Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

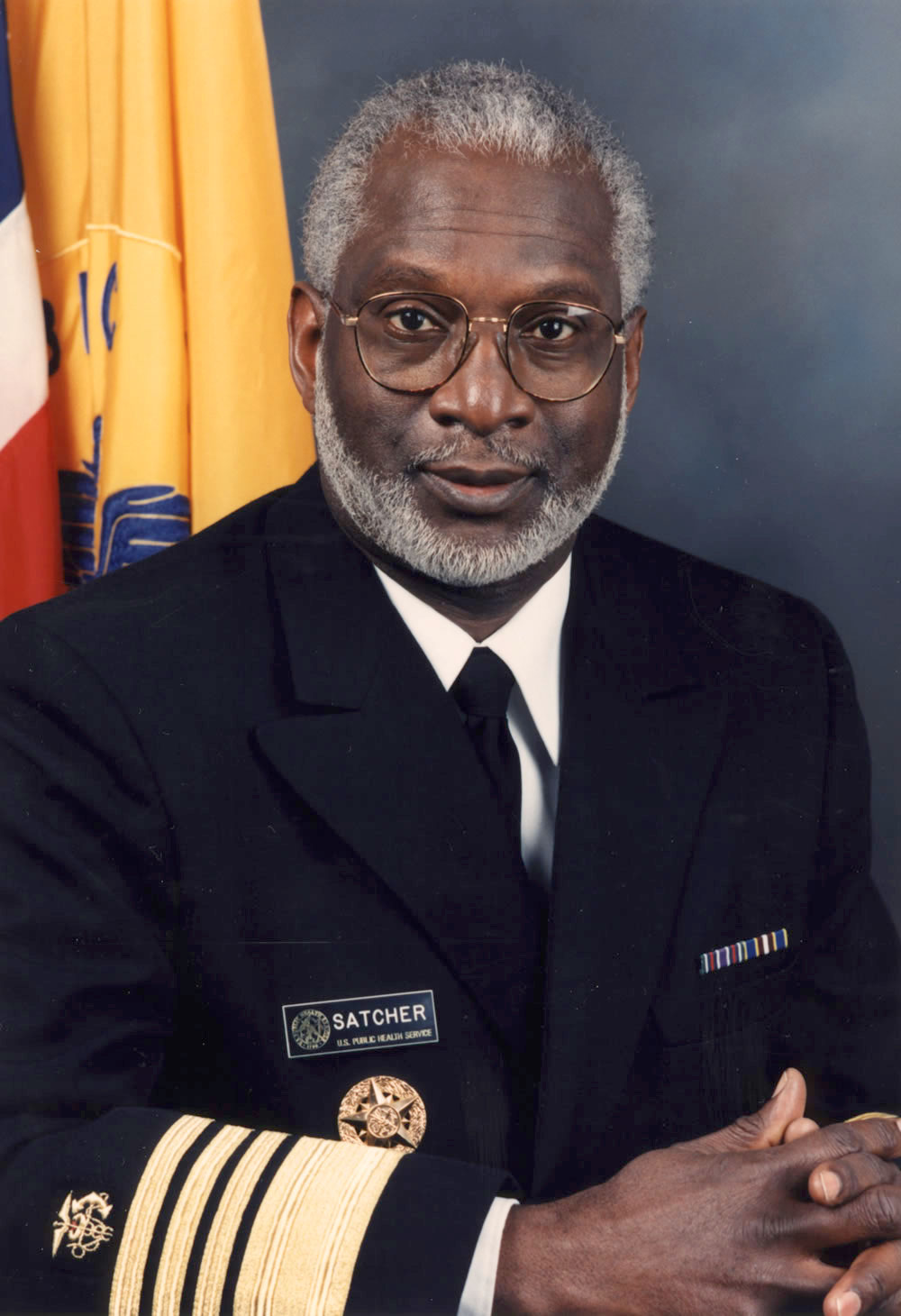

David Satcher

View on Wikipedia

David Satcher (born March 2, 1941) is an American physician, and public health administrator. He was a four-star admiral in the United States Public Health Service Commissioned Corps and served as the 11th Assistant Secretary for Health, and the 16th Surgeon General of the United States.

Key Information

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]Satcher was born in Anniston, Alabama. At the age of two, he contracted whooping cough. A Black doctor, Dr. Jackson, came to his parents' farm, and told his parents he didn't expect David to live, but nonetheless spent the day with him and told his parents how to give him the best chance he could.[1] Satcher said that he grew up hearing that story, and that inspired him to be a doctor.[2] While in college, Satcher was active in the Civil Rights Movement and was arrested on multiple occasions.[3]

Satcher graduated from Morehouse College in Atlanta in 1963 and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. He received his MD and a PhD in cell biology from Case Western Reserve University in 1970 with election to the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society.[4] He completed his residency and fellowship training at the Strong Memorial Hospital, University of Rochester, the UCLA School of Medicine, and Martin Luther King Jr.-Harbor Hospital. He is a fellow of the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Preventive Medicine, and the American College of Physicians, and is board certified in preventive medicine.[4] Satcher pledged Omega Psi Phi fraternity and is an initiate of the Psi chapter of Morehouse College.[5]

Career

[edit]From December 1977 to August 1979, Satcher served as the Acting Dean of the Charles R. Drew Postgraduate Medical School (now the Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, also known as "Drew"). He had previously served as the Chairman of the Drew's Department of Family Medicine.[6] In May 1978, during his deanship term, a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) was approved by the University of California Board of Regents to adopt a joint medical education program between the UCLA School of Medicine and Drew; the Drew/UCLA M.D. program welcomed its first class of students in 1981.[6]

Satcher served as professor and Chairman of the Department of Community Medicine and Family Practice at Morehouse School of Medicine from 1979 to 1982. He is a former faculty member of the UCLA School of Medicine, the UCLA School of Public Health, and the King-Drew Medical Center in Los Angeles (known as the Martin Luther King Jr. Outpatient Center at the time of its closure in 2007), where he developed and chaired the King-Drew Department of Family Medicine.[7] He also directed the King-Drew Sickle Cell Research Center for six years. Satcher served as President of Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, from 1982 to 1993.[4] He held the posts of Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Administrator of the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry from 1993 to 1998. Satcher was the first Black American to hold the CDC Director position.[8]

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome scandal

[edit]Under Satcher's leadership, the CDC took millions of dollars Congress set aside for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) research and secretly spent the funds in other areas.[9] The misappropriation of funds continued for three years (from 1995–1998) and the CDC attempted to cover up their actions. The issue only came to light after a CDC employee filed a whistleblower report and a special Inspector General was appointed to investigate the matter.[10] In the words of Martha Katz, Deputy Director for Policy and Legislation at CDC: "Resources intended for CFS were actually used for measles, polio and other disease areas. This was a breach of CDC's solemn trust and is in direct conflict with its core values."[9]

Surgeon General

[edit]

Satcher served simultaneously in the positions of Surgeon General and Assistant Secretary for Health from February 1998 through January 2001 at the US Department of Health and Human Services.[11] As such, he is the first Surgeon General to be appointed as a four-star admiral in the PHSCC, a departure from the Surgeon General's normal appointment to three-star vice general, to reflect his dual offices.[12]

In his first year as Surgeon General, Satcher released the 1998 Surgeon General's report "Tobacco Use Among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups." In it, he reported that tobacco use was on the rise among youth in each of the country's major racial and ethnic groups, threatening their long-term health prospects.[13]

Satcher was appointed by Bill Clinton, and remained Surgeon General until 2002, contemporaneously with the first half of the first term of George W. Bush's presidential administration. Eve Slater would later replace him as Assistant Secretary for Health in 2001. Because he no longer held his dual office, Satcher was reverted and downgraded to the grade of vice admiral in the regular corps for the remainder of his term as Surgeon General. In 2001, his office released the report, The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Promote Sexual Health and Responsible Sexual Behavior. The report was hailed by the chairman of the American Academy of Family Physicians as an overdue paradigm shift—"The only way we're going to change approaches to sexual behavior and sexual activity is through school. In school, not only at the doctor's office."[14] However, conservative political groups denounced the report as being too permissive towards homosexuality and condom distribution in schools. When Satcher left office, he retired with the rank of vice admiral.

Post–Surgeon General

[edit]Upon his departure from the post, Satcher became a fellow at the Kaiser Family Foundation. In the fall of 2002, he assumed the post of Director of the National Center for Primary Care at the Morehouse School of Medicine.

On December 20, 2004, Satcher was named interim president at Morehouse School of Medicine until John E. Maupin, Jr., former president of Meharry Medical College assumed the current position on February 26, 2006.[citation needed] In June 2006, Satcher established the Satcher Health Leadership Institute (SHLI) at Morehouse School of Medicine as a natural extension of his experiences improving public health policy for all Americans and his commitment to eliminating health disparities for minorities, the poor, and other disadvantaged groups.[15]

In 2013, he co-founded the advocacy group African American Network Against Alzheimer's.[16]

Satcher sat on the boards of directors of Johnson & Johnson from 2002 to 2012, and MetLife from 2007 to 2012.[17][18][19][20]

Criticisms of health inequality

[edit]While acknowledging progress, Satcher has criticized health disparities. In a 2005 article published in the journal Health Affairs, Satcher and his oc-authors asked the question, "What if we had eliminated disparities in health in the last century?" and estimated, based on 2002 data, that "83,570 excess deaths could be prevented each year in the United States if [the] black-white mortality gap could be eliminated."[21]

In a 2006 essay for PLOS Medicine discussing the Health Affairs article, Satcher stated that the study's estimates included 24,000 fewer Black deaths from cardiovascular disease and, if infant mortality had been equal across racial and ethnic groups in 2000, 4,700 fewer Black infants would have died in their first year of life.[22] Without disparities, there would have been 22,000 fewer Black deaths from diabetes and almost 2,000 fewer Black women would have died from breast cancer; 250,000 fewer Black patients would have been infected with HIV/AIDS and 7,000 fewer Black patients would have died from complications due to AIDS in 2000. As many as 2.5 million additional Black individuals, including 650,000 children, would have had health insurance in that year. He called on people to work for solutions at the individual, community, and policy level.[22]

Satcher supports a Medicare-for-all style single payer health plan, in which insurance companies would be eliminated and the government would pay health care costs directly to doctors, hospitals and other providers through the tax system.[23]

In 1990, while President of Meharry Medical College, Satcher founded a quarterly academic journal entitled the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved.

Awards and honors

[edit]Satcher is the recipient of many honorary degrees and numerous distinguished honors, including:

- the Public Health Service Distinguished Service Medal

- an honorary Doctor of Public Health from Dickinson College (2016)[24]

- the UC Berkeley School of Public Health Public Health Heroes Award (2013)[25]

- an honorary Doctor of Science from Harvard University (2011)[26]

- the Bennie Mays Trailblazer Award (1999)[27]

- the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Award for Humanitarian Contributions to the Health of Humankind from the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases (1999)[28]

- the New York Academy of Medicine Lifetime Achievement Award (1997)[27]

- the Breslow Award in Public Health (1995)[29]

He has also won top awards from the American Medical Association, the American College of Physicians, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and Ebony magazine.[30] An academic society at the Case Western Reserve School of Medicine is named in Satcher's honor, and, in 2009, he delivered the university's Commencement Address.[31][32] The Case Western Reserve School of Medicine also created the David Satcher Clerkship for Underrepresented Minority Students in 1991. The clerkships hosts four to eight minority fourth-year medical students from outside of northeast Ohio at University Hospitals, where they receive exposure to career opportunities in an academic medical center as a part of the residency recruitment process.[33]

References

[edit]- ^ Stolberg, Sheryl Gay (September 13, 1997). "Man in the News; 'America's Doctor' David Satcher". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 13, 2025.

- ^ Dr. David Satcher (March 12, 2002). "The Tavis Smiley Show" (Interview). Interviewed by Tavis Smiley.

- ^ Marlene Cimons (July 3, 2020). "How Fauci, 5 other health specialists deal with covid-19 risks in their everyday lives". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

Satcher: I was quite active in the civil rights movement when I was a student at Morehouse. I went to jail at least five times. What bothers me about today's protests is that they aren't as organized as we were.

- ^ a b c "David Satcher". www.k-state.edu. Retrieved February 12, 2025.

- ^ "About Omega – Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc". Retrieved February 13, 2025.

- ^ a b "History | Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science". September 14, 2023. Archived from the original on January 14, 2025. Retrieved February 12, 2025.

- ^ Davis, David (May 7, 2000). "David Satcher". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 12, 2025.

- ^ "David Satcher, MD, PhD (First African-American Named to Head the CDC, and First African-American Man Named Surgeon General, HHS) | Perspectives Of Change". perspectivesofchange.hms.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on December 5, 2024. Retrieved February 12, 2025.

- ^ a b Mara Sheldon (July 30, 1999). "Misuse of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Research Monies by CDC Admitted". The Chronic Fatigue and Immune Dysfunction Syndrome Association of America (Press release) – via US Newswire.

- ^ Joe Stephens; Valerie Strauss (August 6, 1999). "Retaliation Alleged At CDC". The Washington Post.

- ^ "David Satcher | American Physician & Public Health Advocate". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "The Honorable Dr. David Satcher's Biography". The HistoryMakers. Retrieved February 12, 2025.

- ^ "Surgeon General's Report Warns of Health Reversals as Minority Teen Smoking Increases" (Press release). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. April 27, 1998. Archived from the original on September 23, 2008.

- ^ Schemo, Diana Jean (June 29, 2001). "Surgeon General's Report Calls for Sex Education Beyond Abstinence". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 13, 2025.

- ^ "Satcher Health Leadership Institute".

- ^ "AfricanAmericansAgainstAlzheimer's". UsAgainstAlzheimer's.

- ^ "Former U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher Elected to Johnson & Johnson Board" (Press release). Johnson & Johnson. April 17, 2002. Archived from the original on June 2, 2023.

- ^ "Johnson & Johnson Annual Report," Johnson & Johnston. 2012. https://www.annualreports.co.uk/HostedData/AnnualReportArchive/j/NYSE_JNJ_2012.pdf

- ^ "Former surgeon general joins MetLife board". Global Reinsurance. January 16, 2007.

- ^ "MetLife Annual Report," Metlife, Inc. 2012. https://www.annualreports.com/HostedData/AnnualReportArchive/m/NYSE_MET_2012.pdf

- ^ Satcher, David; Fryer, George E.; McCann, Jessica; Troutman, Adewale; Woolf, Steven H.; Rust, George (March 2005). "What If We Were Equal? A Comparison Of The Black-White Mortality Gap In 1960 And 2000". Health Affairs. 24 (2): 459–464. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.459. ISSN 0278-2715. PMID 15757931.

- ^ a b Satcher, David (October 24, 2006). "Ethnic Disparities in Health: The Public's Role in Working for Equality". PLOS Med. 3 (10): e405. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030405. PMC 1621093. PMID 17076554.

- ^ "Physicians Propose Solution to Rising Health Care Costs and Uninsured" (Press release). Physicians for a National Health Program. February 3, 2003.

- ^ Foreman, Michael. "2016 Commencement Citations". dickinson.edu. Retrieved February 13, 2025.

- ^ "UC Berkeley School of Public Health announces 2013 'public health heroes'". Berkeley Health Online. December 6, 2012. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ "Harvard awards 9 honorary degrees". Harvard Gazette. May 26, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2025.

- ^ a b "OJJDP National Conference Program," U.S. Department of Justice Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. 2000.https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/186310NCJRS.pdf

- ^ "David Satcher, MD, PhD – NFID". nfid.org. Retrieved February 13, 2025.

- ^ "U.S. Surgeon General to address Pitt graduates". utimes.pitt.edu. March 22, 2001. Retrieved February 13, 2025.

- ^ "David Satcher, MD, PhD – Kennedy Satcher". Retrieved February 13, 2025.

- ^ "Satcher Society | School of Medicine | School of Medicine | Case Western Reserve University". case.edu. February 28, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2025.

- ^ Case Western Reserve University (May 28, 2009). 2009 Commencement Convocation Keynote Speech - David Satcher. Retrieved February 13, 2025 – via YouTube.

- ^ "David Satcher Clerkship for Underrepresented Minority Students | School of Medicine | School of Medicine | Case Western Reserve University". case.edu. January 2, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2025.

External links

[edit]- Morehouse School of Medicine Faculty Profile

- Office of Public Health and Science (January 4, 2007). "David Satcher (1998–2002)". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on December 5, 2007. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- Satcher Interview on Healthcare as a Civil Rights Issue with Al Sharpton and Dr. V on AskDoctorv.com

- "MedicalMakers: David Satcher". The HistoryMakers website. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- Appearances on C-SPAN