Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Deep operation

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| War (outline) |

|---|

|

Deep operation (Russian: Глубокая операция, glubokaya operatsiya), also known as Soviet deep battle, was a military theory developed by the Soviet Union for its armed forces during the 1920s and 1930s. It was a tenet that emphasized destroying, suppressing or disorganizing enemy forces not only at the line of contact but also throughout the depth of the battlefield.

The term comes from Vladimir Triandafillov, an influential military writer, who worked with others to create a military strategy with specialized operational art and tactics. The concept of deep operations was a state strategy, tailored to the economic, cultural and geopolitical position of the Soviet Union. In the aftermath of the failures in the Russo-Japanese War, the First World War, and the Polish–Soviet War the Soviet High Command (Stavka) focused on developing new methods for the conduct of war. This new approach considered military strategy and tactics and introduced a new intermediate level of military art: operations. The Soviet Union's military was the first to officially distinguish the third level of military thinking which occupied the position between strategy and tactics.[1]

The Soviets developed the concept of deep battle and by 1936 it had become part of the Red Army field regulations. Deep operations had two phases: the tactical deep battle, followed by the exploitation of tactical success, known as the conduct of deep battle operations. Deep battle envisaged the breaking of the enemy's forward defenses, or tactical zones, through combined arms assaults, which would be followed up by fresh uncommitted mobile operational reserves sent to exploit the strategic depth of an enemy front. The goal of a deep operation was to inflict a decisive strategic defeat on the enemy's logistical structure and render the defence of their front more difficult, impossible, or irrelevant. Unlike most other doctrines, deep battle stressed combined arms cooperation at all levels: strategic, operational, and tactical.

History

[edit]Before deep battle

[edit]The Russian Empire had kept pace with its enemies and allies and performed well in its wars up to the 19th century. Despite some notable victories in the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) and in various Russo-Turkish Wars, defeats in the Crimean War (1853–1856), Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), the First World War (1914–1918) and the Polish–Soviet War (1918–1921) highlighted the weaknesses in Russian and Soviet military training, organization and methods.[2][need quotation to verify]

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, the new Bolshevik regime sought to establish a new military system that reflected the Bolshevik revolutionary spirit. The new Red Army (founded in 1918) combined the old and new methods. It still relied on the country's enormous manpower reserves and the Soviet program to develop heavy industry, which began in 1929, also raised the technical standards of Soviet arms industries to the level of other European nations. Once that had been achieved,[when?] the Soviets turned their attention to solving the problem of military operational mobility.[3][need quotation to verify]

Advocates of the development included Alexander Svechin (1878–1938), Mikhail Frunze (1885–1925) and Mikhail Tukhachevsky (1893–1937). They promoted the development of military scientific societies and identified groups of talented officers. Many of these officers entered the Soviet Military Academy during Tukhachevsky's tenure as its commandant in 1921–1922. Others came later, particularly Nikolai Varfolomeev (1890–1939) and Vladimir Triandafillov (1894–1931), who made significant contributions to the use of technology in deep offensive operations.[4]

Roots of deep battle

[edit]In the aftermath of the wars with Japan as well as experiences gained during the Russian Civil War several senior Soviet commanders called for a unified military doctrine. The most prominent was Frunze.[5] The call prompted opposition by Leon Trotsky.[6] Frunze's position eventually found favour with the officer elements that had experienced the poor command and control of Soviet forces in the conflict with Poland during the Polish–Soviet War. That turn of events prompted Trotsky's replacement by Frunze in January 1925.

The nature of this new doctrine was to be political. The Soviets were to fuse the military with the Bolshevik ideal, which would define the nature of war for the Soviet Union. The Soviets believed their most likely enemy would be the capitalist states of the west they had defended themselves against before and that such a conflict was unavoidable. The nature of the war raised four questions,

- Would the next war be won in one decisive campaign or would it be a long struggle of attrition?

- Should the Red Army be primarily offensive or defensive?

- Would the nature of battle be fluid or static?

- Would mechanized or infantry forces be more important?[7]

The discussion evolved into debate between those, like Svechin, who advocated a strategy of attrition, and others, like Tukhachevsky, who thought that a strategy of decisive destruction of the enemy forces was needed. The latter opinion was motivated in part by the condition of the Soviet Union's economy: the country was still not industrialized and thus was economically too weak to fight a long war of attrition.[8] By 1928 Tukhachevsky's ideas had changed: he considered that given the nature and lessons of World War I, the next big war would almost certainly be one of attrition. He thought that the vast size of the Soviet Union ensured that some mobility was still possible. Svechin accepted that and allowed for the first offensives to be fast and fluid but ultimately he decided that it would come down to a war of position and attrition. That would require a strong economy and a loyal and politically-motivated population to outlast the enemy.[7]

The doctrine pursued by the Soviets was offensively orientated. Tukhachevsky's neglect of defense pushed the Red Army toward the decisive battle and cult of the offensive mentality, which along with other events, caused enormous problems in 1941.[9] Unlike Tukhachevsky, Svechin thought that the next war could be won only by attrition, not by decisive battle. Svechin also argued that a theory of alternating defensive and offensive action was needed. Within that framework, Svechin also recognised the theoretical distinction of operational art that lay between tactics and strategy. In his opinion the role of the operation was to group and direct tactical battles toward a series of simultaneous operational objectives along a wide front, either directly or indirectly, to achieve Stavka's strategic target(s).[9] This became the blueprint for Soviet deep battle.

In 1929, Triandafillov and Tukhachevsky formed a partnership to create a coherent system of principles from the concept formed by Svechin. Tukhachevsky was to elaborate the principles of the tactical and operational phases of deep battle.[10] In response to his efforts and in acceptance of the methodology, the Red Army produced the Provisional Instructions for Organizing the Deep Battle manual in 1933. This was the first time that "deep battle" was mentioned in official Red Army literature.[11]

Principles

[edit]Doctrine

[edit]Deep battle encompassed manoeuvre by multiple Soviet Army front-size formations simultaneously. It was not meant to deliver a victory in a single operation; instead, multiple operations, which might be conducted in parallel or successively, would induce a catastrophic failure in the enemy's defensive system.

Each operation served to divert enemy attention and keep the defender guessing about where the main effort and the main objective lay. In doing so, it prevented the enemy from dispatching powerful mobile reserves to the area. The army could then overrun vast regions before the defender could recover. The diversion operations also frustrated an opponent trying to conduct an elastic defence. The supporting operations had significant strategic objectives themselves and supporting units were to continue their offensive actions until they were unable to progress any further. However, they were still subordinated to the main/decisive strategic objective determined by the Stavka.[12]

Each of the operations along the front would have secondary strategic goals, and one of those operations would usually be aimed towards the primary objective.

The strategic objective, or mission, was to secure the primary strategic target. The primary target usually consisted of a geographical objective and the destruction of a proportion of the enemy armed forces. Usually the strategic missions of each operation were carried out by a Soviet front. The front itself usually had several shock armies attached to it, which were to converge on the target and encircle or assault it. The means of securing it was the job of the division and its tactical components, which Soviet deep battle termed the tactical mission.

Terminology, force allocation and mission

[edit]| Mission | Territory | Actions | Force allocation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategic aim | Theatre of operations | Strategic operation | Strategic unit (front) |

| Strategic mission | Strategic direction | Front operation | Operational-strategic unit (front) |

| Operational mission | Operational direction | Army-size operation battle | Operational unit (shock army/corps) |

| Tactical mission | Battlefield | Battle | Operational-tactical unit (shock army/corps/army division) |

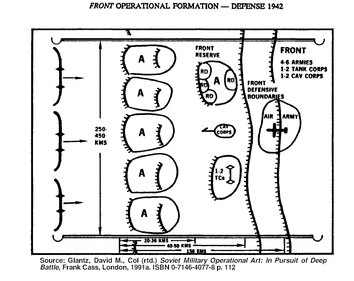

The concept of deep battle was not just offensive. The theory took into account all forms of warfare and decided both the offensive and defensive should be studied and incorporated into deep battle. The defensive phase of deep battle involved identifying crucial strategic targets and securing them against attack from all directions. As with the offensive methods of deep battle, the target area would be identified and dissected into operational and tactical zones. In defence, the tactical zones, forward of the objective would be fortified with artillery and infantry forces. The outer and forwardmost defences would be heavily mined, making a very strong static defence position. The tactical zones would have several defence lines, one after the other, usually 12 kilometres from the main objective. In the zone 1–3 km from the main objective, shock forces, which contained the bulk of the Soviet combat formations, would be positioned.[14]

The goal of the defence in depth concept was to blunt the elite enemy forces, which would be first to breach the Soviet lines, several times, causing them to exhaust themselves. Once the enemy had become bogged down in Soviet defences, the operational reserves came into play. Being positioned behind the tactical zones, the fresh mobile forces consisting of mechanized infantry, foot infantry, armored forces, and powerful tactical air support would engage the worn down enemy in a counter-offensive and either destroy it by attacking its flank or drive it out of the Soviet tactical zone and into enemyheld territory as far as possible.[14]

Tukhachevsky's legacy

[edit]There are three standard doctrines about the military that help understand deep battle, as adopted by the US Army and the US Marine Corps:

1. Tactic

The lowest level is tactical, an aspect of individual skill and organization size.

2. Strategy

The highest level, an aspect of theater operation and the leadership of organization and of a government.

3. Operational

Operational is the bridge between tactics and strategy.

According to Colonel McPadden (US Army), the most precious legacy of Tukhachevsky is his concepts about all operations theory including the "operational art". Tukhachevsky is the first who used 'operational' as a systematic concept. According to McPadden, the main skill of a military commander is dependent on Tukhachevsky's theory, which is the ability to integrate tactics and strategy. This involves the capability of a commander on "the use of military forces to achieve strategic goals through the design, organization, integration and conduct of theater strategies, campaigns, major operations and battles."[15]

Isserson; the factor of depth

[edit]Georgii Samoilovich Isserson (1898–1976) was a prolific writer on military tactics and operations. Among his most important works on operational art were The Evolution of Operational Art (1932 and 1937) and Fundamentals of the Deep Operation (1933). The latter work remains classified to this day.[16]

Isserson concentrated on depth and the role it played in operations and strategy. According to his view, strategy had moved on from Napoleonic times and the strategy of a single point (the decisive battle) and the Moltke era of linear strategy. The continuous front that developed in the First World War would not allow the flanking moves of the pre-1914 period. Isserson argued that the front had become devoid of open flanks and military art faced a challenge to develop new methods to break through a deeply echeloned defence. To this end he wrote that "we are at the dawn of a new epoch in military art, and must move from a linear strategy to a deep strategy."[16]

Isserson calculated that the Red Army's attack echelon must be 100 to 120 km deep. He estimated that enemy tactical defences, in about two lines, would be shallow in the first and stretch back 56 km. The second line would be formed behind and have 12–15 km of depth. Beyond that lay the operational depth, which would be larger and more densely-occupied than the first by embracing the railheads and supply stations to a depth of 50–60 km. There, the main enemy forces were concentrated. The third zone, beyond the operational depth was known as the strategic depth and served as the vital link between the country's manpower reservoirs and industrial power-supply sites and the area of military operations. In this zone lay the headquarters of the strategic forces, which included the army group level.[16]

Isserson much like Varfolomeev divided his shock armies, one for the task of breaking the enemy forward (or frontline defences) and the other to exploit the breakthrough and occupy the operational zone, while destroying enemy reserve concentrations as they attempted to counter the assault. The exploitation phase would be carried out by combined arms teams of mechanized airborne infantry and motorised forces.[17]

The breadth of the attack zone was an important factor in Soviet calculations. Isserson asserted an attack over a frontage of 70–80 km would be best. Three or four rifle corps would make a breakthrough along a front of 30 km. The breakthrough zone (only under favourable conditions) might be expanded to 48–50 km with another rifle corps. Under these conditions, a rifle corps would attack along a 10–12 km front, with each division in the corps' first echelon allocated a 6 kilometre frontage. A fifth supporting rifle corps would make diversionary attacks along the flanks of the main thrust to tie down counterresponses, confuse the enemy as to the area of the main thrust and delay its reserves from arriving.[17]

Tactical deep battle

[edit]Once the strategic objectives had been determined and operational preparation completed the Red Army would be tasked with assaulting the tactical zones of the enemy front in order to break through into its rear, allowing operationally mobile forces to invade the undefended enemy-held area to the rear. The Soviet rifle corps was essential to the tactical method. As the largest tactical unit it formed the central component of the tactical deep battle. The rifle corps usually formed part of a larger operational effort and would be reinforced with tanks, artillery and other weapons. Several corps would take part in the attack, some with defensive missions and others with offensive assignments. They were known as holding and shock groups, respectively.[18]

The order of battle was to encompass three echelons. The first echelon, acting as the first layer of forces, would come into immediate contact with opposing forces to break the tactical zones. The follow on echelons would support the breakthrough and the reserve would exploit it operationally. The holding group would be positioned on either flank of the combat zone to tie down enemy reinforcements via means of diversion attacks or blocking defence.

Nevertheless, despite the diversion being a primary mission, the limited forces conducting holding actions would be assigned geographical objectives. Once the main thrust had defeated the enemy's main defence, the tactical holding forces were to merge with the main body of forces conducting the operations.[19]

In defence, the same principles would apply. The holding group would be positioned forward of the main defensive lines. The job of the holding echelons in that event was to weaken or halt the main enemy forces. If that was achieved, the enemy would be weakened sufficiently to be caught and impaled on the main defence lines. If that failed, and the enemy succeeded in sweeping aside the holding forces and breaching several of the main defence lines, mobile operational reserves, including tanks and assault aviation, would be committed. These forces would be allocated to holding and shock groups alike and were often positioned behind the main defences to engage the battle worn enemy thrust.[19]

The forces used to carry out the tactical assignments varied from 1933 to 1943. The number of shock armies, rifle corps, and divisions (mechanized and infantry) given to a strategic front constantly changed. By 1943, the year that the Red Army began to practice deep battle properly, the order of battle for each tactical unit under the command of a front were:

Rifle army

- 3 rifle corps

- 7–12 rifle divisions

- 4 artillery regiments

- One field artillery regiment

- One anti-tank gun regiment

- anti-aircraft artillery regiment

- One mortar regiment

- One signal regiment

- One communication battalion

- One telegraph company

- One aviation communication troop

Stavka operational forces

- 1–2 artillery divisions

- 3 artillery regiments

- 3 tank destroyer regiments

- 3–4 tank or self-propelled gun brigades

- 10 separate tank or self-propelled gun regiments

- 2 anti-aircraft divisions

- 1–2 mechanized corps

These forces numbered some 80,000–130,000 men, 1,500–2,000 guns and mortars, 48-497 rocket launchers, and 30-226 self-propelled guns.[20]

Rifle corps

- 3 Rifle divisions

- One artillery regiment

- One signals battalion

- One sapper battalion

Rifle division

- 3 Rifle regiments

- One artillery regiment

- One anti-tank battalion

- One sapper battalion

- One signal company

- One reconnaissance company

The division numbered some 9,380 men (10,670 in a guards rifle division), 44 field guns, 160 mortars and 48 anti-tank guns.[20]

Deep operation

[edit]Soviet analysts recognised that it was not enough to break through the enemy tactical zone. Although that was the crucial first step, tactical deep battle offered no solution about how a force could sustain an advance beyond it and into the operational and strategic depths of an enemy front. The success of tactical action counted for little in an operational defensive zone that extended dozens of kilometres and in which the enemy held large reserves. Such enemy concentrations could prevent the exploitation of a tactical breakthrough and threaten the operational advance.[21]

That was demonstrated during the First World War, when initial breakthroughs were rendered useless by the exhaustion during the tactical effort, limited mobility, and a slow-paced advance and enemy reinforcements. The attacker was further unable to influence the fighting beyond the immediate battlefield because of the limited range, speed and reliability in the existing weapons. The attacker was often unable to exploit tactical success in even the most favourable circumstances, as his infantry could not push into the breach rapidly enough. Enemy reinforcements could then seal off the break in their lines.[21]

By the early 1930s, however, new weapons had come into circulation. Improvements in the speed and range of offensive weaponry matched those of its defensive counterparts. New tanks, aircraft and motorised vehicles were entering service in large numbers to form divisions and corps of air fleets, motorised and mechanized divisions. Those trends prompted the Red Army strategists to attempt to solve the problem of maintaining operational tempo with new technology.[21]

The concept was termed "deep operations" (glubokaya operatsiya), which emerged in 1936 and was placed within the context of deep battle in the 1936 Field Regulations. The deep operation was geared toward operations at the Army and or Front level and was larger, in terms of the forces engaged, than deep battle's tactical component, which used units not larger than corps size.[21]

The forces used in the operational phase were much larger. The Red Army proposed to use the efforts of air forces, airborne forces and ground forces to launch a "simultaneous blow throughout the entire depth of the enemy's operational defense" to delay its strongest forces positioned in the area of operations by defeating them in detail; to surround and destroy those units at the front (the tactical zone, by occupying the operational depth to its rear); and to continue the offensive into the defender's operational and strategic depth.[22]

The central composition of the deep operation was the shock army, which acted either in co-operation with others or independently as part of a strategic front operation. Several shock armies would be subordinated to a strategic front. Triandafillov created this layout of force allocation for deep operations in his Character of Operations of Modern Armies, which retained its utility throughout the 1930s. Triandafillov assigned the shock army some 12–18 rifle divisions, in four to five corps. These units were supplemented with 16–20 artillery regiments and 8–12 tank battalions. By the time of his death in 1931, Triandafillov had submitted various strength proposals which included the assignment of aviation units to the front unit. This consisted of two or three aviation brigades of bomber aircraft and six to eight squadrons of fighter aircraft.[22]

Triandafillov's successor, Varfolomeev, was less concerned with developing the quantitative indices of deep battle but rather with the mechanics of the shock army's mission. Varfolomeev termed this as "launching an uninterrupted, deep and shattering blow" along the main axis of advance. Varfolomeev believed the shock army needed both firepower and mobility to destroy both enemy tactical defences, operational reserves and seize geographical targets or positions in harmony with other operationally independent and strategically collaborative, offensives.[23]

Varfolomeev and composition of deep operations

[edit]Varfolomeev noted that deep and echeloned tactical and operational defences should call for equal or similar counter responses from the attacker. That allowed the attacker to deliver a deep blow at the concentrating point. The new technological advances would allow the echelon forces to advance the penetration of the enemy tactical zones quickly, denying the enemy defender the time to establish a new defensive line and bring up reinforcements to seal the breach.[24]

Varfolomeev sought to organise the shock armies into two echelon formations. The first was to be the tactical breakthrough echelon, composed of several rifle corps. These would be backed up by a series of second line divisions from the reserves to sustain the tempo of advance and to maintain momentum pressure upon the enemy. These forces would strike 15–20 km into enemy tactical defences to engage his forward and reserve tactical forces. Once they had been defeated, the Red Army Front was ready to release its fresh, and uncommitted operational forces to pass through the conquered tactical zone and exploit the enemy operational zones.[24]

The first echelon used raw firepower and mass to break the layered enemy defences, but the second echelon operational reserves combined firepower and mobility, which was lacking in the former. Operational units were heavily formed from mechanized, motorised and Cavalry forces. The forces would now seek to envelope the enemy tactical forces as yet-unengaged along the flanks of the breakthrough point. Other units would press on to occupy the operational zones and meet the enemy operational reserves as they moved through his rear to establish a new defence's line. While in the operational rear of the enemy, communications, and supply depots were prime targets for the Soviet forces. With his tactical zones isolated from reinforcements, reinforcements blocked from relieving them, the front would be indefensible. Such a method would instigate operational paralysis for the defender.[24]

In official literature Varfolomeev stated that the forces pursuing the enemy operational depth must advance between 20–25 km a day. Forces operating against the flanks of enemy tactical forces must advance as much as 40–45 km a day to prevent the enemy from escaping.[25]

According to a report by the Staff of the Urals Military district in 1936, a shock army would number 12 rifle divisions; a mechanized corps (from its Stavka operational reserve) and an independent mechanized brigade; three Cavalry divisions; a light-bomber brigade, two brigades of assault aviation, two squadrons of fighter and reconnaissance aircraft; six tank battalions; five artillery regiments; plus two heavy artillery battalions; two battalions of Chemical troops. The shock army would number some 300,000 men, 100,000 horses, 1,668 smaller-calibre and 1,550 medium and heavy calibre guns, 722 aircraft and 2,853 tanks.[26]

Deep operations engagement

[edit]Having organized the operational forces and secured a tactical breakthrough into the operational rear of the enemy front, several issues took shape about how the Red Army would engage the main operational enemy forces. Attacking in echelon formation denied the Soviet forces the chance to bring all their units to bear. That might lead to the defeat of a shock army against a superior enemy force.[27]

To avoid such a situation, echelon forces were to strike at the flanks of enemy concentrations for the first few days of the assault, while the main mobile forces caught up. The aim of this was to avoid a head-on clash and tie down enemy forces from reaching the tactical zones. The expected scope of the operation could be 150–200 km.[28]

If the attack proved successful at pinning the enemy in place and defeating its forces in battle, mechanized forces would break the flank and surround the enemy with infantry to consolidate the success. As the defender withdrew, mechanized cavalry and motorised forces would harass, cut off, and destroy his retreating columns which would also be assaulted by powerful aviation forces.[28]

The pursuit would be pushed as far into the enemy depth as possible until exhaustion set in. With the tactical zones defeated, and the enemy operational forces either destroyed or incapable of further defence, the Soviet forces could push into the strategic depth.[28]

Logistics

[edit]The development of Soviet operational logistics, the complex of rear service roles, missions, procedures, and resources intended to sustain military operations by army and front groupings) clearly occupied a prominent place within overall Soviet efforts to formulate or adapt warfighting approaches to new conditions. As Soviet military theorists and planners have long emphasised, logistic theory and practice are shaped by the same historical and technological developments that influence Soviet warfighting approaches at every level. In turn, they play a major role in defining directions and parameters for Soviet methods.

Soviet theory recognised the need for logistic theory and practice that were consistent with other components of strategy, operational art, and tactics. Despite the many changes in the political, economic, and military environment and the quickening pace of technological change, logistical doctrine was an important feature of Soviet thinking.

Intended outcomes; differences with other methodologies

[edit]During the 1930s, the resurgence of the German military in the era of the Third Reich saw German innovations in the tactical arena. The methodology used by the Germans in the Second World War was named by others blitzkrieg. There is a common misconception that blitzkrieg, which is not accepted as a coherent military doctrine,[citation needed] was similar to Soviet deep operations. The only similarities of the two doctrines were an emphasis on mobile warfare and offensive posture.

Both similarities differentiated the doctrines from French and British doctrine of the time. Blitzkrieg emphasized the importance of a single strike on a Schwerpunkt (focal point) as a means of rapidly defeating an enemy; deep battle emphasized the need for multiple breakthrough points and reserves to exploit the breach quickly. The difference in doctrine can be explained by the strategic circumstances for the Soviet Union and Germany at the time. Germany had a smaller population but a better-trained army, and the Soviet Union had a larger population but a less-trained army. As a result, Blitzkrieg emphasized narrow front attacks in which quality could be decisive, but deep battle emphasized wider front attacks in which quantity could be used effectively[citation needed].

In principle, the Red Army would seek to destroy the enemy's operational reserves and its operational depth and occupy as much of his strategic depth as possible. Within the Soviet concept of deep operations was the principle of strangulation if the situation demanded it, instead of physically encircling the enemy and destroying him immediately. Triandafillov stated in 1929 that,

The outcome in modern war will be attained not through the physical destruction of the opponent but rather through a succession of developing manoeuvres that will aim at inducing him to see his ability to comply further with his operational goals. The effect of this mental state leads to operational shock or system paralysis, and ultimately to the disintegration of his operational system. The success of the operational manoeuvre is attained through all-arms combat (combined arms) at the tactical level, and by combining a frontal holding force with a mobile column to penetrate the opponent's depth at the operational level. The element of depth is a dominant factor in the conduct of deep operations both in the offensive and defensive.[29]

The theory moved away from the Clausewitzian principle of battlefield destruction and the annihilation of enemy field forces, which obsessed the Germans. Instead deep operations stressed the ability to create conditions whereby the enemy loses the will to mount an operational defence.[30] An example of the theory in practice is Operation Uranus in 1942. The Red Army in Stalingrad was allocated enough forces to hold the German Sixth Army in the city, which caused attrition that would force it to weaken its flanks to secure its centre. Meanwhile, reserves were built up, which then struck at the weak flanks. The Soviets broke through the German flanks, exploited the operational depth, and closed the pocket at Kalach-na-Donu.

The operation left the German tactical zones largely intact, but by occupying the German operational depth and preventing their retreat the German Army forces were isolated. Instead of reducing the pocket immediately, the Soviets tightened their grip on the enemy forces and preferred to let the enemy weaken and surrender, starve him completely, or a combination of those methods before they delivered a final destructive assault. In that way, the Soviet tactical and operational method opted to besiege the enemy into submission, rather than destroy it physically and immediately.

In that sense, the Soviet deep battle, in the words of one historian, "was radically different to the nebulous 'blitzkrieg'" method but produced similar, if more strategically-impressive, results.[31]

Impact of purges

[edit]Deep operations were first formally expressed as a concept in the Red Army's "Field Regulations" of 1929 and more fully developed in the 1935 Instructions on Deep Battle. The concept was finally codified by the army in 1936 in the Provisional Field Regulations of 1936. By 1937, the Soviet Union had the largest mechanized army in the world and a sophisticated operational system to operate it.

However, the death of Triandafillov in an airplane crash and the Great Purge of 1937 to 1939 removed many of the leading officers of the Red Army, including Svechin, Varfolomeev and Tukhachevsky.[32] The purge of the Soviet military liquidated the generation of officers that had given the Red Army the deep battle strategy, operations and tactics and who also had rebuilt the Soviet armed forces. Along with those personalities, their ideas were also dispensed with.[33] Some 35,000 personnel, about 50 percent of the officer corps, three out of five marshals; 13 out of 15 army group commanders; 57 out of 85 corps commanders; 110 out of 195 division commanders; 220 out of 406 brigade commanders were executed, imprisoned or discharged. Stalin thus destroyed the cream of the personnel with operational and tactical competence in the Red Army.[34] Other sources state that 60 out of 67 corps commanders, 221 out of 397 brigade commanders, 79 percent of regimental commanders, 88 percent of regimental chiefs of staff, and 87 percent of all battalion commanders were excised from the army by various means.[35]

Soviet sources admitted in 1988:

In 1937–1938 ...all commanders of the armed forces, members of the military councils, and chiefs of the political departments of the military districts, the majority of the chiefs of the central administrations of the People's Commissariat of Defense, all corps commanders, almost all division and brigade commanders, about one-third of the regimental commissars, many teachers of higher or middle military and military-political schools were judged and destroyed.[36]

The deep operation concept was thrown out of Soviet military strategy, as it was associated with the denounced figures that created it.

World War II

[edit]

The Soviets consider that armored forces are most effectively employed in the enemy operational depth. After intensive artillery preparation, the infantry assault penetrates into enemy defenses. Then, armored forces strike in the direction of the deepest infantry penetration on a narrow front from a concealed centralized position, develop the breakthrough, and strike at the enemy's rear to destroy him. The scale of operations may reach mammoth proportions as in the breakthrough of German defenses on the River Oder by some 4,000 tanks supported by 5,000 planes on a 50-mile front. Large Red Army armored forces advanced as far as 125 miles in 3 days under conditions of continuous and intensive combat against the German Army.

The abandonment of deep operations had a huge impact on Soviet military capability. Fully engaging in the Second World War (after the Winter War) after Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Soviets struggled to relearn the concept. The surprise German invasion (Operation Barbarossa) subjected the Red Army to six months of disasters. The Red Army was shattered during the first two months. It then faced the task of surviving, reviving and maturing into an instrument that could compete with the Wehrmacht and achieve victory.

Soviet military analysts and historians divide the war into three periods. The Red Army was primarily on the strategic defensive during the first period of war (22 June 1941 – 19 November 1942). By late 1942, the Soviets had recovered sufficiently to put their concept into practice. The second period of war (19 November 1942 – 31 December 1943), which commenced with the Soviet strategic counteroffensive at Stalingrad, was a transitional period marked by alternating attempts by both sides to secure strategic advantage. After that, deep battle was used to devastating effect, allowing the Red Army to destroy hundreds of Axis divisions. After the Battle of Kursk, the Soviets had firmly secured the strategic initiative and advanced beyond the Dnepr River. The Red Army maintained the strategic initiative during the third and final period of war (1944–1945) and ultimately played the central role in the Allied victory in Europe.[37]

Moscow counteroffensive

[edit]Deep battle plan

[edit]Operation Barbarossa had inflicted a series of severe defeats on the Red Army. The German Army Group North was besieging Leningrad, the Army Group South was occupying most of Ukraine and threatening Rostov-on-Don, the key to the Caucasus, and Army Group Centre had launched Operation Typhoon and was closing in on Moscow. The Stavka halted the Northern and Southern Army Groups but was confronted with the German forces approaching the Soviet capital. The Soviet strategy was the defence of the capital and if possible, the defeat and destruction of Army Group Centre. By late November the German pincers either side of the capital had stalled. The Stavka decided to launch a counter offensive. The operational goals were to strike into the enemy operational rear and envelop or destroy the German armies spearheading the attack on Moscow. It was hoped a thrust deeper into the German rear would induce a collapse of Army Group Centre.

Outcome

[edit]Soviet rifle forces penetrated German tactical defenses and pushed into the operational depths on foot at slow speed. They were, however, deficient in staying power. Soon, growing infantry casualties brought every advance to an abrupt end. Soviet cavalry corps reinforced by rifle and tank brigades also penetrated into the German operational rear. Once there and reinforced by airborne or air-landed forces, they ruled the countryside, forests, and swamps but were unable to drive the more mobile Germans from the main communications arteries and villages. At best, they could force limited German withdrawals but only if in concert with pressure from forces along the front. At worst, these mobile forces were themselves encircled, only to be destroyed or driven from the German rear area when summer arrived.

No encirclements ensued, and German forces halted the Soviet advance at the Mius River defenses. South of Moscow, the Red Army penetrated into the rear of the Second Panzer Army and advanced 100 kilometers deep into the Kaluga region. During the second phase of the Moscow counter offensive in January 1942, the 11th, 2nd Guards, and 1st Guards Cavalry Corps penetrated deep into the German rear area in an attempt to encircle German Army Group Center. Despite the commitment into combat of the entire 4th Airborne Corps, the cavalry corps failed to link up and became encircled in the German rear area. The ambitious Soviet operation failed to achieve its ultimate strategic aim, due largely to the fragile nature of Soviet operational mobile forces.

Rzhev–Vyazma offensive

[edit]Deep battle plan

[edit]The Stavka judged that these operations had failed because of the Red Army's lack of large, coherent, mechanized, and armored formations capable of performing sustained operational maneuver. To remedy the problem, in April 1942 the Soviets fielded new tank corps consisting of three tank brigades and one motorized rifle brigade, totaling 168 tanks each. The Stavka placed these corps at the disposal of army and front commanders for use as mobile groups operating in tandem with older cavalry corps, which by now had also received a new complement of armour. The Stavka employed these new tank corps in an offensive role for the first time in early 1942.

During this time, the Germans launched Operation Kremlin, a deception campaign to mislead the Stavka into believing that the main German attack in the summer would be aimed at Moscow. The Stavka were convinced that the offensive would involve Army Group South as a southern pincer against the Central Front protecting Moscow. To preempt the German assault, the Red Army launched two offensive operations, the Rzhev–Vyazma strategic offensive operation against Army Group Centre and the Kharkov offensive operation (known officially as the Barvenkovo-Lozovaia offensive)[38] against Army Group South. Both were directly linked as a spoiling offensives to break up and exhaust German formations before they could launch Operation Blue.[39] The Kharkov operation was designed to attack the northern flank of German forces around Kharkov, to seize bridgeheads across the Donets River north east of the city. A southern attack would be made from bridgeheads seized by the winter-counter offensive in 1941. The operation was to encircle the 4th Panzer army and the 6th Army as they advanced towards the Dnepr river.[40] The operation led to the Second Battle of Kharkov.

The battlefield plan involved the Soviet South Western Front. The South Western Front was to attack out of bridgeheads across the Northern Donets River north and south of Kharkov. The Soviets intended to exploit with a cavalry corps (the 3rd Guards) in the north and two secretly formed and redeployed tank corps (the 21st and 23rd) and a cavalry corps (the 6th) in the south. Ultimately the two mobile groups were to link up west of Kharkov and entrap the German Sixth Army. Once this was achieved, a sustained offensive into Ukraine would enable the recovery of industrial regions.

Outcome

[edit]In fact, primarily due to Stalin's overriding his subordinates' suggestions, the Stavka fell for the German ruse. Instead of attacking the southern pincer of the suspected Moscow operation, they ran into heavy concentrations of German forces that were to strike southward to the Soviet oilfields in the Caucasus, the actual aim of Operation Blue. Although the offensive surprised the Wehrmacht, the Soviets mishandled their mobile forces. Soviet infantry penetrated German defences to the consternation of the German commanders, but the Soviets procrastinated and failed to commit the two tank corps for six days. The corps finally went into action on 17 May simultaneously with a surprise attack by the 1st Panzer Army against the southern flank of the Soviet salient. Over the next two days, the two tank corps disengaged, retraced their path, and engaged the new threat. But it was too late. The German counterattack encircled and destroyed the better part of three Soviet armies, the two tank corps and two cavalry corps, totaling more than 250,000 men.[41] The Kharkov debacle demonstrated to Stalin and Soviet planners that they not only had to create larger armoured units, but they also had to learn to employ them properly.

Operation Uranus and Third Kharkov

[edit]Deep battle plan

[edit]

The Battle of Stalingrad, by October 1942, was allowing the Soviets an ever tighter grip on the course of events. Soviet strategy was simple: elimination of the 6th Army and the collapse of Army Group South. By drawing the German Army into the city of Stalingrad, they denied them the chance to use their greater experience in mobile warfare. The Red Army was able to force its enemy to fight in a limited area, hampered by the city landscape, unable to use its mobility or firepower as effectively as in the open country. The 6th Army was forced to endure severe losses, which forced the OKW to strip its flanks to secure its centre. This left its poorly equipped Axis allies to defend its centre of gravity—its operational depth. When Soviet intelligence had reason to believe the Axis front was at its weakest, it would strike at the flanks and encircle the Germans (Operation Uranus). The mission of the Red Army, then, was to create a formidable barrier between the cut off German army and any relief forces. The aim of the Soviets was to allow the German army to weaken in the winter conditions and inflict attrition on any attempt by the enemy to relieve the pocket. When it was judged the enemy had weakened sufficiently, a strong offensive would finish the enemy field army off. These siege tactics would remove enemy forces to their rear.[29]

Having practised the deep battle phase which would destroy the enemy tactical units (the enemy corps and divisions) as well as the operational instrument, in this case the Sixth Army itself, it would be ready to launch the deep operation, striking into the enemy depth on a south-west course to Rostov using Kharkov as a springboard. The occupation of the former would enable the Red Army to trap the majority of Army Group South in the Caucasus. The only escape route left, through the Kerch Peninsula and into Crimea, would be the next target. The operation would enable the Red Army to roll up the Germans' southern front, thereby achieving its strategic aim. The operation would be assisted by diversion operations in the central and northern sector to prevent the enemy from dispatching operational reserves to the threatened area in a timely fashion.

Outcome

[edit]

Operation Uranus, the tactical deep battle plan, worked. However, the General Staff's deep operation plan was compromised by Joseph Stalin himself. Stalin's impatience forced Stavka into offensive action before it was ready. Logistically the Soviets were not yet prepared and the diversion operations further north were not yet ready to go into action.

Nevertheless, Stalin's orders stood. Forced into premature action, the Red Army was able to concentrate enough forces to create a narrow penetration toward Kharkov. It was logistically exhausted and fighting an enemy that was falling back on its rear areas. The lack of diversionary operations allowed the German Army to recognise the danger, concentrate powerful mobile forces, and dispatch sufficient reserves to Kharkov. With the Red Army's flanks exposed, the Germans easily pinched off the salient and destroyed many Soviet formations during the Third Battle of Kharkov.

The concept of the deep operation had not yet been fully understood by Stalin. However, Stalin recognised his own error, and from this point onward, stood back from military decision-making for the most part. The defeat meant the deep operation would fail to realise its strategic aim. The Third Battle of Kharkov had demonstrated the importance of diversion, or Maskirovka operations. Such diversions and deception techniques became a hallmark of Soviet offensive operations for the rest of the war.

Kursk

[edit]Deep battle plan

[edit]For the first time in the war, at Kursk the Soviets eschewed a preemptive offensive and instead prepared an imposing strategic defense, unparalleled in its size and complexity, in order to crush the advancing Germans. Once the German offense stalled, Soviet forces planned to go over to the offensive at Kursk and in other sectors. The script played as the Soviets wrote it. The titanic German effort at Kursk failed at huge cost, and a wave of Soviet counteroffensives rippled along the Eastern Front ultimately driving German forces through Smolensk and Kharkov back to the line of the Dnepr River.

The Battle of Kursk combined both the defensive and offensive side of deep battle. The nature of Soviet operations in the summer, 1943 was to gain the initiative and to hold it indefinitely. This meant achieving permanent superiority in the balance of forces, in operational procedure and maintaining initiative on the battlefield.[42]

The Soviet plan for the defence of the city Kursk involved all three levels of warfare coherently fused together. Soviet strategy, the top end of military art, was concerned with gaining the strategic initiative which would then allow the Red Army to stage further military operations to liberate Soviet territory lost in 1941 and 1942. To do this, the Stavka decided to achieve the goal through defensive means. The bulge in the front line around Kursk made it an obvious and tempting target to the Wehrmacht. Allowing the Germans to strike first at the target area allowed the Red Army the opportunity to wear down German Army formations against pre-prepared positions, thereby shaping the force in field ratio heavily against the enemy. Once the initiative had been achieved and the enemy had been worn down, strategic reserves would be committed to finish off the remaining enemy force. The success of this strategy would allow the Red Army to pursue its enemy into the economically rich area of Ukraine and recover the industrial areas, such as Kiev, which had been lost in 1941. Moreover, Soviet strategists recognised that Ukraine offered the best route through which to reach Germany's allies, such as Romania, with its oilfields, vital to Axis military operations. The elimination of these allies or a successful advance to their borders would deny Germany military resources, or at least destabilise the Axis bloc in the Balkans.

The operational method revolved around outmanoeuvring their opponents. The nature of the bulge meant the Red Army could build strong fortifications in depth along the German axis of advance. Two rifle divisions defended the first belt, and one defended the second. A first belt division would only defend an area of 8–15 kilometres wide and 5–6 kilometres in depth.[43] Successive defence belts would slow German forces down and force them to conduct slow and attritional battles to break through into the operational depths. Slowing the operational tempo of the enemy would also allow the Soviet intelligence analysts to keep track of German formations and their direction of advance, enabling Soviet reserve formations to be accurately positioned to prevent German spearheads breaking through each of the three main defence belts. Intelligence would also help when initiating their own offensives (Operation Kutuzov and Operation Polkovodets Rumyantsev) once the Germans had been bogged down in Soviet defences. The overwhelming contingent of Soviet armour and mechanised divisions was given to the operational reserves for this purpose.[44]

The tactical level relied heavily on fortified and static defences composed of infantry and artillery. Anti-tank guns were mounted throughout the entire depth of the defences. Few tanks were committed to the tactical zones and the nature of the defences would have robbed them of mobility. Instead, only a small number of tanks and self-propelled artillery were used to give the defences some mobility. They were distributed in small groups to enable localised counterattacks.[45] Such tactics slowed the Germans, forcing them to expend strength and munitions on combating the Soviet forward zones. The Soviets had counted on the Germans being stopped within the tactical zones. To ensure that this occurred, they distributed large numbers of anti-AFV (armoured fighting vehicle) and anti-personnel mines to the defences.

Outcome

[edit]During the exploitation period, mechanized units encounter the enemy's tactical reserves and also rear reserves rushed up by motor, rail, or even air. Therefore, in the process of exploitation mechanized units have to carry out bitter actions, sometimes to defend themselves, sometimes to disengage themselves. All actions are carried out with the following goals in mind: to retain the initiative, to defeat the pursued enemy in detail, and to surround and destroy his reserves after cutting them off. The job of complete liquidation is left to regular front-line troops, while the mechanized units go on to exploit the new success.

The Germans began their offensive, as predicted, on 5 July 1943, under the codename Operation Citadel. The Soviets succeeded in limiting them to a slow advance. In the north, the 9th Army advanced south from Orel. The Germans failed to breach the main defence lines, stalling at the third belt. The German armies had been forced to commit their mobile reserves to the breakthrough. This allowed the Soviets to conduct the operational and offensive phase of their plan; Operation Kutuzov. Striking the 2nd Panzer Army, the Soviet's fresh operational forces, heavily mechanized, threatened to cut off the 9th Army. Had they succeeded, nothing would have stood between the Red Army and the strategic depth of the front of Army Group Centre. The Germans were able to stem the advance by committing their mobile reserves and organize a withdrawal. Still, the two German armies had been worn down, and the Soviet forces in the north had won the strategic initiative.

In the south, the Soviet plan did not work as effectively and the contingency plan had to be put into effect. The German formations succeeded in penetrating all three Soviet defence belts. This denied the Soviets the opportunity to pin them down in the tactical defence belts and release their operational reserves to engage the enemy on favourable terms. Instead, operational forces for Operation Polkovodets Rumyantsev that were intended for the southern counteroffensive, were ordered to at and near Prokhorovka. This led to the Battle of Prokhorovka. While the tactical deployment and operational plan had not worked as flawlessly as it had in the north, the strategic initiative had still been won.

Other campaigns

[edit]With improved material means and tactical aptitude enabling complicated large-unit maneuvers, the following later campaigns were able to exhibit an improved application of the Deep operation doctrine:

Cold War

[edit]Central Europe

[edit]The Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies used their massive superiority in numbers and the idea of Deep Battle to intimidate NATO over the Inner German border. Some Western observers predicted that the Warsaw Pact could use a mixture of speed and surprise to overrun Western Europe in around 48 hours. While massive air strikes using enormous numbers of aircraft would devastate NATO infrastructure and reinforcements, VDV (airborne units), Spetsnaz ("special purpose troops", i.e. special forces) and naval infantry would clear the way for the torrent of tank and motor-rifle divisions that would soon cross the border. The forward units of these tank and motor rifle divisions would be given the task, rather unusually, of avoiding engagements with the enemy and simply to advancing as far and as fast as possible, therefore enabling a victory before any replacement aircraft and Reforger units came to Europe from North America.

Asia

[edit]Ever since the 1960s when the Sino-Soviet alliance came to an abrupt end, the Soviet High Command considered invading China by deep battle offensive operations, envisaging a rapid drive deep towards the latter's main industrial centers before they could have a chance to mount a credible defense or even stage a counterattack. The vast numbers of the Chinese People's Liberation Army and their knowledge of the terrain, coupled with their then-recent possession of nuclear weapons, made such a drive the Soviets were to execute extremely unlikely. Although both sides nearly went to war in three separate occasions in 1968, 1969 and 1979 respectively, the Soviets were rather hesitant to go to war and invade China, thanks to the fact that both possessed huge armed forces and nuclear weapons at their disposal.

21st century

[edit]In the spring of 1999 came the crisis in Kosovo and the NATO Operation Allied Force as a result of R2P doctrine. The combat operations featured no land warfare and no front line can be said to have existed. The air war over Serbia was a "deep battle" as the Air Force bombed strategic targets and fielded forces. Major General Robert H. Scales came to the conclusion that the US needed "strategic pre-emption", defined as the "use of airpower to delay the enemy long enough for early arriving ground forces to position themselves between the enemy and his initial operational objectives."[46]

Major proponents

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Simpkin, Richard E. (1987). Deep battle: The brainchild of Marshal Tuchachevskii. London: Bassey's Defence Publishers. p. 24. ISBN 0-08-031193-8.

- ^ Harrison 2001, p. 4.

- ^ Harrison 2001, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Cody and Krauz 2006, p. 229.

- ^ Harrison 2001, p. 123.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (1921). "Military Doctrine or Pseudo-Military Doctrinairism". Marxist Internet Archive. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ a b Harrison 2001, p. 126.

- ^ Harrison 2001, pp. 129–131.

- ^ a b Harrison 2001, p. 140.

- ^ Harrison 2001, pp. 187–194.

- ^ Harrison 2001, p. 187.

- ^ Watt 2008, p. 673–674.

- ^ Glantz 1991a, p. 40.

- ^ a b Harrison 2001, p. 193.

- ^ https://www.ausa.org/sites/default/files/LWP-56-Mikhail-Nikolayevich-Tukhachevsky-1893-1937-Practitioner-and-Theorist-of-War.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b c Harrison 2001, p. 204.

- ^ a b Harrison 2001, p. 205.

- ^ Harrison 2001, p. 189.

- ^ a b Harrison 2001, p. 190.

- ^ a b Glantz 1991a, p. 124.

- ^ a b c d Harrison 2001, p. 194.

- ^ a b Harrison 2001, p. 195.

- ^ Harrison 2001, p. 196.

- ^ a b c Harrison 2001, p. 197.

- ^ Harrison 2001, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Harrison 2001, p. 198.

- ^ Harrison 2001, p. 199.

- ^ a b c Harrison 2001, p. 200.

- ^ a b Watt 2008, p. 677.

- ^ Watt 2008, p. 675.

- ^ Watt 2008, pp. 677–678.

- ^ Glantz 1991a, p. 25.

- ^ Glantz 1991a, p. 89.

- ^ Glantz 1991a, p. 88.

- ^ Harrison 2001, p. 220.

- ^ Glantz 1991a, p. 89: "Pomnit' uroki istorii. Vsemerno ukrepliat' boevuiu gotovnost'" – Remember the Lessons of History. Strengthen Combat Readiness in every possible way, VIZh, No. 6, 1988, 6.

- ^ Glantz in Krause and Phillips 2006, p. 248.

- ^ Krause and Phillips 2006, p. 250

- ^ Glantz & House 1995, p. 106.

- ^ Glantz & House, p. 106.

- ^ Krause and Phillips 2006, p. 251.

- ^ V.M Kulish 1974, p. 168.

- ^ Glantz 1991a, p. 135.

- ^ Watt 2008, pp. 675, 677.

- ^ Glantz 1991a, p. 136.

- ^ Grant 2001.

Bibliography

[edit]- Glantz, David M., Col (rtd.) Soviet Military Operational Art: In Pursuit of Deep Battle, Frank Cass, London, 1991a. ISBN 0-7146-4077-8.

- Glantz, David M. (1991b). The Soviet Conduct of Tactical Maneuver: Spearhead of the Offensive (1. publ. ed.). London u.a.: Cass. ISBN 0-7146-3373-9.

- Grant, Rebecca (1 June 2001). "Deep Strife". Air & Space Forces Magazine.

- Habeck, Mary. Storm of Steel: The Development of Armor Doctrine in Germany and the Soviet Union, 1919–1939. Cornell University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8014-4074-2

- Harrison, Richard W. The Russian Way of War: Operational Art 1904–1940. Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas, 2001. ISBN 0-7006-1074-X

- Krause, Michael and Phillips, Cody. Historical Perspectives of Operational Art. Center of Military History, United States Army. 2006. ISBN 978-0-16-072564-7

- Naveh, Shimon (1997). In Pursuit of Military Excellence; The Evolution of Operational Theory. London: Francass. ISBN 0-7146-4727-6.

- Simpkin, Richard. Deep Battle: The Brainchild of Marshal Tukhachevsky. London; Washington: Brassey's Defence, 1987. ISBN 0-08-031193-8.

- Watt, Robert. Feeling the Full Force of a Four Point Offensive: Re-Interpreting The Red Army's 1944 Belorussian and L'vov-Przemyśl Operations. The Journal of Slavic Military Studies. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. ISSN 1351-8046

External links

[edit]- Blythe, Wilson C. Jr. "The Conduct of War: Reemergence of Russian Military Strength Warrants Study of Soviet Operational Theory in the Interwar Era", in The Officer (Winter 2015), accessible online at: https://www.academia.edu/31966162/The_Conduct_of_War_Re_emergence_of_Russian_Military_Strength_Warrants_Study_of_Soviet_Operational_Theory_in_the_Interwar_Era

- The Evolution of Operational Art by Georgii Isseson, 1936 – PDF, available on United States Army Combined Arms Center's website

- "Georgii Isserson: Architect of Soviet Victory in World War II": Video on YouTube, a lecture by Dr. Richard Harrison, via the official channel of the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center