Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

American lower class

View on Wikipedia

In the United States, the lower class are those at or near the lower end of the socioeconomic hierarchy. As with all social classes in the United States, the lower class is loosely defined and its boundaries and definitions subject to debate and ambiguous popular opinions. Sociologists such as W. Lloyd Warner, Dennis Gilbert and James Henslin divide the lower classes into two. The contemporary division used by Gilbert divides the lower class into the working poor and underclass. Service and low-rung manual laborers are commonly identified as being among the working poor. Those who do not participate in the labor force and rely on public assistance as their main source of income are commonly identified as members of the underclass. Overall the term describes those in easily filled employment positions with little prestige or economic compensation who often lack a high school education and are to some extent disenfranchised from mainstream society.[1][3][4]

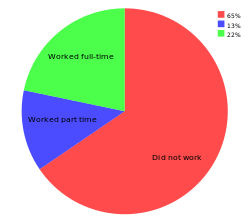

Estimates for how many households are members of this class vary with definition. According to Dennis Gilbert roughly one quarter, 25%, of US households were in the lower classes; 13% were members among the working poor while 12% were members of the underclass. While many in the lower working class are employed in service jobs, lack of participation in the labor force remains the main cause for the economic plight experienced by those in the lower classes.[1] In 2005, the majority of households (56%) in the bottom income quintile had no income earners while 65% of householders did not work. This contrasts starkly to households in the top quintile, 76% of whom had two or more income earners.[2]

Lacking educational attainment as well as disabilities are among the main causes for the infrequent employment. Many households rise above or fall below the poverty threshold, depending on the employment status of household members. While only about 12% of households fall below the poverty threshold at one point in time, the percentage of those who fall below the poverty line at any one point throughout a year is much higher. Working class as well as working poor households may fall below the poverty line if an income earner becomes unemployed.[1][4] In any given year roughly one out of every five (20%) households falls below the poverty line at some point while up to 40% may fall into poverty within the course of a decade.[3]

See also

[edit]- Affluence in the United States

- American middle class

- Household income in the United States

- Personal income in the United States

- Poorest places in the United States

- Poverty and health in the United States

- Poverty in the United States

- Social class in American history

- Social class in the United States

- Wealth inequality in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Gilbert, Dennis (1998). The American Class Structure. New York: Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 9780534505202. 0-534-50520-1.

- ^ a b "US Census Bureau, income quintilea and Top 5 Percent, 2004". Archived from the original on July 7, 2006. Retrieved July 8, 2006.

- ^ a b Thompson, William; Joseph Hickey (2005). Society in Focus. Boston, MA: Pearson. 0-205-41365-X.

- ^ a b Williams, Brian; Stacey C. Sawyer; Carl M. Wahlstrom (2005). Marriages, Families & Intimate Relationships. Boston, MA: Pearson. 0-205-36674-0.

External links

[edit]- US Census Bureau's official online income statistics forum

- Income distribution and income by race, US Census Bureau 2005

- Household income by educational attainment, US Census Bureau

- Personal income in 2004, US Census Bureau

- Median Family Income by Family Size (in 2004 inflation-adjusted dollars) from Census.gov

- Median Family Income by Number of Earners in Family (in 2004 inflation-adjusted dollars) from Census.gov

- Working Definitions ClassMatters.com

- How Class Works, The New York Times

American lower class

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Defining the Lower Class

The lower class in the United States encompasses individuals and households at the base of the socioeconomic hierarchy, defined primarily by sub-median incomes, restricted educational credentials, and engagement in low-skill, low-wage labor. This stratum includes the working poor, who maintain employment yet face chronic financial insecurity, and the underclass, characterized by entrenched poverty and limited workforce participation. According to Pew Research Center analysis of 2022 data adjusted for household size, lower-income households—constituting the lower class—had pretax incomes below two-thirds of the national median, approximately $56,600 for a three-person household.[9] Sociological frameworks, such as Dennis Gilbert's six-tier model of U.S. class structure, further delineate the lower class into the working-poor class and underclass. The working-poor class comprises semi-skilled workers in precarious roles like retail sales, food service, and manual labor, often earning under $30,000 annually with high school education or less and facing intermittent unemployment. The underclass, by contrast, involves persistent joblessness, welfare dependence, and generational poverty, with members typically possessing incomplete secondary education and residing in areas of concentrated disadvantage. Gilbert's model, outlined in his analysis of American stratification, estimates these groups together represent 13-20% of the population, emphasizing structural barriers over individual failings.[10][11] Empirical markers reinforce this definition: federal poverty thresholds for 2023 placed a family of four below $30,000 in income, aligning with lower-class status for over 11% of Americans per Census Bureau reports, many in service-sector jobs requiring minimal training. Educational attainment remains a hallmark, with lower-class adults disproportionately holding high school diplomas or GEDs at rates exceeding 40% without postsecondary credentials, correlating with occupational confinement to roles like custodians, farmworkers, and cashiers. These traits distinguish the lower class from the working class above, which enjoys greater job stability and benefits despite modest wages.[12][13][2]Key Socioeconomic Indicators

Households in the lowest income quintile, comprising the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution, received 3.1 percent of aggregate U.S. household income in 2023.[14] This quintile's upper income threshold was approximately $30,961 annually, reflecting limited earning capacity often tied to low-wage occupations or part-time work.[15] The official poverty rate in 2023 was 11.1 percent, encompassing 36.8 million people, primarily those with incomes below thresholds like $30,000 for a family of four.[12] The Supplemental Poverty Measure, which accounts for government benefits, taxes, and regional cost variations, reported a rate of 12.9 percent for the same year.[16] Homeownership rates among bottom-quintile households stood at 47 percent in 2023, an increase from prior decades but far below the 81 percent rate for the highest quintile, underscoring barriers to wealth accumulation through property.[17] Labor market engagement for this group features higher vulnerability to underemployment and economic downturns, with lower-income households experiencing disproportionate declines in wages and hours during slowdowns.[18] Overall unemployment remains low at around 4.3 percent, but structural factors like skill mismatches elevate effective joblessness risks for low-income workers.[19] Educational attainment serves as a critical indicator, with lower socioeconomic status associated with reduced academic progress and lower completion rates of higher education; for instance, adults in low-SES communities exhibit slower advancement compared to higher-SES peers.[20] In 2023, national high school graduation rates hovered near 91 percent, but disparities persist, with lower-class individuals overrepresented among those without postsecondary credentials, limiting mobility.[21] These metrics highlight persistent challenges in income stability, asset building, and human capital development for the American lower class.Historical Context

Origins in Colonial and Antebellum America

In the early colonial period, particularly in the Chesapeake colonies of Virginia and Maryland from the 1600s onward, the foundation of the American lower class emerged through the widespread use of indentured servitude to supply labor for tobacco plantations and settlements. Between half and three-quarters of European immigrants to these regions arrived as indentured servants, who contracted to work for four to seven years in exchange for passage, food, and shelter, often under harsh conditions including high mortality rates from disease and overwork.[22][23][24] Upon completing their terms, many former servants acquired small landholdings, contributing to relatively high rates of free white land ownership—estimated at 60-80% in some mid-Atlantic and New England areas by the mid-1700s—but a significant portion remained landless laborers or subsistence farmers due to soil exhaustion, limited capital, and competition for arable land.[25] Economic inequality among free whites was lower than in Britain, with average per capita incomes for free whites around £16 annually in the 1770s, yet poverty persisted among urban day laborers, vagrants, and rural squatters, prompting colonial poor laws that distinguished between "worthy" (e.g., widows, orphans) and "unworthy" poor, often binding the latter into service or auctioning their labor to minimize public costs.[26][25][27] These mechanisms reflected a causal link between immigration-driven labor surpluses and structural poverty, as rapid population growth outpaced land availability in frontier regions, forcing many into wage dependency or itinerant work without the upward mobility promised by colonial charters. By the antebellum era (roughly 1815-1861), the lower class among free whites solidified in the South as a distinct group of non-slaveholding yeomen, tenants, and laborers—comprising up to 50% of the white population in states like South Carolina and Georgia—who subsisted on marginal soils, hunted, or hired out for seasonal plantation tasks, often stigmatized by elites for idleness and moral degradation amid economic stagnation from soil depletion and reliance on slave-based agriculture.[28][29] In the North, proto-industrial wage earners in emerging textile mills and ports faced similar precarity, with low wages (e.g., 1 daily for unskilled labor in 1840s New England) and vulnerability to economic cycles, though opportunities for small proprietorship remained higher than in the plantation South.[30] This bifurcation highlighted causal factors like regional agricultural specialization and slavery's suppression of free labor markets, perpetuating a lower class defined by landlessness and chronic insecurity rather than mere transience.[31]Industrialization and the Rise of the Working Poor

The industrialization of the United States, accelerating from the 1790s with Samuel Slater's establishment of the first cotton-spinning mill in Rhode Island and gaining momentum after the War of 1812 through water-powered textile factories in New England, fundamentally altered the economic structure by shifting labor from agrarian self-sufficiency to wage-based manufacturing.[32] By the 1870s, the Second Industrial Revolution propelled expansion in steel production, railroads, and petroleum refining, transforming the nation into an industrial powerhouse where manufacturing output surged, with iron and steel production alone rising from 1.25 million tons in 1880 to over 10 million tons by 1900.[33] This era created a vast proletarian class of factory operatives, miners, and laborers, many previously farmers or artisans, who faced dependency on employers for survival amid volatile markets and mechanization that deskilled trades.[34] Mass immigration, peaking between 1880 and 1920 with over 20 million arrivals primarily from Southern and Eastern Europe, supplied cheap labor essential to industrial growth, as newcomers accepted wages and conditions often rejected by native-born workers, comprising up to 60% of large northern cities' populations by 1890 alongside their children.[35] [36] Rural-to-urban migration compounded this, reversing demographics so that by the early 1900s, only 40% of Americans lived rurally compared to nearly 60% in 1865, concentrating workers in overcrowded cities like New York and Chicago where factories demanded relentless output.[37] Urbanization exacerbated living standards, with tenements plagued by poor sanitation, disease, and inadequate infrastructure, as industrial expansion outpaced municipal services, leading to slums where families shared single rooms amid pollution and traffic.[38] [39] Factory wages remained stagnant relative to rising urban costs, with male manufacturing workers earning an average of about $11.16 per week in 1905—equivalent to roughly $2 daily after deductions—while women averaged $6.17, often insufficient to cover food, rent, and necessities for families reliant on child labor.[40] [41] Nominal wage increases, such as a nearly 20% rise in farm-related pay from 1830 to 1840, masked real declines when adjusted for inflation and the premium on city living, where a basic family budget required at least $500-600 annually by the 1890s but many households fell short.[41] Working conditions compounded penury: 12- to 16-hour shifts in hazardous environments without safety regulations, as evidenced by frequent accidents and the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist fire killing 146 garment workers, underscored a systemic exploitation where productivity gains accrued to owners rather than laborers.[42] Poverty persisted at around one-third of the population from 1900 onward, defining the working poor as those employed yet unable to escape destitution due to low bargaining power, seasonal unemployment, and lack of social supports.[43] [44] This coalescence of employed indigence birthed the modern American working poor, distinct from pre-industrial paupers by their integration into capitalist production yet marginalization from its fruits, fueling early labor unrest like the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 involving 100,000 workers protesting wage cuts.[34] Causal drivers included technological displacement reducing artisan independence and immigration suppressing wage floors, as empirical records show native workers' reluctance for factory drudgery shifted burdens to newcomers, entrenching class divides without proportional prosperity diffusion.[35] By 1900, this stratum embodied industrial capitalism's paradox: aggregate wealth creation alongside persistent individual hardship, setting precedents for 20th-century reforms.[45]20th Century Transformations

At the turn of the 20th century, rapid industrialization expanded the American lower class into a burgeoning urban proletariat, as rural migrants and over 14 million immigrants between 1900 and 1914 filled factories with low-skilled labor, enduring 12- to 16-hour shifts in hazardous conditions for wages averaging under $500 annually.[33] [35] This era's productivity gains from assembly lines and mechanization gradually elevated real wages for unskilled workers by about 50% from 1900 to 1929, though persistent poverty affected roughly one-third of the population, concentrated among Southern sharecroppers and urban tenement dwellers.[43] Labor unions, such as the American Federation of Labor founded in 1886, secured incremental reforms like the eight-hour day in some sectors by the 1910s, but strikes like the 1919 steel walkout highlighted violent employer resistance and limited bargaining power for the most marginalized.[46] The Great Depression from 1929 to 1939 devastated the lower class, driving unemployment to 25% by 1933 and slashing nominal wages by up to 50%, which pushed poverty rates back toward 45% amid farm foreclosures and urban evictions affecting over 2 million families.[47] [48] Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, enacted from 1933, introduced relief programs like the Works Progress Administration that employed 8.5 million workers by 1943 and established Social Security in 1935, providing direct aid to millions of the destitute and laying foundations for a federal safety net.[49] However, critics contend that New Deal policies, including payroll taxes and agricultural restrictions, reduced private employment by distorting markets and prolonged recovery, with unemployment lingering above 14% until wartime mobilization.[50] These interventions shifted the lower class's reliance from local charity to government dependency for some, while empirical data indicate poverty began declining post-1935 due to partial economic rebound rather than transfers alone.[51] World War II catalyzed a profound uplift, achieving virtual full employment with unemployment falling below 2% by 1943 as defense production absorbed 16 million workers, including women and minorities previously excluded, which halved poverty estimates from mid-Depression peaks through wage hikes averaging 60% in real terms for manufacturing laborers.[52] Postwar expansion from 1945 to 1973 sustained this trajectory, with GDP growth averaging 3.8% annually and rural-to-urban migration lifting farm poverty from over 40% in 1940 to under 20% by 1960, as low-skilled jobs in autos and steel offered family-sustaining incomes exceeding $5,000 yearly adjusted for inflation. Official poverty metrics, initiated in 1959 at 22.4%, reflected this momentum, dropping to 17.3% by 1965 amid broad-based prosperity that integrated much of the white working poor into middle-class stability via union contracts covering 35% of the workforce by 1954.[53] Yet, a residual underclass persisted among urban Blacks and Appalachians, with rates twice the national average, underscoring geographic and racial fractures unaddressed by growth alone.[51] Lyndon Johnson's 1964 War on Poverty, via the Office of Economic Opportunity, expanded transfers like food stamps and Medicaid, correlating with poverty falling from 19% in 1964 to 12.4% by 1969 and further to under 10% by the mid-1970s under supplemental measures accounting for in-kind benefits.[54] [53] These programs reached 30 million poor by 1966, reducing child poverty from 29% to lower levels through targeted aid, though long-term analyses reveal stagnation after initial gains, with critics attributing this to welfare disincentives for work and family stability rather than insufficient funding, as out-of-wedlock births rose amid caseloads exceeding 10 million by 1970.[55] [56] Overall, 20th-century shifts reduced absolute lower-class deprivation from 60-70% of the population circa 1900 to 12-14% by century's end, driven primarily by industrial and wartime productivity surges rather than policy alone, though the latter fostered a growing segment dependent on state support.[51]Post-1970s Shifts and Deindustrialization

![Employment trends for bottom 20%][float-right]The United States economy underwent profound structural transformations after the 1970s, transitioning from manufacturing dominance to a service-oriented model, a process accelerated by deindustrialization. Manufacturing employment peaked at 19.5 million jobs in June 1979 before embarking on a secular decline, with losses totaling 2 million jobs between 1980 and 2000 and an additional 5.5 million from 2000 to 2017, driven by automation, productivity gains, and import competition from low-wage countries.[57] [58] By 2023, manufacturing's share of total nonfarm employment had fallen to 9.7%, reflecting a broader shift where services accounted for over 80% of jobs.[59] This reconfiguration eroded the traditional pathway to economic stability for lower-class workers reliant on blue-collar industrial roles. Deindustrialization inflicted acute hardships on the American lower class, particularly in the Rust Belt states of Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Indiana, where factory closures displaced millions of non-college-educated laborers. Unionized manufacturing jobs, which offered family-sustaining wages averaging $25–$30 per hour (in 2023 dollars) with benefits, were supplanted by low-wage service-sector positions in retail, hospitality, and fast food, often paying under $15 per hour without comparable security or advancement.[60] [61] Between 1979 and 2019, real median wages for the bottom quintile stagnated or declined relative to productivity growth, contributing to a Gini coefficient rise from 0.40 in 1980 to 0.41 in 2022, as high-skill sectors captured gains while low-skill manufacturing workers faced persistent underemployment.[62] [63] Trade policies, including NAFTA in 1994 and China's WTO accession in 2001, amplified job offshoring, with estimates attributing 2–2.4 million losses to the "China shock" alone between 1999 and 2011.[58] The socioeconomic fallout manifested in elevated poverty rates and community decay in deindustrialized locales, where male labor force participation for those without college degrees dropped from 97% in 1970 to 88% by 2020, fostering reliance on government transfers and informal economies.[64] Cities like Youngstown, Ohio, and Detroit, Michigan, epitomized this erosion, with poverty rates exceeding 30% in affected neighborhoods by the 1980s and persistent vacancy undermining tax bases.[60] [65] While overall U.S. manufacturing output doubled from 1987 to 2022 due to technological efficiencies, the distributional effects widened the chasm for the lower class, as displaced workers struggled with skill mismatches and geographic immobility, hindering reabsorption into growth sectors.[66] This shift underscored causal links between industrial job scarcity and entrenched lower-class precarity, independent of aggregate economic expansion.

Demographics and Composition

Income and Poverty Metrics

The official poverty measure (OPM), calculated by the U.S. Census Bureau, sets thresholds based on pretax money income compared to family size-adjusted minimums derived from 1960s consumption data, updated for inflation but excluding noncash benefits and taxes. In 2023, the OPM rate declined to 11.1 percent from 11.5 percent in 2022, encompassing 36.8 million people, with higher rates among children at 13.7 percent and Black individuals at 17.1 percent.[12][12] The poverty threshold for a four-person family was $30,120 in the contiguous states.[67] The Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), a more comprehensive metric incorporating in-kind transfers like SNAP and housing subsidies, tax credits, and regional housing costs, rose to 12.9 percent in 2023 from 12.4 percent the prior year, affecting about 42.6 million people.[68][12] This increase reflects the expiration of pandemic-era expansions in benefits, highlighting how OPM understates effective poverty by ignoring these factors while SPM reveals greater vulnerability among working-age adults and those in high-cost areas. Child SPM poverty stood at 13.8 percent.[12] Household income distribution metrics delineate the lower class beyond strict poverty lines, often encompassing the bottom quintile or households below two-thirds of the national median. Real median household income reached $80,610 in 2023, up 4.0 percent from $77,540 in 2022.[69] The lowest quintile—bottom 20 percent—faced an upper income limit of $32,232 per the 2023 American Community Survey, with mean incomes historically around $16,000-$17,000, derived largely from low-wage service jobs, part-time work, or public assistance.[70][71] Alternative definitions, such as Pew Research's lower-income tier (below $53,740 or two-thirds of median for a three-person household, adjusted for size), captured roughly 19 percent of households, emphasizing the working poor above poverty thresholds but strained by stagnant real wages relative to costs.[9]| Income Quintile | Upper Limit (2023, ACS) | Approximate Share of Total Income |

|---|---|---|

| Lowest (Bottom 20%) | $32,232 | ~3% |

| Second | $61,657 | ~8-9% |

Educational Attainment and Employment Patterns

Educational attainment among Americans in the lower class, defined here as those in the bottom income quintile or below the poverty threshold, lags substantially behind national averages and higher socioeconomic groups. U.S. Census Bureau data indicate that lower-income households are disproportionately headed by individuals with no more than a high school diploma or equivalent, with bachelor's degree attainment rates below 15% in this group as of 2024, compared to over 40% nationally for adults aged 25 and older. High school completion rates also suffer, with dropout risks elevated among low-income youth; for instance, in earlier assessments tied to socioeconomic status, low-income families showed dropout rates exceeding 10% for ages 16-24. This pattern persists due to barriers like family instability and limited access to quality schooling, resulting in fewer advancing to postsecondary education—less than 30% of students from the bottom income quartile enroll in four-year colleges.[72][20][73] Employment patterns reflect this educational profile, with lower-class workers concentrated in low-skill, low-wage sectors prone to instability and underemployment. In 2024, nearly three-quarters of workers earning at or below the federal minimum wage were in service occupations, primarily food preparation and serving roles, alongside significant shares in retail sales, cleaning, and manual labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics data show that over 39 million workers—23% of the total workforce—earned less than $17 per hour, many in part-time or contingent positions without benefits. Unemployment rates compound these challenges: individuals with less than a high school diploma faced a 6.2% rate in 2024, versus 3.6% for high school graduates and 2.1% for those with a bachelor's degree or higher, among workers aged 25 and over.[74][75][76]| Educational Attainment (Ages 25+) | Unemployment Rate (2024) | Median Weekly Earnings (2024) |

|---|---|---|

| Less than high school | 6.2% | $682 |

| High school diploma | 3.6% | $899 |

| Some college or associate's | 3.0% | $1,050 |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 2.1% | $1,493 |