Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Duende

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A duende is a humanoid figure of folklore, with variations from Iberian, Ibero American, and Latin American cultures, comparable to dwarves, gnomes, or leprechauns.

Etymology

[edit]In Spanish, duende originated as a contraction of the phrase dueñ(o) de casa, effectively "master of the house", or alternatively, derived from some similar mythical being of the Visigoth or Swabian culture given its comparable looks with the “Tomte” of the Swedish language conceptualized as a mischievous spirit inhabiting a dwelling.[1]

Spain

[edit]Spanish folklore is rich in tales and legends about various types of duendes: Anjanas, Busgosos, Diaños, Enanos, Elfos, Hadas, Nomos, Nuberus, Tentirujus, Trasgos/Trasgus, Trastolillus, Trentis, Tronantes, Ventolines and others. In some regions of Spain, duendes may have other names like Trasnos in Galicia, Follets in Catalonia, Iratxoak in the Basque Country and Navarra, Trasgus in Asturias, Menutos or Mendos in Valle de Hecho and in other parts of Alto Aragón, Mengues (South of Spain).

Anjanas

[edit]Anjanas in Cantabria, Xanas in Asturias, and Janas in Castille and Leon are duendes similar to the nymphs of Ancient Greece. They are described as extremely beautiful beings with long flowing hair that they comb daily for long hours. Anjanas clothe themselves with dresses made up of stars or stardust and wear fabulous pearls. They are known to wear floral crowns and walk with floral staffs. Depending on the region, anjanas may be usually small in size—not much larger than a flower—but may change their size to be as large as mortal humans or even taller. In other regions, anjanas are as tall as humans.[2]

Anjanas are said to live in fountains, springs, rivers, ponds, lakes and caves and come out only at night when humans are sleeping.[2] Their homes are said to hold bountiful treasures that they protect and may use to help those that truly need them. Anjanas are never malignant but always benign. They help humans and creatures running away from nasty ogre-like beings called ojancanus. They bless the waters, the trees, the farms and herds.[2]

It is said that a man that finds an anjana brushing her hair can marry her and take possession of all her bountiful treasures. However, if the man is unfaithful, she will disappear forever with all her treasures, and the man shall remain destitute for the rest of his life.

In Galicia and Portugal, a similar mythological being to the Anjanas or Xanas is called a Moura.

Apabardexu

[edit]In the Lakes of Somiedo, locals say there lives a kind of mountain duende. In Asturleonese, apabardexu may translate to duende of the mountain or of the lake.[3]

Busgosos

[edit]Busgosos, also known as musgosos, are tall bearded duendes dressed in moss and leaves. They play sad songs on their flutes to help guide shepherds through forests. They are compassionate and hardworking. They will repair the barns and homes of humans that have collapsed due to the weather.[2]

Diaños

[edit]Diaños are mischievous duendes that adopt the figure of horses, cows, rams or any other domestic animal, even a human baby. They are active during the night, scaring those who walk at odd hours, and disorient peasants searching for their lost cattle. They annoy millers who mill in the moonlight and mock waiters who return late from parties. Among their most common antics is turning into a white donkey and offering themselves as a mount to passerby; once mounted, they grow and grow incessantly. Similarly, they become a horse and after a hellish gallop return the rider to the same place from which it started. As cold and wet goats, they mock a benefactor that brings them home to dry and warm up close to a fire. As a black dog, they chase a person on foot. As toads, they run faster than horses. They love to turn into babies that play naked in the snow. They may also be the cause of endless noises, mysterious lights and other disturbing phenomena that frighten those who walk at night[citation needed].

Enanos

[edit]Enanos (dwarfs in English) are diminutive beings that toil night and day in the forests, guard the immense riches that the subterranean world hides, and, mockingly, tempt the greed of peasants by offering him gold combs, bags full of silver, which later become piles of withered fern leaves and white pebbles. Some enanos, like the Duende de los Extravios, help good people find their lost possessions.[2]

Elf

[edit]Elfos (elves in English) are probably not pre-Roman mythological beings of the Iberian Peninsula but instead were brought in by Germanic tribes (Vandals, Suevi and Visigoths) that settled into Spain during Roman period and after the fall of Rome. The oldest mention of Elfos are in the famous Cantar de Mio Cid, a medieval tale of a Castillian knight named Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar, known best as El Cid. Elfos have very similar characteristics of Anjanas and were most likely readily taken up by locals as such.

Hadas

[edit]Hadas (fades in Catalan, fadas in Galician-Portuguese) are the Hispanicized Roman fatas (feminine plural of fatum). The fatum in Roman times were personifications of destiny. Hadas used interchangeably with the Anjanas or used as a general word to describe all sorts of mythological beings, not only duendes but also ogres, sirenas (mermaids) and others, similar to how English speakers use the word fairy[citation needed].

Nuberos

[edit]Nuberos may be good or malignant duendes in the form of clouds said to have the ability to make it rain, hail, and snow. The bells of villages and towns can conjure nuberos with the sad song of the tente-nu.[2]

Tentirujus

[edit]Tentirujus are small malignant duendes that dress in red and turn obedient and good children (particularly girls) into bad and disobedient ones. They do so using the secret powers of the mandrake, a magical plant with roots in the form of humans.[2]

Trasgos

[edit]Trasgos are among the most hated of duendes. They are mischievous creatures. They love to enter people's homes through chimneys and live within the hidden spaces of a home. They move things around or out right steal things from the homes they inhabit so they are forever lost. They love to climb up trees and throw pebbles, seeds, and branches at people. They may turn good boys into mischievous ones. Boys who are improperly raised may even become trasgos themselves.[2]

Trastolillos

[edit]Trastolillos are small duendes that live in the dwellings of man. They make wheat flour in troughs bloom back into wheat forcing farmers to remill them into flour. They love to drink milk and will drink all the stores of milk. They also open windows during windy storms and cause stews to overcook and burn. They will apologize for the damage they have done but cannot help themselves and will do it again.[2]

Trentis

[edit]Trentis are small duende being either made up of or clothed in leaves, moss, roots and twigs. They are said to live in thick hedges and love playing pranks on people. They are known to pull down the skirts of women and pinch them in their buttocks.[2]

Tronantes

[edit]Tronantes translates to "thunderers." These duendes have the ability to make thunder and lightning[citation needed].

Ventolines

[edit]Ventolines are good fairy-like duendes with large green wings. They live on the ocean and help old fishermen to row their boats at sea.[2]

Castilian duendes

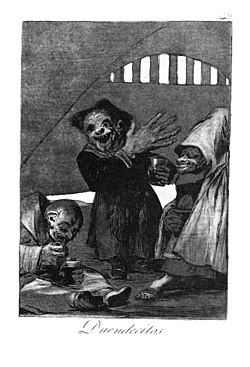

[edit]It is possible to distinguish between the Spanish and the Castilian duendes. Castilian duendes usually take the form of Martinicos, diaños, trasgos, gnomes, enchanted women, fairies, and elves. The Martinicians, bogged down with the bestiones of the Middle Ages and engraved in some of Goya's Caprichos, are big-headed dwarfs (represented as big heads in popular festivals) with big hands and are usually disguised with a Franciscan habit. They make noises in cupboards, move and lose objects, and play cruel jokes. The gnomes inhabit the cavities of the earth[citation needed].

The first mention of an elf in Spanish literature is made in the Cantar de Mio Cid, when it speaks of the "Elfa pipes", that is, Elfa's cave.[4] The first to deal extensively with goblins was the demonologist Fray Antonio de Fuentelapeña in The Elucidated Entity: Unique New Discourse That Shows That There Are Invisible Irrational Animals In Nature (1676). It was said that all the goblins disappeared with the bull of the Holy Crusade. Later, in the eighteenth century, the pre-enlightened Benedictine Father Benito Jerónimo Feijoo engaged in an all-out fight against these superstitions in his Universal Critical Theater[citation needed].

On the other hand, in the flamenco cultural context, the inexplicable and mysterious character that this art and its interpreters acquire on certain occasions is called duende, a mysterious power that everyone feels and no philosopher explains.[5]

Portugal

[edit]Duende also appear in Portuguese folklore, described as beings of small stature wearing big hats, whistling a mystical song, often walking in the forest. Variously rendered in English as "goblins", "pixies", "brownies", "elves", or "leprechauns", the duende use their talents to lure young children to the forest, who lose their way home.

Latin America

[edit]Conversely, in some Latin American cultures, duendes are believed to lure children into the forest. In the folklore of the Central American country of Belize, particularly amongst the country's African/Island Carib-descended Creole and Garifuna populations, duendes are thought of as forest spirits called "Tata Duende" who lack thumbs.[6] The Yucatec Maya of Belize and Southeast Mexico have duendes such as Alux and Nukux Tat which are seen as guardian spirits of the forest.

In the Hispanic folklore of Mexico and the American Southwest, duendes are known as gnome-like creatures who live inside the walls of homes, especially in the bedroom walls of young children. They attempt to clip the toenails of unkempt children, often leading to the mistaken removal of entire toes.[7] Belief in duendes still exists among the Mixtecs and Zapotecs of Oaxaca and it is said that they are most commonly found in the mossy cloud forests of the state's mountain ranges.

In the Andean region of Peru, early colonial accounts recorded local beliefs in forest spirits that Spanish chroniclers equated with duendes or succubi. These beings, called waraqlla, were believed to inhabit sacred alder trees regarded as wak’a. According to Father Antonio de la Calancha, there was a sacred alder grove inhabited by waraqlla close to Tauca, where the spirits were said to manifest through voices and were venerated with great fervor. The people of Tauca were described as deeply devoted to these beings, whom missionaries interpreted as sensual female entities, and priestesses were consecrated to the service of the forest wak’a.[8][9] The name waraqlla, from Quechua, derives from waraq (“dawn”) and the suffix -lla (denoting immediacy), meaning “early dawn” and interpreted as “spirit of the early light.”

Philippines and Mariana Islands

[edit]Filipino people have folklore telling of the dwende, which often dwell in rocks and caves, old trees, unvisited and dark parts of houses, or in anthills and termite mounds.[10] Those that live in the last two are termed nunò sa punsó (Tagalog for “old man of the mound”). They are either categorized as good or evil depending on their color (white or black, respectively), and are often said to play with children (who are more capable than adults of seeing them). Offending a nunò sa punsó is taboo; people who step on them are believed to be cursed by the angered dwende within.

The Chamorro people of the Marianas Islands tell tales of the taotaomo'na, duendes and other spirits. A duende, according to the Chamorro-English Dictionary by Donald Topping, Pedro Ogo and Bernadita Dungca, is a goblin, elf, ghost or spook in the form of a dwarf, a mischievous spirit which hides or takes small children. Some believe the Duende to be helpful or shy creatures, while others believe them to be mischievous and eat misbehaving children.

Art & literature

[edit]- Based on popular usage and folklore, the Spanish poet and playwright Federico García Lorca wrote a treatise on the aesthetics of Duende in popular culture, called "Play and Theory of the Duende" (Argentina, 1933). Lorca's vision of duende includes: irrationality, earthiness, an awareness of death, and a diabolical touch.[11]

- The Duende looms large in both the poetry and Latino philosophy of Giannina Braschi.[12][13] She has written an ars poetica featuring the Duende in Empire of Dreams (i.e., "Poetry is this screaming Madwoman").[14] She has also published a treatise on Lorca's treatment of the Duende,[15] and a lyric essay called "Hierarchy of Inspiration" about artistic inspiration rising from the Duende, Angel, Muse, and Daemon in United States of Banana.[16]

- Pulitzer prize winning poet Tracy K. Smith wrote a book about desire entitled Duende.[17]

- In 1997, electronic artist Delerium released a single entitled "Duende" which featured on their album Karma.[18]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Joan Corominas, 'Breve diccionario etimológico de la lengua', "Duende" (Madrid: Editorial Gredos, 1980).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sainz de la Cotera, Gustavo (2005). La Cantabria de Gustavo Cotera: Mitos, Costumbres, Gentes. Villanueva de Villaescusa: Valnera. ISBN 9788493436636.

- ^ Calleja, Jesus (20 September 2015). "En Somiedo hay un caso para Cuarto Milenio: el 'apabardexu' o duende del lago". cuatro.com. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ F. W. Hodcroft, «Elpha»: nombre enigmático del «Cantar de Mío Cid», en AFA, XXXIV-XXXV, pp. 39-63 http://ifc.dpz.es/recursos/publicaciones/09/23/04hodcroft.pdf

- ^ Federico García Lorca, citando a Goethe, en Teoría y juego del duende

- ^ Emmons (1997).

- ^ See retelling in Garza (2004, pp. 2–11).

- ^ Arriaga, Pablo Joseph de. La extirpación de la idolatría en el Perú. Lima: Imprenta y Librería Sanmarti y Cía, 1920 (originally 1621). Available online at Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes: https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor/la-extirpacion-de-la-idolatria-en-el-peru--0/html/ff49f4c0-82b1-11df-acc7-002185ce6064_16.html#I_0_

- ^ Calancha, Antonio de la. Corónica moralizada del Orden de San Agustín en el Perú. Barcelona: Pedro Lacavalleria, 1638. Available at Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/A050111/page/n5/mode/2up

- ^ Tagalog-English Dictionary by Leo James English, Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer, Manila, distributed by National Book Store, 1583 pages, ISBN 971-91055-0-X

- ^ García Lorca, Federico (2010). In search of duende. Maurer, Christopher., Di Giovanni, Norman Thomas. New York: New Directions. ISBN 978-0-8112-1855-9. OCLC 569568655.

- ^ Horno-Delgado, Asuncion (1994). "Lo inevitable cotidiano, la sorpresa erotizante en la poética de Almudena Guzmán". Iberoromania. 1994 (39). doi:10.1515/iber.1994.1994.39.55. ISSN 0019-0993. S2CID 162339366.

Characters in the guise of el Duende.

- ^ Bécares Rodríguez, Laura (2017-06-24). "Reseña Exposición Temporal: Las Edades de las Mujeres Iberas, la ritualidad femenina en las colecciones del Museo de Jaén". Cuestiones de género: De la igualdad y la diferencia (12): 437. doi:10.18002/cg.v0i12.3923. ISSN 2444-0221.

- ^ "Poetry is This Screaming Madwoman by Giannina Braschi". poets.org. Retrieved 2020-10-27.

- ^ Braschi, Giannina. "Breve tratado del poeta artista". Literatura Hispanoamericana – via Virtual Cervantes.

- ^ Gonzalez, Madelena (2014-06-03). "United States of Banana (2011), Elizabeth Costello (2003) and Fury (2001): Portrait of the Writer as the 'Bad Subject' of Globalisation". Études britanniques contemporaines (46). doi:10.4000/ebc.1279. ISSN 1168-4917.

Hierarchy of Inspiration: the demon, the duende, the angel and the muses

- ^ "Duende by Tracy K. Smith". poets.org. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ "Delerium - Duende". discogs.com. 2024. Retrieved 2024-09-22.

References

[edit]- Emmons, Katherine M. (October 1997). "Perceptions of the Environment while Exploring the Outdoors: a case study in Belize". Environmental Education Research. 3 (3). Ambingdon, Oxfordshire: Carfax Publishing, in conjunction with the University of Bath: 327–344. doi:10.1080/1350462970030306. OCLC 34999650.

- Garza, Xavier (2004). Creepy Creatures and other Cucuys (Piñata Books imprint ed.). Houston, TX: Arte Público Press. ISBN 1-55885-410-X. OCLC 54537415.

.jpg/250px-Goya_-_Caprichos_(49).jpg)

.jpg)