Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Alcoholism

View on Wikipedia

| Alcoholism | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Alcohol addiction, alcohol dependence syndrome, alcohol use disorder (AUD)[1] |

| |

| A French temperance organisation poster depicting the effects of alcoholism in a family, c. 1915: "Ah! When will we be rid of alcohol?" | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology, toxicology, addiction medicine |

| Symptoms | Drinking large amounts of alcohol over a long period, difficulty cutting down, acquiring and drinking alcohol taking up a lot of time, usage resulting in problems, withdrawal occurring when stopping[2] |

| Complications | Mental illness, delirium, Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome, irregular heartbeat, cirrhosis of the liver, cancer, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, suicide[3][4][5][6] |

| Duration | Long term[2] |

| Causes | Environmental and genetic factors[4] |

| Risk factors | Stress, anxiety, easy access[4][7] |

| Diagnostic method | Questionnaires, blood tests[4] |

| Treatment | Alcohol cessation typically with benzodiazepines, counselling, acamprosate, disulfiram, naltrexone[8][9][10] Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and other Twelve Step Programs, AA/Twelve Step Facilitation (AA/TSF)[11] |

| Frequency | As of 2015, globally, 8.6% of people had or currently have an alcohol use disorder (AUD), and 2.2% had an AUD in the past 12 months[12] |

| Deaths | In 2012, globally, 3.3 million deaths or 5.9% of all deaths were due to alcohol[13] |

Alcoholism is the continued drinking of alcohol despite it causing problems. Some definitions require evidence of dependence and withdrawal.[14] Problematic alcohol use has been mentioned in the earliest historical records. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated there were 283 million people with alcohol use disorders worldwide as of 2016[update].[15][16] The term alcoholism was first coined in 1852,[17] but alcoholism and alcoholic are considered stigmatizing and likely to discourage seeking treatment, so diagnostic terms such as alcohol use disorder and alcohol dependence are often used instead in a clinical context.[18][19][20] Other terms, some slurs and some informal, have been used to refer to people affected by alcoholism such as tippler, sot, drunk, drunkard, dipsomaniac and souse.[21]

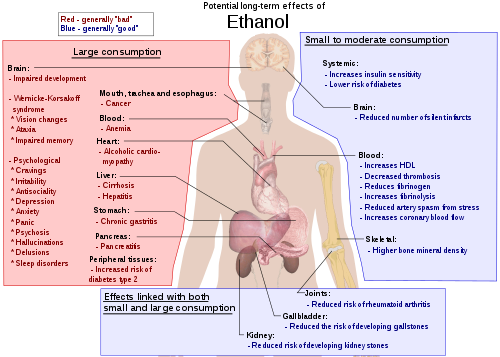

Alcohol is addictive, and heavy long-term use results in many negative health and social consequences. It can damage all organ systems, but especially affects the brain, heart, liver, pancreas, and immune system.[4][5] Heavy usage can result in trouble sleeping, and severe cognitive issues like dementia, brain damage, or Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome. Physical effects include irregular heartbeat, impaired immune response, cirrhosis, increased cancer risk, and severe withdrawal symptoms if stopped suddenly.[4][5][22]

These effects can reduce life expectancy by 10 years.[23] Drinking during pregnancy may harm the child's health,[3] and drunk driving increases the risk of traffic accidents. Alcoholism is associated with violent and non-violent crime.[24] While alcoholism directly resulted in 139,000 deaths worldwide in 2013,[25] in 2012 3.3 million deaths may be attributable globally to alcohol.[13]

The development of alcoholism is attributed to environment and genetics equally.[4] Someone with a parent or sibling with an alcohol use disorder is 3-4 times more likely to develop alcohol use disorder, but only a minority do.[4] Environmental factors include social, cultural and behavioral influences.[26] High stress levels and anxiety, as well as alcohol's low cost and easy accessibility, increase the risk.[4][7] Medically, alcoholism is considered both a physical and mental illness.[27][28] Questionnaires are usually used to detect possible alcoholism.[4][29] Further information is then collected to confirm the diagnosis.[4]

Treatment takes several forms.[9] Due to medical problems that can occur during withdrawal, alcohol cessation should often be controlled carefully.[9] A common method involves the use of benzodiazepine medications.[9] The medications acamprosate or disulfiram may also be used to help prevent further drinking.[10] Mental illness or other addictions may complicate treatment.[30] Individual, group therapy, or support groups are used to attempt to keep a person from returning to alcoholism.[8][31] Among them is the abstinence-based mutual aid fellowship Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). A 2020 scientific review found clinical interventions encouraging increased participation in AA (AA/twelve step facilitation (TSF))—resulted in higher abstinence rates over other clinical interventions, and most studies found AA/TSF led to lower health costs.[a][33][34][35]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]The risk of alcohol dependence begins at low levels of drinking and increases directly with both the volume of alcohol consumed and a pattern of drinking larger amounts on an occasion, to the point of intoxication, which is sometimes called binge drinking. Binge drinking is the most common pattern of alcoholism. It has different definitions and one of this defines it as a pattern of drinking when a male has five or more drinks on an occasion or a female has at least four drinks on an occasion.[36]

Long-term misuse

[edit]

Alcoholism is characterized by an increased tolerance to alcohol – which means that an individual can consume more alcohol – and physical dependence on alcohol, which makes it hard for an individual to control their consumption. The physical dependency caused by alcohol can lead to an affected individual having a very strong urge to drink alcohol. These characteristics play a role in decreasing the ability to stop drinking of an individual with an alcohol use disorder.[37] Alcoholism can have adverse effects on mental health, contributing to psychiatric disorders and increasing the risk of suicide. A depressed mood is a common symptom of heavy alcohol drinkers.[38][39]

Warning signs

[edit]Warning signs of alcoholism include the consumption of increasing amounts of alcohol and frequent intoxication, preoccupation with drinking to the exclusion of other activities, promises to quit drinking and failure to keep those promises, the inability to remember what was said or done while drinking (colloquially known as "blackouts"), personality changes associated with drinking, denial or the making of excuses for drinking, the refusal to admit excessive drinking, dysfunction or other problems at work or school, the loss of interest in personal appearance or hygiene, marital and economic problems, and other symptoms such as loss of appetite, respiratory infections, or increased anxiety.[40]

Physical

[edit]Short-term effects

[edit]Drinking enough to cause a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.03–0.12% typically causes an overall improvement in mood and possible euphoria (intense feelings of well-being and happiness), increased self-confidence and sociability,[41] decreased anxiety,[42] impaired judgment and fine muscle coordination. A BAC of 0.09% to 0.25% causes lethargy, sedation, balance problems and blurred vision. A BAC of 0.18% to 0.30% causes profound confusion, impaired speech (e.g. slurred speech), staggering, and vomiting. A BAC from 0.25% to 0.40% causes stupor, unconsciousness, amnesia, vomiting (death may occur due to inhalation of vomit while unconscious) and respiratory depression (potentially life-threatening). A BAC from 0.35% to 0.80% causes a coma (unconsciousness), life-threatening respiratory depression and possibly fatal alcohol poisoning.[41][43][42] With all alcoholic beverages, drinking while driving, operating an aircraft or heavy machinery increases the risk of an accident; virtually all countries have penalties for drunk driving.[44]

Long-term effects

[edit]In 2023, the World Health Organization stated that no level of alcohol consumption is safe, and even low or moderate consumption may cause harms to someone's health, including an increased risk of many cancers.[45] Having more than one drink a day for women or two drinks for men increases the risk of heart disease, high blood pressure, atrial fibrillation, and stroke.[46] Risk is greater with binge drinking, which may also result in violence or accidents. Globally, about 3.3 million deaths (5.9% of all deaths) are believed to be due to alcohol each year.[13] Alcoholism reduces a person's life expectancy by around ten years[23] and alcohol use is the third leading cause of early death in the United States.[46] Long-term alcohol misuse can cause a number of physical symptoms, including cirrhosis of the liver, pancreatitis, epilepsy, polyneuropathy, alcoholic dementia, heart disease, nutritional deficiencies, peptic ulcers[47] and sexual dysfunction, and can eventually be fatal. Other physical effects include an increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease, malabsorption, alcoholic liver disease, and several cancers such as breast cancer and head and neck cancer.[48] Damage to the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system can occur from sustained alcohol consumption.[49][50] A wide range of immunologic defects can result and there may be a generalized skeletal fragility, in addition to a recognized tendency to accidental injury, resulting in a propensity for bone fractures.[51]

Women develop long-term complications of alcohol dependence more rapidly than do men; women also have a higher mortality rate from alcoholism than men.[52] Examples of long-term complications include brain, heart, and liver damage[53] and an increased risk of breast cancer. Additionally, heavy drinking over time has been found to have a negative effect on reproductive functioning in women. This results in reproductive dysfunction such as anovulation, decreased ovarian mass, problems or irregularity of the menstrual cycle, and early menopause.[52] Alcoholic ketoacidosis can occur in individuals who chronically misuse alcohol and have a recent history of binge drinking.[54][55] The amount of alcohol that can be biologically processed and its effects differ between sexes. Equal dosages of alcohol consumed by men and women generally result in women having higher blood alcohol concentrations (BACs), since women generally have a lower weight and higher percentage of body fat and therefore a lower volume of distribution for alcohol than men.[56]

Psychiatric

[edit]Long-term misuse of alcohol can cause a wide range of mental health problems. Severe cognitive problems are common; approximately 10% of all dementia cases are related to alcohol consumption, making it the second leading cause of dementia.[57] Excessive alcohol use causes damage to brain function, and psychological health can be increasingly affected over time.[58] Social skills are significantly impaired in people with alcoholism due to the neurotoxic effects of alcohol on the brain, especially the prefrontal cortex area of the brain. The social skills that are impaired by alcohol use disorder include impairments in perceiving facial emotions, prosody, perception problems, and theory of mind deficits; the ability to understand humor is also impaired in people who misuse alcohol.[59] Psychiatric disorders are common in people with alcohol use disorders, with as many as 25% also having severe psychiatric disturbances. The most prevalent psychiatric symptoms are anxiety and depression disorders. Psychiatric symptoms usually initially worsen during alcohol withdrawal, but typically improve or disappear with continued abstinence.[60] Psychosis, confusion, and organic brain syndrome may be caused by alcohol misuse, which can lead to a misdiagnosis such as schizophrenia.[61] Panic disorder can develop or worsen as a direct result of long-term alcohol misuse.[62][63]

The co-occurrence of major depressive disorder and alcoholism is well documented.[64][65][66] Among those with comorbid occurrences, a distinction is commonly made between depressive episodes that remit with alcohol abstinence ("substance-induced"), and depressive episodes that are primary and do not remit with abstinence ("independent" episodes).[67][68][69] Additional use of other drugs may increase the risk of depression.[70] Psychiatric disorders differ depending on gender. Women who have alcohol-use disorders often have a co-occurring psychiatric diagnosis such as major depression, anxiety, panic disorder, bulimia, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or borderline personality disorder. Men with alcohol-use disorders more often have a co-occurring diagnosis of narcissistic or antisocial personality disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, impulse disorders or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).[71] Women with alcohol use disorder are more likely to experience physical or sexual assault, abuse, and domestic violence than women in the general population,[71] which can lead to higher instances of psychiatric disorders and greater dependence on alcohol.[72]

Social effects

[edit]Serious social problems arise from alcohol use disorder due to the pathological changes in the brain and the intoxicating effects of alcohol.[57][73] Alcohol misuse is associated with an increased risk of committing criminal offences, including child abuse, domestic violence, rape, burglary and assault.[74] Alcoholism is associated with loss of employment,[75] which can lead to financial problems. Drinking at inappropriate times and behavior caused by reduced judgment can lead to legal consequences, such as criminal charges for drunk driving[76] or public disorder, or civil penalties for tortious behavior. An alcoholic's behavior and mental impairment while drunk can profoundly affect those surrounding the user and lead to isolation from family and friends. This isolation can lead to marital conflict and divorce, or contribute to domestic violence. Alcoholism can also lead to child neglect, with subsequent lasting damage to the emotional development of children of people with alcohol use disorders.[77] For this reason, children of people with alcohol use disorders can develop a number of emotional problems. For example, they can become afraid of their parents, because of their unstable mood behaviors. They may develop shame over their inadequacy to liberate their parents from alcoholism and, as a result of this, may develop self-image problems, which can lead to depression.[78]

Alcohol withdrawal

[edit]

As with similar substances with a sedative-hypnotic mechanism, such as barbiturates and benzodiazepines, withdrawal from alcohol dependence can be fatal if it is not properly managed.[73][79] Alcohol's primary effect is the increase in stimulation of the GABAA receptor, promoting central nervous system depression. With repeated heavy consumption of alcohol, these receptors are desensitized and reduced in number, resulting in tolerance and physical dependence. When alcohol consumption is stopped too abruptly, the person's nervous system experiences uncontrolled synapse firing. This can result in symptoms that include anxiety, upset stomach or nausea,[80] life-threatening seizures, delirium tremens, hallucinations, shakes and possible heart failure.[81][82] Other neurotransmitter systems are also involved, especially dopamine, NMDA and glutamate.[37][83]

Severe acute withdrawal symptoms such as delirium tremens and seizures rarely occur after 1-week post cessation of alcohol. The acute withdrawal phase can be defined as lasting between one and three weeks. In the period of 3–6 weeks following cessation, anxiety, depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbance are common.[84] Similar post-acute withdrawal symptoms have also been observed in animal models of alcohol dependence and withdrawal.[85]

A kindling effect also occurs in people with alcohol use disorders whereby each subsequent withdrawal syndrome is more severe than the previous withdrawal episode; this is due to neuroadaptations which occur as a result of periods of abstinence followed by re-exposure to alcohol. Individuals who have had multiple withdrawal episodes are more likely to develop seizures and experience more severe anxiety during withdrawal from alcohol than alcohol-dependent individuals without a history of past alcohol withdrawal episodes. The kindling effect leads to persistent functional changes in brain neural circuits as well as to gene expression.[86] Kindling also results in the intensification of psychological symptoms of alcohol withdrawal.[84] There are decision tools and questionnaires that help guide physicians in evaluating alcohol withdrawal. For example, the CIWA-Ar objectifies alcohol withdrawal symptoms in order to guide therapy decisions which allows for an efficient interview while at the same time retaining clinical usefulness, validity, and reliability, ensuring proper care for withdrawal patients, who can be in danger of death.[87]

Causes

[edit]

A complex combination of genetic and environmental factors influences the risk of the development of alcoholism.[88] Genes that influence the metabolism of alcohol also influence the risk of alcoholism, as can a family history of alcoholism.[89] There is compelling evidence that alcohol use at an early age may influence the expression of genes which increase the risk of alcohol dependence. These genetic and epigenetic results are regarded as consistent with large longitudinal population studies finding that the younger the age of drinking onset, the greater the prevalence of lifetime alcohol dependence.[90][91]

Severe childhood trauma is also associated with a general increase in the risk of drug dependency.[88] Lack of peer and family support is associated with an increased risk of alcoholism developing.[88] Genetics and adolescence are associated with an increased sensitivity to the neurotoxic effects of chronic alcohol misuse. Cortical degeneration due to the neurotoxic effects increases impulsive behaviour, which may contribute to the development, persistence and severity of alcohol use disorders. There is evidence that with abstinence, there is a reversal of at least some of the alcohol induced central nervous system damage.[92] The use of cannabis was associated with later problems with alcohol use.[93] Alcohol use was associated with an increased probability of later use of tobacco and illegal drugs such as cannabis.[94]

Availability

[edit]Alcohol is the most available, widely consumed, and widely misused recreational drug. Beer alone is the world's most widely consumed[95] alcoholic beverage; it is the third-most popular drink overall, after water and tea.[96] It is thought by some to be the oldest fermented beverage.[97][98][99][100]

Gender difference

[edit]Based on combined data in the US from SAMHSA's 2004–2005 National Surveys on Drug Use & Health, the rate of past-year alcohol dependence or misuse among persons aged 12 or older varied by level of alcohol use: 44.7% of past month heavy drinkers, 18.5% binge drinkers, 3.8% past month non-binge drinkers, and 1.3% of those who did not drink alcohol in the past month met the criteria for alcohol dependence or misuse in the past year. Males had higher rates than females for all measures of drinking in the past month: any alcohol use (57.5% vs. 45%), binge drinking (30.8% vs. 15.1%), and heavy alcohol use (10.5% vs. 3.3%), and males were twice as likely as females to have met the criteria for alcohol dependence or misuse in the past year (10.5% vs. 5.1%).[101] However, because females generally weigh less than males, have more fat and less water in their bodies, and metabolize less alcohol in their esophagus and stomach, they are likely to develop higher blood alcohol levels per drink. Women may also be more vulnerable to liver disease.[102]

Genetic variation

[edit]There are genetic variations that affect the risk for alcoholism.[89][88][103][104] Some of these variations are more common in individuals with ancestry from certain areas; for example, Africa, East Asia, the Middle East and Europe. The variants with strongest effect are in genes that encode the main enzymes of alcohol metabolism, ADH1B and ALDH2.[89][103][104] These genetic factors influence the rate at which alcohol and its initial metabolic product, acetaldehyde, are metabolized.[89] They are found at different frequencies in people from different parts of the world.[105][89][106] The alcohol dehydrogenase allele ADH1B*2 causes a more rapid metabolism of alcohol to acetaldehyde, and reduces risk for alcoholism;[89] it is most common in individuals from East Asia and the Middle East. The alcohol dehydrogenase allele ADH1B*3 also causes a more rapid metabolism of alcohol. The allele ADH1B*3 is only found in some individuals of African descent and certain Native American tribes. African Americans and Native Americans with this allele have a reduced risk of developing alcoholism.[89][106][107] Native Americans, however, have a significantly higher rate of alcoholism than average; risk factors such as cultural environmental effects (e.g. trauma) have been proposed to explain the higher rates.[108][109] The aldehyde dehydrogenase allele ALDH2*2 greatly reduces the rate at which acetaldehyde, the initial product of alcohol metabolism, is removed by conversion to acetate; it greatly reduces the risk for alcoholism.[89][105]

A genome-wide association study (GWAS) of more than 100,000 human individuals identified variants of the gene KLB, which encodes the transmembrane protein β-Klotho, as highly associated with alcohol consumption. The protein β-Klotho is an essential element in cell surface receptors for hormones involved in modulation of appetites for simple sugars and alcohol.[110] Several large GWAS have found differences in the genetics of alcohol consumption and alcohol dependence, although the two are to some degree related.[103][104][111]

DNA damage

[edit]Alcohol-induced DNA damage, when not properly repaired, may have a key role in the neurotoxicity induced by alcohol.[112] Metabolic conversion of ethanol to acetaldehyde can occur in the brain and the neurotoxic effects of ethanol appear to be associated with acetaldehyde induced DNA damages including DNA adducts and crosslinks.[112] In addition to acetaldehyde, alcohol metabolism produces potentially genotoxic reactive oxygen species, which have been demonstrated to cause oxidative DNA damage.[112]

Diagnosis

[edit]Definition

[edit]

Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word alcoholism, it is not a recognized diagnosis, and the use of the term alcoholism is discouraged due to its heavily stigmatized connotations.[18][19] It is classified as alcohol use disorder[2] in the DSM-5[4] or alcohol dependence in the ICD-11.[113] In 1979, the World Health Organization discouraged the use of alcoholism due to its inexact meaning, preferring alcohol dependence syndrome.[114]

Misuse, problem use, abuse, and heavy use of alcohol refer to improper use of alcohol, which may cause physical, social, or moral harm to the drinker.[115] The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, issued by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) in 2005, defines "moderate use" as no more than two alcoholic beverages a day for men and no more than one alcoholic beverage a day for women.[116] The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) defines binge drinking as the amount of alcohol leading to a blood alcohol content (BAC) of 0.08, which, for most adults, would be reached by consuming five drinks for men or four for women over a two-hour period. According to the NIAAA, men may be at risk for alcohol-related problems if their alcohol consumption exceeds 14 standard drinks per week or 4 drinks per day, and women may be at risk if they have more than 7 standard drinks per week or 3 drinks per day. It defines a standard drink as one 12-ounce bottle of beer, one 5-ounce glass of wine, or 1.5 ounces of distilled spirits.[117] Despite this risk, a 2014 report in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that only 10% of either "heavy drinkers" or "binge drinkers" defined according to the above criteria also met the criteria for alcohol dependence, while only 1.3% of non-binge drinkers met the criteria. An inference drawn from this study is that evidence-based policy strategies and clinical preventive services may effectively reduce binge drinking without requiring addiction treatment in most cases.[118]

Alcoholism

[edit]The term alcoholism is commonly used amongst laypeople, but the word is poorly defined. Despite the imprecision inherent in the term, there have been attempts to define how the word alcoholism should be interpreted when encountered. In 1992, it was defined by the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (NCADD) and ASAM as "a primary, chronic disease characterized by impaired control over drinking, preoccupation with the drug alcohol, use of alcohol despite adverse consequences, and distortions in thinking."[119] MeSH has had an entry for alcoholism since 1999, and references the 1992 definition.[120]

The WHO calls alcoholism "a term of long-standing use and variable meaning", and use of the term was disfavored by a 1979 WHO expert committee.[121]

In professional and research contexts, the term alcoholism is not currently favored, but rather alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, or alcohol use disorder are used.[4][2] Talbot (1989) observes that alcoholism in the classical disease model follows a progressive course: if people continue to drink, their condition will worsen. This will lead to harmful consequences in their lives, physically, mentally, emotionally, and socially.[122] Johnson (1980) proposed that the emotional progression of the addicted people's response to alcohol has four phases. The first two are considered "normal" drinking and the last two are viewed as "typical" alcoholic drinking.[122]

DSM and ICD

[edit]In the United States, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is the most common diagnostic guide for mental disorders,[123] whereas most countries use the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) for administrative and diagnostic purposes.[124] The two manuals use similar but not identical nomenclature to classify alcohol problems.

| Manual | Nomenclature | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| DSM-IV | Alcohol abuse, or Alcohol dependence |

|

| DSM-5 | Alcohol use disorder | "A problematic pattern of alcohol use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by [two or more symptoms out of a total of 12], occurring within a 12-month period ...."[129] |

| ICD-10 | Alcohol harmful use, or Alcohol dependence syndrome | Definitions are similar to that of the DSM-IV. The World Health Organization uses the term "alcohol dependence syndrome" rather than alcoholism.[114] The concept of "harmful use" (as opposed to "abuse") was introduced in 1992's ICD-10 to minimize underreporting of damage in the absence of dependence.[126] The term "alcoholism" was removed from ICD between ICD-8/ICDA-8 and ICD-9.[130] |

| ICD-11 | Episode of harmful use of alcohol, Harmful pattern of use of alcohol, or Alcohol dependence |

|

Social barriers

[edit]Attitudes and social stereotypes can create barriers to the detection and treatment of alcohol use disorder. This is more of a barrier for women than men.[why?] Fear of stigmatization may lead women to deny that they have a medical condition, to hide their drinking, and to drink alone. This pattern, in turn, leads family, physicians, and others to be less likely to suspect that a woman they know has alcohol use disorder.[52] In contrast, reduced fear of stigma may lead men to admit that they are having a medical condition, to display their drinking publicly, and to drink in groups. This pattern, in turn, leads family, physicians, and others to be more likely to suspect that a man they know is someone with an alcohol use disorder.[71]

Screening

[edit]Screening for alcohol misuse is recommended among those over the age of 18, the screening interval is not well established.[134][135][136] Some national organizations recommend screening adolescents 12 years and older.[137] Several tools may be used to detect a loss of control of alcohol use. These tools are mostly self-reports in questionnaire form. Another common theme is a score or tally that sums up the general severity of alcohol use.[138] Online questionnaires or on paper have greater sensitivity for identifying unhealthy alcohol use compared to in person questions asked by a healthcare worker.[136]

The CAGE questionnaire, named for its four questions, is one such example that may be used to screen patients quickly in a doctor's office.

Two "yes" responses indicate that the respondent should be investigated further.

The questionnaire asks the following questions:

- The CAGE questionnaire has demonstrated a high effectiveness in detecting alcohol-related problems; however, it has limitations in people with less severe alcohol-related problems, white women and college students.[141]

Other tests are sometimes used for the detection of alcohol dependence, such as the Alcohol Dependence Data Questionnaire, which is a more sensitive diagnostic test than the CAGE questionnaire. It helps distinguish a diagnosis of alcohol dependence from one of heavy alcohol use.[142] The Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (MAST) is a screening tool for alcoholism widely used by courts to determine the appropriate sentencing for people convicted of alcohol-related offenses,[143] driving under the influence being the most common. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), a screening questionnaire developed by the World Health Organization, is unique in that it has been validated in six countries and is used internationally. Like the CAGE questionnaire, it uses a simple set of questions – a high score requiring a deeper investigation.[144] The AUDIT questionnaire has a sensitivity of 73-100% for detecting unhealthy alcohol use, however the specificity is low.[136] The Paddington Alcohol Test (PAT) was designed to screen for alcohol-related problems amongst those attending Accident and Emergency departments. It concords well with the AUDIT questionnaire but is administered in a fifth of the time.[145]

Urine and blood tests

[edit]Alcohol use is generally measured by self-reporting, but in clinical settings biomarkers are recommended. Various biological markers are used to assess chronic or recent use of alcohol, one common test being that of blood alcohol content (BAC).[146] Monitoring levels of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) is sometimes used to assess continued alcohol intake. But levels of GGT are elevated in only half of men with alcohol use disorder, and it is less commonly elevated in women and younger people.[147] GGT levels remain persistently elevated for many weeks with continued drinking, with a half life of 2–3 weeks, making the GGT level a useful assessment of continued and chronic alcohol use.[147] However, elevated levels of GGT may also be seen in non-alcohol related liver diseases, diabetes, obesity or overweight, heart failure, hyperthyroidism and some medications.[147] Phosphatidylethanol (PEth) is a biomarker that is present in the red blood cells for several weeks after drinking, with its levels grossly corresponding to amount of alcohol consumed, and a detection limit as long as 5 weeks, making it a useful test to assess continued alcohol use.[147] Phosphatidylethanol is considered to have a high specificity, which means that a negative test result is very likely to mean the subject is not alcohol dependent.[148][149] Studies have consistently measured PEth specificity of 100%.[149]

Ethyl glucuronide may be measured to assess recent alcohol intake, with levels being detected in urine up to 48 hours after alcohol intake. However, it is a poor measure of the amount of alcohol consumed.[147] Measurement of ethanol levels in the blood, urine and breath are also used to assess recent alcohol intake, often in the emergency setting.[147]

Other laboratory markers of chronic alcohol misuse include:[150]

- Macrocytosis (enlarged MCV)

- Moderate elevation of AST and ALT and an AST: ALT ratio of 2:1

- High carbohydrate deficient transferrin (CDT)

Electrolyte and acid-base abnormalities including hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hyponatremia, hyperuricemia, metabolic acidosis, and respiratory alkalosis are common in people with alcohol use disorders.[5]

Alcohol use monitoring (both by self report or by biomarkers) is very important to the success of treatment of alcohol misuse. However, the cost of biomarkers and the intrusiveness of constant monitoring may limit their utility.[148]

Prevention

[edit]The World Health Organization, the European Union and other regional bodies, national governments and parliaments have formed alcohol policies in order to reduce the harm of alcoholism.[151][152]

Increasing the age at which alcohol can be purchased, and banning or restricting alcohol beverage advertising are common methods to reduce alcohol use among adolescents and young adults in particular, see Alcoholism in adolescence. Another common method of alcoholism prevention is taxation of alcohol products – increasing price of alcohol by 10% is linked with reduction of consumption of up to 10%.[153]

Credible, evidence-based educational campaigns in the mass media about the consequences of alcohol misuse have been recommended. Guidelines for parents to prevent alcohol misuse amongst adolescents, and for helping young people with mental health problems have also been suggested.[154]

Because alcohol is often used for self-medication of conditions like anxiety temporarily, prevention of alcoholism may be attempted by reducing the severity or prevalence of stress and anxiety in individuals.[4][7]

Management

[edit]Treatments are varied because there are multiple perspectives of alcoholism. Those who approach alcoholism as a medical condition or disease recommend differing treatments from, for instance, those who approach the condition as one of social choice. Most treatments focus on helping people discontinue their alcohol intake, followed up with life training and/or social support to help them resist a return to alcohol use. Since alcoholism involves multiple factors which encourage a person to continue drinking, they must all be addressed to successfully prevent a relapse. An example of this kind of treatment is detoxification followed by a combination of supportive therapy, attendance at self-help groups, and ongoing development of coping mechanisms. Much of the treatment community for alcoholism supports an abstinence-based zero tolerance approach popularized by the 12 step program of Alcoholics Anonymous; however, some prefer a harm-reduction approach.[155]

Cessation of alcohol intake

[edit]Medical treatment for alcohol detoxification usually involves administration of a benzodiazepine, in order to ameliorate alcohol withdrawal syndrome's adverse impact.[156][157] The addition of phenobarbital improves outcomes if benzodiazepine administration lacks the usual efficacy, and phenobarbital alone might be an effective treatment.[158] Propofol also might enhance treatment for individuals showing limited therapeutic response to a benzodiazepine.[159][160] Individuals who are only at risk of mild to moderate withdrawal symptoms can be treated as outpatients. Individuals at risk of a severe withdrawal syndrome as well as those who have significant or acute comorbid conditions can be treated as inpatients. Direct treatment can be followed by a treatment program for alcohol dependence or alcohol use disorder to attempt to reduce the risk of relapse.[9] Experiences following alcohol withdrawal, such as depressed mood and anxiety, can take weeks or months to abate while other symptoms persist longer due to persisting neuroadaptations.[84]

Psychological

[edit]

Various forms of group therapy or psychotherapy are sometimes used to encourage and support abstinence from alcohol, or to reduce alcohol consumption to levels that are not associated with adverse outcomes. Mutual-aid group-counseling is an approach used to facilitate relapse prevention.[8] Alcoholics Anonymous was one of the earliest organizations formed to provide mutual peer support and non-professional counseling, however the effectiveness of Alcoholics Anonymous is disputed.[161] A 2020 Cochrane review concluded that Twelve-Step Facilitation (TSF) probably achieves outcomes such as fewer drinks per drinking day, however evidence for such a conclusion comes from low to moderate certainty evidence "so should be regarded with caution".[162] Others include LifeRing Secular Recovery, SMART Recovery, Women for Sobriety, and Secular Organizations for Sobriety.[163]

Manualized[164] Twelve Step Facilitation (TSF) interventions (i.e. therapy which encourages active, long-term Alcoholics Anonymous participation) for Alcohol Use Disorder lead to higher abstinence rates, compared to other clinical interventions and to wait-list control groups.[165]

Moderate drinking

[edit]Moderate drinking amongst people with alcohol dependence—often termed controlled drinking—has been subject to significant controversy.[166] Indeed, much of the skepticism toward the viability of moderate drinking goals stems from historical ideas about alcoholism, now replaced with alcohol use disorder or alcohol dependence in most scientific contexts. A 2021 meta-analysis and systematic review of interventions designed to promote moderate (controlled) drinking found that this treatment model demonstrated a non-inferior outcome compared to an abstinence-oriented approach for many people with alcohol problems.[167][b]

Mutual support programs such as Moderation Management and DrinkWise do not mandate complete abstinence. While most people with severe alcohol use disorders are unable to limit their drinking, individuals with mild to moderate alcohol problems are often able to limit the quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption such that their drinking does not cause harm to themselves or others. A 2002 US study by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) showed that 17.7% of individuals diagnosed as alcohol dependent more than one year prior returned to low-risk drinking. This group, however, showed fewer initial symptoms of dependency.[168]

A follow-up study, using the same subjects that were judged to be in remission in 2001–2002, examined the rates of return to problem drinking in 2004–2005. The study found abstinence from alcohol was the most stable form of remission for recovering alcoholics.[169] There was also a 1973 study showing chronic alcoholics drinking moderately again,[170] but a 1982 follow-up showed that 95% of subjects were not able to maintain drinking in moderation over the long term.[171][172] Another study was a long-term (60 year) follow-up of two groups of alcoholic men which concluded that "return to controlled drinking rarely persisted for much more than a decade without relapse or evolution into abstinence."[173] Internet based measures appear to be useful at least in the short term.[174]

Medications

[edit]In the United States there are four approved medications for alcoholism: acamprosate, two methods of using naltrexone and disulfiram.[175]

- Acamprosate may stabilise the brain chemistry that is altered due to alcohol dependence via antagonising the actions of glutamate, a neurotransmitter which is hyperactive in the post-withdrawal phase.[176] By reducing excessive NMDA activity which occurs at the onset of alcohol withdrawal, acamprosate can reduce or prevent alcohol withdrawal related neurotoxicity.[177] Acamprosate reduces the risk of relapse amongst alcohol-dependent persons.[178][179] Acamprosate is not recommended in those with advanced, decompensated liver cirrhosis due to the risk of liver toxicity.[147] It may be taken by those with milder liver disease. And it also cannot be taken by those with severe kidney disease.[136]

- Naltrexone is a competitive antagonist for opioid receptors, effectively blocking the effects of endorphins and opioids. Naltrexone may be given as a daily oral tablet or as a monthly intramuscular injection.[147] Naltrexone is used to decrease cravings for alcohol and encourage abstinence. Alcohol causes the body to release endorphins, which in turn release dopamine and activate the reward pathways; hence in the body Naltrexone reduces the pleasurable effects from consuming alcohol.[180] Evidence supports a reduced risk of relapse among alcohol-dependent persons and a decrease in excessive drinking.[179] Naltrexone should not be used in those with advanced liver disease or those with acute hepatitis due to the risk of liver toxicity.[147] Naltrexone should also not be used in those who take opiates as it can precipitate an opiate withdrawal.[136] The once monthly intramuscular injectable naltrexone was found to be slightly more effective in some studies, leading to 5 less drinking days per month compared to the oral form.[136] Nalmefene also appears effective and works in a similar manner.[179]

- Disulfiram prevents the elimination of acetaldehyde by inhibiting the enzyme acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. Acetaldehyde is a chemical the body produces when breaking down ethanol. Acetaldehyde itself is the cause of many hangover symptoms from alcohol use. The overall effect is acute discomfort when alcohol is ingested characterized by flushing, nausea, a rapid heart rate and low blood pressure.[147] Disulfiram should not be used in those with advanced liver disease due to the risk of life-threatening liver toxicity.[147] The evidence of effectiveness of disulfiram in the treatment of alcohol misuse is limited.[136]

Several other drugs are also used and many are under investigation.[181]

- Benzodiazepines are a first line medication in the management of acute alcohol withdrawal, however their use outside of the acute withdrawal period is not recommended.[147] Benzodiazepines with a shorter half life, such as lorazepam or oxazepam are preferred in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal as their shorter half lives and less active metabolites have a lower risk of confusion in those with liver disease.[147] If used long-term, they can cause a worse outcome in alcoholism. Alcoholics on chronic benzodiazepines have a lower rate of achieving abstinence from alcohol than those not taking benzodiazepines. Initiating prescriptions of benzodiazepines or sedative-hypnotics in individuals in recovery has a high rate of relapse with one author reporting more than a quarter of people relapsed after being prescribed sedative-hypnotics. Those who are long-term users of benzodiazepines should not be withdrawn rapidly, as severe anxiety and panic may develop, which are known risk factors for alcohol use disorder relapse. Taper regimes of 6–12 months have been found to be the most successful, with reduced intensity of withdrawal.[182][183]

- Calcium carbimide works in the same way as disulfiram; it has an advantage in that the occasional adverse effects of disulfiram, hepatotoxicity and drowsiness, do not occur with calcium carbimide.[184]

- Ondansetron and topiramate are supported by tentative evidence in people with certain genetic patterns.[185][186] Evidence for ondansetron is stronger in people who have recently started to abuse alcohol.[185] Topiramate is a derivative of the naturally occurring sugar monosaccharide D-fructose. Review articles characterize topiramate as showing "encouraging",[185] "promising",[185] "efficacious",[187] and "insufficient"[188] results in the treatment of alcohol use disorders.[185][187][188]

Evidence does not support the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), antipsychotics, or gabapentin.[179]

Research

[edit]Topiramate, a derivative of the naturally occurring sugar monosaccharide D-fructose, has been found effective in helping alcoholics quit or cut back on the amount they drink. Evidence suggests that topiramate antagonizes excitatory glutamate receptors, inhibits dopamine release, and enhances inhibitory gamma-aminobutyric acid function. A 2008 review of the effectiveness of topiramate concluded that the results of published trials are promising, however as of 2008, data was insufficient to support using topiramate in conjunction with brief weekly compliance counseling as a first-line agent for alcohol dependence.[189] A 2010 review found that topiramate may be superior to existing alcohol pharmacotherapeutic options. Topiramate effectively reduces craving and alcohol withdrawal severity as well as improving quality-of-life-ratings.[190]

Baclofen, a GABAB receptor agonist, is under study for the treatment of alcoholism.[191] According to a 2017 Cochrane Systematic Review, there is insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness or safety for the use of baclofen for withdrawal symptoms in alcoholism.[192] Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy is under study for the treatment of patients with alcohol use disorder.[193][194]

Dual addictions and dependencies

[edit]Alcoholics may also require treatment for other psychotropic drug addictions and drug dependencies. The most common dual dependence syndrome with alcohol dependence is benzodiazepine dependence, with studies showing 10–20% of alcohol-dependent individuals had problems of dependence and/or misuse problems of benzodiazepine drugs such as diazepam or clonazepam. These drugs are, like alcohol, depressants. Benzodiazepines may be used legally, if they are prescribed by doctors for anxiety problems or other mood disorders, or they may be purchased as illegal drugs. Benzodiazepine use increases cravings for alcohol and the volume of alcohol consumed by problem drinkers.[195]

Benzodiazepine dependency requires careful reduction in dosage to avoid benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome and other health consequences. Dependence on other sedative-hypnotics such as zolpidem and zopiclone as well as opiates and illegal drugs is common in alcoholics. Alcohol itself is a sedative-hypnotic and is cross-tolerant with other sedative-hypnotics such as barbiturates, benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepines. Dependence upon and withdrawal from sedative-hypnotics can be medically severe and, as with alcohol withdrawal, there is a risk of psychosis or seizures if not properly managed.[196]

Epidemiology

[edit]

The World Health Organization estimates that as of 2016[update] there are about 380 million people with alcoholism worldwide (5.1% of the population over 15 years of age),[15][16] with it being most common among males and young adults.[4] Geographically, it is least common in Africa (1.1% of the population) and has the highest rates in Eastern Europe (11%).[4]

As of 2015[update] in the United States, about 17 million (7%) of adults and 0.7 million (2.8%) of those age 12 to 17 years of age are affected.[13] About 12% of American adults have had an alcohol dependence problem at some time in their life.[198]

In the United States and Western Europe, 10–20% of men and 5–10% of women at some point in their lives will meet criteria for alcoholism.[199] In England, the number of "dependent drinkers" was calculated as over 600,000 in 2019.[200] Estonia had the highest death rate from alcohol in Europe in 2015 at 8.8 per 100,000 population.[201] In the United States, 30% of people admitted to hospital have a problem related to alcohol.[202]

Within the medical and scientific communities, there is a broad consensus regarding alcoholism as a disease state. For example, the American Medical Association considers alcohol a drug and states that "drug addiction is a chronic, relapsing brain disease characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use despite often devastating consequences. It results from a complex interplay of biological vulnerability, environmental exposure, and developmental factors (e.g., stage of brain maturity)."[203] Alcoholism has a higher prevalence among men, though, in recent decades, the proportion of female alcoholics has increased.[53] Current evidence indicates that in both men and women, alcoholism is 50–60% genetically determined, leaving 40–50% for environmental influences.[204] Most alcoholics develop alcoholism during adolescence or young adulthood.[88]

Prognosis

[edit]

Alcoholism often reduces a person's life expectancy by around ten years.[23] The most common cause of death in alcoholics is from cardiovascular complications.[205] There is a high rate of suicide in chronic alcoholics, which increases the longer a person drinks. Approximately 3–15% of alcoholics die by suicide,[206] and research has found that over 50% of all suicides are associated with alcohol or drug dependence. This is believed to be due to alcohol causing physiological distortion of brain chemistry, as well as social isolation. Suicide is also common in adolescent alcohol abusers. Research in 2000 found that 25% of suicides in adolescents were related to alcohol abuse.[207]

Among those with alcohol dependence after one year, some met the criteria for low-risk drinking, even though only 26% of the group received any treatment, with the breakdown as follows: 25% were found to be still dependent, 27% were in partial remission (some symptoms persist), 12% asymptomatic drinkers (consumption increases chances of relapse) and 36% were fully recovered – made up of 18% low-risk drinkers plus 18% abstainers.[208] In contrast, however, the results of a long-term (60-year) follow-up of two groups of alcoholic men indicated that "return to controlled drinking rarely persisted for much more than a decade without relapse or evolution into abstinence ... return-to-controlled drinking, as reported in short-term studies, is often a mirage."[173]

History

[edit]

The term, Dipsomania was coined by German physician C. W. Hufeland in 1819 before it was superseded by alcoholism.[209][210] That term now has a more specific meaning.[211] The term alcoholism was first used by Swedish physician Magnus Huss in an 1852 publication to describe the systemic adverse effects of alcohol.[17]

Alcohol has a long history of use and misuse throughout recorded history. Biblical, Egyptian and Babylonian sources record the history of abuse and dependence on alcohol. In some ancient cultures alcohol was worshiped and in others, its misuse was condemned. Excessive alcohol misuse and drunkenness were recognized as causing social problems even thousands of years ago. However, the defining of habitual drunkenness as it was then known as and its adverse consequences were not well established medically until the 18th century. In 1647 a Greek monk named Agapios was the first to document that chronic alcohol misuse was associated with toxicity to the nervous system and body which resulted in a range of medical disorders such as seizures, paralysis, and internal bleeding. In the 1910s and 1920s, the effects of alcohol misuse and chronic drunkenness boosted membership of the temperance movement and led to the prohibition of alcohol in many countries in North America and the Nordic countries, nationwide bans on the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages that generally remained in place until the late 1920s or early 1930s; these policies resulted in the decline of death rates from cirrhosis and alcoholism.[212] In 2005, alcohol dependence and misuse was estimated to cost the US economy approximately 220 billion dollars per year, more than cancer and obesity.[213]

Evolution

[edit]Overview

[edit]Alcoholism is a very complex and difficult problem to understand and solve in society. The evolutionary perspective is often overlooked but is a key perspective in understanding this disease. The evolution of alcoholism is thought to originate at the consumption of fermented fruits.[214] Those that are able to find and successfully consume ripe fruit had an advantage because of the additional source of nutrients.[214] This led to an association of ethanol (found in fermenting fruits) with energy. Ethanol is produced inside of ripening fruits which contain significant amounts of nutrients and high caloric value. Natural selection favoring primates attracted to alcohol, even if the benefits were not direct, is one hypothesis for why some people are more susceptible to alcoholism than others.[215] This is an example of Darwinian medicine, and is part of the explanation for why some people may be more susceptible, the whole story about who is more susceptible to alcoholism also includes, genetics, environment, family background, and other stressors, all of which are important and tend to be studied more than the evolutionary aspect. Alcoholism is a disease of nutritional excess, similar to obesity.[215] Early human consumption of ethanol was a byproduct as well as a source of nutrients, but in an industrial society where there is an excess amount of alcohol, this consumption can become a problem.[216]

Fermented fruit consumption

[edit]Early humans regularly ingested ethanol which was made from yeast-based fermentation of naturally occurring fruit sugars.[217] The sugars found in fruit are an incentive for dispersers to consume and then eventually disperse seeds; the fruit pulp also serves as the base for ethanol production.[217] The development of ethanol in fruits occurs during the ripening process which leaves fruits more available for consumption by dispersers. Unripe fruits contain seeds that have not matured, and if those seeds were to be eaten and dispersed it would be maladaptive. Unripe fruits are also less available to microbes[214] to consume. The ripening of fruit can be seen as a race between dispersers and microbes. Ethanol inhibits the growth of microbes but it also typically makes fruit inedible to vertebrates as well. So, when an organism is able to consume alcohol, those fruits are available to them and not others. There is also an additional advantage to ethanol consumption which is the high caloric value of ethanol. The caloric value of ethanol is 7.1 kcal/g which is nearly twice that of carbohydrates which is 4.1 kcal/g.[214]

Ancestral ethanol consumption

[edit]Humans originate from a primarily frugivorous (fruit eater) lineage of primates. A large part of primate evolution occurred in warm equatorial climates where fruit fermentation occurred quickly and regularly. The ancestors of human and nonhuman primates were routinely exposed to low levels of ethanol through their fruit eating.[217] This led to corresponding adaptation and preference for ethanol that has been preserved in modern humans.[216]

Hormetic effect

[edit]The Hormetic effect or Hormesis is another aspect of the ancestral relationship humans have with alcohol. The Homertic effect is the idea that low concentrations to stressors, in this case ethanol, can be beneficial, but higher concentrations are stressful and cause harm. The evolutionary explanation for hormesis is based on the assumption that natural selection maximises relative fitness.[217] This is an explanation for why organisms developed the metabolic machinery to consume ethanol in order to maximise its benefits. The Homertic effect in relation to alcohol consumption has not been studied thoroughly in humans but has in the fruit fly genus, Drosophila. The longevity of Drosophila is enhanced at very low concentrations of ethanol but is decreased at higher concentrations. Additionally, the ability to produce an abundant amount of offspring increases in the low concentration presence of ethanol. Other organisms whose diet consists of fermenting fruit share these same characteristics and this may also include humans, seeing as they do have the ability and metabolic equipment to have hormetic advantages from ethanol at low concentrations.[217]

Humans frugivory

[edit]Humans have a far reaching frugivorous dietary heritage. Frugivorous adaptations among primates is thought to have started at least 40 million years ago, though likely earlier. Humans' closest relatives, the chimpanzees, have a predominantly frugivorous diet which supports the idea of their common ancestor's frugivorous dietary heritage. Additionally, gibbons and orangutans are almost exclusively frugivory, while gorillas which are partially frugivory.[217] Because of this shared evolutionary history, nonhuman primates have been used as models to understand alcoholism. Researchers have used macaques to test whether natural selection supports genes for traits that lead to excessive alcohol consumption because these same traits may enhance fitness in other contexts. Because of close lineages, this may be true as well for humans.[218]

Modern alcoholism

[edit]In prehistoric human ancestry, there were advantages to human consumption of ethanol in fermenting fruits. But as the world changed and living conditions turned to resemble current modern industrial society, human access to ethanol changed as well. Similar to sugars and fats, ethanol was only found in very low concentrations and because of its tie to fruit sugars, human consumption of it was necessary. So, just like people crave sugar and fat because prehistorically they are only minimally obtainable and necessary for bodily functions, ethanol can also be craved and be over consumed. In society sugar, fats and ethanol are readily available and in combination with our craving for it, both obesity and alcoholism can be considered diseases of nutritional excess.[215]

Society and culture

[edit]The various health problems associated with long-term alcohol consumption are generally perceived as detrimental to society; for example, money due to lost labor-hours, medical costs due to injuries due to drunkenness and organ damage from long-term use, and secondary treatment costs, such as the costs of rehabilitation facilities and detoxification centers. Alcohol use is a major contributing factor for head injuries, motor vehicle injuries (27%), interpersonal violence (18%), suicides (18%), and epilepsy (13%).[219] Beyond the financial costs that alcohol consumption imposes, there are also significant social costs to both the alcoholic and their family and friends.[73] For instance, alcohol consumption by a pregnant woman can lead to an incurable and damaging condition known as fetal alcohol syndrome, which often results in cognitive deficits, mental health problems, an inability to live independently and an increased risk of criminal behaviour, all of which can cause emotional stress for parents and caregivers.[220][221]

Estimates of the economic costs of alcohol misuse, collected by the World Health Organization, vary from 1–6% of a country's GDP.[222] One Australian estimate pegged alcohol's social costs at 24% of all drug misuse costs; a similar Canadian study concluded alcohol's share was 41%.[223] One study quantified the cost to the UK of all forms of alcohol misuse in 2001 as £18.5–20 billion.[200][224] All economic costs in the United States in 2006 have been estimated at $223.5 billion.[225]

The idea of hitting rock bottom refers to an experience of stress that can be attributed to alcohol misuse.[226] There is no single definition for this idea, and people may identify their own lowest points in terms of lost jobs, lost relationships, health problems, legal problems, or other consequences of alcohol misuse.[227] The concept is promoted by 12-step recovery groups and researchers using the transtheoretical model of motivation for behavior change.[227] The first use of this slang phrase in the formal medical literature appeared in a 1965 review in the British Medical Journal,[227] which said that some men refused treatment until they "hit rock bottom", but that treatment was generally more successful for "the alcohol addict who has friends and family to support him" than for impoverished and homeless addicts.[228]

Stereotypes of alcoholics are often found in fiction and popular culture. The "town drunk" is a stock character in Western popular culture. Stereotypes of drunkenness may be based on racism or xenophobia, as in the fictional depiction of the Irish as heavy drinkers.[229] Studies by social psychologists Stivers and Greeley attempt to document the perceived prevalence of high alcohol consumption amongst the Irish in America.[230] Alcohol consumption is relatively similar between many European cultures, the United States, and Australia. In Asian countries that have a high gross domestic product, there is heightened drinking compared to other Asian countries, but it is nowhere near as high as it is in other countries like the United States. It is also inversely seen, with countries that have very low gross domestic product showing high alcohol consumption.[231] In a study done on Korean immigrants in Canada, they reported alcohol was typically an integral part of their meal but is the only time solo drinking should occur. They also generally believe alcohol is necessary at any social event, as it helps conversations start.[232]

Peyote, a psychoactive agent, has even shown promise in treating alcoholism. Alcohol had actually replaced peyote as Native Americans' psychoactive agent of choice in rituals when peyote was outlawed.[233]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Twelve-Step Facilitation (TSF) interventions include extended counseling, adopting some of the techniques and principles of AA, as well as brief interventions designed to link individuals to community AA groups."[32]

- ^ non-inferiority has a specialized meaning in research design and statistical analysis; for more information see https://healthjournalism.org/glossary-terms/non-inferiority/; see also Schumi J, Wittes JT. Through the looking glass: understanding non-inferiority. Trials. 2011;12:106. Published 2011 May 3. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-12-106.

References

[edit]- ^ "Alcoholism MeSH Descriptor Data 2020". meshb.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Alcohol Use Disorder: A Comparison Between DSM–IV and DSM–5". November 2013. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Fetal Alcohol Exposure". 14 September 2011. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5 ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. pp. 490–97. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1.

- ^ a b c d "Alcohol's Effects on the Body". 14 September 2011. Archived from the original on 3 June 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ Borges G, Bagge CL, Cherpitel CJ, Conner KR, Orozco R, Rossow I (April 2017). "A meta-analysis of acute use of alcohol and the risk of suicide attempt". Psychological Medicine. 47 (5): 949–957. doi:10.1017/S0033291716002841. PMC 5340592. PMID 27928972.

- ^ a b c Moonat S, Pandey SC (2012). "Stress, epigenetics, and alcoholism". Alcohol Research. 34 (4): 495–505. doi:10.35946/arcr.v34.4.13. PMC 3860391. PMID 23584115.

- ^ a b c Morgan-Lopez AA, Fals-Stewart W (May 2006). "Analytic complexities associated with group therapy in substance abuse treatment research: problems, recommendations, and future directions". Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 14 (2): 265–73. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.265. PMC 4631029. PMID 16756430.

- ^ a b c d e Blondell RD (February 2005). "Ambulatory detoxification of patients with alcohol dependence". American Family Physician. 71 (3): 495–502. PMID 15712624.

- ^ a b Testino G, Leone S, Borro P (December 2014). "Treatment of alcohol dependence: recent progress and reduction of consumption". Minerva Medica. 105 (6): 447–66. PMID 25392958.

- ^ Kelly JF, Humphreys K, Ferri M (2020). "Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (3) CD012880. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012880.pub2. PMC 7065341. PMID 32159228.

- ^ Glantz MD, Bharat C, Degenhardt L, et al. (March 2020). "The epidemiology of alcohol use disorders cross-nationally: Findings from the World Mental Health Surveys". Addictive Behaviors. 102 106128. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106128. PMC 7416527. PMID 31865172.

- ^ a b c d "Alcohol Facts and Statistics". National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). 14 September 2011. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ Littrell J (2014). Understanding and Treating Alcoholism Volume I: An Empirically Based Clinician's Handbook for the Treatment of Alcoholism: Volume II: Biological, Psychological, and Social Aspects of Alcohol Consumption and Abuse. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-317-78314-5. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017.

The World Health Organization defines alcoholism as any drinking which results in problems

- ^ a b Global status report on alcohol and health 2018 (PDF). World Health Organization. 2018. pp. 72, 80. ISBN 978-92-4-156563-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 July 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ a b "World Population Prospects – Population Division". United Nations. Archived from the original on 15 June 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ a b Alcoholismus chronicus, eller Chronisk alkoholssjukdom. Stockholm und Leipzig. 1852. Retrieved 19 February 2008.

- ^ a b Morris J, Moss AC, Albery IP, Heather N (1 January 2022). "The 'alcoholic other': Harmful drinkers resist problem recognition to manage identity threat". Addictive Behaviors. 124 107093. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107093. PMID 34500234. Archived from the original on 30 March 2024. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ a b Ashford RD, Brown AM, Curtis B (1 August 2018). "Substance use, recovery, and linguistics: The impact of word choice on explicit and implicit bias". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 189: 131–138. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.05.005. PMC 6330014. PMID 29913324.

- ^ Rehm J (2011). "The risks associated with alcohol use and alcoholism". Alcohol Research & Health. 34 (2): 135–143. PMC 3307043. PMID 22330211.

- ^ Chambers English Thesaurus. Allied Publishers. p. 175. ISBN 978-81-86062-04-3.

- ^ Romeo J, Wärnberg J, Nova E, Díaz LE, Gómez-Martinez S, Marcos A (October 2007). "Moderate alcohol consumption and the immune system: a review". The British Journal of Nutrition. 98 (Suppl 1): S111-5. doi:10.1017/S0007114507838049. PMID 17922947.

- ^ a b c Schuckit MA (November 2014). "Recognition and management of withdrawal delirium (delirium tremens)". The New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (22): 2109–13. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1407298. PMID 25427113. S2CID 205116954. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ Ritzer G, ed. (15 February 2007). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosa039.pub2. ISBN 978-1-4051-2433-1. Archived from the original on 1 November 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ GBD 2013 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ Agarwal-Kozlowski K, Agarwal DP (April 2000). "[Genetic predisposition for alcoholism]". Therapeutische Umschau. 57 (4): 179–84. doi:10.1024/0040-5930.57.4.179. PMID 10804873.

- ^ Mersy DJ (April 2003). "Recognition of alcohol and substance abuse". American Family Physician. 67 (7): 1529–32. PMID 12722853.

- ^ "Health and Ethics Policies of the AMA House of Delegates" (PDF). June 2008. p. 33. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

H-30.997 Dual Disease Classification of Alcoholism: The AMA reaffirms its policy endorsing the dual classification of alcoholism under both the psychiatric and medical sections of the International Classification of Diseases. (Res. 22, I-79; Reaffirmed: CLRPD Rep. B, I-89; Reaffirmed: CLRPD Rep. B, I-90; Reaffirmed by CSA Rep. 14, A-97; Reaffirmed: CSAPH Rep. 3, A-07)

- ^ Higgins-Biddle JC, Babor TF (2018). "A review of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), AUDIT-C, and USAUDIT for screening in the United States: Past issues and future directions". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 44 (6): 578–586. doi:10.1080/00952990.2018.1456545. PMC 6217805. PMID 29723083.

- ^ DeVido JJ, Weiss RD (December 2012). "Treatment of the depressed alcoholic patient". Current Psychiatry Reports. 14 (6): 610–8. doi:10.1007/s11920-012-0314-7. PMC 3712746. PMID 22907336.

- ^ Albanese AP (November 2012). "Management of alcohol abuse". Clinics in Liver Disease. 16 (4): 737–62. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.006. PMID 23101980.

- ^ Kelly JF, Humphreys K, Ferri M (2020). "Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (CD012880): 15. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012880.pub2. PMC 7065341. PMID 32159228.

- ^ Kelly JF, Humphreys K, Ferri M (2020). "Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3) CD012880. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012880.pub2. PMC 7065341. PMID 32159228.

- ^ Kelly JF, Abry A, Ferri M, Humphreys K (2020). "Alcoholics Anonymous and 12-Step Facilitation Treatments for Alcohol Use Disorder: A Distillation of a 2020 Cochrane Review for Clinicians and Policy Makers". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 55 (6): 641–651. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agaa050. PMC 8060988. PMID 32628263.

- ^ "Alcoholics Anonymous most effective path to alcohol abstinence". 2020. Archived from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ "Binge Drinking". Center For Disease Control and Prevention. 28 February 2024. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ a b Hoffman PL, Tabakoff B (July 1996). "Alcohol dependence: a commentary on mechanisms". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 31 (4): 333–40. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a008159. PMID 8879279.

- ^ Dunn N, Cook CC (March 1999). "Psychiatric aspects of alcohol misuse". Hospital Medicine. 60 (3): 169–72. doi:10.12968/hosp.1999.60.3.1060. PMID 10476237.

- ^ Wilson R, Kolander CA (2003). Drug abuse prevention: a school and community partnership. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett. pp. 40–45. ISBN 978-0-7637-1461-1.

- ^ "Biology". The Volume Library. Vol. 1. Nashville, TN: The Southwestern Company. 2009. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-87197-208-8.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Dasgupta A (2017). "Alcohol a double-edged sword". Alcohol, Drugs, Genes and the Clinical Laboratory. Elsevier. p. 1–21. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-805455-0.00001-4. ISBN 978-0-12-805455-0. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ a b Holmwood C, Cock V (2023). "Physical Problems Associated with Alcohol". Alcohol Use: Assessment, Withdrawal Management, Treatment and Therapy. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 99–112. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-18381-2_6. ISBN 978-3-031-18380-5. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ Dasgupta A (2019). "Alcohol". Critical Issues in Alcohol and Drugs of Abuse Testing. Elsevier. p. 1–16. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-815607-0.00001-0. ISBN 978-0-12-815607-0. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ Greenfield TK, Cook WK, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Li L, Room R (2021). "Are Countries' Drink-Driving Policies Associated With Harms Involving Another Driver's Impairment?". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 45 (2): 429–435. doi:10.1111/acer.14526. ISSN 0145-6008. PMC 7887042. PMID 33277939.

- ^ "No level of alcohol consumption is safe for our health". www.who.int. World Health Organization. Retrieved 27 September 2025.

- ^ a b O'Keefe JH, Bhatti SK, Bajwa A, DiNicolantonio JJ, Lavie CJ (March 2014). "Alcohol and cardiovascular health: the dose makes the poison…or the remedy". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 89 (3): 382–93. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.11.005. PMID 24582196.

- ^ American Medical Association (2003). "Duodenal Ulcer". In Leiken JS, Lipsky MS (eds.). Complete Medical Encyclopedia (First ed.). New York: Random House Reference. p. 485. ISBN 978-0-8129-9100-0. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ Gormley M, Creaney G, Schache A, Ingarfield K, Conway DI (11 November 2022). "Reviewing the epidemiology of head and neck cancer: definitions, trends and risk factors". British Dental Journal. 233 (9): 780–786. doi:10.1038/s41415-022-5166-x. ISSN 0007-0610. PMC 9652141. PMID 36369568.

- ^ Müller D, Koch RD, von Specht H, Völker W, Münch EM (March 1985). "[Neurophysiologic findings in chronic alcohol abuse]". Psychiatrie, Neurologie, und Medizinische Psychologie (in German). 37 (3): 129–32. PMID 2988001.

- ^ Testino G (2008). "Alcoholic diseases in hepato-gastroenterology: a point of view". Hepato-Gastroenterology. 55 (82–83): 371–7. PMID 18613369.

- ^ 10th Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health Archived 13 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 2000, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

- ^ a b c Blum LN, Nielsen NH, Riggs JA (September 1998). "Alcoholism and alcohol abuse among women: report of the Council on Scientific Affairs. American Medical Association". Journal of Women's Health. 7 (7): 861–71. doi:10.1089/jwh.1998.7.861. PMID 9785312.

- ^ a b Walter H, Gutierrez K, Ramskogler K, Hertling I, Dvorak A, Lesch OM (November 2003). "Gender-specific differences in alcoholism: implications for treatment". Archives of Women's Mental Health. 6 (4): 253–8. doi:10.1007/s00737-003-0014-8. PMID 14628177. S2CID 6972064.

- ^ Mihai B, Lăcătuşu C, Graur M (April–June 2008). "[Alcoholic ketoacidosis]". Revista Medico-Chirurgicala a Societatii de Medici Si Naturalisti Din Iasi. 112 (2): 321–6. PMID 19294998.

- ^ Sibaï K, Eggimann P (September 2005). "[Alcoholic ketoacidosis: not rare cause of metabolic acidosis]". Revue Médicale Suisse. 1 (32): 2106, 2108–10, 2112–5. doi:10.53738/REVMED.2005.1.32.2106. PMID 16238232.

- ^ Cederbaum AI (November 2012). "Alcohol metabolism". Clinics in Liver Disease. 16 (4): 667–85. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002. PMC 3484320. PMID 23101976.

- ^ a b Bakalkin G (8 July 2008). "Alcoholism-associated molecular adaptations in brain neurocognitive circuits". Eurekalert.org. Archived from the original on 30 November 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ Oscar-Berman M, Marinkovic K (2003). "Alcoholism and the brain: an overview". Alcohol Research & Health. 27 (2): 125–33. PMC 6668884. PMID 15303622.

- ^ Uekermann J, Daum I (May 2008). "Social cognition in alcoholism: a link to prefrontal cortex dysfunction?". Addiction. 103 (5): 726–35. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02157.x. PMID 18412750.

- ^ Wetterling T, Junghanns K (December 2000). "Psychopathology of alcoholics during withdrawal and early abstinence". European Psychiatry. 15 (8): 483–8. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(00)00519-8. PMID 11175926. S2CID 24094651.

- ^ Schuckit MA (November 1983). "Alcoholism and other psychiatric disorders". Hospital & Community Psychiatry. 34 (11): 1022–7. doi:10.1176/ps.34.11.1022. PMID 6642446.

- ^ Cowley DS (January 1992). "Alcohol abuse, substance abuse, and panic disorder". The American Journal of Medicine. 92 (1A): 41S – 48S. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(92)90136-Y. PMID 1346485.

- ^ Cosci F, Schruers KR, Abrams K, Griez EJ (June 2007). "Alcohol use disorders and panic disorder: a review of the evidence of a direct relationship". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 68 (6): 874–80. doi:10.4088/JCP.v68n0608. PMID 17592911.

- ^ Grant BF, Harford TC (October 1995). "Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol use disorders and major depression: results of a national survey". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 39 (3): 197–206. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(95)01160-4. PMID 8556968. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ Kandel DB, Huang FY, Davies M (October 2001). "Comorbidity between patterns of substance use dependence and psychiatric syndromes". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 64 (2): 233–41. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(01)00126-0. PMID 11543993.

- ^ Cornelius JR, Bukstein O, Salloum I, Clark D (2003). "Alcohol and psychiatric comorbidity". Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Recent Dev Alcohol. Vol. 16. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. pp. 361–74. doi:10.1007/0-306-47939-7_24. ISBN 978-0-306-47258-9. ISSN 0738-422X. PMID 12638646.

- ^ Schuckit MA, Tipp JE, Bergman M, Reich W, Hesselbrock VM, Smith TL (July 1997). "Comparison of induced and independent major depressive disorders in 2,945 alcoholics". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 154 (7): 948–57. doi:10.1176/ajp.154.7.948. PMID 9210745.

- ^ Schuckit MA, Tipp JE, Bucholz KK, Nurnberger JI, Hesselbrock VM, Crowe RR, et al. (October 1997). "The life-time rates of three major mood disorders and four major anxiety disorders in alcoholics and controls". Addiction. 92 (10): 1289–304. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1997.tb02848.x. PMID 9489046. S2CID 14958283.

- ^ Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Danko GP, Pierson J, Trim R, Nurnberger JI, et al. (November 2007). "A comparison of factors associated with substance-induced versus independent depressions". Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 68 (6): 805–12. doi:10.15288/jsad.2007.68.805. PMID 17960298. S2CID 17528609.

- ^ Schuckit M (June 1983). "Alcoholic patients with secondary depression". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 140 (6): 711–4. doi:10.1176/ajp.140.6.711. PMID 6846629.

- ^ a b c Karrol BR (2002). "Women and alcohol use disorders: a review of important knowledge and its implications for social work practitioners". Journal of Social Work. 2 (3): 337–56. doi:10.1177/146801730200200305. S2CID 73186615.

- ^ Nolen-Hoeksema S (2004). "Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems". Clinical Psychology Review. 24 (8): 981–1010. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003. PMID 15533281. Retrieved 25 July 2025.

- ^ a b c McCully C (2004). Goodbye Mr. Wonderful. Alcohol, Addition and Early Recovery. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84310-265-6. Archived from the original on 21 November 2009.

- ^ Isralowitz R (2004). Drug use: a reference handbook. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 122–23. ISBN 978-1-57607-708-5. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ Langdana FK (2009). Macroeconomic Policy: Demystifying Monetary and Fiscal Policy (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-387-77665-1. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ Gifford M (2009). Alcoholism (Biographies of Disease). Greenwood Press. pp. 89–91. ISBN 978-0-313-35908-8.