Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

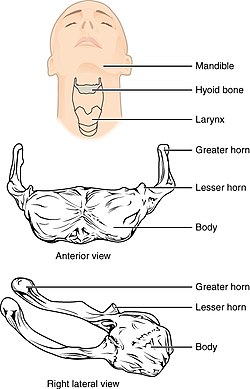

Hyoid bone

View on Wikipedia| Hyoid | |

|---|---|

The hyoid bone, present at the front of the neck, has a body and two sets of horns | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Second and third branchial arch[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | os hyoideum |

| MeSH | D006928 |

| TA98 | A02.1.16.001 |

| TA2 | 876 |

| FMA | 52749 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The hyoid bone (lingual bone or tongue-bone) (/ˈhaɪɔɪd/[2][3]) is a horseshoe-shaped bone situated in the anterior midline of the neck between the chin and the thyroid cartilage. At rest, it lies between the base of the mandible and the third cervical vertebra.

Unlike other bones, the hyoid is only distantly articulated to other bones by muscles or ligaments. It is the only bone in the human body that is not connected to any other bones. The hyoid is anchored by muscles from the anterior, posterior and inferior directions, and aids in tongue movement and swallowing. The hyoid bone provides attachment to the muscles of the floor of the mouth and the tongue above, the larynx below, and the epiglottis and pharynx behind.[citation needed]

Its name is derived from Greek hyoeides 'shaped like the letter upsilon (υ)'.[4][5]

Structure

[edit]

The hyoid bone is classed as an irregular bone and consists of a central part called the body, and two pairs of horns, the greater and lesser horns.

Body

[edit]The body of the hyoid bone is the central part of the hyoid bone.[clarification needed]

- At the front, the body is convex and directed forward and upward.

- It is crossed in its upper half by a well-marked transverse ridge with a slight downward convexity, and in many cases a vertical median ridge divides it into two lateral halves.

- The portion of the vertical ridge above the transverse line is present in a majority of specimens, but the lower portion is evident only in rare cases.[clarification needed]

- The anterior surface gives insertion to the geniohyoid muscle in the greater part of its extent both above and below the transverse ridge; a portion of the origin of the hyoglossus notches the lateral margin of the geniohyoid attachment.

- Below the transverse ridge the mylohyoid, sternohyoid, and omohyoid are inserted.

- At the back, the bone is smooth, concave, directed backward and downward, and separated from the epiglottis by the hyothyroid membrane and a quantity of loose areolar tissue; a bursa intervenes between it and the hyothyroid membrane.

- Above, the body is rounded, and gives attachment to the hyothyroid membrane and some aponeurotic fibers of the genioglossus.

- Below, the body affords insertion medially to the sternohyoid and laterally to the omohyoid and occasionally a portion of the thyrohyoid. It also gives attachment to the Levator glandulae thyreoideae, when this muscle is present.

Horns

[edit]

The greater and lesser horns (Latin: cornua) are two sections of bone that project from each side of the hyoid.

Greater horns

[edit]The greater horns project backward from the outer borders of the body; they are flattened from above downward and taper to their end, which is a bony tubercle connecting to the lateral thyrohyoid ligament. The upper surface of the greater horns are rough and close to its lateral border, and facilitates muscular attachment. The largest of muscles that attach to the upper surface of the greater horns are the hyoglossus and the middle pharyngeal constrictor, which extend along the whole length of the horns; the digastric muscle and stylohyoid muscle have small insertions in front of these near the junction of the body with the horns. To the medial border, the thyrohyoid membrane is attached, while the anterior half of the lateral border gives insertion to the thyrohyoid muscle.[citation needed]

Lesser horns

[edit]The lesser horns are two small, conical eminences, attached by their bases to the angles of junction between the body and greater horns of the hyoid bone. They are connected to the body of the bone by fibrous tissue, and occasionally to the greater horns by distinct diarthrodial joints, which usually persist throughout life, but occasionally become ankylosed. The lesser horns are situated in the line of the transverse ridge on the body and appear to be continuations of it. The apex of each horn gives attachment to the stylohyoid ligament; the chondroglossus rises from the medial side of the base.[citation needed]

Development

[edit]The second pharyngeal arch, also called the hyoid arch, gives rise to the lesser cornu of the hyoid and the upper part of the body of the hyoid. The cartilage of the third pharyngeal arch forms the greater cornu of the hyoid and the lower portion of the body of the hyoid.

The hyoid is ossified from six centers: two for the body, and one for each cornu. Ossification commences in the greater cornua toward the end of fetal development, in the hyoid body shortly afterward, and in the lesser cornua during the first or second year after birth. Until middle age, the connection between the body and greater cornu is fibrous.

In early life, the outer borders of the body are connected to the greater horns by synchondroses; after middle life, usually by bony union.

Blood supply

[edit]Blood is supplied to the hyoid bone via the lingual artery, which runs down from the tongue to the greater horns of the bone. The suprahyoid branch of the lingual artery runs along the upper border of the hyoid bone and supplies blood to the attached muscles.

Function

[edit]

The hyoid bone is present in many mammals. It allows a wider range of tongue, pharyngeal and laryngeal movements by bracing these structures alongside each other in order to produce variation.[6] Its descent in living creatures is not unique to Homo sapiens,[7] and does not allow the production of a wide range of sounds: with a lower larynx, men do not produce a wider range of sounds than women and two-year-old babies. Moreover, the larynx position of Neanderthals was not a handicap to producing speech sounds.[8] The discovery of a modern-looking hyoid bone of a Neanderthal man in the Kebara Cave in Israel led its discoverers to argue that the Neanderthals had a descended larynx, and thus human-like speech capabilities.[9] However, other researchers have claimed that the morphology of the hyoid is not indicative of the larynx's position. Recent research has indicated that the hyoid bone may have significant involvement in the ability to swallow. It has been hypothesized that the mammalian hyoid bone evolved in conjunction with the development of lactation, thus allowing babies to suckle milk.[10] It is necessary to take into consideration the skull base, the mandible and the cervical vertebrae and a cranial reference plane.[11][12]

Muscle attachments

[edit]A large number of muscles attach to the hyoid:[13]

- Superior

- Inferior

-

Muscles of the neck. Lateral view.

Clinical significance

[edit]The hyoid bone is important to a number of physiological functions, including breathing, swallowing and speech. It is also thought to play a key role in keeping the upper airway open during sleep,[14][15] and as such, the development and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA; characterized by repetitive collapse of the upper airway during sleep). A mechanistic involvement of the hyoid bone in OSA is supported by numerous studies demonstrating that a more inferiorly positioned hyoid bone is strongly associated with the presence and severity of the disorder.[16][17] Movement of the hyoid bone is also thought to be important in modifying upper airway properties, which was recently demonstrated in computer model simulations.[18] A surgical procedure that aims to potentially increase and improve the airway is called hyoid suspension.

Due to its position, the hyoid bone is not easily susceptible to fracture. In a suspected case of murder of an adult, a fractured hyoid strongly indicates strangulation. However, in children and adolescents, where the hyoid bone is still flexible as ossification is yet to be completed, strangulation is less likely to fracture the hyoid.

Other animals

[edit]The hyoid bone is derived from the lower half of the second gill arch in fish, which separates the first gill slit from the spiracle, and is often called the hyoid arch. In many vertebrates, it also incorporates elements of other gill arches, and has a correspondingly greater number of cornua. Amphibians and non-avian reptiles may have many cornua, while mammals (including humans) have two pairs, and birds only one. In birds, and some reptiles, the body of the hyoid is greatly extended forward, creating a solid bony support for the tongue.[19] The howler monkey Alouatta has a pneumatized hyoid bone, one of the few cases of postcranial pneumatization of bones outside Saurischia.

In woodpeckers, the hyoid bone is elongated, with the horns wrapping around the back of the skull. This is part of the system that keeps the brain cushioned and undamaged by the pecking action.

In mammals, the hyoid often determines whether one can roar. If the hyoid is incompletely ossified (for example: lions), it allows the animal to roar, but not purr. If the hyoid is completely ossified (for example: cheetahs), it does not allow the animal to roar, but instead will allow the animal to purr and meow, as seen in house cats (lions, cheetahs and house cats all belong to the family Felidae).[20]

-

The hyoid bone of a gecko with attached tracheal rings

-

Hyoid bones of various birds in the Natural History Museum, Vienna

In veterinary anatomy, the term hyoid apparatus is the collective term used to refer to the bones of the tongue—a pair of stylohyoidea, a pair of thyrohyoidea, and unpaired basihyoideum[21]—and associated, upper-gular connective tissues.[22] In humans, the single hyoid bone is an equivalent of the hyoid apparatus.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 177 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 177 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ hednk-023—Embryo Images at University of North Carolina

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary 2nd edition, 1989.

- ^ Entry "hyoid" Archived 2011-12-29 at the Wayback Machine in Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary Archived 2017-09-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Dorland illustrated medical dictionary

- ^ American heritage dictionary for English language

- ^ Nishimura, T. (2003). "Descent of the larynx in chimpanzee infants". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (12): 6930–6933. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.6930N. doi:10.1073/pnas.1231107100. PMC 165807. PMID 12775758. Descent of the larynx in chimpanzee infants

- ^ Nishimura, T.; et al. (2006). "Descent of the hyoid in chimpanzees: evolution of face flattening and speech". Journal of Human Evolution. 51 (3): 244–254. Bibcode:2006JHumE..51..244N. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.03.005. PMID 16730049.

- ^ Boë, L.J.; et al. (2002). "The potential of Neandertal vowel space was as large as that of modern humans". Journal of Phonetics. 30 (3): 465–484. doi:10.1006/jpho.2002.0170.

- ^ Arsenburg, B. et al., A reappraisal of the anatomical basis for speech in middle Paleolithic hominids, in: American Journal of Physiological Anthropology 83 (1990), pp. 137–146.

- ^ Fitch, Tecumseh W., The evolution of speech: a comparative review, in: Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 7, July 2000 ("Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-08-09. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)) - ^ Granat; et al. (2006). "Hyoid bone and larynx in Homo. Estimated position by biometrics". Biom. Hum. Et Anthropolol. 24 (3–4): 243–255.

- ^ Boë, L.J.; et al. (2006). "Variation and prediction of the hyoid bone position for modern Man and Neanderthal". Biom. Hum. Et Anthropolol. 24 (3–4): 257–271.

- ^ Shaw, S. M.; Martino, R. (2013). "The normal swallow: muscular and neurophysiological control". Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 46 (6): 937–956. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2013.09.006. PMID 24262952.

- ^ Amatoury, J; Kairaitis, K; Wheatley, JR; Bilston, LE; Amis, TC (1 April 2014). "Peripharyngeal tissue deformation and stress distributions in response to caudal tracheal displacement: pivotal influence of the hyoid bone?". Journal of Applied Physiology. 116 (7): 746–56. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01245.2013. PMID 24557799.

- ^ Amatoury, J; Kairaitis, K; Wheatley, JR; Bilston, LE; Amis, TC (1 February 2015). "Peripharyngeal tissue deformation, stress distributions, and hyoid bone movement in response to mandibular advancement". Journal of Applied Physiology. 118 (3): 282–91. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00668.2014. PMID 25505028.

- ^ Sforza, E; Bacon, W; Weiss, T; Thibault, A; Petiau, C; Krieger, J (February 2000). "Upper airway collapsibility and cephalometric variables in patients with obstructive sleep apnea". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 161 (2 Pt 1): 347–52. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9810091. PMID 10673170.

- ^ Genta, PR; Schorr, F; Eckert, DJ; Gebrim, E; Kayamori, F; Moriya, HT; Malhotra, A; Lorenzi-Filho, G (1 October 2014). "Upper airway collapsibility is associated with obesity and hyoid position". Sleep. 37 (10): 1673–8. doi:10.5665/sleep.4078. PMC 4173923. PMID 25197805.

- ^ Amatoury, J; Cheng, S; Kairaitis, K; Wheatley, JR; Amis, TC; Bilston, LE (2016). "Development and validation of a computational finite element model of the rabbit upper airway: simulations of mandibular advancement and tracheal displacement". J Appl Physiol. 120 (7): 743–57. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00820.2015. hdl:1959.4/unsworks_42699. PMID 26769952.

- ^ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. p. 214. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ^ SeaWorld https://seaworld.org/animals/all-about/cheetah/communication/

- ^ Shoshani J., Marchant G.H. (2001.) Hyoid apparatus: a little-known complex of bones and its "contribution" to proboscidean evolution, The World of Elephants - International Congress, Rome, pp. 668–675.

- ^ Klappenbach, Laura. "Hyoid Apparatus - Definition of Hyoid Apparatus". The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on 2012-01-20. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- ^ "hyoid apparatus - Definition". mondofacto.com. Archived from the original on 2011-11-08.

External links

[edit]- Lesson11 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (larynxskel1)