Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Charles II of Navarre

View on Wikipedia

Charles II (French: Charles, Spanish: Carlos, Basque: Karlos, 10 October 1332 – 1 January 1387), known as the Bad,[a] was King of Navarre beginning in 1349, as well as Count of Évreux beginning in 1343, holding both titles until his death in 1387.

Key Information

Besides the Kingdom of Navarre nestled in the Pyrenees, Charles had extensive lands in Normandy, inherited from his father, Count Philip of Évreux, and his mother, Queen Joan II of Navarre, who had received them as compensation for resigning her claims to France, Champagne, and Brie in 1328. Thus, in Northern France, he possessed Évreux, Mortain, parts of Vexin, and a portion of Cotentin. Charles was a major player at a critical juncture in the Hundred Years' War between France and England, repeatedly switching sides in order to further his own agenda. He was accidentally burned alive in 1387.

Life

[edit]Early life

[edit]Charles was born in Évreux, the son of Philip III and Joan II of Navarre.[2] His father was first cousin to King Philip VI of France, while his mother, Joan, was the only daughter of Louis X of France. Charles was 'born of the fleur-de-lys on both sides', as he liked to point out, but he succeeded to a shrunken inheritance as far as his French lands were concerned. He was raised in France during childhood and up to the moment he was declared king at 17, so he probably had no command of the Romance language of Navarre at the moment of his coronation.[3]

In October 1349, Charles' mother died.[4] In order to take his coronation oath and be anointed, he visited his kingdom in summer 1350.[4] For the first time, the oath was taken in a language other than the customary Latin or Occitan, i.e. Navarro-Aragonese. Apart from short visits paid the first 12 years of his reign, Charles spent his time almost entirely in France; he regarded Navarre principally as a source of manpower with which to advance his designs on the throne of France.[5] He hoped for a long time for recognition of his claim to the crown of France (as the heir-general of Philip IV through his mother, and a Capetian through his father). However, he was unable to wrest the throne from his Valois cousins, who were senior to him by agnatic primogeniture.[5]

Murder of Charles de la Cerda and relations with John II (1351–1356)

[edit]Charles II served as Royal Lieutenant in Languedoc in 1351 and commanded the army which captured Port-Sainte-Marie on the Garonne in 1352. The same year he married Joan of Valois, the daughter of King John II of France.[6] He soon became jealous of the Constable of France, Charles de La Cerda, who was to be a beneficiary of the fiefdom of Angoulême. Charles of Navarre felt he was entitled to these territories as they had belonged to his mother, the Queen of Navarre, but they had been taken from her by the French kings for a paltry sum in compensation.[7]

After publicly quarrelling with Charles de la Cerda in Paris at Christmas 1353, Charles arranged the assassination of the Constable, which took place at the village of l'Aigle on 8 January 1354, with his brother Philip, Count of Longueville leading the murderers. Charles made no secret of his role in the murder, and within a few days was intriguing with the English for military support against his father-in-law King John II, whose favourite the Constable had been.[8] John was preparing to attack his son-in-law's territories, but Charles' overtures of alliance to King Edward III of England led John to instead make peace with Charles with the Treaty of Mantes, enacted on 22 February 1354, by which Charles enlarged his possessions and was outwardly reconciled with John. The English, who had been preparing to invade France for a joint campaign with Charles against the French, felt they had been double-crossed: not for the last time, Charles had used the threat of an English alliance to wrest concessions out of the French king.

Relations between Charles and John once more deteriorated; in late 1354, John invaded Charles's territories in Normandy, while Charles intrigued with the Duke of Lancaster, serving as emissary for Edward III, at fruitless peace negotiations between England and France held in the winter of 1354–55 at Avignon. Once again, Charles changed sides: the threat of a renewed English invasion forced John to make a new agreement of reconciliation with him, which was ultimately sealed by the Treaty of Valognes on 10 September 1355.

This agreement, too, did not last. Charles befriended and was thought to be trying to influence the Dauphin—the future Charles V—and was apparently involved in a botched coup d'état in December 1355, whose purpose appears to have been to replace John with the Dauphin.[9] John amended matters by making his son Duke of Normandy, but Charles of Navarre continued to advise the Dauphin how to govern that province.

There were also continued rumours of his plots against the king, and on 5 April 1356 John II and a group of supporters burst unannounced into the Dauphin's castle at Rouen, arrested Charles of Navarre and imprisoned him. Four of his principal supporters—two of whom had been among de la Cerda's assassins—were beheaded, and their bodies suspended from chains. Charles was taken to Paris, and once there he was moved from prison to prison for greater security.[10]

Versus the Dauphin (1356–1358)

[edit]After John was captured by the English following his defeat at the Battle of Poitiers, Charles remained in prison. However, many of his partisans were active in the Estates General, which endeavoured to govern and reform France in the power vacuum created by the imprisonment of the king, while much of the country degenerated into anarchy. They continually pressed the Dauphin to release him. Meanwhile his brother Philip of Navarre threw in his lot with the invading English army of the Duke of Lancaster, and made war on the Dauphin's forces throughout Normandy. Eventually, on 9 November 1357, Charles was sprung from his prison in the castle of Arleux by a band of 30 men from Amiens led by Jean de Picquigny.[11] Greeted as a hero when he entered Amiens, he was invited to Paris by the Estates General. He entered Paris with a large retinue, and was 'received like a newly-crowned monarch'.[12]

He addressed the populace on 30 November, listing his grievances against those who had imprisoned him. Étienne Marcel led a 'demand for justice for the King of Navarre' which the Dauphin was unable to resist. Charles demanded an indemnity for all damage done to his territories while he had been imprisoned, free pardon for all his crimes and those of his supporters, and honourable burial for his associates executed by John II at Rouen. He also demanded the Dauphin's own Duchy of Normandy and the County of Champagne, which would have made him the effective ruler of northern France.

The Dauphin was virtually powerless, but he and Charles were still in negotiations when news reached them that Edward and John were reaching a peace agreement. Knowing this could only be to his disadvantage, Charles had all the prisons in Paris opened to create anarchy, and left Paris to build up his strength in Normandy.[13] In his absence the Dauphin tried to assemble a military force of his own. Charles meanwhile gave his executed followers a solemn state funeral in Rouen Cathedral on 10 January 1358 and effectively declared civil war, leading a combined Anglo-Navarrese force against the Dauphin's garrisons.

Revolution in Paris and the Jacquerie (1358)

[edit]

Meanwhile Paris was in the throes of revolution. On 22 February the Dauphin's chief military officers, the marshals Jean de Conflans and Robert de Clermont were murdered before his eyes by a mob led by Etienne Marcel, who made the Dauphin a virtual prisoner and invited Charles of Navarre to return to the city, which he did on 26 February with a large armed retinue. The Dauphin was forced to agree to many of Charles's territorial demands and to promise to finance for him a standing army of 1,000 men for his personal use.[14] However illness prevented Charles from escorting the Dauphin to meetings demanded by the nobility at Senlis and Provins, and the Dauphin was thus able to escape his Parisian and Navarrese guardians and open a campaign from the east against Charles and against revolutionary Paris.

Etienne Marcel implored Charles to intercede with the Dauphin but he achieved nothing and the land around Paris began to be plundered both by Charles's forces and by the Dauphin's. In the last days of May the peasant rebellion of the Jacquerie erupted to the north of Paris as a spontaneous expression of hatred for the nobility that had brought France so low. Etienne Marcel publicly declared Parisian support for the Jacquerie. Unable to get help from the Dauphin, the knights of northern France appealed to Charles of Navarre to lead them against the peasants.

Although he was allied with the Parisians, Charles was no lover of the peasantry and felt Marcel had made a fatal mistake. He could not resist the chance to appear as a leader of the French aristocracy and led the suppression of the Jacquerie at the Battle of Mello, 10 June 1358 and the subsequent massacres of rebels. He then returned to Paris and made an open bid for power urging the populace to elect him as 'Captain of Paris'.[15]

This move lost Charles the support of many of the nobles who had supported him against the Jacquerie, and they began to abandon him for the Dauphin while he recruited soldiers—mainly English mercenaries—for the 'defence' of Paris, though his men, picketed outside the city, raided and plundered far and wide. Realizing the Dauphin's forces were much stronger than his, Charles opened negotiations with the Dauphin, who made him substantial offers of cash and land if he could induce the Parisians to surrender. They, however, distrusted this deal between princes and refused the terms outright; Charles agreed to fight on as their captain but demanded that his troops be billeted in the city.

Before long there were anti-English riots in the city and Charles, with Etienne Marcel, was forced by the mob to lead them against the marauding garrisons to the north and west of the city—against his own men. He led them (no doubt deliberately) into an English ambush in the woods near the bridge of Saint-Cloud and about 600 Parisians were killed.[16]

Capitulation (1359–60)

[edit]After this debacle Charles stayed outside Paris at the Abbey of St Denis and left the city to its fate while the revolution burned itself out, Etienne Marcel was killed, and the Dauphin regained control of Paris. Meanwhile he opened negotiations with the English King, proposing that Edward III and he should divide France between themselves: if Edward would invade France and help him defeat the Dauphin, he would recognize Edward as King of France and do homage to him for the territories of Normandy, Picardy, Champagne and Brie.[17] But the English king no longer trusted Charles and both he and the captive John II regarded him as an obstacle to peace. On 24 March 1359, Edward and John concluded a new treaty in London whereby John would be released back to France on payment of a huge ransom and would make over to Edward III large tracts of French territory—including all of Charles of Navarre's French lands. Unless Charles submitted and accept suitable (undefined) compensation elsewhere, the Kings of England and France would jointly make war on him.[18] However the Estates General refused to accept the treaty, urging the Dauphin to continue the war. At this Edward III lost patience and decided to invade France himself. Charles of Navarre's military position in Northern France had deteriorated under attacks from the Dauphin's forces throughout the spring, and with the news of Edward's impending invasion Charles decided he must reach an accommodation with the Dauphin. After protracted haggling the two leaders met near Pontoise on 19 August 1359; on the second day Charles of Navarre publicly renounced all his demands for territory and money, saying he wanted nothing more than what he had at the beginning of hostilities and 'wanted nothing more than to do his duty to his country'. It is unclear whether he was actuated by patriotism in the face of an imminent English invasion, or had decided to bide his time until a more favourable juncture to renew his campaign.[19] After the comparative failure of Edward's campaign in the winter of 1359–60—the Dauphin did not offer battle, instead pursuing a 'scorched earth' policy, with the populace seeking shelter inside walled towns while the English endured terrible weather—a final peace treaty was agreed between Edward and John at Brétigny, while John II concluded a separate peace with Charles of Navarre at Calais. Charles was forgiven his crimes against France and restored to all his rights and properties; 300 of his followers received a royal pardon. In return, he renewed his homage to the French crown and promised to help clear the French provinces of the marauding companies of Anglo-Navarrese mercenaries, many of which he had been responsible for unleashing in the first place.[20]

Burgundian inheritance and the loss of Normandy (1361–1365)

[edit]In 1361, after the death of his second cousin the young Duke Philip I of Burgundy, Charles claimed the Duchy of Burgundy by primogeniture. He was the grandson of Margaret, eldest daughter of Duke Robert II of Burgundy (d. 1306). However, the duchy was taken by King John II, who was son of Joan, second daughter of Duke Robert II, who claimed it in proximity of blood, and made provision that after his death it would pass to his favourite son Philip the Bold.

To have become Duke of Burgundy would have given Charles the position at the centre of French politics that he had always craved, and the abrupt dismissal of his claim provoked fresh bitterness. After the failure of an attempt to win Pope Innocent VI to his claim, Charles returned to his kingdom of Navarre in November 1361. He was soon plotting afresh to become a power in France. A planned rising of his supporters in Normandy in May 1362 was an abject failure, but in 1363 he evolved an ambitious plan to form two armies in 1364, one of which would go by sea to Normandy and the other, under his brother Louis, would join forces with the Gascons operating with the Great Company in Central France and invade Burgundy, thus threatening the French King from both sides of his realm. In January 1364 Charles met Edward, the Black Prince, at Agen in order to negotiate the passage of his troops through the English-held duchy of Aquitaine, to which the Prince agreed perhaps because of his friendship with Charles's new military adviser Jean III de Grailly, captal de Buch, who had been betrothed to Charles' sister and was to lead his army to Normandy.[21] In March 1364 the Captal marched towards Normandy to secure Charles's domains.

John II of France had returned to London to negotiate with Edward III, and the defence of France was once more in the hands of the Dauphin. There was already a royal army in Normandy besieging the town of Rolleboise, nominally commanded by the Count of Auxerre but actually generalled by Bertrand du Guesclin. Charles's designs were well known in advance and in early April 1364 this force seized many of Charles's remaining strongholds before the Captal de Buch could reach Normandy. When he arrived he started concentrating his forces around Évreux, which still held out for Charles. He then led his army against the royal forces to the east. On 16 May 1364 he was defeated by du Guesclin at the Battle of Cocherel. John II had died in England in April, and news of the victory of Cocherel reached the Dauphin on 18 May at Rheims, where on the following day he was crowned Charles V of France.[22] He immediately confirmed his brother Philip as Duke of Burgundy.

Undeterred by this resounding defeat, Charles of Navarre persisted in his grand design. In August 1364 his men began a fight back in Normandy while a small Navarrese army under Rodrigo de Uriz sailed from Bayonne to Cherbourg. Meanwhile Charles's brother Louis of Navarre led an army augmented by contingents pledged by the captains of the Great Company and the freebooter Seguin de Badefol through the Black Prince's territories and across France, evading the French royal forces sent to intercept him and arrived in Normandy on 23 September. Hearing of the collapse of the civil war in Brittany after the Battle of Auray on 29 September, Louis abandoned his design to invade Burgundy and instead set about reconquering the Cotentin for Charles. Meanwhile Séguin de Badefol and his fellow-captains captured the town of Anse on the Burgundian border, but only to use it as a centre for raiding and plundering far and wide. They did Charles of Navarre's cause no discernible good, and Pope Urban V excommunicated Séguin. Although Charles offered Bernard-Aiz V, Lord of Albret, huge sums to take over the command of his forces around Burgundy, he finally realized he could not prevail against the King of France and must come to an accommodation with him. In May 1365, in Pamplona, he agreed to a treaty by which there was to be a general amnesty for his supporters, the remains of Navarrese executed and displayed for treason were to be returned to their families, prisoners would be mutually released without ransom. Charles was allowed to keep his conquests of 1364, except for the citadel of Meulan, which was to be razed to the ground. In compensation Charles received Montpellier in Bas-Languedoc. His claim to Burgundy was to be referred to the arbitration of the Pope.[23] The Pope never in fact pronounced on the matter. It was an ignominious end to Charles's 15 years of struggle to create a major territory for himself and his line in France. Henceforth he resided mainly in his kingdom.

At the end of 1365 Séguin de Badefol arrived in Navarre to claim the considerable sums Charles had pledged to pay him for his services in Burgundy, even though he had achieved nothing of substance. Charles was not pleased to see him, received him in private and poisoned him with a crystallised pear.[24]

Charles and the Spanish Wars (1365–1368)

[edit]The cessation of war in France left vast numbers of French, English, Gascon and Navarrese soldiers and freebooters in search of mercenary employment, and many of these soon became involved in the wars of Castille and Aragon, both of which bordered Navarre. Charles typically tried to exploit the situation by making agreements with both sides that would enlarge his territory while leaving Navarre itself relatively untouched. Officially he was ally of Peter of Castile, but at the end of 1365 he concluded a secret agreement with Peter IV of Aragon to allow the marauding army led by Bertrand du Guesclin and Hugh Calveley to invade Castile through southern Navarre in order to depose Pedro I and supplant him with his half-brother Henry of Trastámara. He then reneged on his agreements to both sides and attempted to hold the Navarrese borders intact, but was unable to do so and instead paid the invaders a large sum to keep their plundering to a minimum.

After Henry of Trastámara successfully seized the throne of Castile, Pedro I fled to the court of the Black Prince in Aquitaine, who began to plot his restoration by sending an army across the Pyrenees. In July 1366 Charles himself came to Bordeaux to consult with Pedro I and the Prince and agreed to keep the mountain passes of Navarre open for the passage of the army, for which he would be rewarded with the Castilian provinces of Guipúzcoa and Álava as well as additional fortresses and a large cash payment. Then in December he met Henry of Trastámara on the Navarrese border and promised instead to hold the passes closed, in return for the border town of Logroño and more cash. Hearing of this the Black Prince ordered Hugh Calveley to invade Navarre from northern Castile and enforce the original agreement. Charles at once capitulated, claiming he had never been sincere in his dealings with Henry, and opened the passes to the Prince's army. Charles accompanied them on their journey but, not wanting to take part in the campaign personally, got Olivier de Mauny to stage an ambush in which Charles was 'captured' and held until the reconquest of Castile was over. The ruse was so transparent it made Charles a laughing-stock in Western Europe.[25]

Last French possessions lost and the humbling of Navarre (1369–79)

[edit]With the resumption of war between France and England in 1369 Charles saw fresh opportunities to increase his status in France. He left Navarre and met Duke John V of Brittany in Nantes, where they agreed to come to each other's aid if either was attacked by France. Basing himself in Cherbourg, the principal town in what remained of his territories in Northern Normandy, he then sent ambassadors to Charles V of France and Edward III of England. He offered to aid the French King if he would restore his former territories in Normandy, recognize his claim to Burgundy and bestow the promised lordship of Montpellier. To the English king he offered an alliance against France, whereby Edward III could use his territories in Normandy as a base to attack the French. As on previous occasions, Charles did not really want an English army on his lands; he wanted the threat of one to put pressure on Charles V.[26] But Charles V refused his demands outright. On the strength of Charles of Navarre's offers, Edward III despatched an expeditionary force to the Seine estuary under Sir Robert Knolles in July 1370. He invited Charles to come to England in person—which he did during that same month. Charles of Navarre entered into secret negotiations with Edward III at Clarendon Palace, but committed himself to very little.[27] Simultaneously he continued to negotiate with Charles V, who feared the King of Navarre would throw in his lot with Knolles's army now operating in Northern France. Though Edward III sealed a draft treaty with Navarre on 2 December 1370 it was a dead letter after the destruction of Knolles's army at the Battle of Pontvallain a few days later. During March 1371, seeing no option left, Charles of Navarre had a series of meetings with Charles V and did homage to him.

Having gained little or nothing from these activities, he returned to Navarre in early 1372. He was subsequently involved in at least two attempts to have Charles V poisoned and encouraged various plots by others against the French King.[28] He next entered into negotiations with John of Gaunt, who was aiming to make himself King of Castile by virtue of his marriage to Pedro I's daughter Constanza. But in 1373 Henry of Trastámara, now firmly installed as King of Castile and victorious in war against England's ally Portugal, forced Charles to agree to a marriage alliance, to surrender the disputed border fortresses he had held on to since the Castilian civil war, and to close his borders to any army of John of Gaunt.[29] Nevertheless in March 1374 Charles met John of Gaunt in Dax in Gascony and agreed to let him use Navarre as a base for invading Castile on condition he recapture the towns surrendered to Henry. Gaunt's sudden decision only a few days later to abandon his plans and return to England Charles took as a personal betrayal. In order to placate the Castilian King he now agreed for his eldest son, the future Charles III of Navarre, to marry Henry of Trastámara's daughter Leonora in May 1375.[30]

In 1377 he proposed to the English that he would return to Normandy and put the harbours and castles he still controlled there at their disposal for a joint attack on France; he also proposed that his daughter should be married to the new English king, the young Richard II.[31] But the threat of an attack by Castile forced Charles to remain in Navarre. Instead he sent off his eldest son to Normandy, with a number of officials, including his chamberlain Jacques de Rue, who were to prepare his castles to receive the English, as well as a servant whose mission was to insinuate himself into the royal kitchens in Paris and poison the King of France.[32] Meanwhile he urgently appealed for the English to send him reinforcements from Gascony to help him fight the Castilians. But in March 1378 all his plots finally unravelled. On their way to Normandy the Navarrese delegation were arrested at Nemours. The draft treaties and correspondence with the English found in their baggage, along with Jacques de Rue's confessions under interrogation, were all that Charles V needed to send an army into northern Normandy to capture all the King of Navarre's remaining domains there (April–June 1378). Only Cherbourg held out: Charles of Navarre begged the English to send him reinforcements there but instead they seized it for themselves and garrisoned it against the French. Charles's son submitted to the French King and became a protégé of the Duke of Burgundy, fighting in the French armies. Jacques de la Rue and other prominent Navarrese officials in France were executed.[33]

From June–July 1378 the armies of Castile, commanded by John of Trastámara, invaded Navarre and laid the country waste. Charles II retreated over the Pyrenees to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port and in October he made his way to Bordeaux to plead for military aid from Sir John Neville, the Lieutenant of Gascony. Neville despatched a small force to Navarre under the knight Sir Thomas Trivet, but the English achieved little over the winter and in February Henry of Trastámara announced his son would re-invade Navarre in the spring. Having no options or allies left Charles II asked for a truce, and by the Treaty of Briones on 31 March 1379 agreed to Henry's demands that he agree to be bound in perpetual military alliance with Castile and France against the English, and to surrender 20 fortresses of southern Navarre, including the city of Tudela, to Castilian garrisons.[34]

Charles of Navarre's remarkably slippery and devious political career was at an end. He retained his crown and his country but he was effectively a humiliated client of his enemies, he had lost his French territories and his Pyrenean realm was devastated and impoverished by war. Though he continued to scheme and even still to consider himself the rightful King of France, he was essentially neutralized and impotent for the years that remained until his gruesome death.

Marriage and children

[edit]He married Joan of France (1343–1373), daughter of King John II of France. He had the following children by Joan:

- Marie (1360, Puente la Reina – aft. 1400), married in Tudela on 20 January 1393 Alfonso d'Aragona, Duke of Gandia

- Charles III of Navarre (1361–1425)

- Bonne (1364 – aft. 1389)

- Pedro, Count of Mortain (c. 31 March 1366, Évreux – c. 29 July 1412, Bourges[35]), married in Alençon on 21 April 1411 Catherine of Alençon (1380–1462), daughter of Peter II of Alençon. He had a son out of wedlock named Pedro Perez de Peralta 1400–1451.

- Philip (b. 1368), d. young

- Joanna of Navarre (1370–1437), married firstly John IV, Duke of Brittany, married secondly Henry IV of England

- Blanche (1372–1385, Olite)

Death

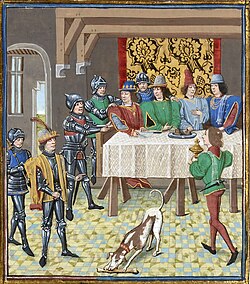

[edit]Charles died in Pamplona, aged 54. His horrific death became famous all over Europe, and was often cited by moralists, and sometimes illustrated in illuminated manuscript chronicles.[36] There are several versions of the story, varying in the details. This is Francis Blagdon's account from 1803:

Charles the Bad, having fallen into such a state of decay that he could not make use of his limbs, consulted his physician, who ordered him to be wrapped up from head to foot, in a linen cloth impregnated with brandy, so that he might be inclosed [sic] in it to the very neck as in a sack. It was night when this remedy was administered. One of the female attendants of the palace, charged to sew up the cloth that contained the patient, having come to the neck, the fixed point where she was to finish her seam, made a knot according to custom; but as there was still remaining an end of thread, instead of cutting it as usual with scissors, she had recourse to the candle, which immediately set fire to the whole cloth. Being terrified, she ran away, and abandoned the king, who was thus burnt alive in his own palace.[37]

John Cassell's moralistic version states:

He was now sixty years of age, and a mass of disease, from the viciousness of his habits. To maintain his warmth his physician ordered him to be swathed in linen steeped in spirits of wine, and his bed to be warmed by a pan of hot coals. He had enjoyed the benefit of this singular prescription some time in safety, but now, as he was perpetrating his barbarities on the representatives of his kingdom, "by the pleasure of God, or of the devil," says Froissart, "the fire caught to his sheets, and from that to his person, swathed as it was in matter highly inflammable." He was fearfully burnt, but lingered nearly a fortnight, in the most terrible agonies.[38]

Family tree

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Although the nickname (French le Mauvais, Spanish el Malo) has stuck, it was first used by Diego Ramírez de Ávalos de La Piscina in his manuscript chronicle Crónica de los muy excelentes Reyes de Navarra in 1534. It did not appear in print until 1571.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ Morby 1978, p. 5.

- ^ Henneman 1971, p. xvii.

- ^ González Olle 1987, p. 706.

- ^ a b Sumption 1999, p. 107.

- ^ a b sheldon, Natasha (8 June 2017). "King Charles II Died a Horrible, Unfortunate Death". Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ Sumption 1999, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Sumption 1999, p. 103.

- ^ Sumption 1999, p. 124–125.

- ^ Sumption 1999, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Sumption 1999, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Sumption 1999, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Sumption 1999, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Sumption 1999, p. 302.

- ^ Sumption 1999, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Sumption 1999, pp. 317–337.

- ^ Sumption 1999, pp. 338–344.

- ^ Sumption 1999, p. 348.

- ^ Sumption 1999, pp. 400–401.

- ^ Sumption 1999, pp. 418–421.

- ^ Sumption 1999, p. 453.

- ^ Sumption 1999, pp. 504–505.

- ^ Sumption 1999, p. 508–511.

- ^ Sumption 1999, pp. 520–523.

- ^ Sumption 1999, p. 525.

- ^ Sumption 1999, pp. 545, 548–549.

- ^ Sumption 2009, pp. 64–67.

- ^ Sumption 2009, pp. 72–74.

- ^ Sumption 2009, p. 312.

- ^ Sumption 2009, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Sumption 2009, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Sumption 2009, p. 313.

- ^ Sumption 2009, p. 314.

- ^ Sumption 2009, pp. 317–321.

- ^ Sumption 2009, pp. 333–339.

- ^ Sumption 2015, p. 317.

- ^ Barbara Tuchman (1978). A Distant Mirror. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780394400266.

- ^ Francis William Blagdon (1803). Paris as it was and as it is. C. and R. Baldwin. pp. 273–274.

- ^ John Cassell (1857). Illustrated History of England. Vol. 1. London: W. Kent & Co. p. 404.

Sources

[edit]- González Olle, Fernando (1987). "Reconocimiento del Romance Navarro bajo Carlos II (1350)". Príncipe de Viana. 1 (182). Gobierno de Navarra; Institución Príncipe de Viana. ISSN 0032-8472.

- Henneman, John Bell (1971). Royal Taxation in Fourteenth Century France. Princeton University Press.

- Morby, John E. (1978). "The Sobriquets of Medieval European Princes". Canadian Journal of History. 13 (1): 1–16. doi:10.3138/cjh.13.1.1.

- Sumption, Jonathan (1999). Trial by Fire: The Hundred Years War. Vol. II. Faber & Faber.

- Sumption, Jonathan (2009). Divided Houses: The Hundred Years War. Vol. III. Faber & Faber.

- Sumption, Jonathan (2015). Cursed Kings: Hundred Years War. Vol. IV. Faber & Faber.