Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Eight-thousander

View on Wikipedia

The eight-thousanders are 14 mountains recognized by the International Mountaineering and Climbing Federation (UIAA) with summits that exceed 8,000 metres (26,247 ft) in elevation above sea level and are sufficiently independent of neighbouring peaks as measured by topographic prominence. There is no formally agreed-upon definition of prominence, however, and at times the UIAA has considered whether the list of 8,000-metre peaks should be expanded to 20 peaks by including the major satellite peaks of the canonical 14 eight-thousanders. All of the Earth's eight-thousanders are located in the Himalayan and Karakoram mountain ranges in Asia, and their summits lie in the altitude range known as the death zone, where atmospheric oxygen pressure is insufficient to sustain human life for extended periods of time.

From 1950 to 1964, all 14 of the eight-thousanders were first summited by expedition climbers in the summer season (the first to be summited was Annapurna I in 1950, and the last was Shishapangma in 1964); from 1980 to 2021, all 14 were summited in the winter season (the first to be summited in winter was Mount Everest in 1980, and the last was K2 in 2021). As measured by a variety of statistical techniques, the deadliest eight-thousander is Annapurna I, with one death (climber or climber support) for every three summiters, followed by K2 and Nanga Parbat (each with one death for every four to five summiters), and then Dhaulagiri and Kangchenjunga (each with one death for every six to seven summiters).

The first person to summit all 14 eight-thousanders was the Italian climber Reinhold Messner in 1986, who did not use any supplementary oxygen. In 2010, Edurne Pasaban, a Basque Spanish mountaineer, became the first woman to summit all 14 eight-thousanders, but with the aid of supplementary oxygen. In 2011, Austrian Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner became the first woman to summit all 14 eight-thousanders without the aid of supplementary oxygen. In 2013, South Korean Kim Chang-ho set a speed record by climbing all 14 eight-thousanders in 7 years and 310 days, without the aid of supplementary oxygen. In July 2023, Kristin Harila and Tenjen Lama Sherpa set a speed record of 92 days for climbing all 14 eight-thousanders, with supplementary oxygen. In July 2022, Sanu Sherpa became the first person to summit all 14 eight-thousanders twice, which he did from 2006 to 2022.

Issues with false summits (e.g. Cho Oyu, Annapurna I, and Dhaulagiri), or separated dual summits (e.g. Shishapangma and Manaslu), have led to disputed claims of ascents.[1] In 2022, after several years of research, a team of experts reported that they could only confirm evidence that three climbers (Ed Viesturs, Veikka Gustafsson and Nirmal Purja) had stood on the true geographic summit of all 14 eight-thousanders.[2]

Climbing history

[edit]First ascents

[edit]

The first recorded attempt on an eight-thousander was when Albert F. Mummery, Geoffrey Hastings and J. Norman Collie tried to climb Nanga Parbat in 1895. The attempt failed when Mummery and two Gurkhas, Ragobir Thapa and Goman Singh, died in an avalanche.[3]

The first successful ascent of an eight-thousander was by the French climbers Maurice Herzog and Louis Lachenal, who reached the summit of Annapurna on 3 June 1950 using expedition climbing techniques as part of the 1950 French Annapurna expedition.[4] Due to its location in Tibet, Shishapangma was the last eight-thousander to be ascended for the first time, which was completed by a Chinese team led by Xu Jing in 1964 (Tibet's mountains were closed by China to foreigners until 1978).[5]

The first winter ascent of an eight-thousander was by a Polish team led by Andrzej Zawada on Mount Everest, with Leszek Cichy and Krzysztof Wielicki reaching the summit on 17 February 1980;[6] all-Polish teams would complete nine of the first fourteen winter ascents of eight-thousanders.[7] The final eight-thousander to be climbed in winter was K2, whose summit was ascended by a 10-person Nepalese team on 16 January 2021.[8]

Only two climbers have completed the first ascent of more than one eight-thousander, Hermann Buhl (Nanga Parbat and Broad Peak, in 1953 and 1957) and Kurt Diemberger (Broad Peak and Dhaulagiri, in 1957 and 1960). Buhl's summit of Nanga Parbat in 1953 is notable as being the only solo first-ascent of an eight-thousander.[9] The Polish climber Jerzy Kukuczka is noted for creating over ten new routes on various eight-thousander mountains.[7] Italian climber Simone Moro made the first winter ascent of four eight-thousanders (Shishapangma, Makalu, Gasherbrum II, and Nanga Parbat),[10] while three Polish climbers have each made three first winter ascents of an eight-thousander, Maciej Berbeka (Cho Oyu, Manaslu, and Broad Peak), Krzysztof Wielicki (Everest, Kangchenjunga, and Lhotse) and Jerzy Kukuczka (Dhaulagiri I, Kangchenjunga, and Annapurna I).[7]

All 14

[edit]

On 16 October 1986, Italian Reinhold Messner became the first person to climb all 14 eight-thousanders. In 1987, Polish climber Jerzy Kukuczka became the second person to accomplish this feat.[7] Messner summited each of the 14 peaks without the aid of bottled oxygen, a feat that was only repeated by the Swiss Erhard Loretan nine years later in 1995 (Kukuczka had used supplementary oxygen while summiting Everest but on no other eight-thousander[7]).[12]

On 17 May 2010, Spanish climber Edurne Pasaban became the first woman to summit all 14 eight-thousanders.[13] In August 2011, Austrian climber Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner became the first woman to climb the 14 eight-thousanders without the use of supplementary oxygen.[14][15]

The first couple and team to summit all 14 eight-thousanders were the Italians Nives Meroi (who was the second woman to accomplish this feat without supplementary oxygen), and her husband Romano Benet on 11 May 2017.[16][17] The couple climbed alpine style, without the use of supplementary oxygen or other support.[17][18]

On 22 May 2024, Nepali guide Kami Rita summitted Everest for the 30th time (a record for Everest), also becoming the first-ever person to climb an eight-thousander 41 times.[19] In July 2022, Sanu Sherpa became the first person to summit all 14 eight-thousanders twice.[20] He started with Cho Oyu in 2006, and completed the double by summiting Gasherbrum II in July 2022.[21]

On 20 May 2013, South Korean climber Kim Chang-ho set a new speed record of climbing all 14 eight-thousanders, without the use of supplementary oxygen, in 7 years and 310 days. On 29 October 2019, the British-Nepali climber Nirmal Purja set a speed record of 6 months and 6 days for climbing all 14 eight-thousanders with the use of supplementary oxygen.[22][23][24] On 27 July 2023, Kristin Harila and Tenjen Lama Sherpa set a new speed record of 92 days for climbing all 14 eight-thousanders with supplementary oxygen.[25][26]

Deadliest

[edit]| Eight thousander |

From 1950 to March 2012[29] | Climber death rate [30][31][a] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total ascents[b] |

Total deaths[c] |

Deaths as % of ascents[d] | ||

| Everest | 5656 | 223 | 3.9% | 1.52% |

| K2 | 800 | 96 | 12% | |

| Lhotse | 461 | 13 | 2.8% | 1.03% |

| Makalu | 361 | 31 | 8.6% | 1.63% |

| Cho Oyu | 3138 | 44 | 1.4% | 0.64% |

| Dhaulagiri I | 448 | 69 | 15.4% | 2.94% |

| Manaslu | 661 | 65 | 9.8% | 2.77% |

| Nanga Parbat | 335 | 68 | 20.3% | –[e] |

| Annapurna I | 191 | 61 | 31.9% | 4.05% |

| Gasherbrum I (Hidden Peak) |

334 | 29 | 8.7% | –[e] |

| Broad Peak | 404 | 21 | 5.2% | –[e] |

| Gasherbrum II | 930 | 21 | 2.3% | –[e] |

| Kangchenjunga | 243 | 40 | 16% | 3.00% |

| Shishapangma | 302 | 25 | 8.3% | |

The eight-thousanders are the world's deadliest mountains. The extreme altitude and the fact that the summits of all eight-thousanders lie in the Death Zone mean that climber mortality (or death rate) is high.[33] Two metrics are quoted to establish a death rate (i.e. broad and narrow) that are used to rank the eight-thousanders in order of deadliest.[32][34]

- Broad death rate: The first metric is the ratio of total deaths[c] on the mountain to successful climbers summiting over a given period.[32] The Guinness Book of World Records uses this metric to name Annapurna I as the deadliest eight-thousander, and the world's deadliest mountain with roughly one person dying for every three people who successfully summit, i.e. a ratio of circa 30%.[35] Using consistent data from 1950 to 2012, mountaineering statistician Eberhard Jurgalski (see table) used this metric to show Annapurna is the deadliest mountain (31.9%), followed by K2 (26.5%), Nanga Parbat (20.3%), Dhaulagiri (15.4%) and Kangchenjunga (14.1%).[32] Other statistical sources including MountainIQ, used a mix of data periods from 1900 to Spring 2021 but had similar results showing Annapurna still being the deadliest mountain (27.2%), followed by K2 (22.8%), Nanga Parbat (20.75%), Kangchenjunga (15%), and Dhaulagiri (13.5%).[34][33] Cho Oyu was the safest at 1.4%.[32][34]

- Narrow death rate: The drawback of the first metric is that it includes the deaths of any support climbers or climbing sherpas that went above base camp in assisting the climb; therefore, rather than being the probability that a climber will die attempting to summit an eight-thousander, it is more akin to the total human cost in getting a climber to the summit.[30] In the Himalayan Database (HDB) tables, the climber (or member) "Death Rate" is the ratio of deaths above base camp, of all climbers who were hoping to summit and who went above base camp (calculated for 1950 to 2009), and is closer to a true probability of death (see table below).[30] The data is only for the Nepalese Himalaya and therefore does not include K2 or Nanga Parbat.[30] HDB estimates the probability of death for a climber attempting the summit of an eight-thousander is still highest for Annapurna I (4%), followed by Kangchenjunga (3%) and Dhaulagiri (3%); the safest is still Cho Oyu at 0.6%.[30]

The tables from the HDB for eight-thousanders also show that the death rate of climbers for the period 1990 to 2009 (e.g. modern expeditions), is roughly half that of the combined 1950 to 2009 period, i.e. climbing is becoming safer for the climbers attempting the summit.[30]

List of first ascents

[edit]From 1950 to 1964, all 14 of the eight-thousanders were summited in the summer (the first was Annapurna I in 1950, and the last was Shishapangma in 1964), and from 1980 to 2021, all 14 were summited in the winter (the first being Everest in 1980, and the last being K2 in 2021).

| Mountain[27] | First ascent[27] | First winter ascent[27] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Height[36] | Prom.[36] | Country | Date | Summiter(s) | Date | Summiter(s) |

| Everest | 8,849 m (29,032 ft)[37] |

8,849 m (29,032 ft) |

29 May 1953[f] |

17 February 1980 |

|||

| K2 | 8,611 m (28,251 ft) |

4,020 m (13,190 ft) |

31 July 1954 | 16 January 2021[8] |

| ||

| Kangchenjunga | 8,586 m (28,169 ft) |

3,922 m (12,867 ft) |

25 May 1955 | on British expedition |

11 January 1986 | ||

| Lhotse | 8,516 m (27,940 ft) |

610 m (2,000 ft) |

18 May 1956 | 31 December 1988 | |||

| Makalu | 8,485 m (27,838 ft) |

2,378 m (7,802 ft) |

15 May 1955 | on French expedition |

9 February 2009 | ||

| Cho Oyu | 8,188 m (26,864 ft) |

2,344 m (7,690 ft) |

19 October 1954 | 12 February 1985 | |||

| Dhaulagiri I | 8,167 m (26,795 ft) |

3,357 m (11,014 ft) |

13 May 1960 | 21 January 1985 | |||

| Manaslu | 8,163 m (26,781 ft) |

3,092 m (10,144 ft) |

9 May 1956 | 12 January 1984 | |||

| Nanga Parbat | 8,125 m (26,657 ft) |

4,608 m (15,118 ft) |

3 July 1953 | on German–Austrian expedition |

26 February 2016 | ||

| Annapurna I | 8,091 m (26,545 ft) |

2,984 m (9,790 ft) |

3 June 1950 | 3 February 1987 | |||

| Gasherbrum I (Hidden Peak) |

8,080 m (26,510 ft) |

2,155 m (7,070 ft) |

5 July 1958 | 9 March 2012 | |||

| Broad Peak | 8,051 m (26,414 ft) |

1,701 m (5,581 ft) |

9 June 1957 | 5 March 2013 | |||

| Gasherbrum II | 8,034 m (26,358 ft) |

1,524 m (5,000 ft) |

7 July 1956 | 2 February 2011 | |||

| Shishapangma | 8,027 m (26,335 ft) |

2,897 m (9,505 ft) |

2 May 1964 | 14 January 2005 | |||

List of climbers of all 14

[edit]There is no single undisputed source or arbitrator for verified ascents of Himalayan eight-thousander peaks.

Various mountaineering journals, including the Alpine Journal and the American Alpine Journal, also maintain extensive records and archives on expeditions to the eight-thousanders, but do not always opine on disputed ascents, and nor do they maintain registers or lists of verified ascents of the eight-thousanders.[1][44]

Elizabeth Hawley's The Himalayan Database,[45] is considered as an important source for verified ascents for the Nepalese Himalayas.[46][47] Online databases of Himalayan ascents pay close regard to The Himalayan Database, including the website AdventureStats.com,[48] and the Eberhard Jurgalski List.[1][44][49]

Verified ascents

[edit]The "No O2" column lists people who have climbed all 14 eight-thousanders without supplementary oxygen.

| Order | Order (No O2) |

Name | Period climbing eight-thousanders |

Born | Age | Nationality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Reinhold Messner | 1970–1986 | 1944 | 42 | |

| 2 | Jerzy Kukuczka | 1979–1987 | 1948 | 39 | ||

| 3 | 2 | Erhard Loretan | 1982–1995 | 1959 | 36 | |

| 4 | [51] | Carlos Carsolio | 1985–1996 | 1962 | 33 | |

| 5 | Krzysztof Wielicki | 1980–1996 | 1950 | 46 | ||

| 6 | 3 | Juanito Oiarzabal | 1985–1999 | 1956 | 43 | |

| 7 | Sergio Martini | 1983–2000 | 1949 | 51 | ||

| 8 | Park Young-seok | 1993–2001 | 1963 | 38 | ||

| 9 | Um Hong-gil | 1988–2001 | 1960[52] | 40 | ||

| 10 | 4 | Alberto Iñurrategi | 1991–2002[53] | 1968 | 33 | |

| 11 | Han Wang-yong | 1994–2003 | 1966 | 37 | ||

| 12 | 5[54] | Ed Viesturs | 1989–2005 | 1959 | 46 | |

| 13 | 6[55][56][57] | Silvio Mondinelli | 1993–2007 | 1958 | 49 | |

| 14 | 7[58] | Iván Vallejo | 1997–2008 | 1959 | 49 | |

| 15 | 8[59] | Denis Urubko | 2000–2009 | 1973 | 35 | |

| 16 | Ralf Dujmovits | 1990–2009 | 1961[60] | 47 | ||

| 17[61] | 9[62] | Veikka Gustafsson | 1993–2009 | 1968 | 41 | |

| 18[63] | Andrew Lock | 1993–2009 | 1961[64] | 48 | ||

| 19 | 10 | João Garcia | 1993–2010 | 1967 | 43 | |

| 20[65] | Piotr Pustelnik | 1990–2010 | 1951 | 58 | ||

| 21[66] | Edurne Pasaban | 2001–2010 | 1973 | 36 | ||

| 22[67] | Abele Blanc | 1992–2011[68][69] | 1954 | 56 | ||

| 23 | Mingma Sherpa | 2000–2011[68] | 1978 | 33 | ||

| 24 | 11 | Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner | 1998–2011[68] | 1970 | 40 | |

| 25 | Vassily Pivtsov | 2001–2011[68] | 1975 | 36 | ||

| 26 | 12 | Maxut Zhumayev | 2001–2011[68] | 1977 | 34 | |

| 27 | Kim Jae-soo | 2000–2011[68] | 1961 | 50 | ||

| 28[70] | 13 | Mario Panzeri | 1988–2012 | 1964 | 48 | |

| 29[71] | Hirotaka Takeuchi [ja] | 1995–2012[71] | 1971 | 41 | ||

| 30 | Chhang Dawa Sherpa | 2001–2013[68] | 1982 | 30 | ||

| 31 | 14 | Kim Chang-ho | 2005–2013[68] | 1970 | 43 | |

| 32 | Jorge Egocheaga | 2002–2014[72] | 1968 | 45 | ||

| 33 | 15 | Radek Jaroš | 1998–2014[68] | 1964 | 50 | |

| 34/35[73] | 16/17[73] | Nives Meroi | 1998–2017[74][75] | 1961 | 55 | |

| 34/35[73] | 16/17[73] | Romano Benet | 1998–2017[74][75][76] | 1962 | 55 | |

| 36 | Peter Hámor | 1998–2017[77][78][79] | 1964 | 52 | ||

| 37 | 18 | Azim Gheychisaz | 2008–2017[80] | 1981 | 37 | |

| 38 | Ferran Latorre | 1999–2017[81] | 1970 | 46 | ||

| 39 | 19 | Òscar Cadiach | 1984–2017[82] | 1952 | 64 | |

| 40 | Kim Mi-gon | 2000–2018[83][84] | 1973 | 45 | ||

| 41 | Sanu Sherpa | 2006–2019[85] | 1975 | 44 | ||

| 42 | Nirmal Purja | 2014–2019[24][86][g] | 1983 | 36 | ||

| 43 | Mingma Gyabu Sherpa | 2010–2019[87][88] | 1989 | 30 | ||

| 44 | Kim Hong-bin | 2006–2021[89][90][91] | 1964 | 57 | ||

| 45 | Nima Gyalzen Sherpa | 2004–2022[92][93] | 1985 | 37 | ||

| 46 | Dong Hong Juan | 2015–2023[94][95] | 1981 | 42 | ||

| 47 | Kristin Harila | 2021–2023[96][97] | 1986 | 37 | ||

| 48 | Sophie Lavaud | 2012–2023[98][99][100][101] | 1968 | 55 | ||

| 49 | Tunç Fındık | 2001–2023[100][101] | 1972 | 51 | ||

| 50 | Tenjen Lama Sherpa | 2016–2023[25][26][102] | 35[103] | |||

| 51 | Gelje Sherpa | 2017–2023[104][105][106] | 1992[104] | 30 | ||

| 52 | Chris Warner | 1999–2023[107] | 1965 | 58 | ||

| 53 | 20 | Marco Camandona | 2000–2024[108][109] | 1970 | 54 | |

| 54 | Naoki Ishikawa | 2001–4 October 2024[110][111] | 1977 | 47 | ||

| 54 | Tracee Metcalfe | 2016–4 October 2024[112][110] | 50[112] | |||

| 54 | 21 | Sirbaz Khan | 2017–4 October 2024[113][114][115][110] | 1987 | 37 | |

| 54 | Dawa Gyalje Sherpa | ?–4 October 2024[110] | ||||

| 54 | 22 | Mingma Gyalje Sherpa | ?–4 October 2024[110] | |||

| 59 | 23 | Mario Vielmo | 1998–9 October 2024[116][117] | 1964 | 60 | |

| 59 | Naoko Watanabe [ja] | 2006–9 October 2024[116][118][119] | 1981 | 42 | ||

| 59 | Adrian Laza | 2016–9 October 2024[116][120] | 1963 | 60 | ||

| 59 | Pasang Nurbu Sherpa | 2016-9 October 2024[116][121][122][123] | ||||

| 59 | Shehroze Kashif | 2019–9 October 2024[116][124][125][126] | 2002 | 22 | ||

| 59 | Dorota Rasińska-Samoćko | 2021–9 October 2024[116][127][128] | ||||

| 59 | Adriana Brownlee | 2021–9 October 2024[116] | 2001 | 23 | ||

| 59 | Nima Rinji Sherpa | 2022–9 October 2024[116][129][130] | 2006[131] | 18 | ||

| 59 | Alasdair McKenzie | 2022–9 October 2024[116] | 2004 | 20 | ||

| 59 | Alina Pekova | 2023–9 October 2024[116][132] | ||||

| 59 | Ko-Erh Tseng | ?–9 October 2024[116] | ||||

| 70 | Mingtemba Sherpa | 2013-2024[133][134] | ||||

| 71 | Tejan Gurung | 2022-2024[135][136] | ||||

| 72 | Pasang Tendi | 2011-2024[137] | ||||

| 73 | Uta Ibrahimi | 2017-2025 [138][139] | 1983 | 42 | ||

| 74 | Saško Kedev | 2009-2025[140] | 1962 | 63 | ||

| 75 | Afsane Hesamifard | 2021-2025[141] | 1976 | 49 | ||

| 76 | Chhiring Sherpa | ?-2025[142] |

Disputed ascents

[edit]Claims have been made for summiting all 14 peaks for which not enough evidence was provided to verify the ascent; the disputed ascent in each claim is shown in parentheses in the table below. In most cases, the Himalayan chronicler Elizabeth Hawley is considered a definitive source regarding the facts of the dispute. Her The Himalayan Database is the source for other online Himalayan ascent databases (e.g. AdventureStats.com).[46][47] The Eberhard Jurgalski List is also another important source for independent verification of claims to have summited all 14 eight-thousanders.[1][44]

| Name and details | Period climbing eight-thousanders |

Born | Age | Nationality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fausto De Stefani (Lhotse 1997)[143] His partner Sergio Martini reclimbed Lhotse in 2000 to verify his 14, see above. |

1983–1998 | 1952 | 46 | |

| Alan Hinkes (Cho Oyu 1990)[144][145] Hinkes rejected Hawley's decision to "unrecognise" his ascent, see "Cho Oyu dispute". |

1987–2005 | 1954 | 53 | |

| Vladislav Terzyul (Shishapangma (West) 2000, Broad Peak 1995[146][147])[148][149] As he did not claim the main summit of Shishapangma, this status is unlikely to change. |

1993–2004 (deceased) |

1953 | 49 | |

| Oh Eun-sun (Kangchenjunga 2009)[150][151][152] As the potential first female climber of all 14, this dispute was followed internationally.[151] |

1997–2010 | 1966 | 44 | |

| Carlos Pauner (Shishapangma 2012)[153] Pauner acknowledged his uncertainty as it was dark; said he might reclimb.[154] |

2001–2013 | 1963 | 50 | |

| Zhang Liang (Shishapangma 2018)[155][156][157] Suspected the 2018 Chinese Shishapangma expedition stopped at central summit. |

2000–2018 | 1964 | 54 |

Verification issues

[edit]A recurrent problem with verification is the confirmation that the climber reached the true peak of the eight-thousander. Eight-thousanders present unique problems in this regard as they are so infrequently summited, their summits have not yet been exhaustively surveyed, and summiting climbers are often suffering the extreme altitude and weather effects of being in the death zone.[1][44]

Cho Oyu for example, is a recurrent problem eight-thousander as its true peak is a small hump about a thirty minutes walk into the large flat summit plateau that lies in the death zone. The true peak is often obscured in very poor weather, and this led to the disputed ascent (per the table above) of British climber, Alan Hinkes (who has refused to re-climb the peak).[158][159] Shishapangma is another problem peak because of its dual summits, which despite being close in height, are up to two hours climbing time apart and require the crossing of an exposed and dangerous snow ridge.[1][160] When Hawley judged that Ed Viesturs had not reached the true summit of Shishapangma (which she deduced from his summit photos and interviews), he then re-climbed the mountain to definitively establish his ascent.[161][1]

In a May 2021 interview with the New York Times, Jurgalski pointed out further issues with false summits on Annapurna I (a long ridge with multiple summits), Dhaulagiri (misleading false summit metal pole), and Manaslu (additional sharp and dangerous ridge to the true summit, like Shishapangma), noting that of the existing 44 accepted claims (as per the table earlier), at least 7 had serious question marks (these were in addition to the table of disputed ascents), and even noting that "It is possible that no one has ever been on the true summit of all 14 of the 8,000-meter peaks".[1] In June 2021, Australian climber Damien Gildea wrote an article in the American Alpine Journal on the work that Jurgalski and a team of international experts were doing in this area, including publishing detailed surveys of the problem summits using data from the German Aerospace Center.[44]

In July 2022, Jurgalski posted conclusions of the team's research (the wider team being of Rodolphe Popier and Tobias Pantel of The Himalayan Database, and Damien Gildea, Federico Bernardi, and Thaneswar Guragai).[2][162] According to their analysis, only three climbers, Ed Viesturs, Veikka Gustafsson and Nirmal Purja have stood on the true summit of all 14 eight-thousanders, and no female climber had yet done so.[2] Viesturs is also the first to have done so without the use of oxygen.[2] Jurgalski allowed for the fact that they had deliberately not stood on the true summit of Kangchenjunga out of religious respect.[2] The team has not formally published their work, and according to Popier, they had not decided about "the best respectful form to present it".[2]

Proposed expansion

[edit]In 2012, to relieve capacity pressure and overcrowding on the world's highest mountain, greater restrictions were placed on expeditions to the summit of Mount Everest.[163] To address the growing capacity constraints, Nepal lobbied the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation (or UIAA) to reclassify five subsidiary summits (two on Lhotse and three on Kanchenjunga), as standalone eight-thousanders, while Pakistan lobbied for a sixth subsidiary summit (on Broad Peak) as a standalone eight-thousander.[164] See table below for list of all subsidiary summits of eight-thousanders.

In 2012, the UIAA initiated the ARUGA Project, with an aim to see if these six new 8,000 m (26,247 ft)-plus peaks could feasibly achieve international recognition.[164] The proposed six new eight-thousander peaks have a topographic prominence above 60 m (197 ft), but none would meet the wider UIAA prominence threshold of 600 m (1,969 ft) (the lowest prominence of the existing 14 eight-thousanders is Lhotse, at 610 metres (2,001 ft)).[165][166] Critics noted that of the six proposed, only Broad Peak Central, with a prominence of 181 metres (594 ft), would even meet the 150 metres (492 ft) prominence threshold to be a British Isles Marilyn.[165] The appeal noted the UIAA's 1994 reclassification of Alpine four-thousander peaks used a prominence threshold of 30 m (98 ft),[h] amongst other criteria; the logic being that if 30 m (98 ft) worked for 4,000 m (13,123 ft) summits, then 60 m (197 ft) is proportional for 8,000 m (26,247 ft) summits.[167]

As of April 2024[update], there has been no conclusion by the UIAA and the proposals appear to have been set aside.

| Proposed new eight-thousander | Height (m) |

Prominence (m) |

Dominance (Prom / Height) as a %[169] |

Dominance classification[169] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broad Peak Central | 8011 | 181 | 2.26 | B2 |

| Kangchenjunga W-Peak (Yalung Kang) | 8505 | 135 | 1.59 | C1 |

| Kangchenjunga S-Peak | 8476 | 116 | 1.37 | C2 |

| Kangchenjunga C-Peak | 8473 | 63 | 0.74 | C2 |

| Lhotse C-Peak I (Lhotse Middle) | 8410 | 65 | 0.77 | C2 |

| Lhotse Shar | 8382 | 72 | 0.86 | C2 |

| K 2 SW-Peak | 8580 | 30 | 0.35 | D1 |

| Lhotse C-Peak II | 8372 | 37 | 0.44 | D1 |

| Everest W-Peak | 8296 | 30 | 0.36 | D1 |

| Yalung Kang Shoulder | 8200 | 40 | 0.49 | D1 |

| Kangchenjunga SE-Peak | 8150 | 30 | 0.37 | D1 |

| K 2 P. 8134 (SW-Ridge) | 8134 | 35 | 0.43 | D1 |

| Annapurna C-Peak | 8051 | 49 | 0.61 | D1 |

| Nanga Parbat S-Peak | 8042 | 30 | 0.37 | D1 |

| Annapurna E-Peak | 8026 | 65 | 0.81 | C2 |

| Shisha Pangma C-Peak | 8008 | 30 | 0.37 | D1 |

| Everest NE-Shoulder | 8423 | 19 | 0.23 | D2 |

| Everest NE-Pinnacle III | 8383 | 13 | 0.16 | D2 |

| Lhotse N-Pinnacle III | 8327 | 10 | 0.12 | D2 |

| Lhotse N-Pinnacle II | 8307 | 12 | 0.14 | D2 |

| Lhotse N-Pinnacle I | 8290 | 10 | 0.12 | D2 |

| Everest NE-Pinnacle II | 8282 | 25 | 0.30 | D2 |

Gallery

[edit]-

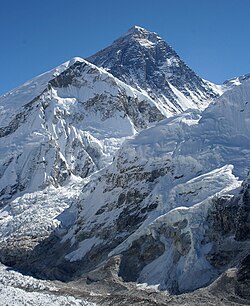

No. 1 – Mount Everest

-

No. 2 – K2

-

No. 3 – Kangchenjunga

-

No. 4 – Lhotse

-

No. 5 – Makalu

-

No. 6 – Cho Oyu

-

No. 7 – Dhaulagiri

-

No. 8 – Manaslu

-

No. 9 – Nanga Parbat

-

No. 10 – Annapurna

-

No. 11 – Gasherbrum I

-

No. 12 – Broad Peak

-

No. 13 – Gasherbrum II

-

No. 14 – Shishapangma

See also

[edit]- List of deaths on eight-thousanders

- List of Mount Everest summiters by number of times to the summit

- List of ski descents of eight-thousanders

- Three Poles Challenge, the North Pole, the South Pole, and Mount Everest

- Explorers Grand Slam, the North Pole, the South Pole, and the Seven Summits

- Volcanic Seven Summits, the highest volcanos on each continent

- Fourteener, peak with at least 14,000 ft. elevation

- List of mountains by elevation

Notes

[edit]- ^ Per The Himalayan Database (HDB) tables, the Climber (or Member) Death Rate is the ratio of deaths above base camp, of all climbers who were hoping to summit and who went above base camp, for 1950 to 2009, and is closer to a true probability of death; the data is only for Nepalese Himalaya. Summary tables from the HDB report for all mountains above 8,000 metres, imply that the death rate for the period 1990 to 2009 (e.g. modern expeditions), is roughly half that of the combined 1950 to 2009 period.[30]

- ^ As recorded by Eberhard Jurgalski

- ^ a b As recorded by Eberhard Jurgalski and being any death (climber or other) above Base Camp.[32]

- ^ This should not be mistaken as being a death rate; it does not imply a probability of death for a climber attempting to climb an eight-thousander as it includes all deaths from all activities undertaken above base camp (e.g. training or reconnaissance trips, camp stocking activities by porters who will not be summiting the mountain, rescue attempts etc.). Thus it compares deaths from the larger group of people who were, and were not, making a summit attempt, with the smaller group who were making a summit attempt. While it is not a probability, the statistic does reflect the ratio of people who died above base camp for each climber who summited.

- ^ a b c d Data is not available for the Karakoram Himalayas

- ^ a b It remains unclear whether George Mallory and Andrew Irvine reached the summit in 1924 or not. For more details, see 1924 British Mount Everest expedition.

- ^ Nirmal Purja climbed all fourteen 8,000m peaks between April 2019 and October 2019, but climbed his first, Dhaulagiri, in 2014.

- ^ The UIAA main list also includes summits that have a prominence far lower than 30 metres.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Branch, John (21 May 2021). "What is a summit: Only 44 people have reached the summit of all 14 of the world's 8,000-meter peaks, according to the people who chronicle such things". New York Times. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Franz, Derek (20 July 2022). "Researchers challenge historical records for 8000-meter peaks". Alpinist. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ "Fast Facts About Nanga Parbat". climbing.about.com. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Herzog, Maurice (1951). Annapurna: First Conquest of an 8000-meter Peak. Translated from the French by Nea Morin and Janet Adam Smith. New York: E.P Dutton & Co. p. 257.

- ^ Yi Wyn Yen (14 November 2004). "Finding China". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ Zawada, Andrzej (1984). "Mount Everest: The First Winter Ascent" (PDF). The Alpine Journal. Translated by Doubrawa-Cochlin, Ingeborga; Cochlin, Peter: 50–59.

- ^ a b c d e Hobley, Nicholas (24 October 2019). "Remembering Jerzy Kukuczka, the legendary Polish mountaineer". PlanetMountain. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ a b Farmer, Ben (16 January 2021). "Former Gurkha Nirmal Purja among Nepalese climbers to complete first winter ascent of deadly K2". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ Isserman, Maurice; Weaver, Stewart (2008). Fallen Giants: A History of Himalayan Mountaineering from the Age of Empire to the Age of Extremes. Yale University Press. pp. 326–327. ISBN 9780300164206. Retrieved 3 July 2025.

- ^ Rossi, Marcello (13 December 2021). ""It's a Suffering Game": Simone Moro and the Fine Art of Climbing 8,000m Peaks in Winter". Climbing. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ PEAKBAGGER: World 7200-meter Peaks (Ranked Peaks have 500 meters of Clean Prominence)

- ^ Stefanello, Vinicio (29 April 2011). "Erhard Loretan, good-bye to a great alpinist". PlanetMountain. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "Oh Eun-Sun report, final: Edurne Pasaban takes the throne". ExplorersWeb. 10 December 2010. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ "Austrian woman claims Himalayas climbing record". BBC News. 23 August 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ "Austrian is first woman to scale 14 peaks without oxygen". AsiaOne. 30 August 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ "Italians become first couple to scale all eight-thousanders". ansa.it. 11 May 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ a b Stefanello, Vinicio (11 May 2017). "Nives Meroi and Romano Benet summit Annapurna, their 14th 8000er". PlanetMountain. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ "Alpinismo, il record di Meroi-Benet: è italiana la prima coppia su tutti gli Ottomila". 11 May 2017.

- ^ "Most climbs over 8,000 metres". Guinness Book of Records. 23 May 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ Sharma, Gopal (21 July 2022). "Nepali Sherpa sets climbing record on Pakistan mountain". Reuters. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ "World record: Sanu Sherpa has climbed all 14 eight-thousanders twice". LACrux. 28 July 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ Atwal, Sanj (3 December 2021). "14 Peaks: All the records Nims Purja broke in new Netflix documentary". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ "Nirmal Purja: Ex-soldier climbs 14 highest mountains in six months". BBC News. 29 October 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

A Nepali mountaineer and former British Marine has climbed the world's tallest 14 peaks in six months - beating an earlier record of almost eight years.

- ^ a b Freddie Wilkinson. "Nepal climber makes history speed climbing world's tallest peaks". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

On October 29th, Nirmal Purja Magar announced via Instagram that he had summited China's Shishapangma. This marked the fourteenth 8,000-meter peak he had climbed in seven months and the completion of an extraordinary project to speed climb the world's tallest mountains in rapid succession.

- ^ a b Arnette, Alan (27 July 2023). "K2 2023 Coverage: Kristin Harila gets K2 for her Last 8000er". alanarnette.com. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Kristin Harila, Tenjen Sherpa world's fastest to climb 14 peaks in 92 days". The Himalayan Times. 27 July 2023. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Eberhard Jurgalski [in German]. "General Info". 8000ers.com. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ Clarke, Owen (2 April 2025). "Has K2—the Savage Mountain—Been Tamed?". Climbing. Retrieved 20 April 2025.

- ^ a b c "DAILY CHART: Stairway to heaven, how deadly are the world's highest mountains?". The Economist. 29 March 2013.

For every three thrill-seekers that make it safely up and down Annapurna I, one dies trying, according to data from Eberhard Jurgalski of website 8000ers.com, collected in his forthcoming book "On Top of the World: The New Millennium", co-authored by Richard Sale.

- ^ a b c d e f g Elizabeth Hawley; Richard Sailsbury (2011). "The Himalaya by the Numbers: A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya" (PDF). p. 129.

Table D-3: Deaths for peaks with more than 750 members above base camp from 1950–2009

- ^ "Himalayan Death Tolls". The Washington Post. 24 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Eberhard Jurgalski [in German]. "Fatalities tables". 8000ers.com. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

Included are only fatalities from, at or above BC or caused from there. Fatalities on approach or return marches are not listed.

- ^ a b Armstrong, Martin (10 December 2021). "Deadly Peaks". Statista. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Whitman, Mark (22 December 2020). "Eight Thousanders – The Complete 8000ers Guide". MountainIQ. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ "Deadliest mountain to climb". Guinness Book of World Records. 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ a b PeakBagger: World 8000–metre Peaks

- ^ "Mount Everest is two feet taller, China and Nepal announce". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 8 December 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ "K2 lies in Pakistan, near the northern border with China". BBC News. 26 July 2014.

- ^ a b "All-Nepali winter first on K2". Nepali Times. 16 January 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ a b Naresh Koirala (16 January 2022). "A matter of pride". The Kathmandu Times. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ a b Tom Robbins (1 January 2022). "Life lessons from mountaineer Nirmal Purja, of Netflix's 14 Peaks fame". CNA Luxury. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ [39][40][41]

- ^ Harding, Luke (13 July 2000). "Climbers banned from sacred peak". the Guardian. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Gildea, Damien (June 2021). "THE 8000-ER MESS". American Alpine Journal. 62 (94). American Alpine Club. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ Elizabeth Hawley; Richard Salisbury (2018). "The Himalayan Database, The Expedition Archives of Elizabeth Hawley". The Himalayan Database.

- ^ a b If a mountaineer wants worldwide recognition that they have reached the summit of some of the most formidable mountains in the world, they will need to get the approval of Elizabeth Hawley."Elizabeth Hawley, unrivalled Himalayan record keeper". BBC News. 29 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Elizabeth Hawley, Who Chronicled Everest Treks, Dies at 94". The New York Times. 26 January 2018.

- ^ "High Altitude Mountaineering statistics". AdventureStats.com. 2018. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014.

- ^ "Climbers who have ascended to the summits of all of the world's 14 mountains over 8000 metres". 8000ers.com (Eberhard Jurgalski). 2018.

- ^ Eberhard Jurgalski [in German] (26 May 2012). "Climbers – First 14". 8000ers.com. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ Carlos Carsolio required emergency oxygen on his descent from Makalu in 1988.

- ^ EverestNews2004.com, News (age calculated: in 2004 Hong-Gil Um was 44). "Mr. Um Hong Gil has bagged his 15th 8000 meter peak". Archived from the original on 21 June 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Kukuxumusu, Spanish News. "Alberto Iñurrategi achieves his fourteenth "eight thousand meters"". Archived from the original on 21 June 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ^ "Best of ExplorersWeb 2005 Awards: Ed Viesturs and Christian Kuntner". Mounteverest.net. Archived from the original on 22 December 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

...the American climber became one of only five men in the world to accomplish the quest entirely without supplementary oxygen.

- ^ Mounteverest.net. "The wolf is back: Gnaro bags Baruntse". Archived from the original on 28 October 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

Last year, Silvio 'Gnaro' Mondinelli broke the haunted 13 when he summited the last peak on his list of 14, 8000ers – becoming only the 6th mountaineer in the world to have bagged them all without supplementary oxygen.

- ^

"The day after: Silvio Mondinelli, Broad Peak and all 14 8000m summits". PlanetMountain.com. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

13/07 interview with Silvio Mondinelli after the summit of his 14th 8000m peak without supplementary oxygen.

- ^ "The 14th knight: Ecuadorian Ivan Vallejo is ready to continue". Mounteverest.net. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

Implied in text: ...Following Italian Silvio "Gnaro" Mondinelli last year and American Ed Viesturs in 2005, Ivan also became only the seventh mountaineer in the world to have done them all without supplementary oxygen.

- ^ "The 14th knight: Ecuadorian Ivan Vallejo is ready to continue". Mounteverest.net. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

...Ivan also became only the seventh mountaineer in the world to have done them all without supplementary oxygen.

- ^ "Denis Urubko, Cho Oyu and all 14 8000m peaks". PlanetMountain.com. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ "Ralf Dujmovits". Ralf-dujmovits.de. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ^ "GI summits - Veikka Gustafsson completes the 14x8000ers list!". Explorersweb.com. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ "Best of ExplorersWeb 2009 Awards: the 14x8000ers". Explorersweb.com. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ "Summit 8000 – Andrew Lock's quest to climb all fourteen of the highest mountains in the world". Andrew-lock.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ^ "Australia's Most Accomplished Mountaineer". Andrew Lock. 2 October 2009. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ^ "Piotr Pustelnik summits Annapurna – bags the 14x8000ers!". Explorersweb.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Shisha Pangma: Edurne Pasaban summits – completes the 14x800ers". Explorersweb.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Abele Blanc summits Annapurna and all 8000ers". Planetmountain.com. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Climbers - First 14, updated table on 8000ers.com". 8000ers.com. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Everest – Mount Everest by climbers, news". Mounteverest.net. 18 May 2005. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ "Mario Panzeri: sono in cima! E finalmente sono 14 ottomila". Montagna.tv. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ a b "日本人初の快挙、8000m峰14座登頂 竹内洋岳". Nikkei.com. 26 May 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Climbers – First 14". 8000ers.com. 13 August 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d Nives Meroi and Romano Benet climbed all the Eight-thousanders together, it wasn't revealed if one of them climbed the last peak a few moments before the other, thus they share the same position

- ^ a b "Nives Meroi and Romano Benet summit Annapurna, their 14th 8000er". PlanetMountain.com. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ a b "Nives Meroi in Roman Benet preplezala 14 osemtisočakov". Sta.si (in Slovenian). Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ "Slovenec s 15. osemtisočaka". Delo.si (in Slovenian). Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ "Pokoril všetky osemtisícovky". skrsi.rtvs.sk. 16 May 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ "È vetta per Peter Hamor. Con il Dhaulagiri sono 14 anche per lui" (in Italian). www.montagna.tv. 15 May 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Tom Nicholson (4 June 1998). "HZDS flag flies from Everest summit". spectator.sme.sk. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ "قیچیساز حماسه ساز شد/کوهنورد تبریزی به هشت هزاریها پیوست". yjc. 19 May 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ "Ferran Latorre completa los catorce ochomiles en el Everest" (in Spanish). desnivel.com. 27 May 2017. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ "Cadiach, camino del campo 3 tras coronar el Broad Peak" (in Spanish). La Vanguardia. 27 July 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ^ "김미곤 히말라야 14봉 등정 보고회 열려" (in Korean). Mountain Journal. 27 July 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "South Korean Climbs Nanga Parbat, Completes 8,000ers". Gripped. 12 July 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ "Sanu Sherpa becomes third Nepali to complete 14 peaks as Sergi Mingote scales 7 mountains in 444 days". The Himalayan Times. 3 October 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Dream Wanderlust (24 May 2019). "Nirmal Purja summits 5th eight-thousander in 12 days, ends 1st phase of 'Project Possible'". Dreamwanderlust.com.com. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- ^ "Reflections While Waiting for News from Shishapangma". Explorersweb.com. 29 October 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Kennedy, Merrit (29 October 2019). "Nepalese Climber Summits World's 14 Highest Peaks in 6 Months, Smashing Record". NPR.

- ^ Munir Ahmed (20 July 2021). "South Korean missing after fall while scaling Pakistani peak". Times Union. Archived from the original on 20 July 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "Fingerless Korean goes missing after achieving the feat of climbing all 14 Himalayan peaks". The Korea Times. 20 July 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Stefan Nestler (10 July 2019). "Kim Hong-bin: Without fingers on 13 eight-thousanders". Adventure Mountain. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "Nima Gyalzen Sherpa becomes the 6th Nepali in the 14 Peaks club". everestchronicle.com. 11 August 2022. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ "Nima Gyalzen completes 14 peaks as Grace Tseng, Kristin Harila scale G-I". thehimalayantimes.com. 11 August 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ Benavides, Angela (26 April 2023). "Dong Hong Juan Climbs Shishapangma; May Be the First Woman to Summit all 14 8,000'ers » Explorersweb". Explorersweb. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ "China's Dong becomes first woman to conquer all 14 peaks above-8,000m". Chinadaily.com. 1 May 2023. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ "Kristin Harila scales Mount Shishapangma". everestchronicle.com. 26 April 2023. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ "Kristin Harila completes 14 peaks as she scales Cho Oyu". The Himalayan Times. 3 May 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "Sophie Lavaud, first French mountaineer to climb all the peaks over 8,000 m on the planet – Liberation". Time News. 26 June 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Sophie Lavaud becomes first French person to climb world's highest peaks". RFI. 26 June 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ a b Benavides, Angela (26 June 2023). "Nanga Parbat Summits » Explorersweb". Explorersweb. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ a b "A 17-year-old Nepali teenager scales the 'Killer Mountain'". Everest Chronicle. 26 June 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ "Seven Summit Treks Tenjen Sherpa (Lama)". Archived from the original on 28 July 2023. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ Gopal Sharma (27 July 2023). "Norwegian woman, Nepali sherpa become world's fastest to climb all 14 tallest peaks". Reuters. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ a b Dream Wanderlust (30 March 2021). "After K2 in Winter, Gelje Sherpa (28) aims to become the youngest to climb all 14 8Ks". DreamWanderlust.com. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ^ "Gelje Sherpa joins the 14 peak club with summit on Cho Oyu; Nima Rinji sets youngest climber record". everestchronicle.com. 6 October 2023. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ "Nepali and Pakistani Climbers Make History on Cho Oyu". whatthenepal.com. 6 October 2023. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ Stern, Jake (22 September 2023). "This Climber Just Became the Second American to climb Every 8,000 Meter Peak". Outside. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ "Camandona completa la collezione degli ottomila, "quasi un gioco" - Notizie - Ansa.it". Agenzia ANSA (in Italian). 30 July 2024. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ Annapurna, Kris (30 July 2024). "More Summits on K2, Broad Peak, Gasherbrum II". ExplorersWeb. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Imagine Nepal: 11 climbers reach the true summit, where five of them complete all 14 highest peaks, and Mingma G sets an oxygen-free record". imagine-nepal.com. 4 October 2024. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ "写真家・石川直樹さん、ヒマラヤ8000m峰全14座を制覇…最後のシシャパンマに登頂". Yomiuri Shimbun. 7 October 2024. Archived from the original on 2 December 2024. Retrieved 8 March 2025.

- ^ a b Benavides, Angela (7 October 2024). "Tracee Metcalfe Becomes First U.S. Woman to Climb the World's Highest Peaks » Explorersweb". Explorersweb. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ "Sirbaz Khan becomes first Pakistani to conquer 14 world's highest peaks". www.geosuper.tv. Retrieved 4 October 2024.

- ^ "Sirbaz to become first Pakistani to summit 14 eight-thousanders". 3 October 2024. Retrieved 4 October 2024.

- ^ "Sirbaz Khan to Become First Pakistani Mountaineer to Summit All 14 Eight-Thousanders". 3 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Seven Summit Treks announces 100% summit success on Shisha Pangma". thehimalayantimes.com. 9 October 2024. Archived from the original on 5 November 2024. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ "Mario Vielmo come Messner, l'alpinista ha conquistato anche l'ultimo Ottomila" (in Italian). Corriere della Sera. 10 October 2024. Retrieved 10 October 2024.

- ^ "Face the Mountains, Face Yourself: Watanabe Naoko / Mountaineer, Nurse". NHK. Archived from the original on 6 February 2025. Retrieved 6 February 2025.

- ^ "日本人女性初「8000m峰」全14座を制覇 登山家・渡邊直子さん(43)衝撃の苦労話も". Yahoo Japan News. Archived from the original on 6 February 2025. Retrieved 6 February 2025.

- ^ "Reuşită în Himalaya. Adrian Laza, alt optmiar cucerit. "Este un alt fel de om. Nu face parte din această lume" FOTO". adevarul.ro (in Romanian). 30 May 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ https://www.nimsdai.com/post/breaking-kathmandu-celebration-for-nimsdai-team-and-fellow-record-breaking-

- ^ "Tenjen, Ming Temba, And Pasang Nurbu Sherpa Completed Ascent Of Mt Manaslu". Tourism Mail. 22 September 2023. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "Nima Rinji Sherpa becomes youngest to summit 14 highest peaks". Everest Chronicles. 9 October 2024. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "Shehroze Kashif sets record as youngest Pakistani to summit top 14 peaks". The Express Tribune. 9 October 2024. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "Shehroze Kashif becomes youngest Pakistani to summit world's 8,000m peaks". DAWN.COM. 9 October 2024. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "Shehroze Kashif Becomes Youngest Pakistani To Summit All 8,000M Mountains". The Friday Times. 9 October 2024. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ Maciej Skorupa (9 October 2024). "Pierwsza Polka z Koroną Himalajów i Karakorum! To się naprawdę stało, brawo!" (in Polish). przegladsportowy.onet.pl. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ "Shisha Pangma: Dorota Rasińska-Samoćko wchodzi na szczyt i zdobywa Koronę Himalajów i Karakorum" (in Polish). wspinanie.pl. 9 October 2024. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ "Nima Rinji becomes world's youngest to scale all 14 peaks". The Himalayan Times. 9 October 2024. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ Benavides, Angela (28 September 2024). "No Oxygen Claims Create Uncertainty on Shisha Pangma » Explorersweb". Explorersweb. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ "Youngest person to climb the higher 8,000ers (male)". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 6 December 2024. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "More than a dozen newcomers to the list of climbers with all 14 eight-thousanders". abenteuer-berg.de. 9 October 2024. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ "Nimsdai - BREAKING: Kathmandu celebration for Nimsdai team and fellow record-breaking Nepalis". www.nimsdai.com. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "Adriana Brownlee becomes youngest female climber to complete 14 peaks". Everest Chronicles. 9 October 2024. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ https://www.si.com/onsi/adventure/mountaineering-feed-page/british-army-veterans-make-mountaineering-history-with-summit-of-shishapangma-

- ^ https://www.si.com/onsi/adventure/mountaineering-feed-page/celebrations-held-in-kathmandu-recognizing-nepalis-mountaineers-accomplishments

- ^ https://www.si.com/onsi/adventure/mountaineering-feed-page/celebrations-held-in-kathmandu-recognizing-nepalis-mountaineers-accomplishments-

- ^ Sherifi, Elife (23 July 2019). "Uta Ibrahimi 'pushton' vargmalet e Pakistanit, vajza e parë në histori nga Ballkani". 2LONLINE (in Albanian). Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "Uta Ibrahimi, the first Kosovar to conquer the Himalayas". Independent Balkan News Agency. 22 May 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "From Macedonia to the Summits: Dr. Kedev Joins Mountaineering's Elite Club". Everest Today. Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ "Hesamifard becomes first Iranian woman to summit all 14 peaks above 8000m". TehranTimes.com. Retrieved 14 October 2025.

- ^ "Hesamifard becomes first Iranian woman to summit all 14 peaks above 8000m". TehranTimes.com. Retrieved 14 October 2025.

- ^ Elizabeth Hawley (2014). "Seasonal Stories for the Nepalese Himalaya 1985–2014" (PDF). The Himalayan Database. p. 274.

But a South Korean climber, who followed in their footprints on the crusted snow three days later [in 1997] in clearer weather, did not consider that they actually gained the top. While [Sergio] Martini and [Fausto] De Stefani indicated they were perhaps only a few meters below it, Park Young-Seok claimed that their footprints stopped well before the top, perhaps 30 meters below a small fore-summit and 150 vertical meters below the highest summit. Now in 2000 [Sergio] Martini was back again, and this time he definitely summited Lhotse.

- ^ AdventureStats.net, Official records. "Climbers that have summited 10 to 13 of the 14 Main-8000ers". Archived from the original on 3 August 2007. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ^ Elizabeth Hawley (2014). "Seasonal Stories for the Nepalese Himalaya 1985–2014" (PDF). The Himalayan Database. p. 347.

But his claim to have now climbed all 8000ers is open to question. In April 1990 he and others reached the summit plateau of Cho Oyu. It was misty so they could not see well; nine years later Hinkes said he had "wandered around for a while" in the summit area but could see very little and eventually descended to join the others, one of whom said they had not reached the top.

- ^ "Vladislav Terz". www.russianclimb.com. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ^ "AdventureStats – by Explorersweb". www.adventurestats.com. Archived from the original on 3 August 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ^ Russianclimb.com, Mountaineering World of Russia & CIS. "Vladislav Terzyul, List of ascents". Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ^ "Sad results on Makalu and Unanswered Questions: 1 missing climber and 1 passed away on Makalu". Everestnews2004.com. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Everest K2 News ExplorersWeb – More dark clouds mounting on Anna summit push; Miss Oh's Kanchen summit "disputed" after renewed accusations". Explorersweb.com. 26 April 2010. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ a b "New doubts over Korean Oh Eun-Sun's climbing record, Hawley to investigate". BBC News. 27 August 2010.

- ^ What would appear to be the most serious blow to Miss Oh, on 26 August this year the Korean Alpine Federation, the nation's largest climbing association, concluded that Miss Oh had not reached the top of Kangchenjunga."Seasonal Stories for the Nepalese Himalaya 1985–2014" (PDF). Elizabeth Hawley. 2014. p. 394.

- ^ "Desnivel; Carlos Pauner consigue la cima del Everest". Desnivel.com. Archived from the original on 23 October 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ "Carlos Pauner is not sure if they hit the top of the Shisha Pangma (8,027)". lainformacion.com. 18 February 2016. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ "CCTV; 罗静等23名中国登山者登顶希夏邦马峰". CCTV. 29 September 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ "The Himalayan Times; Four Chinese climbers complete all 14 peaks above 8,000m this autumn". The Himalayan Times. 29 September 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ "Luo Jing no alcanzó la cima principal del Shisha Pangma" [Luo Jing did not reach the main peak of the Shishapangma] (in Spanish). Desnivel.com. 4 October 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ I have summited Cho Oyu 4 times and will be heading for my fifth this coming season. Each time I have watched the Koreans and Japanese go only to where they can see Everest, not the summit because they know this is what will be asked."Cho Oyu summit: Where is it exactly". Explorersweb.com. September 2017.

- ^ Many people who climb Cho Oyu in Tibet stop at a set of prayer flags with views of Everest and believe they’ve reached the top, unaware they still have to walk for 15 minutes across the summit plateau until they can see the Gokyo Lakes in Nepal."When is a summit not a summit?". Mark Horrell. 12 November 2014.

- ^ "Asia, Tibet, Cho Oyu and Shisha Pangma Central (West) Summit". American Alpine Journal. 1991.

- ^ Keeper of the Mountains: The Elizabeth Hawley Story. Rocky Mountain Books. 5 October 2012. pp. 185–195. ISBN 978-1927330159.

- ^ Dewan Rai (19 September 2022). "The Debate Over Manaslu's Summit Is Over. Now, Hundreds of Climbers Want to Reach It". outsideonline.com. Retrieved 4 November 2024.

- ^ Richard Gray (23 August 2013). "The new peaks opened as alternatives to Mount Everest". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

Nepal

- ^ a b c Navin Singh Khadka (18 October 2013). "Nepal mountain peak expansion bid stalls". BBC News.

- ^ a b "Do we really need more 8000m peaks". Mark Horrell. 23 October 2013.

The most prominent one, Broad Peak Central is just 196m high and the least prominent, Lhotse Middle, is a meagre 60m. To put this in context, the highest mountain in Malta is 253m, while the Eiffel Tower stands a whopping 300m.

- ^ "A funny name for a mountain". Mark Horrell. 4 June 2014.

- ^ "UIAA Mountain Classification: 4,000ERS OF THE ALPS". UIAA. March 1994. Archived from the original on 9 September 2020. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

Topographic criterium: for each summit, the level difference between it and the highest adjacent pass or notch should be at least 30 m (98 ft) (calculated as average of the summits at the limit of acceptability). An additional criterium can be the horizontal distance between a summit and the base of another adjacent 4000er.

- ^ Eberhard Jurgalski [in German]. "Subsidiary Peaks". 8000ers.com. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

There are several different subsidiary peaks! Here are the geographical facts, from the one "relative independent Main-Peak" (EU category B) over the important subsidiary peaks (C) to the major notable points (D1) Especially the last category is just guessed by contours or from photographs.

- ^ a b Eberhard Jurgalski [in German]. "Dominance". 8000ers.com. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

Accordingly, the author introduced altitude classes (AC) and a proportional prominence, which he named orometrical dominance (D). D is calculated easily but fittingly: (P/Alt) x 100. Thus, it indicates the percentage of independence for every elevation, no matter what the altitude, prominence or mountain type it is. From a scientific point of view, altitude could be seen as the thesis, prominence as the antithesis, whereas dominance would be the synthesis.

External links

[edit]- 8000ers.com, a site dedicated to statistics on 8000m peaks and climbs

- PeakBagger.com World 8000-meter Peaks, a database of global peaks

- The Himalayan Database, statistics on Nepalese Himalayan (but not Pakistan Himalaya) climbs from 1905 to 2018

- AdventureStats.com (High Altitude Mountaineering), a site dedicated to recording adventure statistics

- NASA Earth Observatory: The Eight-Thousanders

Eight-thousander

View on Grokipedia| Rank | Mountain | Height (m) | Location | First Ascent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mount Everest | 8,849 | Nepal/China | 1953 (Edmund Hillary, Tenzing Norgay) |

| 2 | K2 | 8,611 | Pakistan/China | 1954 (Achille Compagnoni, Lino Lacedelli) |

| 3 | Kangchenjunga | 8,586 | Nepal/India | 1955 (Joe Brown, George Band et al.) |

| 4 | Lhotse | 8,516 | Nepal/China | 1956 (Fritz Luchsinger, Ernst Reiss) |

| 5 | Makalu | 8,485 | Nepal/China | 1955 (Jean Couzy et al.) |

| 6 | Cho Oyu | 8,188 | Nepal/China | 1954 (Herbert Tichy et al.) |

| 7 | Dhaulagiri | 8,167 | Nepal | 1960 (Kurt Diemberger et al.) |

| 8 | Manaslu | 8,163 | Nepal | 1956 (Toshio Imanishi et al.) |

| 9 | Nanga Parbat | 8,126 | Pakistan | 1953 (Hermann Buhl) |

| 10 | Annapurna I | 8,091 | Nepal | 1950 (Maurice Herzog, Louis Lachenal) |

| 11 | Gasherbrum I | 8,080 | Pakistan/China | 1958 (Pete Kauffman, Andrew Schoening) |

| 12 | Broad Peak | 8,051 | Pakistan/China | 1957 (Marcus Schmuck et al.) |

| 13 | Gasherbrum II | 8,035 | Pakistan/China | 1956 (Fritz Moravec et al.) |

| 14 | Shishapangma | 8,027 | China | 1964 (Hsu Ching et al.) |

Definition and Overview

Classification Criteria

An eight-thousander is defined as a mountain whose summit rises more than 8,000 meters (26,247 feet) above sea level, a threshold that identifies the highest peaks on Earth.[6] Exactly 14 such peaks are universally recognized, all situated within the Himalayan and Karakoram ranges of central Asia.[7] In February 2025, Nepal recognized six additional subsidiary peaks over 8,000 m as eight-thousanders for permit and national purposes, though the international standard remains 14 independent peaks. This classification excludes subsidiary summits or sub-peaks unless they demonstrate sufficient topographic independence, typically requiring a prominence of at least 500 meters from their connecting col to qualify as a distinct mountain.[6] The term "eight-thousander" originated in the mid-20th century among the international mountaineering community, particularly in German-speaking Alpine circles where it is known as Acht-Tausender, to collectively describe these elite summits as expeditions targeted them following World War II.[8] It reflects a practical grouping for climbers and geographers focused on the world's most extreme altitudes, emphasizing their shared challenges in the "death zone" above 8,000 meters. Heights are determined using orthometric elevation, which measures vertical distance above mean sea level, accounting for gravitational variations and Earth's curvature.[9] Early assessments relied on 19th-century trigonometric surveys, such as India's Great Trigonometrical Survey (initiated in 1802), which calculated peak elevations from distant observation stations using angular measurements and corrections for atmospheric refraction.[10] Post-World War II advancements, including closer-range triangulation by the Survey of India in the 1950s, refined these figures—for instance, revising Mount Everest's height from 29,002 feet to 29,028 feet.[11] Contemporary verifications incorporate Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) and GPS technology for higher precision, as seen in the 2020 Sino-Nepalese joint survey that confirmed Everest at 8,848.86 meters.[12]Significance in Mountaineering

The eight-thousanders hold an iconic status in mountaineering as the pinnacle of high-altitude challenges, attracting elite climbers worldwide since the mid-20th century due to their extreme elevations and harsh conditions within the "death zone," where oxygen scarcity severely limits human endurance.[6] These 14 peaks, all located in the Himalayas and Karakoram ranges, embody the ultimate test of physical, mental, and technical prowess, pushing boundaries of what is humanly possible in extreme environments.[13] Following World War II, the "Golden Age" of Himalayan mountaineering emerged, with expeditions to eight-thousanders symbolizing the exploration of human limits and serving as arenas for national prestige; the 1953 British ascent of Everest by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay, for instance, marked a triumphant postwar achievement that captivated global attention and boosted national morale.[14] This era transformed these mountains from remote mysteries into symbols of international ambition and technological ingenuity in climbing.[14] In contemporary mountaineering, eight-thousanders continue to draw adventurers for record-breaking feats, including the fastest traversals of all 14 peaks and ascents without supplemental oxygen, as demonstrated by climbers like Nirmal Purja, who completed the project in under seven months in 2019.[15] They also host commercial expeditions, enabling broader access while raising ethical debates on safety and sustainability. Economically, these activities significantly bolster tourism in Nepal and Pakistan, with permit royalties generating around $5-6 million annually as of 2024, contributing to broader mountain tourism revenue exceeding $800 million in 2023.[16][17] Philosophically, the eight-thousanders evoke profound themes of adventure, inherent risk, and environmental stewardship, profoundly influencing mountaineering literature and discourse on human-nature interactions; Jon Krakauer's 1997 account Into Thin Air, detailing the 1996 Everest disaster, exemplifies this by critiquing commercialization and the perils of hubris in high-altitude pursuits. Statistically, as of 2025, over 15,000 successful summits have been recorded across the 14 peaks, underscoring their enduring allure, yet only around 60 climbers have verified completions of the full set, highlighting the extraordinary rarity of the endeavor.[13][18]Geography and Peaks

Locations and Mountain Ranges

The fourteen eight-thousanders are exclusively located in the Himalayan and Karakoram mountain ranges of central Asia. Ten of these peaks are situated in the Himalayas, spanning the territories of Nepal, India, and China (including the Tibet Autonomous Region), while the remaining four lie in the Karakoram range along the border between Pakistan and China.[6] Nepal is home to eight eight-thousanders, more than any other country, including peaks such as Everest (shared with China), Lhotse (shared with China), Makalu (shared with China), Cho Oyu (shared with China), Kangchenjunga (shared with India), Manaslu, Dhaulagiri, and Annapurna. Pakistan hosts five, comprising K2 (shared with China), Nanga Parbat, Gasherbrum I (shared with China), Broad Peak (shared with China), and Gasherbrum II (shared with China). China possesses eight through shared borders with Nepal and Pakistan, in addition to Shishapangma, which is entirely within its Tibet Autonomous Region.[19][7] India shares one, Kangchenjunga, along its border with Nepal.[7] Notable clusters include the Everest-Lhotse massif in Nepal's Sagarmatha National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site encompassing these adjacent peaks. In Pakistan, the Gasherbrum group—consisting of Gasherbrum I, Gasherbrum II, and Broad Peak—forms a prominent cluster in the remote Baltoro Glacier region of the Karakoram. Many eight-thousanders straddle international borders, creating complexities for climbers, such as the need for permits from multiple governments; for instance, Shishapangma requires approval solely from Chinese authorities due to its location deep within Tibet.[20] Accessibility to these peaks typically begins with remote base camps reached via multi-day treks. The South Everest Base Camp, located at 5,364 meters in Nepal, serves as the primary staging area for Everest and Lhotse expeditions. Similarly, K2's base camp is accessed via the Godwin-Austen Glacier in Pakistan, a rugged icefield in the Baltoro region that demands technical glacier travel.[21][22]Heights and Rankings

The 14 eight-thousanders are ranked by their summit elevations, all exceeding 8,000 meters above sea level, as recognized by the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation (UIAA).[7] These heights are derived from historical surveys, with updates incorporating modern GPS and photogrammetry techniques; for instance, Mount Everest's elevation was precisely measured at 8,848.86 meters in a 2020 joint expedition by Nepal and China using GNSS technology. Heights for the remaining peaks stem from mid-20th-century expeditions and subsequent validations, showing minor discrepancies of a few meters attributable to variable snow accumulation, glacial retreat, or measurement methodologies, though the overall ranking has remained stable since the 1950s. All peaks exhibit substantial topographic prominence, defined as the vertical distance from the lowest contour line encircling the summit without higher intervening terrain; K2, for example, boasts a prominence of 4,020 meters, underscoring its isolation in the Karakoram range. The following table presents the ranked list, including elevations, primary locations (straddling international borders where applicable), and the year of first documented ascent.| Rank | Peak | Height (m) | Location | First Ascent Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mount Everest | 8,848.86 | Nepal/China (Himalayas) | 1953 |

| 2 | K2 | 8,611 | Pakistan/China (Karakoram) | 1954 |

| 3 | Kangchenjunga | 8,586 | Nepal/India (Himalayas) | 1955 |

| 4 | Lhotse | 8,516 | Nepal/China (Himalayas) | 1956 |

| 5 | Makalu | 8,485 | Nepal/China (Himalayas) | 1955 |

| 6 | Cho Oyu | 8,188 | Nepal/China (Himalayas) | 1954 |

| 7 | Dhaulagiri | 8,167 | Nepal (Himalayas) | 1960 |

| 8 | Manaslu | 8,163 | Nepal (Himalayas) | 1956 |

| 9 | Nanga Parbat | 8,126 | Pakistan (Himalayas) | 1953 |

| 10 | Annapurna I | 8,091 | Nepal (Himalayas) | 1950 |

| 11 | Gasherbrum I | 8,080 | Pakistan/China (Karakoram) | 1958 |

| 12 | Broad Peak | 8,051 | Pakistan/China (Karakoram) | 1957 |

| 13 | Gasherbrum II | 8,035 | Pakistan/China (Karakoram) | 1956 |

| 14 | Shishapangma | 8,027 | China (Himalayas) | 1964 |

Climbing History

Early Expeditions and Attempts

The exploration of eight-thousanders began with systematic surveys in the 19th century, primarily driven by British colonial efforts to map the Indian subcontinent and the Himalayan ranges. The Great Trigonometrical Survey of India, initiated in 1802 under William Lambton and continued by George Everest, employed triangulation methods to measure vast territories, identifying numerous high peaks in the process. By the 1850s, surveyors had cataloged several prominent summits, with the highest initially labeled as Peak XV during observations from distant stations in the Terai region. In 1856, Indian mathematician Radhanath Sikdar's calculations confirmed Peak XV's height at approximately 29,002 feet (8,840 meters), marking it as the world's tallest mountain, though it was not yet named Mount Everest.[23] These surveys also pinpointed other eight-thousanders, such as Kanchenjunga (Peak IX) and Dhaulagiri (Peak XIV), providing the foundational geographical data that would guide future mountaineering endeavors.[24] In the early 20th century, reconnaissance expeditions shifted focus toward actual climbing attempts, with European teams targeting the formidable Himalayan giants despite limited technology and harsh conditions. German mountaineers, seeking national prestige, launched multiple assaults on Nanga Parbat starting in the 1920s, viewing it as a symbol of untamed challenge. The 1932 German-American expedition, led by Willy Merkl, reached altitudes of about 7,000 meters via the Rakhiot Face but retreated due to avalanches and exhaustion, marking the first major organized push on the peak without fatalities.[25] This was followed by the ill-fated 1934 return under Merkl, which advanced to 7,500 meters before a catastrophic blizzard trapped the team, resulting in 16 deaths—including Merkl himself and several Sherpas—highlighting the peak's lethal weather patterns.[26] Meanwhile, British efforts centered on Everest, with the 1921 reconnaissance expedition under Charles Howard-Bury mapping routes from Tibet and confirming the North Col as a viable approach, though no summits were attempted.[27] The 1922 expedition, led by Charles Bruce, pushed to 8,170 meters but ended in tragedy when an avalanche killed seven Sherpa porters, underscoring the logistical perils of high-altitude portering. The 1924 attempt saw George Mallory and Andrew Irvine vanish near the summit during their bid from 8,170 meters, fueling enduring speculation about whether they reached the top, while the team overall turned back amid oxygen shortages and storms.[27] Further British probes in 1933, 1935, and 1938 reached similar heights but failed due to weather and physiological limits, establishing Everest as the ultimate test of endurance.[27] Interwar period highlights included pioneering efforts by unconventional figures that broadened participation in Himalayan exploration. In 1902, British climber and occultist Aleister Crowley joined Oscar Eckenstein's expedition to K2, the first serious attempt on the peak, approaching via the southeast ridge and establishing camps up to 6,500 meters before abandoning the climb due to frostbite, dysentery, and internal conflicts among the seven-member team.[28] This venture, though unsuccessful, demonstrated K2's extreme technical demands and isolated nature. Women explorers also emerged, with American Fanny Bullock Workman conducting extensive traverses in the Karakoram and Punjab Himalaya; in 1906, she and her husband William ascended Pinnacle Peak (6,930 meters) in the Nun Kun massif, setting a women's altitude record at the time and mapping glaciers near potential eight-thousander routes.[29] Technological innovations emerged as critical precursors during these attempts, particularly the experimental use of supplemental oxygen on Everest in the 1920s. The 1922 expedition introduced closed-circuit oxygen apparatus designed by J.S. Haldane, allowing climbers like George Finch and Geoffrey Bruce to reach 8,326 meters—higher than previous efforts without aid—though equipment failures and heavy weights limited its reliability.[30] Refined versions were tested in 1924, with Mallory and others using open-circuit sets, but malfunctions contributed to the expedition's overall failure, prompting debates on oxygen's ethical and practical role in "fair" ascents.[30] Among the era's key failures was the 1939 German-American K2 expedition led by Fritz Wiessner, which approached via the Northeast Ridge and established advanced camps despite logistical strains. On July 24, Wiessner and Pasang Kikuli reached 8,380 meters but turned back at approximately 8,400 meters due to sudden deteriorating weather, high winds, and fatigue, narrowly averting disaster; subsequent descent chaos claimed four lives from exhaustion and falls.[31] This close call illustrated the razor-thin margins on K2, where environmental unpredictability often overwhelmed even seasoned teams.First Ascents Timeline