Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lingual papillae

View on Wikipedia| Lingual papillae | |

|---|---|

Anatomic landmarks of the tongue. Filiform papillae cover most of the dorsal surface of the anterior 2/3 of the tongue, with fungiform interspaced. Just in front of the sulcus terminalis lies a V-shaped line of circumvallate papillae, and on the posterior aspects of the lateral margins of the tongue lie the foliate papillae. | |

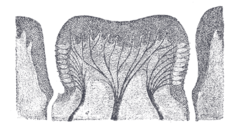

Semidiagrammatic view of a portion of the mucous membrane of the tongue. Two fungiform papillae are shown. On some of the filiform papillae the epithelial prolongations stand erect, in one they are spread out, and in three they are folded in. | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Tongue |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | papillae linguales |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_4102 |

| TA98 | A05.1.04.013 |

| TA2 | 2837 |

| TH | H3.04.01.0.03006 |

| FMA | 54819 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Lingual papillae (sg.: papilla, from Latin lingua 'tongue' and papilla 'nipple, teat') are small structures on the upper surface of the tongue that give it its characteristic rough texture. The four types of papillae on the human tongue have different structures and are accordingly classified as circumvallate (or vallate), fungiform, filiform, and foliate. All except the filiform papillae are associated with taste buds.[1]

Structure

[edit]In living subjects, lingual papillae are more readily seen when the tongue is dry.[2] There are four types of papillae present on the tongue in humans:

Filiform papillae

[edit]

Filiform papillae (from Latin filum 'thread' and fōrmis 'having the form of') are the most numerous of the lingual papillae.[1] They are fine, small, cone-shaped papillae found on the anterior surface of the tongue.[3] They are responsible for giving the tongue its texture and are responsible for the sensation of touch. Unlike the other kinds of papillae, filiform papillae do not contain taste buds.[1] They cover most of the front two-thirds of the tongue's surface.[2]

They appear as very small, conical or cylindrical surface projections,[2] and are arranged in rows which lie parallel to the sulcus terminalis. At the tip of the tongue, these rows become more transverse.[2]

Histologically, they are made up of irregular connective tissue cores with a keratin–containing epithelium which has fine secondary threads.[2] Heavy keratinization of filiform papillae, occurring for instance in cats, gives the tongue a roughness that is characteristic of these animals.

These papillae have a whitish tint, owing to the thickness and density of their epithelium. This epithelium has undergone a peculiar modification as the cells have become cone–like and elongated into dense, overlapping, brush-like threads. They also contain a number of elastic fibers, which render them firmer and more elastic than the other types of papillae. The larger and longer papillae of this group are sometimes termed papillae conicae.

Fungiform papillae

[edit]

The fungiform papillae (from Latin fungī 'mushroom' and fōrmis 'having the form of') are club shaped projections on the tongue, generally red in color. They are found on the tip of the tongue, scattered amongst the filiform papillae but are mostly present on the tip and sides of the tongue. They have taste buds on their upper surface which can distinguish the five tastes: sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and umami. They have a core of connective tissue. The fungiform papillae are innervated by the seventh cranial nerve, more specifically via the submandibular ganglion, chorda tympani, and geniculate ganglion ascending to the solitary nucleus in the brainstem.

Foliate papillae

[edit]

Foliate papillae (from Latin foliātus 'leafy') are short vertical folds and are present on each side of the tongue.[2] They are located on the sides at the back of the tongue, just in front of the palatoglossal arch of the fauces.[4][2] There are four or five vertical folds,[2] and their size and shape is variable.[4] The foliate papillae appear as a series of red colored, leaf–like ridges of mucosa.[2] They are covered with epithelium, lack keratin and so are softer, and bear many taste buds.[2] They are usually bilaterally symmetrical. Sometimes they appear small and inconspicuous, and at other times they are prominent. Because their location is a high risk site for oral cancer, and their tendency to occasionally swell, they may be mistaken as tumors or inflammatory disease. Taste buds, the receptors of the gustatory sense, are scattered over the mucous membrane of their surface. Serous glands drain into the folds and clean the taste buds. Lingual tonsils are found immediately behind the foliate papillae and, when hyperplastic, cause a prominence of the papillae.

Circumvallate papillae

[edit]

The circumvallate papillae (or vallate papillae, from Latin vallum 'wall') are dome-shaped structures on the human tongue that vary in number from 8 to 12. They are situated on the surface of the tongue immediately in front of the foramen cecum and sulcus terminalis, forming a row on either side; the two rows run backward and medially, and meet in the midline. Each papillae consists of a projection of mucous membrane from 1 to 2 mm. wide, attached to the bottom of a circular depression of the mucous membrane; the margin of the depression is elevated to form a wall (vallum), and between this and the papilla is a circular sulcus termed the fossa. The papilla is shaped like a truncated cone, the smaller end being directed downward and attached to the tongue, the broader part or base projecting a little above the surface of the tongue and being studded with numerous small secondary papillae and covered by stratified squamous epithelium. Ducts of lingual salivary glands, known as Von Ebner's glands empty a serous secretion into the base of the circular depression, which acts like a moat. The function of the secretion is presumed to flush materials from the base of circular depression to ensure that taste buds can respond to changing stimuli rapidly.[5] The circumvallate papillae get special afferent taste innervation from cranial nerve IX, the glossopharyngeal nerve, even though they are anterior to the sulcus terminalis. The rest of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue gets taste innervation from the chorda tympani of cranial nerve VII, distributed with the lingual nerve of cranial nerve V.

Function

[edit]Lingual papillae, particularly filiform papillae, are thought to increase the surface area of the tongue and to increase the area of contact and friction between the tongue and food.[2] This may increase the tongue's ability to manipulate a bolus of food, and also to position food between the teeth during mastication (chewing) and swallowing.

Clinical significance

[edit]Depapillation

[edit]In some diseases, there can be depapillation of the tongue, where the lingual papillae are lost, leaving a smooth, red and possibly sore area. Examples of depapillating oral conditions include geographic tongue, median rhomboid glossitis and other types of glossitis. The term glossitis, particularly atrophic glossitis is often used synonymously with depapillation. Where the entire dorsal surface of the tongue has lost its papillae, this is sometimes termed "bald tongue".[4] Nutritional deficiencies of iron, folic acid, and B vitamins may cause depapillation of the tongue.[4]

Papillitis/hypertrophy

[edit]Papillitis refers to inflammation of the papillae, and sometimes the term hypertrophy is used interchangeably.[citation needed]

In foliate papillitis the foliate papillae appear swollen. This may occur due to mechanical irritation, or as a reaction to an upper respiratory tract infection.[4] Other sources state that foliate papilitis refers to inflammation of the lingual tonsil, which is lymphoid tissue.[6]

Other animals

[edit]Seven types of papillae are described in domestic mammals, with their presence and distribution being species-specific:[7] -Mechanical papillae: filiform, conical, lentiform, marginal; -Taste papillae: fungiform, circumvallate, foliate

Foliate papillae are fairly rudimentary structures in humans,[1] representing evolutionary vestiges of similar structures in many other mammals.[2]

Additional images

[edit]-

The mouth. The cheeks have been slit transversely and the tongue pulled forward.

-

Papillae and other tongue landmarks

-

Foliate papillae

-

Floor of mouth. Deep dissection. Anterior view.

-

Floor of mouth. Deep dissection. Anterior view.

-

A picture showing filiform papillae taken using a USB microscope.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Norton N (2007). Netter's head and neck anatomy for dentistry. illustrations by Netter FH. Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders Elsevier. p. 402. ISBN 978-1929007882.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Susan Standring (editor in chief)] (2008). "Chapter 33: NECK AND UPPER AERODIGESTIVE TRACT". Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice (40th ed.). [Edinburgh]: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0443066849.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Tongue | Gastrointestinal Tract". histologyguide.com. Retrieved 2023-02-19.

- ^ a b c d e Scully C (2013). Oral and maxillofacial medicine : the basis of diagnosis and treatment (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 401, 402. ISBN 9780702049484.

- ^ Ross, H R; Pawlina, W (2011). Histology: A text and atlas. Baltimore, MD.: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-7200-6.

- ^ Rajendran A; Sundaram S (10 February 2014). Shafer's Textbook of Oral Pathology (7th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences APAC. p. 34. ISBN 978-81-312-3800-4.

- ^ König, Liebich (2020). Veterinary anatomy of domestic animals: textbook and colour atlas (7th, updated and extended ed.). Stuttgart ; New York: Georg Thieme Verlag. ISBN 978-3-13-242933-8.