Greater Tokyo and Okinawa Prefecture.

New Zealand

[edit]

In June 2008, New Zealand's median center of population was located near Taharoa, around 100 km (65 mi) southwest of Hamilton on the North Island's west coast.[21] In 1900 it was near Nelson and has been moving steadily north (towards Auckland, the country's most populous city) ever since.[22]

Sweden

[edit]The demographical center of Sweden (using the median center definition) is Hjortkvarn in Hallsberg Municipality, Örebro county. Between the 1989 and 2007 census the point moved a few kilometres to the south, due to a decreasing population in northern Sweden and immigration to the south.[23]

Russia

[edit]The center of population in the Russian Federation is calculated by A. K. Gogolev to be at 56°26′N 53°04′E / 56.433°N 53.067°E as of 2010, 46.5 km (28.9 mi) south-southwest of Izhevsk.[24]

Taiwan

[edit]The center of population of Taiwan is located in Heping District, Taichung.[25]

United States

[edit]The mean center of the United States population (using the centroid definition) has been calculated for each U.S. Census since 1790. Over the last two centuries, it has progressed westward and, since 1930, southwesterly, reflecting population drift. For example, in 2010, the mean center was located near Plato, Missouri, in the south-central part of the state, whereas, in 1790, it was in Kent County, Maryland, 47 miles (76 km) east-northeast of the future federal capital, Washington, D.C.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kumler, Mark P.; Goodchild, Michael F. (1992). "The population center of Canada – Just north of Toronto?!?". In Janelle, Donald G. (ed.). Geographical snapshots of North America: commemorating the 27th Congress of the International Geographical Union and Assembly. pp. 275–279.

- ^ "Centers of Population Computation for the United States, 1950-2010" (PDF). Washington, DC: Geography Division, U.S. Census Bureau. March 2011.

- ^ Tukey, John (1977). Exploratory Data Analysis. Addison-Wesley. p. 668. ISBN 9780201076165.

- ^ a b Claude Grasland and Malika Madelin (May 2001). "The unequal distribution of population and wealth in the world" (PDF). Population et SociétéS. 368. Institut national d'études démographiques: 1–4. ISSN 0184-7783.

- ^ "Center of World Population". City Extremes. 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ Joseph, Geraldine (17 April 2025). "Centre of population of Antigua, 2011". Axarplex. Retrieved 1 May 2025.

- ^ "Figure 15: Shifts in the Australian Population Centroid*, 1911–1996". Parliament of Australia Parliamentary Library. Archived from the original on 19 August 2000. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- ^ "Regional population". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 20 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ "Regional population". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 26 March 2024. Retrieved 3 September 2024.

- ^ "The Population Center of Canada – Just North of Toronto?!?" (PDF). Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ a b Fan, Jie; Tao, Anjun; LV, Chen (2010). "The Coupling Mechanism of the Centroids of Economic Gravity and Population Gravity and Its Effect on the Regional Gap in China". Progress in Geography. 29 (1): 87–95. doi:10.11820/dlkxjz.2010.01.012. ISSN 1007-6301.

- ^ Haav, Mihkel (2010) - "Eesti dünaamika 1913-1999"

- ^ Uusirauma.fi[permanent dead link] Kaupunkilehti Uusi Rauma 03.08.2009 Päivän kysymys? Missä Rauman keskipiste? (in Finnish)

- ^ Dradio.de Archived 24 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- ^ "News Item". University of Leeds. Archived from the original on 3 October 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- ^ "Population Centre". Appleby Magna & Appleby Parva. Archived from the original on 23 November 2007. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Population Centre of the island of Ireland [2100x2000] [OC]".

- ^ "Population Centre of Ireland".

- ^ "Our Country's Center of Population (我が国の人口重心)". Stat.go.jp. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "Subnational Population Estimates: At 30 June 2008 -- Commentary". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ "Bridget Williams Books".

- ^ "Sweden's demographic centre, SCB.se, 2008-03-18". Scb.se. 18 March 2008. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ Сайт "Встарь, или Как жили люди"

- ^ "Re: [人口地理] 臺灣人口重心分佈".

Sources

[edit]- Bellone F. and Cunningham R. (1993). "All Roads Lead to... Laxton, Digby and Longford." Statistics Canada 1991 Census Short Articles Series.