Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Distribution of wealth

View on Wikipedia

The distribution of wealth is a comparison of the wealth of various members or groups in a society. It shows one aspect of economic inequality or economic heterogeneity.

The distribution of wealth differs from the income distribution in that it looks at the economic distribution of ownership of the assets in a society, rather than the current income of members of that society. According to the International Association for Research in Income and Wealth, "the world distribution of wealth is much more unequal than that of income."[1]

For rankings regarding wealth, see List of sovereign states by wealth inequality or list of countries by wealth per adult.

Definition of wealth

[edit]Wealth of an individual is defined as net worth, expressed as: wealth = assets − liabilities

A broader definition of wealth, which is rarely used in the measurement of wealth inequality, also includes human capital. For example, the United Nations definition of inclusive wealth is a monetary measure which includes the sum of natural, human and physical assets.[2][3]

The relation between wealth, income, and expenses is: change of wealth = saving = income − consumption (expenses). If an individual has a large income but also large expenses, the net effect of that income on her or his wealth could be small or even negative.

Conceptual framework

[edit]There are many ways in which the distribution of wealth can be analyzed. One common-used example is to compare the amount of the wealth of individual at say 99 percentile relative to the wealth of the median (or 50th) percentile. This is P99/P50 is one of the potential Kuznets ratios which is the inverted U shape that indicates the relationship between the inequality and the income per capita. Another common measure is the ratio of total amount of wealth in the hand of top say 1% of the wealth distribution over the total wealth in the economy. In many societies, the richest ten percent control more than half of the total wealth.

The Pareto Distribution has often been used to mathematically quantify the distribution of wealth at the right tail (the wealth of the very rich); stating that the upper 20% owns 80%, the upper 4% owns 64%, the upper 0.8% owns 51.2%, etc. In fact, the tail of wealth distributions, similar to that of income distribution, behaves like a Pareto distribution but with a thicker tail.

Wealth over people (WOP) curves are a visually compelling way to show the distribution of wealth in a nation. WOP curves are modified distribution of wealth curves. The vertical and horizontal scales each show percentages from zero to one hundred. We imagine all the households in a nation being sorted from richest to poorest. They are then shrunk down and lined up (richest at the left) along the horizontal scale. For any particular household, its point on the curve represents how their wealth compares (as a proportion) to the average wealth of the richest percentile. For any nation, the average wealth of the richest 1/100 of households is the topmost point on the curve (people, 1%; wealth, 100%) or (p=1, w=100) or (1, 100). In the real world two points on the WOP curve are always known before any statistics are gathered. These are the topmost point (1, 100) by definition, and the rightmost point (poorest people, lowest wealth) or (p=100, w=0) or (100, 0). This unfortunate rightmost point is given because there are always at least one percent of households (incarcerated, long term illness, etc.) with no wealth at all. Given that the topmost and rightmost points are fixed ... our interest lies in the form of the WOP curve between them. There are two extreme possible forms of the curve. The first is the "perfect communist" WOP. It is a straight line from the leftmost (maximum wealth) point horizontally across the people scale to p=99. Then it drops vertically to wealth = 0 at (p=100, w=0).

The other extreme is the "perfect tyranny" form. It starts on the left at the Tyrant's maximum wealth of 100%. It then immediately drops to zero at p=2, and continues at zero horizontally across the rest of the people. That is, the tyrant and his friends (the top percentile) own all the nation's wealth. All other citizens are serfs or slaves. An obvious intermediate form is a straight line connecting the left/top point to the right/bottom point. In such a "Diagonal" society a household in the richest percentile would have just twice the wealth of a family in the median (50th) percentile. Such a society is compelling to many (especially the poor). In fact it is a comparison to a diagonal society that is the basis for the Gini values used as a measure of the disequity in a particular economy. These Gini values (40.8 in 2007) show the United States to be the third most dis-equitable economy of all the developed nations (behind Denmark and Switzerland).

More sophisticated models have also been proposed.[4]

Theoretical approaches

[edit]To model aspects of the distribution and holdings of wealth, there have been many different types of theories used. Before the 1960s, the data regarding this was collected mostly from wealth tax and estate tax records, with further proof gathered from small unrepresentative examinations and a variety of other sources. The results from these sources tended to show that the distribution of wealth was very unequal, and that material inheritance had a big role in the matter of wealth differences and in the transmission of the status of wealth from generation to generation. There was also reason to believe that the inequality in wealth was shrinking over time, and also the distribution's shape demonstrated particular statistical regularities that could not have been caused by coincidence. Thus, early theoretical work on the distribution of wealth wanted to explain the statistical regularities, and also comprehend the relationship of basic forces which could be an explanation for the concentration of wealth to be high and the trend of declining over time.[5] John Maynard Keynes explored the impact of monetary policy on wealth distribution in A Tract on Monetary Reform.[6]

More lately, the research about wealth distribution has moved away from the worry with overall distributional characteristics, and in its place focuses more on the grounds of individual differences in the holdings of wealth.[5] This change was caused partly because the importance of saving for retirement increased, and it is reflected in the vital role now assigned to the model of lifecycle savings developed by Modigliani and Brumberg[7] (1954), and Ando and Modigliani[8] (1963). Another important progress has been the increase in availability and finesse in sets of micro-data, which offer not just estimations of individuals' asset holdings and savings but also a variety of other household and personal characteristics that can assist in explain the differences in wealth.[5]

Wealth inequality

[edit]

Wealth inequality refers to uneven distribution of wealth among individuals and entities. Although most research depends on written sources, archaeologists and anthropologists often view large houses as occupied by wealthy households.[9] The distribution of contemporaneous house sizes in a society (perhaps analyzed using the Gini coefficient) then can regarded as a measure of wealth inequality. This approach has been used at least since 2014[10] and has shown, for example, that ancient wealth disparities in Eurasia were greater than those in North America and in Mesoamerica following the earliest Neolithic period.[11]

Global inequality statistics

[edit]

A study by the World Institute for Development Economics Research at United Nations University reports that the richest 1% of adults alone owned 40% of global assets in the year 2000, and that the richest 10% of adults accounted for 85% of the world total. The bottom half of the world adult population owned 1% of global wealth.[14] A 2006 study found that the richest 2% own more than half of global household assets.[15] The Pareto distribution gives 52.8% owned by the upper 1%.

According to the OECD in 2012 the top 0.6% of world population (consisting of adults with more than US$1 million in assets) or the 42 million richest people in the world held 39.3% of world wealth. The next 4.4% (311 million people) held 32.3% of world wealth. The bottom 95% held 28.4% of world wealth. The large gaps of the report get by the Gini index to 0.893, and are larger than gaps in global income inequality, measured in 2009 at 0.38.[16] For example, in 2012 the bottom 60% of the world population held the same wealth in 2012 as the people on Forbes' Richest list consisting of 1,226 richest billionaires of the world.

A 2021 Oxfam report found that collectively, the 10 richest men in the world owned more than the combined wealth of the bottom 3.1 billion people, almost half of the entire world population. Their combined wealth doubled during the pandemic.[17][18][19]

‘Global wealth Report 2021’, published by Credit Suisse, shows a substantial worldwide increase in wealth inequality during 2020. According to Credit Suisse, wealth distribution pyramid in 2020 shows that the richest group of adult population (1.1%) owns 45.8% of the total wealth. When compared to the 2013 wealth distribution pyramid, an overall increase of 4.8% can be seen. The bottom half of the world’s total adult population, the bottom quartile in the pyramid, owns only 1.3% of the total wealth. Again, when compared to the 2013 wealth distribution pyramid, a decrease of 1.7% can be observed. In conclusion, this comparison shows a substantial worldwide increase in wealth inequality over these years.

One of the main explanations for the ongoing increase of wealth inequality are the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Credit Suisse claims that the economic impact of the pandemic on employment and incomes in 2020 are likely to have a negative effect for the lowest groups of wealth holders, forcing them to spend more from their savings or incur higher debt. On the other hand, top wealth groups appeared to be relatively unaffected in this negative way. Moreover, they seemed to benefit from the impact of lower interest rates on share and house prices.[20][21]

According to the ‘Global Wealth Report 2021’ published by Credit Suisse, there are 56 million millionaires in the world in 2020, increasing by 5.2 million from a year earlier. The biggest number of dollar millionaires is reported in the USA, with 22 million millionaires (approximately 39% of the world total). This is far ahead of China, holding second place, with 9.4% of all global millionaires. The third place is currently being held by Japan, with 6.6% of all global millionaires.[20]

Real estate

[edit]While sizeable numbers of households own no land, few have no income. For example, the top 10% of land owners (all corporations) in Baltimore, Maryland own 58% of the taxable land value. The bottom 10% of those who own any land own less than 1% of the total land value.[22] This form of analysis as well as Gini coefficient analysis has been used to support land value taxation.

Wealth distribution pyramid

[edit]

In 2013, Credit Suisse prepared a wealth pyramid infographic (shown right). Personal assets were calculated in net worth, meaning wealth would be negated by having any mortgages.[13] It has a large base of low wealth holders, alongside upper tiers occupied by progressively fewer people. In 2013 Credit-suisse estimate that 3.2 billion individuals – more than two thirds of adults in the world – have wealth below US$10,000. A further one billion (adult population) fall within the 10,000 – US$100,000 range. While the average wealth holding is modest in the base and middle segments of the pyramid, their total wealth amounts to US$40 trillion, underlining the potential for novel consumer products and innovative financial services targeted at this often neglected segment.[21]

The pyramid shows that:

- half of the world's net wealth belongs to the top 1%,

- top 10% of adults hold 85%, while the bottom 90% hold the remaining 15% of the world's total wealth,

- top 30% of adults hold 97% of the total wealth.

Wealth distribution pyramid in 2020

[edit]In 2020, Credit Suisse created an updated wealth pyramid infographic. The infographic was constructed similarly to the pyramid in 2013, thus personal assets were calculated in net worth. In 2020, Credit Suisse estimated that approximately 2.88 billion people (55% of adult population) have wealth below US$10,000. Further, 1.7 billion individuals (38.2% of adult population) have wealth within the range of 10,000 – US$100,000. To continue, 583 million people have wealth within the range of 100,000 – US$1,000,000 and approximately 56 million people (1.1% of adult population) have wealth over US$1,000,000.[20]

Comparison of 2013 and 2020 pyramids

[edit]Vast differences between 2013 and 2020 infographic can be observed. For the first time, more than 1% of all global adults have wealth over US$1,000,000. Credit Suisse explains in the ‘Global Wealth Report 2021’, that this increase reflects the economic disruption caused by the pandemic and disconnect between the improvement in the financial and real assets of households. However, the biggest difference can be seen in the 10,000 – US$100,000 segment. Since 2013, there had been an increase of almost 10% of total adult population. According to Credit Suisse, the number of adults in this segment tripled since 2000. Credit Suisse explains this fact by stating that this increase was a result of growing prosperity of emerging economies, especially China, and the expansion of the middle class in the developing world. The upper-middle segment, with wealth in a range of 100,000 – US$1,000,000 has increased by 3.4%. Credit Suisse in the report states that the middle class in developed countries typically belong to this group.[20]

Wealth outlook for 2020-2025

[edit]According to the ‘Global wealth Report 2021’, published by Credit Suisse, global wealth is projected to rise by 39% over the next five years reaching USD 583 trillion by 2025. Wealth per adult is also projected to increase by 31% and so is the number of global millionaires. The wealth pyramid, an infographic used to determine wealth distribution, will also change. The bottom segment covering adults with a net worth below USD 10,000 will likely decrease by approximately 108 million over the next five years. The lower-middle segment of the pyramid containing adults with a net worth in the range of USD 10,000 and USD 100,000 is projected to rise by 237 million adults. Most of these new members are most likely to be from lower-income countries. The upper-middle segment, consisting of adults with wealth between USD 100,000 and USD 1 million is projected to rise by 178 million adults. Most of these new members (approximately 114 million) are likely to come from upper-middle-income countries. Number of global millionaires is also projected to increase. According to the estimates made by Credit Suisse, the number of global millionaires could exceed 84 million by 2025, a rise of almost 28 million from 2020. The increase of millionaires will not only occur in developed countries such as the USA or other developed countries in Europe, but it is also expected to rapidly increase in lower-income countries. The biggest increase is expected in China, with a change of 92.7%, which is about 4.8 million new dollar millionaires. As a consequence, the number of Ultra High Net Worth Individuals (UHNWI) with net worth exceeding USD 50 million, will also increase.[20]

Gini Coefficient

[edit]Gini coefficient (or Gini index) is an indicator that is often used to determine wealth inequality. A Gini coefficient of 0 reflects perfect equality, where all income or wealth values are the same, while a Gini coefficient of 1 (or 100%) reflects maximal inequality among values, a situation where a single individual has all the income while all others have none.[23] According to the Credit Suisse ‘Global wealth Report 2021’, Brunei had the highest Gini coefficient in 2021 (91.6%), therefore the wealth distribution in Brunei is vastly unequal. Slovakia had the lowest Gini coefficient in 2021 (50.3%) out of all countries, which makes Slovakia the most equal country in terms of wealth distribution. When compared to the report made by Credit Suisse in 2019, an increasing trend of wealth inequality can be observed. This may be the result of repercussions of the Covid-19 pandemic. The biggest increase was recorded in Brazil. The Gini coefficient in 2019 was 88.2% and 89% in 2021, with an increase of 0.8% over this period.[24]

The following table was created from information provided by the Credit Suisse Research Institute's "Global Wealth Databook", Table 3-1, published 2021.[24]

Click at right to show/hide table with detailed statistics

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

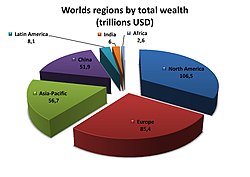

Geographical distribution

[edit]Wealth is unevenly distributed across different world regions. At the end of the 20th century, wealth was concentrated among the G8 and Western industrialized nations, along with several Asian and OPEC nations. In the 21st century, wealth is still concentrated among the G8 with United States of America leading with 30.2%, along with other developed countries, several Asia-pacific countries and OPEC countries.

-

World distribution of wealth by country (PPP)

-

World distribution of wealth by region (PPP)

-

World distribution of wealth by country (exchange rates)

-

World distribution of wealth by region (exchange rates)

By region

[edit]| Region | Proportion of world (%)[25][26] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Net worth | GDP | |||

| PPP | Exchange rates | PPP | Exchange rates | ||

| North America | 5.2 | 27.1 | 34.4 | 23.9 | 33.7 |

| Central/South America | 8.5 | 6.5 | 4.3 | 8.5 | 6.4 |

| Europe | 9.6 | 26.4 | 29.2 | 22.8 | 32.4 |

| Africa | 10.7 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 1.0 |

| Middle East | 9.9 | 5.1 | 3.1 | 5.7 | 4.1 |

| Asia | 52.2 | 29.4 | 25.6 | 31.1 | 24.1 |

| Other | 3.2 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 5.4 | 3.4 |

| Totals (rounded) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

World distribution of financial wealth. In 2007, 147 companies controlled nearly 40 percent of the monetary value of all transnational corporations.[27]

In the United States

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (October 2022) |

According to PolitiFact, in 2011 the 400 wealthiest Americans "have more wealth than half of all Americans combined."[33][34][35][36] Inherited wealth may help explain why many Americans who have become rich may have had a "substantial head start".[37][38] In September 2012, according to the Institute for Policy Studies, "over 60 percent" of the Forbes richest 400 Americans "grew up in substantial privilege".[39]

In 2007, the richest 1% of the American population owned 34.6% of the country's total wealth (excluding human capital),[clarification needed] and the next 19% owned 50.5%. The top 20% of Americans owned 85% of the country's wealth and the bottom 80% of the population owned 15%. From 1922 to 2010, the share of the top 1% varied from 19.7% to 44.2%, the big drop being associated with the drop in the stock market in the late 1970s. Ignoring the period where the stock market was depressed (1976–1980) and the period when the stock market was overvalued (1929), the share of wealth of the richest 1% remained extremely stable, at about a third of the total wealth.[25] Financial inequality was greater than inequality in total wealth, with the top 1% of the population owning 42.7%, the next 19% of Americans owning 50.3%, and the bottom 80% owning 7%.[40] However, following the Great Recession which started in 2007, the share of total wealth owned by the top 1% of the population grew from 34.6% to 37.1%, and that owned by the top 20% of Americans grew from 85% to 87.7%. The Great Recession also caused a drop of 36.1% in median household wealth but a drop of only 11.1% for the top 1%, further widening the gap between the 1% and the 99%.[41][25][40]

Dan Ariely and Michael Norton show in a study (2011) that US citizens across the political spectrum significantly underestimate the current US wealth inequality and would prefer a more egalitarian distribution of wealth, raising questions about ideological disputes over issues like taxation and welfare.[42]

| Year | Bottom 99% |

Top 1% |

|---|---|---|

| 1922 | 63.3% | 36.7% |

| 1929 | 55.8% | 44.2% |

| 1933 | 66.7% | 33.3% |

| 1939 | 63.6% | 36.4% |

| 1945 | 70.2% | 29.8% |

| 1949 | 72.9% | 27.1% |

| 1953 | 68.8% | 31.2% |

| 1962 | 68.2% | 31.8% |

| 1965 | 65.6% | 34.4% |

| 1969 | 68.9% | 31.1% |

| 1972 | 70.9% | 29.1% |

| 1976 | 80.1% | 19.9% |

| 1979 | 79.5% | 20.5% |

| 1981 | 75.2% | 24.8% |

| 1983 | 69.1% | 30.9% |

| 1986 | 68.1% | 31.9% |

| 1989 | 64.3% | 35.7% |

| 1992 | 62.8% | 37.2% |

| 1995 | 61.5% | 38.5% |

| 1998 | 61.9% | 38.1% |

| 2001 | 66.6% | 33.4% |

| 2004 | 65.7% | 34.3% |

| 2007 | 65.4% | 34.6% |

| 2010 | 64.6% | 35.4% |

Wealth concentration

[edit]Wealth concentration is a process by which created wealth, under some conditions, can become concentrated by individuals or entities. Those who hold wealth have the means to invest in newly created sources and structures of wealth, or to otherwise leverage the accumulation of wealth, and are thus the beneficiaries of even greater wealth.

Economic conditions

[edit]

The first necessary condition for the phenomenon of wealth concentration to occur is an unequal initial distribution of wealth. The distribution of wealth throughout the population is often closely approximated by a Pareto distribution, with tails which decay as a power-law in wealth. (See also: Distribution of wealth and Economic inequality). According to PolitiFact and others, the 400 wealthiest Americans had "more wealth than half of all Americans combined."[33][34][35][36] Inherited wealth may help explain why many Americans who have become rich may have had a "substantial head start".[37][38] In September 2012, according to the Institute for Policy Studies, "over 60 percent" of the Forbes 400 Richest Americans "grew up in substantial privilege".[39]

The second condition is that a small initial inequality must, over time, widen into a larger inequality. This is an example of positive feedback in an economic system. A team from Jagiellonian University produced statistical model economies showing that wealth condensation can occur whether or not total wealth is growing (if it is not, this implies that the poor could become poorer).[45]

Joseph E. Fargione, Clarence Lehman and Stephen Polasky demonstrated in 2011 that chance alone, combined with the deterministic effects of compounding returns, can lead to unlimited concentration of wealth, such that the percentage of all wealth owned by a few entrepreneurs eventually approaches 100%.[46][47]

Correlation between being rich and earning more

[edit]Given an initial condition in which wealth is unevenly distributed (i.e., a "wealth gap"[48]), several non-exclusive economic mechanisms for wealth condensation have been proposed:

- A correlation between being rich and being given high-paid employment (oligarchy).

- A marginal propensity to consume low enough that high incomes are correlated with people who have already made themselves rich (meritocracy).

- The ability of the rich to influence government disproportionately to their favor thereby increasing their wealth (plutocracy).[49]

In the first case, being wealthy gives one the opportunity to earn more through high paid employment (e.g., by going to elite schools). In the second case, having high paid employment gives one the opportunity to become rich (by saving your money). In the case of plutocracy, the wealthy exert power over the legislative process, which enables them to increase the wealth disparity.[50] An example of this is the high cost of political campaigning in some countries, in particular in the US (more generally, see also plutocratic finance).

Because these mechanisms are non-exclusive, it is possible for all three explanations to work together for a compounding effect, increasing wealth concentration even further. Obstacles to restoring wage growth might have more to do with the broader dysfunction of a dollar dominated political system particular to the US than with the role of the extremely wealthy.[51]

Counterbalances to wealth concentration include certain forms of taxation, in particular wealth tax, inheritance tax and progressive taxation of income. However, concentrated wealth does not necessarily inhibit wage growth for ordinary workers with low wages.[52]

The investor, billionaire, and philanthropist Warren Buffett, one of the wealthiest people in the world,[53] voiced in 2005 and once more in 2006 his view that his class, the "rich class", is waging class warfare on the rest of society. In 2005 Buffett said to CNN: "It's class warfare, my class is winning, but they shouldn't be."[54] In a November 2006 interview in The New York Times, Buffett stated that "[t]here’s class warfare all right, but it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning."[55]

Redistribution of wealth and public policy

[edit]In many societies, attempts have been made, through property redistribution, taxation, or regulation, to redistribute wealth, sometimes in support of the upper class, and sometimes to diminish economic inequality.

Examples of this practice go back at least to the Roman Republic in the third century B.C.,[56] when laws were passed limiting the amount of wealth or land that could be owned by any one family. Motivations for such limitations on wealth include the desire for equality of opportunity, a fear that great wealth leads to political corruption, to the belief that limiting wealth will gain the political favor of a voting bloc, or fear that extreme concentration of wealth results in rebellion.[57] Various forms of socialism attempt to diminish the unequal distribution of wealth and thus the conflicts and social problems arising from it.[58]

During the Age of Reason, Francis Bacon wrote "Above all things good policy is to be used so that the treasures and monies in a state be not gathered into a few hands… Money is like fertilizer, not good except it be spread."[59]

The rise of Communism as a political movement has partially been attributed to the distribution of wealth under capitalism in which a few lived in luxury while the masses lived in extreme poverty or deprivation. However, in the Critique of the Gotha Programme, Marx and Engels criticized German Social Democrats for placing emphasis on issues of distribution instead of on production and ownership of productive property.[60] While the ideas of Marx have nominally influenced various states in the 20th century, the Marxist notions of socialism and communism remains elusive.[61][vague]

On the other hand, the combination of Labour movement, technology, and social liberalism has diminished extreme poverty in the developed world today, though extremes of wealth and poverty continue in the Third World.[62]

In the Outlook on the Global Agenda 2014 from the World Economic Forum the widening income disparities come second as a worldwide risk.[63][64] According to a 2009 meta-analysis by Paul and Moser, countries with high income inequality and poor unemployment protections experience worse mental health outcomes among the unemployed.[65]

See also

[edit]- Wealth inequality in the United States

- Wealth distribution in Europe

- Distributive justice

- Desert (philosophy)

- Generational accounting

- Cycle of poverty

- Gini coefficient

- Social mobility

- Social inequality

- Economic mobility

- Economic inequality

- Kinetic exchange models of markets

- List of countries by financial assets

- List of countries by total private wealth

- List of countries by wealth per adult

- List of sovereign states by wealth inequality

References

[edit]- ^ Davies, James B.; Sandström, Susanna; Shorrocks, Anthony F.; Wolff, Edward N. "Estimating the World Distribution of Household Wealth" (PDF). Institution/Country: University of Western Ontario, Canada; WIDER-UNU. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 2, 2020. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ "Free exchange: The real wealth of nations". The Economist. June 30, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ^ "Inclusive Wealth Report – IHDP". Ihdp.unu.edu. July 9, 2012. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ^ "Why it is hard to share the wealth". New Scientist. March 12, 2005. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c Davies, J.B.; Shorrocks, A.F. (2000). "The distribution of wealth". Handbook of Income Distribution. 1: 605–675. doi:10.1016/S1574-0056(00)80014-7.

- ^ Kappes, Sylvio; Rochon, Louis-Philippe; Vallet, Guillaume (2023-03-02). Central Banking, Monetary Policy and Income Distribution. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-80037-193-4.

- ^ Modigliani, Franco; Brumberg, Richard (1954). "Utility analysis and the consumption function: an interpretation of cross-section data". In Kurihara, Kenneth K. (ed.). Post-Keynesian Economics (1962). Rutgers University Press. pp. 388–436.

- ^ Ando, A.; Modigliani, F. (1963). "The" life cycle" hypothesis of saving: Aggregate implications and tests". The American Economic Review. 53: 55–84.

- ^ McGuire, R. H.; Netting, R. M. (1982). "Leveling Peasants? The Maintenance of Equality in a Swiss Alpine Community". American Ethnologist. 9 (2): 269–290. doi:10.1525/ae.1982.9.2.02a00040.

- ^ Smith, M. E.; Dennehy, T.; Kamp-Whittaker, A.; Colon, E.; Harkness, R. (2014). "Quantitative measures of wealth inequality in ancient central Mexican communities". Advances in Archaeological Practice. 2 (4): 311–323. doi:10.7183/2326-3768.2.4.XX.

- ^ Kohler, Timothy; Smith, Michael; Bogaard, Amy; Feinman, Gary; Peterson, Christian; Betzenhauser, Alleen (2017). "Greater post-Neolithic wealth disparities in Eurasia than in North America and Mesoamerica". Nature. 551 (7682): 619–622. Bibcode:2017Natur.551..619K. doi:10.1038/nature24646. PMC 5714260. PMID 29143817.

- ^ "62 people own same as half world – Oxfam | Press releases | Oxfam GB". Oxfam.org.uk. January 18, 2016. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ a b Davidson, Jacob (January 21, 2015). "Yes, Oxfam, the Richest 1% Have Most of the Wealth. But That Means Less Than You Think". Money. Archived from the original on April 27, 2022.

- ^ The World Distribution of Household Wealth. James B. Davies, Susanna Sandstrom, Anthony Shorrocks, and Edward N. Wolff. December 5, 2006.

- ^ The rich really do own the world December 5, 2006

- ^ "The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on July 16, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ "Inequality kills". Oxfam International. January 19, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ "World's 10 richest men see their wealth double during Covid pandemic". the Guardian. January 17, 2022. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ "Wealth of world's 10 richest men doubled in pandemic, Oxfam says". BBC News. January 17, 2022. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Global wealth report". Credit Suisse. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Global Wealth Report 2013". credit-suisse.com. Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ Kromkowski, "Who owns Baltimore", CSE/HGFA, 2007.

- ^ "United states Census Bureau".

- ^ a b Source Credit Suisse, Research Institute – Global Wealth Databook 2021

- ^ a b c d Wealth, Income, and Power Archived 2011-10-20 at the Wayback Machine by G. William Domhoff of the UC-Santa Barbara Sociology Department

- ^ Data for the following table obtained from UNU-WIDER World Distribution of Household Wealth Report Archived July 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine (The University of California also hosts a copy of the report)

- ^ Financial world dominated by a few deep pockets. By Rachel Ehrenberg. September 24, 2011; Vol.180 #7 (p. 13). Science News. Citation is in the right sidebar. Paper is here [1] with PDF here [2].

- ^ a b "Evolution of wealth indicators, USA, 1913-2019". WID.world. World Inequality Database. 2022. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b "Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2019 to 2022" (PDF). Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US). October 2023. p. 12 (Table 2). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 25, 2023.

- ^ Fig. 2 of Sullivan, Briana (July 2025). "Wealth of Households: 2023 (P70BR-211)" (PDF). US Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 26, 2025.

- ^ Sullivan, Brianna; Hays, Donald; Bennett, Neil (June 2023). "The Wealth of Households: 2021 / Current Population Reports / P70BR-183" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. p. 5 (Figure 2). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 24, 2024.

- ^ Sullivan, Briana (July 2025). "Wealth of Households: 2023 (P70BR-211)" (PDF). US Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 26, 2025.

- ^ a b Kertscher, Tom; Borowski, Greg (March 10, 2011). "The Truth-O-Meter Says: True – Michael Moore says 400 Americans have more wealth than half of all Americans combined". PolitiFact. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ a b Moore, Michael (March 6, 2011). "America Is Not Broke". Huffington Post. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ a b Moore, Michael (March 7, 2011). "The Forbes 400 vs. Everybody Else". michaelmoore.com. Archived from the original on March 9, 2011. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ a b Pepitone, Julianne (September 22, 2010). "Forbes 400: The super-rich get richer". CNN. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ a b Bruenig, Matt (March 24, 2014). "You call this a meritocracy? How rich inheritance is poisoning the American economy". Salon. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- ^ a b Staff (March 18, 2014). "Inequality – Inherited wealth". The Economist. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- ^ a b Pizzigati, Sam (September 24, 2012). "The 'Self-Made' Hallucination of America's Rich". Institute for Policy Studies. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- ^ a b Occupy Wall Street And The Rhetoric of Equality Forbes November 1, 2011, by Deborah L. Jacobs

- ^ Working Paper No. 589 Recent Trends in Household Wealth in the United States: Rising Debt and the Middle-Class Squeeze – an Update to 2007 by Edward N. Wolff, Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, March 2010

- ^ Norton, M. I., & Ariely, D., "Building a Better America – One Wealth Quintile at a Time", Perspectives on Psychological Science, January 2011 6: 9-12

- ^ 1922–1989 data from Wolff (1996), 1992–2010 data from Wolff (2012)

- ^ "Trends in the Distribution of Family Wealth, 1989 to 2022". Congressional Budget Office. 2 October 2024.

- ^ Burdaa, Z.; et al. (January 22, 2001). "Wealth Condensation in Pareto Macro-Economies" (PDF). Physical Review E. 65 (2) 026102. arXiv:cond-mat/0101068. Bibcode:2002PhRvE..65b6102B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.65.026102. PMID 11863582. S2CID 8822002. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 18, 2021. Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- ^ Joseph E. Fargione et al.: Entrepreneurs, Chance, and the Deterministic Concentration of Wealth.

- ^ Simulation of wealth concentration according to Fargione, Lehman and Polasky

- ^ Rugaber, Christopher S.; Boak, Josh (January 27, 2014). "Wealth gap: A guide to what it is, why it matters". AP News. Archived from the original on March 16, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Batra, Ravi (2007). The New Golden Age: The Coming Revolution against Political Corruption and Economic Chaos. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-7579-9. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ Channer, Harold Hudson (July 25, 2011). "TV interview with Dr. Ravi Batra". Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ Bessen, James (2015). Learning by Doing: The Real Connection between Innovation, Wages, and Wealth. Yale University Press. pp. 226–27. ISBN 978-0300195668.

The obstacles to restoring wage growth might have more to do with the broader dysfunction of our dollar- dominated political system than with the particular role of the extremely wealthy.

- ^ Bessen, James (2015). Learning by Doing: The Real Connection between Innovation, Wages, and Wealth. Yale University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0300195668.

However, concentrated wealth does not necessarily inhibit wage growth.

- ^ "The World's Billionaires". forbes.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ Buffett: 'There are lots of loose nukes around the world' Archived 30 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine CNN.com

- ^ Buffett, Warren (26 November 2006). "In Class Warfare, Guess Which Class is Winning". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017.

- ^ Livy, Rome and Italy: Books VI-X of the History of Rome from its Foundation, Penguin Classics, ISBN 0-14-044388-6

- ^ "… A perceived sense of inequity is a common ingredient of rebellion in societies …", Amartya Sen, 1973

- ^ "The Spirit Level" by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett;Bloomsbury Press 2009

- ^ Francis Bacon, Of Seditions and Troubles

- ^ Critique of the Gotha Program, Karl Marx. Part I: "Quite apart from the analysis so far given, it was in general a mistake to make a fuss about so-called distribution and put the principal stress on it."

- ^ Archie Brown, The Rise and Fall of Communism, Ecco, 2009, ISBN 978-0-06-113879-9

- ^ Jeffrey D. Sachs, The End of Poverty, Penguin, 2006, ISBN 978-0-14-303658-6

- ^ "Outlook on the Global Agenda 2014 – Reports". Reports.weforum.org. World Economic Forum. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ "178 Oxfam Briefing Paoer" (PDF). Oxfam.org. January 20, 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 8, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ "The toll of job loss". www.apa.org. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

![]() This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

External links

[edit]- U.N. statistics – Distribution of Income and Consumption; wealth and poverty

- Research on the World Distribution of Household Wealth (UNU-WIDER) Archived December 21, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- CIA World Factbook: Field Listing – Distribution of family income – Gini index

- Annual income of richest 100 people enough to end global poverty four times over. Oxfam International, January 19, 2013.

Wealth surveys

[edit]Many countries have national wealth surveys, for example:

- The British Wealth and Assets Survey

- The Italian Survey on Household Income and Wealth

- The euro area Household Finance and Consumption Survey

- The US Survey of Consumer Finances

- The Canadian Survey of Financial Security

- The German Armuts- und Reichtumsbericht der Bundesregierung

Additional data, charts, and graphs

[edit]- Wealth, Income, and Power by G. William Domhoff

- PowerPoint presentation: Inequalities of Development – Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient

- Article on The World Distribution of Household Wealth report.

- The Federal Reserve Board – Survey of Consumer Finances

- Survey of Consumer Finances 1998–2004 charts – pdf

- Survey of Consumer Finances 1998–2004 data

and resulting Gini indices for mean incomes: 1989: 51.1 Archived April 23, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, 1992: 47.8 Archived April 23, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, 1995: 49.0 Archived April 23, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, 1998: 50.4 Archived April 23, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, 2001: 52.6 Archived April 23, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, 2004: 51.4 Archived April 23, 2021, at the Wayback Machine - Changes in the Distribution of Wealth in the U.S., 1989–2001

- Report on Net Worth and Asset Ownership of Households

- Projections of the Number of Households in the U.S. 1995–2010

- The System of National Accounts (SNA): comparison of U.S. national accounts statistics with those of other countries

- World Trade Organization: Resources

- Champagne Glass infographic of global wealth distribution from Dalton Conley's You May Ask Yourself: An Introduction to Thinking Like a Sociologist textbook which was adapted from the 1992 UNDP original

Distribution of wealth

View on GrokipediaDefinitions and Concepts

Definition and Components of Wealth

Wealth in economic terms refers to the net worth of an individual, household, or entity, computed as the total value of assets minus total liabilities.[7][8] This stock measure contrasts with income, which represents a flow of resources over time, and emphasizes accumulated resources that can generate future consumption or production capacity.[9] Economists typically focus on marketable assets—those convertible to cash—excluding non-marketable elements like human capital (e.g., skills or future earnings potential) due to measurement difficulties and lack of transferability.[10] Assets constituting wealth fall into two primary categories: financial and non-financial. Financial assets include liquid holdings such as bank deposits, stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and retirement accounts like pensions or 401(k)s, which represented significant portions of U.S. household wealth in recent surveys.[11] Non-financial assets encompass real estate (primary residences and investment properties), business equity, vehicles, and consumer durables (e.g., appliances), with home equity and retirement accounts comprising the majority of aggregate U.S. household wealth as of 2022.[12] These components vary by jurisdiction and methodology; for instance, international reports often aggregate them to assess global net worth.[13] Liabilities subtract from gross assets to yield net wealth and include mortgages, consumer loans, credit card debt, and other borrowings.[9] High leverage, such as mortgage debt against real estate, can amplify wealth volatility, as asset appreciation increases net worth while debt burdens constrain liquidity.[14] In distribution analyses, net wealth captures economic security, buffering against shocks like unemployment, though zero or negative net worth affects about 10% of U.S. households as of 2023.[15] Valuation relies on market prices where available (e.g., traded securities) or estimates for illiquid assets (e.g., appraised real estate), introducing challenges in comparability across contexts.[7] Public data from sources like the U.S. Federal Reserve's Survey of Consumer Finances or international bodies provide standardized breakdowns, revealing that real estate and equities dominate for wealthier households, while lower percentiles hold more in durables and fewer liabilities.[11][14]Distinction from Income and Measurement Challenges

Wealth constitutes the accumulated stock of assets—such as financial holdings, real estate, businesses, and other valuables—net of liabilities, providing a measure of an individual's or household's total economic resources at a given point.[9] Income, by contrast, is the periodic flow of resources from earnings like wages, salaries, rents, dividends, and transfers, reflecting current economic activity rather than historical accumulation.[9] [16] This distinction implies that wealth distribution captures intergenerational transfers, savings rates, and capital returns, which amplify concentration among those with initial advantages, whereas income distribution is more influenced by labor market dynamics and is generally less skewed.[17] Empirical evidence confirms greater inequality in wealth than income; for example, in OECD countries, the top 10% of households hold 50-70% of total wealth but only 30-45% of income, yielding Gini coefficients for wealth often exceeding 0.6-0.7 compared to 0.3-0.4 for income.[17] [18] Wealth's persistence across generations—via inheritance and compounding returns—further entrenches disparities, unlike income, which can fluctuate with employment or policy changes.[19] Assessing wealth distribution faces inherent methodological hurdles beyond those for income, primarily due to its static, heterogeneous nature. Household surveys, a common source, systematically undercapture the top tail through non-response, privacy concerns, and underreporting by high-wealth individuals, biasing inequality estimates downward and distorting trends.[20] [21] Tax and administrative records provide broader coverage but exclude unrealized gains, offshore assets, and non-taxable holdings like trusts, while relying on self-valuation for illiquid items such as private equity or collectibles, which introduces appraisal inconsistencies.[20] [22] Cross-national comparability exacerbates these issues, as definitions of includable assets vary (e.g., pension rights or human capital in some frameworks but not others), and informal economies in developing regions obscure unrecorded holdings.[21] [23] Specialized surveys like the U.S. Survey of Consumer Finances oversample affluent households to mitigate underrepresentation, yet even these yield divergent results from panel data when measuring net worth dynamics.[22] Overall, these challenges imply that reported wealth inequality metrics likely understate true concentrations at the apex, necessitating hybrid approaches combining surveys with big data or imputations for robust analysis.[19][21]Theoretical Frameworks for Distribution

In neoclassical economics, the marginal productivity theory of distribution asserts that under competitive conditions, each factor of production—labor, capital, land—earns a return equivalent to its marginal contribution to output, as formalized by John Bates Clark in the 1890s.[24] This framework implies that wealth disparities arise from variations in productivity, such as differences in skill, innovation, or capital deployment, with markets allocating rewards based on value added rather than arbitrary shares. Empirical models incorporating this theory, often via general equilibrium simulations, demonstrate how heterogeneous agent abilities and returns generate observed skewness in wealth holdings, particularly when combined with savings behavior and risk aversion.[25] Critiques of marginal productivity emphasize market imperfections, including monopoly power and rent-seeking, which allow factors to capture supra-marginal returns disconnected from productive contributions. For instance, Joseph Stiglitz's models highlight how incomplete information and bargaining asymmetries lead to persistent inequality beyond productivity differences, challenging the theory's reliance on perfect competition.[26] Recent quantitative frameworks extend this by integrating rent-generating mechanisms, such as intellectual property protections or financial leverage, which amplify wealth concentration through returns uncorrelated with marginal output.[27] Marxist theory, conversely, attributes wealth distribution to class dynamics and exploitation via surplus value, where workers generate value exceeding their wages, with the excess appropriated by capital owners to fuel accumulation.[28] Karl Marx argued this process inherently concentrates wealth in fewer hands, as reinvested surplus expands capital while proletarianizing labor, predicting escalating inequality absent revolutionary redistribution. However, empirical tests of Marxist predictions, such as proletarian pauperization, find limited support in long-run data from industrialized economies, where wage shares have fluctuated but not monotonically declined due to technological shifts and institutional factors.[29] Human capital theory posits that investments in education, training, and skills drive earnings differentials, translating into wealth gaps through compounded lifetime income and savings.[30] Developed by economists like Gary Becker, it explains inequality as arising from initial endowments, access to education, and returns to ability, with evidence from panel data showing that human capital adjustments reduce measured wealth dispersion by 20-30% in U.S. households.[31] Yet, this overlooks intergenerational transmission via bequests and financial capital returns, which dominate top-tail inequality; heterogeneous-agent models reveal that bequest motives and precautionary savings amplify disparities even among equal human capital cohorts.[32] Macro-level frameworks, such as those emphasizing multiplicative wealth processes, account for Pareto-distributed tails observed globally, where random returns on assets—independent of initial productivity—generate exponential divergence over time.[33] These models, calibrated to historical data, underscore causal roles for low time preference, entrepreneurial risk-taking, and institutional enforcement of property rights in sustaining unequal distributions, rather than zero-sum extraction. Institutional variations, including taxation and inheritance laws, modulate outcomes, with simulations indicating that progressive bequest taxes can flatten distributions without curtailing growth incentives.[34] Overall, no single framework fully reconciles theory with empirics, as wealth skewness persists across regimes, pointing to interplay between individual heterogeneity, stochastic dynamics, and policy structures.Historical Context

Pre-Industrial and Early Modern Periods

In pre-industrial societies, prior to the widespread adoption of mechanized production around 1800, wealth was primarily embodied in land, livestock, and rudimentary capital goods, with ownership concentrated among a narrow elite comprising nobility, clergy, and monarchs who extracted rents and tribute from the agrarian majority. The bulk of the population—peasants and serfs bound to the land—held minimal assets, often confined to personal tools, household goods, and subsistence plots, fostering structural barriers to accumulation through feudal obligations like corvée labor and manorial dues. This resulted in profound inequality, as reconstructed from probate inventories and tax assessments; for instance, in England between 1327 and 1332, the wealth Gini coefficient stood at 0.725, indicating that the top decile controlled the vast majority of resources while the bottom half possessed near-zero net worth.[35] Similar patterns prevailed across feudal Europe, where nobility constituted less than 1-2% of the population yet dominated land tenure, with church holdings further entrenching elite control—evident in 14th-century Bohemia, where wealth Gini estimates ranged from 0.739 to 0.777 based on urban records from Budweis in 1416.[36] Empirical analyses of social tables from 28 pre-industrial societies, spanning ancient Greece to 18th-century Asia and the Americas, reveal income Gini coefficients averaging 0.45 (with a range of 0.25 to 0.65), underscoring elite extraction as a common feature driven by Malthusian dynamics: population pressures eroded subsistence levels for the masses while elites captured surpluses via institutional rents.[37] Wealth disparities exceeded income inequality due to indivisible assets like estates, which compounded intergenerational transmission; in medieval Spain, labor income Gini in urban centers like Murcia circa 1600 hovered around 0.51, but total wealth metrics reflected even steeper pyramids, with the top 1% amassing shares upwards of 20-30% in reconstructed distributions.[38] These estimates, derived from archival sources such as wills and censuses, likely understate top-end concentration owing to tax evasion by elites and incomplete records of movable wealth, yet they consistently depict societies where 80-90% of aggregate wealth accrued to 10% of households.[39] The early modern period (circa 1500-1800) saw continuity in this elite dominance amid nascent commercialization, as mercantile gains and colonial ventures augmented rather than diffused wealth, with European nobility adapting enclosures and joint-stock enterprises to consolidate holdings. In England, wealth inequality intensified, with the Gini rising to 0.756 by 1524-1525, fueled by inflationary pressures from New World silver inflows that disproportionately benefited landowners while eroding peasant tenures.[35] Across 13 early modern European social tables, income Gini averaged 0.47, reflecting persistent agrarian extraction despite urban growth; associational bodies like guilds mitigated some local disparities but failed to alter macro-level pyramids, as land reforms and primogeniture preserved elite shares.[40] In non-European contexts, such as Ottoman or Mughal domains, analogous concentrations persisted through iqta land grants and zamindari systems, where rulers and warlords skimmed agricultural surpluses, yielding comparable high-inequality equilibria verifiable via fiscal ledgers. Overall, from 1300 to 1800, European wealth inequality trended upward monotonically, as capital returns outpaced demographic leveling, setting a baseline of elite capture that industrialization would later disrupt.[41]19th and 20th Century Shifts

The Industrial Revolution, beginning in Britain around 1760 and spreading to Europe and North America by the mid-19th century, marked a pivotal shift toward greater wealth concentration among industrial capitalists and landowners. As manufacturing expanded, returns on capital—through factories, machinery, and railroads—outpaced wage growth for the emerging industrial proletariat, leading to rising inequality within industrializing nations. In Britain, data from 1270 to 1940 indicate that increasing inequality drove the reallocation of resources toward manufacturing, with the Gini coefficient for income reaching approximately 0.60 by 1800, where the wealthiest 20% captured 65% of total income.[42][43] Similarly, in the United States, 19th-century industrialization elevated wealth disparities, as evidenced by estate tax records showing heightened concentration by 1870, with the top decile's share of wealth surpassing pre-industrial levels due to rapid capital accumulation in sectors like railroads and steel.[44] Globally, this era coincided with colonial expansion, where European powers extracted resources from Asia, Africa, and the Americas, exacerbating international wealth gaps; per capita incomes in the West diverged sharply from subsistence levels elsewhere, with the income ratio between the richest and poorest countries widening to around 50:1 by the late 19th century.[45][46] The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw inequality peak in many Western economies, exemplified by the U.S. Gilded Age (circa 1870–1900), where fortunes amassed by figures like John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie reflected top 1% wealth shares approaching 45% by 1916, driven by unchecked monopoly formation and minimal taxation.[47] In Europe, similar patterns emerged, with industrial elites in France and Germany holding disproportionate assets amid urbanization that left rural and urban poor with stagnant shares. However, the Great Depression (1929–1939) initiated a reversal, as asset deflation—particularly in stocks and real estate held by the wealthy—eroded top fortunes, while government interventions like the U.S. New Deal introduced progressive taxation and social programs that redistributed income.[48] World War II (1939–1945) accelerated this "Great Compression," destroying capital through bombings and seizures, mobilizing labor (boosting wages via unions and full employment), and imposing high marginal tax rates—up to 94% on top U.S. incomes by 1944—which compressed wealth shares; U.S. top 1% wealth share fell to about 22% by 1978.[49][47] In Europe, wartime dynamics yielded comparable Gini declines of 7–10 points in income distribution for countries like the UK and France.[49] Postwar policies sustained lower inequality until the 1970s, with welfare states, strong labor unions, and capital controls in Western Europe and North America fostering broader middle-class wealth accumulation through homeownership and pensions. In the U.S., union density peaked at 35% of the workforce in 1954, contributing to about 25% of the Gini decline from 1936–1968 via higher median wages. Globally, decolonization after 1945 allowed some former colonies to industrialize, narrowing inter-country gaps slightly by the 1970s, though within-nation inequality varied; communist regimes in the USSR and Eastern Europe enforced nominal equality but concentrated power-wealth among elites, with Gini rises of 10–20 points post-reforms. These shifts underscore how exogenous shocks (wars, depressions) and deliberate policies (taxation, labor rights) temporarily overrode capital's tendency to concentrate, though underlying dynamics like technological capital returns persisted.[50][51][52]Post-1980 Globalization and Technological Impacts

Since the 1980s, globalization—characterized by trade liberalization, capital mobility, and the integration of emerging markets like China and India—has exerted divergent effects on wealth distribution. Globally, it reduced between-country inequality by enabling rapid economic catch-up in developing nations; for instance, China's entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001 facilitated export-led growth, lifting over 800 million people out of extreme poverty between 1980 and 2020, which compressed the worldwide Gini coefficient for income from approximately 0.70 in 1980 to around 0.63 by 2016.[53] [54] However, within advanced economies, offshoring of manufacturing and services to low-wage countries displaced low-skilled workers, contributing to stagnant wages for non-college-educated labor and rising wealth gaps; in the United States, manufacturing employment fell from 19.5 million jobs in 1979 to 12.8 million by 2019, correlating with a widening premium for skilled labor.[55] [56] Technological advancements, particularly the information technology revolution and automation since the 1980s, have amplified wealth concentration through skill-biased technical change (SBTC), which disproportionately rewards high-skilled workers and capital owners. SBTC, driven by computerization and software innovations, increased the relative demand for cognitive skills, elevating the college wage premium in the US from 30% in 1980 to over 60% by 2000, while automating routine tasks displaced middle-skill occupations and widened the gap between high- and low-wage earners.[57] [58] Empirical analyses attribute roughly half of the US income inequality rise since 1980 to automation, with effects persisting into wealth accumulation as returns to capital in tech-intensive sectors outpaced labor income; the top 1% share of US net worth rose from about 23% in 1989 to 31.5% by 2023.[59] [60] These forces interacted synergistically: global supply chains amplified SBTC by allowing firms to offshore low-skill production while retaining high-skill R&D domestically, fostering "superstar" effects in winner-take-all markets like software and finance, where scale economies concentrate gains among top innovators and investors. Globally, the top 1% income share climbed from 16% in 1980 to 20.6% by 2020, with wealth inequality following suit as asset values in tech and trade-exposed sectors surged; IMF research indicates technology's role in inequality exceeds globalization's, underscoring causal primacy in labor market polarization.[61] [4] In developing economies, however, technology adoption via globalization often equalized wealth by enabling small-scale entrepreneurship, though elite capture of rents in resource sectors limited broad diffusion.[62] Overall, post-1980 dynamics reflect causal realism: productivity-enhancing integration and innovation boosted total wealth but skewed distribution toward those controlling complementary factors like skills and capital, with limited countervailing redistribution in most jurisdictions.[63]Measurement and Empirical Data

Key Metrics and Indices

The Gini coefficient quantifies wealth inequality by measuring the deviation of the wealth distribution from perfect equality, with values ranging from 0 (complete equality) to 1 (complete inequality). For wealth, which includes assets minus debts, the coefficient typically exceeds that for income due to concentration in illiquid and appreciating assets like property and equities. In the UBS Global Wealth Report 2025, country-level wealth Gini coefficients highlight extreme disparities, such as 0.82 in Brazil and Russia, and 0.81 in South Africa, reflecting structural factors including resource dependence and institutional weaknesses.[1] Percentile wealth shares offer a complementary metric, capturing concentration at the top by calculating the proportion of total net wealth held by common tier divisions in global wealth reports, including the top 1%, top 10%, middle 40%, and bottom 50% of the adult population. Globally, approximately 1.6% of adults control 48.1% of personal wealth, underscoring how risk-taking, innovation, and capital accumulation amplify disparities.[64] The World Inequality Database provides granular estimates, showing the top 1% wealth share varying by methodology but consistently high, often exceeding 35% in advanced economies like the United States at 40.5%.[6][4] The wealth pyramid, a distributional framework used in reports like UBS's, segments the global adult population into bands based on net worth thresholds (e.g., under $10,000, $10,000–$100,000, $100,000–$1 million, over $1 million) and reveals both population shares and their corresponding wealth holdings. In 2024, 40.7% of adults held less than $10,000, down from 75% in 2000, while the over-$1 million segment—comprising about 1% of adults—accounted for nearly half of total global wealth, driven by financial market gains and entrepreneurship.[1][65] Additional indices, such as the Palma ratio (ratio of top 10% wealth to bottom 40%), further emphasize tail disparities, though less standardized for wealth than income. These metrics collectively demonstrate persistent global wealth concentration, with mean wealth per adult far exceeding the median, as asset ownership skews toward higher percentiles. This occurs because asset concentration in the upper class pulls the average higher than the median through the influence of high-wealth outliers; in younger age groups like 30-39, high debt from initial housing purchases and polarization between high-asset owners and lower-asset individuals exacerbate the gap.[66][67]| Country | Wealth Gini Coefficient (2024) |

|---|---|

| Brazil | 0.82 |

| Russia | 0.82 |

| South Africa | 0.81 |

| United States | ~0.85 (estimated from shares) |

Global Wealth Distribution Statistics

Global personal wealth grew by 4.6% in 2024, reaching a new record level following a 4.2% increase in 2023, driven primarily by strong performance in financial markets and currency appreciation in key regions.[3] This growth continued a long-term upward trend, with compound annual growth of 3.4% since 2000.[3] The UBS Global Wealth Report estimates that adults with net worth exceeding USD 1 million—approximately 1.6% of the global adult population—held 48.1% of total personal wealth in 2024.[64] The global wealth pyramid illustrates stark concentration at the top. Nearly 60 million adults qualified as USD millionaires in 2024, owning roughly USD 226 trillion in combined assets, with the United States accounting for 40% of the global total and adding 379,000 new millionaires during the year.[68] [3] Within this group, "everyday millionaires" (USD 1–5 million) numbered 52 million and controlled USD 107 trillion.[3] At the base, the share of adults with wealth under USD 10,000 declined to 40.7%, while the USD 10,000–100,000 band became the largest, encompassing about 1.55 billion adults. Adults with net worth over USD 10,000 thus represent approximately the top 59% of the global adult population, including roughly 41.3% in the USD 10,000–100,000 band and 18% over USD 100,000.[3][65]| Wealth Range (USD) | Share of Adults (%) | Approximate Number of Adults (millions) | Share of Global Wealth (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 10,000 | 40.7 | ~1,550 | <1 |

| 10,000–100,000 | ~41 | ~1,550 | ~10 |

| 100,000–1 million | ~16 | ~600 | ~20 |

| >1 million | 1.6 | 60 | 48.1 |

Recent Trends and Projections to 2025

Global wealth experienced a sharp contraction of approximately 2.3% in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by robust recovery with annual growth rates exceeding 7% in both 2021 and 2022, driven primarily by rising equity markets and real estate values in advanced economies.[1] By 2023, growth moderated to around 4.2%, and in 2024, it accelerated to 4.6%, lifting total global household wealth to an estimated $510 trillion, with per-adult wealth reaching about $100,000 in nominal terms.[3] This upward trajectory reflects market-driven asset appreciation, particularly in stocks and property, amid low interest rates until mid-2022 and subsequent monetary tightening that disproportionately benefited asset holders.[1] Wealth concentration remained elevated throughout the period, with the top 10% of adults holding roughly 76% of global net personal wealth as of 2022, a figure stable from pre-pandemic levels and indicative of persistent structural disparities in asset ownership.[71] Millionaires—defined as individuals with net worth over $1 million—accounted for nearly half of global personal wealth in 2024, up from prior years due to stock market gains favoring high-net-worth portfolios.[5] Regionally, North America, led by the United States (holding 35% of global wealth), saw the strongest per-adult gains, while emerging markets like China contributed to narrowing inter-country gaps through rapid middle-class expansion, though intra-country inequality widened in many nations.[70][72] Projections through 2025 anticipate continued moderate global wealth expansion of 3-5% annually, supported by anticipated economic stabilization, technological productivity gains, and demographic shifts, though vulnerabilities from geopolitical tensions and inflation could temper asset returns.[1] A significant intergenerational wealth transfer, estimated at $83 trillion over the next 20-25 years, is underway, with the United States capturing about 29% of it, primarily through inheritances that reinforce existing concentrations among upper wealth brackets.[65] Data up to 2025 from extended historical series suggest that total wealth accumulation will surpass prior peaks, but the top 1% share may edge higher absent policy interventions disrupting capital returns, as historical patterns link inequality stability to underlying rates of return exceeding economic growth.[73] These forecasts underscore that while absolute wealth levels rise for most adults, distributional dynamics favor those with diversified, high-return assets, perpetuating pyramid-like structures observed since the 1980s.[1]Patterns and Variations

Global Overview and Pyramid Structures

Global wealth distribution exhibits extreme concentration, with the vast majority of assets held by a small fraction of the world's adult population. According to the UBS Global Wealth Report 2025, total global wealth grew by 4.6% in 2024, reaching levels that underscore persistent skewness in holdings.[3] The top 1% of adults, comprising approximately 60 million individuals, control nearly half of all personal wealth, estimated at 48.1% or $226 trillion.[64] This elite tier primarily includes those with net worth exceeding $1 million, reflecting accumulation through high-productivity investments, entrepreneurship, and asset appreciation in advanced economies.[70] The pyramid structure of global wealth further illustrates this disparity, typically segmented into tiers by net worth per adult: the base encompasses over 90% of adults with minimal holdings, while progressively narrower upper layers hold disproportionate shares. The top 10% of adults command about 85% of global wealth, leaving the bottom 90% with the remaining 15%.[74] Within the upper echelons, ultra-high-net-worth individuals (over $50 million) represent less than 0.1% of adults but account for a significant portion of the apex's value, often exceeding 10-15% of total wealth when disaggregated.[1] These figures derive from household balance sheets, netting financial and non-financial assets against debts, and exclude human capital or public entitlements.[70]| Wealth Tier (Net Worth per Adult) | Share of Adults (%) | Share of Global Wealth (%) |

|---|---|---|

| > $1 million | 1.6 | 48.1 |

| $100,000 - $1 million | ~8 | ~37 |

| <$100,000 | 90.4 | 14.9 |

Regional and National Disparities

Wealth distribution exhibits stark regional disparities, with the Americas holding approximately 39.3% of global wealth in 2024, followed by Asia-Pacific at 35.9% and Europe, Middle East, and Africa (EMEA) at 24.8%, despite the latter region's larger population share.[1] These imbalances stem from higher average wealth per adult in developed regions, driven by financial assets and real estate accumulation, while sub-Saharan Africa and parts of South Asia contribute minimally due to lower asset bases and economic output. For instance, North America's wealth growth outpaced other regions in 2024, fueled by U.S. stock market gains and a stable dollar, contrasting with slower advances in emerging markets outside Greater China.[70] Nationally, average wealth per adult varies dramatically, exceeding $500,000 in countries like Switzerland and Luxembourg as of 2023 data, while falling below $10,000 in nations such as India, Indonesia, and most African states.[1] This per capita gap underscores causal factors like institutional stability, capital markets depth, and historical capital accumulation, rather than mere population size; for example, small European economies like Iceland and Norway rank high due to resource wealth and savings rates, whereas resource-rich African countries like Nigeria lag owing to governance inefficiencies and capital flight.[1] Wealth inequality within nations further amplifies disparities, with Gini coefficients for wealth (on a 0-100 scale) reaching 89 in South Africa, 86 in Brazil, and 83 in Russia in recent estimates, indicating top deciles control over 70% of national wealth in these cases.[75] In contrast, European nations like Slovakia (Gini 62) and Slovenia exhibit lower inequality, reflecting stronger social safety nets and progressive taxation, though even there, the top 10% hold 50-60% of assets.[75] Latin America and parts of Eastern Europe display persistently high wealth concentration, linked to weak property rights and elite capture, while East Asia's disparities have moderated in countries like Japan (Gini around 65) due to broad equity participation post-1990s reforms.[72]| Region | Share of Global Wealth (2024) | Avg. Wealth Growth (2008-2023) | Example National Gini (Wealth, Recent) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Americas | 39.3% | 37.3% | U.S.: 85 |

| Asia-Pacific | 35.9% | 36.9% | China: 70 |

| EMEA | 24.8% | 25.8% | South Africa: 89 |

.svg/250px-Global_Wealth_Distribution_2020_(Property).svg.png)

.svg/2000px-Global_Wealth_Distribution_2020_(Property).svg.png)