Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Western (genre)

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2021) |

| Part of a series on |

| Westerns |

|---|

|

The Western is a genre of fiction typically set in the American frontier (commonly referred to as the "Old West" or the "Wild West") between the California Gold Rush of 1849 and the closing of the frontier in 1890. The genre is commonly associated with folk tales of the Western United States, particularly the Southwestern United States, as well as Northern Mexico and Western Canada.[1][2]: 7

The frontier is depicted in Western fiction as a sparsely populated, hostile region patrolled by cowboys, outlaws, sheriffs, and numerous other stock gunslinger characters. Western narratives often concern the gradual attempts to tame the crime-ridden American West using wider themes of justice, freedom, rugged individualism, manifest destiny, and the national history and identity of the United States. Native American populations were often portrayed as averse foes or savages.

Originating in vaquero heritage and Western fiction, the genre popularized the Western lifestyle, country-Western music, and Western wear globally.[3][4] Throughout the history of the genre, it has seen popular revivals and been incorporated into various subgenres.

Characteristics

[edit]Stories and characters

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2023) |

The classic Western is a morality drama, presenting the conflict between wilderness and civilization.[1] Stories commonly center on the life of a male drifter, cowboy, or gunslinger who rides a horse and is armed with a revolver or rifle. The male characters typically wear broad-brimmed and high-crowned Stetson hats,[5] neckerchief bandannas, vests, and cowboy boots with spurs. While many wear conventional shirts and trousers, alternatives include buckskins and dusters.

Women are generally cast in secondary roles as love interests for the male lead; or in supporting roles as saloon girls, prostitutes or as the wives of pioneers and settlers. The wife character often provides a measure of comic relief. Other recurring characters include Native Americans of various tribes described as Indians or Red Indians,[6] African Americans, Chinese Americans, Spaniards, Mexicans, law enforcement officers, bounty hunters, outlaws, bartenders, merchants, gamblers, soldiers (especially mounted cavalry), and settlers (farmers, ranchers, and townsfolk).

The ambience is usually punctuated with a Western music score, including American folk music and Spanish/Mexican folk music such as country, Native American music, New Mexico music, and rancheras.

| Literature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Oral literature | ||||||

| Major written forms | ||||||

|

||||||

| Prose genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Poetry genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Dramatic genres | ||||||

| History | ||||||

| Lists and outlines | ||||||

| Theory and criticism | ||||||

|

| ||||||

Locations

[edit]Westerns often stress the harshness of the wilderness and frequently set the action in an arid, desolate landscape of deserts and

mountains. Often, the vast landscape plays an important role, presenting a "mythic vision of the plains and deserts of the American West".[7] Specific settings include ranches, small frontier towns, saloons, railways, wilderness, and isolated military forts of the Wild West. Many Westerns use a stock plot of depicting a crime, then showing the pursuit of the wrongdoer, ending in revenge and retribution, which is often dispensed through a shootout or quick draw duel.[8][9][10]

Themes

[edit]

The Western genre sometimes portrays the conquest of the wilderness and the subordination of nature in the name of civilization or the confiscation of the territorial rights of the original, Native American, inhabitants of the frontier.[11] The Western depicts a society organized around codes of honor and personal, direct or private justice–"frontier justice"–dispensed by gunfights. These honor codes are often played out through depictions of feuds or individuals seeking personal revenge or retribution against someone who has wronged them (e.g., True Grit has revenge and retribution as its main themes). This Western depiction of personal justice contrasts sharply with justice systems organized around rationalistic, abstract law that exist in cities, in which social order is maintained predominantly through relatively impersonal institutions such as courtrooms. The popular perception of the Western is a story that centers on the life of a seminomadic wanderer, usually a cowboy or a gunfighter.[11] A showdown or duel at high noon featuring two or more gunfighters is a stereotypical scene in the popular conception of Westerns.[citation needed]

In some ways, such protagonists may be considered the literary descendants of the knights-errant, who stood at the center of earlier extensive genres such as the Arthurian romances.[11] Like the cowboy or gunfighter of the Western, the knight-errant of the earlier European tales and poetry was wandering from place to place on his horse, fighting villains of various kinds, and bound to no fixed social structures, but only to his own innate code of honor. Like knights-errant, the heroes of Westerns frequently rescue damsels in distress. Similarly, the wandering protagonists of Westerns share many characteristics with the ronin in modern Japanese culture.[citation needed]

The Western typically takes these elements and uses them to tell simple morality tales, although some notable examples (e.g. the later Westerns of John Ford or Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven, about an old contract killer) are more morally ambiguous. Westerns often stress the harshness and isolation of the wilderness, and frequently set the action in an arid, desolate landscape. Western films generally have specific settings, such as isolated ranches, Native American villages, or small frontier towns with a saloon. Oftentimes, these settings appear deserted and without much structure. Apart from the wilderness, the saloon usually emphasizes that this is the Wild West; it is the place to go for music (raucous piano playing), women (often prostitutes), gambling (draw poker or five-card stud), drinking (beer, whiskey, or tequila if set in Mexico), brawling, and shooting. In some Westerns, where civilization has arrived, the town has a church, a general store, a bank, and a school; in others, where frontier rules still hold sway, it is, as Sergio Leone said, "where life has no value".[citation needed]

Plots

[edit]Author and screenwriter Frank Gruber identified seven basic plots for Westerns:[12]

- Union Pacific story: The plot concerns construction of a railroad, a telegraph line, or some other type of modern technology on the wild frontier. Wagon-train stories fall into this category.

- Ranch story: Ranchers protecting their family ranch from rustlers or large landowners attempting to force out the proper owners.

- Empire story: The plot involves building a ranch empire or an oil empire from scratch, a classic rags-to-riches plot, often involving conflict over resources such as water or minerals.

- Revenge story: The plot often involves an elaborate chase and pursuit by a wronged individual, but it may also include elements of the classic mystery story.

- Cavalry and Indian story: The plot revolves around taming the wilderness for White settlers or fighting Native Americans.

- Outlaw story: The outlaw gangs dominate the action.

- Marshal story: The lawman and his challenges drive the plot.

Gruber noted that good writers use dialogue and plot development to expand these basic plots into believable stories.

Media

[edit]Film

[edit]

The American Film Institute defines Western films as those "set in the American West that [embody] the spirit, the struggle, and the demise of the new frontier".[13] Originally, these films were called "Wild West dramas", a reference to Wild West shows like Buffalo Bill Cody's.[14] The term "Western", used to describe a narrative film genre, appears to have originated with a July 1912 article in Motion Picture World magazine.[14]

Most of the characteristics of Western films were part of 19th-century popular Western fiction, and were firmly in place before film became a popular art form.[15][page needed] Western films commonly feature protagonists such as cowboys, gunslingers, and bounty hunters, who are often depicted as seminomadic wanderers who wear Stetson hats, bandannas, spurs, and buckskins, use revolvers or rifles as everyday tools of survival and as a means to settle disputes using frontier justice. Protagonists ride between dusty towns and cattle ranches on their trusty steeds.[16]

The first films that belong to the Western genre are a series of short single reel silents made in 1894 by Edison Studios at their Black Maria studio in West Orange, New Jersey. These featured veterans of Buffalo Bill's Wild West show exhibiting skills acquired by living in the Old West – they included Annie Oakley (shooting) and members of the Sioux (dancing).[17]

The earliest known Western narrative film is the British short Kidnapping by Indians, made by Mitchell and Kenyon in Blackburn, England, in 1899.[18][19] The Great Train Robbery (1903, based on the earlier British film A Daring Daylight Burglary), Edwin S. Porter's film starring Broncho Billy Anderson, is often erroneously cited as the first Western, though George N. Fenin and William K. Everson point out (as mentioned above) that the "Edison company had played with Western material for several years prior to The Great Train Robbery". Nonetheless, they concur that Porter's film "set the pattern—of crime, pursuit, and retribution—for the Western film as a genre".[20] The film's popularity opened the door for Anderson to become the screen's first Western star; he made several hundred Western film shorts. So popular was the genre that he soon faced competition from Tom Mix and William S. Hart.[21]

Western films were enormously popular in the silent film era (1894–1927). With the advent of sound in 1927–1928, the major Hollywood studios rapidly abandoned Westerns,[22] leaving the genre to smaller studios and producers. These smaller organizations churned out countless low-budget features and serials in the 1930s. An exception was The Big Trail, a 1930 American pre-Code Western early widescreen film shot on location across the American West starring 23-year-old John Wayne in his first leading role and directed by Raoul Walsh. The epic film noted for its authenticity was a financial failure due to Depression era theatres not willing to invest in widescreen technology. By the late 1930s, the Western film was widely regarded as a pulp genre in Hollywood, but its popularity was dramatically revived in 1939 by major studio productions such as Dodge City starring Errol Flynn, Jesse James with Tyrone Power, Union Pacific with Joel McCrea, Destry Rides Again featuring James Stewart and Marlene Dietrich, and especially John Ford's landmark Western adventure Stagecoach starring John Wayne, which became one of the biggest hits of the year. Released through United Artists, Stagecoach made John Wayne a mainstream screen star in the wake of a decade of headlining B Westerns. Wayne had been introduced to the screen 10 years earlier as the leading man in director Raoul Walsh's spectacular widescreen The Big Trail, which failed at the box office in spite of being shot on location across the American West, including the Grand Canyon, Yosemite, and the giant redwoods, due in part to exhibitors' inability to switch over to widescreen during the Great Depression. After renewed commercial successes in the late 1930s, the popularity of Westerns continued to rise until its peak in the 1950s, when the number of Western films produced outnumbered all other genres combined.[23]

The period from 1940 to 1960 has been called the "Golden Age of the Western".[24] It is epitomized by the work of several prominent directors including Robert Aldrich, Budd Boetticher, Delmer Daves, John Ford, and others. Some of the popular films during this era include Apache (1954), Broken Arrow (1950), and My Darling Clementine (1946).[25]

The changing popularity of the Western genre has influenced worldwide pop culture over time.[26][27] During the 1960s and 1970s, Spaghetti Westerns from Italy became popular worldwide; this was due to the success of Sergio Leone's storytelling method.[28][29] After having been previously pronounced dead, a resurgence of Westerns occurred during the 1990s with films such as Dances with Wolves (1990), Unforgiven (1992), and Geronimo (1993), as Westerns once again increased in popularity.[30][31]

Television

[edit]

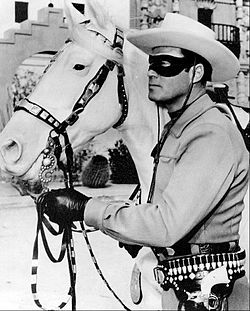

When television became popular in the late 1940s and 1950s, Television Westerns quickly became an audience favorite.[32][page needed] Beginning with rebroadcasts of existing films, a number of movie cowboys had their own TV shows. As demand for the Western increased, new stories and stars were introduced. A number of long-running TV Westerns became classics in their own right, such as: The Cisco Kid (1950-1956), The Lone Ranger (1949–1957), Death Valley Days (1952–1970), The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp (1955–1961), Cheyenne (1955–1962), Gunsmoke (1955–1975), Maverick (1957–1962), Have Gun – Will Travel (1957–1963), Wagon Train (1957–1965), The Rifleman (1958–1963), Rawhide (1959–1966), Bonanza (1959–1973), The Virginian (1962–1971), and The Big Valley (1965–1969). The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp was the first Western television series written for adults,[33] premiering four days before Gunsmoke on September 6, 1955.[34]: 570, 786 [35]: 351, 927

The peak year for television Westerns was 1959, with 26 such shows airing during primetime. At least six of them were connected in some extent to Wyatt Earp: The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, Tombstone Territory, Broken Arrow, Johnny Ringo, and Gunsmoke.[36] Increasing costs of American television production weeded out most action half-hour series in the early 1960s, and their replacement by hour-long television shows, increasingly in color.[37][page needed] Traditional Westerns died out in the late 1960s as a result of network changes in demographic targeting along with pressure from parental television groups. Future entries in the genre would incorporate elements from other genera, such as crime drama and mystery whodunit elements. Western shows from the 1970s included Hec Ramsey, Kung Fu, Little House on the Prairie, McCloud, The Life and Times of Grizzly Adams, and the short-lived but highly acclaimed How the West Was Won that originated from a miniseries with the same name. In the 1990s and 2000s, hour-long Westerns and slickly packaged made-for-TV movie Westerns were introduced, such as Lonesome Dove (1989) and Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman. Also, new elements were once again added to the Western formula, such as the space Western, Firefly, created by Joss Whedon in 2002. Deadwood was a critically acclaimed Western series that aired on HBO from 2004 through 2006. Hell on Wheels, a fictionalized story of the construction of the first transcontinental railroad, aired on AMC for five seasons between 2011 and 2016. Longmire is a Western series that centered on Walt Longmire, a sheriff in fictional Absaroka County, Wyoming. Originally aired on the A&E network from 2012 to 2014, it was picked up by Netflix in 2015 until the show's conclusion in 2017.

AMC and Vince Gilligan's critically acclaimed Breaking Bad is a much more modern take on the Western genre. Set in New Mexico, it follows Walter White (Bryan Cranston), a chemistry teacher diagnosed with Stage III Lung Cancer who cooks and sells crystal meth to provide money for his family after he dies, while slowly growing further and further into the illicit drug market, eventually turning into a ruthless drug dealer and killer. While the show has scenes in a populated suburban neighborhood and nearby Albuquerque, much of the show takes place in the desert, where Walter often takes his RV car out into the open desert to cook his meth, and most action sequences occur in the desert, similar to old-fashioned Western movies. The clash between the Wild West and modern technology like cars and cellphones, while also focusing primarily on being a crime drama makes the show a unique spin on both genres. Walter's reliance on the desert environment makes the Western-feel a pivotal role in the show, and would continue to be used in the spinoff series Better Call Saul.[38]

The neo-Western drama Yellowstone was streamed from 2018–2024.

Literature

[edit]Western fiction is a genre of literature set in the American Old West, most commonly between 1860 and 1900. The first critically recognized Western was The Virginian (1902) by Owen Wister.[39] Other well-known writers of Western fiction include Zane Grey, from the early 1900s, Ernest Haycox, Luke Short, and Louis L'Amour, from the mid 20th century. Many writers better known in other genres, such as Leigh Brackett, Elmore Leonard, and Larry McMurtry, have also written Western novels. The genre's popularity peaked in the 1960s, due in part to the shuttering of many pulp magazines, the popularity of televised Westerns, and the rise of the spy novel. Readership began to drop off in the mid- to late 1970s and reached a new low in the 2000s. Most bookstores, outside of a few Western states, now only carry a small number of Western novels and short-story collections.[40]

Literary forms that share similar themes include stories of the American frontier, the gaucho literature of Argentina, and tales of the settlement of the Australian Outback.

Visual arts

[edit]A number of visual artists focused their work on representations of the American Old West. American West-oriented art is sometimes referred to as "Western Art" by Americans. This relatively new category of art includes paintings, sculptures, and sometimes Native American crafts. Initially, subjects included exploration of the Western states and cowboy themes. Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell are two artists who captured the "Wild West" in paintings and sculpture.[41] After the death of Remington Richard Lorenz became the preeminent artist painting in the Western genre.[42]

Some art museums, such as the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Wyoming and the Autry National Center in Los Angeles, feature American Western Art.[43]

Anime and manga

[edit]With anime and manga, the genre tends towards the science-fiction Western – e.g., Cowboy Bebop (1998 anime), Trigun (1995–2007 manga), and Outlaw Star (1996–1999 manga). Although contemporary Westerns also appear, such as Koya no Shonen Isamu, a 1971 shonen manga about a boy with a Japanese father and a Native American mother, or El Cazador de la Bruja, a 2007 anime television series set in modern-day Mexico. Part 7 of the manga series JoJo's Bizarre Adventure is based in the American Western setting. The story follows racers in a transcontinental horse race, the "Steel Ball Run". Golden Kamuy (2014–2022) shifts its setting to the fallout of the Russo-Japanese War, specifically focusing on Hokkaido and Sakhalin, and featuring the Ainu people and other local tribes instead of Native Americans, as well other recognizable Western tropes.

Comics

[edit]Western comics have included serious entries, (such as the classic comics of the late 1940s and early 1950s (namely Kid Colt, Outlaw, Rawhide Kid, and Red Ryder) or more modern ones as Blueberry), cartoons, and parodies (such as Cocco Bill and Lucky Luke). In the 1990s and 2000s, Western comics leaned towards the fantasy, horror and science fiction genres, usually involving supernatural monsters, or Christian iconography as in Preacher. More traditional Western comics are found throughout this period, though (e.g., Jonah Hex and Loveless).

Video games

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2024) |

Video game Westerns emerged in the 1970s. These games drew on the imagery of a mythic West portrayed in stories, films, television shows, and other assorted Western-themed toys.[44]

When game developers went to the imaginary West to create new experiences, they often drew consciously or unconsciously from Western stories and films. The 1971 text-based, Mainframe computer game The Oregon Trail was first game to use the West as a setting, where it tasked players to lead a party of settlers moving westward in a covered wagon from Independence, Missouri to Oregon City, Oregon. The game only grew popular in the 1980s and 1990s as an educational game. The first video game Westerns to engage the mass public arrived in arcade games focused on the gunfighter in Westerns based on depictions in television shows, films and Electro-mechanical games such as Dale Six Shooter (1950), and Sega's Gun Fight (1970). The first of these games was Midway's Gun Fight, an adaptation of Taito's Western Gun (1975) which featured two players against each other in a duel set on a sparse desert landscape with a few cacti and a moving covered wagon to hide behind. Atari's Outlaw (1976) followed which explicitly framed the shootouts between "good guys" and "outlaws" also borrowing from gunfighter themes and imagery.[44] Early console games such as Outlaw (1978) for the Atari 2600 and Gun Fight (1978) for the Bally Astrocade were derivative of Midway's Gun Fight. These early video games featured limited graphical capabilities, which had developers create Westerns to the most easily recognizable and popular tropes of the gunfighter shootouts.[44]

Rockstar Games' Western-themed game Red Dead Redemption 2 (2018) had sold over 64 million copies by 2025, making it one of the best-selling video games of all time.[45]

Radio dramas

[edit]Western radio dramas were very popular from the 1930s to the 1960s. There were five types of Western radio dramas during this period: anthology programs, such as Empire Builders and Frontier Fighters; juvenile adventure programs such as Red Ryder and Hopalong Cassidy; legend and lore like Red Goose Indian Tales and Cowboy Tom's Round-Up; adult Westerns like Fort Laramie and Frontier Gentleman; and soap operas such as Cactus Kate.[46]: 8 Some popular shows include The Lone Ranger (first broadcast in 1933), The Cisco Kid (first broadcast in 1942), Dr. Sixgun (first broadcast in 1954), Have Gun–Will Travel (first broadcast in 1958), and Gunsmoke (first broadcast in 1952).[47] Many shows were done live, while others were transcribed.[46]: 9–10

Web series

[edit]Westerns have been showcased in short-episodic web series. Examples include League of STEAM, Red Bird, and Arkansas Traveler.

Subgenres

[edit]Within the larger scope of the Western genre, there are several recognized subgenres. Some subgenres, such as spaghetti Westerns, maintain standard Western settings and plots, while others take the Western theme and archetypes into different supergenres, such as neo-Westerns or space Westerns. For a time, Westerns made in countries other than the United States were often labeled by foods associated with the culture, such as spaghetti Westerns (Italy), meat pie Westerns (Australia), ramen Westerns (Asia), and masala Westerns (India).[48]

Influence on other genres

[edit]Being period drama pieces, both the Western and samurai genre influenced each other in style and themes throughout the years.[49] The Magnificent Seven was a remake of Akira Kurosawa's film Seven Samurai, and A Fistful of Dollars was a remake of Kurosawa's Yojimbo, which itself was inspired by Red Harvest, an American detective novel by Dashiell Hammett.[50] Kurosawa was influenced by American Westerns and was a fan of the genre, most especially John Ford.[51][52]

Despite the Cold War, the Western was a strong influence on Eastern Bloc cinema, which had its own take on the genre, the so-called Red Western or Ostern. Generally, these took two forms: either straight Westerns shot in the Eastern Bloc, or action films involving the Russian Revolution, the Russian Civil War, and the Basmachi rebellion.[53]

Many elements of space-travel series and films borrow extensively from the conventions of the Western genre. This is particularly the case in the space Western subgenre of science fiction. Peter Hyams's Outland transferred the plot of High Noon to Io, moon of Jupiter. More recently, the space opera series Firefly used an explicitly Western theme for its portrayal of frontier worlds. Anime shows such as Cowboy Bebop, Trigun and Outlaw Star have been similar mixes of science-fiction and Western elements. The science fiction Western can be seen as a subgenre of either Westerns or science fiction. Elements of Western films can be found also in some films belonging essentially to other genres. For example, Kelly's Heroes is a war film, but its action and characters are Western-like.

The character played by Humphrey Bogart in noir films such as Casablanca and To Have and Have Not—an individual bound only by his own private code of honor—has a lot in common with the classic Western hero. In turn, the Western has also explored noir elements, as with films such as Colorado Territory[54] and Pursued.[55][54]

In many of Robert A. Heinlein's books, the settlement of other planets is depicted in ways explicitly modeled on American settlement of the West. For example, in his Tunnel in the Sky, settlers set out to the planet New Canaan, via an interstellar teleporter portal across the galaxy, in Conestoga wagons, their captain sporting mustaches and a little goatee and riding a Palomino horse—with Heinlein explaining that the colonists would need to survive on their own for some years, so horses are more practical than machines.[56]

Stephen King's The Dark Tower is a series of seven books that meshes themes of Westerns, high fantasy, science fiction, and horror. The protagonist Roland Deschain is a gunslinger whose image and personality are largely inspired by the Man with No Name from Sergio Leone's films. In addition, the superhero fantasy genre has been described as having been derived from the cowboy hero, only powered up to omnipotence in a primarily urban setting.

The Western genre has been parodied on a number of occasions, famous examples being Support Your Local Sheriff!, Cat Ballou, Mel Brooks's Blazing Saddles, and Rustler's Rhapsody.[57]

George Lucas's Star Wars films use many elements of a Western, and Lucas has said he intended for Star Wars to revitalize cinematic mythology, a part the Western once held. The Jedi, who take their name from Jidaigeki, are modeled after samurai, showing the influence of Kurosawa. The character Han Solo dressed like an archetypal gunslinger, and the Mos Eisley cantina is much like an Old West saloon.[58]

Meanwhile, films such as The Big Lebowski, which plucked actor Sam Elliott out of the Old West and into a Los Angeles bowling alley, and Midnight Cowboy, about a Southern-boy-turned-gigolo in New York (who disappoints a client when he does not measure up to Gary Cooper), transplanted Western themes into modern settings for both purposes of parody and homage.[59]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Rubin, Joan Shelley; Casper, Scott E., eds. (2013). The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Cultural and Intellectual History. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. p. 557. ISBN 978-0-19-976435-8.

- ^ Carter, Matthew (2014). Myth of the Western: New Perspectives on Hollywood's Frontier Narrative. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748685592.

- ^ "Vaqueros: The First Cowboys of the Open Range". History. August 15, 2003. Archived from the original on March 17, 2023. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- ^ Fraser, Kristopher (February 14, 2023). "Cowboy Core Fashion Is Trending: Beyoncé, Harry Styles & More Create Buzz Around Western-inspired Looks". WWD. Archived from the original on March 29, 2023. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- ^ Edgerton, Gary R. (September 13, 2013). Westerns: The Essential 'Journal of Popular Film and Television' Collection. Routledge. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-135-76508-8.

- ^ Butts, Dennis (2004). "Shaping boyhood: British Empire builders and adventurers". In Hunt, Peter (ed.). International Companion Encyclopedia of Children's Literature. Vol. 1 (Second ed.). Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. pp. 340–351. ISBN 0-203-32566-4.

By the 1840s, of course, adults were already reading tales of adventure involving Red Indians

- ^ Cowie, Peter (2004). John Ford and the American West. New York: Harry Abrams Inc. ISBN 978-0-8109-4976-8.

- ^ Agnew, Jeremy. December 2, 2014. The Creation of the Cowboy Hero: Fiction, Film and Fact, p. 88, McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7839-2

- ^ Adams, Cecil (June 25, 2004). "Did Western gunfighters really face off one-on-one?". Straight Dope. Archived from the original on August 18, 2020. Retrieved October 4, 2014. June 25, 2004

- ^ "Wild Bill Hickok fights first western showdown". History.com. July 21, 2014. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c Newman, Kim (1990). Wild West Movies. Bloomsbury.

- ^ Gruber, Frank The Pulp Jungle Sherbourne Press, 1967

- ^ "America's 10 Greatest Films in 10 Classic Genres". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on September 30, 2018. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ a b McMahan, Alison. Alice Guy Blaché: Lost Visionary of the Cinema. Continuum. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-5013-4023-9.

- ^ Smith, Henry Nash (1970). Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth. Harvard University Press.

- ^ Indick, William (November 21, 2014). The Psychology of the Western: How the American Psyche Plays Out on Screen. McFarland. pp. 8, 12. ISBN 978-0-7864-9211-4.

[T]he principal archetype of the genre, the Western hero, is analyzed within the context of his various personas: the chivalrous cowboy, the honorable marshal, the lone crusader, and the rebel outlaw... He is more comfortable living in the open frontier than in the cities, and most importantly, he does not conform to the laws and customs of civilized society. He answers only to his own code of honor and enforces his own personal brand of justice... [W]riters established the cowboy hero as the legendary icon of the West. They dressed him in chaps and a ten-gallon hat, straddled him atop a horse, armed him with a revolver, and set him loose on the Western plains.

- ^ "Sioux ghost dance". Library of Congress. 1894. Archived from the original on January 22, 2022. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- ^ "World's first Western movie 'filmed in Blackburn'". BBC News. October 31, 2019. Archived from the original on January 22, 2023. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ "Kidnapping by Indians". BFI. Archived from the original on January 22, 2023. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ Fenin, George N.; Everson, William K. (1962). The Western: From Silents to Cinerama. New York City: Bonanza Books. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-163-70021-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "Bronco Billy Anderson Is Dead at 88". The New York Times. January 21, 1971. Archived from the original on October 15, 2019. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ New York Times Magazine (November 10, 2007).

- ^ Indick, William (September 10, 2008). Indick, William. The Psychology of the Western. Pg. 2 McFarland, Aug 27, 2008. McFarland. ISBN 9780786434602. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ Gittell, Noah (June 17, 2014). "Superheroes Replaced Cowboys at the Movies. But It's Time to Go Back to Cowboys". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on July 21, 2022. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Grey, Zane; Brand, Max; Mulford, Clarence E.; Raine, William MacLeod; Bower, B. M. (September 28, 2020). Essential Western Novels - Volume 10. Tacet Books. ISBN 978-3-96987-750-0.

- ^ "Why Are Westerns Still Popular?". Netflix Tudum. December 27, 2021. Archived from the original on March 15, 2023. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ Calhoun, Jordan (December 15, 2022). "Why Everyone Suddenly Loves Westerns Again". Men's Health. Archived from the original on March 15, 2023. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ Butler, Nancy (January 27, 2023). "Inventing America: Spaghetti Westerns and Sergio Leone". Italy Segreta. Archived from the original on March 15, 2023. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ Gray, Tim (January 4, 2019). "Sergio Leone's Spaghetti Westerns Made a Fistful of Dollars and Clint Eastwood a Star". Variety. Archived from the original on March 15, 2023. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ Busby, Mark; Buscombe, Edward; Pearson, Roberta E. (1999). "Back in the Saddle Again: New Essays on the Western". The Western Historical Quarterly. 30 (4). Oxford University Press (OUP): 520. doi:10.2307/971437. ISSN 0043-3810. JSTOR 971437.

- ^ Kollin, Susan (1999). "Theorizing the Western". Western American Literature. 34 (2). Project Muse: 238–250. doi:10.1353/wal.1999.0081. ISSN 1948-7142. S2CID 166137254.

- ^ Yoggy, Gary A. (1995). Riding the Video Range: The Rise and Fall of the Western on Television. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0021-8.

- ^ Burris, Joe (May 10, 2005). "The Eastern Earps". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on December 16, 2018. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Brooks, Tim; Marsh, Earle F. (2007). The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows, 1946-Present. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-49773-4. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ McNeil, Alex (1996). Total Television: the Comprehensive Guide to Programming from 1948 to the Present. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-02-4916-8. Archived from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ Guinn, Jeff (May 15, 2012). The Last Gunfight: The Real Story of the Shootout at the O.K. Corral-And How It Changed the American West. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-5425-0.

- ^ Kisseloff, Jeff (1995). The Box: An Oral History of Television, 1920-1961. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-86470-6.

- ^ "Local IQ - Contemporary Western: An interview with Vince Gilligan". April 3, 2013. Archived from the original on April 3, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2022.

- ^ "Classic Wild West Literature". June 27, 2017.

- ^ McVeigh, Stephen (2007). The American Western. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748629442.

- ^ Buscombe, Edward (1984). "Painting the Legend: Frederic Remington and the Western". Cinema Journal. pp. 12–27.

- ^ Wisconsin : a guide to the Badger State. New York: Duell, Sloan Pearce. 1941. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-60354-048-3. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Goetzmann, William H. (1986). The West of the Imagination. New York: Norton. ISBN 9780393023701.

- ^ a b c Saucier, Jeremy (July 3, 2024). "Gunfighter Gaming: A History of the Video Game Western Part I (1971 to 1979)". The Strong. Archived from the original on July 13, 2024. Retrieved October 22, 2024.

- ^ Sirani, Jordan (February 18, 2025). "The 10 Best-Selling Video Games of All Time". IGN. Retrieved July 23, 2025.

- ^ a b French, Jack; Siegel, David S. (November 14, 2013). Radio Rides the Range: A Reference Guide to Western Drama on the Air, 1929-1967. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7146-1.

- ^ "Old Time Radio Westerns". otrwesterns.com. Archived from the original on March 19, 2011.

- ^ Groves, Derham (October 28, 2022). Australian Westerns in the Fifties: Kangaroo, Hopalong Cassidy on Tour, and Whiplash. Springer Nature. pp. xii. ISBN 978-3-031-12883-7. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- ^ "Cowboys and Shoguns: The American Western, Japanese Jidaigeki, and Cross-Cultural Exchange". Digitalcommons.uri.edu. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (January 23, 2007). "New DVDs: 'Films of Kenneth Anger' and 'Samurai Classics'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 6, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ Crogan, Patrick. "Translating Kurosawa". Senses of Cinema. Archived from the original on October 3, 2009.

- ^ Shaw, Justine. "Star Wars Origins". Far Cry from the Original Site. Archived from the original on November 3, 2015. Retrieved December 20, 2015. December 14, 2015

- ^ Miller, Cynthia J.; Riper, A. Bowdoin Van (November 21, 2013). International Westerns: Re-Locating the Frontier. Scarecrow Press. pp. 379–384. ISBN 978-0-8108-9288-0.

- ^ a b Meuel, David (January 28, 2015). The Noir Western: Darkness on the Range, 1943-1962. McFarland. pp. 39, 45–46. ISBN 978-1-4766-1974-3.

- ^ Schwartz, Ronald (November 5, 2013). Houses of Noir: Dark Visions from Thirteen Film Studios. McFarland. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-4766-0460-2.

- ^ Heinlein, Robert A. (March 15, 2005). Tunnel in the Sky. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-0551-8.

- ^ O'Connor, John E.; Rollins, Peter (November 11, 2005). Hollywood's West: The American Frontier in Film, Television, and History. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 218–230. ISBN 978-0-8131-2354-7.

- ^ Wickman, Forrest (December 13, 2015). "Star Wars Is a Postmodern Masterpiece". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ Silva, Robert (2009). "Future of the Classic". Not From 'Round Here... Cowboys Who Pop Up Outside the Old West. Archived from the original on December 13, 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Buscombe, Edward, and Christopher Brookeman. The BFI Companion to the Western (A. Deutsch, 1988)

- Everson, William K. A Pictorial History of the Western Film (New York: Citadel Press, 1969)

- Kitses, Jim. Horizons West: The Western from John Ford to Clint Eastwood (British Film Institute, 2007).

- Lenihan, John H. Showdown: Confronting Modern America in the Western Film (University of Illinois Press, 1980)

- Nachbar, John G. Focus on the Western (Prentice Hall, 1974)

- Simmon, Scott. The Invention of the Western Film: A Cultural History of the Genre's First Half Century (Cambridge University Press, 2003)

External links

[edit]- Articles on Western film and TV in Western American Literature

- Special issue of Western American Literature on Global Westerns

- Most Popular Westerns at the Internet Movie Database

- Western Writers of America website

- "The Western", St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture, 2002

- I Watch Westerns, Ludwig von Mises Institute

- Film Festival for the Western Genre website

- Western Filmscript Collection. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Western (genre)

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins in Folklore, Literature, and Early Cinema (19th-Early 20th Century)

The roots of the Western genre trace to 19th-century American folklore and popular literature, which romanticized the frontier experience amid westward expansion following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and the California Gold Rush starting in 1848. Dime novels, popularized by Erastus Beadle's Beadle's Dime Novels series launched in 1860, featured sensational tales of cowboys, outlaws, and stagecoach holdups, drawing from real events like train robberies and Indian wars to craft myths of rugged individualism and heroic gunfights. These inexpensive paperbacks, selling for ten cents each, reached millions and established archetypal elements such as the lone cowboy confronting lawlessness, influencing public perceptions of the West as a testing ground for moral resolve despite their often exaggerated depictions of violence and adventure.[13] By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, literary works refined these motifs into more structured narratives. Owen Wister's The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains, published in 1902, is widely regarded as the first true Western novel, portraying a stoic Wyoming cowboy enforcing justice against rustlers and embodying virtues of chivalry and self-reliance; it became a bestseller with over 200,000 copies sold in its first year and set the template for the honorable gunslinger protagonist. Zane Grey's Riders of the Purple Sage, released in 1912, further solidified the genre by depicting a Utah rancher's struggle against Mormon rustlers, emphasizing vast landscapes and personal vendettas; Grey's vivid descriptions of the Southwest sold millions and inspired numerous adaptations, marking a shift toward formulaic plots of pursuit and redemption. These novels built on folklore's oral traditions of cowboy ballads and tall tales, privileging empirical accounts of cattle drives and frontier justice over idealized Eastern views.[14][15] Early cinema adapted these literary origins into visual storytelling, with Edison Manufacturing Company's short films like Cripple Creek Bar-Room Scene (1899) capturing saloon brawls and frontier life. The genre's breakthrough came with Edwin S. Porter's The Great Train Robbery in 1903, a 12-minute silent film produced by Edison, which dramatized a bandit gang's assault on a train, a posse's pursuit, and a climactic shootout, incorporating cross-cutting editing techniques that advanced narrative film structure; viewed by audiences nationwide, it grossed over $100,000 and popularized Western tropes of robbery and revenge. Subsequent one-reelers from 1904–1910, such as Selig Polyscope's The Life of a Cowboy (1906), depicted ranching and Indian skirmishes, bridging dime novel sensationalism to screen while relying on New Jersey and New York locations to simulate the West, thus establishing cinema as a medium for visualizing folklore-derived myths of expansionist heroism.[16]Golden Age of American Westerns (1930s-1950s)

The Golden Age of American Westerns, spanning the 1930s to the 1950s, saw the genre dominate Hollywood output through low-budget "B" pictures and elevated prestige productions. Between 1930 and 1954, studios released approximately 2,700 Western films, many as double-feature fillers programmed for weekly matinees targeting young audiences.[17] These B-Westerns emphasized formulaic plots of ranchers battling outlaws or rustlers, often featuring singing cowboys who integrated musical performances into narratives. Gene Autry, dubbed the "Singing Cowboy," starred in dozens of such films for Republic Pictures starting in 1935, blending Western action with country music that appealed to Depression-era escapism.[18] Roy Rogers followed suit from 1938, appearing in about 85 B-Westerns through 1951, frequently with his horse Trigger and wife Dale Evans, achieving massive popularity via Republic's Trucolor process for postwar entries.[19] A pivotal shift occurred in 1939 with John Ford's Stagecoach, which transformed the Western from marginal entertainment to serious cinema. Shot on location in Monument Valley, the film starred John Wayne in his breakthrough role as the Ringo Kid, a fugitive escorting a stagecoach through Apache territory, and grossed over $1 million domestically while earning two Academy Awards, including Ford's for Best Director.[20] This success revitalized the genre by emphasizing character depth, ensemble dynamics, and epic landscapes over serial-like simplicity, influencing directors like Howard Hawks and Raoul Walsh. Postwar A-Westerns proliferated, with Ford's My Darling Clementine (1946) depicting the Wyatt Earp legend and Wagon Master (1950) exploring Mormon pioneers, while Wayne anchored hits like Red River (1948), a cattle-drive saga that highlighted father-son conflict and earned three Oscar nominations. The 1950s brought psychological depth and moral ambiguity to Westerns, reflecting Cold War anxieties. Films like Fred Zinnemann's High Noon (1952), starring Gary Cooper as a marshal facing abandonment by townsfolk, critiqued community cowardice and won four Oscars, including Best Actor. George Stevens' Shane (1953) portrayed a gunslinger mediating homesteaders versus cattle barons, grossing $20 million worldwide and cementing Alan Ladd's heroic archetype. Meanwhile, television's rise fragmented the audience; by mid-decade, adult-oriented series supplanted juvenile B-Westerns, with Gunsmoke debuting in 1955 as a gritty Dodge City drama starring James Arness as Marshal Matt Dillon.[21] Running until 1975, Gunsmoke prioritized realistic violence and ethical dilemmas, drawing 40 million weekly viewers at its peak and signaling the genre's migration from screens to living rooms, which diminished theatrical Western production by the late 1950s.[22]Spaghetti and Revisionist Westerns (1960s-1970s)

Spaghetti Westerns, a subgenre of Western films primarily produced in Italy and Spain during the 1960s and 1970s, emerged as low-budget alternatives to declining Hollywood productions, often filmed in the Tabernas Desert of Spain to mimic American landscapes.[23] The term "Spaghetti Western" was coined by American critics to denote their Italian origins, reflecting a pejorative nod to pasta rather than artistic merit, though the films featured darker tones, graphic violence, and anti-hero protagonists that contrasted with the moral clarity of earlier American Westerns.[24] Over 500 such films were made, with Sergio Leone's works setting the template through stylistic innovations like extreme close-ups, wide landscapes, and Ennio Morricone's twangy, operatic scores.[23] Leone's A Fistful of Dollars (1964), released in Italy on September 12, 1964, and in the United States on January 18, 1967, launched the trend with a production budget of approximately $200,000–$225,000, starring American television actor Clint Eastwood as a nameless drifter exploiting rival gangs for profit.[25] Uncredited as a loose remake of Akira Kurosawa's Yojimbo (1961), it grossed around $14.5 million internationally despite legal disputes with Kurosawa's team, which delayed U.S. distribution and cost producers a settlement equivalent to 15% of profits plus Yojimbo's original budget.[26] This success spawned Leone's Dollars Trilogy, including For a Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), which amplified themes of greed, betrayal, and amoral survival amid Civil War chaos, grossing cumulatively over $25 million worldwide and elevating Eastwood to stardom while reviving interest in the Western amid Hollywood's genre fatigue.[27] These Italian imports influenced American revisionist Westerns, which deconstructed frontier myths by portraying violence as brutal and consequential rather than heroic, reflecting 1960s–1970s disillusionment with authority amid the Vietnam War and civil rights struggles.[28] Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch (1969), released on June 18, 1969, epitomized this shift with its slow-motion balletic gunfights and aging outlaws facing obsolescence in 1913 Mexico, using multi-camera editing to depict over 300 squibs of blood in the finale, pushing boundaries post-Hays Code decline.[29] Budgeted at $3.2 million, it earned $50.7 million worldwide despite initial controversy over its "nihilistic" tone, influencing subsequent films by emphasizing flawed, doomed protagonists and the inexorable advance of modernity over individualism.[30] Other examples, like Arthur Penn's Little Big Man (1970), further critiqued historical narratives by humanizing Native Americans and exposing cavalry brutality, contributing to a cycle of over 100 revisionist entries that prioritized historical realism and moral ambiguity over romanticized heroism.[31]Decline, Neo-Westerns, and Recent Revivals (1980s-2025)

The Western genre experienced a marked decline in theatrical production during the 1980s, with major studios producing far fewer films compared to the 1970s peak of dozens annually, dropping to single digits in some years due to escalating production costs and shifting audience preferences toward science fiction and action genres.[32][10] A pivotal event was the 1980 release of Heaven's Gate, directed by Michael Cimino, which ballooned from an initial $11.6 million budget to over $44 million amid overruns and reshoots, grossing only $3.5 million domestically and prompting United Artists' near-collapse while deterring investment in ambitious Western epics.[33][34] Despite this, isolated commercial successes emerged, such as Clint Eastwood's Pale Rider (1985), which grossed $41.4 million on a $6.9 million budget, making it the decade's top-earning Western but insufficient to reverse the trend of genre fatigue and competition from blockbusters like E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.[35][36] Amid the downturn, neo-Westerns began to emerge as a subgenre, transplanting traditional Western motifs—such as isolated frontiers, moral ambiguity, and lone protagonists confronting lawlessness—into contemporary American settings, often emphasizing gritty realism over romanticized heroism.[37] Early examples include the Coen Brothers' Blood Simple (1984), a Texas-set noir-thriller involving betrayal and violence in rural isolation, which prefigured the subgenre's blend of crime elements with Western archetypes.[38] This approach continued into the 1990s and 2000s with films like Fargo (1996) and No Country for Old Men (2007), the latter adapting Cormac McCarthy's novel to depict a drug deal gone wrong in 1980s West Texas, featuring a relentless antagonist evoking gunslinger tropes amid failing institutional justice. Neo-Westerns appealed by addressing modern dilemmas like economic decay and ethical relativism without the historical constraints of classic Westerns, sustaining interest through independent and prestige productions.[37] A tentative theatrical revival materialized in the early 1990s with Unforgiven (1992), directed by and starring Clint Eastwood, which deconstructed genre myths of heroic violence through an aging gunslinger's reluctant return to killing, earning $159 million worldwide and four Academy Awards, including Best Picture.[39] However, sustained momentum shifted to television in the 2000s and 2010s, where serialized formats allowed deeper exploration of frontier dynamics in modern contexts; HBO's Deadwood (2004–2006) portrayed a lawless 1870s mining camp with complex antiheroes, while FX's Justified (2010–2015) updated marshal archetypes to contemporary Kentucky via U.S. Marshal Raylan Givens.[6] Netflix's Godless (2017) and A&E's Longmire (2012–2017) further diversified with female-led and reservation-based narratives, respectively, broadening appeal amid declining big-screen output. The 2010s and early 2020s saw robust revivals in both film and television, driven by high-profile adaptations and original stories capitalizing on neo-Western grit. Films like The Revenant (2015), directed by Alejandro G. Iñárritu, grossed $532 million globally by emphasizing survival in 1820s wilderness, and Hell or High Water (2016) earned Oscar nominations for its depiction of rural Texas bank robberies amid economic hardship.[40] Paramount Network's Yellowstone (2018–2024), created by Taylor Sheridan, achieved massive viewership, with its season 5 premiere drawing 15.7 million live-plus-same-day viewers in 2022—the highest-rated cable episode that year—and the series finale reaching 11.4 million in December 2024, spawning prequels like 1883 (2021) and 1923 (2022–2023) that extended family ranch conflicts into historical frames.[41][42] By 2025, ongoing series such as the returning 1923 season 2 and Hulu's American Primeval continued this cable and streaming surge, reflecting renewed interest in themes of land, legacy, and individualism adapted to prestige television's narrative depth.[43]Defining Characteristics

Settings and Environments

The Western genre is primarily set in the American Old West, encompassing the frontier territories and states of the southwestern and central United States during the late 19th century, roughly from the post-Civil War era of the 1860s to the closing of the frontier in 1890 as declared by the U.S. Census Bureau.[44] This temporal framework aligns with historical expansion westward following the California Gold Rush of 1849 and the transcontinental railroad's completion in 1869, which facilitated settlement but also intensified conflicts over land and resources.[44] Geographically, narratives center on arid deserts, expansive prairies of the Great Plains, and mountainous regions in areas like Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and the Rocky Mountains, where environmental harshness—marked by scarce water, extreme temperatures, and vast open spaces—serves as a literal and metaphorical backdrop for human struggle and isolation.[45][1] Key environments include remote ranches, frontier outposts, and nascent boomtowns characterized by wooden boardwalks, saloons, general stores, and sheriff's offices along a single main street, often evoking the transient nature of settlements like those in historical cattle trail hubs such as Dodge City, Kansas, or Tombstone, Arizona.[46] Railroads, stagecoach routes, and river crossings frequently appear as conduits of progress and peril, symbolizing the encroachment of civilization into untamed wilderness, as seen in depictions of cattle drives along trails like the Chisholm Trail, which transported over 5 million longhorn cattle from Texas to railheads between 1867 and 1884.[44] The desolate quality of these landscapes underscores the genre's emphasis on self-reliance, with natural features like canyons, mesas, and buttes not only providing dramatic vistas but also practical elements for ambushes, pursuits, and standoffs, reflecting the real logistical challenges of frontier life where distances between habitations could exceed 100 miles.[1][46] While core settings remain tied to the American West, variations extend to border regions in northern Mexico for tales involving cross-cultural clashes or pursuits, as in stories of Apache raids or bandit incursions during the 1870s-1880s, though these maintain the dominant arid, unforgiving terrain to preserve thematic consistency.[45] In literature predating cinema, such as Owen Wister's The Virginian (1902), environments similarly prioritize the Wyoming Territory's open ranges and isolation to explore ranching economies and vigilante justice, establishing a template for visual media where the land itself acts as an active antagonist, testing characters' endurance amid historical events like the Johnson County War of 1892.[47] This environmental realism draws from documented frontier conditions, including annual precipitation as low as 10 inches in desert zones, which amplified risks from dust storms, flash floods, and wildlife, thereby grounding the genre's portrayal of moral and physical trials in verifiable ecological constraints.[48][47]Archetypal Characters and Roles

In Western films, the protagonist typically embodies the archetype of the rugged individualist—a skilled gunslinger, cowboy, or lawman who enforces justice through personal prowess and moral resolve rather than reliance on communal institutions. This figure, often stoic and self-reliant, arrives in a disordered frontier town to confront chaos, as analyzed in genre studies where the hero represents frontier values of independence and direct action.[49] Exemplified by Gary Cooper's Marshal Will Kane in High Noon (1952), the hero faces isolation from cowardly townsfolk, underscoring themes of personal responsibility over collective dependence.[50] The antagonist counterpart is the villainous outlaw, bandit leader, or corrupt cattle baron who embodies greed, lawlessness, and threats to emerging order. These characters, such as ruthless gang bosses in films like The Searchers (1956), drive conflict by exploiting weakness in nascent communities, reflecting historical tensions over land and authority in the American West.[51] Villains often command henchmen, amplifying their menace through organized predation, a trope rooted in dime novel traditions adapted to cinema.[52] Supporting the hero is the sidekick, a loyal companion providing comic relief, practical aid, or moral counterpoint, prevalent in B-Westerns of the 1930s–1950s. Actors like George "Gabby" Hayes portrayed these verbose, elderly figures who humanize the hero's solitude without overshadowing his agency, as noted in historical accounts of the genre's serial productions.[53] The sidekick archetype contrasts the hero's taciturnity, injecting humor through folksy wisdom or bungling, yet remains subordinate to maintain narrative focus on individualism. Female roles frequently feature the love interest—a resilient settler woman or saloon singer symbolizing civilization's domestic anchor—whose presence motivates the hero's commitment to taming the wilderness. In classic examples, such as Maureen O'Hara's characters opposite John Wayne, women embody tradition and community, balancing the hero's transient freedom with calls for settlement.[50] Secondary archetypes include the wise preacher or doctor, offering ethical guidance or healing, and the town drunk, representing failed adaptation to frontier rigors; these stock figures, drawn from eight core types like the gambler or tycoon, populate ensemble narratives to depict societal cross-sections.[54]| Archetype | Key Traits | Exemplary Portrayals |

|---|---|---|

| Hero | Stoic, gun-skilled individualist | Gary Cooper in High Noon (1952)[50] |

| Villain | Greedy outlaw or corrupt authority | John Vernon types in revisionist works, rooted in classics[51] |

| Sidekick | Comic, loyal supporter | Gabby Hayes in Republic serials[53] |

| Love Interest | Domestic symbol of order | Maureen O'Hara in John Ford films[50] |