Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

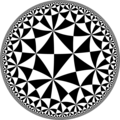

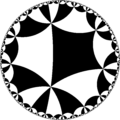

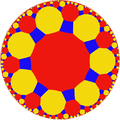

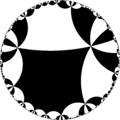

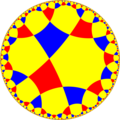

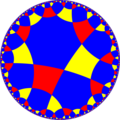

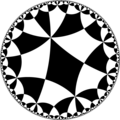

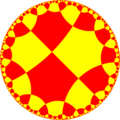

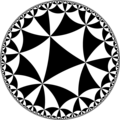

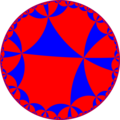

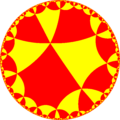

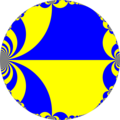

Uniform tilings in hyperbolic plane

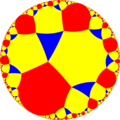

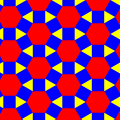

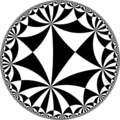

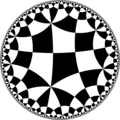

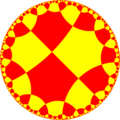

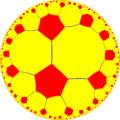

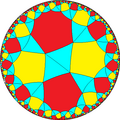

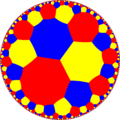

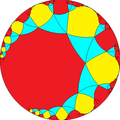

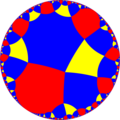

View on Wikipedia| Spherical | Euclidean | Hyperbolic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

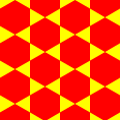

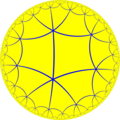

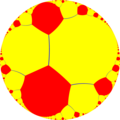

{5,3} 5.5.5 |

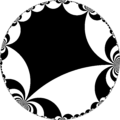

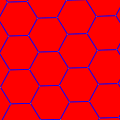

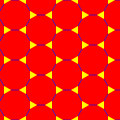

{6,3} 6.6.6 |

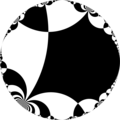

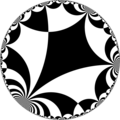

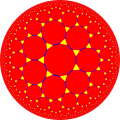

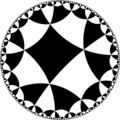

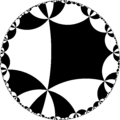

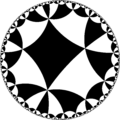

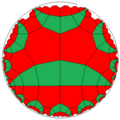

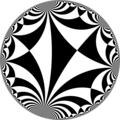

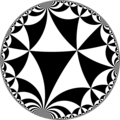

{7,3} 7.7.7 |

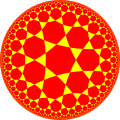

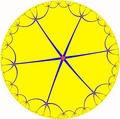

{∞,3} ∞.∞.∞ | ||

| Regular tilings {p,q} of the sphere, Euclidean plane, and hyperbolic plane using regular pentagonal, hexagonal and heptagonal and apeirogonal faces. | |||||

t{5,3} 10.10.3 |

t{6,3} 12.12.3 |

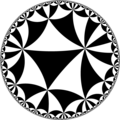

t{7,3} 14.14.3 |

t{∞,3} ∞.∞.3 | ||

| Truncated tilings have 2p.2p.q vertex figures from regular {p,q}. | |||||

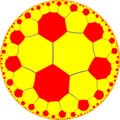

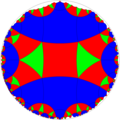

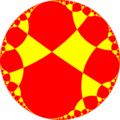

r{5,3} 3.5.3.5 |

r{6,3} 3.6.3.6 |

r{7,3} 3.7.3.7 |

r{∞,3} 3.∞.3.∞ | ||

| Quasiregular tilings are similar to regular tilings but alternate two types of regular polygon around each vertex. | |||||

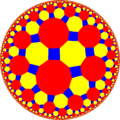

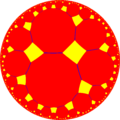

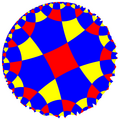

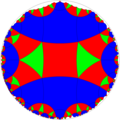

rr{5,3} 3.4.5.4 |

rr{6,3} 3.4.6.4 |

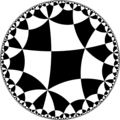

rr{7,3} 3.4.7.4 |

rr{∞,3} 3.4.∞.4 | ||

| Semiregular tilings have more than one type of regular polygon. | |||||

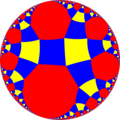

tr{5,3} 4.6.10 |

tr{6,3} 4.6.12 |

tr{7,3} 4.6.14 |

tr{∞,3} 4.6.∞ | ||

| Omnitruncated tilings have three or more even-sided regular polygons. | |||||

| Symmetry | Triangular dihedral symmetry

|

Tetrahedral

|

Octahedral

|

Icosahedral

|

p6m symmetry

|

[3,7] symmetry

|

[3,8] symmetry

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starting solid Operation |

Symbol {p,q} |

Triangular hosohedron {2,3}  |

Triangular dihedron {3,2}  |

Tetrahedron {3,3}  |

Cube {4,3} |

Octahedron {3,4}  |

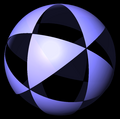

Dodecahedron {5,3}  |

Icosahedron {3,5}  |

Hexagonal tiling {6,3}  |

Triangular tiling {3,6}  |

Heptagonal tiling {7,3}  |

Order-7 triangular tiling {3,7}  |

Octagonal tiling {8,3}  |

Order-8 triangular tiling {3,8}

|

| Truncation (t) | t{p,q} |

triangular prism |

truncated triangular dihedron (Half of the "edges" count as degenerate digon faces. The other half are normal edges.) (Half of the "edges" count as degenerate digon faces. The other half are normal edges.) |

truncated tetrahedron |

truncated cube |

truncated octahedron |

truncated dodecahedron |

truncated icosahedron |

Truncated hexagonal tiling |

Truncated triangular tiling |

Truncated heptagonal tiling |

Truncated order-7 triangular tiling |

Truncated octagonal tiling |

Truncated order-8 triangular tiling

|

| Rectification (r) Ambo (a) |

r{p,q} |

tridihedron (All of the "edges" count as degenerate digon faces.) (All of the "edges" count as degenerate digon faces.) |

tetratetrahedron |

cuboctahedron |

icosidodecahedron |

Trihexagonal tiling |

Triheptagonal tiling |

Trioctagonal tiling

| ||||||

| Bitruncation (2t) Dual kis (dk) |

2t{p,q} |

truncated triangular dihedron (Half of the "edges" count as degenerate digon faces. The other half are normal edges.) (Half of the "edges" count as degenerate digon faces. The other half are normal edges.) |

triangular prism |

truncated tetrahedron |

truncated octahedron |

truncated cube |

truncated icosahedron |

truncated dodecahedron |

truncated triangular tiling |

truncated hexagonal tiling |

Truncated order-7 triangular tiling |

Truncated heptagonal tiling |

Truncated order-8 triangular tiling |

Truncated octagonal tiling

|

| Birectification (2r) Dual (d) |

2r{p,q} |

triangular dihedron {3,2}  |

triangular hosohedron {2,3}  |

tetrahedron |

octahedron |

cube |

icosahedron |

dodecahedron |

triangular tiling |

hexagonal tiling |

Order-7 triangular tiling |

Heptagonal tiling |

Order-8 triangular tiling |

Octagonal tiling

|

| Cantellation (rr) Expansion (e) |

rr{p,q} |

triangular prism (The "edge" between each pair of tetragons counts as a degenerate digon face. The other edges (the ones between a trigon and a tetragon) are normal edges.) (The "edge" between each pair of tetragons counts as a degenerate digon face. The other edges (the ones between a trigon and a tetragon) are normal edges.) |

rhombitetratetrahedron |

rhombicuboctahedron |

rhombicosidodecahedron  |

rhombitrihexagonal tiling |

Rhombitriheptagonal tiling  |

Rhombitrioctagonal tiling

| ||||||

| Snub rectified (sr) Snub (s) |

sr{p,q} |

triangular antiprism (Three yellow-yellow "edges", no two of which share any vertices, count as degenerate digon faces. The other edges are normal edges.) (Three yellow-yellow "edges", no two of which share any vertices, count as degenerate digon faces. The other edges are normal edges.) |

snub tetratetrahedron |

snub cuboctahedron |

snub icosidodecahedron |

snub trihexagonal tiling |

Snub triheptagonal tiling |

Snub trioctagonal tiling

| ||||||

| Cantitruncation (tr) Bevel (b) |

tr{p,q} |

hexagonal prism |

truncated tetratetrahedron |

truncated cuboctahedron |

truncated icosidodecahedron |

truncated trihexagonal tiling |

Truncated triheptagonal tiling |

Truncated trioctagonal tiling

| ||||||

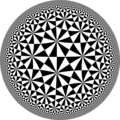

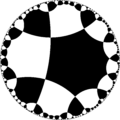

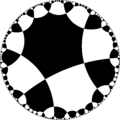

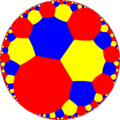

In hyperbolic geometry, a uniform hyperbolic tiling (or regular, quasiregular or semiregular hyperbolic tiling) is an edge-to-edge filling of the hyperbolic plane which has regular polygons as faces and is vertex-transitive (transitive on its vertices, isogonal, i.e. there is an isometry mapping any vertex onto any other). It follows that all vertices are congruent, and the tiling has a high degree of rotational and translational symmetry.

Uniform tilings can be identified by their vertex configuration, a sequence of numbers representing the number of sides of the polygons around each vertex. For example, 7.7.7 represents the heptagonal tiling which has 3 heptagons around each vertex. It is also regular since all the polygons are the same size, so it can also be given the Schläfli symbol {7,3}.

Uniform tilings may be regular (if also face- and edge-transitive), quasi-regular (if edge-transitive but not face-transitive) or semi-regular (if neither edge- nor face-transitive). For right triangles (p q 2), there are two regular tilings, represented by Schläfli symbol {p,q} and {q,p}.

Wythoff construction

[edit]

There are an infinite number of uniform tilings based on the Schwarz triangles (p q r) where 1/p + 1/q + 1/r < 1, where p, q, r are each orders of reflection symmetry at three points of the fundamental domain triangle – the symmetry group is a hyperbolic triangle group.

Each symmetry family contains 7 uniform tilings, defined by a Wythoff symbol or Coxeter-Dynkin diagram, 7 representing combinations of 3 active mirrors. An 8th represents an alternation operation, deleting alternate vertices from the highest form with all mirrors active.

Families with r = 2 contain regular hyperbolic tilings, defined by a Coxeter group such as [7,3], [8,3], [9,3], ... [5,4], [6,4], ....

Hyperbolic families with r = 3 or higher are given by (p q r) and include (4 3 3), (5 3 3), (6 3 3) ... (4 4 3), (5 4 3), ... (4 4 4)....

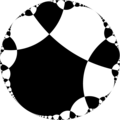

Hyperbolic triangles (p q r) define compact uniform hyperbolic tilings. In the limit any of p, q or r can be replaced by ∞ which defines a paracompact hyperbolic triangle and creates uniform tilings with either infinite faces (called apeirogons) that converge to a single ideal point, or infinite vertex figure with infinitely many edges diverging from the same ideal point.

More symmetry families can be constructed from fundamental domains that are not triangles.

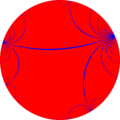

Selected families of uniform tilings are shown below (using the Poincaré disk model for the hyperbolic plane). Three of them – (7 3 2), (5 4 2), and (4 3 3) – and no others, are minimal in the sense that if any of their defining numbers is replaced by a smaller integer the resulting pattern is either Euclidean or spherical rather than hyperbolic; conversely, any of the numbers can be increased (even to infinity) to generate other hyperbolic patterns.

Each uniform tiling generates a dual uniform tiling, with many of them also given below.

Right triangle domains

[edit]There are infinitely many (p q 2) triangle group families. This article shows the regular tiling up to p, q = 8, and uniform tilings in 12 families: (7 3 2), (8 3 2), (5 4 2), (6 4 2), (7 4 2), (8 4 2), (5 5 2), (6 5 2) (6 6 2), (7 7 2), (8 6 2), and (8 8 2).

Regular hyperbolic tilings

[edit]The simplest set of hyperbolic tilings are regular tilings {p,q}, which exist in a matrix with the regular polyhedra and Euclidean tilings. The regular tiling {p,q} has a dual tiling {q,p} across the diagonal axis of the table. Self-dual tilings {2,2}, {3,3}, {4,4}, {5,5}, etc. pass down the diagonal of the table.

| Regular hyperbolic tiling table | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spherical (improper/Platonic)/Euclidean/hyperbolic (Poincaré disk: compact/paracompact/noncompact) tessellations with their Schläfli symbol | |||||||||||

| p \ q | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ... | ∞ | ... | iπ/λ |

| 2 |  {2,2} |

{2,3} |

{2,4} |

{2,5} |

{2,6} |

{2,7} |

{2,8} |

{2,∞} |

{2,iπ/λ} | ||

| 3 |  {3,2} |

(tetrahedron) {3,3} |

(octahedron) {3,4} |

(icosahedron) {3,5} |

(deltille) {3,6} |

{3,7} |

{3,8} |

{3,∞} |

{3,iπ/λ} | ||

| 4 |  {4,2} |

(cube) {4,3} |

(quadrille) {4,4} |

{4,5} |

{4,6} |

{4,7} |

{4,8} |

{4,∞} |

{4,iπ/λ} | ||

| 5 |  {5,2} |

(dodecahedron) {5,3} |

{5,4} |

{5,5} |

{5,6} |

{5,7} |

{5,8} |

{5,∞} |

{5,iπ/λ} | ||

| 6 |  {6,2} |

(hextille) {6,3} |

{6,4} |

{6,5} |

{6,6} |

{6,7} |

{6,8} |

{6,∞} |

{6,iπ/λ} | ||

| 7 | {7,2} |

{7,3} |

{7,4} |

{7,5} |

{7,6} |

{7,7} |

{7,8} |

{7,∞} |

{7,iπ/λ} | ||

| 8 | {8,2} |

{8,3} |

{8,4} |

{8,5} |

{8,6} |

{8,7} |

{8,8} |

{8,∞} |

{8,iπ/λ} | ||

| ... | |||||||||||

| ∞ |  {∞,2} |

{∞,3} |

{∞,4} |

{∞,5} |

{∞,6} |

{∞,7} |

{∞,8} |

{∞,∞} |

{∞,iπ/λ} | ||

| ... | |||||||||||

| iπ/λ |  {iπ/λ,2} |

{iπ/λ,3} |

{iπ/λ,4} |

{iπ/λ,5} |

{iπ/λ,6} |

{iπ/λ,7} |

{iπ/λ,8} |

{iπ/λ,∞} |

{iπ/λ, iπ/λ} | ||

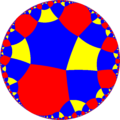

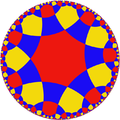

(7 3 2)

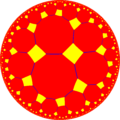

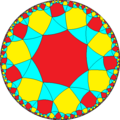

[edit]The (7 3 2) triangle group, Coxeter group [7,3], orbifold (*732) contains these uniform tilings:

| Uniform heptagonal/triangular tilings | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [7,3], (*732) | [7,3]+, (732) | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| {7,3} | t{7,3} | r{7,3} | t{3,7} | {3,7} | rr{7,3} | tr{7,3} | sr{7,3} | ||||

| Uniform duals | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| V73 | V3.14.14 | V3.7.3.7 | V6.6.7 | V37 | V3.4.7.4 | V4.6.14 | V3.3.3.3.7 | ||||

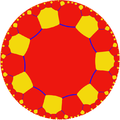

(8 3 2)

[edit]The (8 3 2) triangle group, Coxeter group [8,3], orbifold (*832) contains these uniform tilings:

| Uniform octagonal/triangular tilings | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [8,3], (*832) | [8,3]+ (832) |

[1+,8,3] (*443) |

[8,3+] (3*4) | ||||||||||

| {8,3} | t{8,3} | r{8,3} | t{3,8} | {3,8} | rr{8,3} s2{3,8} |

tr{8,3} | sr{8,3} | h{8,3} | h2{8,3} | s{3,8} | |||

| Uniform duals | |||||||||||||

| V83 | V3.16.16 | V3.8.3.8 | V6.6.8 | V38 | V3.4.8.4 | V4.6.16 | V34.8 | V(3.4)3 | V8.6.6 | V35.4 | |||

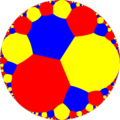

(5 4 2)

[edit]The (5 4 2) triangle group, Coxeter group [5,4], orbifold (*542) contains these uniform tilings:

| Uniform pentagonal/square tilings | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [5,4], (*542) | [5,4]+, (542) | [5+,4], (5*2) | [5,4,1+], (*552) | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

| {5,4} | t{5,4} | r{5,4} | 2t{5,4}=t{4,5} | 2r{5,4}={4,5} | rr{5,4} | tr{5,4} | sr{5,4} | s{5,4} | h{4,5} | ||

| Uniform duals | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

| V54 | V4.10.10 | V4.5.4.5 | V5.8.8 | V45 | V4.4.5.4 | V4.8.10 | V3.3.4.3.5 | V3.3.5.3.5 | V55 | ||

(6 4 2)

[edit]The (6 4 2) triangle group, Coxeter group [6,4], orbifold (*642) contains these uniform tilings. Because all the elements are even, each uniform dual tiling one represents the fundamental domain of a reflective symmetry: *3333, *662, *3232, *443, *222222, *3222, and *642 respectively. As well, all 7 uniform tiling can be alternated, and those have duals as well.

| Uniform tetrahexagonal tilings | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [6,4], (*642) (with [6,6] (*662), [(4,3,3)] (*443) , [∞,3,∞] (*3222) index 2 subsymmetries) (And [(∞,3,∞,3)] (*3232) index 4 subsymmetry) | |||||||||||

= = = |

= |

= = = |

= |

= = = |

= |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||

| {6,4} | t{6,4} | r{6,4} | t{4,6} | {4,6} | rr{6,4} | tr{6,4} | |||||

| Uniform duals | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||

| V64 | V4.12.12 | V(4.6)2 | V6.8.8 | V46 | V4.4.4.6 | V4.8.12 | |||||

| Alternations | |||||||||||

| [1+,6,4] (*443) |

[6+,4] (6*2) |

[6,1+,4] (*3222) |

[6,4+] (4*3) |

[6,4,1+] (*662) |

[(6,4,2+)] (2*32) |

[6,4]+ (642) | |||||

= |

= |

= |

= |

= |

= |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||

| h{6,4} | s{6,4} | hr{6,4} | s{4,6} | h{4,6} | hrr{6,4} | sr{6,4} | |||||

(7 4 2)

[edit]The (7 4 2) triangle group, Coxeter group [7,4], orbifold (*742) contains these uniform tilings:

| Uniform heptagonal/square tilings | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [7,4], (*742) | [7,4]+, (742) | [7+,4], (7*2) | [7,4,1+], (*772) | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

| {7,4} | t{7,4} | r{7,4} | 2t{7,4}=t{4,7} | 2r{7,4}={4,7} | rr{7,4} | tr{7,4} | sr{7,4} | s{7,4} | h{4,7} | ||

| Uniform duals | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| V74 | V4.14.14 | V4.7.4.7 | V7.8.8 | V47 | V4.4.7.4 | V4.8.14 | V3.3.4.3.7 | V3.3.7.3.7 | V77 | ||

(8 4 2)

[edit]The (8 4 2) triangle group, Coxeter group [8,4], orbifold (*842) contains these uniform tilings. Because all the elements are even, each uniform dual tiling one represents the fundamental domain of a reflective symmetry: *4444, *882, *4242, *444, *22222222, *4222, and *842 respectively. As well, all 7 uniform tiling can be alternated, and those have duals as well.

| Uniform octagonal/square tilings | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [8,4], (*842) (with [8,8] (*882), [(4,4,4)] (*444) , [∞,4,∞] (*4222) index 2 subsymmetries) (And [(∞,4,∞,4)] (*4242) index 4 subsymmetry) | |||||||||||

= = = |

= |

= = = |

= |

= = |

= |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||

| {8,4} | t{8,4} |

r{8,4} | 2t{8,4}=t{4,8} | 2r{8,4}={4,8} | rr{8,4} | tr{8,4} | |||||

| Uniform duals | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||

| V84 | V4.16.16 | V(4.8)2 | V8.8.8 | V48 | V4.4.4.8 | V4.8.16 | |||||

| Alternations | |||||||||||

| [1+,8,4] (*444) |

[8+,4] (8*2) |

[8,1+,4] (*4222) |

[8,4+] (4*4) |

[8,4,1+] (*882) |

[(8,4,2+)] (2*42) |

[8,4]+ (842) | |||||

= |

= |

= |

= |

= |

= |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||

| h{8,4} | s{8,4} | hr{8,4} | s{4,8} | h{4,8} | hrr{8,4} | sr{8,4} | |||||

| Alternation duals | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| V(4.4)4 | V3.(3.8)2 | V(4.4.4)2 | V(3.4)3 | V88 | V4.44 | V3.3.4.3.8 | |||||

(5 5 2)

[edit]The (5 5 2) triangle group, Coxeter group [5,5], orbifold (*552) contains these uniform tilings:

| Uniform pentapentagonal tilings | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [5,5], (*552) | [5,5]+, (552) | ||||||||||

= |

= |

= |

= |

= |

= |

= |

= | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| Order-5 pentagonal tiling {5,5} |

Truncated order-5 pentagonal tiling t{5,5} |

Order-4 pentagonal tiling r{5,5} |

Truncated order-5 pentagonal tiling 2t{5,5} = t{5,5} |

Order-5 pentagonal tiling 2r{5,5} = {5,5} |

Tetrapentagonal tiling rr{5,5} |

Truncated order-4 pentagonal tiling tr{5,5} |

Snub pentapentagonal tiling sr{5,5} | ||||

| Uniform duals | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Order-5 pentagonal tiling V5.5.5.5.5 |

V5.10.10 | Order-5 square tiling V5.5.5.5 |

V5.10.10 | Order-5 pentagonal tiling V5.5.5.5.5 |

V4.5.4.5 | V4.10.10 | V3.3.5.3.5 | ||||

(6 5 2)

[edit]The (6 5 2) triangle group, Coxeter group [6,5], orbifold (*652) contains these uniform tilings:

| Uniform hexagonal/pentagonal tilings | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [6,5], (*652) | [6,5]+, (652) | [6,5+], (5*3) | [1+,6,5], (*553) | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

| {6,5} | t{6,5} | r{6,5} | 2t{6,5}=t{5,6} | 2r{6,5}={5,6} | rr{6,5} | tr{6,5} | sr{6,5} | s{5,6} | h{6,5} | ||

| Uniform duals | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| V65 | V5.12.12 | V5.6.5.6 | V6.10.10 | V56 | V4.5.4.6 | V4.10.12 | V3.3.5.3.6 | V3.3.3.5.3.5 | V(3.5)5 | ||

(6 6 2)

[edit]The (6 6 2) triangle group, Coxeter group [6,6], orbifold (*662) contains these uniform tilings:

| Uniform hexahexagonal tilings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [6,6], (*662) | ||||||

= |

= |

= |

= |

= |

= |

= |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| {6,6} = h{4,6} |

t{6,6} = h2{4,6} |

r{6,6} {6,4} |

t{6,6} = h2{4,6} |

{6,6} = h{4,6} |

rr{6,6} r{6,4} |

tr{6,6} t{6,4} |

| Uniform duals | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| V66 | V6.12.12 | V6.6.6.6 | V6.12.12 | V66 | V4.6.4.6 | V4.12.12 |

| Alternations | ||||||

| [1+,6,6] (*663) |

[6+,6] (6*3) |

[6,1+,6] (*3232) |

[6,6+] (6*3) |

[6,6,1+] (*663) |

[(6,6,2+)] (2*33) |

[6,6]+ (662) |

|

|

|

|

| ||

| h{6,6} | s{6,6} | hr{6,6} | s{6,6} | h{6,6} | hrr{6,6} | sr{6,6} |

(8 6 2)

[edit]The (8 6 2) triangle group, Coxeter group [8,6], orbifold (*862) contains these uniform tilings.

| Uniform octagonal/hexagonal tilings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [8,6], (*862) | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| {8,6} | t{8,6} |

r{8,6} | 2t{8,6}=t{6,8} | 2r{8,6}={6,8} | rr{8,6} | tr{8,6} |

| Uniform duals | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| V86 | V6.16.16 | V(6.8)2 | V8.12.12 | V68 | V4.6.4.8 | V4.12.16 |

| Alternations | ||||||

| [1+,8,6] (*466) |

[8+,6] (8*3) |

[8,1+,6] (*4232) |

[8,6+] (6*4) |

[8,6,1+] (*883) |

[(8,6,2+)] (2*43) |

[8,6]+ (862) |

|

|

| ||||

| h{8,6} | s{8,6} | hr{8,6} | s{6,8} | h{6,8} | hrr{8,6} | sr{8,6} |

| Alternation duals | ||||||

|

||||||

| V(4.6)6 | V3.3.8.3.8.3 | V(3.4.4.4)2 | V3.4.3.4.3.6 | V(3.8)8 | V3.45 | V3.3.6.3.8 |

(7 7 2)

[edit]The (7 7 2) triangle group, Coxeter group [7,7], orbifold (*772) contains these uniform tilings:

| Uniform heptaheptagonal tilings | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [7,7], (*772) | [7,7]+, (772) | ||||||||||

= |

= |

= |

= |

= |

= |

= |

= | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| {7,7} | t{7,7} |

r{7,7} | 2t{7,7}=t{7,7} | 2r{7,7}={7,7} | rr{7,7} | tr{7,7} | sr{7,7} | ||||

| Uniform duals | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| V77 | V7.14.14 | V7.7.7.7 | V7.14.14 | V77 | V4.7.4.7 | V4.14.14 | V3.3.7.3.7 | ||||

(8 8 2)

[edit]The (8 8 2) triangle group, Coxeter group [8,8], orbifold (*882) contains these uniform tilings:

| Uniform octaoctagonal tilings | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [8,8], (*882) | |||||||||||

= |

= |

= |

= |

= |

= |

= | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||

| {8,8} | t{8,8} |

r{8,8} | 2t{8,8}=t{8,8} | 2r{8,8}={8,8} | rr{8,8} | tr{8,8} | |||||

| Uniform duals | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||

| V88 | V8.16.16 | V8.8.8.8 | V8.16.16 | V88 | V4.8.4.8 | V4.16.16 | |||||

| Alternations | |||||||||||

| [1+,8,8] (*884) |

[8+,8] (8*4) |

[8,1+,8] (*4242) |

[8,8+] (8*4) |

[8,8,1+] (*884) |

[(8,8,2+)] (2*44) |

[8,8]+ (882) | |||||

= |

= | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

| |||||||

| h{8,8} | s{8,8} | hr{8,8} | s{8,8} | h{8,8} | hrr{8,8} | sr{8,8} | |||||

| Alternation duals | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| V(4.8)8 | V3.4.3.8.3.8 | V(4.4)4 | V3.4.3.8.3.8 | V(4.8)8 | V46 | V3.3.8.3.8 | |||||

General triangle domains

[edit]There are infinitely many general triangle group families (p q r). This article shows uniform tilings in 9 families: (4 3 3), (4 4 3), (4 4 4), (5 3 3), (5 4 3), (5 4 4), (6 3 3), (6 4 3), and (6 4 4).

(4 3 3)

[edit]The (4 3 3) triangle group, Coxeter group [(4,3,3)], orbifold (*433) contains these uniform tilings. Without right angles in the fundamental triangle, the Wythoff constructions are slightly different. For instance in the (4,3,3) triangle family, the snub form has six polygons around a vertex and its dual has hexagons rather than pentagons. In general the vertex figure of a snub tiling in a triangle (p,q,r) is p. 3.q.3.r.3, being 4.3.3.3.3.3 in this case below.

| Symmetry: [(4,3,3)], (*433) | [(4,3,3)]+, (433) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

| h{8,3} t0(4,3,3) |

r{3,8}1/2 t0,1(4,3,3) |

h{8,3} t1(4,3,3) |

h2{8,3} t1,2(4,3,3) |

{3,8}1/2 t2(4,3,3) |

h2{8,3} t0,2(4,3,3) |

t{3,8}1/2 t0,1,2(4,3,3) |

s{3,8}1/2 s(4,3,3) | |||

| Uniform duals | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

| V(3.4)3 | V3.8.3.8 | V(3.4)3 | V3.6.4.6 | V(3.3)4 | V3.6.4.6 | V6.6.8 | V3.3.3.3.3.4 | |||

(4 4 3)

[edit]The (4 4 3) triangle group, Coxeter group [(4,4,3)], orbifold (*443) contains these uniform tilings.

| Uniform (4,4,3) tilings | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [(4,4,3)] (*443) | [(4,4,3)]+ (443) |

[(4,4,3+)] (3*22) |

[(4,1+,4,3)] (*3232) | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| h{6,4} t0(4,4,3) |

h2{6,4} t0,1(4,4,3) |

{4,6}1/2 t1(4,4,3) |

h2{6,4} t1,2(4,4,3) |

h{6,4} t2(4,4,3) |

r{6,4}1/2 t0,2(4,4,3) |

t{4,6}1/2 t0,1,2(4,4,3) |

s{4,6}1/2 s(4,4,3) |

hr{4,6}1/2 hr(4,3,4) |

h{4,6}1/2 h(4,3,4) |

q{4,6} h1(4,3,4) |

| Uniform duals | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| V(3.4)4 | V3.8.4.8 | V(4.4)3 | V3.8.4.8 | V(3.4)4 | V4.6.4.6 | V6.8.8 | V3.3.3.4.3.4 | V(4.4.3)2 | V66 | V4.3.4.6.6 |

(4 4 4)

[edit]The (4 4 4) triangle group, Coxeter group [(4,4,4)], orbifold (*444) contains these uniform tilings.

| Uniform (4,4,4) tilings | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [(4,4,4)], (*444) | [(4,4,4)]+ (444) |

[(1+,4,4,4)] (*4242) |

[(4+,4,4)] (4*22) | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

| t0(4,4,4) h{8,4} |

t0,1(4,4,4) h2{8,4} |

t1(4,4,4) {4,8}1/2 |

t1,2(4,4,4) h2{8,4} |

t2(4,4,4) h{8,4} |

t0,2(4,4,4) r{4,8}1/2 |

t0,1,2(4,4,4) t{4,8}1/2 |

s(4,4,4) s{4,8}1/2 |

h(4,4,4) h{4,8}1/2 |

hr(4,4,4) hr{4,8}1/2 | ||

| Uniform duals | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

| V(4.4)4 | V4.8.4.8 | V(4.4)4 | V4.8.4.8 | V(4.4)4 | V4.8.4.8 | V8.8.8 | V3.4.3.4.3.4 | V88 | V(4,4)3 | ||

(5 3 3)

[edit]The (5 3 3) triangle group, Coxeter group [(5,3,3)], orbifold (*533) contains these uniform tilings.

| Uniform (5,3,3) tilings | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [(5,3,3)], (*533) | [(5,3,3)]+, (533) | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| h{10,3} t0(5,3,3) |

r{3,10}1/2 t0,1(5,3,3) |

h{10,3} t1(5,3,3) |

h2{10,3} t1,2(5,3,3) |

{3,10}1/2 t2(5,3,3) |

h2{10,3} t0,2(5,3,3) |

t{3,10}1/2 t0,1,2(5,3,3) |

s{3,10}1/2 ht0,1,2(5,3,3) | ||||

| Uniform duals | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| V(3.5)3 | V3.10.3.10 | V(3.5)3 | V3.6.5.6 | V(3.3)5 | V3.6.5.6 | V6.6.10 | V3.3.3.3.3.5 | ||||

(5 4 3)

[edit]The (5 4 3) triangle group, Coxeter group [(5,4,3)], orbifold (*543) contains these uniform tilings.

| (5,4,3) uniform tilings | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [(5,4,3)], (*543) | [(5,4,3)]+, (543) | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| t0(5,4,3) (5,4,3) |

t0,1(5,4,3) r(3,5,4) |

t1(5,4,3) (4,3,5) |

t1,2(5,4,3) r(5,4,3) |

t2(5,4,3) (3,5,4) |

t0,2(5,4,3) r(4,3,5) |

t0,1,2(5,4,3) t(5,4,3) |

s(5,4,3) | ||||

| Uniform duals | |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| V(3.5)4 | V3.10.4.10 | V(4.5)3 | V3.8.5.8 | V(3.4)5 | V4.6.5.6 | V6.8.10 | V3.5.3.4.3.3 | ||||

(5 4 4)

[edit]The (5 4 4) triangle group, Coxeter group [(5,4,4)], orbifold (*544) contains these uniform tilings.

| Uniform (5,4,4) tilings | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [(5,4,4)] (*544) |

[(5,4,4)]+ (544) |

[(5+,4,4)] (5*22) |

[(5,4,1+,4)] (*5222) | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| t0(5,4,4) h{10,4} |

t0,1(5,4,4) r{4,10}1/2 |

t1(5,4,4) h{10,4} |

t1,2(5,4,4) h2{10,4} |

t2(5,4,4) {4,10}1/2 |

t0,2(5,4,4) h2{10,4} |

t0,1,2(5,4,4) t{4,10}1/2 |

s(4,5,4) s{4,10}1/2 |

h(4,5,4) h{4,10}1/2 |

hr(4,5,4) hr{4,10}1/2 | ||

| Uniform duals | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||

| V(4.5)4 | V4.10.4.10 | V(4.5)4 | V4.8.5.8 | V(4.4)5 | V4.8.5.8 | V8.8.10 | V3.4.3.4.3.5 | V1010 | V(4.4.5)2 | ||

(6 3 3)

[edit]The (6 3 3) triangle group, Coxeter group [(6,3,3)], orbifold (*633) contains these uniform tilings.

| Uniform (6,3,3) tilings | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [(6,3,3)], (*633) | [(6,3,3)]+, (633) | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| t0{(6,3,3)} h{12,3} |

t0,1{(6,3,3)} r{3,12}1/2 |

t1{(6,3,3)} h{12,3} |

t1,2{(6,3,3)} h2{12,3} |

t2{(6,3,3)} {3,12}1/2 |

t0,2{(6,3,3)} h2{12,3} |

t0,1,2{(6,3,3)} t{3,12}1/2 |

s{(6,3,3)} s{3,12}1/2 | ||||

| Uniform duals | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| V(3.6)3 | V3.12.3.12 | V(3.6)3 | V3.6.6.6 | V(3.3)6 {12,3} |

V3.6.6.6 | V6.6.12 | V3.3.3.3.3.6 | ||||

(6 4 3)

[edit]The (6 4 3) triangle group, Coxeter group [(6,4,3)], orbifold (*643) contains these uniform tilings.

| (6,4,3) uniform tilings | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [(6,4,3)] (*643) |

[(6,4,3)]+ (643) |

[(6,1+,4,3)] (*3332) |

[(6,4,3+)] (3*32) | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| t0{(6,4,3)} | t0,1{(6,4,3)} | t1{(6,4,3)} | t1,2{(6,4,3)} | t2{(6,4,3)} | t0,2{(6,4,3)} | t0,1,2{(6,4,3)} | s{(6,4,3)} | h{(6,4,3)} | hr{(6,4,3)} |

| Uniform duals | |||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| V(3.6)4 | V3.12.4.12 | V(4.6)3 | V3.8.6.8 | V(3.4)6 | V4.6.6.6 | V6.8.12 | V3.6.3.4.3.3 | V(3.6.6)3 | V4.(3.4)3 |

(6 4 4)

[edit]The (6 4 4) triangle group, Coxeter group [(6,4,4)], orbifold (*644) contains these uniform tilings.

| 6-4-4 uniform tilings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [(6,4,4)], (*644) | (644) | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (6,4,4) h{12,4} |

t0,1(6,4,4) r{4,12}1/2 |

t1(6,4,4) h{12,4} |

t1,2(6,4,4) h2{12,4} |

t2(6,4,4) {4,12}1/2 |

t0,2(6,4,4) h2{12,4} |

t0,1,2(6,4,4) t{4,12}1/2 |

s(6,4,4) s{4,12}1/2 |

| Uniform duals | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| V(4.6)4 | V(4.12)2 | V(4.6)4 | V4.8.6.8 | V412 | V4.8.6.8 | V8.8.12 | V4.6.4.6.6.6 |

Summary of tilings with finite triangular fundamental domains

[edit]Quadrilateral domains

[edit]

(3 2 2 2)

[edit]

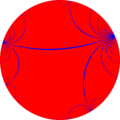

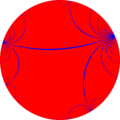

Quadrilateral fundamental domains also exist in the hyperbolic plane, with the *3222 orbifold ([∞,3,∞] Coxeter notation) as the smallest family. There are 9 generation locations for uniform tiling within quadrilateral domains. The vertex figure can be extracted from a fundamental domain as 3 cases (1) Corner (2) Mid-edge, and (3) Center. When generating points are corners adjacent to order-2 corners, degenerate {2} digon faces at those corners exist but can be ignored. Snub and alternated uniform tilings can also be generated (not shown) if a vertex figure contains only even-sided faces.

Coxeter diagrams of quadrilateral domains are treated as a degenerate tetrahedron graph with 2 of 6 edges labeled as infinity, or as dotted lines. A logical requirement of at least one of two parallel mirrors being active limits the uniform cases to 9, and other ringed patterns are not valid.

| Uniform tilings in symmetry *3222 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

(3 2 3 2)

[edit]| Similar H2 tilings in *3232 symmetry | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coxeter diagrams |

||||||||

| Vertex figure |

66 | (3.4.3.4)2 | 3.4.6.6.4 | 6.4.6.4 | ||||

| Image |

|

|

|

| ||||

| Dual |

|

| ||||||

Ideal triangle domains

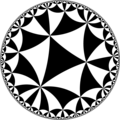

[edit]There are infinitely many triangle group families including infinite orders. This article shows uniform tilings in 9 families: (∞ 3 2), (∞ 4 2), (∞ ∞ 2), (∞ 3 3), (∞ 4 3), (∞ 4 4), (∞ ∞ 3), (∞ ∞ 4), and (∞ ∞ ∞).

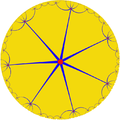

(∞ 3 2)

[edit]The ideal (∞ 3 2) triangle group, Coxeter group [∞,3], orbifold (*∞32) contains these uniform tilings:

| Paracompact uniform tilings in [∞,3] family | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [∞,3], (*∞32) | [∞,3]+ (∞32) |

[1+,∞,3] (*∞33) |

[∞,3+] (3*∞) | |||||||

= |

= |

= |

= | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| {∞,3} | t{∞,3} | r{∞,3} | t{3,∞} | {3,∞} | rr{∞,3} | tr{∞,3} | sr{∞,3} | h{∞,3} | h2{∞,3} | s{3,∞} |

| Uniform duals | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| V∞3 | V3.∞.∞ | V(3.∞)2 | V6.6.∞ | V3∞ | V4.3.4.∞ | V4.6.∞ | V3.3.3.3.∞ | V(3.∞)3 | V3.3.3.3.3.∞ | |

(∞ 4 2)

[edit]The ideal (∞ 4 2) triangle group, Coxeter group [∞,4], orbifold (*∞42) contains these uniform tilings:

| Paracompact uniform tilings in [∞,4] family | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| {∞,4} | t{∞,4} | r{∞,4} | 2t{∞,4}=t{4,∞} | 2r{∞,4}={4,∞} | rr{∞,4} | tr{∞,4} | |

| Dual figures | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| V∞4 | V4.∞.∞ | V(4.∞)2 | V8.8.∞ | V4∞ | V43.∞ | V4.8.∞ | |

| Alternations | |||||||

| [1+,∞,4] (*44∞) |

[∞+,4] (∞*2) |

[∞,1+,4] (*2∞2∞) |

[∞,4+] (4*∞) |

[∞,4,1+] (*∞∞2) |

[(∞,4,2+)] (2*2∞) |

[∞,4]+ (∞42) | |

= |

= |

||||||

| h{∞,4} | s{∞,4} | hr{∞,4} | s{4,∞} | h{4,∞} | hrr{∞,4} | s{∞,4} | |

|

|

|

| ||||

| Alternation duals | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| V(∞.4)4 | V3.(3.∞)2 | V(4.∞.4)2 | V3.∞.(3.4)2 | V∞∞ | V∞.44 | V3.3.4.3.∞ | |

(∞ 5 2)

[edit]The ideal (∞ 5 2) triangle group, Coxeter group [∞,5], orbifold (*∞52) contains these uniform tilings:

| Paracompact uniform apeirogonal/pentagonal tilings | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [∞,5], (*∞52) | [∞,5]+ (∞52) |

[1+,∞,5] (*∞55) |

[∞,5+] (5*∞) | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| {∞,5} | t{∞,5} | r{∞,5} | 2t{∞,5}=t{5,∞} | 2r{∞,5}={5,∞} | rr{∞,5} | tr{∞,5} | sr{∞,5} | h{∞,5} | h2{∞,5} | s{5,∞} | |

| Uniform duals | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| V∞5 | V5.∞.∞ | V5.∞.5.∞ | V∞.10.10 | V5∞ | V4.5.4.∞ | V4.10.∞ | V3.3.5.3.∞ | V(∞.5)5 | V3.5.3.5.3.∞ | ||

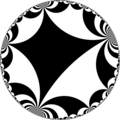

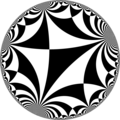

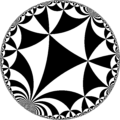

(∞ ∞ 2)

[edit]The ideal (∞ ∞ 2) triangle group, Coxeter group [∞,∞], orbifold (*∞∞2) contains these uniform tilings:

| Paracompact uniform tilings in [∞,∞] family | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

= = |

= = |

= = |

= = |

= = |

= |

= |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| {∞,∞} | t{∞,∞} | r{∞,∞} | 2t{∞,∞}=t{∞,∞} | 2r{∞,∞}={∞,∞} | rr{∞,∞} | tr{∞,∞} |

| Dual tilings | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| V∞∞ | V∞.∞.∞ | V(∞.∞)2 | V∞.∞.∞ | V∞∞ | V4.∞.4.∞ | V4.4.∞ |

| Alternations | ||||||

| [1+,∞,∞] (*∞∞2) |

[∞+,∞] (∞*∞) |

[∞,1+,∞] (*∞∞∞∞) |

[∞,∞+] (∞*∞) |

[∞,∞,1+] (*∞∞2) |

[(∞,∞,2+)] (2*∞∞) |

[∞,∞]+ (2∞∞) |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| h{∞,∞} | s{∞,∞} | hr{∞,∞} | s{∞,∞} | h2{∞,∞} | hrr{∞,∞} | sr{∞,∞} |

| Alternation duals | ||||||

|

|

|

| |||

| V(∞.∞)∞ | V(3.∞)3 | V(∞.4)4 | V(3.∞)3 | V∞∞ | V(4.∞.4)2 | V3.3.∞.3.∞ |

(∞ 3 3)

[edit]The ideal (∞ 3 3) triangle group, Coxeter group [(∞,3,3)], orbifold (*∞33) contains these uniform tilings.

| Paracompact hyperbolic uniform tilings in [(∞,3,3)] family | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [(∞,3,3)], (*∞33) | [(∞,3,3)]+, (∞33) | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| (∞,∞,3) | t0,1(∞,3,3) | t1(∞,3,3) | t1,2(∞,3,3) | t2(∞,3,3) | t0,2(∞,3,3) | t0,1,2(∞,3,3) | s(∞,3,3) | ||||

| Dual tilings | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| V(3.∞)3 | V3.∞.3.∞ | V(3.∞)3 | V3.6.∞.6 | V(3.3)∞ | V3.6.∞.6 | V6.6.∞ | V3.3.3.3.3.∞ | ||||

(∞ 4 3)

[edit]The ideal (∞ 4 3) triangle group, Coxeter group [(∞,4,3)], orbifold (*∞43) contains these uniform tilings:

(∞ 4 4)

[edit]The ideal (∞ 4 4) triangle group, Coxeter group [(∞,4,4)], orbifold (*∞44) contains these uniform tilings.

| Paracompact hyperbolic uniform tilings in [(4,4,∞)] family | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [(4,4,∞)], (*44∞) | (44∞) | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| (4,4,∞) h{∞,4} |

t0,1(4,4,∞) r{4,∞}1/2 |

t1(4,4,∞) h{4,∞}1/2 |

t1,2(4,4,∞) h2{∞,4} |

t2(4,4,∞) {4,∞}1/2 |

t0,2(4,4,∞) h2{∞,4} |

t0,1,2(4,4,∞) t{4,∞}1/2 |

s(4,4,∞) s{4,∞}1/2 | ||||

| Dual tilings | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| V(4.∞)4 | V4.∞.4.∞ | V(4.∞)4 | V4.8.∞.8; | V4∞ | V4.8.∞.8; | V8.8.∞ | V3.4.3.4.3.∞ | ||||

(∞ ∞ 3)

[edit]The ideal (∞ ∞ 3) triangle group, Coxeter group [(∞,∞,3)], orbifold (*∞∞3) contains these uniform tilings.

(∞ ∞ 4)

[edit]The ideal (∞ ∞ 4) triangle group, Coxeter group [(∞,∞,4)], orbifold (*∞∞4) contains these uniform tilings.

(∞ ∞ ∞)

[edit]The ideal (∞ ∞ ∞) triangle group, Coxeter group [(∞,∞,∞)], orbifold (*∞∞∞) contains these uniform tilings.

| Paracompact uniform tilings in [(∞,∞,∞)] family | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (∞,∞,∞) h{∞,∞} |

r(∞,∞,∞) h2{∞,∞} |

(∞,∞,∞) h{∞,∞} |

r(∞,∞,∞) h2{∞,∞} |

(∞,∞,∞) h{∞,∞} |

r(∞,∞,∞) r{∞,∞} |

t(∞,∞,∞) t{∞,∞} |

| Dual tilings | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| V∞∞ | V∞.∞.∞.∞ | V∞∞ | V∞.∞.∞.∞ | V∞∞ | V∞.∞.∞.∞ | V∞.∞.∞ |

| Alternations | ||||||

| [(1+,∞,∞,∞)] (*∞∞∞∞) |

[∞+,∞,∞)] (∞*∞) |

[∞,1+,∞,∞)] (*∞∞∞∞) |

[∞,∞+,∞)] (∞*∞) |

[(∞,∞,∞,1+)] (*∞∞∞∞) |

[(∞,∞,∞+)] (∞*∞) |

[∞,∞,∞)]+ (∞∞∞) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Alternation duals | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| V(∞.∞)∞ | V(∞.4)4 | V(∞.∞)∞ | V(∞.4)4 | V(∞.∞)∞ | V(∞.4)4 | V3.∞.3.∞.3.∞ |

Summary of tilings with infinite triangular fundamental domains

[edit]For a table of all uniform hyperbolic tilings with fundamental domains (p q r), where 2 ≤ p,q,r ≤ 8, and one or more as ∞.

| Infinite triangular hyperbolic tilings | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (p q r) | t0 | h0 | t01 | h01 | t1 | h1 | t12 | h12 | t2 | h2 | t02 | h02 | t012 | s | |||||

(∞ 3 2) |

t0{∞,3} ∞3 |

h0{∞,3} (3.∞)3 |

t01{∞,3} ∞.3.∞ |

t1{∞,3} (3.∞)2 |

t12{∞,3} 6.∞.6 |

h12{∞,3} 3.3.3.∞.3.3 |

t2{∞,3} 3∞ |

t02{∞,3} 3.4.∞.4 |

t012{∞,3} 4.6.∞ |

s{∞,3} 3.3.3.3.∞ | |||||||||

(∞ 4 2) |

t0{∞,4} ∞4 |

h0{∞,4} (4.∞)4 |

t01{∞,4} ∞.4.∞ |

h01{∞,4} 3.∞.3.3.∞ |

t1{∞,4} (4.∞)2 |

h1{∞,4} (4.4.∞)2 |

t12{∞,4} 8.∞.8 |

h12{∞,4} 3.4.3.∞.3.4 |

t2{∞,4} 4∞ |

h2{∞,4} ∞∞ |

t02{∞,4} 4.4.∞.4 |

h02{∞,4} 4.4.4.∞.4 |

t012{∞,4} 4.8.∞ |

s{∞,4} 3.3.4.3.∞ | |||||

(∞ 5 2) |

t0{∞,5} ∞5 |

h0{∞,5} (5.∞)5 |

t01{∞,5} ∞.5.∞ |

t1{∞,5} (5.∞)2 |

t12{∞,5} 10.∞.10 |

h12{∞,5} 3.5.3.∞.3.5 |

t2{∞,5} 5∞ |

t02{∞,5} 5.4.∞.4 |

t012{∞,5} 4.10.∞ |

s{∞,5} 3.3.5.3.∞ | |||||||||

(∞ 6 2) |

t0{∞,6} ∞6 |

h0{∞,6} (6.∞)6 |

t01{∞,6} ∞.6.∞ |

h01{∞,6} 3.∞.3.3.3.∞ |

t1{∞,6} (6.∞)2 |

h1{∞,6} (4.3.4.∞)2 |

t12{∞,6} 12.∞.12 |

h12{∞,6} 3.6.3.∞.3.6 |

t2{∞,6} 6∞ |

h2{∞,6} (∞.3)∞ |

t02{∞,6} 6.4.∞.4 |

h02{∞,6} 4.3.4.4.∞.4 |

t012{∞,6} 4.12.∞ |

s{∞,6} 3.3.6.3.∞ | |||||

(∞ 7 2) |

t0{∞,7} ∞7 |

h0{∞,7} (7.∞)7 |

t01{∞,7} ∞.7.∞ |

t1{∞,7} (7.∞)2 |

t12{∞,7} 14.∞.14 |

h12{∞,7} 3.7.3.∞.3.7 |

t2{∞,7} 7∞ |

t02{∞,7} 7.4.∞.4 |

t012{∞,7} 4.14.∞ |

s{∞,7} 3.3.7.3.∞ | |||||||||

(∞ 8 2) |

t0{∞,8} ∞8 |

h0{∞,8} (8.∞)8 |

t01{∞,8} ∞.8.∞ |

h01{∞,8} 3.∞.3.4.3.∞ |

t1{∞,8} (8.∞)2 |

h1{∞,8} (4.4.4.∞)2 |

t12{∞,8} 16.∞.16 |

h12{∞,8} 3.8.3.∞.3.8 |

t2{∞,8} 8∞ |

h2{∞,8} (∞.4)∞ |

t02{∞,8} 8.4.∞.4 |

h02{∞,8} 4.4.4.4.∞.4 |

t012{∞,8} 4.16.∞ |

s{∞,8} 3.3.8.3.∞ | |||||

(∞ ∞ 2) |

t0{∞,∞} ∞∞ |

h0{∞,∞} (∞.∞)∞ |

t01{∞,∞} ∞.∞.∞ |

h01{∞,∞} 3.∞.3.∞.3.∞ |

t1{∞,∞} ∞4 |

h1{∞,∞} (4.∞)4 |

t12{∞,∞} ∞.∞.∞ |

h12{∞,∞} 3.∞.3.∞.3.∞ |

t2{∞,∞} ∞∞ |

h2{∞,∞} (∞.∞)∞ |

t02{∞,∞} (∞.4)2 |

h02{∞,∞} (4.∞.4)2 |

t012{∞,∞} 4.∞.∞ |

s{∞,∞} 3.3.∞.3.∞ | |||||

(∞ 3 3) |

t0(∞,3,3) (∞.3)3 |

t01(∞,3,3) (3.∞)2 |

t1(∞,3,3) (3.∞)3 |

t12(∞,3,3) 3.6.∞.6 |

t2(∞,3,3) 3∞ |

t02(∞,3,3) 3.6.∞.6 |

t012(∞,3,3) 6.6.∞ |

s(∞,3,3) 3.3.3.3.3.∞ | |||||||||||

(∞ 4 3) |

t0(∞,4,3) (∞.3)4 |

t01(∞,4,3) 3.∞.4.∞ |

t1(∞,4,3) (4.∞)3 |

h1(∞,4,3) (6.6.∞)3 |

t12(∞,4,3) 3.8.∞.8 |

t2(∞,4,3) (4.3)∞ |

t02(∞,4,3) 4.6.∞.6 |

h02(∞,4,3) 4.4.3.4.∞.4.3 |

t012(∞,4,3) 6.8.∞ |

s(∞,4,3) 3.3.3.4.3.∞ | |||||||||

(∞ 5 3) |

t0(∞,5,3) (∞.3)5 |

t01(∞,5,3) 3.∞.5.∞ |

t1(∞,5,3) (5.∞)3 |

t12(∞,5,3) 3.10.∞.10 |

t2(∞,5,3) (5.3)∞ |

t02(∞,5,3) 5.6.∞.6 |

t012(∞,5,3) 6.10.∞ |

s(∞,5,3) 3.3.3.5.3.∞ | |||||||||||

(∞ 6 3) |

t0(∞,6,3) (∞.3)6 |

t01(∞,6,3) 3.∞.6.∞ |

t1(∞,6,3) (6.∞)3 |

h1(∞,6,3) (6.3.6.∞)3 |

t12(∞,6,3) 3.12.∞.12 |

t2(∞,6,3) (6.3)∞ |

t02(∞,6,3) 6.6.∞.6 |

h02(∞,6,3) 4.3.4.3.4.∞.4.3 |

t012(∞,6,3) 6.12.∞ |

s(∞,6,3) 3.3.3.6.3.∞ | |||||||||

(∞ 7 3) |

t0(∞,7,3) (∞.3)7 |

t01(∞,7,3) 3.∞.7.∞ |

t1(∞,7,3) (7.∞)3 |

t12(∞,7,3) 3.14.∞.14 |

t2(∞,7,3) (7.3)∞ |

t02(∞,7,3) 7.6.∞.6 |

t012(∞,7,3) 6.14.∞ |

s(∞,7,3) 3.3.3.7.3.∞ | |||||||||||

(∞ 8 3) |

t0(∞,8,3) (∞.3)8 |

t01(∞,8,3) 3.∞.8.∞ |

t1(∞,8,3) (8.∞)3 |

h1(∞,8,3) (6.4.6.∞)3 |

t12(∞,8,3) 3.16.∞.16 |

t2(∞,8,3) (8.3)∞ |

t02(∞,8,3) 8.6.∞.6 |

h02(∞,8,3) 4.4.4.3.4.∞.4.3 |

t012(∞,8,3) 6.16.∞ |

s(∞,8,3) 3.3.3.8.3.∞ | |||||||||

(∞ ∞ 3) |

t0(∞,∞,3) (∞.3)∞ |

t01(∞,∞,3) 3.∞.∞.∞ |

t1(∞,∞,3) ∞6 |

h1(∞,∞,3) (6.∞)6 |

t12(∞,∞,3) 3.∞.∞.∞ |

t2(∞,∞,3) (∞.3)∞ |

t02(∞,∞,3) (∞.6)2 |

h02(∞,∞,3) (4.∞.4.3)2 |

t012(∞,∞,3) 6.∞.∞ |

s(∞,∞,3) 3.3.3.∞.3.∞ | |||||||||

(∞ 4 4) |

t0(∞,4,4) (∞.4)4 |

h0(∞,4,4) (8.∞.8)4 |

t01(∞,4,4) (4.∞)2 |

h01(∞,4,4) (4.4.∞)2 |

t1(∞,4,4) (4.∞)4 |

h1(∞,4,4) (8.8.∞)4 |

t12(∞,4,4) 4.8.∞.8 |

h12(∞,4,4) 4.4.4.4.∞.4.4 |

t2(∞,4,4) 4∞ |

h2(∞,4,4) ∞∞ |

t02(∞,4,4) 4.8.∞.8 |

h02(∞,4,4) 4.4.4.4.∞.4.4 |

t012(∞,4,4) 8.8.∞ |

s(∞,4,4) 3.4.3.4.3.∞ | |||||

(∞ 5 4) |

t0(∞,5,4) (∞.4)5 |

h0(∞,5,4) (10.∞.10)5 |

t01(∞,5,4) 4.∞.5.∞ |

t1(∞,5,4) (5.∞)4 |

t12(∞,5,4) 4.10.∞.10 |

h12(∞,5,4) 4.4.5.4.∞.4.5 |

t2(∞,5,4) (5.4)∞ |

t02(∞,5,4) 5.8.∞.8 |

t012(∞,5,4) 8.10.∞ |

s(∞,5,4) 3.4.3.5.3.∞ | |||||||||

(∞ 6 4) |

t0(∞,6,4) (∞.4)6 |

h0(∞,6,4) (12.∞.12)6 |

t01(∞,6,4) 4.∞.6.∞ |

h01(∞,6,4) 4.4.∞.4.3.4.∞ |

t1(∞,6,4) (6.∞)4 |

h1(∞,6,4) (8.3.8.∞)4 |

t12(∞,6,4) 4.12.∞.12 |

h12(∞,6,4) 4.4.6.4.∞.4.6 |

t2(∞,6,4) (6.4)∞ |

h2(∞,6,4) (∞.3.∞)∞ |

t02(∞,6,4) 6.8.∞.8 |

h02(∞,6,4) 4.3.4.4.4.∞.4.4 |

t012(∞,6,4) 8.12.∞ |

s(∞,6,4) 3.4.3.6.3.∞ | |||||

(∞ 7 4) |

t0(∞,7,4) (∞.4)7 |

h0(∞,7,4) (14.∞.14)7 |

t01(∞,7,4) 4.∞.7.∞ |

t1(∞,7,4) (7.∞)4 |

t12(∞,7,4) 4.14.∞.14 |

h12(∞,7,4) 4.4.7.4.∞.4.7 |

t2(∞,7,4) (7.4)∞ |

t02(∞,7,4) 7.8.∞.8 |

t012(∞,7,4) 8.14.∞ |

s(∞,7,4) 3.4.3.7.3.∞ | |||||||||

(∞ 8 4) |

t0(∞,8,4) (∞.4)8 |

h0(∞,8,4) (16.∞.16)8 |

t01(∞,8,4) 4.∞.8.∞ |

h01(∞,8,4) 4.4.∞.4.4.4.∞ |

t1(∞,8,4) (8.∞)4 |

h1(∞,8,4) (8.4.8.∞)4 |

t12(∞,8,4) 4.16.∞.16 |

h12(∞,8,4) 4.4.8.4.∞.4.8 |

t2(∞,8,4) (8.4)∞ |

h2(∞,8,4) (∞.4.∞)∞ |

t02(∞,8,4) 8.8.∞.8 |

h02(∞,8,4) 4.4.4.4.4.∞.4.4 |

t012(∞,8,4) 8.16.∞ |

s(∞,8,4) 3.4.3.8.3.∞ | |||||

(∞ ∞ 4) |

t0(∞,∞,4) (∞.4)∞ |

h0(∞,∞,4) (∞.∞.∞)∞ |

t01(∞,∞,4) 4.∞.∞.∞ |

h01(∞,∞,4) 4.4.∞.4.∞.4.∞ |

t1(∞,∞,4) ∞8 |

h1(∞,∞,4) (8.∞)8 |

t12(∞,∞,4) 4.∞.∞.∞ |

h12(∞,∞,4) 4.4.∞.4.∞.4.∞ |

t2(∞,∞,4) (∞.4)∞ |

h2(∞,∞,4) (∞.∞.∞)∞ |

t02(∞,∞,4) (∞.8)2 |

h02(∞,∞,4) (4.∞.4.4)2 |

t012(∞,∞,4) 8.∞.∞ |

s(∞,∞,4) 3.4.3.∞.3.∞ | |||||

(∞ 5 5) |

t0(∞,5,5) (∞.5)5 |

t01(∞,5,5) (5.∞)2 |

t1(∞,5,5) (5.∞)5 |

t12(∞,5,5) 5.10.∞.10 |

t2(∞,5,5) 5∞ |

t02(∞,5,5) 5.10.∞.10 |

t012(∞,5,5) 10.10.∞ |

s(∞,5,5) 3.5.3.5.3.∞ | |||||||||||

(∞ 6 5) |

t0(∞,6,5) (∞.5)6 |

t01(∞,6,5) 5.∞.6.∞ |

t1(∞,6,5) (6.∞)5 |

h1(∞,6,5) (10.3.10.∞)5 |

t12(∞,6,5) 5.12.∞.12 |

t2(∞,6,5) (6.5)∞ |

t02(∞,6,5) 6.10.∞.10 |

h02(∞,6,5) 4.3.4.5.4.∞.4.5 |

t012(∞,6,5) 10.12.∞ |

s(∞,6,5) 3.5.3.6.3.∞ | |||||||||

(∞ 7 5) |

t0(∞,7,5) (∞.5)7 |

t01(∞,7,5) 5.∞.7.∞ |

t1(∞,7,5) (7.∞)5 |

t12(∞,7,5) 5.14.∞.14 |

t2(∞,7,5) (7.5)∞ |

t02(∞,7,5) 7.10.∞.10 |

t012(∞,7,5) 10.14.∞ |

s(∞,7,5) 3.5.3.7.3.∞ | |||||||||||

(∞ 8 5) |

t0(∞,8,5) (∞.5)8 |

t01(∞,8,5) 5.∞.8.∞ |

t1(∞,8,5) (8.∞)5 |

h1(∞,8,5) (10.4.10.∞)5 |

t12(∞,8,5) 5.16.∞.16 |

t2(∞,8,5) (8.5)∞ |

t02(∞,8,5) 8.10.∞.10 |

h02(∞,8,5) 4.4.4.5.4.∞.4.5 |

t012(∞,8,5) 10.16.∞ |

s(∞,8,5) 3.5.3.8.3.∞ | |||||||||

(∞ ∞ 5) |

t0(∞,∞,5) (∞.5)∞ |

t01(∞,∞,5) 5.∞.∞.∞ |

t1(∞,∞,5) ∞10 |

h1(∞,∞,5) (10.∞)10 |

t12(∞,∞,5) 5.∞.∞.∞ |

t2(∞,∞,5) (∞.5)∞ |

t02(∞,∞,5) (∞.10)2 |

h02(∞,∞,5) (4.∞.4.5)2 |

t012(∞,∞,5) 10.∞.∞ |

s(∞,∞,5) 3.5.3.∞.3.∞ | |||||||||

(∞ 6 6) |

t0(∞,6,6) (∞.6)6 |

h0(∞,6,6) (12.∞.12.3)6 |

t01(∞,6,6) (6.∞)2 |

h01(∞,6,6) (4.3.4.∞)2 |

t1(∞,6,6) (6.∞)6 |

h1(∞,6,6) (12.3.12.∞)6 |

t12(∞,6,6) 6.12.∞.12 |

h12(∞,6,6) 4.3.4.6.4.∞.4.6 |

t2(∞,6,6) 6∞ |

h2(∞,6,6) (∞.3)∞ |

t02(∞,6,6) 6.12.∞.12 |

h02(∞,6,6) 4.3.4.6.4.∞.4.6 |

t012(∞,6,6) 12.12.∞ |

s(∞,6,6) 3.6.3.6.3.∞ | |||||

(∞ 7 6) |

t0(∞,7,6) (∞.6)7 |

h0(∞,7,6) (14.∞.14.3)7 |

t01(∞,7,6) 6.∞.7.∞ |

t1(∞,7,6) (7.∞)6 |

t12(∞,7,6) 6.14.∞.14 |

h12(∞,7,6) 4.3.4.7.4.∞.4.7 |

t2(∞,7,6) (7.6)∞ |

t02(∞,7,6) 7.12.∞.12 |

t012(∞,7,6) 12.14.∞ |

s(∞,7,6) 3.6.3.7.3.∞ | |||||||||

(∞ 8 6) |

t0(∞,8,6) (∞.6)8 |

h0(∞,8,6) (16.∞.16.3)8 |

t01(∞,8,6) 6.∞.8.∞ |

h01(∞,8,6) 4.3.4.∞.4.4.4.∞ |

t1(∞,8,6) (8.∞)6 |

h1(∞,8,6) (12.4.12.∞)6 |

t12(∞,8,6) 6.16.∞.16 |

h12(∞,8,6) 4.3.4.8.4.∞.4.8 |

t2(∞,8,6) (8.6)∞ |

h2(∞,8,6) (∞.4.∞.3)∞ |

t02(∞,8,6) 8.12.∞.12 |

h02(∞,8,6) 4.4.4.6.4.∞.4.6 |

t012(∞,8,6) 12.16.∞ |

s(∞,8,6) 3.6.3.8.3.∞ | |||||

(∞ ∞ 6) |

t0(∞,∞,6) (∞.6)∞ |

h0(∞,∞,6) (∞.∞.∞.3)∞ |

t01(∞,∞,6) 6.∞.∞.∞ |

h01(∞,∞,6) 4.3.4.∞.4.∞.4.∞ |

t1(∞,∞,6) ∞12 |

h1(∞,∞,6) (12.∞)12 |

t12(∞,∞,6) 6.∞.∞.∞ |

h12(∞,∞,6) 4.3.4.∞.4.∞.4.∞ |

t2(∞,∞,6) (∞.6)∞ |

h2(∞,∞,6) (∞.∞.∞.3)∞ |

t02(∞,∞,6) (∞.12)2 |

h02(∞,∞,6) (4.∞.4.6)2 |

t012(∞,∞,6) 12.∞.∞ |

s(∞,∞,6) 3.6.3.∞.3.∞ | |||||

(∞ 7 7) |

t0(∞,7,7) (∞.7)7 |

t01(∞,7,7) (7.∞)2 |

t1(∞,7,7) (7.∞)7 |

t12(∞,7,7) 7.14.∞.14 |

t2(∞,7,7) 7∞ |

t02(∞,7,7) 7.14.∞.14 |

t012(∞,7,7) 14.14.∞ |

s(∞,7,7) 3.7.3.7.3.∞ | |||||||||||

(∞ 8 7) |

t0(∞,8,7) (∞.7)8 |

t01(∞,8,7) 7.∞.8.∞ |

t1(∞,8,7) (8.∞)7 |

h1(∞,8,7) (14.4.14.∞)7 |

t12(∞,8,7) 7.16.∞.16 |

t2(∞,8,7) (8.7)∞ |

t02(∞,8,7) 8.14.∞.14 |

h02(∞,8,7) 4.4.4.7.4.∞.4.7 |

t012(∞,8,7) 14.16.∞ |

s(∞,8,7) 3.7.3.8.3.∞ | |||||||||

(∞ ∞ 7) |

t0(∞,∞,7) (∞.7)∞ |

t01(∞,∞,7) 7.∞.∞.∞ |

t1(∞,∞,7) ∞14 |

h1(∞,∞,7) (14.∞)14 |

t12(∞,∞,7) 7.∞.∞.∞ |

t2(∞,∞,7) (∞.7)∞ |

t02(∞,∞,7) (∞.14)2 |

h02(∞,∞,7) (4.∞.4.7)2 |

t012(∞,∞,7) 14.∞.∞ |

s(∞,∞,7) 3.7.3.∞.3.∞ | |||||||||

(∞ 8 8) |

t0(∞,8,8) (∞.8)8 |

h0(∞,8,8) (16.∞.16.4)8 |

t01(∞,8,8) (8.∞)2 |

h01(∞,8,8) (4.4.4.∞)2 |

t1(∞,8,8) (8.∞)8 |

h1(∞,8,8) (16.4.16.∞)8 |

t12(∞,8,8) 8.16.∞.16 |

h12(∞,8,8) 4.4.4.8.4.∞.4.8 |

t2(∞,8,8) 8∞ |

h2(∞,8,8) (∞.4)∞ |

t02(∞,8,8) 8.16.∞.16 |

h02(∞,8,8) 4.4.4.8.4.∞.4.8 |

t012(∞,8,8) 16.16.∞ |

s(∞,8,8) 3.8.3.8.3.∞ | |||||

(∞ ∞ 8) |

t0(∞,∞,8) (∞.8)∞ |

h0(∞,∞,8) (∞.∞.∞.4)∞ |

t01(∞,∞,8) 8.∞.∞.∞ |

h01(∞,∞,8) 4.4.4.∞.4.∞.4.∞ |

t1(∞,∞,8) ∞16 |

h1(∞,∞,8) (16.∞)16 |

t12(∞,∞,8) 8.∞.∞.∞ |

h12(∞,∞,8) 4.4.4.∞.4.∞.4.∞ |

t2(∞,∞,8) (∞.8)∞ |

h2(∞,∞,8) (∞.∞.∞.4)∞ |

t02(∞,∞,8) (∞.16)2 |

h02(∞,∞,8) (4.∞.4.8)2 |

t012(∞,∞,8) 16.∞.∞ |

s(∞,∞,8) 3.8.3.∞.3.∞ | |||||

(∞ ∞ ∞) |

t0(∞,∞,∞) ∞∞ |

h0(∞,∞,∞) (∞.∞)∞ |

t01(∞,∞,∞) (∞.∞)2 |

h01(∞,∞,∞) (4.∞.4.∞)2 |

t1(∞,∞,∞) ∞∞ |

h1(∞,∞,∞) (∞.∞)∞ |

t12(∞,∞,∞) (∞.∞)2 |

h12(∞,∞,∞) (4.∞.4.∞)2 |

t2(∞,∞,∞) ∞∞ |

h2(∞,∞,∞) (∞.∞)∞ |

t02(∞,∞,∞) (∞.∞)2 |

h02(∞,∞,∞) (4.∞.4.∞)2 |

t012(∞,∞,∞) ∞3 |

s(∞,∞,∞) (3.∞)3 | |||||

References

[edit]- John Horton Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strauss, The Symmetries of Things 2008, ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5 (Chapter 19, The Hyperbolic Archimedean Tessellations)

External links

[edit]- Hatch, Don. "Hyperbolic Planar Tessellations". Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- Eppstein, David. "The Geometry Junkyard: Hyperbolic Tiling". Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- Joyce, David. "Hyperbolic Tessellations". Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- Klitzing, Richard. "2D Tesselations Hyperbolic Tesselations".

- The EPINET project explores 2D hyperbolic (H²) tilings

Uniform tilings in hyperbolic plane

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Hyperbolic plane basics

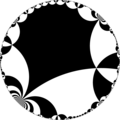

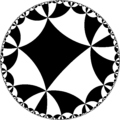

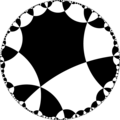

Hyperbolic geometry is a non-Euclidean geometry in which the parallel postulate of Euclidean geometry fails, allowing for infinitely many lines through a given point not on a line that do not intersect the line.[3] This contrasts with Euclidean geometry, where exactly one parallel exists, and elliptic geometry, where none do. The geometry was discovered independently by Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky, who published his work in 1829, and János Bolyai, who published in 1832 as an appendix to his father's book.[4] Henri Poincaré formalized key aspects in the late 19th century, particularly through analytic models that embedded hyperbolic geometry within Euclidean space, enabling rigorous study.[5] Several models represent the hyperbolic plane, each preserving its intrinsic properties while using familiar Euclidean constructs. The Poincaré disk model maps the hyperbolic plane to the open unit disk in the complex plane, where points are interior points with and , and the hyperbolic distance is given by [6] Hyperbolic lines appear as circular arcs orthogonal to the boundary circle. The Klein-Beltrami model, also within the unit disk, uses straight Euclidean chords as lines but distorts angles, making it useful for projective properties.[7] The upper half-plane model places the hyperbolic plane in the set of complex numbers with positive imaginary part, where lines are vertical rays or semicircles orthogonal to the real axis, facilitating computations in complex analysis.[8] In hyperbolic geometry, the sum of the interior angles of any triangle is less than radians (180 degrees), with the difference known as the angular defect. The area of a hyperbolic triangle is equal to its defect, so for angles , , and , assuming the Gaussian curvature is .[9] This proportionality highlights the negative curvature of the space. The hyperbolic plane has infinite extent, but unlike the Euclidean plane where the area of a disk grows quadratically with radius (as ), hyperbolic area grows exponentially: the area of a disk of radius is , which asymptotically behaves as for large .[6] This exponential growth accommodates denser tilings at greater distances, distinguishing hyperbolic space fundamentally from Euclidean.Uniform tilings definition

Uniform tilings in the hyperbolic plane are edge-to-edge tessellations composed of regular geodesic polygons as faces, with the key property that the tiling is vertex-transitive—all vertices are equivalent under the symmetries of the tiling, meaning the arrangement of polygons meeting at each vertex is identical.[10] This distinguishes them from more general tessellations, which may lack vertex-transitivity or use irregular polygons. Among uniform tilings, subtypes include regular tilings, denoted by the Schläfli symbol , where all faces are identical regular -gons and exactly such polygons meet at each vertex; these are fully transitive on both faces and vertices. Semiregular or Archimedean uniform tilings feature regular polygonal faces of two or more types but maintain uniform vertex configurations, ensuring vertex-transitivity while allowing variety in face shapes around each vertex.[10] In the hyperbolic plane, regular uniform tilings exist whenever , , and , a condition that yields infinitely many such tilings due to the negative curvature allowing smaller interior angles than in Euclidean geometry. The vertex figure of a regular tiling is itself a regular -gon, formed by connecting the midpoints of edges incident to a vertex. Overall, there are infinitely many uniform tilings, though systematic enumerations often focus on those generated by the Wythoff construction, which produces principal classes cataloged in finite lists for practical study. Key properties of these tilings include the fact that at least three polygons meet at each vertex, as the hyperbolic metric permits angle deficits that accommodate higher coordination without overlap or gaps. Unlike Euclidean tilings, hyperbolic uniform tilings exhibit exponential growth in the number of tiles with distance from a fixed point, reflecting the plane's constant negative curvature and unique density characteristics. The hyperbolic plane's failure of the Euclidean parallel postulate enables this abundance of tilings beyond what is possible in flat space.[11]Construction Methods

Wythoff construction

The Wythoff construction provides a systematic approach to generating uniform tilings in the hyperbolic plane from the symmetry groups defined by Coxeter diagrams, extending the method originally developed for uniform polyhedra and Euclidean tilings. Named after Dutch mathematician Willem Abraham Wythoff, who introduced the core idea in his 1918 paper exploring relations among polytopes in the 600-cell family, the construction was later generalized by H.S.M. Coxeter to higher dimensions and non-Euclidean geometries, including the hyperbolic plane.[12][13] In this framework, uniform tilings—characterized by vertex-transitivity and regular polygonal faces—emerge as orbits under the action of a Coxeter group generated by reflections across the sides of a fundamental triangle. The process begins with a fundamental triangle in the hyperbolic plane, bounded by three mirrors corresponding to the Coxeter group's generators, with interior angles , , and where are integers satisfying to ensure hyperbolicity. Reflections across these mirrors tile the plane, and the Wythoff construction selects a generator point within or on the boundary of this triangle to produce vertex orbits via the full group action, including compositions that yield rotations. The three canonical uniform tilings arise from distinct placements of the generator point relative to the mirrors, denoted by Wythoff symbols: positions the point at the vertex opposite the -mirror (activating rotations around that vertex); places it on the -mirror, equidistant from the - and -mirrors; and situates it at the intersection of the - and -mirrors. These orbits define the vertices, with edges and faces formed by connecting nearest images under adjacent reflections, ensuring the resulting tiling is uniform.[14][15] Mathematically, the construction yields isohedral tilings where the symmetry group acts transitively on vertices, with the active rotations around the fundamental triangle's vertices producing the vertex figures of the tiling. This rotational aspect distinguishes it from pure reflective generations, and the barred symbol in Wythoff notation often aligns with Petrie paths—skew polygons that traverse the tiling by alternating left and right turns across edges, linking faces in a helical manner without closing prematurely. In the Poincaré disk model, vertex positions can be computed by applying the Möbius transformations representing the Coxeter group elements to an initial generator point inside the unit disk, yielding coordinates for group elements , where distances are preserved via the hyperbolic metric . This generates all uniform tilings with triangular fundamental domains, including those with right angles (e.g., ) and many others beyond regular cases, while extending Euclidean analogs like the snub trihexagonal tiling.[16][17][18]Kaleidoscopic construction

The kaleidoscopic construction generates uniform tilings of the hyperbolic plane through successive reflections of a fundamental polygonal domain across its sides, producing a tessellation that fills the space edge-to-edge without gaps or overlaps. This method relies on discrete reflection groups, whose structure is encoded by Coxeter-Dynkin diagrams specifying the angles between reflecting mirrors. The fundamental domain is typically a triangle or quadrilateral with right angles or multiples of (where is an integer), ensuring the group's action yields uniform polyhedra meeting at each vertex. Unlike rotational constructions, this approach emphasizes the full symmetry of the reflection group, generating both the tiling and its dual simultaneously.[19] For triangular domains, the fundamental triangle has interior angles , , and , where are integers satisfying , which guarantees hyperbolic geometry as the angle sum is less than . Reflections across the three sides generate the triangular group, denoted in Coxeter notation as , whose orbits tile the plane with regular polygons arranged according to the vertex figure defined by the diagram. The resulting tessellation is uniform because the group acts transitively on the vertices, edges, and faces, with the domain's replication producing all tiles via isometries. This construction, rooted in the theory of Coxeter groups, systematically enumerates infinite families of such tilings.[20][21] Quadrilateral domains extend the method for certain uniform tilings, featuring angles , , , and , where satisfy conditions ensuring the total angle sum is less than , such as . Reflections across the four sides generate a quadrilateral group, often represented by a branched Coxeter diagram, leading to tilings with a mix of regular polygons like squares and higher-sided figures. The side lengths are determined hyperbolically to maintain right angles at alternate vertices, with the group's action ensuring vertex-transitivity.[21] In ideal cases, one or more vertices of the fundamental domain approach infinity, resulting in zero angles and ideal points on the boundary of the hyperbolic disk model, or equivalently, horocycles in the upper half-plane model. These configurations produce uniform tilings with infinite-sided apeirogons or horocyclic tiles, still governed by the same reflection principles but with parabolic elements in the group. The kaleidoscopic replication covers the hyperbolic plane completely, distinguishing this full reflective approach from rotational subgroups like those in Wythoff constructions, which generate subsets of the symmetries.[19][21]Right Triangle Domain Tilings

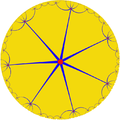

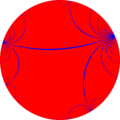

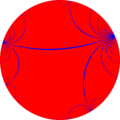

Regular hyperbolic tilings

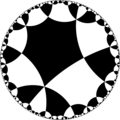

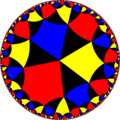

Regular hyperbolic tilings, denoted by the Schläfli symbol {p, q}, consist of congruent regular -gons meeting at each vertex, where are integers satisfying .[22][23] This condition ensures the tilings exist in the hyperbolic plane, distinguishing them from the finite spherical cases where and the three Euclidean cases where equality holds.[10] The interior angle of each regular -gon in such a tiling is .[10] These tilings arise from the action of the infinite Coxeter group on the hyperbolic plane, generated by reflections across the sides of a fundamental domain that is a right hyperbolic triangle with angles , , and .[10] This domain corresponds to the (oriented) triangle group , and the full symmetry group is a discrete subgroup of the isometry group of the hyperbolic plane, rendering the tilings non-compact with infinite extent.[10] The dual of a tiling is the tiling, obtained by interchanging the roles of faces and vertices.[10] There are infinitely many such tilings, organized into families such as the triangular tilings for , where regular triangles meet at each vertex; the hexagonal tilings for , with three -gons at each vertex; the square-based tilings for ; and the pentagonal tilings for .[22][10] As increases within a family, the vertex density grows, leading to increasingly crowded configurations around each vertex.[23] Representative examples include the triheptagonal tiling, in which seven equilateral triangles meet at each vertex; the trioctagonal tiling, with eight triangles per vertex; the heptagonal tiling, featuring three regular heptagons at each vertex; and the pentagonal tiling, with four regular pentagons meeting at each vertex.[10][22] These regular tilings form the basis for uniform tilings generated via the Wythoff construction in specific cases, such as for triangular families.[10](7 3 2) tiling

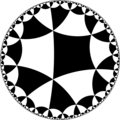

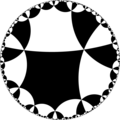

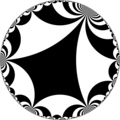

The (7 3 2) tiling, also denoted by the vertex configuration 3.7.3, is a uniform semiregular tiling of the hyperbolic plane in which regular triangles and regular heptagons alternate around each vertex, with two triangles and one heptagon meeting at every vertex. This configuration ensures vertex-transitivity, meaning the tiling looks the same from any vertex, and all edges are of equal length. The tiling is constructed using the kaleidoscopic method based on a right-angled fundamental triangle with interior angles , , and , corresponding to the Wythoff symbol . Reflections across the sides of this triangle generate the full symmetry group, producing the alternating pattern of triangular and heptagonal faces without cusps, as all angles are finite. Key properties include regular polygonal faces—equilateral triangles and regular heptagons—with exactly three tiles meeting at each vertex, confirming its uniform nature and hyperbolic density. The hyperbolicity is verified by the angle sum of the fundamental triangle: . The symmetry group is the Coxeter triangle group , which acts transitively on the vertices. In the Poincaré disk model, the tiling appears with centers of polygons radiating outward from a central vertex, edges remaining equal in length but appearing to converge toward the boundary due to the conformal projection. This tiling holds historical significance as the first semiregular hyperbolic uniform tiling enumerated in systematic classifications, arising as the rectification of the regular {3,7} triangular tiling.(8 3 2) tiling

The (8 3 2) tiling, also known as the trioctagonal tiling with vertex configuration 3.8.3, consists of regular triangles and regular octagons meeting alternately such that two triangles and one octagon adjoin at each vertex.[1] This configuration arises as one of the seven uniform tilings in the symmetry family generated by the triangle group with angles π/3, π/8, and π/2. It is constructed via the Wythoff construction applied to the right-angled hyperbolic triangle with angles π/3, π/8, and π/2, using the symbol 3 | 8 2, where reflections across the sides of this fundamental domain generate the full tiling through kaleidoscopic replication.[24] The resulting structure features equal edge lengths between all adjacent polygons, with exactly three faces meeting at every vertex, ensuring vertex-transitivity and uniformity across the infinite expanse of the hyperbolic plane.[1] In the Poincaré disk model, this tiling exhibits octagons that progressively enlarge toward the boundary, illustrating the expansive nature of hyperbolic space, while triangles maintain consistent proportions relative to their local curvature.[25] The hyperbolic area of individual tiles can be computed from the angular defect of the fundamental domain triangle, which has area π/24, providing a measure of the tiling's density and the contribution of each polygon to the overall geometry.[26] This tiling shares structural similarities with the (7 3 2) tiling but incorporates octagons in place of heptagons, resulting in heightened rotational symmetry at the octagonal vertices.[1](5 4 2) tiling

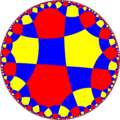

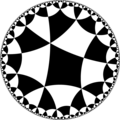

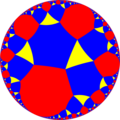

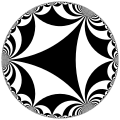

The (5 4 2) tiling, also denoted by the vertex configuration 4.5.4, is a uniform tiling of the hyperbolic plane composed of regular squares and pentagons arranged such that squares and pentagons alternate around each vertex.[10] This semi-regular tessellation features two squares and one pentagon meeting at every vertex in the cyclic order square-pentagon-square, ensuring all edges are of equal length and all interior angles are equal within each face type.[10] The tiling arises from the kaleidoscopic construction using a right-angled hyperbolic triangle as the fundamental domain, with vertex angles , , and . In Wythoff notation, it corresponds to the symbol , where reflections across the sides of this domain generate the full symmetry group, producing the alternating pattern of compact square and pentagonal faces. The area of this fundamental domain, computed via the hyperbolic excess formula, is . As a vertex-transitive tiling, the (5 4 2) configuration exhibits full symmetry under the action of its automorphism group, with no irregularities in vertex environments.[10] It was among the earliest uniform hyperbolic tilings enumerated by H.S.M. Coxeter in his foundational work on discrete groups and tessellations. The tiling serves as a canonical example in orbifold theory, illustrating the quotient space formed by its symmetry group acting on the hyperbolic plane.[27] In visualizations such as the Klein model, the vertices appear as symmetric rosettes, highlighting the tiling's radial symmetry and infinite extent.(6 4 2) tiling

The (6 4 2) tiling, also known as the 6.4.2 tiling, is a uniform hyperbolic tiling featuring an alternating arrangement of regular hexagons, squares, and digons meeting three at each vertex. This vertex configuration ensures vertex-transitivity, with the symmetry group acting uniformly across all vertices. The inclusion of digons, which are 2-gons with interior angles of π, allows the tiling to fit the hyperbolic metric while maintaining edge-to-edge regularity.[28] The tiling is constructed via the kaleidoscopic method, reflecting a fundamental right-angled hyperbolic triangle with interior angles , , and across its sides to generate the full pattern. This process, rooted in the Wythoff construction, positions the generating vertex along the appropriate branch of the triangle's altitude corresponding to the symbol 4 | 6 2, producing the specific 6.4.2 arrangement from the broader family of [4,6] symmetries. The resulting structure fills the hyperbolic plane completely, with the negative curvature preventing overlaps and enabling boundless extension.[29] In visualizations using the Poincaré disk model, the hexagons and squares appear increasingly distorted and elongated toward the disk's boundary, radiating outward in a pattern that emphasizes the hyperbolic geometry's exponential growth. The full symmetry group is the Coxeter group [4,6], equivalent to the (2,4,6) triangle group with orbifold notation *642, generated by reflections satisfying relations . This tiling has inspired artistic explorations of hyperbolic patterns, akin to M.C. Escher's woodcuts, through colored variants that highlight subgroup symmetries.[28][29](7 4 2) tiling

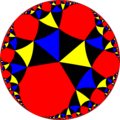

The (7 4 2) tiling, also denoted as 7.4.2, is a uniform tiling of the hyperbolic plane featuring regular heptagons, squares, and digons arranged around each vertex in that cyclic order.[1] It is constructed via the Wythoff method applied to the fundamental domain of a right-angled hyperbolic triangle with angles π/7, π/4, and π/2, corresponding to the triangle group Δ(2,4,7).[30] The Wythoff symbol is 4 | 7 2, where the bar indicates the position of the original vertex relative to the mirrors of the domain, generating the tiling by reflections and identifying orbits of vertices, edges, and faces.[10] Key properties include a triangular vertex figure, with all edges of equal length due to the uniformity, and a vertex degree of 3, making it vertex-transitive under the action of its symmetry group [7,4] (*742).[1] Compared to tilings with lower-order polygons like hexagons, this arrangement exhibits higher density in the sense of greater angular deficit at vertices, emphasizing the hyperbolic curvature.[1] This tiling was among those enumerated by H.S.M. Coxeter in his classification of regular and uniform tessellations of non-Euclidean spaces.[31] In visualizations using the Poincaré disk model, the heptagons interlock with adjacent squares, while digons manifest as lens-shaped regions between them, producing a radiating pattern that fills the disk with increasing crowding toward the boundary.[25](8 4 2) tiling

The (8 4 2) tiling, also denoted by its vertex configuration 4.8.4, is a uniform tiling of the hyperbolic plane in which regular squares and octagons meet such that two squares and one octagon surround each vertex.[25] This arrangement ensures vertex-transitivity, with all edges of equal length and faces being regular polygons.[10] The tiling arises from the Wythoff construction applied to a right-angled hyperbolic triangle with interior angles , , and , using the symbol .[10] This method generates the tiling by reflecting a generator point across the triangle's sides, producing the full tessellation through the action of the associated Coxeter group .[25] Each vertex in the resulting structure is 3-valent, and the tiling is infinite yet locally finite, covering the hyperbolic plane without gaps or overlaps.[10] In the Poincaré disk model, visualizations reveal progressively larger octagons in the outer rings approaching the disk's boundary, highlighting the expansive nature of hyperbolic geometry.[25] A distinctive feature is the tiling's boundary behavior when projected to compact quotients by Fuchsian groups, where the mirrors of the fundamental domain induce boundaries on the resulting finite hyperbolic surfaces.[10](5 5 2) tiling

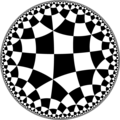

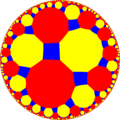

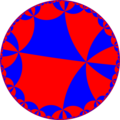

The (5 5 2) tiling, also known as the 5.5.4 tiling or bilateral pentagonal tiling, is a uniform tiling of the hyperbolic plane composed of regular pentagons and squares, with exactly two pentagons and one square incident to each vertex. This arrangement arises from the vertex configuration 5.5.4, where the faces alternate in a symmetric pattern around vertices, forming symmetric pentagonal rosettes that highlight the bilateral nature of the layout. The tiling is generated via the Wythoff construction applied to an isosceles right triangle with interior angles , , and , corresponding to the Wythoff symbol . This fundamental domain reflects the symmetry group of the tiling, where the equal acute angles lead to the repeated pentagonal faces in the construction, marking it as the first such right-triangle-based uniform hyperbolic tiling with duplicated face types in its domain. As a Wythoffian uniform tiling, it is vertex-transitive, meaning the symmetry group acts transitively on its vertices, ensuring all vertices are equivalent under the tiling's isometries. Chiral pairs of this tiling exist, corresponding to left-handed and right-handed enantiomorphic forms that are mirror images but not superimposable, arising from the bilateral symmetry in the isosceles domain.(6 5 2) tiling

The (6 5 2) tiling, also denoted by the vertex configuration 4.5.6, is a uniform tiling of the hyperbolic plane in which regular squares, pentagons, and hexagons meet in that cyclic order at each vertex. This arrangement arises from the kaleidoscopic construction using a right-angled hyperbolic triangle with interior angles , , and . The Wythoff symbol for this tiling is 5 | 6 2, indicating the placement of the generating vertex near the angle in the fundamental domain. Reflections across the triangle's sides generate the full symmetry group, producing an edge-to-edge tiling that is vertex-transitive.[32][2] The tiling features three distinct face types: squares corresponding to the right angle, pentagons linked to the angle, and hexagons associated with the angle. This diversity introduces higher complexity compared to tilings with fewer face types, such as the (5 5 2) configuration, as the varying side lengths and angles require precise hyperbolic trigonometry to ensure compatibility; for instance, edge lengths are computed using formulas involving inverse hyperbolic cosines based on the cosine of half-angles in the fundamental triangle. The resulting structure exhibits interwoven polygons that create a dense, non-periodic pattern when visualized in models like the Poincaré disk, where curvature allows more than six polygons to surround a vertex without overlap.[2][32] Due to its mix of squares, pentagons, and hexagons, the (6 5 2) tiling has been explored in designs mimicking soccer ball patterns adapted to hyperbolic geometry, offering aesthetic and structural inspiration for curved-surface models beyond traditional spherical polyhedra.[2](6 6 2) tiling

The (6 6 2) tiling, denoted alternatively as 6.6.4, is a uniform tiling of the hyperbolic plane featuring the vertex configuration consisting of two regular hexagons and one regular square meeting at each vertex. This arrangement ensures that the tiling is vertex-transitive, with all vertices equivalent under the symmetry group, and employs congruent regular polygons throughout.[2] The tiling arises from the triangle group (6 6 2), corresponding to reflections across the sides of an isosceles hyperbolic triangle with interior angles , , and . This fundamental domain generates the full symmetry group via reflections, enabling the Wythoff construction with symbol , where the inactive mirror is the first (associated with the angle), and the active mirrors correspond to the remaining angles, producing the bilateral hexagonal pattern of hexagons separated by squares.[32][2] In visualizations using the Poincaré disk model, the tiling exhibits radial symmetry, with polygons appearing as circular arcs orthogonal to the boundary circle, and the central region approximating a Euclidean hexagonal tiling due to locally reduced curvature near the disk's origin.[32][2] This central approximation highlights the tiling's transition from near-Euclidean behavior at the core to distinctly hyperbolic expansion outward. Similar to the (5 5 2) tiling, it belongs to the family of right triangle domain tilings but features hexagonal rather than pentagonal elements.[2](8 6 2) tiling

The (8 6 2) tiling is a uniform tiling of the hyperbolic plane in which regular octagons, regular hexagons, and regular squares meet at each vertex in the sequence 8.6.4. This vertex configuration ensures edge-to-edge filling with vertex-transitive symmetry, where all vertices are equivalent under the tiling's symmetry group. The notation (8 6 2) derives from the underlying Coxeter group [8,6], while the alternative designation 4.6.8 reflects the polygon sides around the vertex.[2] The tiling is generated from a fundamental domain consisting of a right-angled hyperbolic triangle with interior angles π/8, π/6, and π/2. Reflections across the triangle's sides produce the full symmetry group, and the Wythoff construction with symbol 6 | 8 2 yields the specific arrangement of octagons, hexagons, and squares by selecting points on the triangle's branches corresponding to these orders. This method systematically derives the tiling from the triangle group's action, ensuring uniform edge lengths and angles.[33][2] In visualizations using the Poincaré disk model, the (8 6 2) tiling displays a layered structure, with central tiles appearing smaller and successive rings of polygons growing larger toward the boundary, illustrating the expansive nature of hyperbolic space. This outward expansion highlights the tiling's adaptation to negative curvature, where the sum of angles at each vertex exceeds 360 degrees in Euclidean measure but fits exactly in hyperbolic geometry. The tiling was notably rare in early enumerations of uniform hyperbolic tilings and was incorporated into comprehensive lists by H.S.M. Coxeter through his systematic study of reflection groups and their generated patterns.[2][31](7 7 2) tiling