Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

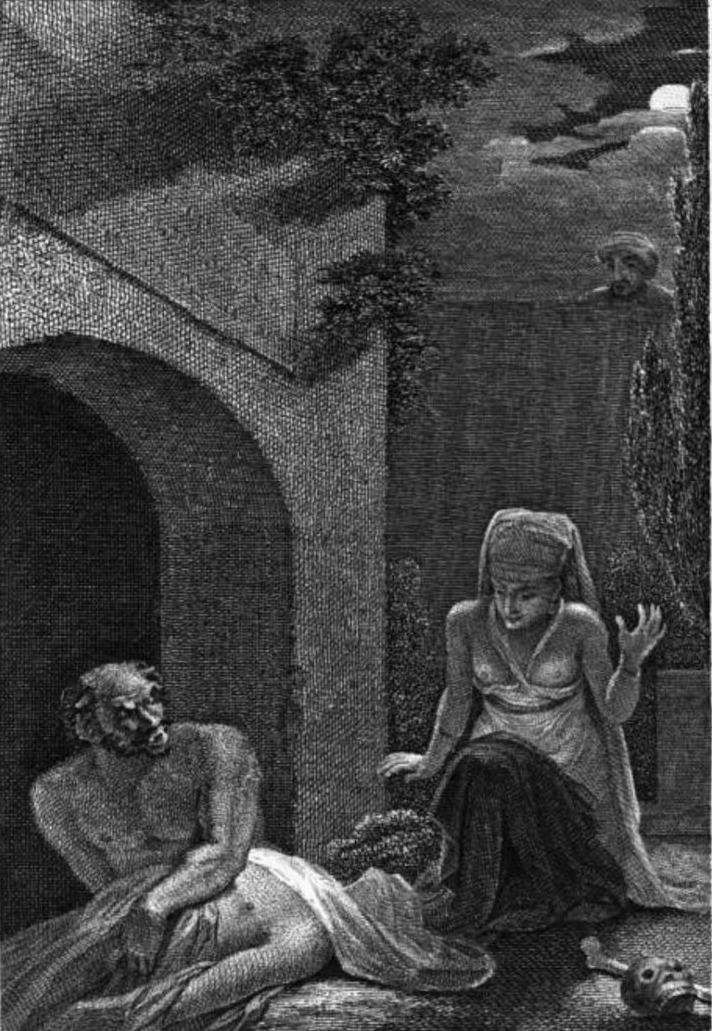

Ghoul

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

In folklore, a ghoul (from Arabic: غول, ghūl) is a demon-like being or monstrous humanoid, often associated with graveyards and the consumption of human flesh. The concept of the ghoul originated in pre-Islamic Arabian religion.[1] Modern fiction often uses the term to label a specific kind of monster.

By extension, the word "ghoul" is also used in a derogatory sense to refer to a person who delights in the macabre or whose occupation directly involves death, such as a gravedigger or graverobber.[2]

Etymology

[edit]The English word ghoul is from the Arabic غُول (ghūl), from غَالَ (ghāla) 'to seize'.[3][4][a] The term was first used in English literature in 1786 in William Beckford's Orientalist novel Vathek,[6] which describes the ghūl of Arabic folklore. This definition of the ghoul has persisted into modern times, with ghouls appearing in popular culture.[2]

In early Arabic, the term is treated as a feminine word. Later, the term became treated as a masculine word, and ghouls became perceived as masculine creatures with Sila as feminine counterpart.[7]

Folklore

[edit]In Arabic folklore, the ghul is said to dwell in cemeteries and other uninhabited places. A male ghoul is referred to as ghul while the female is called ghulah.[8] Scholar Dwight F. Reynolds identifies the Arabic ghoul as a female creature – sometimes called "Mother Ghoul" (ʾUmm Ghulah), "Our Aunt Ghoul", or a similar relational term – in tales told to girls and young women. In these tales, the ghoul appears to men as a long-lost female relative or an unassuming old woman; she uses this glamor[b] to lure the hapless characters, who are usually husbands or fathers, into her home, where she can eat them. The male characters' female relatives can often see through the illusion and warn them of the danger; the men survive if they believe the women (and are eaten if they do not).[10]

An example of this can be found in a Syrian folktale, The Woodcutter's Wealthy Sister or The Woodcutter's Weary Wife, which was adapted into an animated story in the series Britannica's Tales Around the World. A poor, arrogant and spiteful woodcutter encounters a beautiful, wealthy princess who claims to be his long-lost sister, even though he had no sisters at all. The woodcutter accepts the mysterious princess's invitation to bring him, his abused wife and their numerous children to her palace to live in luxury. However, the wife discovers that the "princess" is in fact a female ghoul (simply referred to as a "monster" in the Britannica adaptation) who is planning to eat the woodcutter and his family. After narrowly escaping the ghoul's attempts to eat them, the wife and her children flee the palace in the night and leave the woodcutter to be devoured by the ghoul.[11]

The ghoul is said to lure unwary people into the desert wastes or abandoned places to slay and devour them. The creature also preys on young children, drinks blood, steals coins, eats the dead,[12] and takes the form of the person most recently eaten. One of the narratives identified a ghoul named Ghul-e Biyaban, a particularly monstrous character believed to be inhabiting the wilderness of Afghanistan and Iran.[13] A hyena who attacked a woman in Mecca in 1667 was referred to by locals as a ghul, possibly due to a perceived similarity to the creature of folklore.[14]

Al-Dimashqi describes the ghoul as cave-dwelling animals who only leave at night and avoid the light of the sun. They would eat both humans and animals.[15]

It was not until Antoine Galland translated One Thousand and One Nights into French that the Western concept of ghouls was introduced into European society.[2] Galland depicted the ghoul as a monstrous creature that dwelled in cemeteries, feasting upon corpses.

Similar creatures

[edit]In ancient Mesopotamia, there were demonic entities known as Gallu, which scholar Ahmed Al-Rawi believes may have influenced the Arabic ghoul via early contact between Bedouin traders and Akkadians.[c] The Gallu was an Akkadian underworld demon, associated with the stories of Dumuzid and Inanna.[17][5][16]

Arabic and Islamic literature

[edit]Ghouls belong to the jinn attested in pre-Islamic Arabic poetry.[18] A famous poem narrates about a fight between Ta'abbata Sharra and a ghoul.[18] Belief in ghouls was not universally accepted in Islam; the Mu'tazilites denied their existence.[18] Al-Jahiz denounced Ta'abbata Sharra for boasting about his victory over the ghoul.[18]

Although not mentioned in the Quran, ghouls appear in hadith. Al-Masudi reports that on his journey to Syria, Umar slew a ghoul with his sword.[19] In one[which?] hadith it is said, lonely travelers can escape a ghoul's attack by reciting the adhan (call to prayer).[20] Unlike demons, a ghoul may convert to Islam when reciting the Throne Verse.[21]

The ghoul could appear in male and female shape, but usually appeared female to lure male travelers to devour them.[19] According to History of the Prophets and Kings, the rebellious (maradatuhum) among the devils and the ghouls have been chased away to the deserts and mountains and valleys a long time ago.[22]

Modern ghoul

[edit]The word ghoul entered the English tradition and was further identified as a grave-robbing creature that feeds on dead bodies and children. In the West, ghouls have no specific shape and have been described by Edgar Allan Poe as "neither man nor woman... neither brute nor human."[23]

In "Pickman's Model", a short story by H. P. Lovecraft, ghouls are members of a subterranean race. Their diet of dead human flesh mutated them into bestial humanoids able to carry on intelligent conversations with the living. The story has ghouls set underground with ghoul tunnels that connect ancient human ruins with deep underworlds. Lovecraft hints that the ghouls emerge in subway tunnels to feed on train wreck victims.[24]

Lovecraft's vision of the ghoul, shared by associated authors Clark Ashton-Smith and Robert E. Howard, has heavily influenced the collective idea of the ghoul in American culture. Ghouls as described by Lovecraft are dog-faced and hideous creatures but not necessarily malicious. Though their primary (perhaps only) food source is human flesh, they do not seek out or hunt living people. They are able to travel back and forth through the wall of sleep. This is demonstrated in Lovecraft's "The Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath" in which Randolph Carter encounters Pickman in the dream world after his complete transition into a mature ghoul.

Ghouls in this vein are also changelings in the traditional way. The ghoul parent abducts a human infant and replaces it with one of its own. Ghouls appear entirely human as children but begin to take on the "ghoulish" appearance as they age past adulthood. The fate of the replaced human children is not entirely clear but Pickman offers a clue in the form of a painting depicting mature ghouls as they encourage a human child while it cannibalizes a corpse. This version of the ghoul appears in stories by authors such as Neil Gaiman, Brian Lumley, and Guillermo del Toro.

See also

[edit]- Lists of legendary creatures

- Bogeyman – Mythological antagonist

- Ogre – Legendary monster

- Pop – Cannibalistic spirit of Thai folklore

- Preta – Type of supernatural being in South and East Asian religions

- Vrykolakas – Vampiric undead creature in Greek folklore

- Wendigo – Mythical being in Native American folklore

- Jikininki – Short story by Lafcadio Hearn

- Ghoul (miniseries)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Earlier etymologies have also suggested the word comes from an Arabic word meaning 'to kill'. Scholar Ahmed Al-Rawi writes: "Abū al-Fail Ibn Manūr (1232–1311 C.E.) in Lisān al-‘Arab states that the term 'ghoul' stems from a verbal root 'ghāl' meaning 'to kill', and al-‘Ābād mentions in al-Mu ī fī ’l-Lughah that the term ghoul means 'death' as it is originally derived from the Arabic verb ightāl, which means 'to murder'."[5]

- ^ In the older sense of a spell or illusion which makes the user appear fascinating or appealing.[9]

- ^ Arab traders have been attested in Mesopotamian cuneiform, and there is evidence of cultural exchange between Arabs and their neighbors.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ El-Zein, Amira (2009). Islam, Arabs, and the intelligent world of the jinn. Contemporary Issues in the Middle East (1st ed.). Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-8156-5070-6. JSTOR j.ctt1j5d836. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Al-Rawi, Ahmed K. (November 2009). "The Arabic Ghoul and its Western Transformation". Folklore. 120 (3): 291–306. doi:10.1080/00155870903219730. ISSN 0015-587X. JSTOR 40646532. S2CID 162261281.

- ^ Robert Lebling (30 July 2010). Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar. I.B.Tauris. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-0-85773-063-3.

- ^ "Ghoul, N." Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, December 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/2239227052.

- ^ a b Al-Rawi, Ahmed (2009). "The Mythical Ghoul in Arabic Culture" (PDF). Cultural Analysis. 8: 45–69. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 December 2024.

- ^ "Ghoul Facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Ghoul". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ Jones, Alan. "Early Arabic poetry: select poems." (No Title) (2011) p. 243

- ^ Steiger, Brad (2011). The Werewolf Book: The Encyclopedia of Shape-Shifting Beings. Canton, MI: Visible Ink Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-57859-367-5.

- ^ “ "Glamour, N." Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, December 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/7392208089.

- ^ Reynolds, Dwight F. (2015). Reynolds, Dwight F (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Modern Arab Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 260. doi:10.1017/CCO9781139021708. ISBN 978-0-521-89807-2.

- ^ The Woodcutter’s Weary Wife

- ^ "ghoul". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved 22 January 2006.

- ^ Melton, J Gordon (2010). The Vampire Book: The Encyclopedia of the Undead. Canton, MI: Visible Ink Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-1-57859-281-4.

- ^ Wetmore Jr, Kevin J. (16 September 2021). Eaters of the Dead: Myths and Realities of Cannibal Monsters. Reaktion Books. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-78914-445-1.

- ^ Nünlist, Tobias (2015). Dämonenglaube im Islam [Demonic Belief in Islam] (in German). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 189. ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4.

- ^ a b Al-Rawi, Ahmed. Supernatural Creatures in Arabic Literary Tradition. Taylor & Francis, 2023. pp. 19–36.

- ^ Black, Jeremy; Cunningham, Graham; Flückiger-Hawker, Esther; Robson, Eleanor; Taylor, John; Zólyomi, Gábor. "Inana's descent to the netherworld". Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Oxford University. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d Jones, Alan. "Early Arabic poetry: select poems." (No Title) (2011). p. 241

- ^ a b Böttcher, Annabelle; Krawietz, Birgit, eds. (2021). Islam, Migration and Jinn: Spiritual Medicine in Muslim Health Management. The Modern Muslim World (1st ed.). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 29. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-61247-4. ISBN 978-3-030-61246-7. ISSN 2945-6134. S2CID 243448335. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ Böttcher & Krawietz 2021, p. 28.

- ^ El-Zein 2009, p. 140.

- ^ Abedinifard, Mostafa; Azadibougar, Omid; Vafa, Amirhossein, eds. (2021). Persian literature as world literature. New York, NY: Bloomsbury. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-5013-5422-9. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ "Ghoul". britannica. 4 October 2024.

- ^ Lamb, Robert (11 October 2011). "How Ghouls Work".