Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pink-collar worker

View on WikipediaThe examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and the United Kingdom and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (August 2022) |

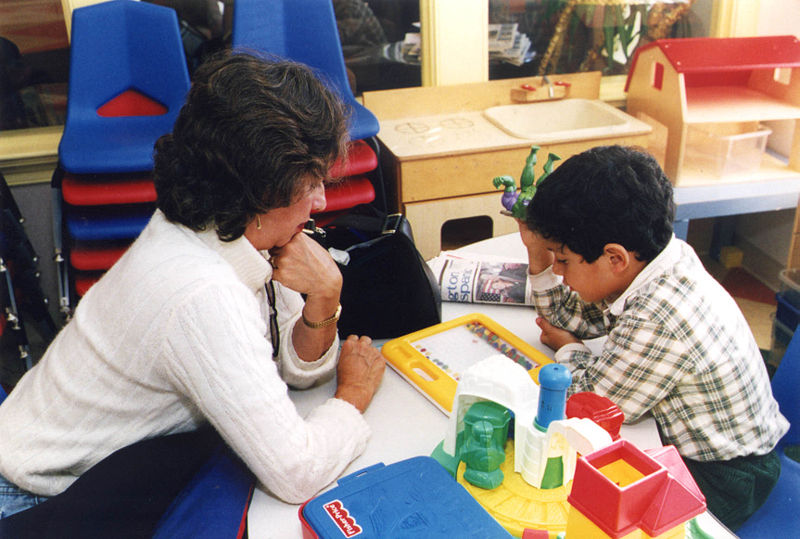

A pink-collar worker is someone working in career fields historically considered to be women's work. This includes many clerical, administrative, and service jobs as well as care-oriented jobs in therapy, nursing, social work, teaching or child care.[1] While these jobs may also be filled by men, they have historically been female-dominated (a tendency that continues today, though to a somewhat lesser extent) and may pay significantly less than white-collar or blue-collar jobs.[2]

Women's work – notably with the delegation of women to particular fields within the workplace – began to rise in the 1940s, in concurrence with World War II.[3]

History

[edit]William Jack Baumol first used the term pink collar in his 1967 article, "Macroeconomics of Unbalanced Growth: The Anatomy of Urban Crisis."[4] He introduced the term to describe a category of jobs predominantly held by women, often in clerical, administrative, or service-oriented roles. Baumol's focus was not only on the gendered nature of these jobs but also on their economic characteristics, particularly their relatively lower wages and limited opportunities for advancement compared to male-dominated professions. His analysis tied these roles to broader economic discussions about productivity and wage stagnation in labour markets. Baumol's use of the term provided an early economic framing of gendered divisions in the workforce, highlighting structural inequalities that persist in discussions of labour economics.

Louise Kapp Howe popularized the term pink collar in her 1977 book Pink Collar Workers: Inside the World of Women’s Work.[5] She used the term to describe jobs predominantly occupied by women, such as secretarial, clerical, teaching, nursing, and other caregiving or service roles. These positions were seen as extensions of traditional domestic responsibilities and were characterized by lower pay, limited career advancement opportunities, and a lack of prestige compared to "blue-collar" or "white-collar" jobs. Howe’s analysis went beyond simply identifying these roles; she explored how social expectations, gender norms, and structural inequalities confined women to these positions. She critiqued how these jobs were undervalued despite their essential contributions to the economy and society. Her work aimed to raise awareness about the economic and social disparities faced by women in the workforce and to advocate for the recognition and improvement of conditions in these roles. While Baumol's earlier usage of pink collar focused on economic categorizations, Howe expanded the term into a cultural and feminist critique, framing it as part of the broader struggle for gender equality in labour.

Occupations

[edit]Pink-collar occupations tend to be personal-service-oriented workers working in retail, nursing, and teaching (depending on the level), are part of the service sector, and are among the most common occupations in the United States. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that, as of May 2008, there were over 2.2 million persons employed as servers in the United States.[1] Furthermore, the World Health Organization's 2011 World Health Statistics Report states that there are 19.3 million nurses in the world today.[2] In the United States, women constitute 92.1% of the registered nurses that are currently employed.[6]

According to the 2016 United States Census analyzed in Barnes, et al.'s research paper, more than 95% of the construction workforce is male.[7] Due to the low population of women outside of the childcare or social workforce, state governments are miscalculating economic budgets by not accounting for most female pink-collar workers.[7] Generally, less government funding is allocated to professions and work environments that traditionally employ and retain a greater percentage of women, for example, education and social work. From the research conducted by Tiffany Barnes, Victoria Beall, and Mirya Holman, discrepancies for government representation of pink-collar jobs could primarily be due to legislatures and government employees having the perspective for only white-collar jobs and most people making budgetary decisions are men.[7] A white collar-job is typically administrative.

As explained in Buzzanell et al.'s research article, maternity leave is the time off from work a mother takes after having a child, either through childbirth or adoption.[8] In 2010, the International Labour Office explained that maternity leave is usually compensated by the employer's company, but several countries do not follow that mandate, including the United States.[8] Results from "Standpoints of Maternity Leave: Discourses of Temporality and Ability" state that many new mothers employed in pink-collar work have keyed disability or sick leave instead of time off for maternity leave.[8]

Pink-collar occupations may include:[9][10][11]

Architecture

[edit]Education

[edit]- Primary teacher

- Preschool teacher / early childhood educator / kindergarten teacher / nursery nurse

- Special Education teacher

- Teaching assistant

- Librarian / teacher-librarian

- Library assistant / library technician

Healthcare

[edit]- Midwife

- Psychiatric rehabilitation specialist

- Occupational therapist

- Physical therapist

- Speech-language pathologist / speech and language therapist

- Nutritionist / dietitian

- Dental assistant

- Social worker

- Psychologist

- Medical and health service managers

- Counselor

- Pharmacy technician

- Dental hygienist

- Lactation consultant

- Wet nurse

- Medical assistant / healthcare assistant / nurse's aide

- Hospital attendant / hospital service worker / hospital orderly

Administration

[edit]

- Advertising and promotions managers

- Bank teller

- Bookkeeper

- Marketing coordinator / marketing assistant

- Human resources manager

- Legal secretary

- Paralegal

- Public relations manager

- Receptionist

- Secretary / administrative assistant / information clerk

- Data entry clerk / Shorthand

- Meeting and convention planner

- Tax examiner / revenue agent

Entertainment

[edit]Fashion

[edit]- Hairstylist / barber / hair colorist

- Dressmaker / costume designer / tailor / Sewing / image consultant

- Cosmetologist / make-up artist / nail technician / perfumer / esthetician

- Model

- Personal stylist / fashion stylist

- Henna / Mehndi artist

- Buyer

Media

[edit]Personal care and service

[edit]- Valet

- Waitress / barista / bartender / busser

- Flight attendant / stewardess

- Museum docents / tour guide

- Casino host

- Doula / caregiver

- Babysitter / day care worker / nanny / child-care provider

- Domestic worker / Maid services attendant

- Cleaner

- Massage therapist

- Florist

- Camp counselor / non-profit volunteer coordinator / recreation director

- Relationship counselor / family therapist / social worker

- Travel agent

- Wedding planner / event planner

- Hotel housekeeper / chambermaid

- Cashier / waiting staff

- Retail clerks / retail salesperson / retail manager

- Food preparation worker / counter attendant / cafeteria attendant

- Personal care attendant / personal or home care aide

- Car attendant

- Washroom attendant

- Meter maid / parking lot attendant

Sport

[edit]Background (United States)

[edit]Historically, women were responsible for the running of a household.[12] Their financial security was often dependent upon a male patriarch. Widowed or divorced women struggled to support themselves and their children.[13]

Western women began to develop more opportunities when they moved into the paid workplace, formerly of the male domain. In the mid 19th and early 20th century women aimed to be treated as equals to their male counterparts, notably in the Seneca Falls Convention. In 1920 American women legally gained the right to vote, marking a turning point for the American women's suffrage movement; yet race and class remained as impediments to voting for some women.[14]

At the turn of the 19th century into the 20th, large numbers of single women in the United States traveled to large cities such as New York where they found work in factories and sweatshops, working for low pay operating sewing machines, sorting feathers, rolling tobacco, and other similar menial tasks.[15][16]

In these factories, workers frequently breathed dangerous fumes and worked with flammable materials.[17] In order for factories to save money, women were required to clean and adjust the machines while they were running, which resulted in accidents where women lost their fingers or hands.[17] Many women who worked in the factories earned meager wages for working long hours in unsafe conditions and as a result lived in poverty.[16]

Throughout the 20th century, women such as Emily Balch, Jane Addams, and Lillian Wald were advocates for evolving the roles of women in America.[18] These women created settlement houses and launched missions in overcrowded squalid immigrant neighborhoods to offer social services to women and children.[18]

In addition, women gradually became more involved with church activities and came to take on more leadership roles in various religious societies. The women who joined these societies worked with their members, some of whom were full-time teachers, nurses, missionaries, and social workers to accomplish their leadership tasks.[19] The Association for the Sociology of Religion was the first to elect a woman president in 1938.[19]

Invention of the typewriter

[edit]Typically, clerk positions were filled by young men who used the position as an apprenticeship and opportunity to learn basic office functions before moving on to management positions. In the 1860s and 1870s, widespread use of the typewriter made women appear better suited for clerk positions.[20] With their smaller fingers, women were perceived to be better able to operate the new machines. By 1885, new methods of note-taking and the expanding scope of businesses led office-clerk positions to be in high demand.[21] Having a secretary became a status symbol, and these new types of positions were relatively well paid.

World War I and II

[edit]

World War I sparked a demand for "pink-collar jobs" as the military needed personnel to type letters, answer phones, and perform other secretarial tasks. One thousand women worked for the U.S. Navy as stenographers, clerks, and telephone operators.[22]

In addition, Military nurses, an already "feminized" and accepted profession for women, expanded during wartime. In 1917, Louisa Lee Schuyler opened the Bellevue Hospital School of Nursing, which was the first to train women as professional nurses.[23] After completing training, female nurses worked in hospitals or more predominantly in field tents.

World War II marked the emergence of large numbers of women working domestically in industrial jobs to assist in the war effort as directed under the War Manpower Commission which recruited women to fill war manufacturing jobs.[24]

Notably, American women in World War II joined the armed services and were stationed domestically and abroad through participation in non-combat military roles and as medical personnel. One thousand female pilots joined the Women Airforce Service Pilots, one hundred and forty thousand women joined the Women's Army Corps and one hundred thousand women joined the United States Navy as nurses through WAVES in addition to administrative staff.[25]

20th-century female working world (United States)

[edit]

A typical job sought by working women in the early 20th century was a telephone operator or Hello Girl. The Hello Girls began as women who operated on telephone switchboards during WWI by answering telephones and talking to impatient callers in a calming tone.[26] The workers would sit on stools facing a wall with hundreds of outlets and tiny blinking lights. They had to work quickly when a light flashed by plugging the cord into the proper outlet. Despite the difficult work, many women wanted this job because it paid five dollars a week and provided a rest lounge for the employees to take a break.[27]

Female secretaries were also popular. They were instructed to be efficient, tough, and hardworking while also appearing soft, accommodating, and subservient.[28] Women were expected to be the protector and partner to their boss behind closed doors and a helpmate in public. These women were encouraged to go to charm schools and express their personality through fashion instead of furthering their education.[28]

Social work became a female-dominated profession in the 1930s, emphasizing a group professional identity and the casework method.[29] Social workers gave crucial expertise for the expansion of federal, state and local government, as well as services to meet the needs of the Depression.[29]

Teachers in primary and secondary schools remained female, although as the war progressed, women began to move on to better employment and higher salaries.[30] In 1940, teaching positions paid less than $1,500 a year and fell to $800 in rural areas.[30]

Women scientists found it hard to gain appointments at universities. Women scientists were forced to take positions in high schools, state or women's colleges, governmental agencies and alternative institutions such as libraries or museums.[31] Women who took jobs at such places often did clerical duties and though some held professional positions, these boundaries were blurred.[31] Some found work as human computers.

Mostly women were hired as librarians, who had been professionalized and feminized from the late 19th century. In 1920, women accounted for 88% of librarians in the United States.[31]

Two-thirds of the American Geographical Society (AGS)'s employees were women, who served as librarians, editorial personnel in the publishing programs, secretaries, research editors, copy editors, proofreaders, research assistants and sales staff. These women came with credentials from well-known colleges and universities and many were overqualified for their positions, but later were promoted to more prestigious positions.

Although female employees did not receive equal pay, they did get sabbaticals to attend university and to travel for their professions at the cost of the AGS.[31] Those women working managerial and library or museums positions made an impact on women in the work force, but still encountered discrimination when they tried to advance.

In the 1940s, clerical work expanded to occupy the largest number of women employees, this field diversified as it moved into commercial service.[32] The average worker in the 1940s was over 35 years old, married, and needed to work to keep their families afloat.[33]

During the 1950s, women were taught that marriage and domesticity were more important than a career. Most women followed this path because of the uncertainty of the post-war years.[34] Suburban housewives were encouraged to have hobbies like bread making and sewing. The 1950s housewife was in conflict between being "just a housewife" because their upbringing taught them competition and achievement. Many women had furthered their education deriving a sense of self-worth.[35]

As mentioned in the research article by Patrice Buzzanell, Robyn Remke, Rebecca Meisenbach, Meina Liu, Venessa Bowers, and Cindy Conn, as of 2016, pink-collar jobs are quickly growing in demand by both men and women.[8] Professions within pink-collar jobs are more likely to be consistent with job security and the need for employment, but salary and advancements seem to be much more slow-growing factors.[8]

Pay

[edit]A single woman working in a factory in the early 20th century earned less than $8 a week, which is equivalent to roughly less than $98 a week today.[36] If the woman was absent or was late, employers penalized them by docking their pay.[27] These women would live in boarding houses costing $1.50 a week, waking at 5:30 a.m. to start their ten-hour work day. When women entered the paid workforce in the 1920s they were paid less than men because employers thought the women's jobs were temporary. Employers also paid women less than men because they believed in the "Pin Money Theory", which said that women's earnings were secondary to that of their male counterparts. Married working women experienced lopsided stress and overload because they were still responsible for the majority of the housework and taking care of the children. This left women isolated and subjected them to their husband's control.[37]

In the early 1900s women's pay was one to three dollars a week and much of that went to living expenses.[38] In the 1900s female tobacco strippers earned five dollars a week, half of what their male coworkers made and seamstresses made six to seven dollars a week compared to a cutter's salary of $16.[39] This differed from women working in factories in the 1900s as they were paid by the piece, not receiving a fixed weekly wage.[40] Those that were pinching pennies pushed themselves to produce more product so that they earned more money.[40] Women who earned enough to live on found it impossible to keep their salary rate from being reduced because bosses often made "mistakes" in computing a worker's piece rate.[41] As well as this, women who received this kind of treatment did not disagree for fear of losing their jobs. Employers would frequently deduct pay for work they deemed imperfect and for simply trying to lighten the mood by laughing or talking while they worked.[41] In the 1937 a woman's average yearly salary was $525 compared to a man's salary of $1,027.[39] In the 1940s two-thirds of the women who were in the labor force suffered a decrease in earnings; the average weekly paychecks fell from $50 to $37.[42] This gap in wage stayed consistent, as women in 1991 only earned seventy percent of what men earned regardless of their education.[42]

Later on in the 1970s and 1980s as women began to fight for equality, they fought against discrimination in jobs where women worked and the educational institutions that would lead to those jobs.[42] In 1973 the average salaries for women were 57% compared to those of men, but this gender earnings gap was especially noticeable in pink-collar jobs where the largest number of women were employed.[43] Women were given routine, less responsible jobs available and often with a lower pay than men. These jobs were monotonous and mechanical often with assembly-line procedures.[44]

Education

[edit]Women entering the workforce had difficulty finding a satisfactory job without references or an education.[45] However, opportunities for higher education expanded as women were admitted to all-male schools like the United States service academies and Ivy League strongholds.[46] Education became a way for society to shape women into its ideal housewife. In the 1950s, authorities and educators encouraged college because they found new value in vocational training for domesticity.[47] College prepared women for future roles because while men and women were taught together, they were groomed for different paths after they graduated.[48] Education started out as a way to teach women how to be a good wife, but education also allowed women to broaden their minds.

Being educated was an expectation for women entering the paying workforce, despite the fact that their male equivalents did not need a high school diploma.[49] While in college, a woman would experience extracurricular activities, such as a sorority, that offered a separate space for the woman to practice types of social service work that was expected from her.[50]

However, not all of a woman's education was done in the classroom. Women were also educated through their peers through "dating". Men and women no longer had to be supervised when alone together. Dating allowed men and women to practice the paired activities that would later become a way of life.[50]

New women's organizations sprouted up working to reform and protect women in the workplace. The largest and most prestigious of these organizations was the General Federation of Women's Clubs (GFWC), whose members were conservative middle-class housewives. The International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) was formed after women shirtwaist makers went on strike in New York City in 1909. It started as a small walkout, with a handful of members from one shop and grew to a force of ten of thousands, changing the course of the labor movement forever. In 1910 women allied themselves with the Progressive Party who sought to reform social issues.

Another organization that grew out of women in the workforce, was the Women's Bureau of the Department of Labor. The Women's Bureau regulated conditions for women employees. As female labor became a crucial part of the economy, efforts by the Women's Bureau increased. The Bureau pushed for employers to take advantage of "women-power" and persuaded women to enter the employment market.

In 1913 the ILGWU signed the well-known "protocol in the Dress and Waist Industry" which was the first contract between labor and management settled by outside negotiators. The contract formalized the trade's division of labor by gender.

Another win for women came in 1921 when Congress passed the Sheppard–Towner Act, a welfare measure intended to reduce infant and maternal mortality; it was the first federally funded healthcare act. The act provided federal funds to establish health centers for prenatal and child care. Expectant mothers and children could receive health checkups and health advice.

In 1963 the Equal Pay Act was passed making it the first federal law against sex discrimination, equal pay for equal work (at least removed explicit base pay discrepancies based on sex), and had employers allow both men and women applicants to open positions if they qualified from the start.

Unions also became a major outlet for women to fight against the unfair treatment they experienced. Women who joined these types of unions stayed before and after work to talk about the benefits of the union, collect dues, obtain charters, and form bargaining committees.

The National Recovery Administration (NRA) was approved in May 1933. The NRA negotiated codes designed to rekindle production. It raised wages, shortened workers' hours, and increased employment for the first time maximizing hour and minimizing wage provisions benefiting female workers. The NRA had its flaws however, it only covered half of the women in the workforce particularly manufacturing and trade. The NRA regulated working conditions only for women with a job and did not offer any relief for the two million unemployed women who desperately needed it.

The 1930s proved successful for women in the workplace thanks to federal relief programs and the growth of unions. For the first time women were not completely dependent on themselves, in 1933 the federal government expanded in its responsibility to female workers. In 1938 the Fair Labor Standards Act grew out of several successful strikes. Two million women joined the workforce during the Great Depression despite negative public opinion.

21st-century female working world (United Kingdom)

[edit]Today, the economy in the United Kingdom still shows a prominent divide in a workforce with many occupations still labeled as "pink-collar".[3] 28% of women worked jobs labeled under "pink-collar" in Rotherham, a town in northern England. This study was conducted in 2010.[3] In the United Kingdom, careers within nursing and teaching are not considered pink-collar jobs anymore, but instead are labeled as white-collar. This shift is also occurring in many other countries.[3] Studies show that white-collar workers are less likely to face health disparities.[3]

Pink ghetto

[edit]"Pink ghetto" and "velvet ghetto" are terms used to describe low-paying occupations in which women historically constituted a majority of the workforce. In their 1983 book, Poverty in the American Dream: Women and Children First, authors Karin Stallard, Barbara Ehrenreich, and Holly Sklar used the term "pink collar ghetto" to discuss the increasing participation of women in the paid labour force and the persistent economic disadvantages they faced in jobs that were often dead-end, stressful and underpaid.[51]

"Pink ghetto" can also describe the placement of female managers into positions that will not lead them to the board room, thus perpetuating the "glass ceiling". This includes managerial roles in human resources, customer service, and other areas that do not contribute to the corporate "bottom line". While such roles allow women to rise in rank as managers, their careers may eventually stall and they may be excluded from the upper echelons.[52][53][54]

Pink ghetto in the field of public relations

[edit]The terms "pink collar ghetto" and "velvet ghetto" can also describe a twentieth-century phenomenon wherein the status and pay grade of a profession dropped after an influx of women workers into that field. A 1986 study by the International Association of Business Communicators explored the gendered dynamics and implications of the increasing presence of women in public relations and business communication roles. The study found that the influx of women coincided with a devaluation of the professions in terms of social prestige and financial compensation.[55] Some scholars, such as Elizabeth Toth, claimed this was partially the result of women taking technician roles instead of managerial roles, being less likely to negotiate higher pay, and being assumed to be putting family life before work, even when that was not the case.[56] Other scholars, such as Kim Golombisky, cited biases against women (especially minority and working-class women) as another cause of this phenomenon.[57] As noted below in The Mythology of “Pink Collaring”, recent studies by data scientist Felix Busch and others have shown that the devaluation of occupations due to feminization has been declining since the mid-twentieth century, becoming statistically insignificant in 2015.[58][59]

Traditionally, Feminism in public relations focused on gender equality, but new scholarship makes claims that focusing on social justice would better aid feminist cause in the field. This brings the idea of intersectionalism to the pink collar ghetto. The issue is not caused by what women lack as professionals, but caused by larger societal injustices and interlocking systems of oppression that systematically burden women.[60]

The Mythology of "Pink Collaring" in Museums and the Arts

[edit]As noted above, the authors who first described "pink collar" work, including William Jack Baumol, Louise Kapp Howe, Karin Stallard, Barbara Ehrenreich, and Holly Sklar, used the term to criticize the unfair systems trapping women in low-paying jobs. They sought to end the sexist practices and assumptions causing gender inequality in the workplace. By contrast, between 2016 and 2020, influential museum leaders in the United States reinterpreted the term "pink collar" to argue that women’s growing presence in museum professions and on art faculties would inevitably drive down pay in those fields. Proponents of this notion include Joan Baldwin and Anne Ackerson, founders of the Gender Equity in Museums Movement (GEMM), and art museum director Kaywin Feldman.[61][62][63][64][65] Feldman argued in 2020 that hiring more men in these fields was necessary to preserve their status.[66]

Proponents of this "pink collaring" theory have cited a 2016 New York Times article by columnist Claire Cain Miller.[67] In "As Women Take Over a Male-Dominated Field, the Pay Drops," Miller summarized a 2009 longitudinal study by sociologists Asaf Levanon, Paula England, and Paul Allison demonstrating a consistent twentieth-century trend wherein US occupations with a higher percentage of women offered lower median hourly wages than comparable fields that retained male majorities.[68] Miller overlooked both the historical nature of Levanon, England, and Allison’s findings and a problem that the authors themselves acknowledged, namely, that they did not investigate the mechanisms driving gender-based workplace devaluation or how resistant it might be to change.[69] Examining more current census data and using different analytical tools, the data scientist Felix Busch demonstrated in 2018 that occupational devaluation due to feminization has been steadily declining since the mid-twentieth century, that it does not affect all fields equally, and that some workers experience a wage benefit from the feminization of their field. He also showed that a field’s historical gender associations have more impact on wages than the field’s current gender composition.[70] This and other research disproves the notion that an occupation’s gender composition inevitably affects compensation.[71] Favoring men in hiring decisions because of their gender is illegal in the United States under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.[72]

Male integration

[edit]Judy Wajcman argues that technology has historically been monopolized by men, serving as a significant source of their power.[73] However, the advent of new technology has disrupted traditional blue-collar work, pushing more millennial men into pink-collar roles. Machines now perform many factory tasks once associated with masculinity, displacing unskilled or semi-skilled male workers. A 1990 study by Allan H. Hunt and Timothy L. Hunt concluded that uneducated, unskilled blue-collar workers are most vulnerable to job displacement caused by robotics.[74] Robotics and automation have not only eliminated many traditionally male-dominated roles but have also forced men into pink-collar jobs, which are often perceived as less prestigious due to associations with "women's work." Wajcman further notes that skills involving machines and physical strength are culturally tied to masculinity, while pink-collar jobs, which typically require less technical skill, are associated with women.[75] Ironically, the very technologies designed and monopolized by men are now displacing them, resulting in a shift to roles like teaching, nursing, and childcare—fields that come with significant stigma for men. Men in these professions often face discrimination and negative stereotypes, as traditional views associate men with professionalism, strength, and dominance.[76]

An analysis of 2016 United States Census data shows that approximately 78% of men were employed in cleaning and maintenance, engineering and science, production and transportation, protective services, and construction, while only 25% worked in healthcare support, personal care, education, office administration support, and social services.[7]

Men in pink-collar jobs

[edit]Despite challenges, some men in pink-collar professions achieve advantages such as higher salaries, more opportunities, and faster promotions compared to their female counterparts. However, stereotyping and hostility remain barriers, often reducing workplace performance and retention rates for men in these roles. Men who remain in these professions longer tend to adapt and experience less discrimination, while newly hired men report higher turnover rates. For example, the Australian Bureau of Statistics found that less than 20% of elementary school teachers were men, highlighting the persistent gender imbalance in such fields.[76]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b U.S. Department of Labor – Bureau of Labor Statistics (24 May 2006). "Occupational Employment and Wages – Waiters and Waitresses". US Department of Labor. Retrieved 31 December 2006.

- ^ a b "World Health Statistics 2011". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Basu, S.; Ratcliffe, G.; Green, M. (1 October 2015). "Health and pink-collar work". Occupational Medicine. 65 (7): 529–534. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqv103. ISSN 0962-7480. PMID 26272379.

- ^ Baumol, William J. (June 1967). "Macroeconomics of Unbalanced Growth: the Anatomy of Urban Crisis". The American Economic Review. 57 (3): 415–26.

- ^ Howe, Louise Kapp (1977). Pink Collar Workers: Inside the World of Women's Work. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ "Quick Facts on Registered Nurses". US Department of Labor. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d Barnes, Tiffany D.; Beall, Victoria D.; Holman, Mirya R. (2021). "Pink-Collar Representation and Budgetary Outcomes in US States". Legislative Studies Quarterly. 46 (1): 119–154. doi:10.1111/lsq.12286. ISSN 1939-9162. S2CID 219502815.

- ^ a b c d e Buzzanell, Patrice M.; Remke, Robyn V.; Meisenbach, Rebecca; Liu, Meina; Bowers, Venessa; Conn, Cindy (2 January 2017). "Standpoints of Maternity Leave: Discourses of Temporality and Ability". Women's Studies in Communication. 40 (1): 67–90. doi:10.1080/07491409.2015.1113451. ISSN 0749-1409. S2CID 148124656.

- ^ Francis, David. "The Pink-Collar Job Boom". US News. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ Sardi, Katerina (27 June 2012). "Nine pink collar jobs men want most". NBC. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ Rose, Ashley (2 March 2023). ""Pink collar" jobs are disproportionately underpaid". Indiana University Sourh Bend Student Newspaper. Archived from the original on 3 March 2023. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ Ware 1982, p. 17

- ^ Humowitz Weissman 1978, p. 333

- ^ Naffziger, Claudeen Cline; Naffziger, Ken (1974). "Development of Sex Role Stereotypes". The Family Coordinator. 23 (3): 251–259. doi:10.2307/582762. JSTOR 582762.

- ^ Gourley 2008, p. 103

- ^ a b "Sweatshops 1880-1940". National Museum of American History. 21 August 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ a b Humowitz Weissman 1978, p. 239

- ^ a b Gourley 2008, p. 99.

- ^ a b Wallace, Ruth A. (2000). "Women and Religion: The Transformation of Leadership Roles". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 39 (4): 496–508. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2000.tb00011.x. JSTOR 1388082.

- ^ Mullaney, Marie Marmo; Hilbert, Rosemary C. (February 2018). "Educating Women for Self-Reliance and Economic Opportunity: The Strategic Entrepreneurialism of the Katharine Gibbs Schools, 1911–1968". History of Education Quarterly. 58 (1): 65–93. doi:10.1017/heq.2017.49. ISSN 0018-2680.

- ^ Davies, M.W. (1982). . A Woman's Place is at the Typewriter: Office Work and Office Workers, 1870-1930. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- ^ Gourley 2008, p. 119

- ^ Gourley 2008, p. 123

- ^ "Women in the Work Force during World War II". National Archives. 15 August 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ May, Elaine Tyler (1994). Pushing the Limits. New York: Oxford University. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-19-508084-1.

- ^ "Topics in Chronicling America-Hello Girls". The Library of Congress. 29 January 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ a b Gourley 2008, p. 105

- ^ a b Rung, Margaret C. (1997). "Paternalism and Pink Collars: Gender and Federal Employee Relations, 1941–50". Business History Review. 71 (3): 381–416. doi:10.2307/3116078. JSTOR 3116078.

- ^ a b Ware 1982, p. 74

- ^ a b Ware 1982, p. 102

- ^ a b c d Monk, Janice (2003). "Women's Worlds at the American Geographical Society". Geographical Review. 93 (2): 237–257. Bibcode:2003GeoRv..93..237M. doi:10.1111/j.1931-0846.2003.tb00031.x. S2CID 144133405.

- ^ Susan M. Hartmann, The Home Front and Beyond (Boston, MA: G.K. Hall &Co., 1982), p. 94.

- ^ Humowitz Weissman 1978, p. 314

- ^ Humowitz Weissman 1978, p. 326

- ^ Humowitz Weissman 1978, p. 332

- ^ "US Inflation Calculator". US Inflation Calculator. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ Silver, Hilary. "Housework and Domestic Work," Sociological Forum 182 no.2 (1993).

- ^ Archer, Jules (1991). Breaking Barriers (New York: The Penguin Group), p. 27.

- ^ a b Woloch 1984, p. 27

- ^ a b Humowitz Weissman 1978, pp. 236–237

- ^ a b Humowitz Weissman 1978, p. 240

- ^ a b c Stoper, Emily (1991). "Women's Work, Women's Movement: Taking Stock". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 515 (1): 151–162. doi:10.1177/0002716291515001013. JSTOR 1046935. S2CID 153384038.

- ^ Humowitz Weissman 1978, p. 364

- ^ Humowitz Weissman 1978, p. 304

- ^ Gourley 2008, p. 104

- ^ Woloch 1984, p. 525

- ^ Woloch 1984, p. 500

- ^ Woloch 1984, p. 405

- ^ Humowitz Weissman 1978, p. 316

- ^ a b Woloch 1984, p. 404

- ^ Stallard, Karin; Ehrenreich, Barbara; Sklar, Holly (1983). Poverty in the American Dream: Women and Children First. Boston: South End Press.

- ^ Kleiman, Carol (8 January 2006). "Pink-collar workers fight to leave "ghetto"". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- ^ Glasscock, Gretchen (10 February 2009). "Promises Unkept in the Enduring Pink Ghetto". The New Agenda. Archived from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ Murray, Sarah (8 January 2008). "Posting Up in the Pink Ghetto". Women's Sports Foundation. Archived from the original on 16 June 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ Cline, C.G.; Toth, E.L.; Turk, J.; Masel-Walters, L.; Johnson, N.; Smith, H. (1986). The velvet ghetto: The impact of the increasing percentage of women in public relations and business communication. San Francisco: IABC Research Foundation.

- ^ "Public Relations Field: 'Velvet Ghetto'". Los Angeles Times. 30 November 1986. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ^ Golombisky, Kim (Winter 2002). "Gender Equity and Mass Communication's Female Student Majority". Journalism and Mass Communication Educator. 56 (4): 53–66. doi:10.1177/107769580205600405.

- ^ Mandel, Hadas (April 2018). "A Second Look at the Process of Occupational Feminization and Pay Reduction in Occupations". Demography. 55 (2): 669–690. doi:10.1007/s13524-018-0657-8. PMID 29569029.

- ^ Busch, Felix (1 March 2018). "Occupational Devaluation Due to Feminization? Causal Mechanics, Effect Heterogeneity, and Evidence from the United States, 1960 to 2010". Social Forces. 96 (3): 1351–1376. doi:10.1093/sf/sox077.

- ^ Golombisky, Kim (2015). "Renewing the Commitments of Feminist Public Relations Theory From Velvet Ghetto to Social Justice". Journal of Public Relations Research. 27 (5): 389–415. doi:10.1080/1062726X.2015.1086653. S2CID 146755121 – via Communication Source.

- ^ Baldwin, Joan; Ackerson, Anne (2017). Women in the Museum: Lessons from the Workplace. New York: Routledge. p. 17.

- ^ Baldwin, Joan (25 March 2019). "Museums as a Pink Collar Profession". Alliance Blog. American Alliance of Museums. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ Feldman, Kaywin (17 October 2016). "Power, Influence and Responsibility, Kaywin Feldman at the 2016 AAM Meeting". Alliance Blog. American Alliance of Museums. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ Feldman, Kaywin (17 October 2016). "Women's Locker Room Talk: Gender and Leadership in Museums". Alliance Blog. American Alliance of Museums. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ Callihan, Elizabeth; Feldman, Kaywin (2018). "Presence and Power: Beyond Feminism in Museums". Journal of Museum Education. 43 (2): 181–82. doi:10.1080/10598650.2018.1486138.

- ^ Feldman, Kaywin. "Conversation: Women Leaders in the Arts". Vimeo. Brooklyn Museum of Art. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ Miller, Claire Cain (18 March 2016). "As Women Take Over a Male-Dominated Field, the Pay Drops". New York Times. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ Levanon, Asaf; England, Paula; Allison, Paul (2009). "Occupational Feminization and Pay: Assessing Causal Dynamics Using 1950-2000 U.S. Census Data". Social Forces. 88 (2): 865–892. doi:10.1353/sof.0.0264.

- ^ Lessing, Lauren (2025). "The myth of 'pink collaring': blaming women for pay inequity in art museums". Museum Management and Curatorship. 40 (4): 1-15. doi:10.1080/09647775.2024.2431898.

- ^ Busch, Felix (March 2018). "Occupational Devaluation Due to Feminization? Causal Mechanics, Effect Heterogeneity, and Evidence from the United States, 1960 to 2010". Social Forces. 96 (3): 1-15. doi:10.1093/sf/sox077.

- ^ Murphy, Emily; Oesch, Daniel (August 2015). "The Feminization of Occupations and Change in Wages: A Panel Analysis of Britain, Germany and Switzerland". Social Forces. 94 (3): 1240.

- ^ "Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964". Statutes. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ Wajcman, Judy (1991). Feminism Confronts Technology. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0271008028.

- ^ L., Hunt, H. Allan|Hunt, Timothy (1983). Human Resource Implications of Robotics. W. ISBN 9780880990080.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wascman, Judy (2004). TechnoFeminism. Cambridge, UK and Malden, MA: Polity Press. pp. 10–23.

- ^ a b Kalokerinos, Elise K.; Kjelsaas, Kathleen; Bennetts, Steven; von Hippel, Courtney (1 August 2017). "Men in pink collars: Stereotype threat and disengagement among male teachers and child protection workers". European Journal of Social Psychology. 47 (5): 553–565. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2246. hdl:11343/292953. ISSN 1099-0992.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baumol, William J. (1967). "Macroeconomics of Unbalanced Growth: The Anatomy of Urban Crisis." The American Economic Review, 57(3), 415-426.

- Howe, Louise Kapp (1977). Pink Collar Workers: Inside the World of Women's Work. New York: Putnam.

- Gourley, Catherine (2008). Gibson Girls and Suffragists: Perceptions of Women from 1900 to 1918 (Minneapolis, MN: Twenty-First Century Books) ISBN 978-0-8225-7150-6

- Humowitz, Carol; Weissman, Michelle (1978). A History of Women in America (New York: Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith) ISBN 0-553-20762-8

- Stallard, Karin; Ehrenreich, Barbara; and Sklar, Holly (1983). Poverty in the American Dream: Women and Children First. Boston: Sounth End Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ware, Susan (1982). Holding Their Own. Boston: G.K. Hall & Co. ISBN 978-0-8057-9900-2.

- Woloch, Nancy (1984). Women and the American Experience. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-53515-9.

External links

[edit]Pink-collar worker

View on GrokipediaA pink-collar worker is an individual employed in occupations traditionally dominated by women and involving service, caregiving, or administrative tasks, such as nursing, elementary school teaching, childcare provision, and secretarial duties.[1][2] The term emerged in the 1970s to describe these roles, distinguishing them from blue-collar manual labor and white-collar professional positions, and was popularized by journalist Louise Kapp Howe's 1977 book Pink Collar Workers: Inside the World of Women's Work.[3][2] Pink-collar jobs often require interpersonal skills, emotional labor, and sometimes postsecondary training, yet they typically offer lower wages than comparable male-dominated fields, contributing to observed gender pay disparities even after controlling for occupation.[4][5] Empirical studies indicate that occupational segregation persists due to worker preferences, social norms, and barriers to male entry, with women comprising over 70% of workers in sectors like education and healthcare support.[6][7] These roles expanded significantly post-World War II as women entered the workforce en masse, but face challenges including limited upward mobility and vulnerability to economic downturns.[7]

Definition and Characteristics

Core Definition

A pink-collar worker refers to an individual employed in occupations historically dominated by women, typically involving service-oriented, caregiving, or administrative roles such as nursing, teaching, secretarial work, and retail sales.[8][9] These positions emerged prominently in the 20th century as women entered the workforce in greater numbers, often filling roles that emphasize interpersonal interaction, emotional labor, and direct service to others rather than physical production or high-level executive decision-making.[10][11] The term "pink-collar" was first introduced by economist William Jack Baumol in his 1967 article "Macroeconomics of Unbalanced Growth: The Anatomy of Urban Crisis," where he used it to describe labor sectors growing faster than manufacturing due to rising demand for personal services.[12] It gained widespread usage in the late 1970s through the writings of social critic Louise Kapp Howe, who applied it to jobs like nursing and secretarial positions to highlight their feminization and associated economic dynamics.[7] This nomenclature draws from the "blue-collar" (manual labor) and "white-collar" (professional) distinctions, with "pink" evoking traditional associations of the color with femininity, though the category reflects empirical patterns of occupational segregation rather than prescriptive gender norms.[13] Key characteristics of pink-collar work include a predominance of female participation—often exceeding 70-80% in fields like childcare and elementary education—and relatively lower wages compared to male-dominated sectors, attributed in part to the subjective valuation of emotional and relational skills over measurable outputs.[14] These roles frequently demand high levels of empathy, flexibility, and client-facing interaction, contributing to workforce stability in essential services but also exposing workers to burnout and limited upward mobility due to structural barriers like part-time scheduling and credential requirements.[11][15] Despite evolving demographics, with some diversification, the category persists as a descriptor of labor markets shaped by historical gender divisions of labor.[16]Distinctions from Other Collar Types

Pink-collar jobs are distinguished from blue-collar occupations by their emphasis on service-oriented and interpersonal tasks rather than manual or physical labor. Blue-collar roles, such as those in manufacturing, construction, or skilled trades like plumbing, typically require hands-on mechanical skills, operation of machinery, and endurance of physical demands in industrial or outdoor environments, often compensated on an hourly basis with union protections in some sectors.[17] In contrast, pink-collar positions, including nursing aides, childcare providers, and retail clerks, prioritize emotional intelligence, empathy, and direct human interaction—elements collectively termed "emotional labor"—while involving minimal heavy lifting or technical craftsmanship, though they may include light administrative duties.[14] This shift from tangible production to relational support reflects broader economic transitions toward service economies, where pink-collar work sustains social infrastructure without the visible output of blue-collar trades.[8] Compared to white-collar professions, pink-collar jobs occupy a middle ground in terms of skill requirements but diverge in prestige, autonomy, and remuneration. White-collar work, exemplified by accountants, lawyers, or executives, generally demands higher education (e.g., bachelor's degrees or beyond), analytical problem-solving, and strategic oversight in office settings, leading to salaried positions with greater upward mobility and average annual earnings exceeding $70,000 in the U.S. as of 2022 data.[17] Pink-collar roles, while sometimes requiring associate degrees or certifications (e.g., for licensed practical nurses), focus on routine caregiving or clerical support with limited decision-making latitude, resulting in median wages around $35,000–$50,000 annually for many such positions, compounded by irregular shifts and higher burnout rates from relational demands.[14] Historically female-dominated—over 70% in fields like elementary teaching or secretarial work as of recent labor statistics—this segregation contributes to persistent pay gaps, as pink-collar tasks are undervalued despite their essential societal function, unlike the credentialed expertise valorized in white-collar hierarchies.[8] These distinctions extend to working conditions and societal valuation: pink-collar employment often entails flexible but precarious schedules in community-facing venues, blending elements of both collars yet lacking the job security of unionized blue-collar trades or the professional networks of white-collar careers.[17] Empirical studies, such as those analyzing U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data from 2023, highlight how pink-collar sectors exhibit higher proportions of part-time and contingent labor (up to 25% in caregiving), underscoring their role in accommodating family responsibilities but at the cost of economic stability compared to the structured paths of other collars.[14]Key Traits and Societal Role

Pink-collar workers are characterized by their concentration in female-dominated occupations, such as nursing, teaching, and clerical roles, where women comprise 90% or more of the workforce in fields like secretarial and domestic work.[18] These positions demand high levels of interpersonal skills, empathy, and emotional labor, including managing client interactions and suppressing personal emotions to provide support, which elevates risks of burnout and psychosocial strain, particularly among sales and service workers.[14] [19] Unlike blue-collar manual labor or white-collar professional roles, pink-collar jobs emphasize service provision over physical production or executive decision-making, often involving flexible but precarious schedules with limited advancement opportunities.[8] [20] In terms of compensation, these occupations typically yield lower wages than male-dominated fields, with median earnings reflecting undervaluation of care-oriented tasks; for instance, as of 2020, women in such roles faced persistent pay gaps exacerbated by occupational segregation.[21] This stems from market dynamics where supply of female labor in caregiving exceeds demand-driven premiums seen in technical sectors.[22] Societally, pink-collar workers underpin essential functions by delivering healthcare, education, and personal services that sustain family units and workforce participation, with women holding over 50% of non-farm payroll jobs by 2020 largely through these contributions.[22] Their roles facilitate causal chains of human capital development—nurturing children, aiding the elderly, and supporting administrative efficiency—yet systemic underpayment perpetuates economic inequalities, as emotional and relational demands receive minimal premium despite irreplaceability in non-automatable care economies.[23] [21] High female representation, such as 93% in secretarial positions persisting from 1940 levels, underscores entrenched gender norms channeling women into these vital but lower-status supports.[7]Historical Development

Pre-20th Century Roots

In pre-20th century Western societies, women's paid labor primarily consisted of domestic service, which encompassed tasks such as cleaning, cooking, childcare, and laundry for households outside their own, serving as a direct precursor to modern service-oriented pink-collar roles. This occupation dominated female employment, particularly among unmarried women and immigrants, due to limited alternatives shaped by social norms confining women to extensions of household duties. In the United States before the Civil War, domestic service was the most common reported occupation for women, often involving live-in arrangements that blurred lines between employment and extended family care.[24] By the mid-19th century in England, domestic service accounted for nearly 25 percent of adult women's paid work, with nearly 9 percent of adult women engaged in it by 1851.[25] These roles emphasized personal attentiveness and relational labor, mirroring the interpersonal focus of later pink-collar jobs. Caregiving professions like nursing and midwifery further exemplified early pink-collar foundations, rooted in women's traditional community and family-based support during illness and childbirth. Nursing originated as an informal female practice, with women acting as family healers and paid wet nurses from antiquity, evolving into more structured attendant roles by the 18th and 19th centuries before formal training emerged.[26] Midwifery, a female-dominated field traceable to prehistoric eras and documented in records from 1600 BC, involved hands-on assistance in deliveries, herbal remedies, and postnatal care, often passed down through generations of women.[27] Until the late 19th century rise of male physicians, these practices relied on empirical knowledge accumulated over centuries, prioritizing maternal and infant welfare in ways that anticipated professional caregiving sectors.[28] Such occupations highlighted women's societal assignment to nurturing and service, driven by biological and cultural factors favoring female involvement in reproductive and health maintenance.Early 20th Century Innovations

The proliferation of office technologies in the early 20th century, such as typewriters and telephones, spurred the expansion of clerical roles predominantly filled by women. By 1900, women constituted about 19% of clerks in major U.S. cities like Chicago, but the introduction of these machines, which required dexterity and were marketed toward female typists and stenographers, accelerated feminization; telephone switchboards, staffed almost exclusively by women after the 1880s, saw massive growth with urban telephony expansion, employing over 200,000 "Hello Girls" by the 1910s.[29] Adding machines and filing systems further segmented office work, creating low-entry-barrier jobs that aligned with societal views of women's suitability for repetitive, detail-oriented tasks, leading to women comprising over 50% of clerical workers nationally by 1930.[30][31] Nursing underwent professionalization through institutional reforms, with the establishment of state registration laws beginning in 1903 when North Carolina enacted the first nurse practice act, requiring training and licensing to standardize care amid rising hospital demands from urbanization and medical advances.[32] The American Nurses Association, formalized in 1911 from earlier groups, advocated for education reforms, shifting from apprenticeship models to hospital-based diploma programs that enrolled thousands of women annually by the 1920s, emphasizing hygiene and patient care in response to public health crises like the 1918 influenza pandemic.[26] These changes elevated nursing from informal domestic work to a regulated occupation, though it remained low-paid and female-dominated, with over 90% of nurses being women by 1920.[33] Elementary teaching similarly formalized via normal schools and certification mandates, with women's share rising to 80-90% of public school teachers by 1910 due to expanded compulsory education laws and graded systems that favored female educators for younger grades.[34] Innovations like standardized curricula and urban school boards increased demand, employing women in roles seen as extensions of maternal duties, while high school graduation rates for women doubled from 1900 to 1930, supplying educated labor for these positions.[35] Between 1910 and 1930, clerical and professional service occupations (including teaching and nursing) saw the largest numerical gains for women, reflecting these structural shifts over manufacturing or agriculture.[36]World Wars and Workforce Expansion

During World War I, labor shortages in non-combat roles prompted significant female entry into service occupations such as nursing and clerical work. In the United States, over 10,000 nurses served near the Western Front in frontline medical stations, often without formal military rank or commission.[37] The American Red Cross expanded from 17,000 members to over 20 million, deploying 20,000 registered nurses to support war efforts.[38] In Britain, employers turned to women for clerical and commercial positions vacated by men, marking an early shift toward female dominance in administrative support.[39] This wartime necessity increased female labor force participation in these fields, with effects persisting into the interwar period due to male casualties.[40] World War II accelerated this trend on a larger scale, particularly in healthcare and administrative roles. The U.S. Army Nurse Corps and Navy Nurse Corps underwent dramatic growth to meet medical demands, with nurses serving in diverse theaters from Europe to the Pacific.[41] Approximately 350,000 American women joined the military, predominantly performing clerical duties and nursing rather than combat roles.[42] Overall, female employment in service-oriented jobs expanded as part of a broader influx, with about 5 million women entering the workforce between 1940 and 1945 to fill gaps in occupations like secretarial, telephone operation, and caregiving.[43] These roles, already female-dominated pre-war—such as nursing and midwifery, where over 90% of incumbents were women in 1940—saw reinforced segregation amid the labor crunch.[7] The wars thus catalyzed workforce expansion in pink-collar sectors by leveraging existing gender patterns in service work, though post-conflict policies often redirected women toward domesticity, limiting long-term gains in participation rates.[44] Government recruitment campaigns, including posters for nurse corps and civil service opportunities, underscored the targeted mobilization of women into these supportive positions.[45]Post-1945 Evolution and Term Coinage

Following World War II, the expansion of the U.S. service economy drove significant growth in female employment within traditionally feminine occupations, such as clerical work, retail sales, and caregiving roles, which became hallmarks of pink-collar labor. Despite societal pressures exemplified by campaigns urging women to vacate industrial jobs for domestic roles—evident in the reduction of female factory workers from 36% of the manufacturing workforce in 1944 to under 20% by 1947—many women persisted or transitioned into service-oriented positions. By 1950, women constituted approximately 29% of the total U.S. labor force, with over 40% of employed women in clerical or sales roles, reflecting the suburban boom and rising demand for administrative support in expanding bureaucracies and retail sectors.[34][46][7] This trend accelerated through the 1960s and 1970s amid broader economic shifts toward services, which accounted for 60% of U.S. GDP by 1970, up from 50% in 1947, pulling more married women into part-time or full-time pink-collar jobs to supplement household incomes amid stagnant real wages for male breadwinners. Female labor force participation rose to 43% by 1970, with pink-collar sectors absorbing the influx: secretaries and typists numbered over 3 million by 1960, predominantly women, while nursing employment grew from 500,000 in 1950 to 700,000 by 1970. These roles often featured low barriers to entry, flexible hours suiting family responsibilities, and cultural reinforcement of gender norms, yet they perpetuated occupational segregation, as women comprised 97% of telephone operators and 95% of private household workers in 1960.[34][11][7] The term "pink-collar worker" emerged in the late 1970s to denote these female-dominated service jobs, distinct from blue-collar manual labor or white-collar professions, and was popularized by journalist Louise Kapp Howe's 1977 book Pink Collar Workers: Inside the World of Women's Work, which drew on three years of fieldwork to highlight the undervalued nature of such employment.[47][48] Although some attribute an earlier sociological framing to economist William J. Baumol's 1960s analyses of service-sector productivity stagnation, the specific "pink-collar" phrasing gained traction during second-wave feminism to critique gender-based job ghettos amid rising awareness of wage disparities—pink-collar workers earned about 60% of male counterparts' pay in comparable roles by the late 1970s.[8]Predominant Occupations

Healthcare and Caregiving Roles

Healthcare and caregiving roles represent a core segment of pink-collar occupations, characterized by hands-on patient support and interpersonal care. These positions include registered nurses (RNs), who assess patient conditions, administer treatments, and coordinate care; licensed practical nurses (LPNs), who provide basic nursing under supervision; nursing assistants, who assist with daily living activities; and home health and personal care aides, who support individuals in residential settings.[49][50][51] Women dominate these fields, comprising 91% of RNs and 88% of the overall nursing workforce in the United States as of 2022.[52][53] In 2023, 87% of home health aides and 80% of personal care aides were women.[54] Broader data indicate women held 77.6% of jobs in health care and social assistance in 2021, totaling over 16 million positions.[55] These roles often require certifications or associate degrees rather than advanced professional training, aligning with pink-collar patterns of accessible entry for women.[51][50] Caregiving extends to informal and formal support for the elderly and disabled, where females constitute about 66% of caregivers.[56] Employment in these areas has grown rapidly, with projections for home health and personal care aides increasing 17% from 2024 to 2034, driven by aging populations.[49] Despite essential contributions to health systems, these jobs frequently involve physical demands, emotional labor, and shift work.[57]Education and Childcare Positions

Education and childcare positions, including elementary school teaching, preschool instruction, and daycare work, exemplify pink-collar occupations due to their emphasis on nurturing, interpersonal care, and routine service provision, with workforce compositions overwhelmingly female. In the United States, kindergarten and preschool teachers are 96.7% female, according to 2023 Bureau of Labor Statistics data analyzed in reports on occupational gender segregation.[58] Similarly, elementary and middle school teachers are approximately 79% female, reflecting patterns observed in 2022 labor force data from the BLS.[59] These roles typically require bachelor's degrees for certified teaching positions, though paraprofessional aides may enter with high school diplomas or associate degrees, facilitating accessibility for women balancing family responsibilities. Childcare workers, encompassing daycare providers, nannies, and early childhood assistants, exhibit even higher female predominance, with 92.4% of the approximately 702,687 employed in 2023 identifying as women.[60] The occupation involves daily tasks such as feeding, diapering, supervising play, and fostering basic developmental skills in children under age five, often in home-based or center settings regulated by state licensing. Employment in this sector totals around 497,450 workers, with median annual wages hovering near $32,000, underscoring the low-compensation nature of these service-oriented jobs.[61] Globally, preschool teaching staff reach 94% female representation, per UNESCO Institute for Statistics data, highlighting consistent gender patterns across contexts.[62] These positions demand emotional labor and flexibility, aligning with pink-collar traits of relational service over technical expertise, yet face high turnover due to physical demands and modest pay scales. In center-based early education, 98% of teaching staff are female, as documented in workforce indices from the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment.[63] Public school teaching extends this to broader K-12 levels, where women comprise 77% of educators overall, concentrated in lower grades requiring greater caregiving elements.[64] Such demographics persist despite efforts to diversify, rooted in occupational sorting by interpersonal skills traditionally associated with female socialization.Administrative and Clerical Work

Administrative and clerical occupations, including secretaries, administrative assistants, receptionists, and office clerks, primarily involve supporting executive functions through tasks such as document preparation, scheduling appointments, managing correspondence, data entry, and customer interactions. These roles demand organizational precision, communication skills, and routine administrative support, distinguishing them from higher-autonomy white-collar professions while aligning with pink-collar emphases on service-oriented labor.[65][8] In the United States, these positions remain heavily female-dominated, with 93 percent of administrative assistants identified as women in 2020 data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.[66] Earlier figures from 2017 similarly reported 94.7 percent of secretaries and administrative assistants as female, reflecting persistent gender segregation despite technological shifts like automation.[67] This predominance traces to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when mechanized office tools such as typewriters enabled women's entry into clerical work, as employers associated female dexterity and lower salary demands with suitability for repetitive, structured tasks.[68] By 1920, a majority of clerical workers in urban centers like Chicago were young, U.S.-born white women under age 24, often hired for their emerging high school education and perceived reliability in supportive roles.[69] Economically, these jobs offer median annual wages below national averages—for instance, secretaries and administrative assistants earned around $41,000 in 2023—while comprising about 2 percent of the total workforce, predominantly women facing limited upward mobility due to occupational crowding.[65][70] Despite projections of stable or minimal employment growth through 2034, driven by office consolidation and software efficiencies, the roles sustain pink-collar patterns through reliance on soft skills like empathy and multitasking, which empirical studies link to female labor preferences and socialization rather than solely structural barriers.[65][34]Service and Personal Care Jobs

Service and personal care jobs form a core segment of pink-collar occupations, encompassing roles that provide grooming, wellness, and assistive services directly to clients, such as hairdressers, cosmetologists, manicurists, skincare specialists, massage therapists, and personal care aides. These positions emphasize interpersonal engagement, manual dexterity, and customer-facing responsibilities, often in settings like salons, spas, or homes.[71][72] In recent data, these occupations exhibit strong female dominance. As of 2024, women constituted 91.3 percent of hairdressers, hairstylists, and cosmetologists, and 85.9 percent of manicurists and pedicurists in the United States. Personal care aides, who assist with non-medical daily living activities like bathing and dressing, were 80 percent female in 2023. Skincare specialists showed even higher disparity, with women comprising 98.2 percent in 2022 data. Overall, women represent 76.6 percent of first-line workers in personal care and service occupations.[73][54][59][74] Historically, such roles trace roots to pre-20th-century domestic service, where over 90 percent of workers were women in 1940, a pattern persisting in modern iterations despite some diversification. These jobs typically offer median wages below national averages—$37,000 annually for hairdressers in 2023—and face challenges like irregular hours and physical demands, yet they remain accessible with minimal formal education, often requiring vocational certification.[7][75]Economic Dimensions

Compensation Structures and Gaps

Pink-collar occupations typically feature compensation structures that blend hourly wages, salaried positions with step increases, and performance-based incentives, often supplemented by benefits like health insurance and pensions, particularly in public-sector roles such as teaching and nursing.[51] For instance, registered nurses frequently receive shift differentials and overtime pay due to irregular hours, while elementary school teachers operate under union-negotiated salary schedules tied to years of experience and education levels.[76] Administrative assistants and childcare workers, however, more commonly earn hourly wages with limited advancement ladders, reflecting the service-oriented nature of these jobs.[77] Median annual wages in these fields lag behind the national occupational median of $49,500 as of May 2024. Registered nurses earned a median of $93,600, exceeding the overall median but requiring advanced certification and facing high burnout rates.[51][78] Elementary school teachers averaged around $63,100 annually, with public-sector positions offering stability through tenure but constrained by fixed budgets.[79] Secretaries and administrative assistants received a median of $47,460, while childcare workers earned approximately $32,000 based on a $15.41 hourly median, often part-time or seasonal.[80][77] These figures reflect empirical patterns where female-dominated roles prioritize flexibility over premium pay, contributing to total compensation that includes non-wage elements like family leave but lower base earnings.[4] Wage gaps persist between pink-collar jobs and comparably skilled male-dominated fields, with studies indicating devaluation as occupations feminize: a 10 percentage point increase in female share correlates with 1-2% wage drops for all workers, net of skill requirements.[81][82] For example, care workers averaged $13.92 hourly in 2021, 20-30% below non-care occupations with similar education.[83] Explanations include supply gluts from gendered preferences for interpersonal work and family compatibility, alongside societal undervaluation of "nurturing" tasks, though causal evidence mixes norms with market dynamics like lower bargaining power in segregated fields.[84][4] Within pink-collar roles, gaps narrow due to homogeneity, but overall, women in these jobs earn 82-84% of male counterparts across sectors, amplified by occupational sorting rather than within-job discrimination alone.[21][85]Educational Barriers and Requirements

Pink-collar occupations generally demand postsecondary credentials rather than advanced degrees, with requirements varying by role. Registered nursing typically necessitates an associate degree in nursing (ADN) or a bachelor of science in nursing (BSN), plus licensure via the NCLEX-RN examination.[72] Elementary and secondary school teaching requires a bachelor's degree and state certification, often involving student teaching and pedagogy coursework.[8] Childcare workers may enter with a high school diploma and obtain the Child Development Associate (CDA) credential through assessed training, while administrative assistants often need only postsecondary certificates or associate degrees in office management.[86] These entry points reflect a balance of formal education and practical skills training, enabling quicker workforce integration compared to professions requiring graduate-level preparation. However, barriers persist in accessing such programs, particularly for women balancing familial obligations. Studies indicate familial responsibilities, including childcare, impede women's pursuit of specialized training or degree completion in caregiving fields.[87] Additionally, financial constraints affect low-income entrants, as certification costs and program tuition—averaging $10,000–$40,000 for nursing diplomas—can deter enrollment without employer sponsorship.[15] Despite women's overall higher educational attainment—comprising 50.7% of the U.S. college-educated labor force as of 2022—pink-collar workers frequently hold associate degrees or less, correlating with occupational segregation patterns.[88] This suggests that while barriers like program waitlists and geographic access to vocational schools exist, self-selection driven by preferences for flexible, interpersonal roles influences educational paths over insurmountable obstacles.[89] Empirical data from labor statistics show that non-college women in these sectors face fewer formal hurdles to entry than in male-dominated trades, though upward mobility to supervisory roles demands further credentials amid persistent gender gaps in promotion.[90]Occupational Segregation Data

In the United States, occupational segregation by gender persists despite declines over decades, as measured by the Duncan segregation index, which quantifies the proportion of workers who would need to change occupations for perfect gender integration. The index fell from approximately 0.68 in 1972 to 0.50 in 2011, with limited further progress by the 2020s, indicating that gender distributions remain uneven across fields.[91] This segregation is evident in pink-collar occupations, where women constitute the vast majority of workers, reflecting concentrations in service, caregiving, and administrative roles rather than uniform distribution proportional to their 47% share of the overall labor force.[92] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data from 2023 highlight stark gender imbalances in key pink-collar sectors. In healthcare, women comprise about 88% of registered nurses, with men at roughly 12%, a figure consistent across licensed practical nurses and related roles.[93] In education, women hold 77% of public school teaching positions as of 2020–21 data extended into recent trends, rising to 89% for elementary school teachers and 96.7% for kindergarten and preschool teachers.[64] [58] Administrative roles show similar patterns, with women at 94% of secretaries and administrative assistants, including 96.4% of legal secretaries.[70] [94] The following table summarizes gender distributions in select pink-collar occupations based on recent federal data:| Occupation | Percent Women | Year | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Registered Nurses | 88% | 2023 | BLS |

| Elementary School Teachers | 89% | 2023 | NCES/BLS |

| Kindergarten Teachers | 96.7% | 2023 | BLS |

| Secretaries/Administrative Assistants | 94% | 2022 | Census/BLS |

| Childcare Workers | 94% | 2023 | BLS (inferred from trends) |