Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Social mobility

View on Wikipedia

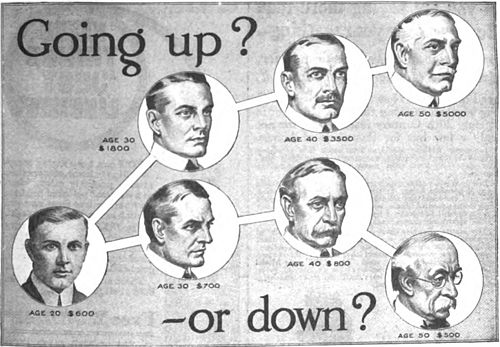

Social mobility is the movement of individuals, families, households or other categories of people within or between social strata in a society.[1] It is a change in social status relative to one's current social location within a given society. This movement occurs between layers or tiers in an open system of social stratification. Open stratification systems are those in which at least some value is given to achieved status characteristics in a society. The movement can be in a downward or upward direction.[2] Markers for social mobility such as education and class, are used to predict, discuss and learn more about an individual or a group's mobility in society.

Typology

[edit]Mobility is most often quantitatively measured in terms of change in economic mobility such as changes in income or wealth. Occupation is another measure used in researching mobility which usually involves both quantitative and qualitative analysis of data, but other studies may concentrate on social class.[3] Mobility may be intragenerational, within the same generation or intergenerational, between different generations.[4] Intragenerational mobility is less frequent, representing "rags to riches" cases in terms of upward mobility. Intergenerational upward mobility is more common where children or grandchildren are in economic circumstances better than those of their parents or grandparents. In the US, this type of mobility is described as one of the fundamental features of the "American Dream" even though there is less such mobility than almost all other OECD countries.[5]

Mobility can also be defined in terms of relative or absolute mobility. Absolute mobility measures a person’s progress in areas such as education, health, housing, income, and job opportunities, comparing it to a starting point—usually the previous generation. As technological advancements and economic development increase, so do income levels and living conditions for most people. In absolute terms, people around the world, on average, are living better today than in the past and, in that sense, have experienced absolute mobility.

Relative mobility examines a person’s movement compared to others within the same cohort. In more advanced economies and OECD countries, there is generally more room for absolute mobility than for relative mobility. This means a person from an average-status background may remain average relative to their peers (showing no relative mobility) but still experience a gradual increase in living standards as the overall social average rises over time.

There is also an idea of stickiness concerning mobility. This is when an individual is no longer experiencing relative mobility and it occurs mostly at the ends. At the bottom end of the socioeconomic ladder, parents cannot provide their children with the necessary resources or opportunity to enhance their lives. As a result, they remain on the same ladder rung as their parents. On the opposite side of the ladder, the high socioeconomic status (SES) parents have the necessary resources and opportunities to ensure that their children also remain in same ladder rung as them.[6] In East Asian countries this is exemplified by the concept of familial karma.[1][clarification needed]

Social status and social class

[edit]Social mobility is highly dependent on the overall structure of social statuses and occupations in a given society.[7] The extent of differing social positions and the manner in which they fit together or overlap provides the overall social structure of such positions. Add to this the differing dimensions of status, such as Max Weber's delineation[8] of economic stature, prestige, and power and we see the potential for complexity in a given social stratification system. Such dimensions within a given society can be seen as independent variables that can explain differences in social mobility at different times and places in different stratification systems. The same variables that contribute as intervening variables to the valuation of income or wealth and that also affect social status, social class, and social inequality do affect social mobility. These include sex or gender, race or ethnicity, and age.[9]

Education provides one of the most promising chances of upward social mobility and attaining a higher social status, regardless of current social standing. However, the stratification of social classes and high wealth inequality directly affects the educational opportunities and outcomes. In other words, social class and a family's socioeconomic status directly affect a child's chances for obtaining a quality education and succeeding in life. By age five, there are significant developmental differences between low, middle, and upper class children's cognitive and noncognitive skills.[10]

Among older children, evidence suggests that the gap between high- and low-income primary- and secondary-school students has increased by almost 40 percent over the past thirty years. These differences persist and widen into young adulthood and beyond. Just as the gap in K–12 test scores between high- and low-income students is growing, the difference in college graduation rates between the rich and the poor is also growing. Although the college graduation rate among the poorest households increased by about 4 percentage points between those born in the early 1960s and those born in the early 1980s, over this same period, the graduation rate increased by almost 20 percentage points for the wealthiest households.[10]

Average family income, and social status, have both seen a decrease for the bottom third of all children between 1975 and 2011. The 5th percentile of children and their families have seen up to a 60% decrease in average family income.[10] The wealth gap between the rich and the poor, the upper and lower class, continues to increase as more middle-class people get poorer and the lower-class get even poorer. As the socioeconomic inequality continues to increase in the United States, being on either end of the spectrum makes a child more likely to remain there and never become socially mobile.

A child born to parents with income in the lowest quintile is more than ten times more likely to end up in the lowest quintile than the highest as an adult (43 percent versus 4 percent). And, a child born to parents in the highest quintile is five times more likely to end up in the highest quintile than the lowest (40 percent versus 8 percent).[10]

This may be partly due to lower- and working-class parents, where neither is educated above high school diploma level, spending less time on average with their children in their earliest years of life and not being as involved in their children's education and time out of school. This parenting style, known as "accomplishment of natural growth" differs from the style of middle-class and upper-class parents, with at least one parent having higher education, known as "cultural cultivation".[11]

More affluent social classes are able to spend more time with their children at early ages, and children receive more exposure to interactions and activities that lead to cognitive and non-cognitive development: things like verbal communication, parent-child engagement and being read to daily. These children's parents are much more involved in their academics and their free time; placing them in extracurricular activities which develop not only additional non-cognitive skills but also academic values, habits, and abilities to better communicate and interact with authority figures. Enrollment in so many activities can often lead to frenetic family lives organized around transporting children to their various activities. Lower class children often attend lower quality schools, receive less attention from teachers and ask for help much less than their higher class peers.[12]

The chances for social mobility are primarily determined by the family a child is born into. Today, the gaps seen in both access to education and educational success (graduating from a higher institution) is even larger. Today, while college applicants from every socioeconomic class are equally qualified, 75% of all entering freshmen classes at top-tier American institutions belong to the uppermost socioeconomic quartile. A family's class determines the amount of investment and involvement parents have in their children's educational abilities and success from their earliest years of life,[12] leaving low-income students with less chance for academic success and social mobility due to the effects that the common parenting style of the lower and working-class have on their outlook on and success in education.[12]

Class cultures and social networks

[edit]These differing dimensions of social mobility can be classified in terms of differing types of capital that contribute to changes in mobility. Cultural capital, a term first coined by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu distinguishes between the economic and cultural aspects of class. Bourdieu described three types of capital that place a person in a certain social category: economic capital; social capital; and cultural capital. Economic capital includes economic resources such as cash, credit, and other material assets. Social capital includes resources one achieves based on group membership, networks of influence, relationships and support from other people.[13]

Cultural capital is any advantage a person has that gives them a higher status in society, such as education, skills, or any other form of knowledge. Usually, people with all three types of capital have a high status in society. Bourdieu found that the culture of the upper social class is oriented more toward formal reasoning and abstract thought. The lower social class is geared more towards matters of facts and the necessities of life. He also found that the environment in which a person develops has a large effect on the cultural resources that a person will have.[13]

The cultural resources a person has obtained can heavily influence a child's educational success. It has been shown that students raised under the concerted cultivation approach have "an emerging sense of entitlement" which leads to asking teachers more questions and being a more active student, causing teachers to favor students raised in this manner.[14] This childrearing approach which creates positive interactions in the classroom environment is in contrast with the natural growth approach to childrearing. In this approach, which is more common amongst working-class families, parents do not focus on developing the special talents of their individual children, and they speak to their children in directives.[14]

Due to this, it is rarer for a child raised in this manner to question or challenge adults and conflict arises between childrearing practices at home and school. Children raised in this manner are less inclined to participate in the classroom setting and are less likely to go out of their way to positively interact with teachers and form relationships. However, the greater freedom of working-class children gives them a broader range of local playmates, closer relationships with cousins and extended family, less sibling rivalry, fewer complaints to their parents of being bored, and fewer parent-child arguments.[14]

In the United States, links between minority underperformance in schools have been made with a lacking in the cultural resources of cultural capital, social capital and economic capital, yet inconsistencies persist even when these variables are accounted for. "Once admitted to institutions of higher education, African Americans and Latinos continued to underperform relative to their white and Asian counterparts, earning lower grades, progressing at a slower rate and dropping out at higher rates. More disturbing was the fact that these differentials persisted even after controlling for obvious factors such as SAT scores and family socioeconomic status".[15]

The theory of capital deficiency is among the most recognized explanations for minority underperformance academically—that for whatever reason they simply lack the resources to find academic success.[16] One of the largest factors for this, aside from the social, economic, and cultural capital mentioned earlier, is human capital. This form of capital, identified by social scientists only in recent years, has to do with the education and life preparation of children. "Human capital refers to the skills, abilities and knowledge possessed by specific individuals".[17]

This allows college-educated parents who have large amounts of human capital to invest in their children in certain ways to maximize future success—from reading to them at night to possessing a better understanding of the school system which causes them to be less deferential to teachers and school authorities.[16] Research also shows that well-educated black parents are less able to transmit human capital to their children when compared to their white counterparts, due to a legacy of racism and discrimination.[16]

Markers

[edit]Health

[edit]The term "social gradient" in health refers to the idea that the inequalities in health are connected to the social status a person has.[18] Two ideas concerning the relationship between health and social mobility are the social causation hypothesis and the health selection hypothesis. These hypotheses explore whether health dictates social mobility or whether social mobility dictates quality of health. The social causation hypothesis states that social factors, such as individual behavior and the environmental circumstances, determine an individual's health. Conversely, the health selection hypothesis states that health determines what social stratum an individual will be in.[19]

There has been a lot of research investigating the relationship between socioeconomic status and health and which has the greater influence on the other. A recent study has found that the social causation hypothesis is more empirically supported than the health selection hypothesis. Empirical analysis shows no support for the health selection hypothesis.[20] Another study found support for either hypotheses depends on which lens the relationship between SES and health is being looked through. The health selection hypothesis is supported when people look at SES and health through the labor market lens. One possible reason for this is that health dictates an individual's productivity and to a certain extent if the individual is employed. While, the social causation hypothesis is supported when looking at health and socioeconomic status relationship through an education and income lenses.[21]

Education

[edit]The systems of stratification that govern societies hinder or allow social mobility. Education can be a tool used by individuals to move from one stratum to another in stratified societies. Higher education policies have worked to establish and reinforce stratification.[22] Greater gaps in education quality and investment in students among elite and standard universities account for the lower upward social mobility of the middle class and/or low class. Conversely, the upper class is known to be self-reproducing since they have the necessary resources and money to afford, and get into, an elite university. This class is self-reproducing because these same students can then give the same opportunities to their children.[23] Another example of this is high and middle socioeconomic status parents are able to send their children to an early education program, enhancing their chances at academic success in the later years.[6]

Housing

[edit]Mixed housing is the idea that people of different socioeconomic statuses can live in one area. There is not a lot of research on the effects of mixed housing. However, the general consensus is that mixed housing will allow individuals of low socioeconomic status to acquire the necessary resources and social connections to move up the social ladder.[24] Other possible effects mixed housing can bring are positive behavioral changes and improved sanitation and safer living conditions for the low socioeconomic status residents. This is because higher socioeconomic status individuals are more likely to demand higher quality residencies, schools, and infrastructure. This type of housing is funded by profit, nonprofit and public organizations.[25]

The existing research on mixed housing, however, shows that mixed housing does not promote or facilitate upward social mobility.[24] Instead of developing complex relationships among each other, mixed housing residents of different socioeconomic statuses tend to engage in casual conversations and keep to themselves. If noticed and unaddressed for a long period of time, this can lead to the gentrification of a community.[24]

Outside of mixed housing, individuals with a low socioeconomic status consider relationships to be more salient than the type of neighborhood they live to their prospects of moving up the social ladder. This is because their income is often not enough to cover their monthly expenses including rent. The strong relationships they have with others offers the support system they need in order for them to meet their monthly expenses. At times, low income families might decide to double up in a single residency to lessen the financial burden on each family. However, this type of support system, that low socioeconomic status individuals have, is still not enough to promote upward relative mobility.[26]

Income

[edit]

Economic and social mobility are two separate entities. Economic mobility is used primarily by economists to evaluate income mobility. Conversely, social mobility is used by sociologists to evaluate primarily class mobility. How strongly economic and social mobility are related depends on the strength of the intergenerational relationship between class and income of parents and kids, and "the covariance between parents' and children's class position".[28]

Economic and social mobility can also be thought of as following the Great Gatsby curve. This curve demonstrates that high levels of economic inequality fosters low rates of relative social mobility. The culprit behind this model is the Economic Despair idea, which states that as the gap between the bottom and middle of income distribution increases, those who are at the bottom are less likely to invest in their human capital, as they lose faith in their ability and fair chance to experience upward mobility. An example of this is seen in education, particularly in high school drop-outs. Low income status students who no longer see value in investing in their education, after continuously failing to upgrade their social status.

Race

[edit]Race as an influencer on social mobility stems from colonial times.[29] There has been discussion as to whether race can still hinder an individual's chances at upward mobility or whether class has a greater influence. A study performed on the Brazilian population found that racial inequality was only present for those who did not belong to the high-class status. Meaning race affects an individual's chances at upward mobility if they do not begin at the upper-class population. Another theory concerning race and mobility is, as time progresses, racial inequality will be replaced by class inequality.[29] However, other research has found that minorities, particularly African Americans, are still being policed and observed more at their jobs than their white counterparts. The constant policing has often led to the frequent firing of African Americans. In this case, African Americans experience racial inequality that stunts their upward social mobility.[30]

Gender

[edit]A 2019 Indian study found that Indian women, in comparison to men, experience less social mobility. One possible reason for this is the poor quality or lack of education that females receive.[31] In countries like India it is common for educated women not use their education to move up the social ladder due to cultural and traditional customs. They are expected to become homemakers and leave the bread winning to the men.[32]

A 2017 study of Indian women found that women are denied an education, as their families may find it more economically beneficial to invest in the education and wellbeing of their males instead of their females. In the parent's eyes the son will be the one who provides for them in their old age while the daughter will move away with her husband. The son will bring an income while the daughter might require a dowry to get married.[32]

When women enter the workforce, they are highly unlikely to earn the same pay as their male counterparts. Women can even differ in pay among each other due to race.[33] To combat these gender disparities, the UN has made it one of their goals on the Millennium Development Goals reduce gender inequality. This goal is accused of being too broad and having no action plan.[34]

Patterns of mobility

[edit]

While it is generally accepted that some level of mobility in society is desirable, there is no consensus agreement upon "how much" social mobility is good for or bad for a society. There is no international benchmark of social mobility, though one can compare measures of mobility across regions or countries or within a given area over time.[36] While cross-cultural studies comparing differing types of economies are possible, comparing economies of similar type usually yields more comparable data. Such comparisons typically look at intergenerational mobility, examining the extent to which children born into different families have different life chances and outcomes.

In a 2009 study, The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better, Wilkinson and Pickett conducted an exhaustive analysis of social mobility in developed countries.[35] In addition to other correlations with negative social outcomes for societies having high inequality, they found a relationship between high social inequality and low social mobility. Of the eight countries studied—Canada, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Germany, the UK and the US, the US had both the highest economic inequality and lowest economic mobility. In this and other studies, the US had very low mobility at the lowest rungs of the socioeconomic ladder, with mobility increasing slightly as one goes up the ladder. At the top rung of the ladder, mobility again decreases.[38]

A 2006 study comparing social mobility between developed countries[39][40][41] found that the four countries with the lowest "intergenerational income elasticity", i.e. the highest social mobility, were Denmark, Norway, Finland and Canada with less than 20% of advantages of having a high income parent passed on to their children.[40]

A 2012 study found "a clear negative relationship" between income inequality and intergenerational mobility.[42] Countries with low levels of inequality such as Denmark, Norway and Finland had some of the greatest mobility, while the two countries with the high level of inequality—Chile and Brazil—had some of the lowest mobility.

In Britain, much debate on social mobility has been generated by comparisons of the 1958 National Child Development Study (NCDS) and the 1970 Birth Cohort Study BCS70,[43] which compare intergenerational mobility in earnings between the 1958 and the 1970 UK cohorts, and claim that intergenerational mobility decreased substantially in this 12-year period. These findings have been controversial, partly due to conflicting findings on social class mobility using the same datasets,[44] and partly due to questions regarding the analytical sample and the treatment of missing data.[45] UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown has famously said that trends in social mobility "are not as we would have liked".[46]

Along with the aforementioned "Do Poor Children Become Poor Adults?" study, The Economist also stated that "evidence from social scientists suggests that American society is much 'stickier' than most Americans assume. Some researchers claim that social mobility is actually declining."[47][48] A 2006 German study corroborates these results.[49]

In spite of this low social mobility, in 2008, Americans had the highest belief in meritocracy among middle- and high-income countries.[50] A 2014 study of social mobility among the French corporate class found that social class influences who reaches the top in France, with those from the upper-middle classes tending to dominate, despite a longstanding emphasis on meritocracy.[51]

In 2014, Thomas Piketty found that wealth-income ratios seem to be returning to very high levels in low economic growth countries, similar to what he calls the "classic patrimonial" wealth-based societies of the 19th century, where a minority lives off its wealth while the rest of the population works for subsistence living.[52]

Social mobility can also be influenced by differences that exist within education. The contribution of education to social mobility often gets neglected in social mobility research, although it really has the potential to transform the relationship between people's social origins and destinations.[53] Recognizing the disparities between strictly location and its educational opportunities highlights how patterns of educational mobility are influencing the capacity for individuals to experience social mobility. There is some debate regarding how important educational attainment is for social mobility. A substantial literature argues that there is a direct effect of social origins (DESO) which cannot be explained by educational attainment.[54]

Other evidence suggests that, using a sufficiently fine-grained measure of educational attainment, taking on board such factors as university status and field of study, education fully mediates the link between social origins and access to top class jobs.[55]

In the US, the patterns of educational mobility that exist between inner-city schools versus schools in the suburbs is transparent. Graduation rates supply a rich context to these patterns. In the 2013–14 school year, Detroit Public Schools had a graduation rate of 71%. Grosse Pointe High School, a whiter Detroit suburb, had an average graduation rate of 94%.[56]

In 2017, a similar phenomena was observed in Los Angeles, California as well as in New York City. Los Angeles Senior High School (inner city) observed a graduation rate of 58% and San Marino High School (suburb) observed a graduation rate of 96%.[57] New York City Geographic District Number Two (inner city) observed a graduation rate of 69% and Westchester School District (suburb) observed a graduation rate of 85%.[58] These patterns were observed across the country when assessing the differences between inner city graduation rates and suburban graduation rates.

The economic grievance thesis argues that economic factors, such as deindustrialisation, economic liberalisation, and deregulation, are causing the formation of a 'left-behind' precariat with low job security, high inequality, and wage stagnation, who then support populism.[59][60] Some theories only focus on the effect of economic crises,[61] or inequality.[62] Another objection for economic reasons is due to the globalization that is taking place in the world today. In addition to criticism of the widening inequality caused by the elite, the widening inequality among the general public caused by the influx of immigrants and other factors due to globalization is also a target of populist criticism.

The evidence of increasing economic disparity and volatility of family incomes is clear, particularly in the United States, as shown by the work of Thomas Piketty and others.[63][64][65] Commentators such as Martin Wolf emphasize the importance of economics.[66] They warn that such trends increase resentment and make people susceptible to populist rhetoric. Evidence for this is mixed. At the macro level, political scientists report that xenophobia, anti-immigrant ideas, and resentment towards out-groups tend to be higher during difficult economic times.[63][67] Economic crises have been associated with gains by far-right political parties.[68][69] However, there is little evidence at the micro- or individual level to link individual economic grievances and populist support.[63][59] Populist politicians tend to put pressure on central bank independence.[70]

Influence of intelligence and education

[edit]Social status attainment and therefore social mobility in adulthood are of interest to psychologists, sociologists, political scientists, economists, epidemiologists and many more. The reason behind the interest is because it indicates access to material goods, educational opportunities, healthy environments, and economic growth.[71][72][73][74][75][76]

In Scotland, a long range study examined individuals in childhood and mid-adulthood. Most Scottish children born in 1921 participated in the Scottish Mental Survey 1932, conducted by the Scottish Council for Research in Education (SCRE)[77] It obtained the data of psychometric intelligence of Scottish pupils. The number of children who took the mental ability test (based on the Moray House tests) was 87,498. They were between age 10 and 11. The tests covered general, spatial and numerical reasoning.[71][72]

At midlife period, a subset of the subjects participated in one of the studies, which were large health studies of adults and were carried out in Scotland in the 1960s and 1970s.[71] The particular study they took part in was the collaborative study of 6022 men and 1006 women, conducted between 1970 and 1973 in Scotland. Participants completed a questionnaire (participant's address, father's occupation, the participant's own first regular occupation, the age of finishing full-time education, number of siblings, and if the participant was a regular car driver) and attended a physical examination (measurement of height). Social class was coded according to the Registrar General's Classification for the participant's occupation at the time of screening, his first occupation and his father's occupation. Researchers separated into six social classes were used.[78]

A correlation and structural equation model analysis was conducted.[71] In the structural equation models, social status in the 1970s was the main outcome variable. The main contributors to education (and first social class) were father's social class and IQ at age 11, which was also found in a Scandinavian study.[79] This effect was direct and also mediated via education and the participant's first job.[71]

Participants at midlife did not necessarily end up in the same social class as their fathers.[71] There was social mobility in the sample: 45% of men were upwardly mobile, 14% were downward mobile and 41% were socially stable. IQ at age 11 had a graded relationship with participant's social class. The same effect was seen for father's occupation. Men at midlife social class I and II (the highest, more professional) also had the highest IQ at age 11.

Height at midlife, years of education and childhood IQ were significantly positively related to upward social mobility, while number of siblings had no significant effect. For each standard deviation increase in IQ score at the age 11, the chances of upward social mobility increases by 69% (with a 95% confidence). After controlling the effect of independent variables, only IQ at age 11 was significantly inversely related to downward movement in social mobility. More years of education increase the chance that a father's son will surpass his social class, whereas low IQ makes a father's son prone to falling behind his father's social class.

Higher IQ at age 11 was also significantly related to higher social class at midlife, higher likelihood car driving at midlife, higher first social class, higher father's social class, fewer siblings, higher age of education, being taller and living in a less deprived neighbourhood at midlife.[71] IQ was significantly more strongly related to the social class in midlife than the social class of the first job.

Height, education and IQ at age 11 were predictors of upward social mobility and only IQ at age 11 and height were significant predictors of downward social mobility.[71] Number of siblings was not significant in either of the models.

Another research[73] looked into the pivotal role of education in association between ability and social class attainment through three generations (fathers, participants and offspring) using the SMS1932[72] (Lothian Birth Cohort 1921) educational data, childhood ability and late life intellectual function data. It was proposed that social class of origin acts as a ballast[73] restraining otherwise meritocratic social class movement, and that education is the primary means through which social class movement is both restrained and facilitated—therefore acting in a pivotal role.

It was found that social class of origin predicts educational attainment in both the participant's and offspring generations.[73] Father's social class and participant's social class held the same importance in predicting offspring educational attainment—effect across two generations. Educational attainment mediated the association of social class attainments across generations (father's and participants social class, participant's and offspring's social class). There was no direct link between social classes across generations, but in each generation educational attainment was a predictor of social class, which is consistent with other studies.[80][81]

Participant's childhood ability moderately predicted their educational and social class attainment (.31 and .38). Participant's educational attainment was strongly linked with the odds of moving downward or upward on the social class ladder. For each SD increase in education, the odds of moving upward on the social class spectrum were 2.58 times greater. The downward ones were .26 times greater. Offspring's educational attainment was also strongly linked with the odds of moving upward or downward on the social class ladder. For each SD increase in education, the odds of moving upward were 3.54 times greater. The downward ones were .40 times greater. In conclusion, education is very important, because it is the fundamental mechanism functioning both to hold individuals in their social class of origin and to make it possible for their movement upward or downward on the social class ladder.[73]

In the Cohort 1936 it was found that regarding whole generations (not individuals)[74] the social mobility between father's and participant's generation is: 50.7% of the participant generation have moved upward in relation to their fathers, 22.1% had moved downwards, and 27.2% had remained stable in their social class. There was a lack of social mobility in the offspring generation as a whole. However, there was definitely individual offspring movement on the social class ladder: 31.4% had higher social class attainment than their participant parents (grandparents), 33.7% moved downward, and 33.9% stayed stable. Participant's childhood mental ability was linked to social class in all three generations. A very important pattern has also been confirmed: average years of education increased with social class and IQ.

There were some great contributors to social class attainment and social class mobility in the twentieth century: Both social class attainment and social mobility are influenced by pre-existing levels of mental ability,[74] which was in consistence with other studies.[80][82][83][84] So, the role of individual level mental ability in pursuit of educational attainment—professional positions require specific educational credentials. Educational attainment contributes to social class attainment through the contribution of mental ability to educational attainment. Mental ability can contribute to social class attainment independent of actual educational attainment, as in when the educational attainment is prevented, individuals with higher mental ability manage to make use of the mental ability to work their way up on the social ladder.[84]

This study made clear that intergenerational transmission of educational attainment is one of the key ways in which social class was maintained within family, and there was also evidence that education attainment was increasing over time. Finally, the results suggest that social mobility (moving upward and downward) has increased in recent years in Britain. Which according to one researcher is important because an overall mobility of about 22% is needed to keep the distribution of intelligence relatively constant from one generation to the other within each occupational category.[84]

In 2010, researchers looked into the effects elitist and non-elitist education systems have on social mobility. Education policies are often critiqued based on their impact on a single generation, but it is important to look at education policies and the effects they have on social mobility. In the research, elitist schools are defined as schools that focus on providing its best students with the tools to succeed, whereas an egalitarian school is one that predicates itself on giving equal opportunity to all its students to achieve academic success.[85] When private education supplements were not considered, it was found that the greatest amount of social mobility was derived from a system with the least elitist public education system. It was also discovered that the system with the most elitist policies produced the greatest amount of utilitarian welfare. Logically, social mobility decreases with more elitist education systems and utilitarian welfare decreases with less elitist public education policies.[85]

When private education supplements are introduced, it becomes clear that some elitist policies promote some social mobility and that an egalitarian system is the most successful at creating the maximum amount of welfare. These discoveries were justified from the reasoning that elitist education systems discourage skilled workers from supplementing their children's educations with private expenditures.[85]

The authors of the report showed that they can challenge conventional beliefs that elitist and regressive educational policy is the ideal system. This is explained as the researchers found that education has multiple benefits. It brings more productivity and has a value, which was a new thought for education. This shows that the arguments for the regressive model should not be without qualifications. Furthermore, in the elitist system, the effect of earnings distribution on growth is negatively impacted due to the polarizing social class structure with individuals at the top with all the capital and individuals at the bottom with nothing.[85]

Education is very important in determining the outcome of one's future. It is almost impossible to achieve upward mobility without education. Education is frequently seen as a strong driver of social mobility.[86] The quality of one's education varies depending on the social class that they are in. The higher the family income the better opportunities one is given to get a good education. The inequality in education makes it harder for low-income families to achieve social mobility. Research has indicated that inequality is connected to the deficiency of social mobility. In a period of growing inequality and low social mobility, fixing the quality of and access to education has the possibility to increase equality of opportunity for all Americans.[87]

"One significant consequence of growing income inequality is that, by historical standards, high-income households are spending much more on their children's education than low-income households."[87] With the lack of total income, low-income families cannot afford to spend money on their children's education. Research has shown that over the past few years, families with high income has increased their spending on their children's education. High income families were paying $3,500 per year and now it has increased up to nearly $9,000, which is seven times more than what low income families pay for their kids' education.[87] The increase in money spent on education has caused an increase in college graduation rates for the families with high income. The increase in graduation rates is causing an even bigger gap between high income children and low-income children. Given the significance of a college degree in today's labor market, rising differences in college completion signify rising differences in outcomes in the future.[87]

Family income is one of the most important factors in determining the mental ability (intelligence) of their children. With such bad education that urban schools are offering, parents of high income are moving out of these areas to give their children a better opportunity to succeed. As urban school systems worsen, high income families move to rich suburbs because that is where they feel better education is; if they do stay in the city, they often enroll their children in private schools.[88] Low income families do not have a choice but to settle for the bad education because they cannot afford to relocate to rich suburbs. The more money and time parents invest in their child plays a huge role in determining their success in school. Research has shown that higher mobility levels are perceived for locations where there are better schools.[88]

See also

[edit]- Ascriptive inequality

- Asset poverty

- Cycle of poverty

- Desert (philosophy)

- Distribution of wealth

- Essential facilities doctrine

- Global Social Mobility Index

- Higher education bubble in the United States

- Kitchen sink realism

- Horizontal mobility

- Merit, excellence, and intelligence (MEI) – framework that emphasizes selecting candidates based solely on their merit, achievements, skills, abilities, intelligence and contributions

- Occupational prestige

- One-upmanship

- Rational expectations

- Social and Cultural Mobility

- Social stigma

- Socio-economic mobility in the United States

- Spatial inequality

- Winner and loser culture

References

[edit]- ^ a b "A Family Affair". Economic Policy Reforms 2010. 2010. pp. 181–198. doi:10.1787/growth-2010-38-en. ISBN 9789264079960.

- ^ Heckman JJ, Mosso S (August 2014). "The Economics of Human Development and Social Mobility" (PDF). Annual Review of Economics. 6: 689–733. doi:10.1146/annurev-economics-080213-040753. PMC 4204337. PMID 25346785. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Grusky DB, Cumberworth E (February 2010). "A National Protocol for Measuring Intergenerational Mobility" (PDF). Workshop on Advancing Social Science Theory: The Importance of Common Metrics. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Science. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Lopreato J, Hazelrigg LE (December 1970). "Intragenerational versus Intergenerational Mobility in Relation to Sociopolitical Attitudes". Social Forces. 49 (2): 200–210. doi:10.2307/2576520. JSTOR 2576520.

- ^ Causa O, Johansson Å (July 2009). "Intergenerational Social Mobility Economics Department Working Papers No. 707". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ a b "A Broken Social Elevator? How to Promote Social Mobility - en - OECD". www.oecd.org. 15 June 2018. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ Grusky DB, Hauser RM (February 1984). "Comparative Social Mobility Revisited: Models of Convergence and Divergence in 16 Countries". American Sociological Review. 49 (1): 19–38. doi:10.2307/2095555. JSTOR 2095555.

- ^ Weber M (1946). "Class, Status, Party". In H. H. Girth, C. Wright Mills (eds.). From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology. New York: Oxford University. pp. 180–95.

- ^ Collins, Patricia Hill (1998). "Toward a new vision: race, class and gender as categories of analysis and connection". Social Class and Stratification: Classic Statements and Theoretical Debates. Boston: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 231–247. ISBN 978-0-8476-8542-4.

- ^ a b c d Greenstone M, Looney A, Patashnik J, Yu M (18 November 2016). "Thirteen Economic Facts about Social Mobility and the Role of Education". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 8 April 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ Lareau, Annette (2011). Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life. University of California Press.

- ^ a b c Haveman R, Smeeding T (1 January 2006). "The role of higher education in social mobility". The Future of Children. 16 (2): 125–50. doi:10.1353/foc.2006.0015. JSTOR 3844794. PMID 17036549. S2CID 22554922.

- ^ a b Bourdieu, Pierre (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-56788-6.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Lareau, Annette (2003). Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life. University of California Press.

- ^ Bowen W, Bok D (20 April 2016). The Shape of the River : Long-Term Consequences of Considering Race in College and University Admissions. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400882793.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Massey D, Charles C, Lundy G, Fischer M (27 June 2011). The Source of the River: The Social Origins of Freshmen at America's Selective Colleges and Universities. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1400840762.

- ^ Becker, Gary (1964). Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Kosteniuk JG, Dickinson HD (July 2003). "Tracing the social gradient in the health of Canadians: primary and secondary determinants". Social Science & Medicine. 57 (2): 263–76. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00345-3. PMID 12765707.

- ^ Dahl E (August 1996). "Social mobility and health: cause or effect?". BMJ. 313 (7055): 435–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.313.7055.435. PMC 2351864. PMID 8776298.

- ^ Warren JR (1 June 2009). "Socioeconomic Status and Health across the Life Course: A Test of the Social Causation and Health Selection Hypotheses". Social Forces. 87 (4): 2125–2153. doi:10.1353/sof.0.0219. PMC 3626501. PMID 23596343.

- ^ Kröger H, Pakpahan E, Hoffmann R (December 2015). "What causes health inequality? A systematic review on the relative importance of social causation and health selection". European Journal of Public Health. 25 (6): 951–60. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckv111. PMID 26089181. Archived from the original on 3 June 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- ^ Neelsen, John P. (1975). "Education and Social Mobility". Comparative Education Review. 19 (1): 129–143. doi:10.1086/445813. JSTOR 1187731. S2CID 144855073.

- ^ Brezis ES, Hellier J (December 2016). "Social Mobility and Higher-Education Policy". Working Papers. Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ a b c Durova AO (2013). Does Mixed-Income Housing Facilitate Upward Social Mobility of Low-Income Residents? The Case of Vineyard Estates, Phoenix, AZ. ASU Electronic Theses and Dissertations (Masters thesis). Arizona State University. hdl:2286/R.I.18092.

- ^ "Mixed-Income Housing: Unanswered Questions". Community-Wealth.org. 30 May 2017. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ Skobba K, Goetz EG (8 October 2014). "Doubling up and the erosion of social capital among very low income households". International Journal of Housing Policy. 15 (2): 127–147. doi:10.1080/14616718.2014.961753. ISSN 1949-1247. S2CID 154912878.

- ^ a b Data from Chetty, Raj; Jackson, Matthew O.; Kuchler, Theresa; Stroebel, Johannes; et al. (1 August 2022). "Social capital I: measurement and associations with economic mobility". Nature. 608 (7921): 108–121. Bibcode:2022Natur.608..108C. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04996-4. PMC 9352590. PMID 35915342. Charted in Leonhardt, David (1 August 2022). "'Friending Bias' / A large new study offers clues about how lower-income children can rise up the economic ladder". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 August 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Breen R, Mood C, Jonsson JO (2015). "How much scope for a mobility paradox? The relationship between social and income mobility in Sweden". Sociological Science. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ a b Ribeiro CA (2007). "Class, race, and social mobility in Brazil". Dados. 3 (SE): 0. doi:10.1590/S0011-52582007000100008. ISSN 0011-5258.

- ^ "Quick Read Synopsis: Race, Ethnicity, and Inequality in the U.S. Labor Market: Critical Issues in the New Millennium". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 609: 233–248. 2007. doi:10.1177/0002716206297018. JSTOR 25097883. S2CID 220836882.

- ^ "MANY FACES OF GENDER INEQUALITY". frontline.thehindu.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ a b Rosenblum, Daniel (2 January 2017). "Estimating the Private Economic Benefits of Sons Versus Daughters in India". Feminist Economics. 23 (1): 77–107. doi:10.1080/13545701.2016.1195004. ISSN 1354-5701. S2CID 156163393.

- ^ "The Simple Truth about the Gender Pay Gap". AAUW: Empowering Women Since 1881. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ "Millennium Development Goals Report 2015". 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Wilkinson R, Pickett K (2009). The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger. Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1608190362.[page needed]

- ^ Causa O, Johansson Å (2011). "Intergenerational Social Mobility in OECD Countries". Economic Studies. 2010 (1): 1. doi:10.1787/eco_studies-2010-5km33scz5rjj. S2CID 7088564.

- ^ Corak, Miles (August 2013). "Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 27 (3): 79–102. doi:10.1257/jep.27.3.79. hdl:10419/80702.

- ^ Isaacs JB (2008). International Comparisons of Economic Mobility (PDF). Brookings Institution. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2014.

- ^ CAP: Understanding Mobility in America Archived 14 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine – 26 April 2006

- ^ a b Corak, Miles (2006). "Do Poor Children Become Poor Adults? Lessons from a Cross Country Comparison of Generational Earnings Mobility" (PDF). In Creedy, John; Kalb, Guyonne (eds.). Dynamics of Inequality and Poverty. Research on Economic Inequality. Vol. 13. Emerald. pp. 143–188. ISBN 978-0-76231-350-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Financial Security and Mobility - Pew Trusts" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ The Great Gatsby Curve Archived 7 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine Paul Krugman| 15 January 2012

- ^ Blanden J, Machin S, Goodman A, Gregg P (2004). "Changes in intergenerational mobility in Britain". In Corak M (ed.). Generational Income Mobility in North America and Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82760-7.[page needed]

- ^ Goldthorpe JH, Jackson M (December 2007). "Intergenerational class mobility in contemporary Britain: political concerns and empirical findings". The British Journal of Sociology. 58 (4): 525–46. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00165.x. PMID 18076385.

- ^ Gorard, Stephen (2008). "A reconsideration of rates of 'social mobility' in Britain: or why research impact is not always a good thing" (PDF). British Journal of Sociology of Education. 29 (3): 317–324. doi:10.1080/01425690801966402. S2CID 51853936. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Clark, Tom (10 March 2010). "Is social mobility dead?". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ "Ever higher society, ever harder to ascend". The Economist. 29 December 2004. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ Mitnik P, Cumberworth E, Grusky D (2016). "Social Mobility in a High Inequality Regime". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 66 (1): 140–183. doi:10.1177/0002716215596971. S2CID 156569226.

- ^ Jäntti M, Bratsberg B, Roed K, Rauum O, et al. (2006). "American Exceptionalism in a New Light: A Comparison of Intergenerational Earnings Mobility in the Nordic Countries, the United Kingdom and the United States". IZA Discussion Paper No. 1938.

- ^ Isaacs J, Sawhill I (2008). "Reaching for the Prize: The Limits on Economic Mobility". The Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ Maclean M, Harvey C, Kling G (1 June 2014). "Pathways to Power: Class, Hyper-Agency and the French Corporate Elite" (PDF). Organization Studies. 35 (6): 825–855. doi:10.1177/0170840613509919. S2CID 145716192. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Piketty T (2014). Capital in the 21st century. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0674430006.

- ^ Brown P, Reay D, Vincent C (2013). "Education and social mobility". British Journal of Sociology of Education. 34 (5–6): 637–643. doi:10.1080/01425692.2013.826414. S2CID 143584008.

- ^ Education, occupation and social origin : a comparative analysis of the transmission. Bernardi, Fabrizio,, Ballarino, Gabriele. Cheltenham, UK. 12 February 2024. ISBN 9781785360442. OCLC 947837575.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Sullivan A, Parsons S, Green F, Wiggins RD, Ploubidis G (September 2018). "The path from social origins to top jobs: social reproduction via education" (PDF). The British Journal of Sociology. 69 (3): 776–798. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12314. PMID 28972272. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 July 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "DPS Graduation rates are up 6.5 percentage points over last year and 11 percentage points since 2010–11". 6 March 2015. Archived from the original on 8 April 2017.

- ^ "Overall Niche Grade". Archived from the original on 8 April 2017.

- ^ "WESTCHESTER COUNTY GRADUATION RATE DATA 4 YEAR OUTCOME AS OF JUNE". Archived from the original on 8 April 2017.

- ^ a b Norris, Pippa; Inglehart, Ronald (11 February 2019). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 134–139. doi:10.1017/9781108595841. ISBN 978-1-108-59584-1. S2CID 242313055.

- ^ Broz, J. Lawrence; Frieden, Jeffry; Weymouth, Stephen (2021). "Populism in Place: The Economic Geography of the Globalization Backlash". International Organization. 75 (2): 464–494. doi:10.1017/S0020818320000314. ISSN 0020-8183.

- ^ Mudde, Cas (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 205–206. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511492037. ISBN 978-0-511-49203-7.

- ^ Flaherty, Thomas M.; Rogowski, Ronald (2021). "Rising Inequality As a Threat to the Liberal International Order". International Organization. 75 (2): 495–523. doi:10.1017/S0020818321000163. ISSN 0020-8183.

- ^ a b c Berman, Sheri (11 May 2021). "The Causes of Populism in the West". Annual Review of Political Science. 24 (1): 71–88. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102503.

- ^ Piketty, Thomas (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambridge Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-43000-6.

- ^ Hacker, Jacob S. (2019). The great risk shift: the new economic insecurity and the decline of the American dream (Expanded & fully revised second ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-084414-1.

- ^ Wolf, M. (3 December 2019). "How to reform today's rigged capitalism". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ Dancygier, RM. (2010). Immigration and Conflict in Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Klapsis, Antonis (December 2014). "Economic Crisis and Political Extremism in Europe: From the 1930s to the Present". European View. 13 (2): 189–198. doi:10.1007/s12290-014-0315-5.

- ^ Funke, Manuel; Schularick, Moritz; Trebesch, Christoph (September 2016). "Going to extremes: Politics after financial crises, 1870–2014" (PDF). European Economic Review. 88: 227–260. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2016.03.006. S2CID 154426984. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 July 2023. Retrieved 26 November 2023.

- ^ Gavin, Michael; Manger, Mark (2023). "Populism and de Facto Central Bank Independence". Comparative Political Studies. 56 (8): 1189–1223. doi:10.1177/00104140221139513. PMC 10251451. PMID 37305061.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Deary IJ, Taylor MD, Hart CL, Wilson V, Smith GD, Blane D, Starr JM (September 2005). "Intergenerational social mobility and mid-life status attainment: Influences of childhood intelligence, childhood social factors, and education" (PDF). Intelligence. 33 (5): 455–472. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2005.06.003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ a b c Deary IJ, Whiteman MC, Starr JM, Whalley LJ, Fox HC (January 2004). "The impact of childhood intelligence on later life: following up the Scottish mental surveys of 1932 and 1947". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 86 (1): 130–47. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.130. PMID 14717632.

- ^ a b c d e Johnson W, Brett CE, Deary IJ (January 2010). "The pivotal role of education in the association between ability and social class attainment: A look across three generations". Intelligence. 38 (1): 55–65. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2009.11.008.

- ^ a b c Johnson W, Brett CE, Deary IJ (March 2010). "Intergenerational class mobility in Britain: A comparative look across three generations in the Lothian birth cohort 1936" (PDF). Intelligence. 38 (2): 268–81. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2009.11.010. hdl:20.500.11820/c1a4facd-67f3-484b-8943-03f62e5babc0. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Breen R, Goldthorpe JH (June 2001). "Class, mobility and merit the experience of two British birth cohorts". European Sociological Review. 17 (2): 81–101. doi:10.1093/esr/17.2.81.

- ^ Von Stumm S, Gale CR, Batty GD, Deary IJ (July 2009). "Childhood intelligence, locus of control and behaviour disturbance as determinants of intergenerational social mobility: British Cohort Study 1970". Intelligence. 37 (4): 329–40. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2009.04.002.

- ^ Scottish Council for Research in Education (1933). The intelligence of Scottish children: A national survey of an age-group. London, UK7 University of London Press.

- ^ General Register Office (1966). Classification of occupations 1966. London, UK7 HMSO.

- ^ Sorjonen, K., Hemmingsson, T., Lundin, A., & Melin, B. (2011). How social position of origin relates to intelligence and level of education when adjusting for attained social position[dead link]. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 277–281.

- ^ a b Nettle D (November 2003). "Intelligence and class mobility in the British population". British Journal of Psychology. 94 (Pt 4): 551–61. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.482.4805. doi:10.1348/000712603322503097. PMID 14687461.

- ^ Forrest LF, Hodgson S, Parker L, Pearce MS (November 2011). "The influence of childhood IQ and education on social mobility in the Newcastle Thousand Families birth cohort". BMC Public Health. 11 895. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-895. PMC 3248886. PMID 22117779.

- ^ Waller JH (September 1971). "Achievement and social mobility: relationships among IQ score, education, and occupation in two generations". Social Biology. 18 (3): 252–9. doi:10.1080/19485565.1971.9987927. PMID 5120877.

- ^ Young M, Gibson J (1963). "In search of an explanation of social mobility". The British Journal of Statistical Psychology. 16 (1): 27–36. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8317.1963.tb00196.x.

- ^ a b c Burt C (May 1961). "Intelligence and social mobility". British Journal of Statistical Psychology. 14 (1): 3–24. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8317.1961.tb00062.x.

- ^ a b c d Cremer H, De Donder P, Pestieau P (1 August 2010). "Education and social mobility" (PDF). International Tax and Public Finance. 17 (4): 357–377. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.637.2983. doi:10.1007/s10797-010-9133-0. ISSN 0927-5940. S2CID 6848305. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 July 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ "Social Mobility and Education | The Equality Trust". www.equalitytrust.org.uk. Archived from the original on 8 April 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Thirteen Economic Facts about Social Mobility and the Role of Education | Brookings Institution". Brookings. 26 June 2013. Archived from the original on 8 April 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ a b Herrnstein R (1994). The Bell Curve: intelligence and Class Structure in American Life. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-02-914673-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Clark G (2014). The Son Also Rises: Surnames and the History of Social Mobility. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Grusky, David B; Cumberworth, Erin (2012). A National Protocol for Measuring Intergenerational Mobility? (PDF). National Academy of Science. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- Lipset, Seymour Martin; Bendix, Reinhard (1991). Social Mobility in Industrial Society. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9781412834353.

- Matthys M (2012). Cultural Capital, Identity, and Social Mobility. Routledge.

- Maume, David J. (19 August 2016). "Glass Ceilings and Glass Escalators". Work and Occupations. 26 (4): 483–509. doi:10.1177/0730888499026004005. S2CID 145308055.

- McGuire GM (2000). "Gender, Race, Ethnicity, and Networks: The Factors Affecting the Status of Employees' Network Members". Work and Occupations. 27 (4): 500–523. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.979.3395. doi:10.1177/0730888400027004004. S2CID 145264871.

- Mitnik PA, Cumberworth E, Grusky DB (January 2016). "Social mobility in a high-inequality regime". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 663 (1): 140–84. doi:10.1177/0002716215596971. S2CID 156569226.

External links

[edit]- Birdsall N, Szekely M (July 1999). "Intergenerational Mobility in Latin America: Deeper Markets and Better Schools Make a Difference". Carnegie. Archived from the original on 21 October 2005.

- The New York Times offers a graphic about social mobility, overall trends, income elasticity and country by country. European nations such as Denmark and France, are ahead of the US. [1]

Social mobility

View on GrokipediaConceptual Foundations

Definitions and Distinctions

Social mobility denotes the capacity of individuals, families, or groups to alter their socioeconomic position within a society's stratification system, typically measured by changes in income, occupation, education, or wealth.[8] This movement can reflect broader economic growth or structural shifts, but it fundamentally involves transitions across class boundaries or status levels.[9] A primary distinction lies between absolute and relative mobility. Absolute mobility evaluates whether offspring attain higher absolute levels of socioeconomic attainment—such as greater income or educational credentials—than their parents, irrespective of peers' outcomes; for instance, widespread economic expansion post-World War II elevated many families' living standards in Western nations.[3] Relative mobility, conversely, gauges the persistence of inequality in positional rankings, focusing on the correlation between parental and child socioeconomic ranks; high relative mobility implies low intergenerational transmission of advantage or disadvantage.[10] Social mobility is further differentiated by timeframe: intergenerational mobility tracks status changes from parents to children, often using metrics like the income elasticity between generations, where a value near zero indicates strong mobility.[11] Intragenerational mobility, by contrast, assesses status shifts within a single lifetime, such as career progression from low-wage labor to managerial roles.[12] In terms of direction and nature, vertical mobility encompasses upward shifts (gains in socioeconomic standing, e.g., from working-class to professional occupations) and downward shifts (losses, such as job displacement leading to underemployment).[13] Horizontal mobility involves lateral changes without net status alteration, like transferring between equivalent roles in different firms or sectors.[14] These categories highlight that not all positional changes equate to substantive advancement, as horizontal moves may preserve rather than elevate resources or opportunities.[9]Theoretical Perspectives

Functionalist theories regard social mobility as essential for societal efficiency, arguing that unequal rewards motivate individuals to acquire skills for critical roles. In their 1945 formulation, Kingsley Davis and Wilbert E. Moore contended that stratification functions to match the most talented with positions demanding high functional importance, such as medicine or leadership, through competitive selection via education and achievement, thereby enabling upward mobility for those demonstrating merit. This perspective assumes open competition and merit-based allocation, positing that mobility reinforces social stability by fulfilling societal needs.[15] Conflict theories, influenced by Karl Marx, counter that social mobility is largely constrained by entrenched power imbalances, where dominant classes manipulate institutions to perpetuate inequality and limit access for subordinates. Proponents argue that apparent mobility serves ideological purposes, masking exploitation while elites control resources like capital and policy to hinder structural change, resulting in persistent class reproduction rather than genuine opportunity.[16] This view emphasizes antagonism over harmony, attributing low mobility rates to deliberate barriers rather than individual failings.[17] Economic theories, particularly human capital theory advanced by Gary Becker, frame social mobility as outcomes of rational investments in education, training, and health that boost productivity and wages. Becker's model, extended to intergenerational contexts, posits that parents allocate resources to children's human capital development based on expected returns, with higher investments from advantaged families yielding greater mobility persistence unless offset by public policies or market dynamics.[18] Empirical extensions highlight complementarities in skill production, where initial endowments amplify or diminish mobility prospects.[19] Additional sociological frameworks, such as Pierre Bourdieu's cultural capital theory, explain mobility limitations through non-financial assets like tastes, knowledge, and dispositions inherited via family habitus, which align with dominant institutional demands and confer unearned advantages in schooling and careers.[20] Bourdieu argued these embodied forms reproduce class hierarchies covertly, as lower-status groups lack the subtle competencies to compete equally, challenging purely meritocratic accounts by revealing hidden reproduction mechanisms.[21] Debates persist on whether such theories overstate structural determinism, given evidence of agency and innate factors influencing outcomes, though academic discourse often prioritizes environmental explanations.[22]Determinants

Biological and Cognitive Influences

General intelligence, often measured by IQ tests, exhibits high heritability, estimated at 50-80% in adulthood based on twin and adoption studies, and strongly predicts educational attainment, occupational status, and income, thereby influencing social mobility.[23] A one standard deviation increase in childhood IQ is associated with significantly higher odds of upward mobility from ages 5 to 49-51, independent of education level.[24] Intergenerational correlations in IQ are approximately 0.38, indicating partial transmission of cognitive ability across generations that contributes to status persistence or change.[25] Twin studies reveal moderate heritability for socioeconomic outcomes, with estimates for educational attainment around 40-50% and for income similarly in that range, suggesting genetic factors explain a substantial portion of variance in social mobility beyond shared environmental influences.[26] Heritability of education increases in contexts of higher intergenerational mobility, as reduced social inheritance allows genetic potentials to manifest more fully.[6] Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) further support this through polygenic scores for educational attainment, which predict 10-16% of variance in years of schooling and are linked to career success, wealth accumulation, and upward social movement, even among individuals from lower-status families.[27][28] Biological mechanisms extend beyond cognition to include gene-environment interactions, where genetic influences on cognitive development are amplified or moderated by socioeconomic context; for instance, heritability of intelligence may be higher in advantaged environments according to some analyses, though evidence is mixed with other studies finding stronger genetic effects in deprived settings.[29][30] Genes underlying cognitive traits also correlate with family socioeconomic status, driving part of the parent-offspring resemblance in outcomes via direct genetic transmission rather than solely cultural inheritance.[31] These findings underscore that while environmental factors matter, innate biological differences in cognitive capacity impose limits on equality of opportunity and contribute causally to observed mobility patterns.Familial and Cultural Factors

Parental socioeconomic status, particularly education and income levels, exerts a substantial influence on children's intergenerational mobility. Studies indicate that children of parents with higher education attainments are more likely to achieve advanced educational credentials themselves, with causal estimates showing that an additional year of parental schooling increases child educational attainment by approximately 0.1 to 0.2 years.[32] Similarly, parental income during early childhood correlates strongly with adult child earnings, where a 10% increase in family income in the first few years predicts up to a 0.5% rise in child income percentiles, though effects diminish over time.[33] These patterns persist across cohorts, with family background explaining around 15% of variance in adult income, underscoring the role of resource transmission rather than mere correlation.[34] Family structure significantly shapes mobility trajectories, with children raised in stable two-parent households demonstrating higher upward mobility and lower persistence of poverty compared to those in single-parent or disrupted families. Empirical analyses of U.S. longitudinal data reveal that individuals from intact families have 10-20% higher odds of reaching the top income quintile, attributing this to greater parental supervision, resource pooling, and stability that foster skill development.[35] [36] In contrast, single-parent households, often facing economic strain and time constraints, correlate with reduced educational attainment and earnings, with children experiencing 25-50% lower mobility rates in absolute terms.[37] This effect holds after controlling for income, suggesting causal channels beyond finances, such as role modeling and conflict resolution.[38] Cultural factors, including transmitted values and practices, mediate familial influences on mobility by shaping behaviors like persistence and educational prioritization. Research on cultural transmission shows that families emphasizing academic achievement and work ethic—measured via surveys on attitudes toward effort and delay of gratification—predict higher child outcomes, with intergenerational correlations of 0.3-0.4 in educational mobility.[39] Parental investments in cognitive stimulation, such as reading and structured activities, amplify this, yielding effect sizes comparable to income boosts in randomized interventions.[32] However, cultural capital disparities, like familiarity with institutional norms, can perpetuate advantages for higher-status families, though empirical tests reveal these operate primarily through reinforced habits rather than inherent superiority.[40] These elements interact with biology but independently contribute via environmental reinforcement, as evidenced in adoption studies where family cultural milieu overrides genetic baselines in non-cognitive skills.[41]Economic and Institutional Factors

Higher levels of income inequality are associated with reduced intergenerational economic mobility, as depicted in the Great Gatsby Curve, which plots cross-sectional inequality against persistence in relative income positions across OECD countries.[42] This relationship holds in panel data analyses spanning multiple nations and periods, where a one-standard-deviation increase in inequality correlates with heightened income persistence from parents to children.[4] Empirical studies using administrative tax records in the United States confirm that children from low-income families face persistent barriers, with only about 7.5% reaching the top income quintile if born to parents in the bottom quintile during the 1980-1990 birth cohorts.[43] Family income influences mobility through mechanisms like credit constraints for education investment; children from poorer households invest less in human capital due to borrowing limits, perpetuating inequality.[1] Rising costs of higher education exacerbate this, as tuition increases outpace wage growth, limiting access for those without familial wealth—U.S. public university tuition rose 213% from 1980 to 2020 after inflation adjustment.[44] Labor market dynamics further shape outcomes: rigid wage structures and barriers to entry-level jobs hinder low-skilled workers' advancement, while economic downturns amplify scarring effects on youth from disadvantaged backgrounds.[45] Institutionally, equitable access to quality education systems promotes mobility by equalizing skill acquisition opportunities; countries with universal early childhood education and merit-based higher education admissions show higher absolute mobility rates.[8] Labor market institutions, including flexible hiring and firing regulations, facilitate job matching and wage adjustments that benefit mobile workers, though excessive rigidity in Europe correlates with youth unemployment rates exceeding 20% in some nations as of 2023.[46] Broader institutional quality, such as rule of law and low corruption, underpins mobility by ensuring fair competition; World Bank analyses indicate that birthplace circumstances, mediated by institutional factors, explain up to 49% of income variance in developing economies.[47] Policies fostering institutional reforms, like reducing regulatory barriers to entrepreneurship, have been linked to 1-2 percentage point gains in mobility metrics in high-mobility nations like Denmark.[48]Empirical Evidence

Measurement Methods

Social mobility is quantified through absolute and relative measures, distinguishing between overall upward movement and changes in socioeconomic position relative to peers. Absolute mobility assesses the extent to which children surpass their parents' economic status, often calculated as the percentage of children whose income exceeds that of their parents, adjusted for economic growth. For instance, in the United States, absolute upward income mobility declined from 92% for children born in 1940 to 50% for those born in 1980, reflecting slower growth in living standards for later cohorts.[49] Relative mobility, conversely, evaluates persistence across generations, independent of aggregate growth, using metrics like the intergenerational elasticity (IGE) of income, which regresses children's log income on parents' log income; a value near zero indicates high mobility, while the U.S. IGE hovers around 0.4, implying moderate persistence.[2][49] Common techniques for relative mobility include the rank-rank slope, which estimates the expected percentile rank of a child given the parent's rank in the income distribution; U.S. estimates yield a slope of approximately 0.34, where a child of a parent at the 25th percentile reaches the 34th percentile on average.[2] Transition matrices tabulate probabilities of moving between socioeconomic classes, such as from low to high income quintiles, often derived from occupational prestige scales or educational attainment data.[13] Empirical studies leverage administrative data like tax records for precision in income measurement or longitudinal surveys such as the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to track families over decades, enabling robust intergenerational correlations.[50] Educational mobility is similarly gauged by parent-child correlations in years of schooling or attainment levels, with international comparisons using standardized metrics from bodies like the OECD.[51] Challenges in measurement include life-cycle bias, as income fluctuates with age, necessitating observations of adults in comparable career stages—typically ages 30-40 for children and 40-50 for parents—to mitigate attenuation.[52] Classical measurement error in self-reported surveys biases estimates downward, though administrative data reduces this issue but raises privacy concerns and limits accessibility.[52] Heterogeneous effects by gender, race, or geography complicate aggregation, as does defining the socioeconomic unit—nuclear family versus single-parent households—affecting estimates in diverse societies.[52] Intragenerational mobility, tracking individual progress over a lifetime, employs similar tools but faces greater data demands for long-term tracking.[3]| Metric | Description | Interpretation | U.S. Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Mobility | % of children exceeding parents' income | Higher % = greater upward movement | 50% for 1980 cohort[49] |

| IGE | Slope of log child income on log parent income | Lower value = higher mobility | ~0.4[2] |

| Rank-Rank Slope | Expected child rank given parent rank | Slope closer to 0 = more equality of position | 0.34[2] |