Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chromosome abnormality

View on Wikipedia

A chromosomal abnormality or chromosomal anomaly is a missing, extra, or irregular portion of chromosomal DNA.[1][2] These can occur in the form of numerical abnormalities, where there is an atypical number of chromosomes, or as structural abnormalities, where one or more individual chromosomes are altered. Chromosome mutation was formerly used in a strict sense to mean a change in a chromosomal segment, involving more than one gene.[3] Chromosome anomalies usually occur when there is an error in cell division following meiosis or mitosis. Chromosome abnormalities may be detected or confirmed by comparing an individual's karyotype, or full set of chromosomes, to a typical karyotype for the species via genetic testing.

Sometimes chromosomal abnormalities arise in the early stages of an embryo, sperm, or infant.[4] They can be caused by various environmental factors. The implications of chromosomal abnormalities depend on the specific problem, they may have quite different ramifications.[citation needed] Diseases and conditions caused by chromosomal abnormalities are called chromosomal disorders or chromosomal aberrations.[5] Some examples are Down syndrome and Turner syndrome. However, chromosomal abnormalities do not always lead to diseases. Among abnormalities, structural rearrangements of genes between chromosomes can be harmless if they are balanced, which means that a set of the chromosomes remains complete and there are no gene breaks across the chromosomes.[6]

Numerical abnormality

[edit]

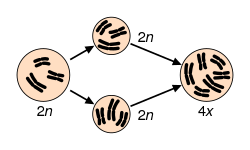

Maintaining a euploid state, where cells contain the correct number of chromosome sets, is essential for genomic stability.[7] Aneuploidy, characterized by an abnormal number of chromosomes, occurs when an individual is missing a chromosome from a pair (monosomy) or has an additional chromosome (trisomy).[8][9][10] This may be either full, involving a whole chromosome, or partial, where only part of a chromosome is missing or added.[8][9][10] Aneuploidy may arise from meiosis segregation errors such as nondisjunction, premature disjunction, or anaphase lag during meiosis I or II.[11] For aneuploidy, nondisjunction, the most frequent error, particularly in oocyte formation, occurs when replicated chromosomes fail to separate properly, leading to germ cells with an extra or missing chromosome.[11] Additionally, polyploidy occurs when cells contain more than two sets of chromosomes.[12] Polyploidy encompasses various forms, including triploid (three sets of chromosomes) and tetraploid (four sets of chromosomes).[7] Tetraploidy often arises from developmental errors during mitosis, such as cytokinesis failure, endoreplication, mitotic slippage, and cell fusion. These errors can subsequently lead to aneuploidy.[7]

Aneuploidy can occur with sex chromosomes or autosomes.[13] Rather than having monosomy, or only one copy, the majority of aneuploid people have trisomy, or three copies of one chromosome.[1] An example of trisomy in humans is Down syndrome, which is a developmental disorder caused by an extra copy of chromosome 21; the disorder is therefore also called "trisomy 21".[14] An example of monosomy in humans is Turner syndrome, where the individual is born with only one sex chromosome, an X.[15]

Sperm aneuploidy

[edit]Exposure of males to certain lifestyle, environmental and/or occupational hazards may increase the risk of aneuploid spermatozoa.[16] In particular, risk of aneuploidy is increased by tobacco smoking,[17][18] and occupational exposure to benzene,[19] insecticides,[20][21] and perfluorinated compounds.[22] Increased aneuploidy is often associated with increased DNA damage in spermatozoa.

Structural abnormalities

[edit]

Structural abnormalities in chromosomes may result from breakage and improper realignment of chromosome segments.[1] When the structure of a chromosome is altered, it can result in unbalanced rearrangements, balanced rearrangements, ring chromosomes, and isochromosomes.[1][23] To expand, these abnormalities may be defined as follows: [1][23]

- Unbalanced rearrangements includes missing or additional genetic information in chromosomes.[1] They include:

- Deletions: A portion of the chromosome is missing or has been deleted.[1]Known disorders in humans include Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome, which is caused by partial deletion of the short arm of chromosome 4; and Jacobsen syndrome, also called the terminal 11q deletion disorder.[23]

- Duplications: A portion of the chromosome has been duplicated, resulting in extra genetic material.[1] Known human disorders include Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 1A, which may be caused by duplication of the gene encoding peripheral myelin protein 22 (PMP22) on chromosome 17.[23]

- Insertions: A portion of one chromosome has been deleted from its normal place and inserted into another chromosome.[1]

- Balanced rearrangements includes the alteration of chromosome segments but the genetic information is not lost or gained.[1] They include:

- Inversions: A portion of the chromosome has broken off, turned upside down, and reattached, therefore the genetic material is inverted.[1]

- Translocations: A portion of one chromosome has been transferred to another chromosome.[1] There are two main types of translocations:

- Reciprocal translocation: Segments from two different chromosomes have been exchanged.[23]

- Robertsonian translocation: A pair of chromosomes break at their centromeres, lose their short p arms, and fuse at their q arms, forming a single chromosome with one centromere.[1] This type of translocation typically occurs between chromosomes 13, 14, 15, 21, and 22 in humans.[23]

- Rings: A portion of a chromosome (the ends) has broken off and formed a circle or ring. This happens with or without the loss of genetic material.[1]

- Isochromosome: Formed by the mirror image copy of a chromosome segment including the centromere.[23] Specifically, they form when one arm of a chromosome is lost, and the remaining arm duplicates.[1]

Chromosome instability syndromes are a group of disorders characterized by chromosomal instability and breakage. They often lead to an increased tendency to develop certain types of malignancies.[24]

Inheritance

[edit]

Constitutional chromosome abnormalities (present at beginning of development) arise during gametogenesis or embryogenesis, affecting a significant proportion of an organism's cells.[25] These inherited abnormalities most commonly occur as errors in the egg or sperm, meaning the anomaly is present in every cell of the body.[1] Factors such as maternal age and environmental influences contribute to the occurrence of these genetic errors.[1] Offspring inherit two copies of each gene, one from each parent, and mutations (often caused by disease) may be passed down through generations.[26] The diseases that follow a single-gene inheritance pattern are relatively rare but affect millions of individuals.[26] This can be represented through the Mendelian inheritance patterns: [26][27]

- Autosomal dominant: Where at least one affected parent passes the mutation, and the condition appears in every generation.[26] Examples include Huntington's disease, achondroplasia, and neurofibromatosis.[26]

- Autosomal recessive: Both parents are carriers of the mutation (though it may not appear in every generation). The disorder manifests only when both copies of the inherited gene are mutated.[26] Examples include tay-Sachs disease, sickle cell anemia, and cystic fibrosis.[26]

- X-linked inheritance: Mutated X chromosomes may be inherited in a dominant or recessive manner. Within X-linked recessive inheritance, males are more frequently affected than females. Since males have only one X chromosome, they will express the disease if that single X carries the mutation. Examples include hemophilia and fabry disease.[27] In contrast, females, with two X chromosomes, must inherit the mutated gene from both parents for the disorder to manifest. X-linked dominant diseases can affect both males and females. A father with an X-linked dominant trait may only pass it to his daughters, while a mother can pass the trait to both sons and daughters. An example of this is incontinentia pigmenti.[27]

- Mitochondrial inheritance: This pattern affects both males and females but is inherited and passed only through the mother.[26] Examples include Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy and Kearns-Sayre syndrome.[26]

Given these patterns of inheritance, chromosome studies are often conducted on parents when a child is found to have a chromosomal anomaly. If the parents do not exhibit the abnormality, it was not inherited but may be passed down in subsequent generations.[28]

Chromosomal abnormalities can also arise from de novo mutations within an individual.[29] De novo mutations are spontaneous, somatic mutations that occur without prior inheritance, and they can emerge at various stages of life, including during the parental germline, embryonic or fetal development, or later in life due to aging.[30] These mutations may occur during gametogenesis or postzygotically, resulting in new mutations that appear in a single generation without prior evidence of mutation in the parental chromosomes.[31] Approximately 7% of de novo mutations are present as high-level mosaic mutations.[31] Genetic mosaicism, which refers to a post-zygotic mutation, occurs when an individual possesses two or more genetically distinct cell populations derived from a single fertilized egg.[11][31] This can lead to chromosomal abnormalities, and these mutations may be present in somatic cells, germ cells, or both, in the case of gonosomal mosaicism, where mutations exist in both somatic and germline cells.[30] Somatic mosaicism involves multiple cell lineages in somatic cells, while germline mosaicism occurs in multiple lineages within germline cells, allowing the mutation to be passed to offspring.[11] An example of a chromosomal abnormality resulting from genetic mosaicism is Turner syndrome.[11]

Acquired chromosome abnormalities

[edit]Acquired chromosomal abnormalities represent genetic alterations that manifest during an individual's lifetime, as opposed to being inherited from their parents.[25] These modifications predominantly occur within somatic cells and are characterized by their non-heritable nature.[25] Typically, they arise from mutations that transpire during the process of DNA replication or as a consequence of exposure to various environmental factors.[32] In contrast to constitutional chromosomal abnormalities, which are present at birth, acquired abnormalities occur during adulthood and are confined to specific clones of cells, thereby inhibiting their distribution throughout the body.[32]

The development of chromosomal abnormalities and malignancies can be attributed to environmental exposures or may occur spontaneously during DNA replication.[32][33] Spontaneous replication errors typically occur due to DNA polymerase synthesizing new polynucleotides while evading proofreading functions, leading to mismatches in base pairing.[33] Throughout a human's lifetime, individuals may encounter mutagens (which are agents that induce mutations) that lead to chromosomal mutations. These mutations arise when a mutagen interacts with parental DNA, typically affecting one strand, resulting in structural alterations that hinder the successful base pairing with the modified nucleotide.[33] Consequently, daughter molecules inherit these mutations, which may further accumulate additional damage, subsequently being passed down to the next generations of cells.[34] Mutagens can be classified as physical, chemical, or biological:

- Chemical: Common chemical mutagens include base analogs (molecules that resemble nitrogenous bases), deaminating agents (which remove amino groups), alkylating agents, and intercalating agents.[33]

- Physical: The most prevalent sources of physical mutagens are exposure to UV radiation, which induces dimerization of adjacent pyrimidine bases, and ionizing radiation, which typically causes point mutations, insertions, or deletions.[33] Heat can also function as a mutagen by promoting the cleavage of the β-N-glycosidic bond, which connects the base to the sugar part of the nucleotide, through water-induced processes.[33]

- Biological: Biological mutagens are introduced through exposure to viruses, bacteria, and/or transposons and insertion sequences (IS).[35] Transposons and IS can move through DNA by 'jumping,' disrupting the functionality of chromosomal DNA. The insertion of viral DNA can lead to genetic disruption, while bacteria may produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) that cause inflammation and DNA damage, resulting in decreased repair efficiency.[35]

Sporadic cancers are those that develop due to mutations that are not inherited; in these cases, normal cells gradually accumulate mutations and cellular damage.[34] Most cancers, if not all, could cause chromosome abnormalities,[36] with either the formation of hybrid genes and fusion proteins, deregulation of genes and overexpression of proteins, or loss of tumor suppressor genes (see the "Mitelman Database" [37] and the Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology,[38]). Approximately 90% of cancers exhibit chromosomal instability (CIN), characterized by the frequent gain or loss of entire chromosome segments.[39] This phenomenon contributes to tumor aneuploidy and intra-tumor heterogeneity, which are commonly observed in most human cancers.[32][39] For instance, certain consistent chromosomal abnormalities can turn normal cells into a leukemic cell such as the translocation of a gene, resulting in its inappropriate expression.[40]

DNA damage during spermatogenesis

[edit]DNA damage during spermatogenesis plays a crucial role in chromosomal abnormalities and male fertility. In the early stages of sperm development, DNA repair mechanisms such as homologous recombination (HR) and mismatch repair (MMR) efficiently correct replication errors and double-strand breaks (DSBs).[41][42] However, as spermatogenesis progresses, DNA repair capacity declines due to changes in how DNA is packaged inside sperm cells.

Spermatogenesis occurs in three phases: mitosis (spermatocytogenesis), meiosis, and spermiogenesis. During spermiogenesis, the DNA becomes more tightly packed to fit inside the sperm head.[43] This happens because histone proteins, which normally help organize DNA, are replaced with transition proteins (TNP1, TNP2) and then protamines (PRM1, PRM2). While this packaging protects the DNA, it also makes it harder for repair enzymes to fix any damage.[44] As a result, non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), an error-prone repair process, becomes the main repair mechanism, increasing the risk of mutations.

Oxidative stress is another major factor contributing to DNA damage in sperm cells. Reactive oxygen species (ROS), produced both inside sperm and from external sources such as immune cells in seminal fluid, can break DNA strands. High ROS levels can overwhelm antioxidant defences, leading to further damage and triggering cell death pathways.[45]

Normally, defective sperm cells are removed through apoptosis, a controlled cell death process. However, if this system fails—such as when there is an imbalance between pro-apoptotic (BAX) and anti-apoptotic (BCL-2) factors—damaged sperm may survive.[46] If these sperm fertilize an egg, the oocyte's repair mechanisms may attempt to fix the damage.[47]

The maternal repair machinery is capable of correcting sperm DNA damage post-fertilization, but errors in this process can result in chromosomal structural aberrations in the developing zygote.[48] Notably, exposure to DNA-damaging agents, such as the chemotherapy drug Melphalan, can induce inter-strand DNA crosslinks that escape paternal repair, potentially leading to chromosomal abnormalities due to maternal misrepair. Therefore, both pre- and post-fertilization DNA repair are crucial for maintaining genome integrity and preventing genetic defects in the offspring.[49]

DNA damage in sperm has been linked to infertility, increased miscarriage risk, and conditions such as aneuploidy and structural chromosomal rearrangements. Understanding how DNA damage occurs and is repaired during spermatogenesis is important for studying male reproductive health and genetic inheritance.[50]

Detection

[edit]Chromosomal abnormalities can be detected at either postnatal testing or prenatal screening, which includes prenatal diagnosis.[51] Early detection is crucial for enabling parents to assess their upcoming pregnancy options.[52]

Common techniques used to detect diseases resulting from chromosomal abnormalities:

Karyotyping has been the traditional method used to detect chromosomal abnormalities. It requires entire set of chromosomes to be able to identify fetal aneuploidy and variations in structural arrangements, which could be a result of insertions, inversions, duplications or deletions of chromosomes.[11] The samples used to obtain results from fetal karyotyping can be acquired through various sampling techniques. Amongst the aneuploidy testings, those which use amniotic fluid is preferred due its benefit of having high sensitivity with relatively low risks.[52]

For increased resolution of screening, Chromosomal Microarray Analysis (CMA) can be used which is based on comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) to identify copy number variations (CNVs). This alternative method to karyotyping reduces result uncertainty through its use of invasive fetal cell collection technique.[52]

FISH technique detects chromosomal abnormalities through labeling of the chromosome by fluorescence using specialized probes. It is important that these probes are validated before use as they are carefully regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[52]

FISH is a technique used for the treatment of specific cases such as Multiple myeloma (MM) and can be used to analyze bone marrow samples to identify changes in chromosomes at a single-cell level.[53] For the treatment of MM relapse, acquired chromosomal abnormalities such as del (17p), amp (1q) and Tetraploidy can be analyzed to guide future therapy development and updated prognosis.[53]

Spectral Karyotyping (SKY) is a recent technology developed from the FISH technique that colors each human chromosome in a different color for identification in analysis.[54] Through the use of fluorescent dyes such as Cy5, Texas red and spectrum green, 24 distinguishable colors can be generated using imaging spectroscopy.[54]

Depending on the information one wants to obtain, different techniques and samples are needed.[citation needed]

- For the prenatal diagnosis of a fetus, amniocentesis, chorionic villus sampling, or circulating foetal cells would be collected and analysed in order to detect possible chromosomal abnormalities.

- For the preimplantational diagnosis of an embryo, a blastocyst biopsy would be performed.

- For a lymphoma or leukemia screening the technique used would be a bone marrow biopsy.

Nomenclature

[edit]-

Three chromosomal abnormalities with ISCN nomenclature, with increasing complexity: (A) A tumour karyotype in a male with loss of the Y chromosome, (B) Prader–Willi Syndrome i.e. deletion in the 15q11-q12 region and (C) an arbitrary karyotype that involves a variety of autosomal and allosomal abnormalities.[55]

-

Human karyotype with annotated bands and sub-bands as used for the nomenclature of chromosome abnormalities. It shows dark and white regions as seen on G banding. Each row is vertically aligned at centromere level. It shows 22 homologous autosomal chromosome pairs, both the female (XX) and male (XY) versions of the two sex chromosomes, as well as the mitochondrial genome (at bottom left).

The International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature (ISCN) is an international standard for human chromosome nomenclature, which includes band names, symbols and abbreviated terms used in the description of human chromosome and chromosome abnormalities. Abbreviations include a minus sign (-) for chromosome deletions, and del for deletions of parts of a chromosome.[56]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Chromosomal Abnormalities". Understanding Genetics: A New York, Mid-Atlantic Guide for Patients and Health Professionals. Genetic Alliance. 2009-07-08. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ "Chromosome Abnormalities Fact Sheet". NHGRI. 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-09-25.

- ^ Rieger R, Michaelis A, Green M (1968). "Mutation". A glossary of genetics and cytogenetics: Classical and molecular. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-07668-3.

- ^ Chen H (2006). Atlas of genetic diagnosis and counseling. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press. ISBN 978-1-58829-681-8.

- ^ Manglik MR (2024-04-24). Veterinary General Pathology. EduGorilla Publication. p. 529. ISBN 978-93-7115-241-9.

- ^ Genetic Alliance (2008). Understanding Genetics: A New York, Mid-Atlantic Guide for Patients and Health Professionals (PDF). Genetic Alliance. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-9821622-1-7. Wikidata Q136041435.

- ^ a b c Orr B, Godek KM, Compton D (June 2015). "Aneuploidy". Current Biology. 25 (13): R538 – R542. Bibcode:2015CBio...25.R538O. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.05.010. PMC 4714037. PMID 26126276.

- ^ a b Chromosome abnormalities and genetic counseling | WorldCat.org. OCLC 769344040.

- ^ a b "Content - Health Encyclopedia - University of Rochester Medical Center". www.urmc.rochester.edu. Retrieved 2025-04-03.

- ^ a b Gardner RJ, Sutherland GR, Shaffer LG (2012). Chromosome abnormalities and genetic counseling (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974915-7. OCLC 769344040.

- ^ a b c d e f Queremel Milani DA, Tadi P (2025). "Genetics, Chromosome Abnormalities". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32491623. Retrieved 2025-04-03.

- ^ Potapova T, Gorbsky GJ (February 2017). "The Consequences of Chromosome Segregation Errors in Mitosis and Meiosis". Biology. 6 (1): 12. doi:10.3390/biology6010012. PMC 5372005. PMID 28208750.

- ^ "Chromosomal Abnormalities: Aneuploidies | Learn Science at Scitable". www.nature.com. Retrieved 2025-04-04.

- ^ Patterson D (July 2009). "Molecular genetic analysis of Down syndrome". Human Genetics. 126 (1): 195–214. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0696-8. PMID 19526251. S2CID 10403507.

- ^ "Turner Syndrome". National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- ^ Templado C, Uroz L, Estop A (October 2013). "New insights on the origin and relevance of aneuploidy in human spermatozoa". Molecular Human Reproduction. 19 (10): 634–643. doi:10.1093/molehr/gat039. PMID 23720770.

- ^ Shi Q, Ko E, Barclay L, Hoang T, Rademaker A, Martin R (August 2001). "Cigarette smoking and aneuploidy in human sperm". Molecular Reproduction and Development. 59 (4): 417–421. doi:10.1002/mrd.1048. PMID 11468778. S2CID 35230655.

- ^ Rubes J, Lowe X, Moore D, Perreault S, Slott V, Evenson D, et al. (October 1998). "Smoking cigarettes is associated with increased sperm disomy in teenage men". Fertility and Sterility. 70 (4): 715–723. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00261-1. PMID 9797104.

- ^ Xing C, Marchetti F, Li G, Weldon RH, Kurtovich E, Young S, et al. (June 2010). "Benzene exposure near the U.S. permissible limit is associated with sperm aneuploidy". Environmental Health Perspectives. 118 (6): 833–839. Bibcode:2010EnvHP.118..833X. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901531. PMC 2898861. PMID 20418200.

- ^ Xia Y, Bian Q, Xu L, Cheng S, Song L, Liu J, et al. (October 2004). "Genotoxic effects on human spermatozoa among pesticide factory workers exposed to fenvalerate". Toxicology. 203 (1–3): 49–60. Bibcode:2004Toxgy.203...49X. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2004.05.018. PMID 15363581. S2CID 36073841.

- ^ Xia Y, Cheng S, Bian Q, Xu L, Collins MD, Chang HC, et al. (May 2005). "Genotoxic effects on spermatozoa of carbaryl-exposed workers". Toxicological Sciences. 85 (1): 615–623. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfi066. PMID 15615886.

- ^ Governini L, Guerranti C, De Leo V, Boschi L, Luddi A, Gori M, et al. (November 2015). "Chromosomal aneuploidies and DNA fragmentation of human spermatozoa from patients exposed to perfluorinated compounds". Andrologia. 47 (9): 1012–1019. doi:10.1111/and.12371. hdl:11365/982323. PMID 25382683. S2CID 13484513.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Chromosome Abnormalities". atlasgeneticsoncology.org. Archived from the original on 14 August 2006. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Rayi A, Hozayen A (2025). "Chromosome Instability Syndromes". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30725883. Retrieved 2025-04-04.

- ^ a b c McFadden DE, Friedman JM (December 1997). "Chromosome abnormalities in human beings". Mutation Research. 396 (1–2): 129–140. Bibcode:1997MRFMM.396..129M. doi:10.1016/S0027-5107(97)00179-6. PMID 9434864.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Genetic Alliance, The New York-Mid-Atlantic Consortium for Genetic and Newborn Screening Services (July 2009). "APPENDIX E, INHERITANCE PATTERNS". Understanding Genetics: A New York, Mid-Atlantic Guide for Patients and Health Professionals. Washington (DC): Genetic Alliance.

- ^ a b c Basta M, Pandya AM (2025). "Genetics, X-Linked Inheritance". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32491315. Retrieved 2025-04-05.

- ^ "Genetic Testing (for Parents)". kidshealth.org. Retrieved 2025-04-05.

- ^ Liu Y, Shen J, Yang R, Zhang Y, Jia L, Guan Y (2022-03-19). Bevilacqua A (ed.). "The Relationship between Human Embryo Parameters and De Novo Chromosomal Abnormalities in Preimplantation Genetic Testing Cycles". International Journal of Endocrinology. 2022 9707081. doi:10.1155/2022/9707081. PMC 8957472. PMID 35345425.

- ^ a b Mohiuddin M, Kooy RF, Pearson CE (2022-09-26). "De novo mutations, genetic mosaicism and human disease". Frontiers in Genetics. 13 983668. doi:10.3389/fgene.2022.983668. PMC 9550265. PMID 36226191.

- ^ a b c Acuna-Hidalgo R, Veltman JA, Hoischen A (November 2016). "New insights into the generation and role of de novo mutations in health and disease". Genome Biology. 17 (1) 241. doi:10.1186/s13059-016-1110-1. PMC 5125044. PMID 27894357.

- ^ a b c d McGranahan N, Burrell RA, Endesfelder D, Novelli MR, Swanton C (June 2012). "Cancer chromosomal instability: therapeutic and diagnostic challenges". EMBO Reports. 13 (6): 528–538. doi:10.1038/embor.2012.61. PMC 3367245. PMID 22595889.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown TA (2002). "Mutation, Repair and Recombination". Genomes (2nd ed.). Wiley-Liss. Retrieved 2025-03-31.

- ^ a b "Inherited Mutations and Cancer". Inherited Mutations and Cancer. Retrieved 2025-03-31.

- ^ a b Kapali D (2023-08-03). "Mutagens- Definition, Types (Physical, Chemical, Biological)". microbenotes.com. Retrieved 2025-03-31.

- ^ "Chromosomes, Leukemias, Solid Tumors, Hereditary Cancers". atlasgeneticsoncology.org. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ "Mitelman Database of Chromosome Aberrations and Gene Fusions in Cancer". Archived from the original on 2016-05-29.

- ^ "Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology". atlasgeneticsoncology.org. Archived from the original on 2011-02-23.

- ^ a b Kou F, Wu L, Ren X, Yang L (June 2020). "Chromosome Abnormalities: New Insights into Their Clinical Significance in Cancer". Molecular Therapy Oncolytics. 17: 562–570. doi:10.1016/j.omto.2020.05.010. PMC 7321812. PMID 32637574.

- ^ Chaganti RS, Nanjangud G, Schmidt H, Teruya-Feldstein J (October 2000). "Recurring chromosomal abnormalities in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: biologic and clinical significance". Seminars in Hematology. 37 (4): 396–411. doi:10.1016/s0037-1963(00)90019-2. PMID 11071361.

- ^ Baarends W (2001-01-01). "DNA repair mechanisms and gametogenesis". Reproduction. 121 (1): 31–39. doi:10.1530/reprod/121.1.31. hdl:1765/9599. ISSN 1470-1626.

- ^ Talibova G, Bilmez Y, Ozturk S (October 2022). "DNA double-strand break repair in male germ cells during spermatogenesis and its association with male infertility development". DNA Repair. 118 103386. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2022.103386. PMID 35963140.

- ^ Marchetti F, Bishop J, Gingerich J, Wyrobek AJ (January 2015). "Meiotic interstrand DNA damage escapes paternal repair and causes chromosomal aberrations in the zygote by maternal misrepair". Scientific Reports. 5 (1) 7689. Bibcode:2015NatSR...5.7689M. doi:10.1038/srep07689. PMC 4286742. PMID 25567288.

- ^ Cao Y, Wang S, Qin Z, Xiong Q, Liu J, Li W, et al. (February 2025). "Male germ cells with Bag5 deficiency show reduced spermiogenesis and exchange of basic nuclear proteins". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 82 (1) 92. doi:10.1007/s00018-025-05591-2. PMC 11850669. PMID 39992433.

- ^ Wang Y, Fu X, Li H (2025-02-05). "Mechanisms of oxidative stress-induced sperm dysfunction". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 16 1520835. doi:10.3389/fendo.2025.1520835. PMC 11835670. PMID 39974821.

- ^ Sharma P, Kaushal N, Saleth LR, Ghavami S, Dhingra S, Kaur P (August 2023). "Oxidative stress-induced apoptosis and autophagy: Balancing the contrary forces in spermatogenesis". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 1869 (6) 166742. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2023.166742. PMID 37146914.

- ^ Li N, Wang H, Zou S, Yu X, Li J (January 2025). "Perspective in the Mechanisms for Repairing Sperm DNA Damage". Reproductive Sciences. 32 (1): 41–51. doi:10.1007/s43032-024-01714-5. PMC 11729216. PMID 39333437.

- ^ Marchetti F, Essers J, Kanaar R, Wyrobek AJ (November 2007). "Disruption of maternal DNA repair increases sperm-derived chromosomal aberrations". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (45): 17725–17729. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10417725M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0705257104. PMC 2077046. PMID 17978187.

- ^ Deans AJ, West SC (June 2011). "DNA interstrand crosslink repair and cancer". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 11 (7): 467–480. doi:10.1038/nrc3088. PMC 3560328. PMID 21701511.

- ^ Zini A, Libman J (August 2006). "Sperm DNA damage: clinical significance in the era of assisted reproduction". CMAJ. 175 (5): 495–500. doi:10.1503/cmaj.060218. PMC 1550758. PMID 16940270.

- ^ Fonda Allen J, Stoll K, Bernhardt BA (February 2016). "Pre- and post-test genetic counseling for chromosomal and Mendelian disorders". Seminars in Perinatology. The Changing Paradigm of Perinatal screening for Birth Defects. 40 (1): 44–55. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2015.11.007. PMC 4826755. PMID 26718445.

- ^ a b c d Hixson L, Goel S, Schuber P, Faltas V, Lee J, Narayakkadan A, et al. (October 2015). "An Overview on Prenatal Screening for Chromosomal Aberrations". Journal of Laboratory Automation. 20 (5): 562–573. doi:10.1177/2211068214564595. PMID 25587000.

- ^ a b Locher M, Jukic E, Vogi V, Keller MA, Kröll T, Schwendinger S, et al. (March 2023). "Amp(1q) and tetraploidy are commonly acquired chromosomal abnormalities in relapsed multiple myeloma". European Journal of Haematology. 110 (3): 296–304. doi:10.1111/ejh.13905. PMC 10107198. PMID 36433728.

- ^ a b Imataka G, Arisaka O (January 2012). "Chromosome analysis using spectral karyotyping (SKY)". Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 62 (1): 13–17. doi:10.1007/s12013-011-9285-2. PMC 3254861. PMID 21948110.

- ^ Warrender JD, Moorman AV, Lord P (December 2019). "A fully computational and reasonable representation for karyotypes". Bioinformatics. 35 (24): 5264–5270. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btz440. PMC 6954653. PMID 31228194.

- "This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)" - ^ "ISCN Symbols and Abbreviated Terms". Coriell Institute for Medical Research. Retrieved 2022-10-27.

External links

[edit]- Chromosome+disorders at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

Chromosome abnormality

View on GrokipediaTypes of Chromosome Abnormalities

Numerical Abnormalities

Numerical abnormalities refer to deviations in the total number of chromosomes from the normal diploid complement of 46 in humans, encompassing conditions where cells have an abnormal count of whole chromosomes. These abnormalities are broadly classified into aneuploidy, which involves gains or losses of specific chromosomes, and polyploidy, which features extra complete sets of chromosomes. Such changes typically arise during cell division and can lead to significant genetic imbalances in affected individuals.[1] Aneuploidy represents the most common form of numerical abnormality, characterized by the presence of an abnormal number of chromosomes in otherwise diploid cells, such as 45 or 47 chromosomes instead of 46. Subtypes include monosomy, where one chromosome is missing (resulting in 45 chromosomes, denoted as 2N-1), and trisomy, where one chromosome is present in three copies (resulting in 47 chromosomes, denoted as 2N+1). Rarer variants encompass tetrasomy (four copies of a chromosome, 2N+2) and nullisomy (complete loss of a chromosome pair, 2N-2), though these are exceptionally uncommon due to their severe genetic disruptions.[1][4] The primary mechanism underlying numerical abnormalities is nondisjunction, an error in chromosome segregation during cell division. In meiosis, which occurs in gamete formation, homologous chromosomes or sister chromatids fail to separate properly, producing gametes with extra or missing chromosomes that, upon fertilization, form aneuploid zygotes. Nondisjunction can also occur during mitosis in early embryonic development, leading to mosaic aneuploidy where only some cells are affected. These errors are more frequent in meiosis I of oogenesis and increase with maternal age due to aging oocytes.[5][4] A well-known example of trisomy is trisomy 21, where three copies of chromosome 21 result in 47 chromosomes, illustrating how a single extra chromosome can alter gene dosage. Polyploidy, in contrast, involves entire extra sets, such as triploidy (3N, 69 chromosomes) or tetraploidy (4N, 92 chromosomes), often arising from fertilization of an egg by two sperm or failure of cytokinesis. These conditions are rare in viable human pregnancies, as polyploid embryos typically fail to develop beyond early stages and are incompatible with life.[1] Numerical abnormalities affect approximately 5-10% of all recognized pregnancies, with the vast majority being non-viable and resulting in spontaneous miscarriage; only a small fraction, around 0.4-0.9% of live births, involve surviving cases like certain aneuploidies.[1]Structural Abnormalities

Structural abnormalities of chromosomes are alterations in the physical structure or morphology of one or more chromosomes, resulting from breaks, rearrangements, or losses and gains of genetic segments, without a change in the overall chromosome number.[1] These changes disrupt the normal arrangement of genetic material and can lead to various health effects depending on the extent of imbalance.[6] The main types of structural abnormalities include deletions, duplications, inversions, translocations, insertions, isochromosomes, and ring chromosomes. Deletions involve the loss of a chromosome segment, potentially causing conditions like cri-du-chat syndrome when occurring on the short arm of chromosome 5.[1] Duplications result in an extra copy of a segment, leading to gene dosage imbalances. Inversions occur when a segment breaks, rotates 180 degrees, and rejoins, classified as paracentric (not involving the centromere) or pericentric (involving the centromere). Translocations involve the exchange of segments between non-homologous chromosomes and can be balanced (no net loss or gain of material) or unbalanced (resulting in partial monosomy or trisomy). Insertions occur when a segment from one chromosome is inserted into another, often non-homologous, chromosome. Isochromosomes form when one chromosome arm is duplicated and the other lost, creating mirror-image arms. Ring chromosomes arise when both ends of a chromosome break and fuse into a circle, typically with loss of terminal material.[1][6][3] These abnormalities typically form through chromosome breakage followed by faulty repair mechanisms. Breakage can be induced by external factors such as ionizing radiation or chemical mutagens, or by internal errors during DNA replication or cell division. The repair process, involving enzymes like DNA ligases, may misjoin broken ends, leading to rearrangements; unequal crossing over during meiosis can also contribute. Balanced structural abnormalities do not alter the total genetic content and often have no phenotypic effects in carriers, though they may cause issues in offspring if gametes receive unbalanced segments. In contrast, unbalanced abnormalities result in net gain or loss of genetic material, frequently causing developmental disorders or miscarriage due to gene dosage effects.[1][7][3] Structural chromosome abnormalities are observed in approximately 0.5-1% of live births, though exact rates vary by population and detection method; they are more prevalent in miscarriages, accounting for a significant portion of pregnancy losses where chromosomal issues are involved.[1][4] Cryptic rearrangements, which are subtle structural changes not visible under standard microscopy, can only be detected using advanced molecular techniques like fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH).[1]Causes and Mechanisms

Inherited Abnormalities

Inherited chromosome abnormalities are constitutional changes that originate in the germline cells of parents and are transmitted to offspring via gametes, resulting in their presence in the zygote and most cells of the developing embryo.[1] These differ from de novo abnormalities, which arise spontaneously during gametogenesis or early embryogenesis in the affected individual without parental origin.[1] Such inherited variants can involve numerical alterations, like aneuploidy, or structural changes, such as balanced translocations, and are often identified through parental karyotyping when a child presents with related phenotypes.[6] Transmission of inherited chromosome abnormalities follows mendelian patterns adapted to chromosomal scale. Structural abnormalities, such as balanced translocations, are typically passed in an autosomal dominant fashion, where phenotypically normal carrier parents have a 50% chance of transmitting the rearranged chromosome to each offspring, though only unbalanced forms may cause clinical issues.[1] Sex-linked abnormalities on the X or Y chromosomes exhibit X-linked inheritance, with males more severely affected due to hemizygosity, as seen in conditions involving X-chromosomal structural variants.[1] Mosaicism, where only a subset of germline cells carry the abnormality, introduces variable inheritance risks, potentially leading to gonadal mosaicism in parents and unpredictable transmission to multiple offspring.[1] Key mechanisms include meiotic segregation errors in carrier parents. For instance, parents with balanced reciprocal translocations face risks of producing unbalanced gametes through adjacent-1 or 3:1 segregation, resulting in partial trisomies or monosomies in offspring; viable unbalanced outcomes occur in approximately 10-15% of pregnancies for many translocations, though theoretical risks can reach 50% depending on chromosome involvement.[8] Aneuploidy inheritance is rarer due to meiotic selection against unbalanced gametes, which often fail to fertilize or implant, coupled with high rates of embryonic lethality for most autosomal aneuploidies, limiting multi-generational transmission primarily to viable cases like trisomy 21.[9] Risk factors for inherited chromosome abnormalities center on parental characteristics. Advanced maternal age over 35 years elevates the likelihood of nondisjunction during oogenesis, increasing the chance of transmitting aneuploid gametes, while paternal age has minimal impact.[6] A family history of chromosomal carriers, such as balanced translocation holders, substantially raises recurrence risks in subsequent generations, often prompting preconception screening.[10] Early recognition of inherited chromosome abnormalities occurred in the 1950s and 1960s through pedigree analysis, following the 1959 identification of trisomy 21 as a chromosomal cause of Down syndrome, which revealed familial clustering in some cases and established inheritance patterns for structural variants like translocations.[11][12] Inherited chromosomal abnormalities contribute to a small fraction (less than 5%) of congenital anomalies, with total chromosomal issues accounting for about 15%, though most overall chromosomal issues in newborns are de novo.[13][14]Acquired Abnormalities

Acquired chromosome abnormalities, also known as somatic abnormalities, refer to non-inherited genetic alterations that arise in body cells after fertilization, typically during an individual's lifetime, and are confined to specific tissues rather than being present in all cells. These changes occur in somatic cells and do not affect gametes, distinguishing them from germline mutations that can be passed to offspring. Unlike constitutional abnormalities present from birth, acquired ones often result from stochastic errors in DNA replication or external insults, leading to genomic instability that can drive clonal expansion in affected cell populations.[15] The mechanisms underlying acquired chromosome abnormalities include environmental exposures, viral infections, and intrinsic cellular processes such as aging-related replication errors. Ionizing radiation can induce DNA double-strand breaks, leading to chromosomal breaks, translocations, or aneuploidy in exposed cells, as observed in radiation-induced leukemias. Chemical agents like benzene, a known carcinogen, cause chromosome aberrations including aneuploidy and structural rearrangements in bone marrow cells, contributing to the development of acute myeloid leukemia. Viral infections, such as high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) in cervical cancer, promote chromosomal instability through integration into the host genome, disrupting DNA repair pathways and causing aneuploidy or amplifications. Additionally, aging contributes via cumulative replication errors during cell division, exacerbated by telomere shortening and oxidative stress, which generate reactive oxygen species that damage telomeric DNA and trigger chromosome end fusions or breakage-fusion-bridge cycles. Recent studies up to 2025 highlight how oxidative stress-induced telomere instability accelerates the acquisition of these abnormalities, fostering a pro-tumorigenic environment in aging tissues. As of 2025, CRISPR editing studies have elucidated how specific gene disruptions in DNA repair pathways accelerate acquired chromosomal instability in aging tissues.[16][17][18][19][20] These abnormalities play a central role in disease pathogenesis, particularly cancer, where they facilitate clonal evolution—the sequential accumulation of genetic changes that confer growth advantages to malignant cells. In chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), the Philadelphia chromosome arises as an acquired t(9;22) translocation in hematopoietic stem cells, creating the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene that drives leukemogenesis and subsequent clonal progression with additional aberrations. Prevalent types include numerical abnormalities like aneuploidy, such as trisomy 8 commonly seen in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes, which promotes tumor heterogeneity and progression. Structural changes, including gene amplifications like HER2 on chromosome 17q12 in breast cancer, enhance oncogene expression and are associated with aggressive tumor behavior. Somatic mutations, encompassing these chromosomal alterations, accumulate with age, and chromosomal instability is a feature in approximately 90% of cancers, underscoring its contribution to oncogenesis across tumor types.[21][22][23][24]Abnormalities Arising During Gametogenesis

Chromosome abnormalities arising during gametogenesis refer to de novo errors in chromosome segregation that occur specifically during meiosis I or II in the formation of sperm or eggs, resulting in aneuploid gametes with an abnormal number of chromosomes.[25] These errors primarily involve nondisjunction, where homologous chromosomes or sister chromatids fail to separate properly, leading to gametes that carry extra or missing chromosomes.[26] Such abnormalities are a leading cause of infertility and birth defects, as aneuploid gametes often produce nonviable embryos upon fertilization.[25] In spermatogenesis, chromosome abnormalities stem from vulnerabilities in meiotic processes, including DNA damage induced by oxidative stress and failures in the spindle assembly checkpoint that monitors chromosome alignment.[27] Oxidative stress arises from elevated reactive oxygen species levels in aging testes, which overwhelm antioxidant defenses and cause DNA strand breaks in germ cells.[27] Paternal age significantly exacerbates these risks; sperm aneuploidy rates in normal men typically range from 0.9% to 1.7%, with only slight or no significant increase in men over 40 years, remaining around 1-2% per chromosome analyzed.[25][28] In infertile men, these rates can be three times higher than in fertile individuals, often linked to structural issues like thickened basal membranes in seminiferous tubules that disrupt meiosis.[27] Oogenesis exhibits parallel mechanisms but with a pronounced maternal age effect, where nondisjunction risk escalates due to the prolonged arrest of oocytes in prophase I from fetal development until ovulation.[29] After age 35, the incidence of aneuploid oocytes rises sharply, from about 19% in women aged 23–40 to 65–78% in those over 40, primarily from errors in meiosis I.[25] This is attributed to progressive loss of cohesin proteins, such as SMC1, which stabilize chiasmata and prevent premature separation of chromosome arms during prolonged dictyate arrest.[29] For instance, the risk of any trisomic pregnancy (referring to any autosomal trisomy in clinically recognized pregnancies) increases from approximately 2% at age 25 to 35% at age 42, underscoring cohesin degradation as a key driver of age-related segregation failures.[29][30][31] Environmental factors, including toxins like pesticides and chemotherapy agents, further contribute to these abnormalities by inducing oxidative damage and disrupting meiotic progression in germ cells.[32] Pesticides such as DDT and deltamethrin generate free radicals that promote apoptosis and DNA fragmentation in spermatogonia and oocytes, elevating aneuploidy rates.[32] Chemotherapy drugs, including thalidomide derivatives, similarly trigger redox imbalances that impair spindle function and chromosome alignment during gametogenesis.[32] Exposure to perfluorinated compounds has been associated with increased chromosomal aneuploidies in spermatozoa, highlighting their interference with meiotic segregation.[32] The outcomes of aneuploid gametes are predominantly adverse, with most resulting in early embryonic arrest and miscarriage; chromosomal abnormalities account for 61% of first-trimester spontaneous abortions, including 37% autosomal trisomies and 9% polyploidies.[33] Viable pregnancies are rare but can lead to conditions like Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY), often arising from nondisjunction in maternal meiosis I, where an XX egg fertilizes with a Y sperm.[33] Such cases represent about 3.4% of chromosomally abnormal miscarriages but are 40 times more prevalent in abortuses than live births.[33] Recent research since 2020 has highlighted epigenetic modifications during gametogenesis as modulators of abnormality rates, with environmental exposures inducing heritable changes like DNA methylation and histone retention that persist across generations.[34] For example, ancestral exposure to pesticides like vinclozolin alters DNA methylation regions in prospermatogonia and spermatocytes, increasing transgenerational risks of meiotic errors and infertility.[34] Studies on histone H3 lysine-4 methylation have shown its role in regulating oocyte meiosis, where disruptions contribute to higher aneuploidy in aged or exposed germ cells.[34] These findings suggest that epigenetic reprogramming during meiosis I and II can either mitigate or amplify segregation defects, influencing overall gamete quality.[34]Detection and Diagnosis

Traditional Cytogenetic Methods

Cytogenetics is the branch of genetics that involves the direct microscopic analysis of chromosomes to study their number, size, shape, and structure, enabling the identification of abnormalities such as aneuploidy or large-scale rearrangements. This field relies on visual examination of stained chromosomes prepared from cell samples, providing a foundational approach for detecting chromosomal variations that may underlie genetic disorders. The development of traditional cytogenetic methods accelerated in the mid-20th century, with significant advancements in the late 1960s and 1970s through the introduction of chromosome banding techniques. Prior to banding, chromosomes were visualized using basic staining methods like those developed by Walther Flemming in the late 19th century, but these offered limited resolution for distinguishing individual chromosomes. Q-banding (quinacrine fluorescence), developed by Lore Zech and Torbjörn Caspersson in 1970, was the first differential banding technique. The breakthrough for routine use came with G-banding, independently discovered in 1971, notably by Marina Seabright, who used Giemsa staining after trypsin treatment to produce characteristic light and dark bands along chromosome arms, allowing for precise identification of each of the 46 human chromosomes and detection of structural anomalies.[35] Other banding methods, such as R-banding (reverse Giemsa), were introduced concurrently in 1971, further refining the ability to map chromosomal landmarks.[35] The standard procedure for karyotyping, the primary traditional cytogenetic technique, begins with obtaining a cell sample, typically from peripheral blood lymphocytes for postnatal analysis or amniotic fluid via amniocentesis for prenatal diagnosis. Cells are cultured in a nutrient medium to stimulate division, reaching the metaphase stage where chromosomes are most condensed and visible. To arrest cells in metaphase, colchicine or colcemid is added, which disrupts microtubule formation and halts spindle assembly, preventing chromosome segregation. Following this, a hypotonic solution (usually potassium chloride) is applied to swell the cells, improving chromosome spreading, after which they are fixed with a methanol-acetic acid mixture and dropped onto glass slides. The slides are then stained using G-banding protocols: chromosomes are briefly exposed to trypsin to partially digest proteins, followed by Giemsa dye, which binds preferentially to AT-rich regions, creating alternating G-positive (dark) and G-negative (light) bands. Under a light microscope at 400-550x magnification, a karyogram is constructed by arranging the banded chromosomes into pairs by size, centromere position, and banding pattern, with abnormalities scored against standard ideograms like those from the International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature (ISCN). This process achieves a resolution of approximately 5-10 megabases (Mb), sufficient for identifying large deletions, duplications, translocations, or numerical changes like trisomy 21 in Down syndrome. Traditional cytogenetic methods are widely applied in clinical settings for both prenatal and postnatal diagnosis. In prenatal testing, samples from chorionic villus sampling (CVS) at 10-13 weeks or amniocentesis at 15-20 weeks allow detection of fetal chromosomal issues, such as sex chromosome aneuploidies, with results guiding decisions on pregnancy management. Postnatally, blood samples from individuals with developmental delays or congenital anomalies are karyotyped to identify causes like Turner syndrome (45,X). These techniques excel at detecting whole-chromosome gains or losses and gross structural alterations that affect large genomic segments, providing a holistic view of the genome. Key advantages of traditional cytogenetics include the direct visualization of all chromosomes in a single analysis, offering an unbiased survey of the entire genome without requiring prior knowledge of specific loci, and its relative cost-effectiveness compared to advanced genomic sequencing. It remains a first-line tool in many laboratories due to its established protocols and interpretability by trained cytogeneticists. However, limitations are notable: the method's resolution restricts detection to abnormalities larger than 5-10 Mb, missing submicroscopic changes like small deletions in microdeletion syndromes; the process is labor-intensive, requiring 7-14 days for culture and analysis; and it demands viable, dividing cells, which can be challenging in certain tissues. Despite these constraints, traditional methods continue to play a crucial role in initial screening before escalating to higher-resolution techniques.Modern Molecular Techniques

Modern molecular cytogenetics has revolutionized the detection of chromosome abnormalities by providing sub-microscopic resolution, enabling the identification of genetic alterations too small to be visualized through traditional karyotyping.[36] These techniques focus on DNA-level analysis, bridging the gap between conventional cytogenetics and genomics to uncover copy number variations, structural rearrangements, and sequence-level changes with high precision.[36] A cornerstone technique is fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), which uses fluorescently labeled DNA probes to target specific chromosomal loci, such as telomeres or centromeres, allowing visualization of numerical and structural abnormalities in interphase or metaphase cells.[37] FISH is particularly valuable for rapid detection of aneuploidy or microdeletions in conditions like DiGeorge syndrome, offering targeted analysis without requiring cell culture.[37] Chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) represents a genome-wide approach to detect copy number variants (CNVs) and loss of heterozygosity, achieving resolutions as fine as 50 kb, far surpassing traditional methods for identifying submicroscopic imbalances associated with developmental disorders.[38] As a first-tier diagnostic tool, CMA scans the entire genome for deletions and duplications, providing comprehensive profiling in prenatal and postnatal settings.[38] Next-generation sequencing (NGS) enables whole-genome or targeted sequencing to detect aneuploidy, mosaicism, and complex rearrangements at the base-pair level, including through non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) that analyzes cell-free fetal DNA (cfDNA) in maternal blood.[39] NIPT via NGS achieves over 99% sensitivity and specificity for trisomies 13, 18, and 21, facilitating early screening with minimal risk.[40] In applications, these techniques support rapid prenatal screening, where NIPT has transformed risk assessment for common aneuploidies, and cancer genomics, where NGS profiles tumor-specific chromosomal alterations to guide personalized therapy.[39] For instance, NGS identifies somatic CNVs in leukemias, informing prognosis and treatment.[39] Recent advancements as of 2025 include the integration of single-cell sequencing, which reveals low-level mosaicism in embryonic tissues by analyzing individual cells for aneuploidy, enhancing detection in preimplantation genetic testing.[41] AI-assisted variant calling in NGS pipelines improves accuracy by automating the identification of chromosomal variants, reducing false positives in large-scale genomic data from cytogenetic studies.[42] These methods offer high sensitivity for microdeletions undetectable by conventional approaches and non-invasive options like NIPT, minimizing procedural risks.[38] However, they cannot visualize overall chromosome morphology or pairing during meiosis, and their higher costs limit accessibility in resource-constrained settings.[36]Nomenclature and Classification

Naming Conventions

The International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature (ISCN) provides a standardized framework for describing human chromosome complements and abnormalities, ensuring consistent communication across cytogenetic and genomic analyses. Originating from the Denver Conference in 1960, which proposed the initial system for numbering and classifying human mitotic chromosomes into seven groups (A-G) based on size and morphology, the nomenclature has evolved through subsequent international conferences in London (1963), Chicago (1966), and Paris (1971 and 1975) to incorporate banding techniques and structural details.[43] This progression culminated in the formal ISCN publications, with the first edition in 1978, and periodic updates reflecting advances in cytogenomics; the most recent edition, ISCN 2024, integrates nomenclature for emerging technologies like genome mapping while merging rules for numerical and structural findings into a unified chapter for clarity.[44][45] Numerical abnormalities are denoted by specifying the total chromosome count, followed by the sex chromosome constitution, and then the abnormality using a plus (+) or minus (-) sign with the chromosome number. For instance, trisomy 21 is represented as 47,XX,+21, indicating 47 chromosomes with an extra chromosome 21 in a female karyotype, while monosomy X (Turner syndrome) is 45,X, denoting 45 chromosomes with a single X. In cases of polyploidy or aneuploidy ranges, tildes (Examples of Common Abnormalities

Common chromosomal abnormalities are selected for illustration based on their relative frequency in clinical populations, allowing demonstration of the International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature (ISCN) for precise description.[49] These examples encompass numerical and structural variants across autosomes and sex chromosomes, as well as polyploidy, reflecting patterns observed in prenatal and postnatal cytogenetic analyses.[50] Autosomal numerical abnormalities include trisomy 21, the most prevalent aneuploidy, denoted as 47,XX,+21 in females or 47,XY,+21 in males, indicating an extra chromosome 21.[50] A common structural autosomal variant is the 22q11.2 deletion, represented as del(22)(q11.2), signifying loss of material at the q11.2 band on the long arm of chromosome 22; this notation highlights interstitial deletions detectable in routine karyotyping.[51] Sex chromosome aneuploidies frequently involve extra or missing X chromosomes. Klinefelter syndrome typically presents as 47,XXY, with an additional X chromosome in males, accounting for over 90% of cases.[52] Turner syndrome is denoted by 45,X, reflecting monosomy X due to absence of one sex chromosome.[53] Triple X syndrome, or 47,XXX, indicates an extra X in females and is a recognized numerical variant in population studies.[54] Structural rearrangements often appear balanced in carriers. A balanced reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 14 and 21 is notated as 46,XX,t(14;21) or 46,XY,t(14;21), preserving total genetic material but altering chromosome structure.[55] Robertsonian translocations, common fusions of acrocentric chromosomes, are exemplified by 45,XX,der(14;21)(q10;q10), where the derivative chromosome joins the long arms at centromeric regions q10, resulting in 45 chromosomes overall.[56] Polyploidy, though rarer and often lethal, includes triploidy denoted as 69,XXX (or 69,XXY), representing three full sets of chromosomes, frequently identified in early pregnancy losses.[57] In clinical cytogenetic laboratories, ISCN notation integrates seamlessly into reports to ensure unambiguous communication of findings, facilitating accurate genetic counseling and further testing.[58] For instance, a full karyotype description might combine sex chromosomes, total count, and abnormality symbols as in the examples above, adhering to ISCN guidelines for consistency across global labs.[49]Clinical Significance

Associated Conditions and Syndromes

Chromosome abnormalities often lead to syndromes by disrupting gene dosage, where an extra or missing copy of genetic material alters the expression levels of multiple genes, resulting in developmental and physiological imbalances.[2] This imbalance can cause a cascade of effects, including impaired cellular function, organ malformation, and increased susceptibility to certain diseases, as seen in various aneuploidies and structural variants.[1] For instance, trisomies typically result in overexpression of genes on the affected chromosome, contributing to characteristic phenotypic features across affected individuals.[59] Among autosomal trisomies, Down syndrome, caused by trisomy 21, is associated with intellectual disability, characteristic facial features such as upslanting palpebral fissures, and congenital heart defects like atrioventricular septal defects in approximately 40-50% of cases.[60] Edwards syndrome (trisomy 18) presents with severe developmental delays, intrauterine growth restriction, clenched fists, rocker-bottom feet, and life-threatening heart and kidney malformations, with most affected infants not surviving beyond the first year.[61] Similarly, Patau syndrome (trisomy 13) manifests with cleft lip and palate, polydactyly, microphthalmia, and profound intellectual disability, often accompanied by brain and heart anomalies that lead to high early mortality.[62] Structural abnormalities, such as deletions, also produce distinct syndromes through haploinsufficiency, where the loss of one gene copy impairs normal development. Cri-du-chat syndrome, resulting from a deletion on the short arm of chromosome 5 (5p-), features a high-pitched, cat-like cry in infancy, microcephaly, hypertelorism, and moderate to severe intellectual disability.[63] DiGeorge syndrome, due to a microdeletion at 22q11.2, is characterized by thymic hypoplasia leading to immune deficiency, conotruncal heart defects such as tetralogy of Fallot, hypocalcemia from parathyroid involvement, and palatal abnormalities.[64] Sex chromosome abnormalities similarly affect gene dosage, particularly of X-linked genes escaping inactivation. Turner syndrome (45,X) in females results in short stature, gonadal dysgenesis causing infertility and lack of secondary sexual characteristics, webbed neck, and increased risk of aortic coarctation and horseshoe kidney.[53] Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY) in males leads to hypogonadism with small testes and low testosterone, tall stature, gynecomastia, and learning difficulties, often with preserved fertility in milder cases but infertility common.[52] Mosaicism, where only some cells carry the abnormality, can lead to variable phenotypic severity depending on the proportion and distribution of affected cells. In mosaic Down syndrome, individuals may exhibit milder intellectual disability and fewer physical features compared to full trisomy 21, with outcomes influenced by the percentage of trisomic cells in critical tissues like the brain.[65] Epidemiologically, Down syndrome has an incidence of approximately 1 in 700 live births, with risk strongly correlated to advanced maternal age—for example, rising from about 1 in 1,500 at age 25 to 1 in 100 at age 40 due to increased meiotic nondisjunction.[66] Incidences for Edwards and Patau syndromes are lower, at roughly 1 in 5,000 and 1 in 5,000-10,000 live births, respectively, also linked to maternal age.[61][62] Recent research highlights how epigenetic modifiers, such as DNA methylation patterns altered by the extra chromosome, can influence the penetrance and expressivity of these syndromes, potentially modulating symptom severity beyond simple gene dosage effects in conditions like Down syndrome.[67]Management and Genetic Counseling

Management of chromosome abnormalities typically involves a multidisciplinary approach tailored to the specific type and severity of the abnormality, focusing on symptomatic treatment and supportive care to improve quality of life. For instance, in cases of Down syndrome (trisomy 21), which often includes congenital heart defects in approximately 40-50% of affected individuals, surgical interventions such as atrioventricular septal defect repair are commonly performed to address structural cardiac issues, with favorable outcomes and low mortality rates when managed early.[68] Early intervention therapies, including physical, occupational, and speech-language therapies, are recommended for infants and young children with chromosomal disorders like Down syndrome to enhance developmental milestones, with programs starting as early as birth under frameworks like those from the U.S. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.[69] These therapies can significantly mitigate delays in motor skills, communication, and cognition, often coordinated by teams comprising pediatricians, geneticists, cardiologists, and therapists.[70] Reproductive options for carriers of balanced chromosomal rearrangements or families with a history of abnormalities include preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), now termed preimplantation genetic testing for structural rearrangements (PGT-SR), which allows screening of embryos during in vitro fertilization (IVF) to select those without the abnormality before implantation.[71] This technique has been effective in reducing the transmission risk of conditions like reciprocal translocations, with success rates for healthy live births comparable to standard IVF when embryos are euploid.[72] Alternatives such as sperm or egg donation from unaffected donors provide another avenue for families at high risk, bypassing the need for carrier screening in gametes.[73] Genetic counseling plays a central role in supporting individuals and families affected by chromosome abnormalities, beginning with a comprehensive risk assessment that incorporates family pedigree analysis, personal medical history, and probabilistic modeling of recurrence risks based on the abnormality type—for example, a 10-15% empiric risk for unbalanced offspring in carriers of Robertsonian translocations.[74] Counselors facilitate informed consent for diagnostic testing by explaining options like karyotyping or chromosomal microarray, ensuring patients understand benefits, limitations, and potential psychological impacts.[75] Post-diagnosis, counseling extends to emotional support, resource referral, and long-term planning, helping families navigate decisions about family building or care management.[76] As of 2025, advancements in gene editing technologies offer emerging potential for addressing certain genetic disorders linked to chromosomal abnormalities, though clinical applications remain limited to monogenic conditions analogous to structural variants. Experimental approaches, such as CRISPR-mediated chromosome elimination, show promise in preclinical models for correcting aneuploidy by targeting supernumerary chromosomes, but human trials for monosomies like Turner syndrome (45,X) are still in early research phases focused on gene therapy to supplement missing gene products rather than full chromosomal restoration.[77] These developments highlight the technology's potential but underscore challenges like off-target effects and delivery efficiency in somatic cells.[78] Ethical considerations in management and counseling for chromosome abnormalities include the implications of selective termination following prenatal diagnosis, where nondirective counseling aims to respect autonomy while addressing potential coercion or stigmatization of disabilities.[79] Uncertainties in mosaicism, where only a subset of cells carry the abnormality, complicate prognostic counseling and decision-making, as variability in phenotypic expression can lead to incomplete risk information and ethical dilemmas around testing accuracy.[80] Counselors must navigate confidentiality, especially in familial implications, and promote equitable access to options without exacerbating social disparities.[81] Support resources for affected families include organizations like the Rare Chromosome Disorder Support Group (Unique), which provides international networking, educational materials, and advocacy for over 100 rare chromosomal conditions.[82] Chromosome Disorder Outreach, Inc., offers peer support, newsletters, and family connections for those with deletions, duplications, or other structural variants.[83] Specialized registries, such as those under the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), facilitate research participation and connect families to clinical trials, while groups like Support Organization for Trisomy (SOFT) focus on trisomy 13, 18, and related disorders with annual conferences and care guides.[84][85]References

- Feb 24, 2021 · The Ph chromosome is present in 95% of the CML patients and variant Ph chromosome translocations can involve three or more chromosomes[45].

- Family history: Having a family history of a chromosomal abnormality increases the risk. If a couple has had one baby with the most common form of Down syndrome ...

![Three chromosomal abnormalities with ISCN nomenclature, with increasing complexity: (A) A tumour karyotype in a male with loss of the Y chromosome, (B) Prader–Willi Syndrome i.e. deletion in the 15q11-q12 region and (C) an arbitrary karyotype that involves a variety of autosomal and allosomal abnormalities.[55]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6b/Three_chromosomal_abnormalities_with_ISCN_nomenclature.png/900px-Three_chromosomal_abnormalities_with_ISCN_nomenclature.png)