Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

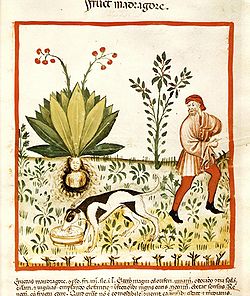

Mandrake

View on WikipediaThis article may require copy editing for Style and cohesion issues throughout. (June 2025) |

A mandrake is one of several toxic plant species with "man-shaped" roots and some uses in folk remedies. The roots by themselves may also be referred to as "mandrakes". The term primarily refers to nightshades of the genus Mandragora (in the family Solanaceae) found in the Mediterranean region. Other unrelated plants also sometimes referred to as "mandrake" include Bryonia alba (the English mandrake, in the family Cucurbitaceae) and Podophyllum peltatum (the American mandrake, in the family Berberidaceae). These plants have root structures similar to members of Mandragora, and are likewise toxic.

This article will focus on mandrakes of the genus Mandragora and the European folklore surrounding them. Because these plants contain deliriant hallucinogenic tropane alkaloids and the shape of their roots often resembles human figures, they have been associated with magic rituals throughout history, including present-day contemporary pagan traditions.[2]

Nomenclature

[edit]The English name "mandrake" derives from Latin mandragora, and while the classical name has nothing to do with either "man" or "dragon/drake", the English form made it susceptible to such a folk etymology.[3] The French form main-de-gloire ("hand of glory") has been held up as an even "more complete example" of folk etymology (cf. § Main-de-gloire).[4]

The German common name is Alraun, Alraune (cf. § Alraun below).[5] However, the Latin mandragora, misidentified by false etymology to have a -draco ("dragon") stem (as manifests in the English from "mandrake", above) has caused the plant and beast to be conflated into an Alraundrachen, in the sense of a household spirit.[6] This combined form is not well attested, but the house kobold is known regionally as either alraune[e] or drak (drak),[a] both classed as "dragon names" by Weiser-Aall (cf. § Alraun-drak).[7]: 68), 71)

The mandrake-doll in German might be called Alraun Männlein ("mandrake manikin"), in Belgian (Flemish) mandragora manneken, or in Italian mandragora maschio.[8] In German, it is also known as Galgenmännlein ("little gallows man") stemming from the belief that they grow near gallows, also attested in Icelandic þjófarót "thieves' root".[9][10]

Certain sources cite the Dutch name pisdiefje (lit. "little urine thief"[b]) or pisduiveltje ('urine devilkin'), claiming the plant grows from the brains of dead thieves, or the droppings of those hung on the gallows.[11][12] The name "brain thief" for mandrake also occurs in English.[11]

Toxicity and pharmaceutical usage

[edit]All species of Mandragora contain highly biologically active alkaloids, tropane alkaloids in particular. The alkaloids make the plant, in particular the root and leaves, poisonous, with anticholinergic, hallucinogenic, and hypnotic effects. Anticholinergic properties can lead to asphyxiation. People can be poisoned accidentally by ingesting mandrake root, and ingestion is likely to have other adverse effects such as vomiting and diarrhea. The alkaloid concentration varies between plant-samples. Clinical reports of the effects of consumption of Mediterranean mandrake include severe symptoms similar to those of atropine poisoning, including blurred vision, dilation of the pupils (mydriasis), dryness of the mouth, difficulty in urinating, dizziness, headache, vomiting, blushing and a rapid heart rate (tachycardia). Hyperactivity and hallucinations occur in the majority of patients.[13][14]

The root is hallucinogenic and narcotic. In sufficient quantities, it induces a state of unconsciousness and was used as an anaesthetic for surgery in ancient times.[15] In the past, juice from the finely grated root was applied externally to relieve rheumatic pains.[15] It was used internally to treat melancholy, convulsions, and mania.[15] When taken internally in large doses it was said to excite delirium and madness.[15]

Ancient Greco-Roman pharmacopoeia

[edit]

Theophrastus (d. c. 287 BC) Historia Plantarum wrote that the mandragora needed to be harvested by following a prescribed ritual, namely, "draw three circles around [the root] with a sword, and cut it facing west"; then in order to obtain a second piece, the harvester must dance around it while speaking as much lewd talk about sex as he possibly can.[19] The ritual given in Pliny probably relies on Theophrastus.[16]

Dioscorides in De materia medica (1st century) described the uses of mandragora as a narcotic, analgesic, and abortifacient. He also claimed a love potion could be concocted from it.[20]

Dioscorides as a practicing physician writes that some in his profession may administer a ladle or 1 cyathus (45 ml (1.5 US fl oz)) of mandrake reduction, made from the root boiled in wine until it shrivels to a third, before performing surgery.[24] Pliny the Elder also repeats that a 1 cyathus dose of mandragora potion is drunk [c] by the patient before incisions or punctures are made on his body.[25][22] A simple juice (ὀπός) can be produced by mashing the root or scoring and leeching out, or a reduction type (χύλισμα, χυλός) made by boiling, for which Dioscorides provides distinguishing terms, though Pliny lumps these into "juice" (sucus). Just the stripped bark may be infused for a longer period, or the fruits can be sun-dried into a condensed juice, and so forth.[26] The plant is supposedly strong-smelling. And its use for eye remedy is also noted.[25]

Both authors acknowledge that there were male and female mandragora.[20] Pliny states there was the white male type and the dark female type of mandragora.[25] However, he also has a different book-chapter on what he presumes to be a different plant called the white eryngium, also called centocapitum, which also are of two types, those resembling the male and female genitalia, which translators note might also be actually referring to the mandragora (of Genesis 30:14).[29] If a man came into possession of a phallic mandrake (eryngium), this had the power to attract women.[29][20] Pliny contends that Phaon of Lesbos Island, by obtaining this phallic root was able to cause the poet Sappho to fall in love with him.[29]

A parallel has been noted between the lore of the mandrake harvested from a hangman, and the unguent which Medea gave to Iason, which was made from a plant fed with the body fluid from chain-bound Prometheus.[32][9]

The ancient Greeks also burned mandrake as incense.[33]

Biblical

[edit]Two references to duḏāʾim (דּוּדָאִים "love plants";[34] singular: duḏā דודא) occur in the Jewish scriptures. The Septuagint translates דודאים as Koine Greek: μανδραγόρας, romanized: mandragóras, and the Vulgate follows the Septuagint. Several later translations into different languages follow Septuagint (and Vulgate) and use mandrake as the plant as the proper meaning in both the Genesis 30:14–16[35] and Song of Songs 7: 12-13.[34] Others follow the example of the Luther Bible and provide a more literal translation.[d]

The dud̲āʾim was considered an aphrodisiac[36] or rather a treatment for infertility,[37][35] as in Genesis 30:14. The anecdote concerns the fertility of the wives of Jacob, who engendered the Twelve Tribes of Israel headed by his many children. Though he had a firstborn son Reuben by Leah which was a marriage forced upon him, his favorite wife Rachel, Leah's younger sister, remained barren and coveted the dudaʾim. This plant was found by the boy Reuben who supposedly entrusted it to Leah, who would barter it in exchange for allowing her to spend a night in Jacob's bed.[39]

However, the herbal treatment does not seem to work on Rachel, and instead, Leah, who had previously had four sons but had been infertile for a long while, became pregnant once more, so that in time, she gave birth to two more sons, Issachar and Zebulun, and a daughter, Dinah.[40] Thus Rachel had to endure several more years of torment being childless, while her sister could flaunt her prolific motherhood, until God intervened, allowing for Rachel's conception of Joseph.[41][37]

The final verses of Chapter 7 of Song of Songs (verses 12–13), mention the plant once again:

נַשְׁכִּ֙ימָה֙ לַכְּרָמִ֔ים נִרְאֶ֞ה אִם פָּֽרְחָ֤ה הַגֶּ֙פֶן֙ פִּתַּ֣ח הַסְּמָדַ֔ר הֵנֵ֖צוּ הָרִמֹּונִ֑ים שָׁ֛ם אֶתֵּ֥ן אֶת־דֹּדַ֖י לָֽךְ׃ הַֽדּוּדָאִ֣ים נָֽתְנוּ-רֵ֗יחַ וְעַל-פְּתָחֵ֙ינוּ֙ כָּל-מְגָדִ֔ים חֲדָשִׁ֖ים גַּם-יְשָׁנִ֑ים דּוֹדִ֖י צָפַ֥נְתִּי לָֽךְ:

Let us get up early to the vineyards; let us see if the vine flourish, whether the tender grape appear, and the pomegranates bud forth: there will I give thee my loves. The mandrakes give a smell, and at our gates are all manner of pleasant fruits, new and old, which I have laid up for thee, O my beloved.

— the Bible, King James Version, Song of Songs 7:12–13[42]

Physiologus

[edit]

In the Christian allegorical bestiary Physiologus, the chapter on the elephant claims that the male becomes minded to create an offspring, it leads its mate to the growing ground for the female to find the mandragora and come into estrous, the female then brings the root to the male which in turn become inflamed and they mate, making the female immediately pregnant.[44][45] The elephants are illustrated in e.g., Sloane 278.[43]

Philippe de Thaun's bestiary in Anglo-Norman verse has a chapter on the "mandragore", which states it consists of two kinds of roots, and must be extracted by the method of using a dog. He proports it to be a cure of all illnesses, save death[46][47]

Josephus

[edit]Josephus (circa 37-100) of Jerusalem instructed on a method of using a dog as surrogate to uproot the dangerous herb used in exorcism. The herb has been equated to the mandragora in subsequent scholarship. According to Josephus, it was no easy task for the harvester, because it will move away from the hand which will grab it, and though it can be stopped by pouring a woman's urine or menstrual blood on it, touching it will cause certain death.[48][20] Thus in order to safely obtain it:

A furrow must be dug around the root until its lower part is exposed, then a dog is tied to it, after which the person tying the dog must get away. The dog then endeavours to follow him, and so easily pulls up the root, but dies suddenly instead of his master. After this, the root can be handled without fear.[34]

Here Josephus only refers to the plant as Baaras, after the place where it grows (in the valley Wadi Zarqa[21] covering the north side of Machaerus,[50] in present-day Jordan), and thinks the plant is a type of rue (of the citrus family)[48] however, it is considered to be identifiable as mandrake based on textual comparisons[51] (cf. § Alraun).

Folklore

[edit]

In the past, mandrake was often made into amulets which were believed to bring good fortune, cure sterility, etc. In one superstition, people who pull up this root will be condemned to hell, and the mandrake root would scream and cry as it was pulled from the ground, killing anyone who heard it.[2] Therefore, in the past, people have tied the roots to the bodies of animals and then used these animals to pull the roots from the soil.[2]

Magic and witchcraft

[edit]

According to the European folklore (including England[53]), when the root is dug up, it screams and kills all who hear it, so that a dog must be attached to the root and made to pull it out. This piece of lore goes back centuries to Josephus's described method of sacrificing the dog to procure his baaras,[54][55] as already described above.

It was a medieval embellishment that the root shrieked when extracted, and so was the lore that mandrake grew from the spots where criminals spilled their fluids. Neither of these were registered by the ancient Greek or Latin authors[e] The mandrake is represented as shining at night like a lantern, in the Old English Herbarium (c. 1000).[56]

In medieval times, mandrake was considered a key ingredient in a multitude of witches' flying ointment recipes as well as a primary component of magical potions and brews.[58] These were entheogenic preparations used in European witchcraft for their mind-altering and hallucinogenic effects.[59] Starting in the Late Middle Ages and thereafter, some believed that witches applied these ointments or ingested these potions to help them fly to gatherings with other witches, meet with the Devil, or to experience bacchanalian carousal.[60][58]

Romani people use mandrake as a love-amulet.[61]

Alraun

[edit]

The German name for mandrake is Alraun, or female case Alraune as already stated, from MHG alrûne,[62] OHG alrûn (alruna.[63][66]).[5] The name has been connected to the female personal name OHG Al(b)rûn, Old English Ælfrūn, Old Norse Alfrún, composed of elements Alb/Alp 'elf, dream demon' + raunen "to whisper"; a more persuasive, though not clinching, explanation is that it derives from *ala- 'all' + *rūnō 'secret' hence "great secret".[5] Grimm explains that it passed from the original meaning of a prophetess type of evil-spirit (or wise woman[67]), into the mandrake or plant-root charm.[68]

The form allerünren (or allerünken[69]) is attested as the Dithmarschen dialect for standard diminutive alrünchen, and in the narrative, the doll is carefully locked in a box, since touching it will impart a power to multiply the dough many times over.[70][71]

The alraune doll was also known by names such as glücksmännchen[72] and galgenmännlein.[72][49] The doll, according to superstition, worked like a charm, bringing its owner luck and fortune.[49]: 319 The glücks-männchen might be a wax doll "ridiculously dressed up".[71] There is also the mönöloke, a wax doll dressed up in the name of the devil,[73] which is considered a parallel or variant of the alrun doll.[69][71]

Because true mandrake does not grow native in Germany, Alrun dolls were being made from cane-roots or false mandrake (German: Gichtrübe;[74] Bryonia alba of the gourd family), recorded in the herbal book by the Italian Pietro Andrea Mattioli (d. 1577/78). The roots are cut approximately to human-like shape, then replanted in the ground for some time. If hair is desired, the root is pockmarked using a sharpened dowel and millet grains pushed into the holes, and replanted until something like a head of hair grows.[75][78][g][h]

The root or rhizome of an iris, gentian or tormentil (Blutwurz) was also purposed for making Alraun dolls. Even the alpine leek (German: Allermannsharnisch; Allium victorialis) was used.[77][49]: 316 The doll formerly owned by Karl Lemann of Wien (cf. fig. right; purchased by Germanisches Nationalmuseum in 1876 where it now remains[81]) had been appraised in the past as having the head made of bryony root, and the body of an alpine leek.[82]

A pair of vintage alraune kept in the Austrian imperial and royal (now national) library, described as being untampered naturally grown roots, belonged to Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II (d. 1612).[83][84]

German sources repeat the recipe of harvesting the mandrake (Alraun) by sacrificing a dog, but demand a "black dog" should be used.[85][88][i] This has passed into German literature,[92][93][95] and into folklore, as compiled by the Brothers Grimm in Deutsche Sagen, No. 83 "Der Alraun".[97] The Grimm version has the black dog tied by the tail,[97] but this is not a constant reflected in all the sources, nor does it match the illustrated depictions show above.

German folklore assigns the alias name Galgenmännlein ("little man of the gallows") to the mandrake, based on the belief the plant springs from the ground beneath a hanged man where his urine or semen had dripped into ground.[9] A more elaborate set of condition had to be met by the hanged man to produce the magic herb in version given by the Grimms' Deutsche Sagen, which essentially amalgamates the formulae from two of its sources.[97]

According to one source, when the hanged man was a hereditary thief (Erbdieb), and the mother while carrying the child either stole or contemplated stealing before giving birth to him, and if died a virgin, then the fluids dripped down will cause a "Galgn-Mänl" to grow there (Grimmelshausen alias Simplicissimus's Galgen-Männlein, 1673).[98] It later states the plant is the product combining the arch-thief's (Erzdieb) soul and his semen or urine.[99][j] The other source states that when an innocent man hanged as a thief releases "water" from the pain and torture he endured, the plant with plantain-like[k] leaves like will grow from that spot. And collecting it requires only that it takes place on a Friday before dawn, with the collector stuffing his ears with cotton and sealing them with wax or pitch, and making the sign of the cross three times while harvesting (Johannes Praetorius, Satrunalia, 1663).[102]

The acquired alraun root needs to be washed with red wine, then wrapped in silk cloth of red and white, and deposited in its own case; it must be removed every Friday and bathed, and new white shirt be given every new moon, according to the Grimms' collated version,[97] but sources will vary on the details.[103]

If questions are posed to the alraun doll, it will reveal the future or secrets, according to superstition. In this way, the owner becomes wealthy. It can also literally double small amounts of money each night by placing a coin on it. It must not be overdone, or the alraun will be tapped of its strength and may die.[97][104] The owner, it is also said, will be able to befriend everybody, and if childless will be blessed with children.[102][105]

When the owner dies, the youngest son will inherit ownership of the doll. In the father's coffin must be placed a piece of bread and a coin. If the youngest son predeceases, then the right of inheritance passes to the eldest son, but the deceased youngest son must also receive his coin and bread in the coffin.[97]

Alraun-drak

[edit]It has been noted that the household kobold may be known regionally as Alraun[e] or Drak, with the same etymological relationship,[106] The drak name does not descend [directly] from Latin draco ("dragon"), but from the mandragora, but folklore about fiery dragons then did get conflated with the notion of the house sprite, according to Heimito von Doderer (cf. also § Nomenclature)[6] Doderer provides commentary that "field dragons" (tatzelwurm) and mandrake fused with the folklore of the house kobold.[6]

Heinrich Marzell's entry in the HdA ventures that the alraun depicted as flying creature laying golden eggs is in fact a dragon,[49]: 47) though the two Swiss examples, the animal is unidentified (Alräunchen, living in the woods at the foot of Hochwang near Chur),[107] or the alrune is a red-crested bird, which others rumored might generate a thaler coin each day for the owner.[108][110]

Main-de-gloire

[edit]In France, there is also the tradition that the man-de-gloire (mandrake) is harvested from under a gibbet.[111]

There is testimony collected firsthand by Sainte-Palaye (d. 1781), in which a peasant claimed to have kept a man-de-gloire found at the base of a mistletoe-bearing oak. The creature was said to be a type of mole. It had to be fed regularly with meat, bread, etc., or suffer dire consequences (two who failed suffered death). But in return, whatever one gave to the man-de-gloire, a double amount or value was restored next day (even an écu of money), thus enriching its keeper.[113][114]

19th century esoterica

[edit]An excerpt from Transcendental Magic: Its Doctrine and Ritual by nineteenth-century clergyman, occultist, and ceremonial magician Éliphas Lévi, suggests the plant might hint at mankind's "terrestrial origin:"

The natural mandragore is a filamentous root which, more or less, presents as a whole either the figure of a man, or that of the virile members. It is slightly narcotic, and an aphrodisiacal virtue was ascribed to it by the ancients, who represented it as being sought by Thessalian sorcerers for the composition of philtres. Is this root the umbilical vestige of our terrestrial origin? We dare not seriously affirm it, but all the same it is certain that man came out of the slime of the earth, and his first appearance must have been in the form of a rough sketch. The analogies of nature make this notion necessarily admissible, at least as a possibility. The first men were, in this case, a family of gigantic, sensitive mandragores, animated by the sun, who rooted themselves up from the earth; this assumption not only does not exclude, but, on the contrary, positively supposes, creative will and the providential co-operation of a first cause, which we have REASON to call GOD. Some alchemists, impressed by this idea, speculated on the culture of the mandragore, and experimented in the artificial reproduction of a soil sufficiently fruitful and a sun sufficiently active to humanise the said root, and thus create men without the concurrence of the female. Others, who regarded humanity as the synthesis of animals, despaired about vitalising the mandragore, but they crossed monstrous pairs and projected human seed into animal earth, only for the production of shameful crimes and barren deformities.[115]

The following is taken from Jean-Baptiste Pitois's The History and Practice of Magic (1870), and explains a ritual for creating a mandrake:

Would you like to make a Mandragora, as powerful as the homunculus (little man in a bottle) so praised by Paracelsus? Then find a root of the plant called bryony. Take it out of the ground on a Monday (the day of the moon), a little time after the vernal equinox. Cut off the ends of the root and bury it at night in some country churchyard in a dead man's grave. For 30 days, water it with cow's milk in which three bats have been drowned. When the 31st day arrives, take out the root in the middle of the night and dry it in an oven heated with branches of verbena; then wrap it up in a piece of a dead man's winding-sheet and carry it with you everywhere.[116]

See also

[edit]- Ginseng – Root of a plant used in herbal preparations (name comes from "human" shape)

- The Spirit in the Bottle – German fairy tale

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ This is a Low German form, but also borrowed in Switzerland, as noted by to Doderer.[6]

- ^ Leyland gives 'little brain thief', which is not wrong, given "brain thief" is a term for mandrake, but pis is literally "piss, urine".

- ^ The Latin text gives "bibitur" rendered "It is drunk.. before incisions and punctures" by Randolph,[22] though the Bostock&Riley translation phrases it as "It is given".

- ^ Sir Thomas Browne, in Pseudodoxia Epidemica, however, suggests the dudaʾim of Genesis 30:14 refers only to the opium poppy (as a metaphor describing a woman's breasts.).

- ^ Pliny (or Josephus), and Theophrastus.[55]

- ^ Workshop of N. Italy (Verona, Italy). While this late 14th century copy features a black and white dog, a white dog is shown in the mid-15th century BnF (Paris) copy (ms. Latin 9333, fol. 37r) made in Rhineland, Germany presumably from an Italian original.[57]

- ^ Gichtrube[74] answers to Bryonia alba, and while the latter quote from Mattioli stating "Brionienwurtz"[76] may seem ambiguous as to species, Mattioli elsewhere describes the type that grows in Hungary and Germany to be black-berried (not red),[79] which is sufficient as identifier.

- ^ Praetorius in his Anthropodemus: Neue Welt-Beschreibung, Volume 2 gives a different German name,schwarz Stickwurgel.[80] Mattioli lists the German names Stickwurtz, Teufelskürbtz (latter prob. "devil gourd") in his Latin treatise entry for this plant.[79] The present-day common name in German seems to be Weiße Zaunrübe.

- ^ Either black or a black and white dog, according to some sources[89][90] (cf. illustration in the Wien copy of Tacuinum Sanitatis, below).

- ^ The Grimms cite Simplicissimus Galgen-Männlein. It is generally known Simplicissimus was a pseudo-author/character invented by Grimmelshausen. The work's title also mentions as informant or co-author an "Israel Fromschmidt [von Hugenfelss]" (Grimms' Fron- is a typo), but this personage is also an anagram pseudonym of Grimmelshausen.[100] The date of authorship was solved from a chronogram as 1673.[101]

- ^ German: Wegerich.

References

[edit]- ^ Wolfthal (2016) Fig. 8-10

- ^ a b c John Gerard (1597). "Herball, Generall Historie of Plants". Claude Moore Health Sciences Library. Archived from the original on 2012-09-01. Retrieved 2015-08-03.

- ^ Greenough, James Bradstreet (1901). Words and Their Ways in English Speech. New York: Macmillan. pp. 340–341.

- ^ Wedgwood, Hensleigh (1855). "On False Etymologies". Transactions of the Philological Society (6): 67.: babel

.hathitrust @ HathiTrust (US only).org /cgi /pt?id=uc1 .b3924121%3Bview%3D1up%3Bseq%3D79%3D+2%3De-text - ^ a b c Kluge, Friedrich; Seebold, Elmar, eds. (2012) [1899]. "Alraun". Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache (25 ed.). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 35. ISBN 9783110223651.; cf. 6th edition, Band. 1 (1899)

- ^ a b c d Doderer, Heimito von (1996) [1959]. Schmidt-Dengler, Wendelin [in German] (ed.). Die Wiederkehr der Drachen. C.H.Beck. p. 33. ISBN 978-3-406-40408-5.; repr. of: Doderer, Heimito von (1959). "Die Wiederkehr der Drachen". Atlantis: Länder, Völker, Reisen. 31: 112.

- ^ a b Weiser-Aall, Lily (1933) "Kobold", HdA, 5:29–47

- ^ Harris (1917), p. 370.

- ^ a b c Simoons (1998), pp. 121–122.

- ^ Grimm, Jacob (1883). "XVII. Wights and Elves §Elves, Dwarves". Teutonic Mythology. Vol. 2. Translated by James Steven Stallybrass. W. Swan Sonnenschein & Allen. p. 513, n1.; German: Grimm, Jacob (1875). "(Anmerkung von) XXXVII. Kräuter und Steine". Deutsche Mythologie. Vol. 3 (2 ed.). Göttingen: W. Swan Sonnenschein & Allen. pp. 352–353., note to text in Grimm (1877) 2: 1007.

- ^ a b De Cleene, Marcel; Lejeune, Marie Claire, eds. (2002). Compendium of Symbolic and Ritual Plants in Europe: Herbs. Vol. 2. Ghent: Man & Culture. p. 336. ISBN 9789077135044.

- ^ Leland, Charles Godfrey (1892). Etruscan Roman Remains in Popular Tradition. T. F. Unwin.

- ^ Jiménez-Mejías, M.E.; Montaño-Díaz, M.; López Pardo, F.; Campos Jiménez, E.; Martín Cordero, M.C.; Ayuso González, M.J. & González de la Puente, M.A. (1990-11-24). "Intoxicación atropínica por Mandragora autumnalis: descripción de quince casos [Atropine poisoning by Mandragora autumnalis: a report of 15 cases]". Medicina Clínica. 95 (18): 689–692. PMID 2087109.

- ^ Piccillo, Giovita A.; Mondati, Enrico G. M. & Moro, Paola A. (2002). "Six clinical cases of Mandragora autumnalis poisoning: diagnosis and treatment". European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 9 (4): 342–347. doi:10.1097/00063110-200212000-00010. PMID 12501035.

- ^ a b c d A Modern Herbal, first published in 1931, by Mrs. M. Grieve, contains Medicinal, Culinary, Cosmetic and Economic Properties, Cultivation and Folk-Lore.

- ^ a b Randolph (1905), p. 358.

- ^ Theophrastus (1016). "IX.8.7". Enquiry Into Plants. The Loeb Classical Library. Vol. 2. Translated by Arthur Hort. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 258–259.

- ^ Preus, Anthony (1988). "6. Drugs and Pyschic States in Theophrastus' Historia plantarum". In Fortenbaugh, William Wall; Sharples, Robert W. (eds.). Renaissance Posthumanism. Rutgers Univ. studies in classical humanities 3. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. p. 79. ISBN 9781412839730.

- ^ Theophrastus HN 9.8.8,"περιγράφειν δὲ καὶ τὸν μανδραγόραν εἰς τρὶς ξίφει..τὸν δ᾽ ἕτερον κύκλῳ περιορχεῖσθαι καὶ λέγειν ὡς πλεῖστα περὶ ἀφροδισίων.",[16] Hort renders it as "one should dance round the plant and say as many things as possible about the mysteries of love",[17] whereas Preus gives it directly as "say as much as possible about sexual intercourse".[18]

- ^ a b c d Wolfthal, Diane (2016). "8. Beyond Human: Visualizaing the Sexuality of Abraham Bosse's Mandrake". In Campana, Joseph; Maisano, Scott (eds.). Renaissance Posthumanism. Fordham Univ Press. ISBN 9780823269570.

- ^ a b Taylor, Joan E. (2012). The Essenes, the Scrolls, and the Dead Sea. OUP Oxford. pp. 317–318. ISBN 9780191611902.

- ^ a b c Randolph (1905), p. 514.

- ^ Finger, Stanley (2001). Origins of Neuroscience: A History of Explorations Into Brain Function. Oxford University Press. p. 159. ISBN 9780195146943.

- ^ Disoscrides 1.571 gives "Some persons boil down the roots in wine to a third, strain it.. using one cyathus.. to [insominiacs or] persons about to be cut or cauterized".[22] Though cast in third person, possibly "Dioscorides administered", himself, according to Finger.[23]

- ^ a b c Plinius Liber XXV. XCIII.[27][28]

- ^ Randolph (1905), p. 507.

- ^ Plinius. "Liber XXV.XCIII". – via Wikisource.

- ^ Pliny the Elder (1856). "Book XXV, Chap. 94. Mandragora, Circæon, Morion, or Hippophlomos; Two varieties of it; Twenty-Four Remedies". The Natural History of Pliny. Vol. 5. Translated by Bostock, John Bostock; Riley, Henry Thomas. London: Henry G. Bohn. pp. 138–140.

- ^ a b c Plinius Liber XXV. XCIII.[30][31]

- ^ Plinius. "Liber XXII.IX". – via Wikisource.

- ^ Pliny the Elder (1856). "Book XXII, Chap. 94. Mandragora, Circæon, Morion, or Hippophlomos; Two varieties of it; Twenty-Four Remedies". The Natural History of Pliny. Vol. 4. Translated by Bostock, John Bostock; Riley, Henry Thomas. London: Henry G. Bohn. pp. 138–140.

- ^ Harris (1917), pp. 356–357.

- ^ Carod-Artal, F. J. (2013). "Psychoactive plants in ancient Greece". nah.sen.es. Archived from the original on 2022-03-28. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- ^ a b c d Post, George E. (October 2004). "mandrake". In Hastings, James (ed.). A Dictionary of the Bible: Volume III: (Part I: Kir -- Nympha). University Press of the Pacific. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-4102-1726-4. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ a b Randolph (1905), pp. 503–504.

- ^ Hastings, "love philtre", citing Genesis 3:14–18[34]

- ^ a b Matskevich, Karalina (2019). "3. The Mothers in the Jacob Narrative (Gen. 25.19-37.1) § The dûdāʾim of Reuben". Construction of Gender and Identity in Genesis: The Subject and the Other. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 185. ISBN 9780567673770.

- ^ "Genesis 30:14–16 (King James Version)". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^

And Reuben went in the days of wheat harvest, and found mandrakes in the field, and brought them unto his mother Leah. Then Rachel said to Leah, Give me, I pray thee, of thy son's mandrakes. And she said unto her, Is it a small matter that thou hast taken my husband? and wouldest thou take away my son's mandrakes also? And Rachel said, Therefore he shall lie with thee to night for thy son's mandrakes. And Jacob came out of the field in the evening, and Leah went out to meet him, and said, Thou must come in unto me; for surely I have hired thee with my son's mandrakes. And he lay with her that night.

— the Bible, King James Version, Genesis 30:14–16[38]

- ^ Genesis 30:14–22

- ^ Levenson, Alan T. (2019). "1. Joseph. Favored Son, Hated Brother". Joseph: Portraits Through the Ages. U of Nebraska Press, 2016. p. 1. ISBN 9780827612945.

- ^ "Song of Songs 7:12–13 (King James Version)". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ a b Druce (1919), p. 62, and p. 58 (Plate VIII)

- ^ Simoons (1998), pp. 109–110.

- ^ Randolph (1905), pp. 502–503.

- ^ Philippe de Thaun (1841). "The Bestiary of Philipee de Thaun". In Wright, Thomas (ed.). Popular Treatises on Science Written During the Middle Ages: In Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Norman and English. London: Historical Society of Science. p. 101-102.. For example, "Cocodrille, p. 85" corresponds to folio 50r of Cotton MS Nero A V digitized @ British Library.

- ^ Simoons (1998), p. 380 (n189 to pages 124–125)

- ^ a b c Josephus (1835). "The Jewish War VII.VI.3". The Works of Flavius Josephus: The Learned and Authentic Jewish Historian and Celebrated Warrior. With Three Dissertations, Concerning Jesus Christ, John the Baptist, James the Just, God's Command to Abraham, &c. and Explanatory Notes and Observation. Translated by William Whiston. Baltimore: Armstrong and Plaskitt, and Plaskitt & Company. p. 569.

- ^ a b c d e Marzell, Heinrich [in German] (1987) [1927]. "Kobold". In Bächtold-Stäubli, Hanns [in German]; Hoffmann-Krayer, Eduard (eds.). Handwörterbuch des Deutschen Aberglaubens. Vol. Band 1 Aal-Butzemann. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 312–324. ISBN 3-11-011194-2.

- ^ Macherus,[48] Machärus[49]: 11)

- ^ Ginzberg, Louis (1925). The Legends of the Jews: Notes to volumes 1 and 2: From the creation to the exodus. Translated by Henrietta Szold; Paul Radin. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America. p. 298.

- ^ Lippmann, Edmund Oskar von (1894). Über einen naturwissenschaftlichen Aberglauben: nach einem Vortrage gehalten in der Naturforschenden. Halle a. Saale: M. Niemeyer. p. 4.

- ^ Harris (1917), p. 356.

- ^ Harris (1917), p. 365.

- ^ a b Simoons (1998), pp. 121–124.

- ^ Hatsis, Thomas (2015). "4. Roots of Bewitchment". The Witches' Ointment: The Secret History of Psychedelic Magic. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781620554746.

- ^ Kyle, Sarah R. (2023). "Chapter 8. The Representation of Plants: Mediators of Body and Soul". In Touwaide, Alain (ed.). A Cultural History of Plants in the Post-Classical Era. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 184–185, Fig. 8.7. ISBN 9781350259294.

- ^ a b Hansen, Harold A. The Witch's Garden pub. Unity Press 1978 ISBN 978-0-913300-47-3

- ^ Rätsch, Christian (2005). The encyclopedia of psychoactive plants: ethnopharmacology and its applications. Rochester, Vermont: Park Street Press. pp. 277–282.

- ^ Peters, Edward (2001). "Sorcerer and Witch". In Jolly, Karen Louise; Raudvere, Catharina; et al. (eds.). Witchcraft and Magic in Europe: The Middle Ages. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 233–37. ISBN 978-0-485-89003-7.

- ^ Gerina Dunwich (September 2019). Herbal Magick: A Guide to Herbal Enchantments, Folklore, and Divination. Weiser Books. ISBN 978-1-63341-158-6.

- ^ Lexer (1878). "al-rûne", Mittelhochdeutsches Handwörterbuch

- ^ Steinmeyer & Sievers (1895) AHD Gl. 3 alrûna, alruna p. 100; alrun p. 326; alrune, p. 536

- ^ R (1839). "VIII. Teutsche Glossare und Glossen. 61. Glossaria Augiensia". In Mone, Franz Joseph [in German] (ed.). Anzeiger für Kunde des deutschen Mittelalters. Vol. 8. Kralsruhe: Christian Theodor Groos. p. 397.

- ^ Grimm, Jacob (1888). "(Notes to) XVII. Wights and Elves §Elves, Dwarves". Teutonic Mythology. Vol. 4. Translated by James Steven Stallybrass. W. Swan Sonnenschein & Allen. p. 1399, note to Vol. 2:405.; German: Grimm, Jacob (1878). "(Anmerkung zu) XVI. Weise Frauen". Deutsche Mythologie. Vol. 3 (4 ed.). Göttingen: W. Swan Sonnenschein & Allen. p. 115, Anmerk. zu Band 1: S. 334, 335.

- ^ The form alruna is also attested in the Glossaria Augiensia of Reichenau Abbey, 13th cent., ed. Mone,[64] cited by Grimm DM, Anmerkungen.[65]

- ^ a b Grimm, Jacob (1883b). "XXXVII. Herbs and Stones §Mandrake, Alraun". Teutonic Mythology. Vol. 3. Translated by James Steven Stallybrass. W. Swan Sonnenschein & Allen. pp. 1202–1203.; German: Grimm, Jacob (1876). "XXXVII. Kräuter §Alraun". Deutsche Mythologie. Vol. 2 (4 ed.). Berlin: Ferd. Dummlers Verlagsbuchhandlung. pp. 1005–1007.

- ^ Grimm, Jacob (1880). "XVI. Wise Women §Alarûn". Teutonic Mythology. Vol. 1. Translated by James Steven Stallybrass. W. Swan Sonnenschein & Allen. pp. 404–405.; German: Grimm, Jacob (1875). "XVI. Weise Frauen". Deutsche Mythologie. Vol. 1 (4 ed.). Göttingen: W. Swan Sonnenschein & Allen. pp. 334–335.

- ^ a b Bechstein, Ludwig (1853). "182. Allerünken". Deutsches Sagenbuch. Illustrated by Adolf Ehrhardt. Leipzig: Georg Wigand. pp. 167–168.

- ^ Müllenhoff (1845). "CCLXXXV. Das Allerürken", pp. 209–210.

- ^ a b c Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1888) Vol. 4: 1435, note to Vol. 2: p. 513n: "The allerürken [sic].."; German: Grimm (1878). Band 3: 148, Anmerkung zu Band 1, S. 424.

- ^ a b Ersch, Johann Samuel; Gruber, Johann Gottfried, eds. (1860). "Glücksmännchen". Allgemeine Encyclopädie der Wissenschaften und Künste. Vol. 1. Leipzig: Brockhaus. pp. 303–304.

- ^ Müllenhoff (1845). "CCLXXXIV. Mönöloke", p. 209.

- ^ a b Praetorius (1663), p. 158.

- ^ Mattioli's herbal tome, Book 4, Chapter 21, cited by Praetorius (1663), p. 158

- ^ a b Mattioli, Pietro Andrea (1563). "Vom Alraun Cap. LXXV.". New Kreüterbuch: Mit den allerschönsten vnd artlichsten Figuren aller Gewechß, dergleichen vormals in keiner sprach nie an tag kommen. Prague: Melantrich von Auentin und Valgriß. pp. 467–468.

- ^ a b c d e Marzell, Heinrich [in German] (1922). "6. Kapitel. Heren- und Zauberpflanzen". Die heimische Pflanzenwelt im Volksbrauch und Volksglauben: Skizzen zur deutschen Volkskunde. Leipzig: Quelle & Meyer. pp. 95–96.

- ^ Mattioli (1563), Das Vierdte Buch von der Kreuter, "Vom Alraun Cap. LXXV",[76] requoted by Marzell.[77]

- ^ a b Mattioli, Pietro Andrea (1586). "Vitis alba, siue Bryonia". De Plantis epitome vtilissima, Petri Andreae Matthioli Senensis... novis plane, et ad vivum expressis iconibus, descriptionibusque... nunc primum diligenter aucta, et locupletata, à D. Ioachimo Camerario... Accessit... liber singularis de itinere ab urbe Verona in Baldum montem plantarum ... Frankfurt am Main: Johann Feyerabend. p. 987.

- ^ a b Praetorius, Johannes (1677). "VIII. Von Holz-Menschen". Ander Theil der Neuen Welt-Beschreibung. Vol. 2. Magdeburg: In Verlegung Johann Lüderwalds. pp. 215, 216!--215–233-->.

- ^ Germanisches Nationalmuseum. "Alraunmännchen". Ihr Museum in Nürnberg. Retrieved 2024-10-01.

- ^ Perger, Anton Franz Ritter von [in German] (May 1861). Über den Alraun. Schriften des Wiener-Alterthumsvereins. p. 268, Fig. C. alt etext @ books.google

- ^ Perger (1861), pp. 266–268, Fig. A and B.

- ^ Wolfthal (2016) Fig. 8-8

- ^ Mattioli, op. cit.[77]

- ^ Libavius, Andreas (1599). Singularium Andreae Libavii Pars Secunda... Francofurti: Kopffius. p. 313.

- ^ Schlosser (1912), p. 28.

- ^ Andreas Libavius Singularium Pars II (1599), under "Exercitatio de agno vegetabili Scythiae" (Vegetable Lamb of Tartary)、p, 313.[86][87]

- ^ Couper, John L. (1988). "The Mandrake Legend". Adler Museum Bulletin. 14 (2): 21. hdl:11149/1627.

- ^ Rieder, Marilise; Rieder, Hans Peter; Suter, Rudolf, eds. (2013). "Zauberpflanzen". Basilea botanica. Springer-Verlag. p. 233. ISBN 9783034865708.

- ^ Grimmelshausen (1673), pp. 7–8.

- ^ Grimmelshausen (1673), Galgen-Männlein, p. 4 notes that Alraun requires a black dog, just like Josephus prescribes for extracting Baraas [sic], then elaborates on Josephus's method in the Annotatio.[91]

- ^ Praetorius (1663) Saturnalia ("Saturnalia: That Is, A Company of Christmastide Antics"), pp. 166–167 also cite Josephus, The Jewish War Book 7, Ch. 25 and explain the procedure for unrooting the Baaras (correct spelling).

- ^ Praetorius, Johannes (1666). "XV. Von Pflantz-Leuten". Anthropodemus Plutonicus. Das ist, Eine Neue Welt-beschreibung Von allerley Wunderbahren Menschen. Vol. 1. Illustrated by Thomas Cross (fl. 1632-1682). Magdeburg: In Verlegung Johann Lüderwalds. pp. 172, 184.

- ^ Praetorius's Anthropodemus: Neue Welt-beschreibung volume 1, ch. 5 on "Plant-people" discusses the alraun and black dog,[94] but Grimm's citation only includes volume 2, ch. 8 on the "Wood-man", with some bits of information.[80]

- ^ Grimms, ed. (1816). "83. Der Alraun". Deutsche Sagen. Vol. 1. Berlin: Nicolai. pp. 135–137.

- ^ a b c d e f Grimms' DS No. 83,[96] redacted in Grimm DM 4te Ausgabe, Band II, Kap. XXXVII[67]

- ^ Grimmelshausen (1673), pp. 3–4.

- ^ Grimmelshausen (1673), pp. 22–23.

- ^ Breuer, Dieter (2005). Simpliciana: Schriften der Grimmelshausen-Gesellschaft XXVI (2004). in Verbindung Mit Dem Vorstand der Grimmelshausen-Gesellschaft. Peter Lang. p. 64. ISBN 9783039106264.

- ^ Scholte, Jan Hendrik (1921). Zonagri Discurs von Waarsagern: Ein Beitrag zu unserer Kenntnis von Grimmelshausens Arbeitsweise in seinem Evigwährenden Calendar mit besonderer Berücksichtiging des Eingangs des abentheuerlichen Simplicissimus. Amesterdam: Johannes Müller. p. 79.

- ^ a b c Praetorius, Johannes (1663). "Propositio VII". Saturnalia, das ist eine Compagnie Weihnachts-Fratzen oder Centner-Lügen [Saturnalia: That Is, A Company of Christmastide Antics]. Leipzig: Joh. Wittigau. pp. 155, 156 !--155–190-->. ((Also figures A, B of male and female mandrakes, Imperial Library, Vienna, pp. 183, 189)

- ^ Mattioli: washed with wine and water all Saturday long;[77] Grimmelshausen (1673), p. 4: wash with red wine, wrap in soft linen or silk, and bathe every Friday. Praetorius Saturnalia: wrap in white and red silk, encased, and prayed to.[102]

- ^ Grimm, after Grimmelshausen (1673), p. 3 provides the monetary limits. A ducat (gold coin) will rarely succeed in doubling, and if the owner wants the doll to endure, a half thaler (silver coin) would be about the limit.

- ^ Mattioli also remarks that the barren will become fertile.[77]

- ^ Classification "I Drachennamen".[7]

- ^ Vernaleken, Theodor [in German], ed. (1859). "60. [Alräunchen] (informant: Chr. Tester in Chur)". Mythen und bräuche des volkes in Oesterreich: als beitrag zur deutschen mythologie, volksdichtung und sittenkunde. Wien: W. Braumüller. p. 260.

- ^ Rochholz, Ernst Ludwig [in German] (1856). "268. Die Alrune zu Buckten". Schweizersagen aus dem Aargau: Gesammelt und erlauetert. Vol. 2. Aarau: H.R. Sauerlaender. p. 43.

- ^ Polívka, Georg (1928). "Die Entstehung eines dienstbaren Kobolds aus einme Ei". Zeitschrift für Volkskunde. 18. Johannes Bolte: 41–56.

- ^ Note that Polívka in his paper on the lore of kobolds born from an egg (much of it from Pommerania, now straddling Germany and Poland) makes connection to Wendian lore about a black hen hatching dragon (p. 55) similar to the well-known lore on the basilisk (passim), also noting that the Alraunmanchenn is the agent performing the luck- or gold-bringing task for the owner.[109]

- ^ Harris (1917), p. 372.

- ^ Harris (1917), pp. 372–373.

- ^ The ultimate source (which work or document by Palaye) is not clarified, and Rendel Harris quotes Palaye in French out of Pierre Adolphe Chéruel (1855) Dictionnaire historique.[112]

- ^ Folkard, Richard (1884). Plant Lore, Legends, and Lyrics: Embracing the Myths, Traditions, Superstitions, and Folk-lore of the Plant Kingdom. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington. p. 428.

- ^ pp. 312, by Eliphas Levi. 1896

- ^ pp. 402-403, by Paul Christian. 1963

Bibliography

[edit]- Druce, George C (1919). "The Mediæval Bestiaries, and Their Influence on Ecclesiastical Decorative Art". Journal of the British Archaeological Association. 25 (1): 41–82. doi:10.1080/00681288.1919.11894541.

- Grimmelshausen, Jacob Christoffel von (pseudonyms: Simplicissmus, Israël Fromschmidt von Hugenfeltß) (1673). Simplicissimi Galgen-Männlin.

- Harris, J. Rendel (1917). Guppy, Henry (Librarian of John Rylands Library) (ed.). "The Origin of the Cult of Aphrodite". Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 3 (4). Manchester University Press: 354–381. doi:10.7227/BJRL.3.4.2.

- Müllenhoff, Karl, ed. (1845). Sagen, Märchen und Lieder der Herzogthümer Schleswig Holstein und Lauenburg. Schwerssche Buchhandlung.

- ——(1899). Reprint. Siegen: Westdeutschen Verlagsanstalt

- Randolph, Charles Brewster (1905). "Mandragora in Folk-lore and Medicine". Daedalus: Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 40. MIT Press: 87–587.

- Schlosser, Alfred (1912). Die Sage vom Galgenmännlein im Volksglauben und in der Literatur (Ph. D.). Münster in Westfalen: Druck der Theissingschen buchhandlung.

- Simoons, Frederick J. (1998). "Chapter 4. Mandrake, a Root Human in Form". Plants of Life, Plants of Death, Frederick J. Simoons. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 101–135. ISBN 9780299159047.

- Steinmeyer, Elias; Sievers, Eduard, eds. (1895). Die althochdeutschen Glossen. Vol. 3. Berlin: Weidmann.

Further reading

[edit]- Heiser, Charles B. Jr (1969). Nightshades, The Paradoxical Plant, 131-136. W. H. Freeman & Co. SBN 7167 0672-5.

- Thompson, C. J. S. (reprint 1968). The Mystic Mandrake. University Books.

- Muraresku, Brian C. (2020). The Immortality Key: The Secret History of the Religion with No Name. Macmillan USA. ISBN 978-1-250-20714-2

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.