Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Occitan language

View on Wikipedia

| Occitan | |

|---|---|

| occitan, lenga d'òc, provençal / provençau | |

| Pronunciation | [leŋɡɒ ˈðɔ(k)] ⓘ |

| Native to | France, Spain, Italy, Monaco |

| Region | Occitania |

| Ethnicity | Occitans |

Native speakers | (c. 200,000 cited 1990–2012)[1] Estimates range from 100,000 to 800,000 total speakers (2007–2012),[2][3] with 68,000 in Italy (2005 survey),[4] 4,000 in Spain (Val d'Aran)[5] |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

Standard forms | |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin alphabet (Occitan alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Spain |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Conselh de la Lenga Occitana;[7] Congrès Permanent de la Lenga Occitana;[8] Institut d'Estudis Aranesi[9] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | oc |

| ISO 639-2 | oci |

| ISO 639-3 | oci – inclusive codeIndividual code: sdt – Judeo-Occitan |

| Glottolog | occi1239 |

| Linguasphere | & 51-AAA-f 51-AAA-g & 51-AAA-f |

Geographic range of the Occitan language around 1900 | |

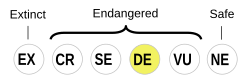

Provençal, Auvergnat, Limousin, Gardiol, and Languedocien Occitan are classified as Severely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger.[10] Gascon and Vivaro-Alpine Occitan are classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger.[11] | |

Occitan (English: /ˈɒksɪtən, -tæn, -tɑːn/;[12][13] Occitan pronunciation: [utsiˈta, uksiˈta]),[a] also known by its native speakers as lenga d'òc (Occitan: [ˈleŋɡɒ ˈðɔ(k)] ⓘ; French: langue d'oc), sometimes also referred to as Provençal, is a Romance language spoken in Southern France, Monaco, Italy's Occitan Valleys, as well as Spain's Val d'Aran in Catalonia; collectively, these regions are sometimes referred to as Occitania. It is also spoken in Calabria (Southern Italy) in a linguistic enclave of Cosenza area (mostly Guardia Piemontese) named Gardiol, which is also considered a separate Occitanic language.[14] Some include Catalan as a dialect of Occitan, as the linguistic distance between this language and some Occitan dialects (such as the Gascon language) is similar to the distance between different Occitan dialects. Catalan was considered a dialect of Occitan until the end of the 19th century[15] and still today remains its closest relative.[16] Occitan has a particularly rich lexicon. Lo Panoccinari, considered the most comprehensive dictionary ever published in this language, records over 250,000 unique words[17] (more than 310,000 including dialectal variations).

Occitan is an official language of Catalonia, Spain, where a subdialect of Gascon known as Aranese is spoken (in the Val d'Aran).[18] Since September 2010, the Parliament of Catalonia has considered Aranese Occitan to be the officially preferred language for use in the Val d'Aran.

Across history, the terms Limousin (Lemosin), Languedocien (Lengadocian), Gascon, in addition to Provençal (Provençal, Provençau or Prouvençau) later have been used as synonyms for the whole of Occitan; nowadays, the term "Provençal" is understood mainly as the Occitan dialect spoken in Provence, in southeast France.[19]

Unlike other Romance languages such as French or Spanish, Occitan does not have a single written standard form, nor does it have official status in France, home to most of its speakers. Instead, there are competing norms for writing Occitan, some of which attempt to be pan-dialectal, whereas others are based on a particular dialect. These efforts are hindered by the rapidly declining use of Occitan as a spoken language in much of southern France, as well as by the significant differences in phonology and vocabulary among different Occitan dialects.

According to the UNESCO Red Book of Endangered Languages,[20] four of the six major dialects of Occitan (Provençal, Auvergnat, Limousin and Languedocien) are considered severely endangered, whereas the remaining two (Gascon and Vivaro-Alpine) are considered definitely endangered.

Name

[edit]History of the modern term

[edit]The name Occitan comes from the term lenga d'òc ("language of òc"), òc being the Occitan word for yes. While the term would have been in use orally for some time after the decline of Latin, as far as historical records show, the Italian medieval poet Dante was the first to have recorded the term lingua d'oc in writing. In his De vulgari eloquentia, he wrote in Latin, "nam alii oc, alii si, alii vero dicunt oil" ("for some say òc, others sì, yet others say oïl"), thereby highlighting three major Romance literary languages that were well known in Italy, based on each language's word for "yes", the òc language (Occitan), the oïl language (French), and the sì language (Italian).

The word òc came from Vulgar Latin hoc ("this"), while oïl originated from Latin hoc illud ("this [is] it"). Old Catalan and now the Catalan of Northern Catalonia also have hoc (òc). Other Romance languages derive their word for "yes" from the Latin sic, "thus [it is], [it was done], etc.", such as Spanish sí, Eastern Lombard sé, Italian sì, or Portuguese sim. In modern Catalan, as in modern Spanish, sí is usually used as a response, although the language retains the word oi, akin to òc, which is sometimes used at the end of yes–no questions and also in higher register as a positive response.[21] French uses si to answer "yes" in response to questions that are asked in the negative sense: for example, "Vous n'avez pas de frères?" "Si, j'en ai sept." ("You don't have any brothers, do you ?" "Yes I do, I have seven.").

The name "Occitan" was attested around 1300 as occitanus, a crossing of oc and aquitanus (Aquitanian).[22]

Other names for Occitan

[edit]For many centuries, the Occitan dialects (together with Catalan)[23] were referred to as Limousin or Provençal, after the names of two regions lying within the modern Occitan-speaking area. After Frédéric Mistral's Félibrige movement in the 19th century, Provençal achieved the greatest literary recognition and so became the most popular term for Occitan.

According to Joseph Anglade, a philologist and specialist of medieval literature who helped impose the then archaic term Occitan as the standard name,[24] the word Lemosin was first used to designate the language at the beginning of the 13th century by Catalan troubadour Raimon Vidal de Besalú(n) in his Razós de trobar:

La parladura Francesca val mais et [es] plus avinenz a far romanz e pasturellas; mas cella de Lemozin val mais per far vers et cansons et serventés; et per totas las terras de nostre lengage son de major autoritat li cantar de la lenga Lemosina que de negun'autra parladura, per qu'ieu vos en parlarai primeramen.[25]

The French language is worthier and better suited for romances and pastourelles; but [the language] from Limousin is of greater value for writing poems and cançons and sirventés; and across the whole of the lands where our tongue is spoken, the literature in the Limousin language has more authority than any other dialect, wherefore I shall use this name in priority.

The term Provençal, though implying a reference to the region of Provence, historically was used for Occitan as a whole, for "in the eleventh, the twelfth, and sometimes also the thirteenth centuries, one would understand under the name of Provence the whole territory of the old Provincia romana Gallia Narbonensis and even Aquitaine".[26] The term first came into fashion in Italy.[27]

Currently, linguists use the terms Provençal and Limousin strictly to refer to specific varieties within Occitan, using Occitan for the language as a whole. Many non-specialists, however, continue to refer to the language as Provençal.

History

[edit]One of the oldest written fragments of the language found dates back to 960, shown here in italics mixed with non-italicized Latin:

De ista hora in antea non decebrà Ermengaus filius Eldiarda Froterio episcopo filio Girberga ne Raimundo filio Bernardo vicecomite de castello de Cornone ... no·l li tolrà ni no·l li devedarà ni no l'en decebrà ... nec societatem non aurà, si per castellum recuperare non o fa, et si recuperare potuerit in potestate Froterio et Raimundo lo tornarà, per ipsas horas quæ Froterius et Raimundus l'en comonrà.[28]

Carolingian litanies (c. 780), though the leader sang in Latin, were answered to in Old Occitan by the people (Ora pro nos; Tu lo juva).[29]

Other famous pieces include the Boecis, a 258-line-long poem written entirely in the Limousin dialect of Occitan between the year 1000 and 1030 and inspired by Boethius's The Consolation of Philosophy; the Waldensian La nobla leyczon (dated 1100),[30] Cançó de Santa Fe (c. 1054–1076), the Romance of Flamenca (13th century), the Song of the Albigensian Crusade (1213–1219?), Daurel e Betó (12th or 13th century), Las, qu'i non-sun sparvir, astur (11th century) and Tomida femina (9th or 10th century).

Occitan was the vehicle for the influential poetry of the medieval troubadours (trobadors) and trobairitz: At that time, the language was understood and celebrated throughout most of educated Europe.[31] It was the maternal language of the English queen Eleanor of Aquitaine and kings Richard I (who wrote troubadour poetry) and John.

With the gradual imposition of French royal power over its territory, Occitan declined in status from the 14th century on. The Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts (1539) decreed that the langue d'oïl (French – though at the time referring to the Francien language and not the larger collection of dialects grouped under the name langues d'oïl) should be used for all French administration. Occitan's greatest decline occurred during the French Revolution, in which diversity of language was considered a threat.

In 1903, the four Gospels ("Lis Evangèli", i.e. Matthew, Mark, Luke and John) were translated into Provençal as spoken in Cannes and Grasse. The translation was given the official Roman Catholic Imprimatur by vicar general A. Estellon.[citation needed]

The literary renaissance of the late 19th century (in which the 1904 Nobel Prize in Literature winner, Frédéric Mistral, among others, was involved) was attenuated by World War I, when (in addition to the disruption caused by any major war) many Occitan speakers spent extended periods of time alongside French-speaking comrades.

Origins

[edit]Because the geographical territory in which Occitan is spoken is surrounded by regions in which other Romance languages are used, external influences may have influenced its origin and development. Many factors favored its development as its own language.

- Mountains and seas: The range of Occitan is naturally bounded by the Mediterranean, Atlantic, Massif Central, Alps, and Pyrenees, respectively.

- Buffer zones: arid land, marshes, and areas otherwise impractical for farming and resistant of colonization provide further separation (territory between Loire and Garonne, the Aragon desert plateau).

- Constant populations: Some Occitan-speaking peoples are descended from people living in the region since prehistoric times.[32]

- Deeper Roman influence: The Romans had established an earlier presence in Southern France in 121 BC beginning with Gallia Narbonensis, where the seeds of the Occitan language were first sown. According to Müller, "France's linguistic separation began with Roman influence"[33]

- A separate lexicon: Although Occitan is midway between the Gallo-Romance and Iberian Romance languages, it has "around 550 words inherited from Latin that no longer exist in the langues d'oïl or in Franco-Provençal"[33]

- Lack of Germanic influence: "The Frankish lexicon and its phonetic influence often end above the oc/oïl line"[33]

Occitan in the Iberian Peninsula

[edit]Catalan in Spain's northern and central Mediterranean coastal regions and the Balearic Islands is closely related to Occitan, sharing many linguistic features and a common origin (see Occitano-Romance languages). The language was one of the first to gain prestige as a medium for literature among Romance languages in the Middle Ages. Indeed, in the 12th and 13th centuries, Catalan troubadours such as Guerau de Cabrera, Guilhem de Bergadan, Guilhem de Cabestany, Huguet de Mataplana, Raimon Vidal de Besalú, Cerverí de Girona, Formit de Perpinhan, and Jofre de Foixà wrote in Occitan.

At the end of the 11th century, the Franks, as they were called at the time, started to penetrate the Iberian Peninsula through the Ways of St. James via Somport and Roncesvalles, settling in various locations in the Kingdoms of Navarre and Aragon enticed by the privileges granted them by the Navarrese kings. They settled in large groups, forming ethnic boroughs where Occitan was used for everyday life, in Pamplona, Sangüesa, and Estella-Lizarra, among others.[34] These boroughs in Navarre may have been close-knit communities that tended not to assimilate with the predominantly Basque-speaking general population. Their language became the status language chosen by the Navarrese kings, nobility, and upper classes for official and trade purposes in the period stretching from the early 13th century to the late 14th century.[35]

Written administrative records were in a koiné based on the Languedocien dialect from Toulouse with fairly archaic linguistic features, evidence survives of a written account in Occitan from Pamplona centered on the burning of borough San Nicolas from 1258, while the History of the War of Navarre by Guilhem Anelier (1276), albeit written in Pamplona, shows a linguistic variant from Toulouse.[36]

Things turned out slightly otherwise in Aragon, where the sociolinguistic situation was different, with a clearer Basque-Romance bilingual situation (cf. Basques from the Val d'Aran cited c. 1000), but a receding Basque language (Basque banned in the marketplace of Huesca, 1349).[37][38] While the language was chosen as a medium of prestige in records and official statements along with Latin in the early 13th century, Occitan faced competition from the rising local Romance vernacular, the Navarro-Aragonese, both orally and in writing, especially after Aragon's territorial conquests south to Zaragoza, Huesca and Tudela between 1118 and 1134. It resulted that a second Occitan immigration of this period was assimilated by the similar Navarro-Aragonese language, which at the same time was fostered and chosen by the kings of Aragon. In the 14th century, Occitan across the whole southern Pyrenean area fell into decay and became largely absorbed into Navarro-Aragonese first and Castilian later in the 15th century, after their exclusive boroughs broke up (1423, Pamplona's boroughs unified).[39]

Gascon-speaking communities were called to move in for trading purposes by Navarrese kings in the early 12th century to the coastal fringe extending from San Sebastian to the river Bidasoa, where they settled down. The language variant they used was different from the ones in Navarre, i.e. a Béarnese dialect of Gascon.[40] Gascon remained in use in this area far longer than in Navarre and Aragon, until the 19th century, thanks mainly to the fact that Donostia and Pasaia maintained close ties with Bayonne.

Geographic distribution

[edit]Number of speakers

[edit]The area where Occitan was historically dominant has approximately 16 million inhabitants. Recent research has shown it may be spoken as a first language by approximately 789,000 people[2][3] in France, Italy, Spain and Monaco. In Monaco, Occitan coexists with Monégasque Ligurian, which is the other native language.[41][42] Up to seven million people in France understand the language,[43][44][45] whereas twelve to fourteen million fully spoke it in 1921.[46] In 1860, Occitan speakers represented more than 39%[47] of the whole French population (52% for francophones proper); they were still 26% to 36% in the 1920s,[48] but less than 7% in 1993.

Usage in France

[edit]

Though it was still an everyday language for most of the rural population of southern France well into the 20th century, the language is now declining in every region where it was spoken.

A 2020 study[49] conducted by the Office Public de la Langue Occitane on the territories of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine and Occitanie regions estimated around 540,000 speakers in these two regions. It is worth noting that the survey was conducted in the Occitan language for respondents who declared they were proficient in it. However, the regions including Auvergne and Provence were effectively excluded from this census, as the Office in question does not currently have a partnership with these territories.

According to the 1999 census, there were 610,000 native speakers (almost all of whom were also native French speakers) and perhaps another million people with some exposure to the language. Following the pattern of language shift, most of this remainder is to be found among the eldest populations. Occitan activists (called Occitanists) have attempted, in particular with the advent of Occitan-language preschools (the Calandretas), to reintroduce the language to the young.[50]

Nonetheless, the number of proficient speakers of Occitan is thought to be dropping precipitously. A tourist in the cities in southern France is unlikely to hear a single Occitan word spoken on the street (or, for that matter, in a home), and is likely to only find the occasional vestige, such as street signs (and, of those, most will have French equivalents more prominently displayed), to remind them of the traditional language of the area.[51]

Occitan speakers, as a result of generations of systematic suppression and humiliation (see Vergonha), seldom use the language in the presence of strangers, whether they are from abroad or from outside Occitania (in this case, often merely and abusively referred to as Parisiens or Nordistes, which means northerners). Occitan is still spoken by many elderly people in rural areas, but they generally switch to French when dealing with outsiders.[52]

Occitan's decline is somewhat less pronounced in Béarn because of the province's history (a late addition to the Kingdom of France), though even there the language is little spoken outside the homes of the rural elderly. The village of Artix is notable for having elected to post street signs in the local language.[53]

Usage outside France

[edit]

- In the Val d'Aran, in the northwest corner of Catalonia, Spain, Aranese (a variety of Gascon) is spoken. It is an official language of Catalonia together with Catalan and Spanish.

- In Italy, Occitan is also spoken in the Occitan Valleys (Alps) in Piedmont. Gardiol also has existed at Guardia Piemontese (Calabria) since the 14th century. Italy adopted in 1999 a Linguistic Minorities Protection Law, or "Law 482", which includes Occitan; however, Italian is the dominant language. The Piedmontese language is extremely close to Occitan.

- In Monaco, some Occitan speakers coexist with remaining native speakers of Monégasque (Ligurian). French is the dominant language.

- Scattered Occitan-speaking communities have existed in different countries:

- There were Occitan-speaking colonies in Württemberg (Germany) since the 18th century, as a consequence of the Camisard war. The last Occitan speakers were heard in the 1930s.

- In the Spanish Basque country, Gascon was spoken in San Sebastián, perhaps as late as the early 20th century.[54]

- In the Americas, Occitan speakers exist:

- in the United States, in Valdese, North Carolina[55][56]

- in Canada, in Quebec where there are Occitan associations such as Association Occitane du Québec and Association des Occitans.[57]

- Pigüé, Argentina – Community settled by 165 Occitans from the Rodez-Aveyron area of Cantal in the late 19th century.

- Guanajuato, Mexico – A sparse number of Occitan settlers are known to have settled in that state in the 19th century.[58]

Traditionally Occitan-speaking areas

[edit]- Aquitaine – excluding the Basque-speaking part of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques in the western part of the department and a small part of Gironde where the langue d'oïl Saintongeais dialect is spoken.

- Midi-Pyrénées – including one of France's largest cities, Toulouse. There are a few street signs in Toulouse in Occitan, and since late 2009 the Toulouse Metro announcements are bilingual French-Occitan,[59] but otherwise the language is almost never heard spoken on the street.

- Languedoc-Roussillon (from "Lenga d'òc") – including the areas around the medieval city of Carcassonne, excluding the large part of the Pyrénées-Orientales where Catalan is spoken (Fenolheda is the only Occitan-speaking area of the Pyrénées-Orientales).

- Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur – except for the Roya and Bévéra valleys, where there is a transitional dialect between Ligurian and Occitan, (Roiasc, including the Brigasc dialect of Ligurian). In the department of Alpes-Maritimes there were once isolated towns that spoke Ligurian called Figún,[60] but those varieties are now extinct. The Mentonasc dialect of Ligurian, spoken in Menton, is a Ligurian transition dialect with a strong Occitan influence. French is the dominant language of the Alpes-Maritimes, Dauphiné and French Riviera areas.

- In Monaco, Occitan, imported by immigrants coexisted in the 19th and 20th centuries with the Monégasque dialect of Ligurian. French is the dominant language.

- Poitou-Charentes – Use of Occitan has declined here in the few parts it used to be spoken, replaced by French. Only Charente Limousine, the eastern part of the region, has resisted. The natural and historical languages of most of the region are the langues d'oïl Poitevin and Saintongeais.

- Limousin – A rural region (about 710,000 inhabitants) where Limousin is still spoken among the oldest residents. French is the dominant language.

- Auvergne – The language's use has declined in some urban areas. French is the dominant language. The department of Allier is divided between a southern, Occitan-speaking area and a northern, French-speaking area.

- Centre-Val de Loire – Some villages in the extreme South speak Occitan.

- Rhône-Alpes – While the south of the region is clearly Occitan-speaking, the central and northern Lyonnais, Forez and Dauphiné parts belong to the Franco-Provençal language area. French is the dominant language.

- Occitan Valleys (Piedmont) – Italian region where Occitan is spoken only in the southern and central Alpine valleys.

- Val d'Aran – part of Catalonia that speaks a mountain dialect of Gascon.

Pronunciation

[edit]The following section describes the pronunciation of the Languedocian dialect which is central geographically and the most conservative among Occitan dialects.[61] For that reason it serves as a basis for standardization of Occitan.[62]

Vowels

[edit]| Vowel[63] | Pronunciation |

|---|---|

| a (beginning or in a word); à | [a] |

| a (end of a word); á; ò | [o̞~ɔ, ɛ, e] |

| e, é | [e] |

| è | [ɛ] |

| o, ó | [u~w] |

| i, í | [i] |

| u, ú | [y~ɥ, w] |

Consonants

[edit]| Consonant[63] | Pronunciation | Consonant | Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| b, v ([v] in Northern and Eastern Occitan), w | [b~β] | p | [p] |

| c before a, o, u; qu before e and i | [k] | r-, rr | [r] |

| c before e and i; ç, s-, -s, sc, ss, -z | [s] | r inside words; rn, rm | [ɾ] |

| cc; ts | [s, ts, ks, kʃ] | -r | silent |

| d | [d~ð] | t | [t] |

| f | [f] | x | [(t)s] |

| g before a, o, u; gu | [g~ɣ] | z; s between vowels | [z] |

| g before e, i; j | [dʒ] | lh | [ʎ] |

| -g | [k, tʃ] | nh | [ɲ] |

| l; -lh | [l] | tz | [ts] |

| m; n and m before p, b and m | [m] | gn | [nː] |

| n, nd, nt; -m | [n] | tg; tj; ch | [tʃ] |

| n before c/qu and g/gu | [ŋ] | n and m before f | [ɱ] |

| qu before a and o | [kw] | ll; tl | [lː] |

Stress

[edit]Words ending with a vowel or s, as well as verb forms ending with n, have stress on the penultimate syllable. Words ending with a diphthong or a consonant (except s but including n) have stress on the last syllable. Exceptions have marked stress.[63]

Examples are:

La mecanica; destriar; cuélher; cantan; penós; gaton.

Grammar

[edit]The following section describes the grammar of the Languedocian dialect which is central geographically and most conservative among Occitan dialects.[61] For that reason it serves as a basis for standardization of Occitan.[62]

Pronouns

[edit]Personal pronouns are shown in the following table.[64]

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st per. | Ieu | Nosautres / nosautras / nos |

| 2nd per. | Tu | Vosautres / vosautras / vos |

| 3rd per. | El (=he)/ela (= she) | Eles (masculine), elas (feminine) |

Possessives

[edit]Possessives are shown in the following table.[64]

| Possessed thing is singular... | Possessed thing is plural... | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Possessor | and masculine | and feminine | and masculine | and feminine |

| I | Mon | Ma | Mos | Mas |

| You (sin.) | Ton | Ta | Tos | Tas |

| He/ she/ it | Son | Sa | Sos | Sas |

| We | Nòstre | Nòstra | Nòstres | Nòstras |

| You (pl.) | Vòstre | Vòstra | Vòstres | Vòstras |

| They | Lor | Lors | ||

Demonstratives

[edit]Demonstratives (this, that, these, those) are shown in the following table.[64]

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Aiceste/ Aqueste/ Aquel | Aicestes/ Aquestes/ Aqueles |

| Feminine | Aicesta/ Aquesta/ Aquela | Aicestas/ Aquestas/ Aquelas |

| Neuter | Aquò | Aquò |

Nouns

[edit]There are 2 genders: masculine, and feminine. Feminine nouns are usually created by adding termination -a.[64] Plural is created by adding -s to nouns.[64]

Articles

[edit]There are two indefinite articles in singular (a/an): masculine un and feminine una and one in plural: de.[64] de before vowels is shortend to d'.[64] It's summarized in the following table.

| Indefinite articles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |

| Masculine | un | de, d' |

| Feminine | una | de, d' |

Definite articles (the) are shown in the following table.[64]

| Definite articles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |

| Masculine | lo, l' | los |

| Feminine | la, l' | las |

l' is used before a vowel.[64]

Prepositions a, de, per and sus followed by articles lo and los are merged with them according to the following table.[64]

| lo | los | |

|---|---|---|

| a | al | als |

| de | del | dels |

| per | pel | pels |

| sus | sul | suls |

For instance a+los = als.

Verbs

[edit]Verbs inflect for person, number, tense and mood. There are 3 conjugations: -ar, -ir and -re.[65] Verbs ending with -ir have two subconjugations: with and without a suffix.[65]

Pattern of inflection of regular verbs belonging to the first conjugation is presented in the following table.[65]

Parlar (= to speak), parlat (= spoken), parlant (= speaking).

| Present | Imperfect | Preterit | Subjunctive Present | Subjunctive Past | Future | Conditional | Imperative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ieu | Parli | Parlavi | Parlèri | Parle | Parlèsse | Parlarai | Parlariái | |

| Tu | Parlas | Parlavas | Parlères | Parles | Parlèsses | Parlaràs | Parlariás | Parla |

| El/ela | Parla | Parlava | Parlèt | Parle | Parlèsse | Parlarà | Parlariá | |

| Nos | Parlam | Parlàvem | Parlèrem | Parlem | Parlèssem | Parlarem | Parlariam | Parlem |

| Vos | Parlatz | Parlàvetz | Parlèretz | Parletz | Parlèssetz | Parlaretz | Parlariatz | Parlatz |

| Eles/elas | Parlan | Parlavan | Parlèron | Parlen | Parlèsson | Parlaràn | Parlarián |

Conjugation -ir with the suffix is shown below.[65]

Dormir (= to sleep), dormit (= slept), dormint (= sleeping).

| Present | Imperfect | Preterite | Subjunctive present | Subjunctive past | Future | Conditional | Imperative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ieu | Dormissi | Dormissiái | Dormiguèri | Dormisca | Dormiguèsse | Dormirai | Dormiriái | |

| Tu | Dormisses | Dormissiás | Dormiguères | Dormiscas | Dormiguèsses | Dormiràs | Dormiriás | Dormís |

| El/ela | Dormís | Dormissiá | Dormiguèt | Dormisca | Dormiguèsse | Dormirà | Dormiriá | |

| Nos | Dormissèm | Dormissiam | Dormiguèrem | Dormiscam | Dormiguèssem | Dormirem | Dormiriam | Dormiscam |

| Vos | Dormissètz | Dormissiatz | Dormiguèretz | Dormiscatz | Dormiguèssetz | Dormiretz | Dormiriatz | Dormissètz |

| Eles/elas | Dormisson | Dormissián | Dormiguèron | Dormiscan | Dormiguèsson | Dormiràn | Dormirián |

Second conjugation without the suffix is shown below.[65]

Sentir (= to feel), sentit (= felt), sentent (= feeling).

| Present | Imperfect | Preterit | Subjunctive present | Subjunctive past | Future | Conditionnal | Imperative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ieu | Senti | Sentiái | Sentiguèri | Senta | Sentiguèsse | Sentirai | Sentiriái | |

| Tu | Sentes | Sentiás | Sentiguères | Sentas | Sentiguèsses | Sentiràs | Sentiriás | Sent |

| El/ ela | Sent | Sentiá | Sentiguèt | Senta | Sentiguèsse | Sentirà | Sentiriá | |

| Nos | Sentèm | Sentiam | Sentiguèrem | Sentam | Sentiguèssem | Sentirem | Sentiriam | Sentiam |

| Vos | Sentètz | Sentiatz | Sentiguèretz | Sentatz | Sentiguèssetz | Sentiretz | Sentiriatz | Sentètz |

| Eles/ elas | Senton | Sentián | Sentiguèron | Sentan | Sentiguèsson | Sentiràn | Sentirián |

The third conjugation is shown below.[65]

Batre (= to beat), batut (= beaten), beatent (= beating)

| Present | Imperfect | Preterit | Subjunctive present | Subjunctive past | Future | Conditionnal | Imperative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ieu | Bati | Batiái | Batèri | Bata | Batèsse | Batrai | Batriái | |

| Tu | Bates | Batiás | Batères | Batas | Batèsses | Batràs | Batriás | Bat |

| El/ela | Bat | Batiá | Batèt | Bata | Batèsse | Batrà | Batriá | |

| Nos | Batèm | Batiam | Batèrem | Batam | Batèssem | Batrem | Batriam | Batiam |

| Vos | Batètz | Batiatz | Batèretz | Batatz | Batèssetz | Batretz | Batriatz | Batètz |

| Eles/elas | Baton | Batián | Batèron | Batan | Batèsson | Batràn | Batrián |

Irregular verbs

[edit]Two very important irregular verbs are èsser/èstre (= to be) and aver (= to have).

Conjugation of èsser/èstre is shown below.[65]

estat (= been), essent (= being)

| Present | Imperfect | Preterit | Subjunctive present | Subjunctive past | Future | Conditionnal | Imperative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ieu | Soi | Èri | Foguèri | Siá | Foguèsse | Serai | Seriái | |

| Tu | Ès/Sès | Èras | Foguères | Siás | Foguèsses | Seràs | Seriás | Siá |

| El/ela | Es | Èra | Foguèt | Siá | Foguèsse | Serà | Seriá | |

| Nos | Sèm | Èrem | Foguèrem | Siam | Foguèssem | Serem | Seriam | Siam |

| Vos | Sètz | Èretz | Foguèretz | Siatz | Foguèssetz | Seretz | Seriatz | Siatz |

| Eles/elas | Son | Èran | Foguèron | Sián | Foguèsson | Seràn | Serián |

Conjugation of aver is shown below.[65]

agut (= had), avent (= having)

| Present | Imperfect | Preterit | Subjunctive present | Subjunctive past | Future | Conditionnal | Imperative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ieu | Ai | Aviái | Aguèri | Aja | Aguèsse | Aurai | Auriái | |

| Tu | As | Aviás | Aguères | Ajas | Aguèsses | Auràs | Auriás | Aja |

| El/ela | A | Aviá | Aguèt | Aja | Aguèsse | Aura | Auriá | |

| Nos | Avem | Aviam | Aguèrem | Ajam | Aguèssem | Aurem | Auriam | Ajam |

| Vos | Avètz | Aviatz | Aguèretz | Ajatz | Aguèssetz | Auretz | Auriatz | Ajatz |

| Eles/elas | An | Avián | Aguèron | Ajan | Aguèsson | Auràn | Aurián |

Reflexive verbs

[edit]Reflexive verbs are verbs which require reflexive pronoun se. Pronoun se inflects for person and number. An example is se levar (= to get up). It's inflacted according to the following table.[65]

| Present | Imperative | |

|---|---|---|

| Ieu | Me lèvi | |

| Tu | Te lèvas | lèva-te |

| El/elas | Se lèva | |

| Nos | Nos levam | levem-nos |

| Vos | Vos levatz | levatz-vos |

| Eles/elas | Se lèvan | tenon |

Negation

[edit]Negation is done by adding pas after a verb.[66] For example:

- Parli pas (= I don't speak).

- An pas parlat (= They haven't spoken).

- Vesi pas res (= I don't see anything).

- Lo tròbi pas enluòc (= I don't find him anywhere).

- Sortís pas jamai (= He never goes out).

- Degun es pas vengut (= Nobody came).

Dialects

[edit]

Occitan is fundamentally defined by its dialects, rather than being a unitary language, as it lacks an official written standard. Like other languages that fundamentally exist at a spoken, rather than written, level (e.g. the Rhaeto-Romance languages, Franco-Provençal, Astur-Leonese, and Aragonese), every settlement technically has its own dialect, with the whole of Occitania forming a classic dialect continuum that changes gradually along any path from one side to the other. Nonetheless, specialists commonly divide Occitan into six main dialects:

- Gascon: includes the Béarnese and Aranese (spoken in Spain).

- Languedocien (lengadocian)

- Limousin (lemosin)

- Auvergnat (auvernhat)

- Provençal (provençau or prouvençau), including the Niçard subdialect.

- Vivaro-Alpine (vivaroaupenc), also known as "Alpine" or "Alpine Provençal", and sometimes considered a subdialect of Provençal

The northern and easternmost dialects have more morphological and phonetic features in common with the Gallo-Italic and Oïl languages (e.g. nasal vowels; loss of final consonants; initial cha/ja- instead of ca/ga-; uvular ⟨r⟩; the front-rounded sound /ø/ instead of a diphthong, /w/ instead of /l/ before a consonant), whereas the southernmost dialects have more features in common with the Ibero-Romance languages (e.g. betacism; voiced fricatives between vowels in place of voiced stops; -ch- in place of -it-), and Gascon has a number of unusual features not seen in other dialects (e.g. /h/ in place of /f/; loss of /n/ between vowels; intervocalic -r- and final -t/ch in place of medieval -ll-).

There are also significant lexical differences, where some dialects have words cognate with French, and others have Catalan and Spanish cognates. Nonetheless, there is a significant amount of mutual intelligibility and some of the words with two cognates can be used in the same dialect as synonymous (totjorn/sempre in provençal or maison/ostau in gascon for instance).

There is also no particular geographical distribution of the cognates, with some shared by distant dialects and other not shared with bordering foreign languages (for instance maison in both Gascon and Niçard, cognate of French but not of Spanish or Italian, although these dialects are geographically closer to these languages).

| English | Cognate of French | Cognate of Catalan and Spanish | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occitan | French | Occitan | Catalan | Spanish | |

| house | maison | maison | casa | casa | casa |

| head | testa | tête | cap | cap | cabeza |

| to buy | achaptar | acheter | crompar | comprar | comprar |

| to hear | entendre | entendre | ausir / audir | oir | oír |

| to be quiet | se taire | se taire | calar | callar | callar |

| to fall | tombar | tomber | caire | caure | caer |

| more | pus | plus | mai | més | más |

| always | totjorn | toujours | sempre | sempre | siempre |

| broom | balaja | balai | escoba | escombra | escoba |

Gascon is the most divergent, and descriptions of the main features of Occitan often consider Gascon separately. Max Wheeler notes that "probably only its copresence within the French cultural sphere has kept [Gascon] from being regarded as a separate language", and compares it to Franco-Provençal, which is considered a separate language from Occitan but is "probably not more divergent from Occitan overall than Gascon is".[67]

There is no general agreement about larger groupings of these dialects.

Max Wheeler divides the dialects into two groups:[67]

- Southwestern (Gascon and Languedocien), more conservative

- Northeastern (Limousin, Auvergnat, Provençal and Vivaro-Alpine), more innovative

Pierre Bec divides the dialects into three groups:[68]

- Gascon, standing alone

- Southern Occitan (Languedocien and Provençal)

- Northern Occitan (Limousin, Auvergnat, Vivaro-Alpine)

In order to overcome the pitfalls of the traditional romanistic view, Bec proposed a "supradialectal" classification that groups Occitan with Catalan as a part of a wider Occitano-Romanic group. One such classification posits three groups:[69][70][71]

- "Arverno-Mediterranean" (arvèrnomediterranèu), same as Wheeler's northeastern group, i.e. Limousin, Auvergnat, Provençal and Vivaro-Alpine

- "Central Occitan" (occitan centrau), Languedocien, excepting the Southern Languedocien subdialect

- "Aquitano-Pyrenean" (aquitanopirenenc), Southern Languedocien, Gascon and Catalan

According to this view, Catalan is an ausbau language that became independent from Occitan during the 13th century, but originates from the Aquitano-Pyrenean group.

Domergue Sumien proposes a slightly different supradialectal grouping.[72]

- Arverno-Mediterranean (arvèrnomediterranèu), same as in Bec and Wheeler, divided further:

- Niçard-Alpine (niçardoaupenc), Vivaro-Alpine along with the Niçard subdialect of Provençal.

- Trans-Occitan (transoccitan), the remainder of Provençal along with Limousin and Auvergnat.

- Pre-Iberian (preïberic).

- Central Occitan (occitan centrau), same as in Bec.

- Aquitano-Pyrenean (aquitanopirenenc), same as in Bec.

Jewish dialects

[edit]Occitan has 3 dialects spoken by Jewish communities that are all now extinct.

Judeo-Gascon

[edit]A sociolect of the Gascon dialect spoken by Spanish and Portuguese Jews in Gascony.[73] It, like many other Jewish dialects and languages, contained large amounts of Hebrew loanwords.[74] It went extinct after World War 2 with the last speakers being elderly Jews in Bayonne. About 850 unique words and a few morphological and grammatical aspects of the dialect were transmitted to Southern Jewish French.[75]

Judeo-Provençal

[edit]Judeo-Provençal was a dialect of Occitan spoken by Jews in Provence. The dialect declined in usage after Jews were expelled from the area in 1498, and was probably extinct by the 20th century.

Judeo-Niçard

[edit]The least attested of the Judeo-Occitan dialects, Judeo-Niçard was spoken by the community of Jews living in Nice, who were descendants of Jewish immigrants from Provence, Piedmont, and other Mediterranean communities. Its existence is attested from a few documents from the 19th century. It contained significant influence in both vocabulary and grammar from Hebrew.[75]

Southern Jewish French

[edit]All three of these dialects have some influence in Southern Jewish French, a dialect of French spoken by Jews in southern France. Southern Jewish French is now estimated to only be spoken by about 50–100 people.[75]

IETF dialect tags

[edit]pro: Old Occitan (until the 14th century).sdt: Judeo-Occitan

Several IETF language variant tags have been registered:[76]

oc-aranese: Aranese.oc-auvern: Auvergnat.oc-cisaup: Cisalpine, northwestern Italy.oc-creiss: Croissantoc-gascon: Gascon.oc-lemosin: Leimousin.oc-lengadoc: Languedocien.oc-nicard: Niçard.oc-provenc: Provençal.oc-vivaraup: Vivaro-Alpine.

Codification

[edit]Standardization

[edit]All regional varieties of the Occitan language have a written form; thus, Occitan can be considered as a pluricentric language. Standard Occitan, also called occitan larg (i.e., 'wide Occitan') is a synthesis that respects and admits soft regional adaptations (which are based on the convergence of previous regional koinés).[72] The standardization process began with the publication of Gramatica occitana segon los parlars lengadocians ("Grammar of the Languedocien Dialect") by Louis Alibert (1935), followed by the Dictionnaire occitan-français selon les parlers languedociens ("French-Occitan dictionary according to Languedocien") by the same author (1966), completed during the 1970s with the works of Pierre Bec (Gascon), Robèrt Lafont (Provençal), and others. However, the process has not yet been completed as of the present.[clarification needed] Standardization is mostly supported by users of the classical norm. Due to the strong situation of diglossia, some users[who?] thusly reject the standardization process, and do not conceive Occitan as a language that can be standardized as per other standardized languages.[citation needed]

Writing system

[edit]There are two main linguistic norms currently used for Occitan, one (known as "classical") based on that of Medieval Occitan, and one (sometimes known as "Mistralian", due to its use by Frédéric Mistral) based on modern French orthography. Sometimes, there is conflict between users of each system.

- The classical norm (or less exactly classical orthography) has the advantage of maintaining a link with earlier stages of the language, and reflects the fact that Occitan is not a variety of French. It is used in all Occitan dialects. It also allows speakers of one dialect of Occitan to write intelligibly for speakers of other dialects (e.g. the Occitan for day is written jorn in the classical norm, but could be jour, joun, journ, or even yourn, depending on the writer's origin, in Mistralian orthography). The Occitan classical orthography and the Catalan orthography are quite similar: they show the very close ties of both languages. The digraphs lh and nh, used in the classical orthography, were adopted by the orthography of Portuguese, presumably by Gerald of Braga, a monk from Moissac, who became bishop of Braga in Portugal in 1047, playing a major role in modernizing written Portuguese using classical Occitan norms.[77]

- The Mistralian norm (or less exactly Mistralian orthography) has the advantage of being similar to that of French, in which most Occitan speakers are literate. Now, it is used mostly in the Provençal/Niçard dialect, besides the classical norm. It has also been used by a number of eminent writers, particularly in Provençal. However, it is somewhat impractical, because it is based mainly on the Provençal dialect and also uses many digraphs for simple sounds, the most notable one being ou for the [u] sound, as it is in French, written as o under the classical orthography.

There are also two other norms but they have a lesser audience. The Escòla dau Pò norm (or Escolo dóu Po norm) is a simplified version of the Mistralian norm and is used only in the Occitan Valleys (Italy), besides the classical norm. The Bonnaudian norm (or écriture auvergnate unifiée, EAU) was created by Pierre Bonnaud and is used only in the Auvergnat dialect, besides the classical norm.

| Classical norm | Mistralian norm | Bonnaudian norm | Escòla dau Pò norm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provençal Totei lei personas naisson liuras e egalas en dignitat e en drech. Son dotadas de rason e de consciéncia e li cau (/fau/) agir entre elei amb un esperit de frairesa. |

Provençal Tóuti li persouno naisson liéuro e egalo en dignita e en dre. Soun doutado de rasoun e de counsciènci e li fau agi entre éli em' un esperit de freiresso. |

||

| Niçard Provençal Toti li personas naisson liuri e egali en dignitat e en drech. Son dotadi de rason e de consciéncia e li cau agir entre eli emb un esperit de frairesa. |

Niçard Provençal Touti li persouna naisson liéuri e egali en dignità e en drech. Soun doutadi de rasoun e de counsciència e li cau agì entre eli em' un esperit de frairessa. |

||

| Auvergnat Totas las personas naisson liuras e egalas en dignitat e en dreit. Son dotadas de rason e de consciéncia e lor chau (/fau/) agir entre elas amb un esperit de frairesa. |

Auvergnat Ta la proussouna neisson lieura moé parira pà dïnessà mai dret. Son charjada de razou moé de cousiensà mai lhu fau arjî entremeî lha bei n'eime de freiressà. (Touta la persouna naisson lieura e egala en dïnetàt e en dreit. Soun doutada de razou e de cousiensà e lour chau ajî entre ela am en esprî de freiressà.) |

||

| Vivaro-Alpine Totas las personas naisson liuras e egalas en dignitat e en drech. Son dotaas de rason e de consciéncia e lor chal agir entre elas amb un esperit de fraternitat. |

Vivaro-Alpine Toutes les persounes naisoun liures e egales en dignità e en drech. Soun douta de razoun e de counsiensio e lour chal agir entre eels amb (/bou) un esperit de freireso. | ||

| Gascon Totas las personas que naishen liuras e egaus en dignitat e en dreit. Que son dotadas de rason e de consciéncia e que'us cau agir enter eras dab un esperit de hrairessa. |

Gascon (Febusian writing) Toutes las persounes que nachen libres e egaus en dinnitat e en dreyt. Que soun doutades de rasoû e de counscienci e qu'ous cau ayi entre eres dap û esperit de hrayresse. |

||

| Limousin Totas las personas naisson liuras e egalas en dignitat e en drech. Son dotadas de rason e de consciéncia e lor chau (/fau/) agir entre elas emb un esperit de frairesa. |

|||

| Languedocien Totas las personas naisson liuras e egalas en dignitat e en drech. Son dotadas de rason e de consciéncia e lor cal agir entre elas amb un esperit de frairesa. |

| French Tous les êtres humains naissent libres et égaux en dignité et en droits. Ils sont doués de raison et de conscience et doivent agir les uns envers les autres dans un esprit de fraternité.[78] |

Franco-Provençal Tôs los étres homans nêssont libros et ègals en dignitât et en drêts. Ils ant rêson et conscience et dêvont fâre los uns envèrs los ôtros dedens un èsprit de fraternitât.[78] |

Catalan Totes les persones neixen/naixen lliures i iguals en dignitat i en drets. Són dotades de raó i de consciència, i cal que es comportin fraternalment les unes amb les altres.[78] |

Spanish Todos los seres humanos nacen libres e iguales en dignidad y derechos y, dotados como están de razón y conciencia, deben comportarse fraternalmente los unos con los otros.[78] |

Portuguese Todos os seres humanos nascem livres e iguais em dignidade e direitos. Eles são dotados de razão e consciência, e devem comportar-se fraternalmente uns com os outros.[78] |

Italian Tutti gli esseri umani nascono liberi ed uguali in dignità e in diritti. Sono dotati di ragione e di coscienza e devono comportarsi fraternamente l'uno con l'altro.[78] |

English All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.[79] |

Note that Catalan version was translated from the Spanish, while the Occitan versions were translated from the French. The second part of the Catalan version may also be rendered as "Són dotades de raó i de consciència, i els cal actuar entre si amb un esperit de fraternitat", showing the similarities between Occitan and Catalan.

Orthography IETF subtags

[edit]Several IETF language subtags have been registered for the different orthographies:[76]

oc-grclass: Classical Occitan orthography.oc-grital: Italian-inspired Occitan orthography.oc-grmistr: Mistralian-inspired Occitan orthography.

Debates concerning linguistic classification and orthography

[edit]The majority of scholars think that Occitan constitutes a single language.[80] Some authors,[81] constituting a minority,[80] reject this opinion and even the name Occitan, thinking that there is a family of distinct lengas d'òc rather than dialects of a single language.

Many Occitan linguists and writers,[82] particularly those involved with the pan-Occitan movement centered on the Institut d'Estudis Occitans, disagree with the view that Occitan is a family of languages; instead they believe Limousin, Auvergnat, Languedocien, Gascon, Provençal and Vivaro-Alpine are dialects of a single language. Although there are indeed noticeable differences between these varieties, there is a very high degree of mutual intelligibility between them[83] partly because they share a common literary history; furthermore, academic and literary circles have identified them as a collective linguistic entity—the lenga d'òc—for centuries.[citation needed]

Some Provençal authors continue to support the view that Provençal is a separate language.[84] Nevertheless, the vast majority of Provençal authors and associations think that Provençal is a part of Occitan.[85]

This debate about the status of Provençal should not be confused with the debate concerning the spelling of Provençal.

- The classical orthography is phonemic and diasystemic, and thus more pan-Occitan. It can be used for (and adapted to) all Occitan dialects and regions, including Provençal. Its supporters think that Provençal is a part of Occitan.

- The Mistralian orthography of Provençal is more or less phonemic but not diasystemic and is closer to the French spelling and therefore more specific to Provençal; its users are divided between the ones who think that Provençal is a part of Occitan and the ones who think that Provençal is a separate language.

For example, the classical system writes Polonha, whereas the Mistralian spelling system has Poulougno, for [puˈluɲo], 'Poland'.

The question of Gascon is similar. Gascon presents a number of significant differences from the rest of the language; but, despite these differences, Gascon and other Occitan dialects have very important common lexical and grammatical features, so authors such as Pierre Bec argue that they could never be considered as different as, for example, Spanish and Italian.[86] In addition, Gascon's being included in Occitan despite its particular differences can be justified because there is a common elaboration (Ausbau) process between Gascon and the rest of Occitan.[80] The vast majority of the Gascon cultural movement considers itself as a part of the Occitan cultural movement.[87][88] And the official status of Val d'Aran (Catalonia, Spain), adopted in 1990, says that Aranese is a part of Gascon and Occitan. A grammar of Aranese by Aitor Carrera, published in 2007 in Lleida, presents the same view.[89]

The exclusion of Catalan from the Occitan sphere, even though Catalan is closely related, is justified because there has been a consciousness of its being different from Occitan since the later Middle Ages and because the elaboration (Ausbau) processes of Catalan and Occitan (including Gascon) have been quite distinct since the 20th century. Nevertheless, other scholars point out that the process that led to the affirmation of Catalan as a distinct language from Occitan started during the period when the pressure to include Catalan-speaking areas in a mainstream Spanish culture was at its greatest.[90]

The answer to the question of whether Gascon or Catalan should be considered dialects of Occitan or separate languages has long been a matter of opinion or convention, rather than based on scientific ground. However, two recent studies support Gascon's being considered a distinct language. For the first time, a quantifiable, statistics-based approach was applied by Stephan Koppelberg in attempt to solve this issue.[91] Based on the results he obtained, he concludes that Catalan, Occitan, and Gascon should all be considered three distinct languages. More recently, Y. Greub and J.P. Chambon (Sorbonne University, Paris) demonstrated that the formation of Proto-Gascon was already complete at the eve of the 7th century, whereas Proto-Occitan was not yet formed at that time.[92] These results induced linguists to do away with the conventional classification of Gascon, favoring the "distinct language" alternative.[citation needed] Both studies supported the early intuition of the late Kurt Baldinger, a specialist of both medieval Occitan and medieval Gascon, who recommended that Occitan and Gascon be classified as separate languages.[93][94]

Linguistic characterization

[edit]This section includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2011) |

Jules Ronjat has sought to characterize Occitan with 19 principal, generalizable criteria. Of those, 11 are phonetic, five morphologic, one syntactic, and two lexical. For example, close rounded vowels are rare or absent in Occitan. This characteristic often carries through to an Occitan speaker's French, leading to a distinctive méridional accent. Unlike French, it is a pro-drop language, allowing the omission of the subject (canti: I sing; cantas you sing)—though, at least in Gascon, the verb must be preceded by an "enunciative" in place of the pronoun, e for questions, be for observations, que for other occasions: e.g., que soi (I am), E qu'ei? (He/she is?), Be qu'èm. (We are.).[95] Among these 19 discriminating criteria, 7 are different from Spanish, 8 from Italian, 12 from Franco-Provençal, and 16 from French.

Features of Occitan

[edit]Most features of Occitan are shared with either French or Catalan, or both.

Features of Occitan as a whole

[edit]Examples of pan-Occitan features shared with French, but not Catalan:

- Latin ū [uː] (Vulgar Latin /u/) changed to /y/, as in French (Lat. dv̄rvm > Oc. dur).

- Vulgar Latin /o/ changed to /u/, first in unstressed syllables, as in Eastern Catalan (Lat. romānvs > Oc. roman [ruˈma]), then in stressed syllables (Lat. flōrem > Oc. flor [fluɾ]).

Examples of pan-Occitan features shared with Catalan, but not French:

- Stressed Latin a was preserved (Lat. mare > Oc. mar, Fr. mer).

- Intervocalic -t- was lenited to /d/ rather than lost (Lat. vitam > Oc. vida, Fr. vie).

Examples of pan-Occitan features not shared with Catalan or French:

- Original /aw/ preserved.

- Final /a/ becomes /ɔ/ (note in Valencian (Catalan), /ɔ/ may appear in word-final unstressed position, in a process of vowel harmony).

- Low-mid /ɛ/ and /ɔ/ diphthongized before velars. /ɛ/ generally becomes /jɛ/; /ɔ/ originally became /wɔ/ or /wɛ/, but has since usually undergone further fronting (e.g. to [ɥɛ], [ɥɔ], [jɔ], [œ], [ɛ], [ɥe], [we], etc.). Diphthongization also occurred before palatals, as in French and Catalan.

- Various assimilations in consonant clusters (e.g. ⟨cc⟩ in Occitan, pronounced /utsiˈta/ in conservative Languedocien).

Features of some Occitan dialects

[edit]Examples of dialect-specific features of the northerly dialects shared with French, but not Catalan:

- Palatalization of ca-, ga- to /tʃa, dʒa/.

- Vocalization of syllable-final /l/ to /w/.

- Loss of final consonants.

- Vocalization of syllable-final nasals to nasal vowels.

- Uvularization of some or all ⟨r⟩ sounds.

Examples of dialect-specific features of the southerly dialects (or some of them) shared with Catalan, but not French:

- Latin -mb-,-nd- become /m, n/.

- Betacism: /b/ and /v/ merge (feature shared with Spanish and some Catalan dialects; except for Balearic, Valencian and Algherese Catalan, where /v/ is preserved).

- Intervocalic voiced stops /b d ɡ/ (from Latin -p-, -t, -c-) become voiced fricatives [β ð ɣ].

- Loss of word-final single /n/ (but not /nn/, e.g. an "year" < ānnvm).

Examples of Gascon-specific features not shared with French or Catalan:

- Latin initial /f/ changed into /h/ (Lat. filivm > Gasc. hilh). This also happened in medieval Spanish, although the /h/ was eventually lost, or reverted to /f/ (before a consonant). The Gascon ⟨h⟩ has retained its aspiration.

- Loss of /n/ between vowels. This also happened in Portuguese and Galician (and moreover also in Basque).

- Change of -ll- to ⟨r⟩ /ɾ/, or ⟨th⟩ word-finally (originally the voiceless palatal stop /c/, but now generally either /t/ or /tʃ/, depending on the word). This is a unique characteristic of Gascon and of certain Aragonese dialects.

Examples of other dialect-specific features not shared with French or Catalan:

- Merging of syllable-final nasals to /ŋ/. This appears to represent a transitional stage before nasalization, and occurs especially in the southerly dialects other than Gascon (which still maintains different final nasals, as in Catalan).

- Former intervocalic /ð/ (from Latin -d-) becomes /z/ (most dialects, but not Gascon). This appears to have happened in primitive Catalan as well, but Catalan later deleted this sound or converted it to /w/.

- Palatalization of /jt/ (from Latin ct) to /tʃ/ in most dialects or /(j)t/: lach vs lait (Gascon lèit) 'milk', lucha vs luta (Gascon luta) 'fight'.

- Weakening of /l/ to /r/ in the Vivaro-Alpine dialect.

Comparison with other Romance languages and English

[edit]| Latin (all nouns in the ablative case) |

Occitan (including main regional varieties) |

Catalan | French | Norman | Romansh (Rumantsch Grischun) | Ladin (Gherdëina) | Lombard | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Sardinian | Romanian | English |

| cantare | cantar (chantar) | cantar | chanter | canter, chanter | chantar | cianté | cantà | cantare | cantar | cantar | cantare | cânta(re) | '(to) sing' |

| capra | craba (chabra, chaura) | cabra | chèvre | quièvre | chaura | cëura | cavra | capra | cabra | cabra | craba | capră | 'goat' |

| clave | clau | clau | clé, clef | clef | clav | tle | ciav | chiave | llave | chave | crae | cheie | 'key' |

| ecclesia, basilica | glèisa (esglèisa, glèia) | església | église | église | baselgia | dlieja | giesa | chiesa | iglesia | igreja | gresia/creia | biserică | 'church' |

| formatico (Vulgar Latin), caseo | formatge (fromatge, hormatge) | formatge | fromage | froumage, fourmage | chaschiel | ciajuel | furmai/furmagg | formaggio | queso | queijo | casu | caș | 'cheese' |

| lingva | lenga (lengua, luenga, linga) | llengua | langue | langue | lingua | lenga, rujeneda | lengua | lingua | lengua | língua | limba | limbă | 'tongue, language' |

| nocte | nuèch (nuèit, nueit, net, nuòch) | nit | nuit | nît | notg | nuet | nocc | notte | noche | noite | nothe | noapte | 'night' |

| platea | plaça | plaça | place | plache | plazza | plaza | piassa | piazza | plaza | praça | pratza | piață[96] | 'square, plaza' |

| ponte | pont (pònt) | pont | pont | pont | punt | puent | punt | ponte | puente | ponte | ponte | punte (small bridge) | 'bridge' |

Lexicon

[edit]A comparison of terms and word counts between languages is not easy, as it is impossible to count the number of words in a language. (See Lexicon, Lexeme, Lexicography for more information.)

Some have claimed around 450,000 words exist in the Occitan language,[97] a number comparable to English (the Webster's Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged with 1993 addenda reaches 470,000 words, as does the Oxford English Dictionary, Second edition). The Merriam-Webster website estimates that the number is somewhere between 250,000 and 1 million words.[citation needed]

The magazine Géo (2004, p. 79) claims that American English literature can be more easily translated into Occitan than French, excluding modern technological terms that both languages have integrated.[citation needed]

A comparison of the lexical content can find more subtle differences between the languages. For example, Occitan has 128 synonyms related to cultivated land, 62 for wetlands, and 75 for sunshine (Géo). The language went through an eclipse during the Industrial Revolution, as the vocabulary of the countryside became less important. At the same time, it was disparaged as a patois. Nevertheless, Occitan has also incorporated new words into its lexicon to describe the modern world. The Occitan word for web (as in World Wide Web) is oèb, for example.

Differences between Occitan and Catalan

[edit]The separation of Catalan from Occitan is seen by some[citation needed] as largely politically (rather than linguistically) motivated. However, the variety that has become standard Catalan differs from the one that has become standard Occitan in a number of ways. Here are just a few examples:

- Phonology

- Standard Catalan (based on Central Eastern Catalan) is unique in that Latin short e developed into a close vowel /e/ (é) and Latin long e developed into an open vowel /ɛ/ (è); that is precisely the reverse of the development that took place in Western Catalan dialects and the rest of the Romance languages, including Occitan. Thus Standard Catalan ésser [ˈesə] corresponds to Occitan èsser/èstre [ˈɛse/ˈɛstre] 'to be;' Catalan carrer [kəˈre] corresponds to Occitan carrièra [karˈjɛɾo̞] 'street', but it is also carriera [karˈjeɾo̞], in Provençal.

- The distinctly Occitan development of word-final -a, pronounced [o̞] in standard Occitan (chifra 'figure' [ˈtʃifro̞]), did not occur in general Catalan (which has xifra [ˈʃifrə]). However, some Occitan varieties also lack that feature, and some Catalan (Valencian) varieties have the [ɔ] pronunciation, mostly by vowel harmony.

- When in Catalan word stress falls in the antepenultimate syllable, in Occitan the stress is moved to the penultimate syllable: for example, Occitan pagina [paˈdʒino̞] vs. Catalan pàgina [ˈpaʒinə], "page". However, there are exceptions. For example, some varieties of Occitan (such as that of Nice) keep the stress on the antepenultimate syllable (pàgina), and some varieties of Catalan (in Northern Catalonia) put the stress on the penultimate syllable (pagina).

- Diphthongization has evolved in different ways: Occitan paire vs. Catalan pare 'father;' Occitan carrièra (carrèra, carrèira) vs. Catalan carrera.

- Although some Occitan dialects lack the voiceless postalveolar fricative phoneme /ʃ/, others such as southwestern Occitan have it: general Occitan caissa [ˈkajso̞] vs. Catalan caixa [ˈkaʃə] and southwestern Occitan caissa, caisha [ˈka(j)ʃo̞], 'box.' Nevertheless, some Valencian dialects like Northern Valencian lack that phoneme too and generally substitute /jsʲ/: caixa [ˈkajʃa] (Standard Valencian) ~ [ˈkajsʲa] (Northern Valencian).

- Occitan has developed the close front rounded vowel /y/ as a phoneme, often (but not always) corresponding to Catalan /u/: Occitan musica [myˈziko̞] vs. Catalan música [ˈmuzikə].

- The distribution of palatal consonants /ʎ/ and /ɲ/ differs in Catalan and part of Occitan: while Catalan permits them in word-final position, in central Occitan they are neutralized to [l] and [n] (Central Occitan filh [fil] vs. Catalan fill [fiʎ], 'son'). Similarly, Algherese Catalan neutralizes palatal consonants in word-final position as well. Non-central varieties of Occitan, however, may have a palatal realization (e.g. filh, hilh [fiʎ, fij, hiʎ]).

- Furthermore, many words that start with /l/ in Occitan start with /ʎ/ in Catalan: Occitan libre [ˈliβɾe] vs. Catalan llibre [ˈʎiβɾə], 'book.' That feature is perhaps one of the most distinctive characteristics of Catalan amongst the Romance languages, shared only with Asturian, Leonese and Mirandese. However, some transitional varieties of Occitan, near the Catalan area, also have initial /ʎ/.

- While /l/ is always clear in Occitan, in Catalan it tends to be velarized [ɫ] ("dark l"). In coda position, /l/ has tended to be vocalized to [w] in Occitan, while remained dark in Catalan.

- Standard Eastern Catalan has a neutral vowel [ə] whenever a or e occur in unstressed position (passar [pəˈsa], 'to happen', but passa [ˈpasə], 'it happens'), and also [u] whenever o or u occur in unstressed position, e.g. obrir [uˈβɾi], 'to open', but obre [ˈɔβɾə], 'you open'. However, that does not apply to Western Catalan dialects, whose vowel system usually retains the a/e distinction in unstressed position, or to Northern Catalan dialects, whose vowel system does not retain the o/u distinction in stressed position, much like Occitan.

- Morphology

- Verb conjugation is slightly different, but there is a great variety amongst dialects. Medieval conjugations were much closer. A characteristic difference is the ending of the second person plural, which is -u in Catalan but -tz in Occitan.

- Occitan tends to add an analogical -a to the feminine forms of adjectives that are invariable in standard Catalan: for example, Occitan legal / legala vs. Catalan legal / legal.

- Catalan has a distinctive past tense formation, known as the 'periphrastic preterite', formed from a variant of the verb 'to go' followed by the infinitive of the verb: donar 'to give,' va donar 'he gave.' That has the same value as the 'normal' preterite shared by most Romance languages, deriving from the Latin perfect tense: Catalan donà 'he gave.' The periphrastic preterite, in Occitan, is an archaic or a very local tense.

- Orthography

- The writing systems of the two languages differ slightly. The modern Occitan spelling recommended by the Institut d'Estudis Occitans and the Conselh de la Lenga Occitana is designed to be a pan-Occitan system, and the Catalan system recommended by the Institut d'Estudis Catalans and Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua is specific to Catalan and Valencian. For example, in Catalan, word-final -n is omitted, as it is not pronounced in any dialect of Catalan (Català, Occità); central Occitan also drops word-final -n, but it is retained in the spelling, as some eastern and western dialects of Occitan still have it (Catalan, Occitan). Some digraphs are also written in a different way such as the sound /ʎ/, which is ll in Catalan (similar to Spanish) and lh in Occitan (similar to Portuguese) or the sound /ɲ/ written ny in Catalan and nh in Occitan.

Occitano-Romance linguistic group

[edit]Despite these differences, Occitan and Catalan remain more or less mutually comprehensible, especially when written – more so than either is with Spanish or French, for example, although this is mainly a consequence of using the classical (orthographical) norm of the Occitan, which is precisely focused in showing the similarities between the Occitan dialects with Catalan. Occitan and Catalan form a common diasystem (or a common Abstandsprache), which is called Occitano-Romance, according to the linguist Pierre Bec.[98] Speakers of both languages share early historical and cultural heritage.

The combined Occitano-Romance area is 259,000 km2, with a population of 23 million. However, the regions are not equal in terms of language speakers. According to Bec 1969 (pp. 120–121), in France, no more than a quarter of the population in counted regions could speak Occitan well, though around half understood it; it is thought that the number of Occitan users has decreased dramatically since then. By contrast, in the Catalonia administered by the Government of Catalonia, nearly three-quarters of the population speak Catalan and 95% understand it.[99]

Preservation

[edit]In the modern era, Occitan has become a rare and highly threatened language. Its users are clustered almost exclusively in Southern France, and it is unlikely that any monolingual speakers remain. In the early 1900s, the French government attempted to restrict the use and teaching of many minority languages, including Occitan, in public schools. While the laws have since changed, with bilingual education returning for regions with unique languages in 1993, the many years of restrictions had already caused serious decline in the number of Occitan speakers. The majority of living speakers are older adults.[100][101][102]

Samples

[edit]

One of the most notable passages of Occitan in Western literature occurs in the 26th canto of Dante's Purgatorio in which the troubadour Arnaut Daniel responds to the narrator:

- Tan m'abellís vostre cortés deman, / qu'ieu no me puesc ni voill a vos cobrire. / Ieu sui Arnaut, que plor e vau cantan; / consirós vei la passada folor, / e vei jausen lo joi qu'esper, denan. / Ara vos prec, per aquella valor / que vos guida al som de l'escalina, / sovenha vos a temps de ma dolor.

- Modern Occitan: Tan m'abelís vòstra cortesa demanda, / que ieu non-pòdi ni vòli m'amagar de vos. / Ieu soi Arnaut, que plori e vau cantant; / consirós vesi la foliá passada, / e vesi joiós lo jorn qu'espèri, davant. / Ara vos prègui, per aquela valor / que vos guida al som de l'escalièr, / sovenhatz-vos tot còp de ma dolor.

The above strophe translates to:

- So pleases me your courteous demand, / I cannot and I will not hide me from you. / I am Arnaut, who weep and singing go;/ Contrite I see the folly of the past, / And joyous see the hoped-for day before me. / Therefore do I implore you, by that power/ Which guides you to the summit of the stairs, / Be mindful to assuage my suffering!

Another notable Occitan quotation, this time from Arnaut Daniel's own 10th Canto:

- "Ieu sui Arnaut qu'amas l'aura

- e chatz le lebre ab lo bou

- e nadi contra suberna"

Modern Occitan:

- "Ieu soi Arnaut qu'aimi l'aura

- e caci [chaci] la lèbre amb lo buòu

- e nadi contra subèrna.

Translation:

- "I am Arnaut who loves the wind,

- and chases the hare with the ox,

- and swims against the torrent."

French writer Victor Hugo's classic Les Misérables also contains some Occitan. In Part One, First Book, Chapter IV, "Les œuvres semblables aux paroles", one can read about Monseigneur Bienvenu:

- "Né provençal, il s'était facilement familiarisé avec tous les patois du midi. Il disait: — E ben, monsur, sètz saget? comme dans le bas Languedoc. — Ont anaratz passar? comme dans les basses Alpes. — Pòrti un bon moton amb un bon formatge gras, comme dans le haut Dauphiné. [...] Parlant toutes les langues, il entrait dans toutes les âmes."

Translation:

- "Born a Provençal, he easily familiarized himself with the dialect of the south. He would say, E ben, monsur, sètz saget? as in lower Languedoc; Ont anaratz passar? as in the Basses-Alpes; Pòrti un bon moton amb un bon formatge gras as in upper Dauphiné. [...] As he spoke all tongues, he entered into all hearts."

- E ben, monsur, sètz saget?: So, Mister, everything's fine?

- Ont anaratz passar?: Which way will you go?

- Pòrti un bon moton amb un bon formatge gras: I brought some fine mutton with a fine fat cheese

The Spanish playwright Lope de Rueda included a Gascon servant for comical effect in one of his short pieces, La generosa paliza.[103]

John Barnes's Thousand Cultures science fiction series (A Million Open Doors, 1992; Earth Made of Glass, 1998; The Merchants of Souls, 2001; and The Armies of Memory, 2006), features Occitan. So does the 2005 best-selling novel Labyrinth by English author Kate Mosse. It is set in Carcassonne, where she owns a house and spends half of the year.

The French composer Joseph Canteloube created five sets of folk songs entitled Songs of the Auvergne, in which the lyrics are in the Auvergne dialect of Occitan. The orchestration strives to conjure vivid pastoral scenes of yesteryear.

Michael Crichton features Occitan in his Timeline novel.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Occitan at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

Judeo-Occitan at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ a b Bernissan, Fabrice (2012). "Combien l'occitan compte de locuteurs en 2012?". Revue de Linguistique Romane (in French). 76: 467–512.

- ^ a b Martel, Philippe (December 2007). "Qui parle occitan ?". Langues et cité (in French). No. 10. Observation des pratiques linguistiques. p. 3. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

De fait, le nombre des locuteurs de l'occitan a pu être estimé par l'INED dans un premier temps à 526 000 personnes, puis à 789 000 ("In fact, the number of Occitan speakers was estimated by the French Demographics Institute at 526,000 people, then 789,000")

- ^ Enrico Allasino; Consuelo Ferrier; Sergio Scamuzzi; Tullio Telmon (2005). "Le Lingue del Piemonte" (PDF). IRES. 113: 71. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2020 – via Gioventura Piemontèisa.

- ^ Enquesta d'usos lingüístics de la població 2008 [Survey of Language Use of the Population 2008] (in Catalan), Statistical Institute of Catalonia, 2009, archived from the original on 17 October 2020, retrieved 4 March 2020

- ^ Norme in materia di tutela delle minoranze linguistiche storiche, Italian parliament, archived from the original on 2 May 2012, retrieved 18 June 2014

- ^ CLO's statements in Lingüistica Occitana (online review of Occitan linguistics).Lingüistica Occitana: Preconizacions del Conselh de la Lenga Occitana (PDF), 2007, archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2020, retrieved 17 March 2020

- ^ "Page d'accueil". Région Nouvelle-Aquitaine – Aquitaine Limousin Poitou-Charentes. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ "Reconeishença der Institut d'Estudis Aranesi coma academia e autoritat lingüistica der occitan, aranés en Aran" [Recognition of the Institute of Aranese Studies as an academy and linguistic authority of Occitan, Aranese in Aran]. Conselh Generau d'Aran (in Occitan). 2 April 2014. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ 18

- ^ 18

- ^ "Occitan". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Occitan". Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary (7th ed.). 2005.

- ^ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Gardiol". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ^ Friend, Julius W. (2012). Stateless Nations: Western European Regional Nationalisms and the Old Nations. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-230-36179-9. Retrieved 3 October 2025.

- ^ Smith & Bergin 1984, p. 9

- ^ Mica GBM (2025), Lo Panoccinari (Volume Four), p. 789.

- ^ As stated in its Statute of Autonomy approved. See Article 6.5 in the Parlament-cat.net Archived 26 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine, text of the 2006 Statute of Catalonia (PDF)

- ^ Dalby, Andrew (1998). "Occitan". Dictionary of Languages (1st ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing plc. p. 468. ISBN 0-7475-3117-X. Archived from the original on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2006.

- ^ "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in danger". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- ^ Badia i Margarit, Antoni M. (1995). Gramàtica de la llengua catalana: Descriptiva, normativa, diatòpica, diastràtica. Barcelona: Proa., 253.1 (in Catalan)

- ^ Smith & Bergin 1984, p. 2

- ^ Lapobladelduc.org Archived 6 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine, "El nom de la llengua". The name of the language, in Catalan

- ^ Anglade 1921, p. 10: Sur Occitania ont été formés les adjectifs latins occitanus, occitanicus et les adjectifs français occitanique, occitanien, occitan (ce dernier terme plus récent), qui seraient excellents et qui ne prêteraient pas à la même confusion que provençal.

- ^ Anglade 1921, p. 7.

- ^ Camille Chabaneau et al, Histoire générale de Languedoc, 1872, p. 170: Au onzième, douzième et encore parfois au XIIIe siècle, on comprenait sous le nom de Provence tout le territoire de l'ancienne Provincia Romana et même de l'Aquitaine.

- ^ Anglade 1921, p. 7: Ce terme fut surtout employé en Italie.

- ^ Raynouard, François Juste Marie (1817). Choix des poésies originales des troubadours (Volume 2) (in French). Paris: F. Didot. p. 40. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ Raynouard, François Juste Marie (1816). Choix des poésies originales des troubadours (Volume 1) (in French). Paris: F. Didot. p. vij. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ Raynouard, François Juste Marie (1817). Choix des poésies originales des troubadours (Volume 2) (in French). Paris: F. Didot. p. cxxxvij. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2013.: "Ben ha mil e cent (1100) ancs complí entierament / Que fo scripta l'ora car sen al derier temps."

- ^ Charles Knight, Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, Vol. XXV, 1843, p. 308: "At one time the language and poetry of the troubadours were in fashion in most of the courts of Europe."

- ^ Bec 1963.

- ^ a b c Bec 1963, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Cierbide Martinena, Ricardo (1996). "Convivencia histórica de lenguas y culturas en Navarra". Caplletra: Revista Internacional de Filología (in Spanish) (20). València (etc) : Institut Interuniversitari de Filologia Valenciana; Abadia de Montserrat: 247. ISSN 0214-8188. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ Cierbide Martinena, Ricardo (1998). "Notas gráfico-fonéticas sobre la documentación medieval navarra". Príncipe de Viana (in Spanish). 59 (214): 524. ISSN 0032-8472. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ Cierbide Martinena, Ricardo (1996). "Convivencia histórica de lenguas y culturas en Navarra". Caplletra: Revista Internacional de Filología (in Spanish) (20). València (etc) : Institut Interuniversitari de Filologia Valenciana; Abadia de Montserrat: 247–249. ISSN 0214-8188. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ Jurio, Jimeno (1997). Navarra: Historia del Euskera. Tafalla: Txalaparta. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-84-8136-062-2.

- ^ "Licenciado Andrés de Poza y Yarza". EuskoMedia Fundazioa. Archived from the original on 3 July 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2010. Poza quotes the Basques inhabiting lands as far east as the River Gallego in the 16th century.

- ^ Cierbide Martinena, Ricardo (1996). "Convivencia histórica de lenguas y culturas en Navarra". Caplletra: Revista Internacional de Filología (in Spanish) (20). València (etc) : Institut Interuniversitari de Filologia Valenciana; Abadia de Montserrat: 249. ISSN 0214-8188. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2010.