Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

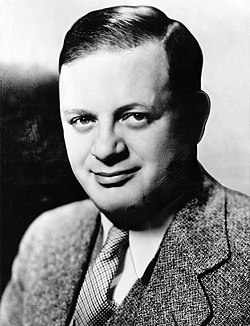

Herman J. Mankiewicz

View on WikipediaThis article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (February 2025) |

Herman Jacob Mankiewicz (/ˈmæŋkəwɪts/ MANG-kə-wits; November 7, 1897 – March 5, 1953) was an American screenwriter who, with Orson Welles, wrote the screenplay for Citizen Kane (1941). Both Mankiewicz and Welles went on to receive the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay for the film. Mankiewicz was previously a Berlin correspondent for Women’s Wear Daily,[1] assistant theater editor at The New York Times,[1] and the first regular drama critic at The New Yorker.[1][2][3][4] Alexander Woollcott said that Mankiewicz was the "funniest man in New York".[5][6]

Key Information

Mankiewicz was often asked to fix other writers' screenplays, with much of his work uncredited. His writing style became valued in the films of the 1930s—a style that included a slick, satirical, and witty humor, in which dialogue almost totally carried the film, and which eventually become associated with the "typical American film" of that period.[7]: 219 In addition to Citizen Kane, he wrote or worked on films including The Wizard of Oz, Man of the World, Dinner at Eight, The Pride of the Yankees and The Pride of St. Louis.

Film critic Pauline Kael credits Mankiewicz with having written, alone or with others, "about forty of the films I remember best from the twenties and thirties...He was a key linking figure in just the kind of movies my friends and I loved best."[8]: 247 Nearly seventy years after his death, Mankiewicz was portrayed by actor Gary Oldman in the 2020 Oscar-winning film Mank.

Early life

[edit]Mankiewicz was born in New York City in 1897. His parents were German-Jewish immigrants: his father, Franz Mankiewicz, was born in Berlin and emigrated to the U.S. from Hamburg in 1892.[5][9][10] In New York he met his wife, Johanna Blumenau,[1] a seamstress from the German-speaking Kurland region of Latvia.[11]: 21 The family lived first in New York, then moved to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, where Herman's father accepted a teaching position. In 1909, Herman's brother, Joseph L. Mankiewicz—who later became a successful writer, producer, and director—was born, and both boys and a sister, Erna,[12][13] spent their childhood there. Census records indicate the family lived on Academy Street.[citation needed]

Mankiewicz was described as a "bookish, introspective child who, despite his intelligence, was never able to win approval from his demanding father" who was known to belittle his achievements.[7]: 218–224 The family moved to New York City in 1913, where Herman's father accepted a teaching position, at Stuyvesant High School,[14] and Herman graduated from Columbia College in 1917 where he was the “Off-Hour” editor of the Columbia Spectator student newspaper.[5]

Early career

[edit]After a period as managing editor of the American Jewish Chronicle and a reporter at the New York Tribune,[15] he joined the United States Army Air Service to fly planes, but because of airsickness, enlisted instead as a private first class with the Marines, A.E.F.[16][17][18] In 1919 and 1920, he was director of the American Red Cross News Service in Paris.[15]

Marriage

[edit]After returning to the U.S., he married Sara Aaronson of Baltimore. He took her overseas on his next job as a newspaper writer in Berlin from 1920 to 1922; then returned to the U.S. to do political reporting for George Seldes on the Chicago Tribune.[8]: 243–244 Herman and Sara had three children: screenwriter Don Mankiewicz (1922–2015), political adviser Frank Mankiewicz (1924–2014), and novelist Johanna Mankiewicz Davis[19][20] (1937–1974).

Reporter, publicist, playwright

[edit]While a reporter in Berlin, Mankiewicz also sent pieces on drama and books to The New York Times.[3][4] At one point he was hired in Berlin by dancer Isadora Duncan to be her publicist in preparation for her return tour in the United States. At home again in the U.S., he took a job as a reporter for the New York World. Known as a "gifted, prodigious writer,"[This quote needs a citation] he contributed to Vanity Fair, The Saturday Evening Post, and numerous other magazines. While still in his twenties, he collaborated with Heywood Broun, Dorothy Parker, Robert E. Sherwood and others on a revue; and collaborated with George S. Kaufman on a play, The Good Fellows, and with Marc Connelly on the play The Wild Man of Borneo (1927). From 1923 to 1926, he was at The New York Times as assistant theater editor to George S. Kaufman, and soon after became the first regular theater critic for The New Yorker, writing a column during 1925 and early 1926. He was a member of the Algonquin Round Table.[21] His writing attracted the notice of film producer Walter Wanger, who offered him a contract to work at Paramount,[1] and Mankiewicz soon moved to Hollywood.[8]: 244

Hollywood

[edit]Early success

[edit]Paramount paid Mankiewicz $400 a week plus bonuses, and by the end of 1927, he was head of Paramount's scenario department. Film critic Pauline Kael wrote about him and the creation of Citizen Kane in "Raising Kane", her 1971 New Yorker article: "In January, 1928, there was a newspaper item reporting that he (Mankiewicz) was in New York 'lining up a new set of newspaper feature writers and playwrights to bring to Hollywood... Most of the newer writers on Paramount's staff who contributed the most successful stories of the past year' were selected by 'Mank.'"[8]: 244 Film historian Scott Eyman notes that Mankiewicz was put in charge of writer recruitment by Paramount. As "a hard-drinking gambler," however, he hired men in his own image, such as Ben Hecht, Bartlett Cormack, Edwin Justus Mayer—writers comfortable with the iconoclasm of big-city newsrooms who would introduce their sardonic worldliness to movie audiences.[22]

Kael notes that "beginning in 1926, Mankiewicz worked on an astounding number of films." In 1927 and 1928, he did the titles (printed dialogue and explanations) for at least twenty-five films starring Clara Bow, Bebe Daniels, Nancy Carroll, Wallace Beery and other public favorites. By then, sound had arrived, and in 1929 he wrote the script and dialogue for The Dummy, and scripts for many other directors, including William Wellman and Josef von Sternberg.[8]

Other screenwriters made large contributions to Hollywood's early sound films, but "probably none larger than Mankiewicz," according to Kael. At the beginning of the Talkies era, he was one of the highest-paid writers in the world, because, Kael writes, "He wrote the kind of movies that were disapproved of as 'fast' and immoral. His heroes weren't soft-eyed and bucolic; he brought good-humored toughness to the movies, and energy and astringency. And the public responded, because it was eager for modern American subjects."[8]: 247 Ben Hecht described him as "a Promethean wit bound in a Promethean body, one of the most entertaining men in existence ... [and] called the 'Central Park West Voltaire' ".[23]: 330

According to Kael, Mankiewicz did not work on every kind of picture. He did not do Westerns, for example; and once, when a studio attempted to punish him for his customary misbehavior by assigning him to a Rin Tin Tin picture, he rebelled by turning in a script that began with the craven dog frightened by a mouse and reached its climax with a house on fire and the dog taking a baby into the flames.[8]: 246 [a]

Style

[edit]Shortly after his arrival on the West Coast, Mankiewicz sent a telegram to journalist-friend Ben Hecht in New York: "Millions are to be grabbed out here and your only competition is idiots. Don't let this get around."[7] In the film The Front Page, when the sheriff asks who threw a bucket out the window, Walter Catlett's character replies, "Judge Mankiewicz threw it," a nod to his friend by Hecht.[25] He attracted other New York writers to Hollywood who contributed to a burst of creative, tough, sardonic styles of writing for the fast-growing movie industry.

Between 1929 and 1935, he worked on at least twenty films, many of which he received no credit for. Between 1930 and 1932 he was either producer or associate producer on four comedies and helped write their screenplays without credit: Laughter, Monkey Business, Horse Feathers, and Million Dollar Legs, which many critics considered one of the funniest comedies of the early 1930s.[7] In 1933, he moved to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer where, along with Frances Marion,[1] he adapted Dinner at Eight, which was based on the George S. Kaufman/Edna Ferber play, and became one of the most popular comedies at that time and remains a "classic" comedy.

In 1933, he went on leave from MGM to write a film warning Americans about the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany. No studio was willing to produce his screenplay, The Mad Dog of Europe,[1] and in 1935, MGM was notified by Joseph Goebbels, the Minister of Education and Propaganda under Hitler, that films written by Mankiewicz could not be shown in Nazi Germany unless his name was removed from the screen credits.[1][26] During World War II, Mankiewicz officially sponsored and took financial responsibility for many refugees fleeing Nazi Germany for the United States.[27]

The Wizard of Oz

[edit]In February 1938, Mankiewicz was assigned as the first of ten screenwriters to work on The Wizard of Oz. Three days after he started writing, he handed in a 17-page treatment of what was later known as "the Kansas sequence". While L. Frank Baum devoted less than a thousand words in his book to Kansas, Mankiewicz almost balanced the attention between Kansas and Oz, feeling it necessary that audiences relate to Dorothy Gale in a real world before she was transported to a magic one. By the end of the week he had finished 56 pages, and included instructions to film the scenes in Kansas in black and white. His goal, according to film historian Aljean Harmetz, was to "capture in pictures what Baum had captured in words—the grey lifelessness of Kansas contrasted with the visual richness of Oz."[28]: 28 He was not credited for his work on the film.

Citizen Kane

[edit]Mankiewicz is best known for his collaboration with Orson Welles on the screenplay of Citizen Kane, for which they shared an Academy Award. The authorship later became a source of controversy. Pauline Kael attributed Kane's screenplay to Mankiewicz in a 1971 essay that was and continues to be strongly disputed.[1][29][30] Much debate has centered on this issue, largely because of the importance of the film itself, which most agree is a fictionalized biography of newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst. According to film biographer David Thomson, however, "No one can now deny Herman Mankiewicz credit for the germ, shape, and pointed language of the screenplay..."[31]

Mankiewicz biographer Richard Meryman notes that the dispute had various causes, including the way the movie was promoted. When RKO opened the movie on Broadway on May 1, 1941, followed by showings at theaters in other large cities, the publicity programs included photographs of Welles as "the one-man band, directing, acting, and writing." In a letter to his father afterwards, Mankiewicz wrote, "I'm particularly furious at the incredibly insolent description of how Orson wrote his masterpiece. The fact is that there isn't one single line in the picture that wasn't in writing—writing from and by me—before ever a camera turned."[11]: 270 Mankiewicz biographer Sydney Ladensohn Stern discounts his assertion as his defensiveness with his father, especially because he and other family members had recently bailed him out financially.[1]

According to film historian Otto Friedrich, it made Mankiewicz "unhappy to hear Welles quoted in Louella Parsons's column, before the question of screen credits was officially settled, as saying, 'So I wrote Citizen Kane.' Mankiewicz went to the Screen Writers Guild and declared that he was the original author. Welles later claimed that he planned on a joint credit all along, but Mankiewicz sometimes claimed that Welles offered him a bonus of ten thousand dollars if he would let Welles take full credit. Welles eventually agreed to share credit with Mankiewicz and furthermore, to list his name first.[1] Sometime later, Welles commented on this allegation:

God, if I hadn't loved him I would have hated him after all those ridiculous stories, persuading people I was offering him money to have his name taken off ... that he would be carrying on like this, denouncing me as a coauthor, screaming around.[11]: 274

Hearst's inner circle

[edit]Mankiewicz became good friends with Hollywood screenwriter Charles Lederer, who was Marion Davies's nephew. Lederer grew up as a Hollywood habitué, spending much time at San Simeon, where Davies reigned as William Randolph Hearst's mistress. As one of Mankiewicz's admirers in the early 1930s, Hearst often invited him to spend the weekend at San Simeon.

"Herman told Joe to come to the office of their mutual friend Charlie Lederer."[11]: 144 "Mankiewicz found himself on story-swapping terms with the power behind it all, Hearst himself. When he had been in Hollywood only a short time, he met Marion Davies and Hearst through his friendship with Charles Lederer, a writer, then in his early twenties, whom Ben Hecht had met and greatly admired in New York when Lederer was still in his teens. Lederer, a child prodigy who had entered college at thirteen, got to know Mankiewicz."[8] : 254–255 Herman eventually "saw Hearst as 'a finagling, calculating, Machiavellian figure.' But also, with Charlie Lederer, ... wrote and had printed parodies of Hearst newspapers."[11]: 212–213

In 1939, Mankiewicz suffered a broken leg in a driving accident and had to be hospitalized. During his hospital stay, one of his visitors was Orson Welles, who met him earlier and had become a great admirer of his wit. During the months after his release from the hospital, he and Welles began working on story ideas which led to the creation of Citizen Kane.

Despite Welles' denial that the film was about Hearst, few people were convinced—including Hearst. After the release of Citizen Kane, Hearst pursued a longtime vendetta against Mankiewicz and Welles for writing the story.[7] "Certain elements in the film were taken from Mankiewicz's own experience: the sled Rosebud was based—according to some sources—on a very important bicycle that was stolen from him. ... [and] some of Kane's speeches are almost verbatim copies of Hearst's."[7] Most personally, the word "rosebud" was reportedly Hearst's private nickname for Davies' clitoris.[32] Hearst's thoughts about the film are unknown; what is certain is that his extensive chain of newspapers and radio stations blocked all mentions of the film, and refused to accept advertising for it, while some Hearst employees worked behind the scenes to block or restrict its distribution.[33]

Academy Award celebration

[edit]Citizen Kane was nominated for an Academy Award in every possible category, including Best Original Screenplay. Meryman writes, "Herman insisted he had no chance to win, though The Hollywood Reporter had given the film first place in ten of its twelve divisions. The fear of Hearst, he felt, was still alive. And Hollywood's resentment and distrust of Welles, the nonconformist upstart, were even greater since he had lived up to his wonderboy ballyhoo."[11]: 272 Neither Welles nor Mankiewicz attended the dinner, which was broadcast on radio. Welles was in South America filming It's All True, and Herman refused to attend. "He did not want to be humiliated," said his wife, Sara.

Richard Meryman describes the evening:

On the night of the awards, Herman turned on his radio and sat in his bedroom chair. Sara lay on the bed. As the screenplay category approached, he pretended to be hardly listening. Suddenly from the radio, half screamed, came "Herman J. Mankiewicz." Welles's name as coauthor was drowned out by voices all through the audience calling out, "Mank! Mank! Where is he?" And audible above all others was Irene Selznick: "Where is he?"[11]: 272

George J. Schaefer accepted Herman's Oscar. "Except for this coauthor award, the Motion Picture Academy excommunicated Orson Welles," wrote Meryman, "[and] as Pauline Kael put it, 'The members of the Academy ... probably felt good because their hearts had gone out to crazy, reckless Mank, their own resident loser-genius."[11]: 272

The film as a whole

[edit]Richard Meryman concludes that "taken as a whole ... Citizen Kane was overwhelmingly Welles's film, a triumph of intense personal magic. Herman was one of the talents, the crucial one, that were mined by Welles. But one marvels at the debt those two self-destroyers owe to each other. Without Welles there would have been no supreme moment for Herman. Without Mankiewicz there would have been no perfect idea at the perfect time for Welles ... to confirm his genius ... The Citizen Kane script was true creative symbiosis, a partnership greater than the sum of its parts."[11]: 275

Alcoholism and death

[edit]Mankiewicz was an alcoholic.[34][35] Ten years before his death, he wrote: "I seem to become more and more of a rat in a trap of my own construction, a trap that I regularly repair whenever there seems to be danger of some opening that will enable me to escape. I haven't decided yet about making it bomb proof. It would seem to involve a lot of unnecessary labor and expense."[36][37] A future Hollywood biographer went so far as to suggest that Mankiewicz’s behavior "made him seem erratic even by the standards of Hollywood drunks."[37]

Mankiewicz died March 5, 1953, at age of 55, of uremic poisoning, the result of liver failure,[38] at Cedars of Lebanon Hospital in Los Angeles.[2][26] Orson Welles said of him, "He saw everything with clarity. No matter how odd or how right or how marvelous his point of view was, it was always diamond white. Nothing muzzy."[37]

Legacy

[edit]In looking back on his early films, Pauline Kael wrote that Mankiewicz had, in fact, written (alone or with others) "about forty of the films I remember best from the twenties and thirties. I hadn't realized how extensive his career was. ... and now that I have looked into Herman Mankiewicz's career it's apparent that he was a key linking figure in just the kind of movies my friends and I loved best. These were the hardest-headed periods of American movies ... [and] the most highly acclaimed directors of that period, suggests that the writers ... in little more than a decade, gave American talkies their character."[8]: 247

Director and screenwriter Nunnally Johnson claimed that the "two most brilliant men he has ever known were George S. Kaufman and Herman Mankiewicz, and that Mankiewicz was the more brilliant of the two. ... [and] spearheaded the movement of that whole Broadway style of wisecracking, fast-talking, cynical-sentimental entertainment onto the national scene."[8]: 246

His friend Ben Hecht wrote this shortly after Mankiewicz's death.

When I remember the dull and inane whom Herman enriched by his presence, and his numbskull "betters" who tried feebly to echo his observations; when I remember his throw-away genius, his modesty, his shrug at adversity; when I remember that unlike the lords of success around him he attacked only the strong with his wit and defended always the weak with his heart, I feel proud to have known a man of importance.[39]

In 2024, Mankiewicz was announced as a posthumous inductee into the Luzerne County Arts & Entertainment Hall of Fame.[40]

Depictions

[edit]Mankiewicz is played by John Malkovich in RKO 281, a 1999 American film about the battle over Citizen Kane.

Mank, a black-and-white Mankiewicz biopic directed by David Fincher and starring Gary Oldman in the title role, was released on Netflix in December 2020.[41] Oldman was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance.

Filmography

[edit]He was involved[42] with the following films:

- The Road to Mandalay (1926) — Writer (story credit)

- Stranded in Paris (1926) — Writer (adaptation)

- Fashions for Women (1927) — Writer

- A Gentleman of Paris (1927) (titles)

- The City Gone Wild (1927) — Writer (titles)

- Honeymoon Hate (1927) — Writer (titles)

- The Gay Defender (1927) — Writer (titles)

- Two Flaming Youths (1927) — Writer (titles)

- Love and Learn (1928) — Writer (titles)

- The Last Command (1928) — Writer (titles)

- Something Always Happens (1928) — Writer (titles)

- A Night of Mystery (1928/I) — Writer (titles)

- Abie's Irish Rose (1928) — Writer (titles)

- His Tiger Lady (1928) — Writer (titles)

- The Dragnet (1928) — Writer (titles)

- The Magnificent Flirt (1928) — Writer (titles)

- The Mating Call (1928) — Writer (titles), Newspaperman (uncredited)

- The Water Hole (1928) — Writer (titles)

- Take Me Home (1928) — Writer (titles)

- Avalanche (1928) — Writer (screenplay) (titles)

- The Barker (1928) — Writer (titles)

- Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1928) — Writer (titles)

- Three Weekends (1928) — Writer (titles)

- What a Night! (1928) — Writer (titles)

- The Love Doctor (1929) — Writer (titles)

- The Canary Murder Case (1929) — Writer (titles)

- The Dummy (1929) — Writer

- The Man I Love (1929) — Writer (story)

- Thunderbolt (1929) — Writer

- The Mighty (1929) — Writer (titles)

- The Vagabond King (1930) — Writer (screenplay) (story)

- Men Are Like That (1930) — Writer (adaptation)

- Honey (1930) — Writer (scenario) (titles)

- Ladies Love Brutes (1930) — Writer (screenplay)

- True to the Navy (1930) — Writer (dialogue)

- Love Among the Millionaires (1930) — Writer (dialogue)

- Laughter (1930) — Writer

- The Royal Family of Broadway (1930) — Writer (adaptation)

- Salga de la cocina (1931) — Writer (adaptation)

- The Front Page (1931) — Bit (uncredited)

- Every Woman Has Something (1931) — Writer (adaptation)

- Man of the World (1931) — Writer (screenplay) (story)

- Ladies' Man (1931) — Writer

- Monkey Business (1931) — producer

- The Lost Squadron (1932) — Writer (additional dialogue)

- Dancers in the Dark (1932) — Writer

- Girl Crazy (1932) — Writer

- Million Dollar Legs (1932) — producer

- Horse Feathers (1932) — producer (uncredited)

- Another Language (1933) — Writer

- Dinner at Eight (1933) — Writer (screenplay)

- Meet the Baron (1933) — Writer

- Duck Soup (1933) — producer (uncredited)

- The Show-Off (1934) — Writer

- Stamboul Quest (1934) — Writer (screenplay)

- After Office Hours (1935) — Writer

- Escapade (1935) — Writer

- Three Maxims (1936) — Writer

- Love in Exile (1936) — Writer

- John Meade's Woman (1937) — Writer

- The Emperor's Candlesticks (1937) — contributor to dialogue (uncredited)

- My Dear Miss Aldrich (1937) — Writer (original story and screenplay)

- It's a Wonderful World (1939) — Writer (story)

- The Wizard of Oz (1939) — Writer (uncredited)

- The Ghost Comes Home (1940) — Writer (contributing writer)

- Comrade X (1940) — Writer (uncredited)

- Keeping Company (1940) — Writer (story)

- The Wild Man of Borneo (1941) — Writer (play)

- Citizen Kane (1941) — Writer (screenplay), Newspaperman (uncredited)

- Rise and Shine (1941) — Writer (screenplay)

- This Time for Keeps (1942) — Writer (characters)

- The Pride of the Yankees (1942) — Writer (screenplay)

- Stand By for Action (1942) — Writer (screenplay)

- The Good Fellows (1943) — Writer (play)

- Christmas Holiday (1944) — Writer

- The Enchanted Cottage (1945) — Writer

- The Spanish Main (1945) — Writer (screenplay)

- A Woman's Secret (1949) — Writer (screenplay), producer

- The Pride of St. Louis (1952) — Writer

- Lux Video Theatre (TV series episode, 1955): The Enchanted Cottage — Writer (original screenplay)

Works

[edit]Essays and reporting

[edit]- H. J. M. (February 28, 1925). "The "World" is with us". Behind the News. The New Yorker. Vol. 1, no. 2. pp. 4–5.

- — (June 6, 1925). "The theatre". Critique. The New Yorker. Vol. 1, no. 16. p. 13.

- — (June 13, 1925). "The theatre". Critique. The New Yorker. Vol. 1, no. 17. p. 15.

Short Fiction

[edit]- Mankiewicz, Herman J., "The Big Game," The New Yorker, November 14, 1925, p. 11

- Mankiewicz, Herman J., "A New Yorker in the provinces," The New Yorker, February 6, 1926, p. 16

- Browning, Tod & Herman J. Mankiewicz (1926). The Road to Mandalay: a Thrilling Throbbing Romance of Singapore. New York: Jacobsen Hodgkinson Corporation. for The Road to Mandalay (1926 film)

Plays

[edit]- Kaufman, George S. & Herman J. Mankiewicz (1931). The good fellow : a play in three acts. New York: S. French.

Critical studies, reviews and biography

[edit]- Meryman, Richard (1978). Mank : the wit, world and life of Herman Mankiewicz.

- Stern, Sydney Ladensohn (2019). The Brothers Mankiewicz: Hope, Heartbreak, and Hollywood Classics

Notes

[edit]- ^ Mankiewicz wrote at least two Jack Holt Westerns, Avalanche and The Water Hole.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Stern, Sydney Ladensohn (2019). The Brothers Mankiewicz: Hope, Heartbreak, and Hollywood Classics. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781617032677.

- ^ a b "Herman Mankiewicz, Film Writer, Dies at 55". Los Angeles Times. March 6, 1953. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ^ a b Young, Toby (2008). How to Lose Friends and Alienate People. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81613-0.

Of all Ben Hecht's colleagues, perhaps the most heroic was Herman J. Mankiewicz, the ex-New York Times journalist who wrote Citizen Kane. ...

[permanent dead link] - ^ a b Robertson, Nan (2009). "Herman J. Mankiewicz". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Herman Jacob Mankiewicz". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- ^ "Citizen Kane (1941)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2009. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Kilbourne, Don (1984). "Herman Mankiewicz (1897–1953)". In Morsberger, Robert E.; Lesser, Stephen O.; Clark, Randall (eds.). Dictionary of Literary Biography. Vol. 26: American Screenwriters. Detroit: Gale Research Company. pp. 218–224. ISBN 978-0-8103-0917-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kael, Pauline. For Keeps (New York, Penguin Books, 1994)

- ^ Dick, Bernard F. (1983). Joseph L. Mankiewicz. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-9291-0.

The father, Franz Mankiewicz, emigrated from Germany in 1892, living first in New York and then moving to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, in to take a job ...

- ^ The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives. Charles Scribner's Sons. 1998. ISBN 0-684-80620-7. Archived from the original on November 22, 2020. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

Mankiewicz was the youngest of three children born to the German immigrants Franz Mankiewicz, a secondary schoolteacher, and Johanna Blumenau, a homemaker.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Meryman, Richard. Mank (New York, William Morrow, 1978)

- ^ "Joseph Mankiewicz Weds. MGM Producer Marries Rose Stradner, Viennese Actress". New York Times. July 29, 1939. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

- ^ "Erna Mankiewicz Stenbuck, 78, Retired New York Schoolteacher". New York Times. August 19, 1979. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Hond, Paul (Fall 2022). "How the Mankiewicz Family Got Their Hollywood Ending". Columbia Magazine. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ a b "OBITUARIES". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. March 6, 1953. p. 22. Retrieved July 7, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ HERMAN J. MANKIEWICZ, Screenwriter - BIOGRAPHY Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ Herman Mankiewicz, Pauline Kael, and the Battle Over “Citizen Kane” The New Yorker via Internet Archive. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ 5 Things You Don’t Know About Herman J. Mankiewicz Algonquin Round Table. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ McFadden, Robert D. (July 27, 1974). "WRITER IS KILLED BY TAXICAB HERE". The New York Times. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ "Education: Q.E.D." TIME. May 26, 1952. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ "Members of the Algonquin Round Table". Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- ^ Eyman, Scott. The Speed of Sound: Hollywood and the Talkie Revolution, 1926–1930, Simon and Schuster (1997)

- ^ Louvish, Simon. Man on the Flying Trapeze: The Life and Times of W.C. Fields, W.W. Norton & Co. (1999)

- ^ "Herman J. Mankiewicz". The American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures Produced in the United States: Feature Films, 1941 – 1950. Archived from the original on March 21, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ "The Front Page". You Tube. March 24, 2025.

- ^ a b "H. J. Mankiewicz, Screenwriter, 56 [sic]. Winner of Academy Award in 1941 Dies. Playwright Was Former Newspaper Man". The New York Times. March 6, 1953. Archived from the original on January 29, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ Spencer, Samuel (December 4, 2020). ""Mank" on Netflix: Did Herman Mankiewicz Bring 100 Refugees to the U.S.?". Newsweek. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean. The Making of the Wizard of Oz, Hyperion (1998)

- ^ Rich, Frank (October 27, 2011). "Roaring at the Screen with Pauline Kael". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 25, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (August 22, 1997). "Welles pic script scrambles H'wood history". Variety. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ Thomson, David, A Biographical Dictionary of Film, 3rd ed. (1995) Alfred A. Knopf

- ^ Topkis, Jay; Vidal, Gore. "Rosebud by Jay Topkis". The New York Review of Books. Nybooks.com. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- ^ Higham, Charles (September 15, 1985). Orson Welles: The Rise and Fall of an American Genius – Charles Higham – Google Books. Macmillan. ISBN 9780312312800. Archived from the original on November 22, 2020. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- ^ Citizen Welles. Scribner. 1989. ISBN 0-684-18982-8. Archived from the original on November 22, 2020. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

Mankiewicz was a screenwriter, a legend of acerbic wit, outrageous social behavior, and advanced alcoholism.

- ^ Orson Welles, a Biography. Hal Leonard Corporation. 1995. ISBN 0-87910-199-7. Archived from the original on November 22, 2020. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

The only problem with Mankiewicz was his notorious alcoholism.

- ^ Stern, Sydney Ladensohn (2019). The Brothers Mankiewicz: Hope, Heartbreak, and Hollywood Classics. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. p. 250. ISBN 9781617032677.

- ^ a b c Eyman, Scott (October 18, 2019). ""The Brothers Mankiewicz" Review: A Steamroller and a Mensch". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on October 28, 2019. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- ^ Green (November 7, 2013). "This Day in Jewish History: Hard-drinking, 'Sell-out' 'Wizard of Oz' Screenwriter Is Born". haaretz.com. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ^ Hecht, Ben (2020). A Child of the Century. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300251791.

- ^ "Luzerne County Arts & Entertainment Hall of Fame announces 2024 induction class". April 13, 2024.

- ^ "Gary Oldman to Star in David Fincher's Biopic of 'Citizen Kane' Co-Writer Herman Mankiewicz". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^

Further reading

[edit]- Kael, Pauline, "Raising Kane", in The Citizen Kane Book, (1971) Bantam Books

- Lambert, Gavin, On Cukor (1972) Putnam

- Marion, Frances, Off With Their Heads (1972) Macmillan

- Naremore, James, The Magic World of Orson Welles (1978) Oxford University Press

External links

[edit]Herman J. Mankiewicz

View on GrokipediaEarly Years

Family Background and Childhood

Herman Jacob Mankiewicz was born on November 7, 1897, in New York City, to German-Jewish immigrants Franz Mankiewicz and Johanna (née Blumenau).[2][7] His father, born in Berlin on November 30, 1872, emigrated to the United States from Hamburg in 1892 at age 20, initially supporting himself through various means before establishing a career as a teacher of modern languages.[8][9] The family soon relocated to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, where Franz worked in education and the household emphasized intellectual pursuits amid modest circumstances.[10][11] Mankiewicz was the eldest child; his sister Erna was born soon after, followed by his brother Joseph L. Mankiewicz on February 11, 1909, also in Wilkes-Barre.[12][13] The siblings grew up in an environment shaped by their father's rigorous academic standards and Germanic discipline, with Franz later advancing his own education by earning a degree from Columbia University at age 41 while teaching.[14] In 1913, the family returned to New York City, where Franz secured a position teaching languages at City College, exposing the children to a vibrant urban intellectual scene.[12][3] Mankiewicz's early years reflected the challenges of immigrant assimilation, including financial strains and familial expectations for scholarly achievement, which his father enforced stringently, often withholding praise despite the boys' talents.[15] This dynamic fostered a competitive atmosphere among the siblings, particularly between Herman and Joseph, influencing their later pursuits in writing and film.[16] The household's emphasis on education and multilingualism provided Mankiewicz with foundational exposure to literature and journalism, though his rebellious streak emerged early, clashing with paternal authority.[6]Education and Formative Influences

Herman J. Mankiewicz attended Columbia University, where he majored in English and German.[17] He graduated in 1917 at age 19, demonstrating precocious academic ability fostered by his father's emphasis on intellectual achievement.[18][6] At Columbia, Mankiewicz engaged in extracurricular writing, contributing to the student newspaper Columbia Daily Spectator and the Varsity Show, activities that sharpened his satirical wit and narrative skills amid a curriculum rich in literary classics and linguistic analysis.[19] These experiences laid foundational influences for his later journalistic and dramatic pursuits, exposing him to rigorous debate and creative expression in an environment valuing erudition over convention.[17] Following graduation, Mankiewicz spent a year studying in Berlin, immersing himself in German literature, theater, and cabaret culture, which broadened his cosmopolitan perspective and attuned him to the interplay of politics, society, and storytelling.[20] This period, combined with Columbia's classical education, instilled a first-hand appreciation for European intellectual traditions that contrasted with American pragmatism, influencing his cynical yet incisive worldview evident in subsequent work.[2]Pre-Hollywood Career

Journalism and Reporting

Following his service in the United States Marines during World War I, Mankiewicz launched his journalism career in Europe, where he served as the Berlin correspondent for the Chicago Tribune from 1920 to 1922, covering the economic turmoil and political instability of post-war Germany under foreign editor James O'Donnell Bennett.[21] During this period, he also reported for Women's Wear Daily, providing dispatches on European fashion and cultural trends amid hyperinflation and social upheaval.[11] His firsthand observations of Germany's Weimar Republic, including the rise of extremist politics, informed his later writings and demonstrated his aptitude for sharp, on-the-ground analysis rather than rote wire service summaries.[22] Upon returning to New York in 1922, Mankiewicz joined The New York Times as assistant theater editor, a role that positioned him at the intersection of journalism and criticism during the Roaring Twenties' theatrical boom.[23] He contributed feature articles to Vanity Fair, including "On Being a Man" in June 1924, which satirized masculine pretensions through ironic first-person reflection, and "The Life of an Assistant Dramatic Editor" in March 1925, critiquing the grind of Broadway coverage and the commercialization of American drama.[24] These pieces showcased his wit and skepticism toward institutional pieties, traits honed in Berlin but adapted to domestic cultural reporting; he avoided the era's prevalent boosterism, instead favoring acerbic commentary on theatrical hype and journalistic routines.[25] Mankiewicz's reporting emphasized empirical detail over speculation, as seen in his Berlin work documenting currency devaluation—where a loaf of bread could cost billions of marks by 1923—and early signs of authoritarian resurgence, insights drawn from direct sourcing rather than secondary accounts.[26] By 1923, he had transitioned toward regular drama criticism, reviewing Broadway openings for The New York Times and contributing to The Saturday Evening Post, where his style prioritized causal analysis of production flaws, such as directorial overreach or script inconsistencies, over mere plot recaps.[1] This phase solidified his reputation among New York intellectuals, though his output remained sporadic due to personal indulgences; contemporaries noted his reluctance to file on deadline, preferring polished, contrarian prose.[27] His journalism thus bridged foreign affairs reporting with cultural critique, foreshadowing the narrative sophistication he later brought to screenwriting, before departing for Hollywood in 1926.[28]Publicity, Playwriting, and European Sojourns

Following his graduation from Columbia University in 1917 and brief wartime service, Mankiewicz married Sara Aaronson in April 1920 and soon relocated to Berlin, where he worked as a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune from 1920 to 1922, covering political and cultural developments amid the Weimar Republic's early instability.[21] During this European sojourn, he supplemented his income by serving as a publicist for the dancer Isadora Duncan, promoting her performances and persona in a period when she sought to revive her career in Europe after personal and professional setbacks.[29] Mankiewicz's dispatches from Berlin also included drama and book reviews submitted to The New York Times, reflecting his growing interest in theatrical criticism.[30] Returning to New York in 1922, Mankiewicz joined The New York Times as assistant drama editor, a position he held through 1926, during which he honed his wit through editing and contributing satirical pieces on Broadway productions.[30] In parallel, he ventured into playwriting, collaborating with George S. Kaufman on The Good Fellow, a three-act comedy that premiered at the Little Theatre on October 25, 1926, but closed after just seven performances due to poor reviews and audience disinterest.[31] The play's failure underscored the competitive Broadway landscape, yet Mankiewicz's involvement highlighted his early comedic flair, influenced by his journalistic background and associations with figures like Kaufman, though it yielded no financial success.[30] These efforts in publicity and playwriting bridged his European experiences with emerging opportunities in screenwriting, amid mounting personal debts from gambling and alcohol that strained his New York tenure.Personal Life

Marriage and Family Dynamics

Herman J. Mankiewicz married Shulamith Sara Aaronson, a Baltimore native born on September 7, 1897, on July 1, 1920.[2][32] The couple relocated briefly to Berlin, where Mankiewicz worked as a correspondent, before returning to the United States.[33] Their marriage endured for over three decades until Mankiewicz's death in 1953, marked by Sara's steadfast support amid his personal struggles.[32][34] The Mankiewiczes had three children: Johanna, Donald (known as Don, born 1922), and Francis (known as Frank).[1][34] Don pursued screenwriting, authoring works like I Want to Live! (1958), while Frank entered journalism and politics, serving as press secretary to Robert F. Kennedy and George McGovern.[34] Johanna's professional path is less documented in public records, though the family's intellectual bent—rooted in Mankiewicz's journalistic heritage—shaped their trajectories.[1] Family dynamics were strained by Mankiewicz's chronic alcoholism, compulsive gambling, and recurrent depressions, which Sara later described as "black depressions."[34] These habits led to financial instability and emotional volatility, with his brother Joseph observing that Mankiewicz wielded drinking and gambling to vent frustrations toward Sara, his father, and Hollywood figures like Louis B. Mayer.[14] Despite such tensions, Sara remained committed, providing stability as Mankiewicz's career oscillated between acclaim and self-sabotage; no records indicate separation or divorce, underscoring her role in sustaining the household through his excesses.[34] The children witnessed these patterns, yet channeled familial resilience into their own public endeavors, avoiding the full descent into Mankiewicz's vices.[34]Chronic Alcoholism and Gambling Habits

Mankiewicz exhibited chronic alcoholism from his early adulthood, a condition that progressively undermined his productivity and led to repeated professional dismissals in Hollywood. His excessive drinking, often conducted in social settings like poker games and parties, impaired his reliability as a screenwriter, contributing to his pattern of earning high fees only to squander them amid binges.[35] [2] This vice culminated in his death on March 5, 1953, at age 55 from uremic poisoning directly attributable to long-term alcohol abuse.[36] Interwoven with his alcoholism was a compulsive gambling habit that inflicted severe financial strain, with contemporaries estimating losses totaling around one million dollars over his lifetime through betting on horses, cards, and other wagers.[20] Specific incidents underscored the recklessness: in one case, he lost $1,000 on a coin toss, as detailed in Ben Hecht's autobiography.[37] In September 1939, while contracted to MGM, Mankiewicz sought an advance salary from studio head Louis B. Mayer after exhausting his earnings on gambling.[38] His wife, Sara Aaronson Mankiewicz, actively intervened against his drinking by diluting hidden liquor bottles to reduce his intake, though such measures proved insufficient against his entrenched patterns.[39] These parallel addictions fostered a cycle of fortune-building followed by dissipation, reinforcing his image among peers as a brilliant yet self-destructive figure whose vices mirrored the excesses of the era's creative class.[40] [1]Hollywood Career

Entry and Early Screenwriting

In April 1926, Herman J. Mankiewicz relocated from New York to Hollywood, where he was promptly employed by Paramount Pictures to write intertitles for silent films.[3] Shortly after arriving, he dispatched a telegram to fellow journalist and playwright Ben Hecht, famously stating: "Millions are to be grabbed out here and your only competition is idiots. Don't let this get around."[41] This message, which lured Hecht and other New York writers westward, reflected Mankiewicz's opportunistic view of the burgeoning film industry's demand for literate talent amid the transition from silents to sound.[33] Mankiewicz's initial contributions focused on intertitles, scripting captions for at least 25 silent features between mid-1926 and 1928, including Josef von Sternberg's The Last Command (1928).[3] His first story credit came earlier that year with The Road to Mandalay (1926), a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer production directed by Tod Browning and starring Lon Chaney as a one-eyed Singaporean criminal, adapted from a tale Mankiewicz co-developed with Elliott J. Clawson.[42] Other early Paramount efforts included the adaptation for Stranded in Paris (1926) and the screenplay for Fashions for Women (1927), directed by Dorothy Arzner, marking his shift toward narrative scripting as studios sought sophisticated dialogue for emerging talkies.[42] By 1927, Paramount elevated Mankiewicz to head of its scenario department, a position leveraging his journalistic wit and efficiency in overseeing script development during the chaotic silent-to-sound pivot.[3] In this role, he contributed titles and adaptations to films like A Gentleman of Paris (1927) and recruited East Coast talent, including Hecht, to professionalize screenwriting amid rapid production demands—Paramount released over 60 features annually by the late 1920s.[42] His early output emphasized concise, ironic prose suited to visual storytelling, foreshadowing the verbal precision that later defined his dialogue-heavy adaptations, though his personal excesses already strained studio relations.[41]Writing Style and Key Non-Kane Contributions

Mankiewicz's screenwriting was characterized by slick, satirical wit and a heavy reliance on sharp dialogue to drive narrative and character development, marking a shift toward more verbal, American-centric comedies in early Hollywood sound films.[43][44] This approach often infused scripts with cynical humor drawn from his journalistic background, prioritizing verbal sparring over visual spectacle and influencing the "script doctor" role where he refined others' work without formal credit.[11][45] Among his accredited contributions, Mankiewicz co-wrote the screenplay for Dinner at Eight (1933), adapting George S. Kaufman and Edna Ferber's play with Frances Marion into a pre-Code comedy-drama that showcased interwoven social satire through ensemble dialogue, earning praise for its incisive portrayal of upper-class pretensions amid economic turmoil.[46] He also penned the original screenplay for Man of the World (1931), a Paramount drama emphasizing moral ambiguity in expatriate cons and verbal intrigue.[47] Later, Mankiewicz received sole credit for The Pride of the Yankees (1942), a biographical sports film about Lou Gehrig that balanced inspirational elements with understated pathos through economical, dialogue-driven storytelling.[48][43] Uncredited, Mankiewicz frequently served as a script doctor, polishing drafts for high-profile productions; for instance, he contributed revisions to The Wizard of Oz (1939), enhancing character interactions and transitional scenes to support the film's fantastical elements with grounded wit.[49][43] Over his career, he worked on approximately 60 films in such capacities, often injecting satirical edge into studio assignments, though much of this labor went unrecognized due to the era's collaborative and hierarchical production norms.[6][11] One notable unproduced effort was The Mad Dog of Europe (1934), a prescient anti-Nazi satire he wrote while on leave from MGM, which Hollywood deemed too controversial for release amid rising political sensitivities.[11]The Citizen Kane Collaboration

In 1939, Orson Welles, who had been granted complete artistic control for his first feature film by RKO Pictures, recruited Herman J. Mankiewicz to co-write the screenplay for what would become Citizen Kane. Mankiewicz, leveraging his prior social interactions with newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst—including visits to Hearst's San Simeon estate—drew inspiration from Hearst's life to craft the character of Charles Foster Kane.[37][50] The collaboration began in earnest in early 1940, with Mankiewicz dictating an initial draft titled American over approximately six weeks, much of it from a hospital bed while recovering from a broken leg sustained in a car accident.[51][50] Welles extensively revised Mankiewicz's draft, incorporating non-linear narrative techniques, multiple flashbacks, and innovative structural elements that transformed the script into its final form.[37][52] Surviving script versions, including annotated drafts, demonstrate Welles's direct contributions to dialogue, scene rearrangements, and thematic depth, countering later assertions that Mankiewicz authored the screenplay independently.[53][54] Mankiewicz sought co-writing credit, leading to tensions; Welles initially preferred not to share on-screen credit but ultimately agreed, resulting in both receiving the 1941 Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay.[55][37] Posthumous claims by Mankiewicz's family and Pauline Kael's 1971 essay "Raising Kane" attributing sole authorship to Mankiewicz have been refuted by textual evidence from script revisions and contemporary accounts showing collaborative input.[54][53] Principal photography commenced in 1940 under Welles's direction, with Mankiewicz uninvolved in production beyond the script.[37] The film premiered on May 1, 1941, in New York City, earning critical acclaim for its technical innovations and storytelling but facing commercial challenges.[56] Hearst, perceiving the film as a libelous portrayal, orchestrated a suppression campaign through his media empire, banning advertisements, reviews, and mentions of Citizen Kane in his newspapers and pressuring theaters and the Hollywood establishment to withhold support.[56][57] Despite these efforts, the film secured nine Academy Award nominations, though it won only for the screenplay.[55]