Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Elvas

View on WikipediaYou can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Portuguese. (October 2012) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Key Information

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Walls and fortifications of Elvas | |

| Official name | Garrison Border Town of Elvas and its Fortifications |

| Location | Elvas, Portalegre District, Alentejo, Portugal |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iv) |

| Reference | 1367bis |

| Inscription | 2012 (36th Session) |

| Extensions | 2013 |

| Area | 179.356 ha (443.20 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 690 ha (1,700 acres) |

| Coordinates | 38°52′50.23″N 7°9′47.96″W / 38.8806194°N 7.1633222°W |

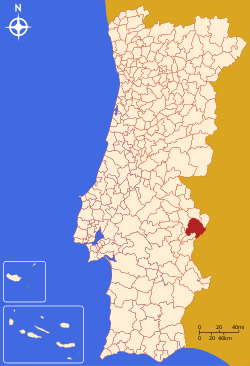

Elvas (Portuguese pronunciation: [ˈɛlvɐʃ] ⓘ), officially the City of Elvas (Portuguese: Cidade de Elvas), is a Portuguese municipality, former episcopal city and frontier fortress of easternmost central Portugal, located in the district of Portalegre in Alentejo. It is situated about 200 kilometres (120 mi) east of Lisbon, and about 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) west of the Spanish fortress of Badajoz, by the Madrid-Badajoz-Lisbon railway. The municipality population as of 2011[update] was 23,078,[1] in an area of 631.29 square kilometres (243.74 sq mi).[2] The city itself had a population of 16,640 as of 2011[update].[3]

Elvas is among the finest examples of intensive usage of the trace italienne (star fort) in military architecture, and has been a World Heritage Site since 30 June 2012. The inscribed site name is Garrison Border Town of Elvas and its Fortifications.

History

[edit]Elvas lies on a hill 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) northwest of the Guadiana river. The Amoreira Aqueduct, 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) long, supplies the city with clean water; it was begun early in the 15th century and completed in 1622. For some distance it includes four tiers of superimposed arches, with a total height of 40 metres (130 ft).[4]

The city was wrested from the Moors by Afonso I of Portugal in 1166 but was temporarily recaptured before its final occupation by the Portuguese in 1226. In 1570 it became an episcopal see, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Elvas, until 1818. The late Gothic Our Lady of the Assumption Cathedral, which has many traces of Moorish influence in its architecture, dates from the reign of Manuel I of Portugal (1495–1521).[4]

It was defended by seven bastions and the two forts of Santa Luzia and the Nossa Senhora da Graça Fort.[4] From 1642 it was the chief frontier fortress south of the Tagus, which withstood sieges by the Spanish in 1659, 1711, and 1801.[5] Elvas was the site of the Battle of the Lines of Elvas in 1659, during which the garrison and citizens of the city assisted in the rout of a Spanish Army.[citation needed] The Napoleonic French under Marshal Junot took it in March 1808 during the Peninsular War, but evacuated it in August after the conclusion of the Convention of Sintra.[5] The fortress of Campo Maior 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) to the northeast is known for its Napoleonic era siege by the French and relief by the British under Marshal Beresford in 1811, an exploit commemorated in a ballad by Sir Walter Scott.[4]

UNESCO site

[edit]The Garrison Border Town of Elvas and its Fortifications were added to the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 2012.[6]

The site, extensively fortified from the 17th to 19th centuries, represents the largest bulwarked dry ditch system in the world. Within its walls, the town contains barracks and other military buildings as well as churches and monasteries. While Elvas contains remains dating back to the 10th century, its fortification began during the Portuguese Restoration War. The fortifications played a major role in the Battle of the Lines of Elvas in 1659. The fortifications were designed by Dutch Jesuit Padre João Piscásio Cosmander and represent the best surviving example of the Dutch school of fortifications anywhere. The site consists the following:

- Amoreira Aqueduct, built to withstand long sieges.

- Historic Centre

- Fort of Santa Luzia and the covered way

- Nossa Senhora da Graça Fort

- Fortlet of São Mamede

- Fortlet of São Pedro

- Fortlet of São Domingos

Climate

[edit]Elvas has a hot summer mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csa) with mild winters, although occasionally temperatures may drop below 0 °C (32 °F) and very hot, dry summers, where temperatures occasionally exceed 40 °C (104 °F). Elvas climate is quite similar to that of Badajoz, being slightly cooler and more humid due to its higher altitude and greater influence from the Atlantic Ocean.[7] Precipitation varies from 500 to 600 mm (20 to 24 in) throughout the year, with an average of about 534 mm (21.0 in) annually. It is one of the hottest cities in Portugal during the summer, with an average maximum temperature close to 35 °C (95 °F).

| Climate data for Elvas, (1991-2020 normals), extremes (1981-present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.6 (72.7) |

24.1 (75.4) |

30.8 (87.4) |

35.3 (95.5) |

39.4 (102.9) |

43.2 (109.8) |

45.8 (114.4) |

45.1 (113.2) |

43.5 (110.3) |

36.1 (97.0) |

29.2 (84.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

45.8 (114.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 13.9 (57.0) |

15.9 (60.6) |

19.2 (66.6) |

21.6 (70.9) |

26.0 (78.8) |

31.2 (88.2) |

34.8 (94.6) |

34.6 (94.3) |

30.1 (86.2) |

24.2 (75.6) |

17.9 (64.2) |

14.5 (58.1) |

23.7 (74.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.0 (48.2) |

10.3 (50.5) |

13.2 (55.8) |

15.2 (59.4) |

18.9 (66.0) |

23.1 (73.6) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.9 (78.6) |

22.7 (72.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

12.9 (55.2) |

9.9 (49.8) |

17.1 (62.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 4.1 (39.4) |

4.7 (40.5) |

7.1 (44.8) |

8.8 (47.8) |

11.8 (53.2) |

15.0 (59.0) |

16.8 (62.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

15.2 (59.4) |

12.3 (54.1) |

8.0 (46.4) |

5.3 (41.5) |

10.5 (50.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.0 (19.4) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

1.5 (34.7) |

6.0 (42.8) |

9.7 (49.5) |

8.0 (46.4) |

4.0 (39.2) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 56.7 (2.23) |

48.9 (1.93) |

54.2 (2.13) |

53.4 (2.10) |

41.6 (1.64) |

16.8 (0.66) |

1.9 (0.07) |

5.3 (0.21) |

24.6 (0.97) |

76.7 (3.02) |

81.0 (3.19) |

73.3 (2.89) |

534.4 (21.04) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 7.4 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 7.3 | 5.5 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 3.2 | 7.2 | 7.9 | 7.6 | 62.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 154.3 | 161.8 | 212.1 | 224.6 | 275.4 | 316.2 | 366.6 | 339.2 | 252.2 | 198.6 | 164.8 | 129.4 | 2,795.2 |

| Source: Instituto de Meteorologia (Sunshine 1971-2000)[8] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Vila Fernando, 1971-2000 normals and extremes, elevation: 360 m (1,180 ft) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.0 (68.0) |

22.6 (72.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

31.0 (87.8) |

34.5 (94.1) |

42.0 (107.6) |

42.5 (108.5) |

40.6 (105.1) |

41.2 (106.2) |

33.6 (92.5) |

26.5 (79.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

42.5 (108.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 12.2 (54.0) |

13.8 (56.8) |

16.7 (62.1) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.3 (72.1) |

27.8 (82.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.8 (89.2) |

28.1 (82.6) |

21.7 (71.1) |

16.3 (61.3) |

13.1 (55.6) |

21.2 (70.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.4 (47.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.7 (53.1) |

13.0 (55.4) |

16.2 (61.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.6 (74.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

12.2 (54.0) |

9.6 (49.3) |

15.6 (60.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 4.7 (40.5) |

5.6 (42.1) |

6.7 (44.1) |

7.7 (45.9) |

10.1 (50.2) |

13.3 (55.9) |

15.7 (60.3) |

15.5 (59.9) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

8.1 (46.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

10.0 (49.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −5.0 (23.0) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

2.0 (35.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

9.0 (48.2) |

8.0 (46.4) |

4.0 (39.2) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 64.3 (2.53) |

54.6 (2.15) |

41.7 (1.64) |

54.0 (2.13) |

39.2 (1.54) |

23.2 (0.91) |

7.6 (0.30) |

4.5 (0.18) |

23.8 (0.94) |

58.6 (2.31) |

72.9 (2.87) |

88.2 (3.47) |

532.6 (20.97) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 11.0 | 9.2 | 7.6 | 9.1 | 7.1 | 4.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 3.9 | 8.2 | 9.3 | 10.1 | 82 |

| Source: Instituto de Meteorologia[9] | |||||||||||||

Civil parishes

[edit]Administratively, the municipality is divided in seven civil parishes (freguesias):[10]

- Assunção, Ajuda, Salvador e Santo Ildefonso

- Barbacena e Vila Fernando

- Caia, São Pedro e Alcáçova

- Santa Eulália

- São Brás e São Lourenço

- São Vicente e Ventosa

- Terrugem e Vila Boim

Notable people

[edit]

- Manuel Rodrigues Coelho (ca. 1555 – 1635) a Portuguese organist and composer.

- João de Fontes Pereira de Melo (1780–1856) a politician, a general and twice colonial governor of Cape Verde

- José Travassos Valdez, 1st Count of Bonfim (1787–1862) a Portuguese soldier and statesman.

- Fortunato José Barreiros (1797–1885) a colonial governor of Cape Verde and military architect.

- Adelaide Cabete (1867–1935) a Portuguese feminist and republican.

- Virgínia Quaresma (1882–1973) an early radical, feminist, lesbian journalist

- Sofia Pomba Guerra (1906–1976) a feminist, opponent of the Estado Novo government in Portugal and an activist in the anti-colonial movements of Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau.

- José António Rondão Almeida (born 1945) a Portuguese politician & Mayor of Elvas

- Toni Vidigal (born 1975), Jorge Vidigal (born 1978) & André Vidigal (born 1998) Angolan football brothers

- Raquel Guerra (born 1985) a Portuguese singer and actress.[11]

- Henrique Sereno (born 1985) a Portuguese former footballer with 236 club caps

Sister cities

[edit] Badajoz, Extremadura, Spain

Badajoz, Extremadura, Spain- Olivença, Disputed

Campo Maior, Alentejo, Portugal

Campo Maior, Alentejo, Portugal

References

[edit]- ^ Instituto Nacional de Estatística

- ^ "Áreas das freguesias, concelhos, distritos e país". Archived from the original on 2018-11-05. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ UMA POPULAÇÃO QUE SE URBANIZA, Uma avaliação recente – Cidades, 2004 Archived October 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Nuno Pires Soares, Instituto Geográfico Português (Geographic Institute of Portugal)

- ^ a b c d Chisholm 1911, p. 300.

- ^ a b Chisholm 1911, p. 301.

- ^ "Garrison Border Town of Elvas and its Fortifications".

- ^ "Climate normals 1991-2020". Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera. Retrieved 24 May 2025.

- ^ "Monthly Averages for Elvas (1991–2020)" (PDF). IPMA.

- ^ "Monthly Averages for Vila Fernando (1971–2000)" (PDF). IPMA.

- ^ Diário da República. "Law nr. 11-A/2013, page 552 44" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ Raquel Guerra, IMDb Database retrieved 16 July 2021.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Elvas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 300–301.

External links

[edit]Elvas

View on GrokipediaGeography and Environment

Location and Borders

Elvas is a municipality in eastern Portugal, situated in the Alentejo region and part of the Portalegre District.[7] Its geographical coordinates are approximately 38.88° N latitude and 7.16° W longitude.[8] The city center lies about 210 kilometers east of Lisbon by road and roughly 8 kilometers west of Badajoz in Spain, positioning Elvas as a prominent frontier settlement guarding a major historical crossing between the capitals of Portugal and Spain.[9][10] The municipality spans an area of 631.2 square kilometers.[2] Administratively, it borders Arronches to the north, Campo Maior to the northeast, the Spanish municipalities of Olivença and Badajoz to the southeast, Monforte to the south, and Portalegre to the west.[11] Olivença remains a point of territorial dispute, with Portugal maintaining historical claims to the area despite its current administration under Spain.[7] This border configuration has historically underscored Elvas's strategic military significance along the Portugal-Spain frontier.[4]

Topography and Natural Features

Elvas occupies a prominent hilltop position at an elevation of approximately 258 meters above sea level, within the broader undulating plains of eastern Alentejo.[12] The local terrain transitions from the elevated urban core to surrounding low hills and expansive flatlands, providing strategic vantage points that influenced its historical fortifications.[4] These hills, such as those hosting outlying forts like Santa Luzia and Graça, integrate with the irregular topography to form a defensive landscape adapted to natural contours rather than imposed upon them.[4] The Guadiana River, approximately 8 kilometers southeast of the city, marks a key natural feature and contributes to the riverine character of the regional environment, serving as a partial border with Spain.[13] Beyond this, the area lacks dramatic geological formations, featuring instead sun-exposed arable plains typical of Alentejo's semi-arid steppe-like expanses, with minimal forest cover and occasional modest ridges extending westward toward ranges like Serra de Ossa.[14] This topography supports agriculture, including olive groves and cork oaks, but is primarily shaped by its role in border defense amid open, traversable countryside.[14]Climate

Elvas experiences a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen classification: Csa), characterized by mild, wet winters and hot, dry summers.[15] The annual mean temperature is 17.1 °C, with average highs reaching 23.6 °C and lows 10.5 °C. Precipitation totals 534.5 mm annually, concentrated primarily from October to March, while summers are arid with minimal rainfall.[16] Winters (December–February) are mild, with average highs of 13–16 °C and lows around 4–5 °C, though frost occurs on about 7.7 days per year, occasionally dipping below -5 °C as in February 2012. Summers (June–August) are hot, with average highs exceeding 34 °C in July and August, and over 100 days annually above 30 °C, including 44 days above 35 °C; lows rarely fall below 15 °C. The wet season features 62.6 rainy days (≥1 mm precipitation), peaking in November at 81 mm, while July averages just 1.9 mm.[16][17] The following table summarizes monthly climate normals (1991–2020) from the Portuguese Institute for Sea and Atmosphere (IPMA) station at Elvas:| Month | Mean Temp (°C) | Max Temp (°C) | Min Temp (°C) | Precip (mm) | Rainy Days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 9.0 | 13.9 | 4.1 | 56.7 | 7.4 |

| February | 10.3 | 15.9 | 4.7 | 48.9 | 6.3 |

| March | 13.2 | 19.2 | 7.1 | 54.2 | 7.0 |

| April | 15.2 | 21.6 | 8.8 | 53.4 | 7.3 |

| May | 18.9 | 26.0 | 11.8 | 41.6 | 5.5 |

| June | 23.1 | 31.2 | 15.0 | 16.8 | 1.9 |

| July | 25.8 | 34.8 | 16.8 | 1.9 | 0.5 |

| August | 25.9 | 34.6 | 17.1 | 5.3 | 0.9 |

| September | 22.7 | 30.1 | 15.2 | 24.6 | 3.2 |

| October | 18.2 | 24.2 | 12.3 | 76.7 | 7.2 |

| November | 12.9 | 17.9 | 8.0 | 81.0 | 7.9 |

| December | 9.9 | 14.5 | 5.3 | 73.3 | 7.6 |

| Annual | 17.1 | 23.6 | 10.5 | 534.5 | 62.6 |

History

Ancient and Roman Foundations

The territory encompassing modern Elvas, located in the Alto Alentejo region of what was ancient Lusitania, exhibits evidence of prehistoric human activity, with archaeological traces suggesting intermittent settlement patterns influenced by local resources and topography. Iron Age hillforts, known as castros, such as the Castro de Segóvia in the Elvas municipality, represent proto-urban defenses typical of pre-Roman Iberian cultures, likely occupied by Lusitanian tribes who resisted external incursions through fortified positions on elevated terrain.[18] These settlements, characterized by circular stone structures and strategic hilltop locations, underscore a semi-nomadic warrior society adapted to the Iberian interior's agrarian and pastoral economy prior to Hellenistic and Roman influences.[18] Roman expansion into Lusitania accelerated during the late Republic, with Julius Caesar's campaigns subduing resistant Lusitanian groups around 60 BCE, followed by Augustus's administrative reorganization into the province of Lusitania circa 27 BCE.[19] This conquest integrated the Elvas area into Roman networks, evidenced by rural villas and infrastructure that facilitated agricultural exploitation and military control along frontier zones. Geophysical surveys at sites like Monte da Nora (Terrugem), within Elvas municipality, reveal Roman-era material culture, including pottery and structural remains indicative of romanization processes, where indigenous practices blended with imported technologies for land management and trade.[20] Such findings highlight a gradual shift from tribal autonomy to imperial oversight, though no major urban center like Emerita Augusta (Mérida) developed directly at Elvas, which remained peripheral to principal Roman hubs. Key remnants of Roman engineering persist in the landscape, notably the foundations underpinning later aqueducts in Elvas, which channeled water resources vital for settlement sustainability in the arid Alentejo.[21] These structures, adapted and expanded in subsequent eras, reflect Rome's emphasis on hydraulic infrastructure to support villas and waystations, with ceramic and epigraphic evidence from nearby surveys confirming sustained occupation into the late Empire.[22] The transition from Roman rule, marked by provincial stability until the 5th century CE, laid infrastructural precedents that influenced medieval reconfiguration of the site amid Visigothic and subsequent migrations.[23]Medieval Period and Reconquista

During the early medieval period, Elvas, referred to as Yalbash by Muslim rulers, served as a strategic frontier settlement in the Taifa of Badajoz within Al-Andalus, fortified against Christian incursions from the emerging County of Portugal.[24] Following the Umayyad conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in the 8th century, the town developed under Islamic administration, featuring a citadel and walls that underscored its role in defending the Guadiana River valley.[25] Archaeological evidence indicates continuity of Roman-era structures adapted for Moorish defense, with the population including Berber and Arab settlers alongside local Hispano-Roman converts.[26] The town's involvement in the Reconquista intensified in the mid-12th century amid Portugal's expansion under Afonso I (r. 1139–1185). In 1166, Christian forces, including allies of the Portuguese king such as the adventurer Geraldo Sem Pavor, briefly captured Elvas from Moorish control as part of campaigns targeting nearby strongholds like Juromenha and Évora.[25] [5] However, the Moors under the Almohad Caliphate swiftly retook it, exploiting internal divisions among Christian factions and the fragility of early conquests in the Alentejo region.[27] This back-and-forth reflected the broader volatility of the frontier, where Elvas changed hands multiple times between 1166 and the 1220s, often contested not only by Muslims but also by rival Christian kingdoms like León.[28] Definitive Portuguese incorporation occurred in 1229 under King Sancho II (r. 1223–1248), who reconquered Elvas from residual Moorish garrisons weakened by the Almohad collapse after the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212.[26] [5] Sancho II granted the town a foral charter that year, formalizing its status and encouraging settlement with privileges for repopulation, which solidified its role as a bulwark in Portugal's eastern border defenses during the final phases of the Reconquista.[27] [28] Post-conquest, medieval fortifications were expanded, including enhancements to the castle—originally Moorish but rebuilt in Romanesque style—comprising seven towers and encircling walls that protected against both Islamic remnants and Castilian encroachments.[25] Elvas thus transitioned from a contested outpost to a key node in Portugal's territorial consolidation, facilitating further advances into the Algarve by the 1240s and marking the effective end of Moorish presence in the Alentejo.[5]Early Modern Fortifications and Wars of Independence

Following the outbreak of the Portuguese Restoration War in 1640, which aimed to restore national independence after 60 years under Spanish Habsburg rule, Elvas assumed paramount strategic importance as a border garrison town controlling access between Lisbon and Madrid.[4] Its fortifications were urgently expanded to counter Spanish incursions, with major works beginning in 1643 under the direction of Dutch Jesuit engineer Cosmander, drawing on the geometric principles of Samuel Marolois and the bastioned trace of the Dutch school of military architecture.[4] These enhancements transformed Elvas into an irregular polygonal system encompassing twelve outlying forts around the medieval castle, featuring extensive dry moats and ramparts that constituted the largest such bulwarked dry-ditch ensemble globally.[4] The Amoreira Aqueduct, initiated in the late 16th century and completed in the early 17th, proved vital by ensuring water supply during prolonged sieges, enabling the garrison to sustain defensive operations independently.[4] In 1644, Elvas withstood a nine-day Spanish siege commanded by the Marquis of Torrecusa, where a garrison of approximately 2,000 Portuguese defenders repelled an assault by 14,000 Spanish troops, demonstrating the efficacy of the nascent fortifications.[29] This early success underscored Elvas's role as the "key to the kingdom," deterring further immediate threats and buying time for broader fortification projects.[5] A pivotal engagement occurred on 14 January 1659 in the Battle of the Lines of Elvas, where Portuguese forces under the command of Matias de Albuquerque decisively defeated a Spanish army led by Don Luis de Haro, preventing an advance on Lisbon and bolstering Portuguese morale in the protracted conflict.[30] The battle highlighted the defensive lines' tactical advantages, including entrenched positions and artillery placements that inflicted heavy casualties on the attackers.[31] Forts such as Santa Luzia, constructed amid the war, further reinforced the perimeter, repeatedly proving resilient against bombardment and assaults during the 1658-1659 campaign.[32] These developments during the Restoration War (1640-1668) not only secured Elvas as an impregnable bulwark but also exemplified early modern adaptations in trace italienne fortification to the Portuguese-Spanish frontier, influencing subsequent 18th-century enhancements while cementing the town's military legacy.[4] The war's conclusion with the Treaty of Lisbon in 1668 affirmed Portugal's sovereignty, with Elvas's unbreached defenses contributing significantly to the diplomatic leverage that ended hostilities.[4]19th Century to Present

In the early 19th century, Elvas was occupied by French forces as part of Napoleon's invasion of Portugal in November 1807, which initiated the Peninsular War; the town was later liberated by Anglo-Portuguese armies under the Duke of Wellington by 1814.[33] The fortifications underwent further modifications during this period, including adaptations to counter advancing artillery technologies.[34] During the Portuguese Liberal Wars (1828–1834), a civil conflict between constitutional liberals and absolutist Miguelists, Elvas functioned as a key border garrison; in 1834, Spanish liberal expeditionary forces under General José Ramón Rodil entered the town to bolster the constitutionalist side against Miguelist holdouts.[35] The conflict's resolution with liberal victory at the Concession of Evoramonte cemented Portugal's constitutional monarchy, though Elvas saw no major sieges thereafter.[35] The latter 19th century marked the peak and gradual obsolescence of Elvas's bulwark system, with final engineering adjustments to the dry-ditch defenses amid declining relevance against rifled guns and field artillery.[4] As a frontier outpost, the town hosted Portuguese garrisons through the First Republic (1910–1926) and the authoritarian Estado Novo regime (1933–1974), but without significant combat roles due to Portugal's neutrality in the World Wars and stable Iberian borders.[4] The Carnation Revolution of April 25, 1974, ended the dictatorship nationwide, leading to decolonization and democratic reforms that reduced Elvas's active military footprint as border tensions eased under NATO and European integration.[4] Portugal's accession to the European Economic Community in 1986 further diminished strategic militarization.[4] In 2012, UNESCO inscribed the Garrison Border Town of Elvas and its Fortifications as a World Heritage Site (reference 1367), honoring it as the world's largest bulwarked dry-ditch system developed from the 17th to 19th centuries.[4] Preservation initiatives since then have emphasized restoration of structures like the Fort of Graça and urban core, boosting heritage tourism while integrating modern infrastructure without altering the site's integrity.[4] As of 2025, Elvas maintains a population of approximately 22,000, with its economy increasingly oriented toward cultural preservation and cross-border cooperation with Spain.[36]Military Fortifications and Strategic Role

Development of the Bulwark System

The bulwark system of Elvas, encompassing its bastioned fortifications, originated from medieval defensive walls but underwent significant transformation in the 17th century during the Portuguese Restoration War (1640–1668).[34] Following the restoration of Portuguese independence from Spain in 1640, Elvas, as a strategic border garrison town, became the first to receive permanent bulwarked defenses, with construction commencing in 1643 under the direction of Dutch military engineer and Jesuit priest Cosmander.[34] [32] Cosmander's design adhered to the "Old Dutch Method," drawing on the fortification theories of Samuel Marolois, featuring an irregular polygonal trace with 12 bastioned fronts, a continuous dry ditch averaging 20 meters wide and 8–10 meters deep, ravelins for additional protection, and a maximum radius of 965 meters.[34] [32] This system integrated earlier structures like the medieval castle and walls while expanding southward to enclose the growing urban area, incorporating advanced trace italienne elements to counter artillery threats.[34] Key components developed concurrently included the Fort of Santa Luzia, constructed between 1641 and 1648 as a rectangular bastioned fort with four bulwarks to guard the northern approach.[34] The fortifications proved effective in the Battle of the Lines of Elvas on January 14, 1659, where Spanish forces under Don Luis de Haro failed to breach the defenses despite a prolonged siege.[34] Enhancements continued into the 18th century, with the Fort of Nossa Senhora da Graça initiated in 1763 under the influence of the Count of Lippe, evolving into a star-shaped stronghold with three lines of defense, completed by 1792 under engineers Étienne Macaux and Guillaume Louis Antoine de Valleré.[34] [37] In the early 19th century, amid Napoleonic threats, four smaller fortlets—São Mamede, São Pedro, São Domingos, and another—were erected around 1800 to extend the perimeter.[34] By the mid-19th century, advances in artillery rendered parts obsolete, leading to decommissioning by 1857, though the system remains the world's largest intact bulwarked dry-ditch fortification ensemble.[34]Key Structures and Engineering

The bulwarked fortifications of Elvas encompass a dry-ditch system with battered bulwarks, counterscarp galleries, and protruding ravelins designed to optimize enfilading fire and deter breaches, forming the world's largest intact example of such 17th- to 19th-century engineering.[34] This trace italienne layout, influenced by Dutch and French military theorists, integrated the urban walls with detached forts via covered ways, enabling coordinated artillery coverage over the Iberian border terrain.[38] The system's earthen ramparts and vaulted casemates supported heavy cannon, with glacis slopes engineered to expose attackers to raking fire while minimizing dead zones.[32] The Fort of Santa Luzia, erected in the 1640s during the Portuguese Restoration War, exemplifies early bastion design with its compact star-shaped plan and zigzag traverses, predating similar innovations by engineers like Blaise François Pagan and allowing defenders to interlock fields of fire across adjacent faces.[38] Spanning roughly 1.4 kilometers south of the historic center, it connects via a fortified covered way to the town's bastioned enceinte, incorporating pentagonal bastions and a surrounding ditch for mutual support against siege assaults.[32] Further north, the Fort of Nossa Senhora da Graça (also known as Forte da Graça), constructed from 1763 to 1792 under orders of King José I, features a robust square layout measuring 145 to 150 meters per side, augmented by four pentagonal bastions, ravelin-covered curtains, and three concentric lines of defense separated by deep dry moats on massive earthworks. Its Vauban-inspired architecture prioritized geometric precision for artillery dominance, with vaulted barracks and redoubts enabling sustained garrison operations independent of the main town. Supporting these defenses, the Amoreira Aqueduct extends over 7 kilometers from the Amoreira spring, comprising four tiers of semi-circular masonry arches up to 30 meters high, engineered with robust buttresses to withstand seismic activity and deliver 400 liters per second of water for troops and civilians.[39] Initiated around 1498 and completed by 1622 after intermittent construction involving over 6,000 laborers, its hydraulic gradient and siphon-like sections demonstrate advanced Renaissance civil engineering tailored to a fortified frontier.[40]Defensive Achievements and Battles

The fortifications of Elvas demonstrated resilience during medieval conflicts, notably withstanding a prolonged siege from 1325 to 1327 by forces under Alfonso XI of Castile amid border disputes with Portugal under Afonso IV.[41] A subsequent two-day siege in 1334 also failed to breach the defenses, underscoring the castle's early strategic value in repelling Castilian incursions.[41] Elvas' bulwark system, developed after Portugal's 1640 restoration of independence, proved pivotal in the Portuguese Restoration War against Spain. In 1644, the town endured a nine-day siege by Spanish troops, maintaining control and preventing a breakthrough into Alentejo.[30] The defenses reached their zenith in the Battle of the Lines of Elvas on January 13–14, 1659, where Portuguese forces, leveraging the entrenched lines and Fort of Nossa Senhora da Graça, repelled a major Spanish offensive.[30] In the 1659 engagement, Spanish commander Luís de Haro advanced approximately 14,500 troops (11,000 infantry and 3,500 cavalry) toward Lisbon, establishing positions near Elvas' outer lines.[30] Portuguese defenders, totaling around 11,000 from the Elvas garrison (including 5,000 regular infantry and 6,000 militia), coordinated with reinforcements from Estremoz to launch a dawn assault on January 13, shattering Spanish formations adjacent to the Graça fort and repulsing cavalry countercharges.[30] The battle concluded with a Spanish retreat by afternoon, yielding heavy losses: about 2,500 Spanish dead and 4,000 prisoners, against Portuguese casualties of roughly 200 killed and 600 wounded.[30] This victory halted Spanish invasion momentum, preserved Portuguese sovereignty, and highlighted the efficacy of Elvas' integrated fortification network in field battles.[30] During the Peninsular War, Elvas served as a key Allied stronghold, briefly occupied by French forces in 1807 before Portuguese and British troops recaptured it in 1808 via siege, enabling operations against Napoleonic invaders in the region.[42] The town's defenses, including outlying forts like Santa Luzia, supported logistics and repelled probes, contributing to the broader containment of French advances near Badajoz.[43]UNESCO World Heritage Status

Criteria and Inscription Process

The Garrison Border Town of Elvas and its Fortifications was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List under criterion (iv), which recognizes properties as outstanding examples of a type of building, architectural or technological ensemble, or landscape that illustrates significant stage(s) in human history.[44] The justification centers on Elvas representing the largest surviving bulwarked dry-ditch fortification system in the world, developed primarily from the 17th to 19th centuries, which exemplifies the evolution of European military architecture—particularly the "Old Dutch" system—and the strategic responses of emerging nation-states to threats of territorial conquest during periods like Portugal's War of Restoration (1640–1668).[44] [34] This ensemble, including the historic center, Amoreira Aqueduct, Fort of Graça, Fort of Santa Luzia, and associated fortlets, demonstrates intact integrity in conveying its defensive function, with authenticity supported by original plans, materials, and minimal post-19th-century alterations, though vulnerabilities such as vegetation overgrowth and modern encroachments were noted.[44] Comparative analysis by ICOMOS confirmed Elvas's superiority over other European examples like Valletta or Naarden in scale and preservation as an inland bulwark system.[34] The inscription process began with Portugal's nomination of the site in early 2011 as part of its obligations under the 1972 World Heritage Convention.[4] ICOMOS, UNESCO's advisory body for cultural properties, conducted an evaluation, assessing the nomination dossier for outstanding universal value, integrity, authenticity, protection, and management; it recommended inscription under criterion (iv) while referring the proposal back to Portugal for enhancements, including formal designation as a National Monument under Law No. 107/2001, expansion of protection zones, and implementation of an integrated management plan to address threats like vandalism and urban development.[34] The World Heritage Committee, at its 36th session held in Saint-Petersburg, Russia, from June 24 to July 6, 2012, reviewed the evaluation and inscribed the property on July 1, 2012, with an area of 179.3559 hectares and a buffer zone of 690 hectares encompassing seven key components.[44] [4] The decision emphasized the site's role in illustrating the consolidation of Portuguese independence and required ongoing measures such as funding for conservation, an inventory of features, and design guidelines to mitigate risks.[44] A minor boundary modification was approved in 2013 to refine the buffer zone.[45]Scope of the Site and Preservation Efforts

The Garrison Border Town of Elvas and its Fortifications encompasses a core property area of 179.3559 hectares, designated under UNESCO criterion (iv) for exemplifying an outstanding fortified garrison town with the world's largest bulwarked dry-ditch system.[4] The inscribed components include seven discrete elements: the Historic Centre (125.4311 ha), Amoreira Aqueduct (0.8148 ha), Fort of Santa Luzia with its connecting covered way (19.7116 ha), Fort of Graça (11.2544 ha), Fortlet of São Mamede (7.9608 ha), Fortlet of São Pedro (1.9843 ha), and Fortlet of São Domingos (12.1989 ha).[46] These form an irregular polygonal boundary centered on the medieval castle, integrating 12 forts across a hilly landscape to enclose the urban core and outer defenses, with a buffer zone of 690 hectares to safeguard visual and functional integrity against encroaching development.[4] A minor boundary modification was approved in 2013 to refine protections.[4] Preservation is coordinated through the Integrated Management Plan for the Fortifications of Elvas (IMPFE), established post-inscription to foster stakeholder collaboration, including the Municipality of Elvas, the Ministry of Culture via IGESPAR (now Directorate-General for Cultural Heritage), and private entities.[44] The site was classified as a National Monument under Portuguese Law No. 107/2001, with the buffer zone integrated into the Municipal Master Plan as a Special Protection Area by 2012.[44] Key efforts address vulnerabilities such as vegetation overgrowth, vandalism in unoccupied structures like the Fort of Graça, and threats from modern infrastructure; these include comprehensive inventories of defensive features, design guidelines for infill construction, and adaptive reuse projects to secure funding and prevent squatting.[44] The Fort of Graça, for instance, underwent rehabilitation between 2010 and 2016 under the World Monuments Fund, transforming it into a visitor-accessible interpretive center while preserving its earthen ramparts and star-shaped bastions. Ongoing monitoring emphasizes buffer zone enlargement, public education on heritage value, and cross-border cooperation with adjacent Spanish sites like Badajoz to mitigate shared risks from tourism and urbanization.[44] UNESCO's 2012 inscription decision urged sustained financial commitments and regular reporting to maintain authenticity, with original 17th-19th century materials and layouts largely intact despite localized impacts from communication masts and urban expansion.[44] These measures ensure the site's role as a testament to Vaubanian-influenced military engineering remains viable amid contemporary pressures.[4]Demographics and Society

Population Trends and Composition

The population of Elvas municipality has declined steadily in recent decades, reflecting broader demographic challenges in Portugal's Alentejo region, such as rural exodus and low birth rates. The 2021 census recorded 20,730 residents, a decrease from 23,078 in the 2011 census, equating to an annual change of -1.1%. By 2022, the figure was 20,398, with an average annual variation of -0.89% between 2018 and 2022. Estimates for 2024 suggest further reduction to 20,325, amid a low population density of approximately 32.4 inhabitants per km² across the 631 km² municipality.[47][48] Demographically, Elvas exhibits an aging structure typical of depopulating inland Portuguese municipalities, with an average age of 45.4 years in 2022. Gender distribution shows a slight female majority at 52.4%, compared to 47.6% males. The proportion of elderly residents (65+) is notably high in several parishes, such as Caia e São Pedro and Alcáçova, contributing to the overall aging trend. Foreign-born or foreign-nationality residents comprise a small 3.1% of the population, primarily from neighboring Spain or other EU countries, with the vast majority being ethnic Portuguese of longstanding local ancestry.[48][49]Social Structure and Migration Patterns

Elvas exhibits a social structure marked by an aging population and a shift toward smaller household units, reflecting broader trends in rural Portuguese municipalities. In 2021, the municipality had 20,730 residents, with 47.6% male and 52.3% female, and an average age of 45.9 years, contributing to an elderly dependency ratio that rose by 4 percentage points from 2001 to 2021.[50] A small Roma minority resides primarily in two social housing estates managed by the Portuguese Institute for Housing and Urban Rehabilitation, facing challenges such as high school absenteeism and social exclusion, which local policies prioritize for integration.[51] [50] Family and household composition underscore a trend of fragmentation, with 28.2% of the 8,571 households classified as unipersonal in 2021, of which 51.3% (1,239) consisted of elderly individuals living alone, heightening vulnerability to isolation.[50] Larger families have declined sharply, from 4,282 households with three or more members in 1991 to 2,964 in 2021, indicative of falling fertility rates and changing norms favoring smaller units over extended kin structures traditional in Alentejo agrarian society.[50] Economic indicators reveal modest stratification, with purchasing power at 90.5% of the national average in 2019 and 1,264 recipients of social insertion income support (70 per 1,000 active residents) in 2021, pointing to a working-class base supplemented by military heritage families and limited professional elites.[50] Migration patterns have driven demographic contraction, with the population falling 11.3% between 2001 and 2021, exacerbated by negative net migration saldo in both 2011 and 2021 alongside low birth rates and elevated mortality.[50] Youth out-migration to urban centers like Lisbon or abroad contributes to this depopulation, consistent with Alentejo-wide emigration flows historically tied to agricultural decline and limited opportunities, though recent national immigration upticks have yielded minimal impact in Elvas, where foreigners comprise just 3.1% of residents.[50] [48] As a border municipality, cross-border ties with Spain facilitate some seasonal or familial mobility, but overall inflows remain low, with 3.4% immigrant share noted in frontier studies, underscoring persistent net loss.[52]Economy

Historical Economic Foundations

Elvas's historical economic foundations rested on agrarian production characteristic of the Alentejo region, where large latifundia estates dominated, yielding cereals, olives, cork, and livestock to support local needs and rudimentary trade networks.[53] These activities provided the primary revenue for rural inhabitants, with the fertile plains around the town enabling self-sufficiency amid frequent border instability.[54] The town's role as a key Portuguese frontier stronghold infused its economy with military-driven impulses, particularly during the Restoration War (1640–1668) and subsequent fortifications era. Royal expenditures on defensive works from the 17th to 19th centuries, creating the world's largest bulwarked dry-ditch system, generated employment in construction, masonry, and engineering, drawing skilled labor and materials that circulated wealth locally.[4] Critical infrastructure like the Amoreira Aqueduct, initiated around 1498 under architects including Francisco de Arruda and completed in 1622 after extensions, stretched 7–8 kilometers with over 800 arches to deliver water from distant springs, bolstering population capacity, irrigation for crops, and siege endurance by sustaining the garrison.[55] [4] This hydraulic feat, funded by municipal and crown resources, indirectly amplified agricultural output and urban viability in an otherwise arid locale.[56] A resident garrison of soldiers and dependents further animated commerce, spurring provisioning markets for grain, meat, and textiles, while limited cross-border exchanges with Spain—interrupted by conflicts but viable in peacetime—added to mercantile flows before 19th-century stabilization diminished such reliance.[57]Modern Sectors and Challenges

The economy of Elvas relies heavily on the tertiary sector, encompassing services, commerce, and public administration, which dominates local employment and value added. Tourism has emerged as a vital modern pillar, capitalizing on the city's UNESCO World Heritage fortifications and proximity to the Spanish border, attracting visitors for cultural and historical sites while fostering related activities like hospitality and guided tours. Cross-border trade and logistics with Badajoz, Spain, support commerce through facilities such as the Transfrontier Business Center in the industrial zone, facilitating export-oriented enterprises and regional exchange.[58][59][60] Agriculture remains integral, aligned with Alentejo's regional strengths in cork, olives, wine, and cereals, though on a smaller scale in Elvas due to its urban-rural mix; supplementary activities include food processing and emerging circular economy initiatives in biomass. Public sector roles in defense, education, and health contribute substantially to gross value added, mirroring Alentejo's EUR 1.6 billion from these areas in 2021. Infrastructure developments, such as the Sines-Elvas rail line, promise economic stimulus through construction jobs and improved connectivity, potentially enhancing freight and passenger flows by 2030.[61][62][63] Key challenges include acute demographic shrinkage, with Elvas's population falling 12% between 2011 and 2024, exacerbating labor shortages and an aging demographic structure marked by low fertility and youth emigration to urban centers. This interior location fosters economic stagnation, with limited innovation and entrepreneurship hindering diversification beyond services and agriculture, as noted in regional analyses. Border dynamics introduce competition from Spanish markets, while reliance on EU funds for projects underscores vulnerabilities to policy shifts and slow private investment. Unemployment aligns with Portugal's national rate of around 6% in 2025, but regional disparities in Alentejo amplify risks of underemployment in low-productivity sectors.[64][65][66][67]Administration and Governance

Local Government Structure

The local government of Elvas operates within Portugal's municipal framework, established by the Constitution and Local Government Law (Lei n.º 75/2013, de 12 de setembro), featuring a dual structure of executive and deliberative organs. The Câmara Municipal serves as the executive body, responsible for implementing policies, managing municipal services such as urban planning, public works, education, and social support, and handling administrative tasks including licensing, fiscal oversight, and property management.[68] It comprises a president, elected directly by universal suffrage for a four-year term, and six vereadores (councillors), totaling seven members, with the president delegating portfolios to vereadores for specialized areas like finance, culture, and infrastructure.[69] The Assembleia Municipal functions as the deliberative body, overseeing the Câmara's actions, approving annual budgets, urban plans, and regulations, and authorizing major decisions such as loans or asset sales. It consists of 21 directly elected deputies plus the seven presidents of the freguesias (civil parishes), totaling 28 members, also serving four-year terms aligned with national local elections. The assembly elects its own president and secretaries, convenes in ordinary sessions multiple times annually, and can hold extraordinary meetings to address urgent matters.[70] Internal organization of the Câmara includes departments for administration, urbanism, human resources, and technical services, as outlined in its organigram and regulated by Decree-Law n.º 305/2009, de 23 de outubro, with recent reorganizations approved in 2022 to enhance efficiency in service delivery.[71] [72] Both organs emphasize transparency and accountability, with public access to meetings and decisions mandated by law, though practical implementation varies by administration. Elections occur every four years, with the most recent in October 2025 determining the current composition.[73]Civil Parishes and Territorial Division

The Municipality of Elvas, covering 631.29 square kilometers in the Portalegre District of Portugal's Alentejo region, is administratively divided into seven civil parishes (freguesias), a structure established by the 2013 territorial reform under Law No. 11-A/2013, which merged smaller former parishes to streamline local governance.[11][74] This division reflects the municipality's rural and frontier character, with parishes encompassing both urban core areas and dispersed agricultural settlements along the border with Spain's Badajoz Province to the east and south.[11] To the north and west, it borders other Portuguese municipalities including Campo Maior, Arronches, and Monforte, facilitating regional connectivity via the A6 motorway and rail links.[7] The civil parishes are:- União das Freguesias de Assunção, Ajuda, Salvador e Santo Ildefonso (encompassing the historic city center and its immediate fortifications)

- União das Freguesias de Barbacena e Vila Fernando

- União das Freguesias de Caia, São Pedro e Alcáçova

- Santa Eulália

- União das Freguesias de São Brás e São Lourenço

- União das Freguesias de São Vicente e Ventosa

- União das Freguesias de Terrugem e Vila Boim[11][75]

Culture and Heritage

Architectural and Cultural Monuments

The Garrison Border Town of Elvas and its Fortifications, inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2012, encompass the historic center, medieval castle, remnants of successive walled enclosures, and 17th- to 19th-century star-shaped forts, exemplifying advanced military architecture designed to defend Portugal's border against Spain.[4] These defenses, including the six-pointed 17th-century walls known as Muralhas Seiscentistas, integrate bastioned trace systems with detached forts like Forte de Santa Luzia (constructed 1640–1648) and Forte da Graça (built 1763–1792), featuring massive earthworks, deep ditches, and strategic hilltop positions for panoramic surveillance.[44] The Elvas Castle, originally an Islamic fortress from the 12th century and rebuilt in the 13th and 14th centuries under Portuguese rule, anchors the urban core with its robust towers and provides commanding views over the surrounding plains.[5] The Aqueduto da Amoreira, initiated in 1498 and completed in 1622 after overcoming engineering and funding delays, stretches over 7 kilometers with 843 arches, ranking among the Iberian Peninsula's longest aqueducts and ensuring water supply to withstand prolonged sieges.[55][76] Overseen initially by architect Francisco de Arruda, who also contributed to Lisbon's Belém Tower, its multi-tiered stone structure channels water from the Amoreira spring to a central fountain in Elvas, demonstrating Renaissance hydraulic ingenuity adapted for military resilience.[55] Religious and civil architecture within the historic center includes the Church of Nossa Senhora da Assunção, a Gothic-Manueline structure serving as the cathedral, and the Dominican Church, both reflecting medieval and Renaissance influences amid the fortified layout.[28] These monuments, alongside the Praça da República square framed by arcaded buildings, preserve Elvas's identity as a layered garrison town, where urban planning prioritized defensive functionality over aesthetic ornamentation.[5]Traditions and Local Identity

Elvas maintains a strong Catholic heritage, evident in its annual religious festivals that blend devotion with communal gatherings. The Festas em Honra do Senhor Jesus da Piedade, held from September 19 to 28, center on the sanctuary dedicated to this image of Christ, attracting pilgrims with processions such as the Procissão dos Pendões, which initiates the event and features banners carried through the streets.[77][78] These coincide with the Feira de São Mateus, established in 1574, incorporating fairs, music, and fireworks alongside liturgical observances.[79] Holy Week processions and Easter customs, including the consumption of folar da Páscoa and local "bolos fintos" (fried dough pastries), reinforce seasonal piety and family traditions typical of Alentejo.[80] Musical traditions underscore Elvas's cultural distinctiveness, particularly the ronca, a friction membranophone crafted from a clay vessel covered in animal skin and played with a stick soaked in resin. Originating from African influences via Portuguese explorations, the ronca accompanies Christmas carols dedicated to the Christ Child, with groups roaming neighborhoods in a custom preserved since at least the early 20th century.[81][82] Local artisans, such as those in the medieval castle workshops, continue producing these instruments, linking festive songs to the town's garrison past.[83] Gastronomic identity revolves around preserved fruits and hearty Alentejo fare, with ameixas de Elvas—Claudia plums candied in syrup or dried—representing a centuries-old craft formalized in production since 1919 at the Fábrica-Museu da Ameixa. These sweets, often paired with sericaia (a cinnamon-spiced custard cake), symbolize the region's agricultural resilience and conventual influences.[84][85] Broader cuisine includes migas com entrecosto (breadcrumb dish with ribs) and sopas de tomate, reflecting rural self-sufficiency amid the borderlands.[86] Folklore groups like the Rancho Folclórico de Elvas preserve dances and attire evoking agrarian roles—ceifeiros (reapers), mondadeiras (weeders)—fostering a sense of continuity in this frontier municipality.[87]Notable Individuals

Adelaide Cabete (25 January 1867 – 14 September 1935), born in Alcáçova near Elvas to a family of farm laborers, became Portugal's first female physician after overcoming barriers to education, qualifying in 1900 following marriage at age 18 and self-funded studies.[88] She advocated for women's suffrage, republicanism, and child welfare, founding organizations like the Republican Women's Center in 1909 and contributing essays on gender equality amid opposition from conservative institutions. Her work emphasized empirical needs for female literacy and health access, drawing from firsthand observations in rural Alentejo poverty. Manuel Rodrigues Coelho (c. 1555 – 1635), a native of Elvas who received early musical training at its cathedral, rose as one of Portugal's pioneering keyboard composers, publishing Flores de música in 1620 with versos and toccatas that advanced Iberian organ polyphony through structured variations and imitative techniques.[89] Serving as organist in Badajoz and later Lisbon Cathedral from 1603, his compositions reflect causal influences from Spanish vihuela traditions and local liturgical demands, preserving empirical keyboard pedagogy without undue romanticization.[90] João de Fontes Pereira de Melo (25 January 1780 – 28 October 1856), born in São Pedro, Elvas, pursued a military career reaching general rank while entering politics as a colonial administrator, governing Cape Verde twice (1823–1826 and 1832–1835) where he implemented fiscal reforms amid resource scarcity and slave trade transitions. His diplomatic efforts stabilized Portuguese holdings post-Napoleonic disruptions, prioritizing verifiable administrative efficiency over ideological overreach, though limited by era-specific communication delays.International Relations

Twin Towns and Partnerships

Elvas maintains twin town (geminação) agreements with select municipalities to foster cultural, economic, and historical exchanges. These partnerships emphasize shared heritage, particularly military and border-related histories.[91] The city formalized a twinning protocol with Viseu, Portugal, on 3 October 2022, highlighting mutual devotion to Saint Matthew as a unifying patron saint and promoting cooperation in areas such as education and tourism.[91][92] A geminação with Olivença, a territory historically linked to Portugal, was established on 20 May 1990, reflecting longstanding cultural and administrative ties despite ongoing territorial disputes with Spain.[93] In October 2024, Elvas signed a cooperation and friendship protocol with Bückeburg, Germany, commemorating the 18th-century contributions of Count Wilhelm Friedrich of Schaumburg-Lippe, who led Portuguese forces during the War of the Spanish Succession and influenced Elvas' fortifications. This agreement enables exchanges in economy, education, and culture.[94][95] Beyond formal twinnings, Elvas engages in broader partnerships through the Eurocidade Elvas-Badajoz-Campo Maior (EuroBEC), a transborder cooperation framework signed on 3 May 2018 with Badajoz, Spain, and Campo Maior, Portugal. This initiative focuses on integrated development in mobility, environment, and economic activities across the Portugal-Spain frontier, without constituting a traditional geminação.[96]| Twin Town | Country | Year Established | Key Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viseu | Portugal | 2022 | Cultural and religious ties, tourism |

| Olivença | Portugal (disputed) | 1990 | Historical and administrative links |

| Bückeburg | Germany | 2024 | Military heritage, education exchanges |

.jpg/250px-31202-Elvas_(48749062731).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-31202-Elvas_(48749062731).jpg)