Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Formation (association football)

View on Wikipedia

In association football, the formation of a team refers to the position players take in relation to each other on a pitch. As association football is a fluid and fast-moving game, a player's position (with the exception of the goalkeeper) in a formation does not define their role as tightly as that of rugby player, nor are there breaks in play where the players must line up in formation (as in gridiron football). A player's position in a formation typically defines whether a player has a mostly defensive or attacking role, and whether they tend to play centrally or towards one side of the pitch.

Formations are usually described by three or more numbers in order to denote how many players are in each row of the formation, from the most defensive to the most advanced. For example, the "4–5–1" formation has four defenders, five midfielders, and a single forward. The choice of formation is normally made by a team's manager or head coach. Different formations can be used depending on whether a team wishes to play more attacking or defensive football, and a team may switch formations between or during games for tactical reasons. Teams may also use different formations for attacking and defending phases of play in the same game.

In the early days of football, most team members would play in attacking roles, whereas modern formations are generally split more evenly between defenders, midfielders, and forwards.

Terminology

[edit]Formations are described by categorising the players (not including the goalkeeper) according to their positioning along (not across) the pitch, with the more defensive players given first. For example, 4–4–2 means four defenders, four midfielders, and two forwards.

Traditionally, those within the same category (for example the four midfielders in a 4–4–2) would generally play as a fairly flat line across the pitch, with those out wide often playing in a slightly more advanced position. In many modern formations, this is not the case, which has led to some analysts splitting the categories in two separate bands, leading to four- or even five-numbered formations. A common example is 4–2–1–3, where the midfielders are split into two defensive and one offensive player; as such, this formation can be considered a type of 4–3–3. An example of a five-numbered formation would be 4–1–2–1–2, where the midfield consists of a defensive midfielder, two central midfielders and an offensive midfielder; this is sometimes considered to be a kind of 4–4–2 (specifically a 4–4–2 diamond, referring to the lozenge shape formed by the four midfielders).

The numbering system was not present until the 4–2–4 system was developed in the 1950s.

Diagrams in this article use a "goal keeper at the bottom" convention but initially it was the opposite. The first numbering systems started with the number 1 for the goalkeeper (top of diagrams) and then defenders from left to right and then to the bottom with the forwards at the end.

Historical formations

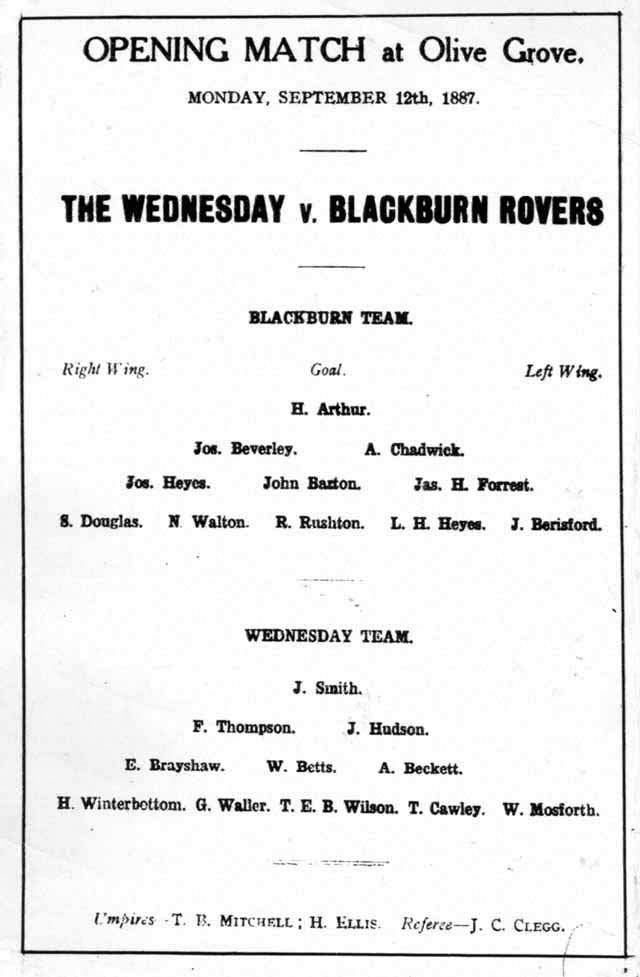

[edit]In the football matches of the 19th century, defensive football was not played, and the line-ups reflected the all-attacking nature of these games.

In the first international game, Scotland against England on 30 November 1872, England played with seven or eight forwards in a 1–1–8 or 1–2–7 formation, and Scotland with six, in a 2–2–6 formation. For England, one player would remain in defence, picking up loose balls, and one or two players would roam the midfield and kick the ball upfield for the other players to chase. The English style of play at the time was all about individual excellence and English players were renowned for their dribbling skills. Players would attempt to take the ball forward as far as possible and only when they could proceed no further, would they kick it ahead for someone else to chase. Scotland surprised England by actually passing the ball among players. The Scottish outfield players were organized into pairs and each player would always attempt to pass the ball to his assigned partner. Ironically, with so much attention given to attacking play, the game ended in a 0–0 draw.

Pyramid (2–3–5)

[edit]

The first long-term successful formation was recorded in 1880.[1] In Association Football, however, published by Caxton in 1960, the following appears in Vol II, page 432: "Wrexham ... the first winner of the Welsh Cup in 1877 ... for the first time certainly in Wales and probably in Britain, a team played three half-backs and five forwards ..."

The 2–3–5 was originally known as the "Pyramid",[2] with the numerical formation being referenced retrospectively. By the 1890s, it was the standard formation in England and had spread all over the world. With some variations, it was used by most top-level teams up to the 1930s.

For the first time, a balance between attacking and defending was reached. When defending, the halfback-trio were the first facing opposing forwards; when those were surpassed, then fullbacks met forwards as the last line of defence.

The centre halfback had a key role in both helping to organise the team's attack and marking the opponent's centre forward, supposedly one of their most dangerous players.

This formation was used by Uruguay to win the 1924 and 1928 Olympic Games and also the 1930 FIFA World Cup.

It was this formation which gave rise to the convention of shirt numbers increasing from the back and the right.[3]

Danubian school

[edit]The Danubian school of football is a modification of the 2–3–5 formation in which the centre forward plays in a more withdrawn position. As played by Austrian, Czechoslovak and Hungarian teams in the 1920s, it was taken to its peak by the Austrians in the 1930s. This school relied on short passing and individual skills, heavily influenced by the likes of Hugo Meisl and Jimmy Hogan, an English coach who visited Austria at the time.

Metodo (2–3–2–3)

[edit]

The metodo was devised by Vittorio Pozzo, coach of the Italy national team in the 1930s.[4] A derivation of the Danubian school, it can be called MM (if the goalkeeper is at the top of the diagram) or WW (if the goalkeeper is at the bottom). The system was based on the 2–3–5 formation; Pozzo realised that his half-backs would need some more support in order to be superior to the opponents' midfield, so he pulled two of the forwards to just in front of midfield, creating a 2–3–2–3 formation. This created a stronger defence than previous systems, as well as allowing effective counter-attacks. The Italy national team won back-to-back World Cups, in 1934 and 1938, using this system. It has been argued that Pep Guardiola's Barcelona and Bayern Munich used a modern version of this formation.[5] This formation is also similar to the standard in table football, featuring two defenders, five midfielders and three strikers (which cannot be altered as the "players" are mounted on axles).

WM

[edit]

The WM formation, named after the letters resembled by the positions of the players on its diagram, was created in the mid-1920s by Herbert Chapman of Arsenal to counter a change in the offside law in 1925. The change had reduced the number of opposition players that attackers needed between themselves and the goal-line from three to two. Chapman's formation included a centre-back to stop the opposing centre-forward (who otherwise could have taken greater advantage of the changed law), and tried to balance defensive and offensive playing. The formation became so successful that by the late 1930s most English clubs had adopted the WM. Retrospectively, the WM has either been described as a 3–2–5 or as a 3–4–3, or more precisely a 3–2–2–3, reflecting the letters which symbolise it. The gap in the centre of the formation between the two wing halves ( Half backs ) and the two inside forwards allowed Arsenal to counter-attack effectively. The WM was subsequently adopted by several English sides, but none could apply it in quite the same way Chapman had. This was mainly due to the comparative rarity of players like Alex James in the English game at that time. He was one of the earliest playmakers in the history of the game, and as a midfielder was the hub around which Chapman's Arsenal revolved. In 2016, new manager Patrick Vieira, a former Arsenal player, brought the WM formation to New York City FC.[6] In Italian football, the WM formation was known as the sistema, and its use in Italy later led to the development of the catenaccio formation.[7] The WM formation was used by West Germany during the 1954 FIFA World Cup.[8] It antedates Pozzo's Metodo and made more radical changes to the widely used system of that era: the 2–3–5 formation.

WW

[edit]

The WW formation (also known as the MM formation, according to the current diagram convention, that is goalkeeper at the bottom. However, it is called the WW formation if the goalkeeper is depicted at the top as was customary at the time), was a development on the WM formation. It was created by Hungarian Márton Bukovi, who turned the 3–2–2–3/WM formation into a 3–2–3–2 by effectively turning the forward "M" upside down (that is M to W).[9] The lack of an effective centre-forward in Bukovi's team necessitated moving a forward back to midfield to create a playmaker, with another midfielder instructed to focus on defence. This transformed into a 3–2–1–4 formation when attacking and turned back to 3–2–3–2 when possession is lost. This formation has been described by some as somewhat of a genetic link between the WM and 4–2–4 and was also successfully used by Bukovi's compatriot Gusztáv Sebes for the Hungarian Golden Team in the early 1950s.[9]

3–3–4

[edit]The 3–3–4 formation was similar to the WW, with the notable exception of having an inside-forward (as opposed to centre-forward) deployed as a midfield schemer alongside the two wing-halves. This formation was commonplace during the 1950s and early 1960s. One of the best exponents of the system was Tottenham Hotspur's double-winning side of 1961, which deployed a midfield of Danny Blanchflower, John White and Dave Mackay. Porto won the 2005–06 Primeira Liga using this unusual formation under manager Co Adriaanse. Recent sides which has also been argued to use this formation include Paris Saint-Germain under Luis Enrique and Arsenal under Mikel Arteta.

4–2–4

[edit]

The 4–2–4 formation attempts to combine a strong attack with a strong defence, and was conceived as a reaction to the WM's stiffness. It could also be considered a further development of the WW. The 4–2–4 was the first formation to be described using numbers.

While the initial developments leading to the 4–2–4 were devised by Márton Bukovi, the credit for creating the 4–2–4 lies with two people: Flávio Costa, the Brazilian national coach in the early 1950s, as well as another Hungarian, Béla Guttman. These tactics seemed to be developed independently, with the Brazilians discussing these ideas while the Hungarians seemed to be putting them into motion.[9][10][11] The fully developed 4–2–4 was only "perfected" in Brazil, however, in the late 1950s.

Costa published his ideas, the "diagonal system", in the Brazilian newspaper O Cruzeiro, using schematics and, for the first time, the formation description by numbers.[10] The "diagonal system" was another precursor of the 4–2–4 and was created to spur improvisation in players.

Guttmann himself moved to Brazil later in the 1950s to help develop these tactical ideas using the experience of Hungarian coaches.

The 4–2–4 formation made use of the players' increasing levels of skill and fitness, aiming to effectively use six defenders and six forwards, with the midfielders performing both tasks. The fourth defender increased the number of defensive players but mostly allowed them to be closer together, thus enabling effective cooperation among them, the point being that a stronger defence would allow an even stronger attack.

The relatively empty midfield relied on defenders that should now be able not only to steal the ball, but also hold it, pass it or even run with it and start an attack. So this formation required that all players, including defenders, are somehow skilful and with initiative, making it a perfect fit for the Brazilian players' minds. The 4–2–4 needed a high level of tactical awareness, as having only two midfielders could lead to defensive problems. The system was also fluid enough to allow the formation to change throughout play.

The 4–2–4 was first used with success at the club level in Brazil by Santos, and was used by Brazil in their wins at the 1958 World Cup and 1970 World Cups, both featuring Pelé, and Mário Zagallo, the latter of whom played in 1958 and coached in 1970. The then Indian football team manager, Syed Abdul Rahim introduced the classic 4–2–4 formation in Indian football team much before Brazil popularised it in the 1958 World Cup, which was also regarded as the golden era of Indian Football. The formation was quickly adopted throughout the world after the Brazilian success. Under the management of Jock Stein, Celtic won the 1966–67 European Cup and reached the final of the 1969–70 European Cup using this formation.

It was also used by Vladimír Mirka in Czechoslovakia's victorious 1968 UEFA European Under-18 Championship campaign. He continued to use it after its waning days.

Contemporary formations

[edit]The following formations are used in modern football. The formations are flexible allowing tailoring to the needs of a team, as well as to the players available. Variations of any given formation include changes in positioning of players, as well as replacement of a traditional defender by a sweeper.

4–4–2

[edit]

This formation was the most common in football in the 1990s and early 2000s, in which midfielders are required to work hard to support both the defence and the attack: typically one of the central midfielders is expected to go upfield as often as possible to support the forward pair, while the other will play a "holding role", shielding the defence; the two wide midfield players must move up the flanks to the goal line in attacks and yet also protect the full-backs.[12][13] On the European level, the major example of a team using a 4–4–2 formation was Milan, trained by Arrigo Sacchi and later Fabio Capello, which won three European Cups, two Intercontinental Cups, and three UEFA Super Cups between 1988 and 1995.

More recently, commentators have noted that at the highest level, the 4–4–2 is being phased out in favour of formations such as the 4–2–3–1.[14] In 2010, none of the winners of the Spanish, English and Italian leagues, nor the Champions League, relied on the 4–4–2. Following England's elimination at the 2010 World Cup by a 4–2–3–1 Germany side, England national team coach Fabio Capello (who was notably successful with the 4–4–2 at Milan in the 1990s) was criticised for playing an "increasingly outdated" 4–4–2 formation.[15]

One reason for the partially discontinued use of the 4–4–2 formation at the highest level of the game is its lack of central dominance against other formations like a 4–3–3, due to having only 2 central midfielders. Being outnumbered in the central area of the pitch makes it more difficult to both obtain and retain the ball against formations that utilize three or more midfielders centrally. To combat these issues, variations of the classic formation have been created, such as the 4–1–2–1–2.

However, the 4–4–2 is still regarded as the best formation to protect the whole width of the field with the opposing team having to get past two banks of four and has recently had a tactical revival having recently contributed to Diego Simeone's Atlético Madrid, Carlo Ancelotti's Real Madrid and Claudio Ranieri's Leicester City.[16][17]

4–4–1–1

[edit]

A variation of 4–4–2 with one of the strikers playing "in the hole", or as a "second striker", slightly behind their partner.[18] The second striker is generally a more creative player, the playmaker, who can drop into midfield to pick up the ball before running with it or passing to teammates.[18] Interpretations of 4–4–1–1 can be slightly muddled, as some might say that the extent to which one forward has dropped off and separated from the other can be debated.

4–4–2 diamond or 4–1–2–1–2

[edit]

The 4–4–2 diamond (also described as 4–1–2–1–2) staggers the midfield. The width in the team has to come from the full-backs pushing forward. The defensive midfielder is sometimes used as a deep-lying playmaker, but needs to remain disciplined and protect the back four behind him.[19] The central attacking midfielder is the creative player, responsible for picking up the ball, and distributing the ball wide to its full-backs or providing the two strikers with through balls.[20] When out of possession, the midfield four must drop and assist the defence, while the two strikers must be free for the counter-attack.[20] Its most famous example was Carlo Ancelotti's Milan, which won the 2003 UEFA Champions League Final and made Milan runners-up in 2005. Milan was obliged to adopt this formation so as to field talented central midfielder Andrea Pirlo, in a period when the position of offensive midfielder was occupied by Rui Costa and later Kaká.[21] This tactic was gradually abandoned by Milan after Andriy Shevchenko's departure in 2006, progressively adopting a "Christmas tree" formation.

4–1–3–2

[edit]The 4–1–3–2 is a variation of the 4–1–2–1–2 and features a strong and talented defensive centre midfielder. This allows the remaining three midfielders to play further forward and more aggressively, and also allows them to pass back to their defensive mid when setting up a play or recovering from a counterattack. The 4–1–3–2 gives a strong presence in the forward middle of the pitch and is considered to be an attacking formation. Opposing teams with fast wingers and strong passing abilities can try to overwhelm the 4–1–3–2 with fast attacks on the wings of the pitch before the three offensive midfielders can fall back to help their defensive line. Valeriy Lobanovskiy is one of the most famous exponents of the formation, using it with Dynamo Kyiv, winning three European trophies in the process. Another example of the 4–1–3–2 in use was the England national team at the 1966 World Cup, managed by Alf Ramsey.

4–3–3

[edit]

The 4–3–3 was a development of the 4–2–4, and was played by the Brazil national team in the 1962 World Cup, although a 4–3–3 had also previously been used by the Uruguay national team in the 1950 and 1954 World Cups. The extra player in midfield allows a stronger defence, and the midfield could be staggered for different effects. The three midfielders normally play closely together to protect the defence, and move laterally across the field as a coordinated unit. The formation is usually played without wide midfielders. The three forwards split across the field to spread the attack, and may be expected to mark the opposition full-backs as opposed to doubling back to assist their own full-backs, as do the wide midfielders in a 4–4–2.

A staggered 4–3–3 involving a defensive midfielder (usually numbered four or six) and two attacking midfielders (numbered eight and ten) was commonplace in Italy, Argentina, and Uruguay during the 1960s and 1970s. The Italian variety of 4–3–3 was simply a modification of WM, by converting one of the two wing-halves to a libero (sweeper), whereas the Argentine and Uruguayan formations were derived from 2–3–5 and retained the notional attacking centre-half. The national team that made this famous was the Dutch team of the 1974 and 1978 World Cups, even though the team won neither.

In club football, the team that brought this formation to the forefront was the famous Ajax team of the early 1970s, which won three European Cups with Johan Cruyff, and Zdeněk Zeman with Foggia in Italy during the late 1980s, where he completely revitalised the movement supporting this formation. It was also the formation with which Norwegian manager Nils Arne Eggen won 15 Norwegian league titles.

Most teams using this formation now use a specialist defensive midfielder. Recent famous examples include the Porto and Chelsea teams coached by José Mourinho, as well as the Barcelona team under Pep Guardiola. Mourinho has also been credited with bringing this formation to England in his first stint with Chelsea, and it is commonly used by Guardiola's Manchester City. Liverpool manager Jürgen Klopp employed a high-pressing 4–3–3 formation with dynamic full-backs and a potent front three (Mohamed Salah, Sadio Mané, Roberto Firmino) to win the Premier League and the UEFA Champions League.[22]

4–3–1–2

[edit]A variation of the 4–3–3 wherein a striker gives way to a central attacking midfielder. The formation focuses on the attacking midfielder moving play through the centre with the strikers on either side. It is a much narrower setup in comparison to the 4–3–3 and is usually dependent on the attacking midfielder to create chances. Examples of sides which won trophies using this formation were the 2002–03 UEFA Cup and 2003–04 UEFA Champions League winners Porto under José Mourinho's; and the 2002–03 UEFA Champions League and 2003–04 Serie A-winning Milan team, and 2009–10 Premier League winners Chelsea, both managed by Carlo Ancelotti. This formation was also adopted by Massimiliano Allegri for the 2010–11 Serie A title-winning season for Milan. It was also the favoured formation of Maurizio Sarri during his time at Empoli between 2012 and 2015, during which time they won promotion to Serie A and subsequently avoided relegation, finishing 15th in the 2014–15 Serie A season.

4–1–2–3

[edit]

The 4-1-2-3 formation is a modern, dynamic system that emphasizes control in midfield, defensive stability, and attacking width. It features a traditional back four, a lone defensive midfielder (CDM), two central midfielders (CMs), and a fluid front three consisting of two wingers and a central striker. This setup allows teams to dominate possession, press effectively, and transition quickly between defense and attack.

A real-world example of a team using this system is Manchester City under Pep Guardiola, especially during the 2022–2023 season. Guardiola often deployed Rodri as the lone CDM, with De Bruyne and Gündoğan operating as advanced midfielders. Wingers like Riyad Mahrez, Jack Grealish, or Phil Foden provided width, while Erling Haaland spearheaded the attack.[citation needed]

4–3–2–1 (the "Christmas tree" formation)

[edit]

The 4–3–2–1, commonly described as the "Christmas tree" formation, has another forward brought on for a midfielder to play "in the hole", so leaving two forwards slightly behind the most forward striker.

Terry Venables and Christian Gross used this formation during their time in charge of Tottenham Hotspur. Since then, the formation has lost its popularity in England.[23] It is, however, most known for being the formation Carlo Ancelotti used on-and-off during his time as a coach with Milan to lead his team to win the 2007 UEFA Champions League title.

In this approach, the middle of the three central midfielders act as a playmaker while one of the attacking midfielders plays in a free role. However, it is also common for the three midfielders to be energetic shuttlers, providing for the individual talent of the two attacking midfielders ahead. The "Christmas tree" formation is considered a relatively narrow formation and depends on full-backs to provide presence in wide areas. The formation is also relatively fluid. During open play, one of the side central midfielders may drift to the flank to add additional presence.

4–2–3–1

[edit]

A flexible formation in prospects to defensive or offensive orientation, as both the wide players and the full-backs may join the attack. In defence, this formation is similar to either the 4–5–1 or 4–4–1–1. It is used to maintain possession of the ball and stop opponent attacks by controlling the midfield area of the field. The lone striker may be very tall and strong to hold the ball up as his midfielders and full-backs join him in attack. The striker could also be very fast. In these cases, the opponent's defence will be forced to fall back early, thereby leaving space for the offensive central midfielder. This formation is used especially when a playmaker is to be highlighted. The variations of personnel used on the flanks in this set-up include using traditional wingers, using inverted wingers or simply using wide midfielders. Different teams and managers have different interpretations of the 4–2–3–1, but one common factor among them all is the presence of the double pivot. The double pivot is the usage of two holding midfielders in front of the defence.[24]

At international level, this formation is used by the Belgian, French, Dutch and German national teams in an asymmetric shape, and often with strikers as wide midfielders or inverted wingers. The formation is also currently used by Brazil as an alternative to the 4–2–4 formation of the late 1950s to 1970. Implemented similarly to how the original 4–2–4 was used back then, use of this formation in this manner is very offensive, creating a six-man attack and a six-man defence tactical layout. The front four attackers are arranged as a pair of wide forwards and a playmaker forward who play in support of a lone striker. Mário Zagallo also considers the Brazil 1970 football team he coached as pioneers of 4–2–3–1.[25]

In recent[when?] years, with full-backs having ever more increasing attacking roles, the wide players (be they deep lying forwards, inverted wingers, attacking wide midfielders) have been tasked with the defensive responsibility to track and pin down the opposition full-backs. Manuel Pellegrini is an avid proponent of this formation, and frequently uses it in the football clubs that he manages.

This formation has been very frequently used by managers all over the world in the modern game. One particularly effective use of it was Liverpool under Rafael Benítez, who deployed Javier Mascherano, Xabi Alonso and Steven Gerrard in central midfield, with Gerrard acting in a more advanced role in order to link up with Fernando Torres, who acted as the central striker. Another notable example at club level is Bayern Munich under Jupp Heynckes at his treble-clinching 2012–13 season. Mauricio Pochettino, Jose Mourinho, Ange Postecoglou and Arne Slot also use this formation. A high point of the 4–2–3–1 was in the 2006 FIFA World Cup, where Raymond Domenech's France and Luiz Felipe Scolari's Portugal used it to great success, with Marcello Lippi's victorious Italy squad also using a loose variation in a 4–4–1–1.

4–2–2–2 (magic rectangle)

[edit]

Often referred to as the "magic rectangle" or "magic square",[26] this formation was used by France under Michel Hidalgo at the 1982 World Cup and Euro 1984, and later by Henri Michel at the 1986 World Cup[27] and a whole generation, for Brazil with Telê Santana, Carlos Alberto Parreira and Vanderlei Luxemburgo, by Arturo Salah and Francisco Maturana in Colombia.[28] The "Magic Rectangle" is formed by combining two box-to-box midfielders with two deep-lying ("hanging") forwards across the midfield. This provides a balance in the distribution of possible moves and adds a dynamic quality to midfield play.

This formation was used by former Real Madrid manager Manuel Pellegrini and met with considerable praise.[29] Pellegrini also used this formation while with Villarreal and Málaga. The formation is closely related to a 4–2–4 previously used by Fernando Riera, Pellegrini's mentor,[30] and that can be traced back to Chile in 1962 who (may have) adopted it from the Frenchman Albert Batteux at the Stade de Reims of 50s.

It is two 6s, two 10s, two number 9s, so our fullbacks do a lot of the work up and down and create the width for us. Sometimes our 10s can sit in the halfspaces or they can pull out wide to create that width. We always need at least one player to create width for the team.

The 4–2–2–2 with a box midfield was deployed by the North Carolina Courage of the NWSL from 2017 to 2021, using a front four with freedom to fluidly switch sides and move wide while served by high-playing fullbacks.[32][31][33] The Courage won the league in three consecutive seasons using the formation and the NWSL playoff championship twice, setting season records in wins, points, and goals scored in the process.[34][35]

This formation had been previously used at Real Madrid by Vanderlei Luxemburgo during his failed stint at the club during the latter part of the 2004–05 season and throughout the 2005–06 season. This formation has been described as being "deeply flawed"[36] and "suicidal".[37] Luxemburgo is not the only one to use this although it had been used earlier by Brazil in the early 1980s.[38][39] At first, Telê Santana, then Carlos Alberto Parreira and Vanderlei Luxemburgo proposed basing the "magic rectangle" on the work of the wing-backs. The rectangle becomes a 3–4–3 on the attack because one of the wing-backs moves downfield.[40]

In another sense, the Colombian 4–2–2–2 is closely related to the 4–4–2 diamond of Brazil, with a style different from the French-Chilean trend and is based on the complementation of a box-to box with 10 classic. It emphasises the triangulation, but especially in the surprise of attack. The 4–2–2–2 formation consists of the standard defensive four (right back, two centre backs, and left back), with two centre midfielders, two support strikers, and two out and out strikers.[41] Similar to the 4–6–0, the formation requires a particularly alert and mobile front four to function. The formation has also been used on occasion by the Brazil national team,[39][42] notably in the 1998 World Cup final.[43]

4–2–1–3

[edit]The somewhat unconventional 4–2–1–3 formation was developed by José Mourinho during his time at Inter Milan.[1] He used it in all the teams he coached, including in the 2010 UEFA Champions League final.[1] By using captain Javier Zanetti and Esteban Cambiasso in holding midfield positions, he was able to push more players to attack. Wesley Sneijder filled the attacking midfield role and the front three operated as three strikers, rather than having a striker and one player on each wing. Using this formation, Mourinho won The Treble with Inter in only his second season in charge of the club.[1]

As the system becomes more developed and flexible, small groups can be identified to work together in more efficient ways by giving them more specific and different roles within the same lines, and numbers like 4–2–1–3, 4–1–2–3 and even 4–2–2–2 occur.[1]

Many of the current systems have three different formations in each third, defending, middle and attacking. The goal is to outnumber the other team in all parts of the field but to not completely wear out all the players on the team using it before the full ninety minutes are up. So, the one single number is confusing as it may not actually look like a 4–2–1–3 when a team is defending or trying to gain possession. In a positive attack, it may look exactly like a 4–2–1–3.[1]

4–5–1

[edit]

4–5–1 is a conservative formation; however, if the two midfield wingers play a more attacking role, it can be likened to 4–3–3. The formation can be used to grind out 0–0 draws or preserve a lead, as the packing of the centre midfield makes it difficult for the opposition to build up play.[44] Because of the "closeness" of the midfield, the opposing team's forwards will often be starved of possession. Due to the lone striker, however, the centre of the midfield does have the responsibility of pushing forward as well. The defensive midfielder will often control the pace of the game.[45]

4–6–0

[edit]A highly unconventional formation, the 4–6–0 is an evolution of the 4–2–3–1 or 4–3–3 in which the centre forward is exchanged for a player who normally plays as a trequartista (that is, in the "hole"). Suggested as a possible formation for the future of football,[46] the formation sacrifices an out-and-out striker for the tactical advantage of a mobile front four attacking from a position that the opposition defenders cannot mark without being pulled out of position.[47] Because of the intelligence and pace required by the front four attackers to create and attack any space left by the opposition defenders, however, the formation requires a very skilful and well-drilled front four. Due to these demanding requirements from the attackers, and the novelty of playing without a proper goalscorer, the formation has been adopted by very few teams, and rarely consistently. As with the development of many formations, the origins and originators are uncertain, but arguably the first reference to a professional team adopting a similar formation is Anghel Iordănescu's Romania in the 1994 World Cup Round of 16, when Romania won 3–2 against Argentina.[48][49]

The first team to adopt the formation systematically was Luciano Spalletti's Roma side during the 2005–06 Serie A season, mostly out of necessity as his "strikerless" formation,[50] and then notably by Alex Ferguson's Manchester United side that won the Premier League and Champions League in 2007–08.[51] The formation was unsuccessfully used by Craig Levein's Scotland against Czech Republic to widespread condemnation.[52][53] At Euro 2012, Spain coach Vicente del Bosque used the 4–6–0 for his side's 1–1 group stage draw against Italy and their 4–0 win versus Italy in the final of the tournament.[54]

3–4–3

[edit]

Using a 3–4–3, the midfielders are expected to split their time between attacking and defending. Having only three dedicated defenders means that if the opposing team breaks through the midfield, they will have a greater chance to score than with a more conventional defensive configuration, such as 4–5–1 or 4–4–2. However, the three forwards allow for a greater concentration on attack. This formation is used by more offensive-minded teams. The formation was famously used by Liverpool under Rafael Benítez during the second half of the 2005 UEFA Champions League final to come back from a three-goal deficit. It was also notably used by Chelsea when they won the Premier League under manager Antonio Conte in the 2016–17 season and when they won the 2021 UEFA Champions League final under Thomas Tuchel.[55][56][57]

3–5–2

[edit]

This formation is similar to 5–3–2, but with some important tweaks: there is usually no sweeper (or libero) but rather three classic centre-backs, and the two wing-backs are oriented more towards the attack. Because of this, the most central midfielder tends to remain further back in order to help prevent counter-attacks. It also differs from the classical 3–5–2 of the WW by having a non-staggered midfield. There are several coaches claiming to be the inventors of this formation, like two-time European Cup winning manager and World Cup runner-up Ernst Happel and the unorthodox and controversial Nikos Alefantos, but the first to successfully employ it at the highest level was Carlos Bilardo, who led Argentina to win the 1986 World Cup using the 3–5–2.[58] The high point of the 3–5–2's influence was the 1990 World Cup, with both finalists, Bilardo's Argentina and Franz Beckenbauer's West Germany employing it.[58]

In the last years of first decade of 2000, Gian Piero Gasperini during his years at Genoa (and later in Atalanta) using this tactical system, in a modern way, with high pressure, speed, strength, one on one defense and ball possession enabling this tactical revival. Later, Italian coach Antonio Conte successfully implemented the 3–5–2 at Juventus, having won three Serie A consecutive titles between 2012 and 2014, the first unbeaten (record in a league championship with 20 contestants) and the last reaching the points record (102).[59] After coaching the Italy national team, Conte used again the 3–5–2 system at Chelsea during the 2016–17 Premier League season, leading the club to the league title and an FA Cup final. In order to properly counteract the additional forward pressure from the wing-backs in the system, other sides, including Ronald Koeman's Everton and Mauricio Pochettino's Tottenham, also used the formation against Chelsea.[60][61] At international level, Louis van Gaal utilised 3–5–2 with the Netherlands in the 2014 World Cup, in which they finished third.[62] Notably, this formation was specifically employed as a counter to the challenge of possession football used by the Spanish national side. Cesare Prandelli used it for Italy's 1–1 draw with Spain in the group stage of Euro 2012, with some commentators seeing Daniele De Rossi as a sweeper.[63] The Netherlands used it to greater effect against Spain during the group stage of the 2014 World Cup, completing a 5–1 win. This minimised the Dutch weaknesses (inexperience in defence) and maximising their strengths (world-class forwards in Robin van Persie and Arjen Robben).[64]

Simone Inzaghi, who succeeded Conte at Inter in 2021, has helped modernize and further innovate the 3–5–2. Inzaghi's system builds ball possession through the goalkeeper and defenders and uses midfielders who are quick and technical and capable of defending very well. Particularly innovative was his use of side midfielders, called Quinti ("fifths") such as Federico Dimarco. Dimarco was used in a very flexible way with defensive duties in the non-possession phase (playing in the defensive line in a 5–3–2 shape), but would shift in the offensive phase. The two midfield sidemen would go up on the line of the attackers forming a four-man attack in a 3–3–4 shape.[65] In three seasons Inter six four trophies along with an appearance in the 2023 UEFA Champions League final.[66]

3–2–4–1

[edit]Manager Pep Guardiola used this formation at times in his time at Manchester City, using one main centre-back and two defensive midfield anchors.[67] It begins as a typical 4–2–3–1 formation, but differs in attack, with the left or right half-back sliding into a defensive midfield position, and a defensive midfielder sliding up to create the "square" in midfield. The formation helped Manchester City to win the UEFA Champions League for the first time, and the continental treble in the 2022–23 season.

3–4–1–2

[edit]3–4–1–2 is a variant of 3–5–2 where the wingers are more withdrawn in favour of one of the central midfielders being pushed further upfield into the "number 10" playmaker position. Martin O'Neill used this formation during the early years of his reign as Celtic manager, noticeably taking them to the 2003 UEFA Cup Final. Portland Thorns used a 3–4–1–2 formation to win the 2017 NWSL championship, withdrawing forward Christine Sinclair into the playmaker role rather than moving a midfielder up. The Thorns transitioned to a 4–2–3–1 in 2018 after opposing teams countered the 3–4–1–2 with a stronger midfield presence.[68][69]

3–6–1

[edit]

This uncommon modern formation focuses on ball possession in the midfield.[70] In fact, it is very rare to see it as an initial formation, as it is more useful for maintaining a lead or a draw. Its more common variants are 3–4–2–1 or 3–4–3 diamond, which use two wing-backs. The lone forward must be tactically gifted, not only because he focuses on scoring but also on assisting with back passes to his teammates. Once the team is leading the game, there is an even stronger tactical focus on ball control, short passes and running down the clock. On the other hand, when the team is losing, at least one of the playmakers will more frequently play on the edge of the area to add depth to the attack. Steve Sampson (for the United States at the 1998 World Cup) and Guus Hiddink (for Australia at the 2006 World Cup) are two of the few coaches who have used this formation. Hiddink used the 3–3–3–1 formation for the Socceroos as well.

3–3–1–3

[edit]The 3–3–1–3 was formed of a modification to the Dutch 4–3–3 system Ajax had developed. Coaches like Louis van Gaal and Johan Cruyff brought it to even further attacking extremes and the system eventually found its way to Barcelona, where players such as Andrés Iniesta and Xavi were reared into 3–3–1–3's philosophy. It demands intense pressing high up the pitch especially from the forwards, and also an extremely high defensive line, basically playing the whole game inside the opponent's half. It requires extreme technical precision and rapid ball circulation since one slip or dispossession can result in a vulnerable counter-attack situation. Cruyff's variant relied on a flatter and wider midfield, but Van Gaal used an offensive midfielder and midfield diamond to link up with the front three more effectively. Marcelo Bielsa has used the system with some success with Argentina and Chile's national teams, and is currently one of the few high-profile managers to use the system in competition today. Diego Simeone had also tried it occasionally at River Plate.

3–3–3–1

[edit]The 3–3–3–1 system is a very attacking formation and its compact nature is ideally suited for midfield domination and ball possession. It means a coach can field more attacking players and add extra strength through the spine of the team. The attacking three are usually two wing-backs or wingers with the central player of the three occupying a central attacking midfield or second striker role behind the centre forward. The midfield three consists of two centre midfielders ahead of one central defensive midfielder or alternatively one central midfielder and two defensive midfielders. The defensive three can consist of three centre backs or one centre back with a full back either side.

The 3–3–3–1 formation was used by Marcelo Bielsa's Chile in the 2010 World Cup, with three centre-backs paired with two wing-backs and a holding player, although a variation is the practical hourglass, using three wide players, a narrow three, a wide three and a centre-forward.[71]

5–2–2–1

[edit]The 5–2–2–1 formation in football is a defensive-oriented system with a focus on counter-attacking. It utilizes five defenders, including three center-backs and two wing-backs, two central midfielders, two attacking midfielders or inside forwards, and one striker at the top. The three center-backs provide a solid defensive foundation, while the wing-backs offer width and versatility by pushing forward to support attacks or dropping back to help in defense. The two central midfielders act as both defensive shields and playmakers, controlling the tempo and transitioning the play from defense to attack. The two attacking midfielders support the lone striker, often operating in spaces between the opposition’s defense and midfield to create chances.

One of the main strengths of this formation is its defensive stability combined with the ability to launch quick counter-attacks through the wing-backs and attacking midfielders. However, it can struggle against teams that overload the midfield, as only two central midfielders are responsible for controlling this area, potentially leaving gaps in ball possession.[72]

5–3–2

[edit]

This formation has three central defenders, possibly with one acting as a sweeper. This system merges the winger and full-back positions into the wing-back, whose job it is to work their flank along the full length of the pitch, supporting both the defence and the attack.[73] At club level, the 5–3–2 was famously employed by Helenio Herrera in his Inter Milan side of the 1960s and 1970s, influencing many other Italian teams of the era.[74] The Brazil team which won the 2002 FIFA World Cups also employed this formation with their wing-backs Cafu and Roberto Carlos two of the best known proponents of this position.[75][76]

5–3–2 with sweeper or 1–4–3–2

[edit]A variant of the 5–3–2, this involves a more withdrawn sweeper, who may join the midfield, and more advanced full-backs. The 1990 world champion West German team was known for employing this tactic under Franz Beckenbauer, with his successor Berti Vogts retaining the scheme with some variations during his tenure.

5–4–1

[edit]

This is a particularly defensive formation, with an isolated forward and a packed defence. Again, however, a couple of attacking full-backs can make this formation resemble something like a 3–6–1. One of the most famous cases of its use is the Euro 2004-winning Greek national team.

Incomplete formations

[edit]When a player is sent off (i.e. after being shown a red card) or leaves the field due to an injury or other reason with no ability to be replaced with a substitute, teams generally fall back to defensive formations such as 4–4–1, 5–3–1 or even 5-4-0. Often only when facing a negative result will a team with ten players play in a risky attacking formation such as 4–3–2, 3–4–2, or even 4–2–3. If one or more players are also sent off, teams often adopt all-out attacking or all-out defensive formations, depending on the score. If two players are sent off or hurt, the common formations are a 4-4-0 hoping to block attacks until the game is over, or a 4-3-1 where the 3 man midfield & 1 man up front will slide across in defence and creating chances with long through balls hoping for the fast striker to beat the defence with speed.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Murphy, Brenden (2007). From Sheffield with Love. SportsBooks Limited. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-899807-56-7.

- ^ Sengupta, Somnath (29 July 2011). "Tactical Evolution Of Indian Football (Part One): Profiling Three Great 2-3-5 Teams". thehardtackle.com. Kolkata: The Hard Tackle. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ "England's Uniforms — Shirt Numbers and Names". Englandfootballonline.com. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Ingle, Sean (15 November 2000). "Knowledge Unlimited: What a refreshing tactic". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 10 July 2006.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (26 October 2010). "The Question: Are Barcelona reinventing the W-W formation?". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Araos, Christian. "NYCFC comfortable in unconventional formation". Empire of Soccer. Archived from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Andrea Schianchi (2 November 2014). "Nereo Rocco, l'inventore del catenaccio che diventò Paròn d'Europa" (in Italian). La Gazzetta dello Sport. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ Tobias Escher (6 June 2014). "Liveanalyse des WM-Finals 1954" [Analysis of the 1954 World Cup Final] (in German).

- ^ a b c "Gusztáv Sebes (biography)". FIFA. Archived from the original on 8 December 2006. Retrieved 10 July 2006.

- ^ a b Lutz, Walter (11 September 2000). "The 4–2–4 system takes Brazil to two World Cup victories". FIFA. Archived from the original on 9 January 2006. Retrieved 10 July 2006.

- ^ "Sebes' gift to football". UEFA. 21 November 2003. Archived from the original on 23 November 2003. Retrieved 10 July 2006.

- ^ "Formations: 4–4–2". BBC News. 1 September 2005. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "National Soccer Coaches Association of America". Nscaa.com. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (18 December 2008). "The Question: why has 4–4–2 been superseded by 4–2–3–1?". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "England's World Cup disaster exposes the antiquity of 4–4–2". CNN. 30 June 2010. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Why is 4-4-2 thriving? Is it the key to Leicester and Watford's success?".

- ^ "The Rebirth of 4-4-2". 19 February 2016. Archived from the original on 25 February 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ a b "Formations: 4–4–1–1". BBC News. 1 September 2005. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Srivastava, Aniket (18 May 2005). "Explaining the Role of a CDM". Manager Pro. Protege Sports. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ a b "Tactical Analysis: The 4-1-2-1-2 Formation". Shorthand Social. 25 March 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ "News – Notizie, rassegna stampa, ultim'ora, calcio mercato". A.C. Milan. Archived from the original on 21 April 2009. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Dominating the Pitch: The Versatile 4-3-3 formation in Football". Lineup builder. 11 October 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ^ Leach, Conrad (13 March 2015). "The Premier League tinker table and formation popularity in 2014-15 - Conrad Leach". The Guardian.

- ^ "Football Tactics for Beginners: The 4-2-3-1 formation". The False 9. 9 November 2013. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015.

- ^ "Zagallo at 80 – A legend of football".

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (1 July 2010). "Brazil vs Netherlands quarterfinal matchup is potentially a classic". si.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ^ "The Magic – Recreating Le Carré Magique – FM2011 Story Forum – Neoseeker Forums". Neoseeker.com. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Sistemas de Juego: [Capítulo I : 4–4–2] – Fútbol Gol". Futbolgol.es. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "I Like Pellegrini's 4–2–2–2 formation — Real Madrid Star Kaka". Goal.com. 19 September 2009. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ "El hombre que cambió la vida a Pellegrini". Marca. Spain. 2 June 2009. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ a b Halloran, John D (20 September 2018). "Halloran: Dissecting the Courage's box midfield". The Equalizer. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Jenkins, Joey. "North Carolina Courage: In Possession". Total Football Analysis Magazine. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Denise. "PEPSI MAX Roadshow | Denise O'Sullivan | Irish hopes and Life in America". Off The Ball (Interview). Interviewed by Nathan Murphy.

Here with the Courage, we play a 4–2–2–2, a box formation, and I'm that 6 in there with another 6 next to me, and you always get on the ball in this formation and spray it out to your fullbacks. You know, you have to be underneath your fullbacks to get it back, getting your 10s into the game. ... It is two 6s, two 10s, two number 9s, so our fullbacks do a lot of the work up and down and create the width for us. Sometimes our 10s can sit in the halfspaces or they can pull out wide to create that width. We always need at least one player to create width for the team.

- ^ Lowery, Joseph (28 October 2019). "How the Courage tactically dismantled the Red Stars en route to the NWSL title". The Athletic. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Kassouf, Jeff (28 May 2021). "NWSL Results: Courage set the record straight with 5-0 win over Louisville". The Equalizer. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ "Real Madrid manager madness: Spurs flop Juande Ramos becomes 10th in 10 years". Mirrorfootball.co.uk. 9 December 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ "Curses, wallies and the return of the Russian linesman". Fourfourtwo.com. Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (24 June 2009). "The Question: How is Brazil's 4–2–3–1 different from a European 4–2–3–1?". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ a b "Tim Vickery column". BBC News. 2 April 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ ""El cuadrado mágico nace con los ángulos mágicos" – Luxemburgo". AS.com. 7 September 2005. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "4–2–2–2". Football-lineups.com. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Roberticus (19 May 2009). "santapelota: Overview of Brazilian Football Part II". Santapelota.blogspot.com. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ "FIFA World Cup Finals — France 1998". Cartage.org.lb. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ "Formations:A Guide to Formations". worldsoccer.about.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ "Formations: 4–5–1". BBC News. 1 September 2005. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (8 June 2008). "The end of forward thinking". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- ^ "Gramsci's Kingdom:Football, Politics, The World: July 2008". 10 July 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- ^ Smyth, Rob (22 January 2010). "The Joy of Six: Counter-attacking goals". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ "ROMANIA — ARGENTINA 3–2 Match report".

- ^ Moore, Malcolm (5 June 2008). "Chelsea and Roman Abramovich may be drawn to Luciano Spalletti's style at Roma". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (2008). Inverting the Pyramid. London: Orion Books. pp. 350–2. ISBN 978-0-7528-8995-5.

- ^ Grahame, Ewing (11 October 2010). "Scotland v Spain: Craig Levein defends his strikerless 4–6–0 formation". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ Murray, Ewan (8 October 2010). "Czech Republic 1-0 Scotland | Euro 2012 Group I match report". the Guardian. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ "Euro 2012: 7 Strategies to Counter Spain's 4–6–0 Formation". Bleacher Report.

- ^ Pasztor, David (20 November 2016). "Antonio Conte earns the approval of 'The Godfather of the 343'". WeAin'tGotNoHistory. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Smith, Cain (31 March 2020). "How Antonio Conte's Chelsea Won The Premier League with a Back 3". World Football Index. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Tuchel reflects on winning the tactical battle against Guardiola yet again". We Ain't Got No History. 30 May 2021.

- ^ a b Wilson, Jonathan (19 November 2008). "The Question: is 3–5–2 dead?". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- ^ FourFourTwo; Guardian, The; Squawka; Goal; Soccer, World; Comes, When Saturday; A, The Blizzard He writes predominantly on Serie; League, the Premier (24 March 2015). "From the Catenaccio to the 3-5-2: Italy's love affair with tactics and strategy • Outside of the Boot". Outside of the Boot. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Barney Ronay (13 May 2017). "Antonio Conte's brilliance has turned Chelsea's pop-up team into champions". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ^ Thore Haugstad (5 January 2017). "Pochettino copies Conte, Tottenham thwart Costa to deny Chelsea". ESPN. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (29 August 2014). "Why is Louis van Gaal so hell-bent on using 3-5-2 at Manchester United?". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Yap, Kelvin (11 June 2012). "Spain too smart for their own good". ESPN Star. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ Ramesh, Priya (18 June 2014). "Tactical Analysis: How the Netherlands demolished Spain". Benefoot.net. Archived from the original on 21 June 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ^ "Analisi Tattica: l'Inter di Simone Inzaghi 2022-2023". 23 February 2023.

- ^ "Il capolavoro tattico di Inzaghi: Come ha normalizzato il City". 11 June 2023.

- ^ "Pep Guardiola's Premier League Triumph: Mastering the 3–2–4–1 Formation" (Press release). Breaking the Lines. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ "Inside PTFC" (Press release). Portland Timbers. 23 May 2018. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Murray, Caitlin (23 August 2018). "Midge Purce realizes a dream in Portland after enduring the nightmare of the Breakers' demise". The Athletic. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

At the dispersal draft, we knew we were going to do the 3-4-1-2 with wing backs and (Margaret Purce) was the perfect fit. ... we had one that was almost crafted for her—as a wing back, she gets to be a winger and a fullback.

- ^ Marić, René. "The 3-6-1: A logical step". Spielverlagerung.com (in German). Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (25 May 2012). "The Question: How best for Manchester United to combat Barcelona?". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "5-2-2-1 Formation". Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- ^ "Formations: 3–5–2". BBC News. 1 September 2005. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Helenio Herrera: The Architect Of La Grande Inter Sempreinter.com, Retrieved 29 November 2019

- ^ "A brief history of Brazilian full-backs". 12 October 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ Daniel, Jacob (11 April 2024). The Complete Guide to Coaching Soccer Systems and Tactics. Reedswain Inc. ISBN 978-1-59164-136-0.