Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Aboriginal title

View on Wikipedia

Aboriginal title is a common law doctrine that the land rights of indigenous peoples to customary tenure persist after the assumption of sovereignty to that land by another colonising state. The requirements of proof for the recognition of aboriginal title, the content of aboriginal title, the methods of extinguishing aboriginal title, and the availability of compensation in the case of extinguishment vary significantly by jurisdiction. Nearly all jurisdictions are in agreement that aboriginal title is inalienable, and that it may be held either individually or collectively.

Aboriginal title is also referred to as indigenous title, native title (in Australia), original Indian title (in the United States), and customary title (in New Zealand). Aboriginal title jurisprudence is related to indigenous rights, influencing and influenced by non-land issues, such as whether the government owes a fiduciary duty to indigenous peoples. While the judge-made doctrine arises from customary international law, it has been codified nationally by legislation, treaties, and constitutions.

Aboriginal title was first acknowledged in the early 19th century, in decisions in which indigenous peoples were not a party. Significant aboriginal title litigation resulting in victories for indigenous peoples did not arise until recent decades. The majority of court cases have been litigated in Australia, Canada, Malaysia, New Zealand, and the United States. Aboriginal title is an important area of comparative law, with many cases being cited as persuasive authority across jurisdictions. Legislated Indigenous land rights often follow from the recognition of native title.

British colonial legacy

[edit]

Aboriginal title arose at the intersection of three common law doctrines articulated by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council: the Act of State doctrine, the Doctrine of Continuity, and the Recognition Doctrine.[1] The Act of State doctrine held that the Crown could confiscate or extinguish real or personal property rights in the process of conquering, without scrutiny from any British court, but could not perpetrate an Act of State against its own subjects.[1] The Doctrine of Continuity presumed that the Crown did not intend to extinguish private property upon acquiring sovereignty, and thus that pre-existing interests were enforceable under British law.[1] Its mirror was the Recognition Doctrine, which held that private property rights were presumed to be extinguished in the absence of explicit recognition.[1]

In 1608, the same year in which the Doctrine of Continuity emerged,[2][3] Edward Coke delivered a famous dictum in Calvin's Case (1608) that the laws of all non-Christians would be abrogated upon their conquest.[4] Coke's view was not put into practice, but was rejected by Lord Mansfield in 1774.[5] The two doctrines were reconciled, with the Doctrine of Continuity prevailing in nearly all situations (except, for example, public property of the predecessor state) in Oyekan v Adele (1957).[6]

The first Indigenous land rights case under the common law, Mohegan Indians v. Connecticut, was litigated from 1705 to 1773, with the Privy Council affirming without opinion the judgement of a non-judicial tribunal.[7][n 1] Other important Privy Council decisions include In re Southern Rhodesia (1919)[8] rejected a claim for aboriginal title, writing that:

Some tribes are so low in the scale of social organization that their usages and conceptions of rights and duties are not to be reconciled with the institutions or the legal ideas of civilized society. Such a gulf cannot be bridged.[9]

Amodu Tijani v. Southern Nigeria (Secretary) (1921).[10] laid the basis for several elements of the modern aboriginal title doctrine, upholding a customary land claim and urging the need to "study of the history of the particular community and its usages in each case."[10] Subsequently, the Privy Council issued many opinions confirming the existence of aboriginal title, and upholding customary land claims; many of these arose in African colonies.[11] Modern decisions have heaped criticism upon the views expressed in Southern Rhodesia.[12]

Doctrinal overview

[edit]Recognition

[edit]The requirements for establishing an aboriginal title to the land vary across countries, but generally speaking, the aboriginal claimant must establish (exclusive) occupation (or possession) from a long time ago, generally before the assertion of sovereignty, and continuity to the present day.

Content

[edit]Aboriginal title does not constitute allodial title or radical title in any jurisdiction. Instead, its content is generally described as a usufruct, i.e. a right to use, although in practice this may mean anything from a right to use land for specific, enumerated purposes, or a general right to use which approximates fee simple.

It is common ground among the relevant jurisdictions that aboriginal title is inalienable, in the sense that it cannot be transferred except to the general government (known, in many of the relevant jurisdictions, as "the Crown")—although Malaysia allows aboriginal title to be sold between indigenous peoples, unless contrary to customary law. Especially in Australia, the content of aboriginal title varies with the degree to which claimants are able to satisfy the standard of proof for recognition. In particular, the content of aboriginal title may be tied to the traditions and customs of the indigenous peoples, and only accommodate growth and change to a limited extent.

Extinguishment

[edit]Aboriginal title can be extinguished by the general government, but again, the requirement to do this varies by country. Some require the legislature to be explicit when it does this, others hold that extinguishment can be inferred from the government's treatment of the land. In Canada, the Crown cannot extinguish aboriginal title without the explicit prior informed consent of the proper aboriginal title holders. New Zealand formerly required consent, but today requires only a justification, akin to a public purpose requirement.

Jurisdictions differ on whether the state is required to pay compensation upon extinguishing aboriginal title. Theories for the payment of compensation include the right to property, as protected by constitutional or common law, and the breach of a fiduciary duty.

Percentage of land

[edit]- Native title in Australia - 8,099,264 square kilometres (3,127,143 sq mi)[13]: 2 (50.2% of the area of the country's land and waters)[13]: 4 as of 2023[update]

- Indian reserves in Canada - 28,000 square kilometres (11,000 sq mi) (0.2804% of the country's land area)[citation needed]

- Native Community Lands in Bolivia - 168,000 square kilometres (65,000 sq mi) (15% of the country's land area)[citation needed]

- Indigenous territories in Brazil - 1,105,258 square kilometres (426,742 sq mi) (13% of the country's land area)[citation needed]

- Indigenous territories in Colombia - 1,141,748 square kilometres (440,831 sq mi) (31.5% of the country's land area)[citation needed]

- Indian reservations in the United States - 227,000 square kilometres (88,000 sq mi) (2.308% of the country's land area)[citation needed]

History by jurisdiction

[edit]Australia

[edit]Australia did not experience native title litigation until the 1970s, when Indigenous Australians (both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people) became more politically active, after being included in the Australian citizenry as a result of the 1967 referendum.[n 2] In 1971, Blackburn J of the Supreme Court of the Northern Territory rejected the concept in Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd (the "Gove land rights case").[14] The Aboriginal Land Rights Commission was established in 1973 in the wake of Milirrpum. Paul Coe, in Coe v Commonwealth (1979), attempted (unsuccessfully) to bring a class action on behalf of all Aborigines claiming all of Australia.[15] The Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1976,[16] established a statutory procedure that returned approximately 40% of the Northern Territory to Aboriginal ownership; the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Land Rights Act 1981,[17] had a similar effect in South Australia.

The High Court of Australia, after paving the way in Mabo No 1 by striking down a State statute under the Racial Discrimination Act 1975,[18] overruled Milirrpum in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992).[19] Mabo No 2, rejecting terra nullius, held that native title exists (6–1) and is extinguishable by the sovereign (7–0), without compensation (4–3). In the wake of the decision, the Australian Parliament passed the Native Title Act 1993 (NTA),[20] codifying the doctrine and establishing the National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT). Western Australia v Commonwealth upheld the NTA and struck down a conflicting Western Australia statute.[21]

In 1996, the High Court held that pastoral leases, which cover nearly half of Australia, do not extinguish native title in Wik Peoples v Queensland.[22] In response, Parliament passed the Native Title Amendment Act 1998 (the "Ten Point Plan"), extinguishing a variety of Aboriginal land rights and giving state governments the ability to follow suit.

Western Australia v Ward (2002) held that native title is a bundle of rights, which may be extinguished one by one, for example, by a mining lease.[23] Yorta Yorta v Victoria (2002), an appeal from the first native title claim to go to trial since the Native Title Act, adopted strict requirements of continuity of traditional laws and customs for native title claims to succeed.[24]

Belize

[edit]In A-G for British Honduras v Bristowe (1880), the Privy Council held that the property rights of British subjects who had been living in Belize under Spanish rule with limited property rights, were enforceable against the Crown, and had been upgraded to fee simple during the gap between Spanish and British sovereignty.[25] This decision did not involve indigenous peoples, but was an important example of the key doctrines that underlie aboriginal title.[26]

In 1996, the Toledo Maya Cultural Council (TMCC) and the Toledo Alcaldes Association (TAA) filed a claim against the government of Belize in the Belize Supreme Court, but the Court failed to act on the claim.[27] The Maya peoples of the Toledo District filed a complaint with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), which sided with the Maya in 2004 and stated that the failure of the government of Belize to demarcate and title the Maya cultural lands was a violation of the right to property in Article XXIII of the American Declaration.[28] In 2007, Chief Justice Abdulai Conteh ruled in favor of the Maya communities of Conejo and Santa Cruz, citing the IACHR judgement and key precedents from other common law jurisdictions.[27] The government entered into negotiations with the Maya communities, but ultimately refused to enforce the judgement.

In 2008, The TMCC and TAA, and many individual alcaldes, filed a representative action on behalf of all the Maya communities of the Toledo District, and on 28 June 2010, CJ Conteh ruled in favor of the claimants, declaring that Maya customary land tenure exists in all the Maya villages of the Toledo District, and gives rise to collective and individual property rights under sections 3(d) and 17 of the Belize Constitution.[29]

Botswana

[edit]A Botswana High Court recognized aboriginal title in Sesana and Others v Attorney General (2006), a case brought by named plaintiff Roy Sesana, which held that the San have the right to reside in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR), which was violated by their 2001 eviction.[30] The decision quoted Mabo and other international case law, and based the right on the San's occupation of their traditional lands from time immemorial. The court described the right as a "right to use and occupy the lands" rather than a right of ownership. The government has interpreted the ruling very narrowly and has allowed only a small number of San to re-enter the CKGR.

Canada

[edit]Aboriginal title has been recognized in Common Law in Canada since the Privy Council, in St. Catharines Milling v. The Queen (1888), characterized it as a personal usufruct at the pleasure of the Queen.[31] This case did not involve indigenous parties, but rather was a lumber dispute between the provincial government of Ontario and the federal government of Canada. St. Catharines was decided in the wake of the Indian Act (1876), which laid out an assimilationist policy towards the Aboriginal peoples in Canada (First Nations, Inuit, and Métis). It allowed provinces to abrogate treaties (until 1951), and, from 1927, made it a federal crime to prosecute First Nation claims in court, raise money, or organize to pursue such claims.[32]

St. Catharines was more or less the prevailing law until Calder v. British Columbia (Attorney General) (1973). All seven of the judges in Calder agreed that the claimed Aboriginal title existed, and did not solely depend upon the Royal Proclamation of 1763.[33] Six of the judges split 3–3 on the question of whether Aboriginal title had been extinguished. The Nisga'a did not prevail because the seventh justice, Pigeon J, found that the Court did not have jurisdiction to make a declaration in favour of the Nisga'a in the absence of a fiat of the Lieutenant-Governor of B.C. permitting suit against the provincial government.[33]

Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867 ("British North America Act 1867") gives the federal government exclusive jurisdiction over First Nations, and thus the exclusive ability to extinguish Aboriginal title. Section Thirty-five of the Constitution Act, 1982 explicitly recognized and preserved aboriginal rights. R. v. Guerin (1982), the first Supreme Court of Canada decision handed down after the Constitution Act 1982, declared that Aboriginal title was sui generis and that the federal government has a fiduciary duty to preserve it.[34] R. v. Simon (1985) overruled R. v. Syliboy (1929)[35] which had held that Aboriginal peoples had no capacity to enter into treaties, and thus that the Numbered Treaties were void.[36] A variety of non-land rights cases, anchored on the Constitution Act 1982, have also been influential.[37][38][39][40][41][42]

Delgamuukw v. British Columbia (1997) laid down the essentials of the current test to prove Aboriginal title: "in order to make out a claim for [A]boriginal title, the [A]boriginal group asserting title must satisfy the following criteria: (i) the land must have been occupied prior to sovereignty, (ii) if present occupation is relied on as proof of occupation pre-sovereignty, there must be a continuity between present and pre-sovereignty occupation, and (iii) at sovereignty, that occupation must have been exclusive."[43][44][45][46][47][48]

Subsequent decisions have drawn on the fiduciary duty to limit the ways in which the Crown can extinguish Aboriginal title,[49] and to require prior consultation where the government has knowledge of a credible, but yet unproven, claim to Aboriginal title.[50][51]

In 2014 the Supreme Court ruled unanimously for the plaintiff in Tsilhqot'in Nation v. British Columbia. Rejecting the government's claim that Aboriginal title applied only to villages and fishing sites, it instead agreed with the First Nation that Aboriginal title extends to the entire traditional territory of an indigenous group, even if that group was semi-nomadic and did not create settlements on that territory. It also stated that governments must have consent from First Nations which hold Aboriginal title in order to approve developments on that land, and governments can override the First Nation's wishes only in exceptional circumstances. The court reaffirmed, however, that areas under Aboriginal title are not outside the jurisdiction of the provinces, and provincial law still applies.[52][53]

Mainland China

[edit]Japan

[edit]In 2008, Japan gave partial recognition to the Ainu people.[54] However, land rights were not given for another eleven years.

In 2019, Japan fully recognised the Ainu people as the indigenous people of Japan and gave them some land rights if requested.[55][56]

Malaysia

[edit]Malaysia recognised various statutory rights related to native customary laws (adat) before its courts acknowledged the independent existence of common law aboriginal title. Native Customary Rights (NCR) and Native Customary Land (NCL) are provided for under section 4(2) of the National Land Code 1965, the Sarawak Land Code 1957, the respective provisions of the National Land Code (Penang and Malacca Titles) Act 1963, and the Customary Tenure Enactment (FMS).[57] Rajah's Order IX of 1875 recognized aboriginal title by providing for its extinguishment where cleared land was abandoned. Rajah's Order VIII of 1920 ("Land Order 1920") divided "State Lands" into four categories, one of them being "native holdings", and provided for the registration of customary holdings. The Aboriginal People's Act 1954 creates aboriginal areas and reserves, also providing for state acquisition of land without compensation. Article 160 of the Federal Constitution declares that custom has the force of law.

Malaysian court decisions from the 1950s on have held that customary lands were inalienable.[58][59][60][61][62] In the 1970s, aboriginal rights were declared to be property rights, as protected by the Federal Constitution.[63] Decisions in the 1970s and 1980s blocked state-sanctioned logging on customary land.[64][65]

In 1997, Mokhtar Sidin JCA of the Jahore High Court became the first Malaysian judge to acknowledge common law aboriginal title in Adong bin Kuwau v. Kerajaan Negeri Johor.[66] The High Court cited the Federal Constitution and the Aboriginal Peoples Act, as well as decisions from the Privy Council, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. That case was the first time where Orang Asli directly and expressly challenged a state taking of their land. The opinion held that: "the aborigines' common law rights include, inter alia, the right to live on their land as their forefathers had lived." The case was upheld on appeal, but the Federal Court did not write an opinion.[67]

Later High Court and Court of Appeal decisions built upon the foundation of Adong bin Kuwau.[68][69][70][71][72][73][74] However, the ability for indigenous peoples to bring such suits was seriously limited by a 2005 ruling that claims must be brought under O. 53 RHC, rather than the representative action provision.[75]

In 2007, the Federal Court of Malaysia wrote an opinion endorsing common law aboriginal title for the first time in Superintendent of Lands v. Madeli bin Salleh.[76] The Federal Court endorsed Mabo and Calder, stating that "the proposition of law as enunciated in these two cases reflected the common law position with regard to native titles throughout the Commonwealth."[76]: para 19 The High Court of Kuching held in 2010, for the first time, that NCL may be transferred for consideration between members of the same community, as long as such transfers are not contrary to customary law.[77]

New Zealand

[edit]

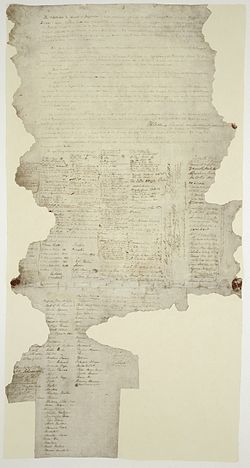

New Zealand was the second jurisdiction in the world to recognize aboriginal title, but a slew of extinguishing legislation (beginning with the New Zealand land confiscations) has left the Māori with little to claim except for river beds, lake beds, and the foreshore and seabed. In 1847, in a decision that was not appealed to the Privy Council, the Supreme Court of the colony of New Zealand recognized aboriginal title in R v Symonds.[78] The decision was based on common law and the Treaty of Waitangi (1840). Chapman J went farther than any judge—before or since—in declaring that aboriginal title "cannot be extinguished (at least in times of peace) otherwise than by the free consent of the Native occupiers".[78]: 390

The New Zealand Parliament responded with the Native Lands Act 1862, the Native Rights Act 1865 and the Native Lands Act 1865 which established the Native Land Court (today the Māori Land Court) to hear aboriginal title claims, and—if proven—convert them into freehold interests that could be sold to Pākehā (New Zealanders of European descent). That court created the "1840 rule", which converted Māori interests into fee simple if they were sufficiently in existence in 1840, or else disregarded them.[79][80] Symonds remained the guiding principle,[81] until Wi Parata v the Bishop of Wellington (1877).[82] Wi Parata undid Symonds, advocating the doctrine of terra nullius and declaring the Treaty of Waitangi unenforceable.

The Privy Council disagreed in Nireaha Tamaki v Baker,[83] and other rulings,[84][85] but courts in New Zealand continued to hand down decisions materially similar to Wi Parata.[86] The Coal Mines Amendment Act 1903[n 3] and the Native Land Act 1909 declared aboriginal title unenforceable against the Crown. Eventually, the Privy Council acquiesced to the view that the Treaty was non-justiciable.[87]

Land was also lost under other legislation. The Counties Act 1886 s.245 said that tracks, "over any Crown lands or Native lands, and generally used without obstruction as roads, shall, for the purposes of this section, be deemed to be public roads, not exceeding sixty-six feet in width, and under the control of the Council".[88] Opposition to such confiscation was met by force, as at Opuatia in 1894.[89] A series of Acts, beginning a year after the Treaty of Waitangi with the Land Claims Ordinance 1841, allowed the government to take and sell 'Waste Lands'.[90]

Favorable court decisions turned aboriginal title litigation towards the lake beds,[91][92] but the Māori were unsuccessful in claiming the rivers[93] the beaches,[94] and customary fishing rights on the foreshore.[95] The Limitation Act 1950 established a 12-year statute of limitations for aboriginal title claims (6 years for damages), and the Maori Affairs Act 1953 prevented the enforcement of customary tenure against the Crown. The Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 created the Waitangi Tribunal to issue non-binding decisions, concerning alleged breaches of the Treaty, and facilitate settlements.

Te Weehi v Regional Fisheries Office (1986) was the first modern case to recognize an aboriginal title claim in a New Zealand court since Wi Parata, granting non-exclusive customary fishing rights.[96] The Court cited the writings of Dr Paul McHugh and indicated that whilst the Treaty of Waitangi confirmed those property rights, their legal foundation was the common law principle of continuity. The Crown did not appeal Te Weehi which was regarded as the motivation for Crown settlement of the sea fisheries claims (1992). Subsequent cases began meanwhile—and apart from the common law doctrine—to rehabilitate the Treaty of Waitangi, declaring it the "fabric of New Zealand society" and thus relevant even to legislation of general applicability.[97] New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General held that the government owed a duty analogous to a fiduciary duty toward the Māori.[98][99] This cleared the way for a variety of Treaty-based non-land Māori customary rights.[100][101][102] By this time the Waitangi Tribunal in its Muriwhenua Fishing Report (1988) was describing Treaty-based and common law aboriginal title derived rights as complementary and having an 'aura' of their own.

Circa the Te Ture Whenua Māori Act 1993, less than 5% of New Zealand was held as Māori customary land. In 2002, the Privy Council confirmed that the Maori Land Court, which does not have judicial review jurisdiction, was the exclusive forum for territorial aboriginal title claims (i.e. those equivalent to a customary title claim)[103] In 2003, Ngati Apa v Attorney-General overruled In Re the Ninety-Mile Beach and Wi Parata, declaring that Māori could bring claims to the foreshore in Land Court.[104][105] The Court also indicated that customary aboriginal title interests (non-territorial) might also remain around the coastline. The Foreshore and Seabed Act 2004 extinguished those rights before any lower court could hear a claim to either territorial customary title (the Maori Land Court) or non-territorial customary rights (the High Court's inherent common law jurisdiction). That legislation has been condemned by the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. The 2004 Act was repealed with the passage of the Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Act 2011.

Papua New Guinea

[edit]The High Court of Australia, which had appellate jurisdiction before 1975, recognized aboriginal title in Papua New Guinea—decades before it did so in Australia—in Geita Sebea v Territory of Papua (1941),[106] Administration of Papua and New Guinea v Daera Guba (1973) (the "Newtown case"),[107] and other cases.[108][109] The Supreme Court of Papua New Guinea followed suit.[110][111][112][113][114]

Schedule 2 of the Constitution of Papua New Guinea recognizes customary land tenure, and 97% of the land in the country remains unalienated.

Russia

[edit]South Africa

[edit]

In Alexkor v Richtersveld Community (2003), a suit under the Restitution of Land Rights Act 1994,[115] lawyers gathered case law from settler jurisdictions around the world, and judges of the Constitutional Court of South Africa talked frankly about Aboriginal title.[116] The Land Claims Court had dismissed the complaint of the Richtersveld peoples, whose land was seized by a government owned diamond mining operation.[117] The Supreme Court of Appeal disagreed, citing Mabo and Yorta Yorta, but held that the aboriginal title had been extinguished.[118] Whether the precedent will be the start of further land rights claims by indigenous peoples is an open question, given the cut-off date of 1913 in the Restitution Act.[119][120][121]

The case ultimately did not lead to the inclusion of the Aboriginal title in South African doctrine.[116] Legal scholars allege that this is because the application of terms like 'indigenous' and 'Aboriginal' in a South African context would lead to a number of contradictions.[116]

The identity of the indigenous groups in South Africa is not self-evident.[122] The adoption of a strict definition, including only communities descended from San and Khoekhoe people, would entail the exclusion of black African communities, an approach deemed detrimental to the spirit of national unity.[122] The legacy of the Natives Land Act also means that few communities retain relationships with the land of which they held before 1913.[122]

Taiwan

[edit]

Taiwanese indigenous peoples are Austronesian peoples, making up a little over 2% of Taiwan's population; the rest of the population is composed of ethnic Chinese who colonised the island from the 17th century onward.

From 1895 Taiwan was under Japanese rule and indigenous rights to land were extinguished.[123] In 1945, the Republic of China (ROC) took control of Taiwan from the Empire of Japan; a rump Republic of China was established on Taiwan in 1949 after the Communists won the Chinese Civil War. From then, indigenous people's access to traditional lands was limited, as the ROC built cities, railroads, national parks, mines and tourist attractions.[124] In 2005 the Basic Law for Indigenous Peoples was passed.[125][126]

In 2017 the Council of Indigenous Peoples declared 18,000 square kilometres (6,900 sq mi), about half of Taiwan's land area (mostly in the east of the island), to be "traditional territory"; about 90 percent is public land that indigenous people can claim, and to whose development they can consent or not; the rest is privately owned.[127]

Tanzania

[edit]In 1976, the Barabaig people challenged their eviction from the Hanang District of the Manyara Region, due to the government's decision to grow wheat in the region, funded by the Canadian Food Aid Programme.[128][129] The wheat program would later become the National Agricultural and Food Corporation (NAFCO). NAFCO would lose a different suit to the Mulbadaw Village Council in 1981, which upheld customary land rights.[130] The Court of Appeal of Tanzania overturned the judgement in 1985, without reversing the doctrine of aboriginal title, holding that the specific claimants had not proved that they were native.[131] The Extinction of Customary Land Right Order 1987,[132] which purported to extinguish Barabaig customary rights, was declared null and void that year.[133]

The Court of Appeal delivered a decision in 1994 that sided with the aboriginal title claimant on nearly all issues, but ultimately ruled against them, holding that the Constitution (Consequential, Transitional and Temporary Provisions) Act, 1984—which rendered the constitutional right to property enforceable in court—was not retroactive.[134] In 1999, the Maasai were awarded monetary compensation and alternative land by the Court of Appeal due to their eviction from the Mkomazi Game Reserve when a foreign investor started a rhino farm.[135] The government has yet to comply with the ruling.

United States

[edit]The United States, under the tenure of Chief Justice John Marshall, became the first jurisdiction in the world to judicially acknowledge (in dicta) the existence of aboriginal title in series of key decisions. Marshall envisioned a usufruct, whose content was limited only by "their own discretion", inalienable except to the federal government, and extinguishable only by the federal government.[136] Early state court decisions also presumed the existence of some form of aboriginal title.[137][138]

Later cases established that aboriginal title could be terminated only by the "clear and plain intention" of the federal government, a test that has been adopted by most other jurisdictions.[139] The federal government was found to owe a fiduciary duty to the holders of aboriginal title, but such duty did not become enforceable until the late-20th century.[140][141][142]

Although the property right itself is not created by statute, sovereign immunity barred the enforcement of aboriginal title until the passage of the Indian Claims Commission Act of 1946,[143] which created the Indian Claims Commission (succeeded by the United States Court of Claims in 1978, and later the United States Court of Federal Claims in 1982). These bodies have no authority to title land, only to pay compensation. United States v. Alcea Band of Tillamooks (1946) was the first ever judicial compensation for a taking of Indian lands unrecognized by a specific treaty obligation.[144] Tee-Hit-Ton Indians v. United States (1955) established that the extinguishment of aboriginal title was not a "taking" within the meaning of the Fifth Amendment.[145] On the strength of this precedent, claimants in the Court of Federal Claims have been denied interest—which otherwise would be payable under Fifth Amendment jurisprudence—totalling billions of dollars ($9 billion alone, as estimated by a footnote in Tee-Hit-Ton, in interest for claims then pending based on existing jurisdictional statutes).[146]

Unlike Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, the United States allows aboriginal title to be created post-sovereignty; rather than existing since pre-sovereignty, aboriginal title need only have existed for a "long time" (as little as 30 years) to be compensable.[147]

Jurisdiction rejecting the doctrine

[edit]

There is no possibility for aboriginal title litigation in some Commonwealth jurisdictions; for instance, Barbados and the Pitcairn Islands were uninhabited for hundreds of years prior to colonization, although they had previously been inhabited by the Arawak and Carib, and Polynesian peoples, respectively.[148]

India

[edit]Unlike most jurisdictions, the doctrine that aboriginal title is inalienable never took hold in India. Sales of land from indigenous persons to both British subjects and aliens were widely upheld.[149] The Pratt–Yorke opinion (1757), a joint opinion of England's Attorney-General and Solicitor-General, declared that land purchases by the British East India Company from the Princely states were valid even without a Crown patent authorizing the purchase.

In a 1924 appeal from India, the Privy Council issued an opinion that largely corresponded to the Continuity Doctrine: Vaje Singji Jorava Ssingji v Secretary of State for India.[150] This line of reasoning was adopted by the Supreme Court of India in a line of decisions, originating with the proprietary claims of the former rulers of the Princely states, as well as their heirs and assigns.[151][152][153][154] Adivasi land rights litigation has yielded little result. Most Adivasi live in state-owned forests.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ For modern litigation over the same land, see Mohegan Tribe v. Connecticut, 483 F. Supp. 597 (D. Conn. 1980), aff'd, 638 F.2d 612 (2d Cir. 1980), cert. denied 452 U.S. 968, on remand, 528 F. Supp. 1359 (D. Conn. 1982).

- ^ Several earlier cases tangentially involved issues of native title: Attorney-General v Brown (1847) 1 Legge 312; 2 SCR (NSW) App 30; Cooper v Stuart [1889] UKLawRpAC 7, (1889) 14 App Cas 286 (3 April 1889), Privy Council (on appeal from NSW); Williams v Attorney General (NSW) [1913] HCA 33, (1913) 16 CLR 404, High Court (Australia); Randwick Corporation v Rutledge [1959] HCA 63, (1959) 102 CLR 54, High Court (Australia); Wade v New South Wales Rutile Mining Co Pty Ltd [1969] HCA 28, (1969) 121 CLR 177, High Court (Australia).

- ^ Currently, section 261 of the Coal Mines Act 1979.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d McNeil, 1989, at 161–179.

- ^ The Case of Tanistry (1608) Davis 28 (conquest of Ireland).

- ^ Witrong v. Blany (1674) 3 Keb. 401 (conquest of Wales).

- ^ Calvin's Case (1608) 77 E.R. 377, 397–98 (K.B.):

"All infidels are in law perpetui inimici, perpetual enemies (for the law presumes not that they will be converted, that being remota potentia, a remote possibility) for between them, as with the devils, whose subjects they be, and the Christian, there is perpetual hostility, and can be no peace; . . . And upon this ground there is a diversity between a conquest of a kingdom of a Christian King, and the conquest of a kingdom of an infidel; for if a King come to a Christian kingdom by conquest, . . . he may at his pleasure alter and change the laws of that kingdom: but until he doth make an alteration of those laws the ancient laws of that kingdom remain. But if a Christian King should conquer a kingdom of an infidel, and bring them under his subjection, there ipso facto the laws of the infidel are abrogated, for that they be not only against Christianity, but against the law of God and of nature, contained in the decalogue; and in that case, until certain laws be established amongst them, the King by himself, and such Judges as he shall appoint, shall judge them and their causes according to natural equity." - ^ Campbell v. Hall (1774) Lofft 655.

- ^ Oyekan & Ors v Adele [1957] 2 All ER 785 (Nigeria).

- ^ Mark Walters, "'Mohegan Indians v. Connecticut'(1705–1773) and the Legal Status of Aboriginal Customary Laws and Government in British North America" Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 33 Osgoode Hall L.J. 4 (2007).

- ^ In re Southern Rhodesia [1919] AC 211.

- ^ In re Southern Rhodesia [1919] AC 211, 233–34.

- ^ a b Amodu Tijani v. Southern Nigeria (Secretary), [1921] 2 AC 399.

- ^ In chronological order: Sobhuza II v Miller [1926] AC 518 (Swaziland); Sunmonu v Disu Raphael (Deceased) [1927] AC 881 (Nigeria); Bakare Ajakaiye v Lieutenant Governor of the Southern Provinces [1929] AC 679 (Nigeria); Sakariyawo Oshodi v Moriamo Dakolo (4) [1930] AC 667 (Nigeria); Stool of Abinabina v. Chief Kojo Enyimadu (1953) AC 207 (West African Gold Coast); Nalukuya (Rata Taito) v Director of Lands [1957] AC 325 (Fiji); Adeyinka Oyekan v Musendiku Adele [1957]2 All ER 785 (West Africa).

- ^ Nyali v Attorney General [1956] 1 QB 1 (Lord Denning).

- ^ a b "Native title snapshot 2023" (PDF). Australasian Legal Information Institute. National Native Title Tribunal. 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd (1971) 17 FLR 141 (27 April 1971) Supreme Court (NT, Australia).

- ^ Coe v Commonwealth [1979] HCA 68, High Court (Australia)

- ^ Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth).

- ^ Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Land Rights Act 1981 (SA).

- ^ Mabo v Queensland (No 1) [1988] HCA 69, (1988) 166 CLR 186 (8 December 1988), High Court (Australia).

- ^ Mabo v Queensland (No 2) [1992] HCA 23, (1992) 175 CLR 1 (3 June 1992), High Court (Australia).

- ^ Native Title Act (Cth).

- ^ Western Australia v Commonwealth [1995] HCA 47, (1988) 166 CLR 186 (16 March 1995), High Court (Australia).

- ^ Wik Peoples v The State of Queensland [1996] HCA 40, (1996) 187 CLR 1 (23 December 1996), High Court (Australia).

- ^ Western Australia v Ward [2002] HCA 28, (2002) 213 CLR 1 (8 August 2002), High Court (Australia)

- ^ Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria [2002] HCA 58, (2002) 214 CLR 422 "Judgment Summary" (PDF). High Court (Australia). 12 December 2002.

- ^ Attorney-General for British Honduras v Bristowe [1880] UKPC 46, (1880) 6 AC 143, Privy Council (on appeal from British Honduras).

- ^ McNeil, 1989, at 141–147.

- ^ a b Supreme Court Claims Nos. 171 and 172 of 2007 (Consolidated) re Maya land rights Archived 17 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. 12 October 2004. Report Nº 40/04, Case 12.053, Merits, Maya Indigenous Communities of the Toledo District, Belize Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Supreme Court Claim No. 366 of 2008 – The Maya Leaders Alliance and the Toledo Alcaldes et al v The Attorney General of Belize et al and Francis Johnston et al Archived 16 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Sesana and Others v Attorney General (52/2002) [2006] BWHC 1.

- ^ St. Catharines Milling v. The Queen (1888) 14 App. Cas. 46.

- ^ Johnson, Ralph W. (1991). "Fragile Gains: two centuries of Canadian and United States policy toward Indians". Washington Law Review. 66 (3): 643.

- ^ a b Calder v. British Columbia (Attorney General) (1973) 34 DRL (3d) 145.

- ^ R. v. Guerin [1984] 2 S.C.R. 335 (Wilson J.).

- ^ R. v. Syliboy [1929] 1 D.L.R. 307 (Nova Scotia County Court).

- ^ R. v. Simon [1985] 2 S.C.R. 387.

- ^ R. v. Sparrow [1990] 1 S.C.R. 1075.

- ^ R. v. Adams (1996) 138 DLR (4th) 657.

- ^ R. v. Van der Peet (1996) 137 DLR (4th) 289.

- ^ R. v. Côté [1996] 3 S.C.R. 139.

- ^ R. v. Sappier [2006] 2 S.C.R. 686.

- ^ R. v. Morris [2006] 2 S.C.R. 915.

- ^ Delgamuukw v. British Columbia [1997] 153 D.L.R. (4th).

- ^ Mitchell v. Canada [2001] 1 S.C.R. 911.

"Stripped to essentials, an [A]boriginal claimant must prove a modern practice, tradition or custom that has a reasonable degree of continuity with the practices, traditions or customs that existed prior to contact. The practice, custom or tradition must have been "integral to the distinctive culture" of the [A]boriginal peoples, in the sense that it distinguished or characterized their traditional culture and lay at the core of the peoples' identity. It must be a "defining feature" of the Aboriginal society, such that the culture would be "fundamentally altered" without it. It must be a feature of "central significance" to the peoples' culture, one that "truly made the society what it was" (Van der Peet, supra, at paras. 54–59). This excludes practices, traditions and customs that are only marginal or incidental to the Aboriginal society's cultural identity, and emphasizes practices, traditions and customs that are vital to the life, culture and identity of the aboriginal society in question." (Paragraph 12) - ^ Tsilhqot'in Nation v. British Columbia, 2007 BCSC 1700.

- ^ R. v. Marshall, 2005 SCC 43.

- ^ Bartlett, R.. "The Content and Proof of Native Title: Delgamuukw v Queen in right of British Columbia", Indigenous Law Bulletin 19 (1998).

- ^ Bartlett, R., "The Different Approach to Native Title in Canada," Australian Law Librarian 9(1): 32–41 (2001).

- ^ Osoyoos Indian Band v. Oliver (Town), 2001 SCC 85.

- ^ Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), 2004 SCC 73.

- ^ Mikisew Cree First Nation v. Canada (Minister of Canada Heritage), 2005 SCC 69.

- ^ "Landmark Supreme Court ruling grants land title to B.C. First Nation". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 17 January 2025.

- ^ Fine, Sean (26 June 2014). "Supreme Court expands land-title rights in unanimous ruling". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "Indigenous World 2020: Japan - IWGIA - International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs".

- ^ "Japan: New Ainu Law Becomes Effective". Library of Congress.

- ^ "Japan's 'vanishing' Ainu will finally be recognized as indigenous people". 20 April 2019.

- ^ Cooke, Fadzilah Majid, ed. (2006). Defining Native Customary Rights to Land. ANU Press. doi:10.22459/SCFCB.07.2006. ISBN 9781920942519. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Sumbang Anak Sekam v Engkarong Anak Ajah [1958] SCR 95.

- ^ Sat Anak Akum & Anor v RAndong Anak Charanak Charereng [1958] SCR 104.

- ^ Galau & Ors v Penghuluimang & Ors [1967] 1 MLJ 192.

- ^ Bisi ak Jinggot @ Hilarion Bisi ak Jenggut v Superintendent of Lands and Surveys Kuching Division & Ors [2008] 4 MLJ 415.

- ^ Sapiah binti Mahmud (F) v Superintendent of Lands and Surveys, Samarahan Division & 2 Ors [2009] MLJU 0410.

- ^ Selangor Pilot Association v Government of Malaysia [1975] 2 MLJ 66.

- ^ Keruntum Sdn Bhd v. Minister of Resource Planning [1987].

- ^ Koperasi Kijang Mas v. Kerajaan Negeri Perak [1991] CLJ 486.

- ^ Adong bin Kuwau v. Kerajaan Negeri Johor [1997] 1 MLJ 418.

- ^ Kerajaan Negri Johor & Anor v Adong bin Kuwau & Ors [1998] 2 MLJ 158.

- ^ Nor anak Nyawai & Ors v Borneo Pulp Plantation Sdn Bhd & Ors [2001] 6 MLJ 241.

- ^ Sagong bin Tasi & Ors v Kerajaan Negeri Selangor & Ors [2002] 2 MLJ 591.

- ^ Kerajaan Negeri Selangor & Ors v Sagong Bin Tasi & Ors [2005] 6 MLJ 289.

- ^ Amit bin Salleh & Ors v The Superintendent, Land & Survey Department, Bintulu & Ors [2005] 7 MLJ 10.

- ^ Madeli bin Salleh (Suing as Administrator of the Estate of the Deceased, Salleh bin Kilong) v Superintendent of Lands & Surveys (Miri Division) and Ors [2005] MLJU 240; [2005] 5 MLJ 305.

- ^ Superintendent of Lands & Surveys, Bintulu v Nor Anak Nyawai & Ors [2005] 4 AMR 621; [2006] 1 MLJ 256.

- ^ Hamit bin Matusin & Ors v Penguasa Tanah dan Survei & Anor [2006] 3 MLJ 289.

- ^ Shaharuddin bin Ali & Anor v Superintendent of Lands and Surveys, Kuching Division & Anor [2005] 2 MLJ 555.

- ^ a b Superintendent of Lands & Surveys Miri Division & Anor v Madeli bin Salleh (suing as the administrator of the estate of the deceased, Salleh bin Kilong) [2007] 6 CLJ 509; [2008] 2 MLJ 677.

- ^ Mohamad Rambli bin Kawi v Superintendent of Lands Kuching & Anor [2010] 8 MLJ 441.

- ^ a b R v Symonds "(1847) NZPCC 387". Archived from the original on 1 May 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Oakura (1866) (unreported) (CJ Fenton).

- ^ Kauwaeranga (1870) (unreported).

- ^ Re Lundon and Whitaker Claims Act 1871 (1872) NZPCC 387.

- ^ Wi Parata v the Bishop of Wellington (1877) 3 N.Z. Jur. (N.S.) 72.

- ^ Nireaha Tamaki v Baker [1901] UKPC 18, [1901] AC 561, Privy Council (on appeal from New Zealand).

- ^ Te Teira Te Paea v Te Roera Tareha [1901] UKPC 50, [1902] AC 56, Privy Council (on appeal from New Zealand).

- ^ Wallis v Solicitor-General for New Zealand [1901] UKPC 50, [1903] AC 173, Privy Council (on appeal from New Zealand).

- ^ Hohepa Wi Neera v Wallis (Bishop of Wellington) [1902] NZGazLawRp 175; (1902) 21 NZLR 655, Court of Appeal (New Zealand).

- ^ Hoani Te Heuheu Tukino v Aotea District Maori Land Board [1941] UKPC 6, [1941] AC 308, Privy Council (on appeal from New Zealand).

- ^ "Counties Act 1886". NZLII.

- ^ "The Opuatia Survey Dispute". The New Zealand Herald. 10 March 1894. p. 5. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Some Government Breaches of Te Tiriti o Waitangi" (PDF). Treaty Resource Centre. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ Tamihana Korokai v Solicitor-General (1912) 32 NZLR 321.

- ^ Re Lake Omapere (1929) 11 Bay of Islands MB 253.

- ^ In Re Bed of Wanganui River [1955].

- ^ In Re Ninety-Mile Beach [1963] NZLR 461.

- ^ Keepa v. Inspector of Fisheries; consolidated with Wiki v. Inspector of Fisheries [1965] NZLR 322.

- ^ Te Weehi v Regional Fisheries Office (1986) 1 NZLR 682.

- ^ Huakina Development Trust v Waikato Valley Authority [1987] 2 NZLR 188.

- ^ New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General [1987] NZCA 60, [1987] 1 NZLR 641, Court of Appeal (New Zealand)..

- ^ New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General [2007] NZCA 269, Court of Appeal (New Zealand)..

- ^ Tainui Maori Trust Board v Attorney-General [1989] 2 NZLR 513 (coal).

- ^ Te Runanganui o Te Ika Whenua Inc Society v Attorney-General [1990] 2 NZLR 641 (fishing rights).

- ^ Ngai Tahu Maori Trust Board v Director-General of Conservation [1995] 3 NZLR 553 (whale watching).

- ^ McGuire v Hastings District Council [2000] UKPC 43; [2002] 2 NZLR 577.

- ^ Attorney-General v Ngati Apa [2002] 2 NZLR 661.

- ^ Attorney-General v Ngati Apa [2003] 3 NZLR 643.

- ^ Geita Sebea v Territory of Papua [1941] HCA 37, (1941) 67 CLR 544, High Court (Australia).

- ^ Administration of Papua and New Guinea v Daera Guba [1973] HCA 59, (1973) 130 CLR 353, High Court (Australia).

- ^ Custodian of Expropriated Property v Tedep [1964] HCA 75, (1964) 113 CLR 318, High Court (Australia).

- ^ Teori Tau v The Commonwealth [1969] HCA 62, (19659) 119 CLR 564, High Court (Australia).

- ^ Tolain, Tapalau, Tomaret, Towarunga, and Other Villagers of Latlat Village v Administration of the Territory of Papua and New Guinea; In re Vulcan Land [1965–66] PNGLR 232.

- ^ Administration of the Territory of Papua and New Guinea v Blasius Tirupia and Others (In Re Vunapaladig and Japalik Land) [1971–72] P&NGLR 229.

- ^ Rahonamo v Enai and Another (Re Hitau) (1971) unreported judgment N612 .

- ^ Toare Karakara v The Independent State of Papua New Guinea [1986] PNGLR 186.

- ^ Madaha Resena and Others v The Independent State of Papua New Guinea [1990] PNGLR 22.

- ^ Alexkor Ltd v Richtersveld Community [2003] ZACC 18; 2004 (5) SA 460; 2003 (12) BCLR 1301.

- ^ a b c Cavanagh, Edward (June 2013). "The History of Dispossession at Orania and the Politics of Land Restitution in South Africa". Journal of Southern African Studies. 39 (2): 391–407. doi:10.1080/03057070.2013.795811. S2CID 216091875.

- ^ Richtersveld Community v Alexkor Ltd and Anor, 2001 (3) 1293 (22 March 2001).

- ^ Richtersveld Community & Ors v Alexkor Limited & Anor (unreported, 24 March 2003).

- ^ Dorsett, S., "Making Amends for Past Injustice: Restitution of Land Rights in South Africa," 4(23) Indigenous Law Bulletin 4(23), pp. 9–11 (1999).

- ^ Mostert, H. and Fitzpatrick, P., Law Against Law: Indigenous Rights and the Richtersveld Decision (2004).

- ^ Patterson, S., "The Foundations of Aboriginal Title in South Africa? The Richtersveld Community v Alexkor Ltd Decisions," Indigenous Law Bulletin 18 (2004).

- ^ a b c Lehmann, Karin (7 April 2017). "Aboriginal Title, Indigenous Rights and the Right to Culture". South African Journal on Human Rights. 20 (1): 86–118. doi:10.1080/19962126.2004.11864810. S2CID 140759377.

- ^ "The First Nations of Taiwan: A Special Report on Taiwan's indigenous peoples". www.culturalsurvival.org. 5 May 2010.

- ^ Aspinwall, Nick (13 February 2019). "Taiwan's indigenous are still seeking justice on the democratic side of the Taiwan Strait". SupChina.

- ^ "Taiwan's first settlers camp out in city for land rights". Reuters. 11 June 2018 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ "Taiwan - IWGIA - International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs". www.iwgia.org.

- ^ "Taiwan's indigenous people take land rights fight to the capital". South China Morning Post. 11 June 2018.

- ^ R. v. Bukunda Kilanga and Others, High Court Sessional Case No. 168 of 1976 (Unreported).

- ^ Noya Gomusha and Others v. R.[1980] TLR 19.

- ^ Mulbadaw Village Council and 67 Others v. National Agricultural and Food Corporation, High Court of Tanzania at Arusha, Civil Case No. 10 of 1981 (Unreported).

- ^ National Agricultural and Food Corporation v. Mulbadaw Village Council and Others [1985] TLR 88.

- ^ Government Notice No. 88 of 13 February 1987.

- ^ Tito Saturo and 7 Others v. Matiya Seneya and Others, High Court of Tanzania at Arusha, Civil Appeal No. 27 of 1985 (Unreported) (Chua, J.).

- ^ Attorney-General v. Lohay Akonaay and Another [1994] TZCA 1; [1995] 2 LRC 399 (Court of Appeal of Tanzania, Civil Appeal No. 31 of 1994) (Nyalali, C.J.).

- ^ Lekengere Faru Parutu Kamunyu and 52 Others v. Minister for Tourism, Natural Resources and Environment and 3 Others, Civil Appeal No 53 of 1998, unreported, (1999) 2 CHRLD 416 (Court of Appeal of Tanzania at Arusha) (Nyalali, C.J.).

- ^ Johnson v. McIntosh, 21 U.S. 543, 573 (1823).

- ^ Marshall v. Clark, 1 Ky. 77 (1791).

- ^ Goodell v. Jackson, 20 Johns. 693 (N.Y. 1823).

- ^ United States v. Santa Fe Pac. R. Co., 314 U.S. 339 (1942).

- ^ Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 553 (1903).

- ^ Seminole Nation v. United States, 316 U.S. 286 (1942).

- ^ United States v Sioux Nation, 448 U.S. 371 (1980).

- ^ 25 U.S.C. § 70, et seq 28 U.S.C. § 1505.

- ^ United States v. Alcea Band of Tillamooks, 329 U.S. 40 (1946).

- ^ Tee-Hit-Ton Indians v. United States, 348 U.S. 272 (1955).

- ^ Fort Berthold Reservation v. United States, 390 F.2d 686, 690 (Ct. Cl. 1968).

- ^ Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas v. United States, 28 Fed Cl 95 (1993); order modified by 2000 WL 1013532 (unreported).

- ^ McNeil, 1989, pp. 136–141, 147–157.

- ^ Freeman v. Fairie (1828) 1 Moo. IA 305.

- ^ Vaje Singji Jorava Ssingji v Secretary of State for India (1924) L.R. 51 I.A. 357.

- ^ Virendra Singh & Ors v. The State of Uttar Pradesh [1954] INSC 55.

- ^ Vinod Kumar Shantilal Gosalia v. Gangadhar Narsingdas Agarwal & Ors [1981] INSC 150.

- ^ Sardar Govindrao & Ors v. State of Madhya Pradesh & Ors [1982] INSC 52.

- ^ R.C. Poudyal & Anr. v. Union of India & Ors [1993] INSC 77.

Further reading

[edit]- Comparative

- Bartlett, Richard H., and Jill Milroy (eds.). 1999. Native Title Claims in Canada and Australia: Delgamuukw and Miriuwung Gajerrong.

- Richard A. Epstein, Property Rights Claims of Indigenous Populations: The View from the Common Law, 31 U. Toledo L. Rev. 1 (1999).

- Hazelhurst, Kayleen M. (ed.). 1995. Legal Pluralism and the Colonial Legacy.

- Hocking, Barbara Ann. 2005. Unfinished constitutional business?: rethinking indigenous self-determination.

- IWGIA. 1993. "...Never Drink from the Same Cup": Proceedings of the conference on indigenous peoples in Africa.

- IWGIA. 2007. The Indigenous World.

- Liversage, Vincent. 1945. Land Tenure in the Colonies. pp. 2–18, 45—53

- Meek, C.K. 1946. Land Law and Custom in the Colonies.

- McHugh, PG. 2011. Aboriginal Title: The Modern Jurisprudence of Tribal Land Rights (Oxford: OUP, 2011)

- McNeil, Kent. 1989. Common Law Aboriginal Title. Oxford University Press.

- McNeil, Kent. 2001. Emerging Justice? essays on indigenous rights in Canada and Australia.

- Robertson, Lindsay G. 2005. Conquest by Law: How the Discovery of America Dispossessed Indigenous Peoples of Their Lands. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514869-X.

- Slattery, Brian. 1983. Ancestral lands, alien laws: judicial perspectives on aboriginal title.

- Young, Simon. 2008. Trouble with tradition: native title and cultural change. Sydney: Federation Press.

- Blake A. Watson, The Impact of the American Doctrine of Discovery on Native Land Rights in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, 34 Seattle U. L. Rev. 507 (2011).

- Australia

- Bartlett, R. 2004 (2d ed.). Native Title in Australia.

- Brockwell, Sally. 1979. Aborigines and the law: a bibliography.

- Law Reform Commission. 1986. The recognition of Aboriginal customary laws. Report No. 31. Parliamentary Paper No. 136/1986.

- McCorquodale, John. 1987. Aborigines and the law: a digest.

- Reynolds, Henry. M.A. Stephenson & Suri Ratnapala (eds.). 1993. Native Title and Pastoral Leases, in Mabo: A Judicial Revolution—The Aboriginal Land Rights Decision and Its Impact on Australian Law.

- Strelein, L. 2009 (2d ed.). Compromised Jurisprudence: Native Title Cases Since Mabo. Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra.

- Bangladesh

- IWGIA. 2000. Land Rights of the Indigenous Peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh.

- Belize

- Grandi, Liza. 2006. Unsettling: land dispossession and the Guatemalan and Belizean frontier colonization process.

- Canada

- Borrows, John. 2002. Recovering Canada: the resurgence of Indigenous law.

- Clark, Bruce A. 1990. Native Liberty, Crown Sovereignty.

- Foster, Hamar, Heather Raven & Jeremy Webber. 2007. Let Right Be Done: Aboriginal title, the Calder case, and the future of indigenous rights.

- Ghana

- Ollennu, N.A. 1962. Customary Land Law in Ghana.

- Guyana

- Bennett, Gordon & Audrey Colson. 1978. The damned: the plight of the Akawaio Indians of Guyana.

- Hong Kong

- Nissim, Roger. 2008 (2d ed.). Land administration and practice in Hong Kong.

- Kenya

- Mackenzie, Fiona. 1998. Land, ecology, and resistance in Kenya, 1880–1952.

- Odhiambo, Atieno. 1981. Siasa: politics and nationalism in E.A..

- Malaysia

- Ramy Bulan. "Native Title as a Proprietary Right under the Constitution in Peninsula Malaysia: A Step in the Right Direction?" 9 Asia Pacific Law Review 83 (2001).

- Bulan, Ramy. "Native Title in Malaysia: A 'Complementary' Sui Generis Right Protected by the Federal Constitution", 11(1) Australian Indigenous Law Review 54 (2007).

- Gray, S. "Skeletal Principles in Malaysia's Common Law Cupboard: the Future of Indigenous Native Title in Malaysian Common Law" Lawasia Journal 99 (2002).

- Porter, A.F. 1967. Land administration in Sarawak.

- Namibia

Legal Assistance Center. 2006. "Our land they took": San land rights under threat in Namibia.

- New Zealand

- Boast, Richard, Andrew Erueti, Doug McPhail & Norman F. Smith. 1999. Maori Land Law.

- Brookfield, F.M. 1999. Waitangi & Indigenous Rights.

- Erueti, A. "Translating Maori Customary Title into Common Law Title." New Zealand Law Journal 421–423 (2003).

- Gilling, Bryan D. "By whose Custom? The Operation of the Native Land Court in the Chatham Islands." 23(3) Victoria University of Wellington Law Review (1993).

- Gilling, Bryan D. "Engine of Destruction? An Introduction to the History of the Maori Land Court." Victoria U. Wellington L. Rev. (1994).

- Hill, R. "Politicising the past: Indigenous scholarship and crown—Maori reparations processes in New Zealand." 16 Social and Legal Studies 163 (2007).

- Leane, G. "Fighting them on the Benches: the Struggle for Native Title Recognition in New Zealand." 8(1) Newcastle Law Review 65 (2004).

- Mikaere, Ani and Milroy, Stephanie. "Treaty of Waitangi and Maori Land Law", NZ Law Review 363 (2000).

- McHugh, Paul G. 1983. Maori land laws of New Zealand: two essays.

- McHugh, Paul G. 1984. "Aboriginal title in New Zealand courts", 2 University of Canterbury Law Review 235–265.

- McHugh, Paul G. 1991. The Maori Magna Carta..

- Williams, David V. 1999. "Te Kooti tango whenua": the Native Land Court 1864–1909.

- Papua New Guinea

- Mugambwa, J.T. 2002. Land law and policy in Papua New Guinea.

- Sack, Peter G. 1973. Land Between Two Laws: Early European land acquisitions in New Guinea.

- South Africa

- Claasens, Aninka & Ben Cousins. 2008. Land, power, and custom: Controversies generated by South Africa's Communal Land Rights Act.

- Tanzania

- Japhet, Kirilo. 1967. The Meru Land Case.

- Peter, Chris Maina. 1997. Human Rights in Tanzania: Selected Cases and Materials. pp. 214–269.

- Peter, Chris Maina, and Helen Kijo-Bisimba. 2007. Law and Justice in Tanzania: Quarter a Century of the Court of Appeal.

- Shivji, Issa G. 1990. State Coercion and Freedom in Tanzania. Human & People's Rights Monograph Series No. 8, Institute of Southern African Studies.

- Tenga, Ringo Willy. 1992. Pastoral Land Rights in Tanzania.

- Widner, Jennifer A. 2001. Building the rule of law.

- Zambia

- Mvunga, Mphanza P. 1982. Land Law and Policy in Zambia.

External links

[edit]Aboriginal title

View on GrokipediaConceptual Foundations

Definition and doctrinal origins

Aboriginal title denotes a collective, pre-sovereign interest in land and resources held by indigenous groups, derived from their exclusive and continuous occupation and control of territory prior to the Crown's assertion of sovereignty in common law jurisdictions such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.[2][3] This right is characterized as sui generis, meaning unique and not fully analogous to standard common law property estates like fee simple, as it stems from indigenous customary laws and practices rather than grant or purchase.[1][10] It vests in the group as a whole, permitting uses tied to traditional practices while potentially extending to other purposes that do not fundamentally alter the land's character, subject to the Crown's underlying title and regulatory authority.[9][11] The doctrinal origins of aboriginal title lie in British imperial common law principles governing colonial acquisition of territory, which distinguished between sovereignty (radical or underlying title acquired by the Crown through settlement, conquest, or cession) and pre-existing indigenous possessory rights that survived such acquisition unless explicitly extinguished.[12][3] Early precedents, such as the 1763 Royal Proclamation in British North America, implicitly acknowledged native land rights by prohibiting private purchases and requiring Crown-mediated treaties, reflecting a pragmatic recognition of indigenous occupation to maintain peace and facilitate governance rather than a theoretical endorsement of equality.[2] This framework drew from feudal notions of tenure, where the sovereign held paramount title but respected customary usages of subjects or allies, adapted to colonial contexts without invoking the discredited terra nullius doctrine that treated lands as unoccupied.[12] In practice, however, enforcement was inconsistent, often subordinated to settler interests, with courts in the 19th century viewing native title as a mere personal or usufructuary right terminable at the Crown's pleasure, as articulated in Canada's St. Catherine's Milling and Lumber Co. v. The Queen (1888).[2] Modern doctrinal crystallization occurred in the 20th century through judicial reinterpretation. In Canada, the Supreme Court's decision in Calder v. British Columbia (Attorney General) on January 31, 1973, marked a pivotal shift, with a 4-3 majority affirming that aboriginal title constituted a legal right enforceable against the Crown, rooted in historical occupation rather than statute or treaty alone, though differing rationales (common law versus royal prerogative) highlighted ongoing tensions.[2][13] This laid the groundwork for constitutional entrenchment under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, emphasizing the sui generis nature tied to pre-contact realities.[10] Similarly, in Australia, the High Court's rejection of terra nullius in Mabo v. Queensland (No. 2) on June 3, 1992, established native title as a burden on the Crown's radical title, originating from traditional laws and customs evidencing connection to land at sovereignty.[14] These developments reflect a causal evolution from empirical acknowledgment of indigenous presence to formalized rights, countering prior assumptions of legal vacuum while preserving Crown sovereignty as the limiting principle.[3][15]Relation to common law property and sovereignty

Aboriginal title constitutes a sui generis interest in land under common law, distinct from conventional property estates such as fee simple absolute, which derive from Crown grants and permit broad alienability. Instead, it originates from an indigenous group's pre-sovereignty occupation, continuity, and adherence to traditional laws and customs, conferring collective rights to exclusive use, occupation, and decision-making over the land's resources.[16] This interest burdens the Crown's underlying radical title, acquired upon assertion of sovereignty, without amounting to full beneficial ownership in the common law sense.[17] Key differences include its inalienability to third parties—limited to surrender to the Crown—and its communal character, which ties rights to cultural continuity rather than individual transferability.[16] [17] The proprietary aspects of aboriginal title provide protections akin to property, such as heritability and compensation for expropriation, but impose inherent limitations: uses must align with the land's cultural and ecological significance, prohibiting actions that would destroy its value for future generations.[16] In Delgamuukw v. British Columbia (1997), the Supreme Court of Canada affirmed that title encompasses "the right to the land itself," enabling economic benefits and control over development, yet subject to justification tests for government infringements under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.[16] Similarly, Tsilhqot'in Nation v. British Columbia (2014) granted title holders ownership-like rights to determine land use, including exclusion of others, but distinguished this from unrestricted common law property by emphasizing its rootedness in pre-contact practices.[18] Aboriginal title operates within the framework of Crown sovereignty, which the common law presumes upon colonial acquisition without automatically extinguishing pre-existing indigenous rights absent clear legislative or executive intent.[17] Courts reject claims that title implies indigenous sovereignty or paramount jurisdiction, viewing it instead as a domestic legal interest subordinate to the state's legislative authority, though the Crown's fiduciary obligations require consultation and accommodation.[16] In Mabo v. Queensland (No. 2) (1992), the High Court of Australia recognized native title as a "personal right" surviving sovereignty, not conferring parallel governance but acknowledging customary burdens on radical title until validly overridden.[17] This doctrine balances historical occupation with the realities of settled governance, prioritizing empirical continuity over abstract sovereignty assertions.[16]Historical Development

Pre-colonial and early colonial precedents

Prior to European colonization, indigenous peoples across territories now comprising Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States maintained land tenure systems rooted in continuous occupation from time immemorial, governed by customary laws that regulated use, inheritance, and exclusion rights within kinship-based or communal frameworks.[19] These systems emphasized practical dominion over land through activities such as hunting, fishing, agriculture, and spiritual practices, with boundaries often enforced via warfare or diplomacy rather than formalized deeds; archaeological and ethnohistorical evidence, including dated artifacts and oral traditions, confirms occupations spanning millennia in regions like the Americas and Australasia.[12] Diversity existed among groups—for instance, nomadic hunter-gatherer patterns in Australian Aboriginal societies contrasted with semi-sedentary tribal territories in North American indigenous nations—but common elements included collective responsibility and spiritual connections to land, unsupported by European-style fee simple ownership.[20] Early colonial encounters in British territories initially pragmatically acknowledged these pre-existing tenures to mitigate conflict, though full legal doctrines emerged later. In North America, the Royal Proclamation of 1763, issued by King George III on October 7, 1763, following Pontiac's War, explicitly reserved lands west of the Appalachian Mountains for indigenous use and prohibited private land purchases or grants without Crown-mediated extinguishment, thereby constituting the first formal imperial recognition of aboriginal possessory rights as burdens on the Crown's radical title.[21] This policy, aimed at stabilizing frontier relations after the Seven Years' War, reflected an understanding that indigenous occupation predated settlement and required consensual cession, influencing subsequent treaties like those from 1764 onward in British Canada.[22] In the Thirteen Colonies, colonial statutes dating to the 17th and 18th centuries, such as Virginia's 1649 law and Pennsylvania's 1682 frame, codified prohibitions on private acquisitions from Native Americans without governmental approval, presupposing native title that could only be alienated through official channels.[23] In Australia, early governors received instructions from the Colonial Office, such as those to Arthur Phillip in 1787, to conciliate with Aboriginal inhabitants and avoid encroaching on their territories, implying an initial deference to native usage despite the later terra nullius doctrine; however, systematic land grants from 1788 onward largely disregarded these without formal cession, leading to conflicts like the Pemulwuy resistance from 1790.[24] In New Zealand, pre-Treaty interactions from James Cook's 1769 voyages documented Maori tribal rohe (territories) defended through hapu (sub-tribal) warfare, with early traders respecting these boundaries to secure resources, foreshadowing the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi's cession framework.[25] These precedents, driven by imperial expediency rather than egalitarian principle, established that Crown sovereignty overlaid but did not automatically extinguish indigenous rights, setting the stage for 19th-century judicial elaboration.[26]British imperial evolution and key cases

The British imperial approach to indigenous land rights evolved from the 18th century onward, distinguishing between colonies acquired by conquest or cession—where pre-existing native titles were generally recognized subject to the Crown's sovereignty—and those deemed "settled" or terra nullius, where such titles were often denied on the basis of perceived lack of civilized institutions. This framework drew from international law principles, including the doctrine of discovery, which granted the discovering sovereign ultimate title while allowing natives usufructory rights unless explicitly extinguished. In practice, policy prioritized Crown control over land alienation to prevent conflicts and ensure orderly settlement, as evidenced by prohibitions on private purchases from indigenous groups across multiple colonies.[3][19] A pivotal development occurred with the Royal Proclamation of 1763, issued by King George III on October 7, 1763, following the Seven Years' War and the acquisition of French territories in North America. The Proclamation reserved lands west of the Appalachian Mountains for indigenous use, declared all prior private grants void, and mandated that any extinguishment of native titles required Crown purchase through treaty or consent, effectively affirming aboriginal possessory rights as a burden on the underlying Crown sovereignty. This measure aimed to stabilize frontier relations amid Pontiac's Rebellion and established a template for subsequent British North American treaties, such as those between 1763 and 1860, which systematically acquired over 35 million acres via negotiation with First Nations. The Proclamation's principles influenced colonial statutes in the Thirteen Colonies, where laws from the 17th and 18th centuries, such as Virginia's 1691 act and Massachusetts' 1700 prohibition, barred individual land deals with natives to centralize authority under the Crown.[27][21][28] In New Zealand, imperial policy shifted toward formal recognition via the Treaty of Waitangi, signed on February 6, 1840, between the Crown and Maori chiefs, which ceded sovereignty but guaranteed Maori possession of lands, forests, and fisheries, with the Crown holding preemptive purchase rights. This treaty-based approach contrasted with Australia's classification as a settled colony upon Captain Cook's 1770 voyage and Governor Phillip's 1788 establishment, where no treaties were pursued and lands were treated as waste and unoccupied, enabling waste lands acts from the 1840s onward to facilitate settler grants without native consent. Key judicial interpretations during the imperial era reinforced these variances; in R. v. Symonds (1847), the New Zealand Supreme Court held that native title must be "ascertained and respected" by the Crown before grants to settlers, affirming pre-existing Maori rights under common law. Similarly, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in St. Catherine's Milling and Lumber Co. v. The Queen (1888) characterized aboriginal title in Canada as a "personal and usufructuary right" dependent on the Crown's goodwill, yet personal to the tribe and unalienable except to the sovereign, resolving a dispute over timber rights on surrendered lands by prioritizing provincial ownership subject to the unextinguished Indian interest. These decisions underscored the Crown's fiduciary-like duty while limiting title's scope to use and occupation, not fee simple ownership.[29][9][30]Core Legal Principles

Criteria for recognition of title

In common law jurisdictions, recognition of aboriginal title hinges on demonstrating that indigenous groups occupied specific territories at the time of Crown sovereignty assertion, maintained continuity of connection to those lands, and exercised sufficient control to assert possessory interests akin to ownership. This doctrine, rooted in the inherent pre-existing rights of indigenous peoples, requires evidentiary proof rather than mere assertion, often drawing on historical records, archaeological evidence, and oral traditions where corroborated. The burden lies on claimants to establish these elements without presumption of title, as sovereignty vests radical title in the Crown subject to underlying indigenous interests unless extinguished.[3] The Canadian Supreme Court in Delgamuukw v. British Columbia (1997) defined the test as requiring occupation prior to Crown sovereignty (e.g., before 1846 in British Columbia), continuity of occupation—allowing for interruptions explained by traditional practices rather than abandonment—and exclusivity, meaning the group effectively controlled the land and could exclude others at sovereignty. Present-day occupation suffices if traced back without reliance on Crown grants, with evidence including site-specific indicators of use like villages, fisheries, or trade routes; nomadic patterns do not preclude title if occupation was regular and intensive enough for exclusive claim. Oral evidence from elders holds probative value equivalent to documentary proof when reliable.[31][32] In Australia, the High Court in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) shifted from terra nullius by recognizing native title where a pre-sovereignty body of traditional laws and customs regulated land rights, with claimants proving substantial, uninterrupted continuity of observance and acknowledgment of those customs, alongside ongoing traditional connection via physical, spiritual, or cultural ties. Unlike fee simple, exclusivity is not uniformly required; title encompasses communal rights to possess, enjoy, and use land for customary purposes, but yields to inconsistent non-indigenous grants like freehold. Claimants must show laws and customs not frozen in time but adapted while rooted in pre-1788 traditions, with evidence from anthropological studies and genealogical records.[33][34] These criteria vary by jurisdiction—e.g., New Zealand emphasizes customary rights under the Treaty of Waitangi (1840) with similar occupation proofs, while U.S. federal common law under Johnson v. M'Intosh (1823) limits recognition to unextinguished discovery-era possession without requiring exclusivity for reserved tribal lands—but converge on rejecting radical title denial to indigenous groups absent clear extinguishment. Courts assess sufficiency of occupation contextually, discounting vague or uncorroborated claims, and prioritize empirical evidence over policy-driven interpretations.[35][2]Scope and incidents of aboriginal title

Aboriginal title confers a collective, sui generis interest in land arising from an indigenous group's pre-sovereignty occupation and traditional connection to specific territories, distinct from both fee simple ownership and mere usufructuary rights.[16] In jurisdictions recognizing it under common law, such as Canada, the scope extends to lands where the group demonstrates sufficient, continuous, and exclusive occupation at the time of Crown assertion of sovereignty, encompassing not only surface rights but also a right to the land itself as a burden on the Crown's underlying (radical) title.[16] This territorial scope was affirmed in Canada's Delgamuukw v. British Columbia (1997), where the Supreme Court held that title protects against non-consensual alienation or use by third parties, while in Australia, Mabo v. Queensland (No. 2) (1992) defined native title's scope as varying bundles of rights and interests in relation to land or waters under traditional laws and customs, potentially non-exclusive where historical evidence shows shared or overlapping occupation.[16][36] The core incidents of aboriginal title include the rights to exclusive possession, occupation, use, management, and control of the titled lands, enabling traditional practices, resource harvesting, and decision-making over land use, subject to the indigenous group's fiduciary obligations to preserve the land for present and future generations.[16] In Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia (2014), Canada's Supreme Court clarified that these incidents empower title holders to determine the uses to which the land is put, including commercial or economic development activities, provided they align with the group's distinctive cultural and spiritual attachment and do not destroy the land's inherent value.[4] Unlike alienable private property, title is inalienable to non-indigenous third parties and cannot be fragmented or devised individually, reinforcing its communal character rooted in pre-contact systems of governance.[16] However, the Crown retains ultimate authority to regulate for broader public interests, such as environmental protection or infrastructure, though infringements on titled lands require consent or, absent it, a stringent justification test involving a compelling legislative objective and minimal impairment proportionate to the benefit gained.[4] Jurisdictional variations affect the precise contours: Canadian jurisprudence emphasizes territorial exclusivity and veto-like powers over development on proven title lands, as in Tsilhqot’in, where the Court rejected unilateral Crown grants of third-party interests without negotiation.[4] In contrast, Australian native title under Mabo often manifests as non-possessory rights (e.g., to fish or hunt) co-existing with pastoral leases or mining tenures, with scope limited by historical extinguishment through inconsistent grants, requiring evidence of unbroken traditional connection post-1788.[36] Subsurface resources, such as minerals, typically remain under Crown control unless traditional laws equate them to surface rights, though title holders may claim equitable participation in benefits from exploitation.[16] These incidents underscore aboriginal title's role as a pre-existing legal interest reconciled with Crown sovereignty, but empirical assessments of title claims reveal challenges in proving continuity amid colonial disruptions, with successful declarations covering limited areas relative to asserted territories.[4]Extinguishment and limitations