Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Jolo, Sulu

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2019) |

Jolo, officially the Municipality of Jolo ([hoˈlo]; Tausug: Kawman sin Tiyanggi; Tagalog: Bayan ng Jolo; Chavacano: Municipalidad de Jolo), is a municipality and capital of the province of Sulu, Philippines. According to the 2024 census, it has a population of 152,067 people.[6]

Key Information

Etymology

[edit]According to Dr. Najeeb M. Saleeby (1908) and in old maps such as the Velarde map, "Joló" was the historical Spanish spelling of the word "Sulu" that now refers to the province and the whole Sulu Archipelago, which the early Spaniards historically spelt as "Xoló", with the initial letter most likely formerly pronounced with the Early Modern Spanish [ʃ] sound, with [ʃoˈlo] the Spanish pronunciation of Sulu, but later evolved into the Modern Spanish [x], leading to its modern pronunciation [xoˈlo]. In many dialects, the initial sound is glottal, yielding [hoˈlo]. The Spanish version Joló is still used to pertain Sulu (both province, archipelago, and ancient sultanate) in Spanish writings. Meanwhile, the word "Sulu" itself comes from Tausug: Sulug, an older form of Tausug: Sūg, lit. 'sea current'.[7]

History

[edit]Pre-Colonial period

[edit]In the 14th century, Arab traders landed on the island to introduce and convert its inhabitants to Islam. The native inhabitants on the island are the Tausūg people. The Tausugs are part of the larger Moro group which dominates the Sulu Archipelago. The Moro had an independent state known as the Sultanate of Sulu, which was politically and economically centered on Jolo, the residence for Sulu Sultanates. The Seat of the Royal Sultanate of Sulu was in Astana Putih, which is Tausug for ‘White Palace’ in Umbul Duwa in the municipality of Indanan on Jolo Island, later on, the capital was moved in Maimbung during the 1800s.[8]

Spanish Colonial Period

[edit]The Spanish failed to conquer and convert the Muslim areas in Mindanao. After colonising the islands in the north, they failed to take over the well-organized sultanates in the south.

Trading center

[edit]The Sulu economy relied on the network of nearby trading partners. The Sultanate benefited from importing rice from northern Philippines, as the Sulu region had a chronic rice shortage. The Sultanate was unable to bring agriculture to its full potential because the area was prone to erratic rainfall and drought.

Chinese immigration

[edit]Since the 15th century, the Sulu Sultanate traded local produce with neighbors and with countries as far as China by sea. Most of the import and export trade was done with Singapore which was estimated to be worth half a million dollars annually. In 1870, the Tausug lost much of their redistributive trade to the Chinese because of the Spanish cruising system and Chinese immigration from Singapore. Mostly originating from the Fujian province, most of the Chinese in Jolo worked as craftsmen, skilled and unskilled laborers and domestic servants for wealthy Tausugs and Chinese. Singapore served as a training ground from which they learned the Malay language and became experienced in dealing with Southeast Asians. It was these Chinese who eventually dominated trade in Jolo and benefited greatly from Jolo's status as an entrepot, and exercised profound influence over the Sulu Sultanate. However, the Sultanate was not keen on the Chinese monopoly. By 1875, Sultan Jamal ul-Azam wanted an English merchant to establish himself in order to break the monopoly at Jolo.

Chinese who lived in Sulu ran guns across a Spanish blockade to supply the Moro Datus and Sultanates with weapons to fight the Spanish, who were engaging in a campaign to subjugate the Moro sultanates on Mindanao. A trade involving the Moros selling slaves and other goods in exchange for guns developed. The Chinese had entered the economy of the sultanate, taking control of nearly the entire Sultanate's economy in Mindanao and dominating the markets. Though the Sultans did not like their economic monopoly, they did business with them. The Chinese set up a trading network between Singapore, Zamboanga, Jolo and Sulu.

The Chinese sold small arms like Enfield and Spencer rifles to the Buayan Datu Uto. They were used to battle the Spanish invasion of Buayan. The Datu paid for the weapons in slaves.[9] The population of Chinese in Mindanao in the 1880s was 1,000. The Chinese ran guns across a Spanish blockade to sell to Mindanao Moros. The purchases of these weapons were paid for by the Moros in slaves in addition to other goods. The main group of people selling guns were the Chinese in Sulu. The Chinese took control of the economy and used steamers to ship goods for exporting and importing. Opium, ivory, textiles, and crockery were among the other goods which the Chinese sold.

The Chinese on Maimbung sent the weapons to the Sulu Sultanate, who used them to battle the Spanish and resist their attacks. A Chinese-Mestizo was one of the Sultan's brothers-in-law, the Sultan was married to his sister. He and the Sultan both owned shares in the ship (named the Far East) which helped smuggled the weapons.[10]

The Spanish launched a surprise offensive under Colonel Juan Arolas in April 1887 by attacking the Sultanate's capital at Maimbung in an effort to crush resistance. Weapons were captured and the property of the Chinese was destroyed and the Chinese were deported to Jolo.[11]

Spanish control

[edit]In 1876, the Spanish attempted to gain control of the Muslims by burning Jolo and were successful.[8] In March 1877, The Sulu Protocol was signed between Spain, England and Germany which recognized Spain's rights over Sulu and eased European tensions in the area. The Spanish built the smallest walled city in the world in Jolo. The Spanish and the Sultan of Sulu signed the Treaty of Peace on July 22, 1878, in which the sultan accepted Spanish sovereignty over Sulu and Tawi-Tawi[12][13] but Sulu and Tawi-tawi remained partially ruled by the Spanish as their sovereignty was limited to military stations and garrisons and pockets of civilian settlements.

Trading decline

[edit]Trade suffered heavily in 1892 when three steamers used for trade were lost in a series of storms on the trade route between Singapore and Jolo. The traders in Singapore lost so heavily as a result that they refused to accept trade unless it was paid for in cash. Along with the fear of increased taxation, many Chinese left to other parts of the Archipelago as Jolo lost its role as the regional entrepot. The Tausug had already abandoned trading when the Chinese arrived. Thus, Jolo never fully gained its previous trading status. However, the Chinese continued to dominate trade throughout the Archipelago and Mindanao.[14]

American Colonial Period

[edit]

In 1899 following the Treaty of Paris of 1898, sovereignty over the Philippines was transferred from Spain to the United States who attempted to forcibly incorporate the Muslim areas into the Philippine state. The American colonizers eventually took over the southern regions with force (see Moro Rebellion). The Sultanate of Sulu was abolished in 1936.

Independence

[edit]As a center of regional commerce, Sulu and Jolo became very prosperous and progressive in the years after the end of World War II and the establishment of the Third Philippine Republic.[15] By 1970, the province ranked 37rd in the Philippines in terms of number of households with piped water, and 38th in terms of households with electricity.[16] As the capital of the province, Jolo even saw international trade with countries like China and Russia.[16] This changed suddenly after the 1974 Siege of Jolo,[15] which destroyed infrastructure and led to capital flight and brain drain.[16] By 1990 Jolo had dropped to 52nd in terms of number of households with piped water and 73rd in terms of households with electricity.[16]

In 1974, Jolo was occupied by members of the Moro National Liberation Front, and put under siege by the Philippine Army in the Battle of Jolo. The town suffered extensive damage, with Filipino forces bombarding it from the air.[citation needed]

Geography

[edit]The town of Jolo is located on the north-west side of the Jolo Island, which is located south-west of the tip of Zamboanga Peninsula on Mindanao island. The island is situated between the provinces of Basilan and Tawi-Tawi, bounded by Sulu Sea to the north and Celebes Sea to the south.

Jolo is a volcanic island, which lies at the center of the Sulu Archipelago covering 890 square kilometres (340 sq mi). The Sulu Archipelago is an island chain in the Southwest Philippines between Mindanao and Borneo, which is made up of 900 islands of volcanic and coral origin covering an area of 2,688 square kilometres (1,038 sq mi). There are numerous volcanoes and craters around Jolo with the last known activity (an earthquake assumed resulting from a submarine eruption from an undetermined location) taking place on September 21, 1897, causing devastating tsunamis in the archipelago and western Mindanao.[17][18][8]

Barangays

[edit]Jolo is politically subdivided into 8 barangays . Each barangay consists of puroks while some have sitios.

- Alat

- Asturias

- Bus-Bus

- Takut Takut

- Tulay

- San Raymundo

- Chinese Pier

- Walled City

Climate

[edit]Jolo has a consistently very warm to hot, oppressively humid, and wet tropical rainforest climate (Köppen Af).

| Climate data for Jolo, Sulu | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 27 (81) |

27 (81) |

27 (81) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 27 (81) |

26 (79) |

27 (81) |

27 (81) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

27 (81) |

27 (81) |

27 (81) |

27 (81) |

27 (81) |

27 (81) |

27 (81) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 170 (6.7) |

130 (5.1) |

125 (4.9) |

122 (4.8) |

229 (9.0) |

286 (11.3) |

254 (10.0) |

248 (9.8) |

182 (7.2) |

257 (10.1) |

233 (9.2) |

188 (7.4) |

2,424 (95.5) |

| Average rainy days | 18.3 | 15.3 | 15.2 | 14.6 | 22.8 | 24.0 | 24.3 | 23.3 | 20.5 | 22.6 | 21.9 | 19.3 | 242.1 |

| Source: Meteoblue (modeled/calculated data, not measured locally)[19] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1903 | 44,718 | — |

| 1918 | 20,230 | −5.15% |

| 1939 | 12,571 | −2.24% |

| 1948 | 18,282 | +4.25% |

| 1960 | 33,259 | +5.11% |

| 1970 | 46,586 | +3.42% |

| 1975 | 37,623 | −4.19% |

| 1980 | 52,429 | +6.86% |

| 1990 | 53,055 | +0.12% |

| 1995 | 76,948 | +7.21% |

| 2000 | 87,998 | +2.92% |

| 2007 | 140,307 | +6.65% |

| 2010 | 118,307 | −6.02% |

| 2015 | 125,564 | +1.14% |

| 2020 | 137,266 | +1.89% |

| 2024 | 152,067 | +2.49% |

| Source: Philippine Statistics Authority[20][21][22][23][24] | ||

Languages

[edit]The majority of people who live in Jolo speak Tausug. English is also used, especially in schools and different offices. Hokkien and Malay are also spoken by some traders. Other languages include Sama and Yakan, while Chavacano is also spoken by Christian and Muslim locals who maintain contacts and trade with the mainland Zamboanga Peninsula and Basilan.

According to the 2000 Philippine census by the Philippine Statistics Authority, the Tausug language ranks number 14 with 1,022,000 speakers all over the country, the speakers mainly in the Western Mindanao area to which Sulu belongs.

Religion

[edit]About 99%[25] of the people living in Jolo practice Islam, but there is also a significant Christian minority consisting of Roman Catholics and Protestants. Tausugs were the first Filipinos to adopt Islam when the Muslim missionary Karim ul-Makhdum came to Sulu in 1380. Other missionaries included Rajah Baguinda and the Muslim Arabian scholar Sayid Abu Bakr, who became the first Sultan of Sulu. The family and community relations are based on their understanding of Islamic law. The Tausug are also heavily influenced by their pre-Islamic traditions.

Tulay Central Mosque is the largest mosque in town and in the province. There are also numerous mosques located in different areas and barangays around Jolo. Our Lady of Mount Carmel Cathedral is a Roman Catholic cathedral located in the town center and is the biggest church in town. "Jolo Alliance Evangelical Church" (formerly known as Jolo Evangelical Church) of the Christian and Missionary Alliance Churches of the Philippines (CAMACOP) also co-exist along with the Catholic Church since the 1900s, making it the first Protestant church in the archipelago.

Culture

[edit]Bangsamoro or Moroland is the homeland of the Moro, which is a Spanish term used for Muslims. The majority of Jolo's people are Tausugs – the ethnic group that dominates the Sulu Archipelago. Tausug derives from the words tau meaning “man” and sug meaning “current”, which translates to “ people of the current”, because they were known to be seafarers with military and merchant skills. The Tausugs are known as the warrior tribe with excellent fighting skills.[26]

Before the Tausugs adopted Islam, the Tausugs were organized into kauman and were governed by a patriarchal form of government with the individual datus as heads of their own communities. The source of law was the Adat which the Tausugs followed strictly.[27]

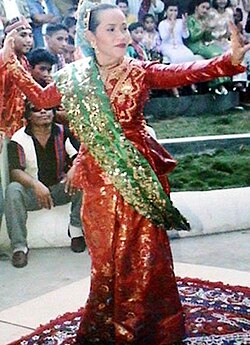

The Tausug arts and handicrafts have a mix of Islamic and Indonesian influences. Pangalay is a popular celebratory dance at Tausug weddings, which can last weeks depending on the financial status and agreement of the families. They dance to the music of kulintangan, gabbang, and agong. Another traditional dance of courtship is the Pangalay ha Agong. In this dance, two Tausug warriors compete for the attention of a woman using an agong (large, deep, brass gong) to demonstrate their competence and skill.[26]

A large portion of the population in Jolo is of Chinese descent. Between 1770 and 1800, 18,000 Chinese came from South China to trade and many of them stayed. In 1803, Portuguese Captain Juan Carvalho reported that there were 1,200 Chinese living in the town. The reorientation of the Sulu trade patterns caused an influx of Chinese immigrants from Singapore.[14]

Economy

[edit]Poverty Incidence of Jolo

10

20

30

40

50

60

2000

43.02 2003

39.14 2006

43.30 2009

46.11 2012

48.37 2015

40.68 2018

58.94 2021

53.14 Source: Philippine Statistics Authority[28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35] |

Industry

[edit]In Jolo, most of the residents are in the agriculture industry. Agricultural products include coconut, cassava, abaca, coffee, lanzones, jackfruit, durian, mangosteen and marang. Jolo is the only municipality in Sulu that does not farm seaweed. Fishing is the most important industry; otherwise people engage in the industries of boat building, mat weaving, coffee processing, and fruit preservation.[36]

Banking

[edit]There were different banks operating in Jolo and serving the people of Jolo for their needs. These included the Philippine National Bank, Metrobank, Allied Bank, Al-Amanah Islamic Bank, Land Bank and Development Bank of the Philippines. Automated teller machines (ATMs) are also available in selected bank branches.

Economic growth

[edit]

Economic development in Jolo has been hampered by instability, violence and unrest caused by the presence of several Islamist separatist groups in the Bangsamoro. The long-running separatist insurgency has made these Muslim-dominated islands some of the poorest regions in the nation.[37] Jolo has faced a large degree of lawlessness and poverty.[38] Jolo is once the main stronghold for the Al-Qaeda-linked Abu Sayyaf terror group, and these conditions are ideal for militant recruitment. However, the situation has improved especially after 2024 since the US contribution to the Operation Enduring Freedom – Philippines and involvement of foreign investors from other countries to improve social condition and developing the region's economy together with increased military operations and security from the Philippine authorities that greatly weaken the Abu Sayyaf and deplete their former source of income from criminal activities.[39][40][41]

In 2007, United States Undersecretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs Karen Hughes and US Ambassador Kristie Kenney visited Jolo to learn about US government-sponsored projects for ‘development, peace and prosperity’ in the region. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has funded a ‘farm-to-market’ road between Maimbung and Jolo to help farmers transport agricultural produce to the market. On her visit, Kenney announced the $3 million plan to improve the Jolo Airport.[42] Since 1997, USAID has spent $4 million a year in the region.[43] Other institutions involved are the World Bank, JICA and AusAID.

The Filipino government has spent over P39 million for development and infrastructure in Sulu.[44] In October 2008, the Provincial Government of Sulu in cooperation with the Local Water Utilities Administration (LWUA), the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the Mindanao Economic Development Council (MEDCO) and the Jolo Mainland Water District (JMWD) started the construction of a 54 million pesos project to upgrade the water supply system in Jolo.[45]

Peace and order

[edit]Clan feud

[edit]In present-day Sulu, there is a degree of lawlessness and clan-based politics. These clan lines are based along family ties, which started after Arthur Amaral proposed marriage to a woman from a rival clan. The rejected proposal caused a family feud which forced families to take sides. There are 100,000 rifles circling the Sulu archipelago. Almost every household owns a gun, and the clans often settle disputes with violence. Most of the disputes between clans revolve around land. The clan-based society makes it extremely difficult for police to impose law. There are several gun shootings and the Filipino Army is often called in to settle disputes.[46] In April 2008, the Jolo Zone of Peace, which was supported by the Geneva-based Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (CHD), was established where firearms were restricted in mediating conflicts between clans. The Sulu government is attempting to spread this zone of peace into the countryside.[47]

Abu Sayyaf

[edit]The island was considered dangerous for foreigners, especially Americans, as militants threatened to shoot or abduct them on the spot. Much of the anger comes from when American colonizers killed 1000 men, women and children, who had retreated up Mount Dajo in 1906 after refusing to pay taxes, in the First Battle of Bud Dajo during the Philippine–American War.[48] However, the American image has improved since American development plans for the region were carried out.

The most radical separatist Islamic group Abu Sayyaf claims to be fighting for an Islamic state independent of the Roman Catholic Philippine government. The group has strongholds in Jolo and Basilan. Driven by poverty and high rewards, a significant number of local residents are suspected to work for them. The Abu Sayyaf has committed a series of kidnappings. On April 23, 2000, the Abu Sayyaf raided the Malaysian resort island of Sipadan and kidnapped 21 tourists from Germany, France, Finland and South Africa and brought them back to Jolo, asking for $25 million in ransom money. The Abu Sayyaf has also kidnapped several journalists and photographers in Jolo. The US has already spent millions of dollars for information leading to the arrest of militants; and offered up to $5 million in bounty with Manila as much as P10 million reward for information leading to the capture of Abu Sayyaf leaders.

Sulu governor Benjamin Loong supported the US Special Forces projects “Operation Smiles” of providing medical care, and building roads and schools. The US Special Forces and Governor Loong hopes that winning respect and alleviating poverty from the people will stop terrorist recruitment. Governor Loong claimed that many residents have turned away Abu Sayyaf and Jemaah Islamiah members.[48]

War on terror

[edit]Three months after the September 11 attacks, George W. Bush announced the US was opening a second front in the war on terror in the Philippines. The Archipelago became the testing grounds for the Philippine anti-terror plan “Clear, Hold and Develop”. In August 2006, Operation Ultimatum was launched and 5,000 Philippine marines and soldiers, supported by the US Special Forces began clearing the island of Jolo, fighting against a force of 400 guerillas. By February 2007, the town of Jolo was deemed cleared of terrorists.

2019 cathedral bombings

[edit]On 27 January 2019, two bombings took place at the Cathedral of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. The bombings led by an unknown bandit but not exactly group Abu Sayyaf were widely condemned by local people in Jolo. The bombing caused at least few people killed or wounded during that day.[citation needed]

2020 town plaza bombings

[edit]On 24 August 2020, at around 12:00 pm, a bomb exploded in front of the Paradise Food Plaza in Barangay Walled City. At least five civilians and four soldiers were killed, while several others were wounded. A second bomb exploded at around 1:00 pm near the Cathedral of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, which was the same site of two bombings last year. One civilian was killed while two others were injured. Philippine Red Cross Chief Richard Gordon said that a motorcycle loaded with an improvised explosive device exploded near a military truck.[49][50][51]

Political and societal significance

[edit]

The Moros are geographically concentrated in the Southwest of the Philippines. Moros identify mostly with the majority Muslim nations of Indonesia and Malaysia because of their geographic proximity, and linguistic and cultural similarities. Moros have faced encroachments from the Spanish, Americans and now face the national Philippine government. Thus, the struggle for the Moro independent state has existed for over 400 years.

Jolo has been the center of this conflict. Between 1972 and 1976, Jolo was the center of the Muslim Separatist Rebellion between the Muslim militants and the Marcos regime which killed 120,000 people. In 1974, fighting broke out when the government troops stopped the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) from taking over the town.[52]

Currently, the Moro National Liberation Front is the ruling party of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM). In 1996, the MNLF was granted leadership of the ARMM in response to the calls for Muslim autonomy. Abdusakur Tan is the governor of Sulu and Edsir Tan is the mayor of Jolo. Politicians in these regions rose to power with the help of clan connections.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "[Act No. 38] AN ACT providing for the organization and government of the municipalities of Jolo, Siassi and Cagayan de Sulu" (PDF). Report of the Governor of the Moro Province.: 69–70. 11 February 1904. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ Municipality of Jolo | (DILG)

- ^ "2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. Quezon City, Philippines. August 2016. ISSN 0117-1453. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 25, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2024 Census of Population (POPCEN) Population Counts Declared Official by the President". Philippine Statistics Authority. 17 July 2025. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- ^ "PSA Releases the 2021 City and Municipal Level Poverty Estimates". Philippine Statistics Authority. 2 April 2024. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ "2024 Census of Population (POPCEN) Population Counts Declared Official by the President". Philippine Statistics Authority. 17 July 2025. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- ^ Saleeby, Najeeb M. (1908). The History of Sulu. p. 133.

- ^ a b c Ang, Josiah C. "Historical Timeline of the Royal Sultanate of Sulu Including Related Events of Neighboring Peoples". Center for Southeast Asian Studies Northern Illinois University.

- ^ James Francis Warren (2007). The Sulu zone, 1768–1898: the dynamics of external trade, slavery, and ethnicity in the transformation of a Southeast Asian maritime state (2, illustrated ed.). NUS Press. pp. 129, 130, 131. ISBN 978-9971-69-386-2.

- ^ James Francis Warren (2007). The Sulu zone, 1768–1898: the dynamics of external trade, slavery, and ethnicity in the transformation of a Southeast Asian maritime state (2, illustrated ed.). NUS Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-9971-69-386-2.

- ^ James Francis Warren (2007). The Sulu zone, 1768–1898: the dynamics of external trade, slavery, and ethnicity in the transformation of a Southeast Asian maritime state (2, illustrated ed.). NUS Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-9971-69-386-2.

- ^ Controversy exists over terminology used in the Spanish-language and Tausug-language versions of the treaty and whether Spain was given complete sovereignty over the Sulu archipelago, including Basilan, or whether a "protectorate-ship" was entered into

- ^ Spanish text of treaty can be viewed in Coleccion de los tratados, convenios y documentos internationales, text also published in the Gaceta de Manila, Año XVlll, Tomo II, numero 0052 Archived 2018-12-28 at the Wayback Machine (August 21, 1878)

- ^ a b James Francis Warren, "The Sulu Zone, 1768–1898: The Dynamics of External Trade, Slavery, and Ethnicity in the Transformation of a Southeast Asian Maritime State". National University of Singapore Press, Singapore.

- ^ a b Santos, Soliman M., Jr. (February 21, 2024). "PEACETALK: The Jolo Siege of 1974, Half a Century Hence: Notes on History, War, Peace, Law and Justice (2)". MindaNews. Archived from the original on 2025-02-18. Retrieved 2025-08-23.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Gutoman, Dominic (2024-02-15). "Survivors muster courage to retell horrors of Jolo siege". Bulatlat. Archived from the original on 2025-01-25. Retrieved 2025-08-23.

- ^ "Eruption history of Jolo" Archived 2012-10-12 at the Wayback Machine. Global Volcanism Program.

- ^ U.S. Bureau of Census. "Census of the Philippine Islands, 1903", pp.217–218. Government Printing Office, 1905.

- ^ "Jolo, Sulu : Average Temperatures and Rainfall". Meteoblue. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ "2024 Census of Population (POPCEN) Population Counts Declared Official by the President". Philippine Statistics Authority. 17 July 2025. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- ^ Census of Population (2015). Highlights of the Philippine Population 2015 Census of Population. Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ Census of Population and Housing (2010). Population and Annual Growth Rates for The Philippines and Its Regions, Provinces, and Highly Urbanized Cities (PDF). National Statistics Office. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ Censuses of Population (1903–2007). Table 1. Population Enumerated in Various Censuses by Region: 1903 to 2007. National Statistics Office.

- ^ "Province of". Municipality Population Data. Local Water Utilities Administration Research Division. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ Philippine Statistics Authority (July 26, 2017). "Muslim Population in Mindanao (based on POPCEN 2015". Archived from the original on May 4, 2019. Retrieved Aug 31, 2018.

- ^ a b "People, Culture and the Arts" Archived 2011-10-05 at the Wayback Machine. Province of Sulu Official Web Site.

- ^ Kamlian, Jamail A.. "Islam, Women and Gender Justice: A Discourse on the Traditional Islamic Practices among the Tausug in Southern Philippines" Archived 2010-06-14 at the Wayback Machine. Emory University School of Law, Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.A.

- ^ "Poverty incidence (PI):". Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ "Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. 29 November 2005.

- ^ "2003 City and Municipal Level Poverty Estimates" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. 23 March 2009.

- ^ "City and Municipal Level Poverty Estimates; 2006 and 2009" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. 3 August 2012.

- ^ "2012 Municipal and City Level Poverty Estimates" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. 31 May 2016.

- ^ "Municipal and City Level Small Area Poverty Estimates; 2009, 2012 and 2015". Philippine Statistics Authority. 10 July 2019.

- ^ "PSA Releases the 2018 Municipal and City Level Poverty Estimates". Philippine Statistics Authority. 15 December 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "PSA Releases the 2021 City and Municipal Level Poverty Estimates". Philippine Statistics Authority. 2 April 2024. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ "Tourism" Archived 2011-10-05 at the Wayback Machine. Province of Sulu Official Web Site.

- ^ McGeown, Kate (February 14, 2013). "Sulu: The islands that are home to Philippine militancy". BBC News. Retrieved December 23, 2024.

- ^ Crossette, Barbara (1987-09-11). "In Filipino Port, Lawlessness Grows". New York Times.

- ^ Cordero, Ted (July 6, 2024). "Marcos hails AFP troops in Mindanao for weakening Abu Sayyaf". GMA News. Retrieved December 23, 2024.

- ^ Maiten, Jeoffrey (December 2, 2024). "Is the Philippines' Sulu province reborn after years of Abu Sayyaf horrors?". South China Morning Post. Retrieved December 24, 2024.

- ^ San Diego, Martin; Tan, Rebecca (December 24, 2024). "Once a war zone, southern Philippines rebrands as tourist destination". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ http://www.lexisnexis.com/us/lnacademic/results/docview/docview.do?docLinkInd=true&risb=21_T5667574747&format=GNBFI&sort=DATE,A,H&startDocNo=1&resultsUrlKey=29_T5666963374&cisb=22_T5667573664&treeMax=true&treeWidth=0&csi=173384&docNo=2[full citation needed]

- ^ "The Official Website of the Provincial Government of Sulu". Archived from the original on 2009-05-12. Retrieved 2009-02-15.[full citation needed]

- ^ "The Official Website of the Provincial Government of Sulu". Archived from the original on 2009-05-12.

- ^ (2008-09-25). "P54-million water supply project for Jolo mainland" Archived 2012-03-03 at the Wayback Machine. Local Water Utilities Administration.

- ^ AlJazeeraEnglish (2008-07-29). "People and Power - Gun culture - 29 July 08 Part 1". YouTube.

- ^ AlJazeeraEnglish (2008-07-29). "People and Power - Gun culture - 29 July 08 Part 2". YouTube.

- ^ a b http://www.lexisnexis.com/us/lnacademic/results/docview/docview.do?docLinkInd=true&risb=21_T5667574747&format=GNBFI&sort=DATE,A,H&startDocNo=1&resultsUrlKey=29_T5666963374&cisb=22_T5667573664&treeMax=true&treeWidth=0&csi=11314&docNo=3[full citation needed]

- ^ "Nine killed in Jolo bombing in southern Philippines". Al Jazeera. 2020-08-24. Retrieved 2020-08-24.

- ^ "At Least 10 Killed After 2 Blasts Rip Through Southern Philippines". The New York Times. 2020-08-24. Retrieved 2020-08-24.

- ^ "4 soldiers killed, 17 others wounded from explosion in barangay in Jolo, Sulu". CNN Philippines. 2020-08-24. Archived from the original on 2020-08-24. Retrieved 2020-08-24.

- ^ Garrido, Marco C. (2005-01-20). "Tribulation Islands, Part 2". Asia Times.

External links

[edit]Jolo, Sulu

View on GrokipediaEtymology

Name origins and historical usage

The name "Jolo" derives from the Tausug term sulug or sūg, an archaic word denoting strong sea currents, alluding to the powerful tidal flows and surrounding coral reefs that define the island's maritime geography. This linguistic root reflects the Tausug people's historical adaptation to the challenging waters of the Sulu Archipelago, where navigation relied on understanding local currents for trade and fishing.[4][9] Earliest documented references to Jolo appear in Chinese historical records from the 13th and 14th centuries, transcribed as "Su-lu," portraying it as a key trading entrepôt facilitating exchanges between Chinese merchants and Southeast Asian polities during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). These mentions, found in annals detailing tribute missions and commerce, highlight Jolo's pre-Sultanate prominence in regional spice, pearl, and slave trades, with archaeological evidence of Chinese ceramics corroborating sustained contact by the late 1300s.[10] With the establishment of the Sulu Sultanate around 1450 under Sharif ul-Hashim, the name Sūg (rendered as Sulu in Arabic-influenced documents) was formalized as the official designation for the island and its central settlement in sultanate charters and diplomatic correspondences, solidifying Jolo's status as the political and economic core of the realm. This usage persisted in treaties with neighboring powers like Brunei, where Jolo served as the primary venue for negotiations over maritime boundaries and tribute rights.[4][10]History

Pre-colonial and Sultanate era

The Sulu Sultanate was established around 1450 CE by Sharif ul-Hashim, an Arab sayyid also known as Sayyid Abu Bakr, who arrived in the Sulu Archipelago and married into local leadership to found the polity blending Islamic governance with indigenous Tausug customs and kinship structures.[11][12] Jolo, the principal settlement on Jolo Island, emerged as a central hub early in the sultanate's history, serving as a key administrative and economic center after initial capitals like Maymbung and Bwansa.[4] The sultanate's rulers, titled sultans, consolidated authority over the archipelago through alliances, religious propagation, and maritime prowess, fostering a multi-ethnic society of Tausug core groups alongside Sama-Bajau seafarers and imported laborers.[13] Economic prosperity underpinned the sultanate's regional dominance, driven by maritime trade networks linking Sulu to China, Southeast Asia, and beyond. Pearl diving in Sulu's reefs supplied high-value pearls exported primarily to Chinese markets, while sea cucumber (trepang) and shark fins were harvested for similar lucrative trade.[14] The slave trade formed a critical component, with raids yielding captives used for diving, agriculture, and resale, integrating Visayan, Borneo native, and other ethnic groups into the economy as dependent laborers.[15] Imports included Chinese porcelain, textiles, and metalware, alongside Arabian influences via intermediaries, enhancing elite status and state revenues through tariffs and tribute.[16] Naval capabilities enabled expansive raids on coastal settlements in the Spanish-controlled Visayas and northern Borneo, securing slaves, tribute, and territorial influence without yielding to external suzerainty. These operations, conducted via swift prahu vessels crewed by warrior-traders, asserted de facto independence and extended Sulu's sway over trade routes in the Sulu Sea, peaking in the 18th-19th centuries before colonial pressures.[4][17] Such activities not only bolstered manpower and wealth but also reinforced the sultanate's identity as a maritime power, deterring rivals through demonstrated military reach.[16]Spanish colonial period

In 1578, Spanish Governor-General Francisco de Sande dispatched Captain Esteban Rodríguez de Figueroa with a fleet and troops to subdue the Sulu Archipelago, including Jolo, aiming to establish vassalage over the Sultanate and counter Moro raids on Christian settlements.[18] The expedition captured temporary footholds but faced fierce resistance from Tausūg warriors, who leveraged knowledge of local waters and terrain for ambushes, forcing a withdrawal without securing lasting control due to overstretched supply lines and high casualties from combat and disease.[4] Subsequent campaigns, such as the 1635–1646 efforts under Governor-General Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera, temporarily occupied Jolo with garrisons and forts but collapsed amid relentless Moro counterattacks and logistical strains, including vulnerability to supply disruptions across the sea lanes from Manila.[4] By the 19th century, intensified sieges culminated in the 1876 expedition led by Admiral José Malcampo, involving over 7,000 troops and naval bombardment that razed Jolo's defenses, including the Sultan's fort and Datu Daniel's stronghold, compelling Sultan Jamalul Azam to sign a peace treaty acknowledging Spanish sovereignty.[19] Yet effective dominion remained limited to coastal forts like those encircling Jolo town, as Tausūg forces reverted to guerrilla warfare—employing swift boat raids and hit-and-run tactics in the archipelago's mangroves and islands—which exploited Spanish overextension and unfamiliarity with the environment, preventing inland pacification.[4] Spanish naval blockades curtailed Jolo's role as a regional trade entrepôt for pearls, slaves, and spices, redirecting commerce and eroding the Sultanate's economic base, though smuggling persisted via agile praus evading patrols.[4] Concurrently, Chinese immigration surged in the late 1800s, with settlers from Fujian establishing merchant communities in Jolo under Spanish tolerance, drawn by tobacco plantations like Hacienda Gomantong (1884–1889) and acting as intermediaries in trade that buffered direct confrontations between garrisons and Moro heartlands. This demographic layer, numbering in the hundreds by 1881, complicated full conquest by fostering hybrid economic zones less amenable to total militarization.American colonial period

Following the Spanish evacuation, United States forces established control over Jolo on May 21, 1899, as part of the broader campaign to secure the Philippine archipelago after the Spanish-American War.[20] The Bates Treaty of August 1899 with Sultan Jamalul Kiram II ostensibly secured Moro neutrality by promising respect for Islamic customs and internal autonomy, but American authorities pursued disarmament and administrative integration, sparking sustained resistance in the Sulu Archipelago.[21] This culminated in the Moro Rebellion (1902–1913), characterized by fierce guerrilla warfare from Moro fighters employing fortified cottas (strongholds) and juramentado suicide attacks against U.S. troops.[22] American pacification relied on overwhelming military superiority, including artillery and organized infantry, to dismantle Moro resistance despite the terrain's challenges and warriors' fanaticism. Key engagements included the Battle of Bud Dajo in March 1906, where forces under Major General Leonard Wood assaulted a volcanic crater stronghold, resulting in over 600 Moro deaths, including non-combatants, effectively shattering large-scale organized opposition on Jolo.[23] Under Brigadier General John J. Pershing, who served as governor of Moro Province from 1909, U.S. troops enforced a 1911 disarmament law mandating surrender of firearms and bladed weapons, confiscating thousands and prompting final holdouts.[23] The Battle of Bud Bagsak in June 1913 saw Pershing's forces eliminate nearly 500 entrenched Moros, marking the rebellion's effective end.[22] Pershing's administration suppressed juramentado attacks—fanatical charges by Moro warriors seeking martyrdom—through policies emphasizing immediate lethal force without capture or negotiation, drastically reducing their frequency.[24] Complementing coercion, U.S. efforts introduced infrastructure vital for control: roads penetrated remote interiors, facilitating troop movement and economic integration, while schools and public markets promoted education and trade, fostering gradual acceptance among the populace.[23] These measures, grounded in respecting Moro Islamic practices while asserting civil authority, transitioned governance from military to civilian oversight by 1914, securing long-term stability through combined force and development.[23]Post-independence developments

Upon the Philippines' attainment of independence on July 4, 1946, Jolo and the Sulu Archipelago were integrated into the republic, overriding longstanding Moro autonomy under the Sultanate of Sulu and earlier petitions to the United States opposing such incorporation.[25][26] This assimilation sowed seeds of resentment, as national policies emphasized centralized governance and Christian migration to Mindanao, marginalizing Moro land rights and cultural distinctiveness without effective mechanisms for Moro self-determination.[26] Escalating grievances fueled the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) uprising in the early 1970s, with Jolo emerging as a focal point of resistance against perceived Manila dominance. The February 1974 Battle of Jolo saw MNLF forces seize key areas, prompting a fierce Philippine military counteroffensive that razed much of the town through artillery and naval bombardment, resulting in an estimated 1,000–20,000 deaths, the destruction of over 80% of structures, and mass displacement of Tausug residents.[27][28][26] President Ferdinand Marcos's declaration of martial law on September 23, 1972, extended to Sulu, intensifying counterinsurgency operations that displaced tens of thousands of Tausug civilians and triggered refugee flows to neighboring Sabah, Malaysia.[26][29] These upheavals, compounded by internal fractures among Moro factions unable to unify beyond short-term alliances, perpetuated cycles of violence and eroded Jolo's pre-war role as a trade hub, fostering chronic economic underdevelopment marked by collapsed infrastructure, disrupted pearl and marine economies, and persistent poverty rates exceeding 70% in Sulu province by the 2000s.[29][30] Efforts at resolution, such as the 1976 Tripoli Agreement granting limited autonomy, faltered amid MNLF divisions and government non-compliance, prolonging stagnation. The 2019 Bangsamoro Organic Law established the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) as a concession to broader Moro separatist aspirations elsewhere in Mindanao, but Sulu's rejection in the January plebiscite—by a margin of 54% against inclusion—excluded the province, reflecting deep-seated distrust of diluted autonomy and elite rivalries that prioritized provincial control over regional federation.[31][32] This outcome, affirmed by the Supreme Court in 2024, left Jolo outside BARMM's framework, sustaining vulnerabilities to insecurity and underinvestment while exposing the causal limits of top-down integration absent genuine devolution of power to address Moro identity and economic disparities.[31]Geography

Physical features and location

Jolo is a volcanic island situated at the center of the Sulu Archipelago in the southwestern Philippines, with approximate coordinates of 6°03′N 121°00′E.[33] It occupies a strategic position between Mindanao to the north and Borneo to the southwest, facilitating control over vital sea lanes in the Sulu Sea that historically supported trade between Southeast Asia and the Pacific.[33] This remote maritime location, isolated from the Philippine mainland by over 200 kilometers of open water, contributed to the island's rugged autonomy by limiting external interference and enabling self-reliant maritime economies centered on fishing and inter-island commerce.[33] The island spans approximately 850 square kilometers, characterized by scattered volcanic mountains rather than continuous ranges, with fertile coastal plains and inland valleys.[34][35] Its highest peak, Mount Dahu, rises to 812 meters, part of the Jolo Group of Volcanoes that includes young cinder cones, explosion craters, and evidence of past eruptions.[33][36] Surrounding coral reefs protect natural harbors, such as those at the main port of Jolo town, which have enabled historical seafaring activities despite the archipelago's exposure to seismic disturbances from the nearby Philippine Trench.[33][36] Geologically active due to its position on the Pacific Ring of Fire, Jolo experiences frequent earthquakes, with historical records noting seismic tides and shocks linked to volcanic unrest.[37] The terrain's elevation and coastal features offer some buffering against typhoons, though the region remains vulnerable to tropical storms tracking through the Sulu Sea, which can exacerbate erosion on the volcanic slopes.[38] This combination of isolation and natural defenses reinforced the island's strategic independence, as difficult access by land or sea deterred large-scale invasions while permitting agile naval defenses.[33]Administrative divisions

Jolo is administratively subdivided into eight barangays: Alat, Asturias, Bus-bus, Chinese Pier, San Raymundo, Takut-takut, Tulay, and Walled City.[1] As of the 2020 census, these barangays had the following populations:| Barangay | Population (2020) |

|---|---|

| Alat | 11,368 |

| Asturias | 26,997 |

| Bus-bus | 38,650 |

| Chinese Pier | 7,718 |

| San Raymundo | 17,051 |

| Takut-takut | 8,123 |

| Tulay | 14,891 |

| Walled City | 12,468 |

Climate and environment

Jolo experiences a tropical rainforest climate (Köppen Af), with consistently high temperatures averaging between 24°C and 32°C year-round, rarely dropping below 22°C, and oppressive humidity levels often exceeding 80%.[41] The island receives abundant rainfall, totaling approximately 2,500 mm annually, distributed relatively evenly throughout the year with no pronounced dry season, contributing to lush vegetation but also frequent flooding risks.[42] High humidity and maritime influences from the surrounding Sulu Sea exacerbate the hot, overcast conditions, fostering a stable but challenging environment for agriculture and settlement.[43] Ecologically, Jolo's environment features volcanic soils supporting limited upland forests, though deforestation from traditional slash-and-burn (kaingin) practices has reduced tree cover, leading to soil erosion and watershed degradation across the Sulu Archipelago. The surrounding Sulu Sea hosts rich marine biodiversity, including coral reefs, seagrass beds, and diverse fish stocks within the Coral Triangle ecoregion, historically renowned for natural pearl oyster beds that sustained trade until overexploitation diminished yields.[44] However, excessive and destructive fishing methods, such as blast and cyanide techniques, have caused habitat degradation, declining catches, and biodiversity loss, underscoring the risks of overreliance on marine resources without sustainable management.[45] These pressures, compounded by coastal development, threaten long-term ecological resilience in the region.[46]Demographics

Population trends

The population of Jolo underwent severe disruption during the 1974 Battle of Jolo, when Philippine government forces clashed with Moro National Liberation Front rebels, resulting in the near-total destruction of the town and massive civilian casualties estimated between 1,000 and 20,000 deaths, alongside the displacement of approximately 40,000 residents, leaving only about 5,000 people in the ruins immediately afterward.[28][47] This event, part of the broader Moro insurgency that intensified in the early 1970s, triggered long-term stagnation in population growth, as recurring violence deterred return migration and economic recovery, with subsequent clashes involving groups like Abu Sayyaf further exacerbating out-migration and hindering natural increase compared to national averages.[48] Census data reflect this muted trajectory: Jolo's population grew modestly from 44,718 in 1903 to 137,266 by the 2020 census, a compound annual growth rate far below the Philippine national figure over the same period.[1] Ongoing security challenges in Sulu province have perpetuated displacement patterns, though Jolo as the provincial capital has periodically seen net inflows of internally displaced persons from rural municipalities fleeing localized violence, contributing to episodic population upticks amid baseline stagnation.[2] Demographically, Jolo mirrors Sulu province's pronounced youth bulge, with a 2010 median age of 19.1 years—meaning half the population was younger than this threshold—and fertility rates elevated above the national average of around 2.0 births per woman, sustained by factors including early marriage prevalent in Muslim communities, where one in six girls in Sulu marries before age 18.[49][50] This structure amplifies pressure on local resources while conflict continues to disrupt stable growth.[51]Ethnic and linguistic composition

The population of Jolo is predominantly composed of the Tausūg ethnic group, which forms the core of the island's demographic makeup as the primary inhabitants of the Sulu Archipelago. In Sulu Province, encompassing Jolo as its capital and principal municipality, Tausūg individuals accounted for 85.27% of the household population in the 2000 census conducted by the Philippine Statistics Authority.[52] Jolo itself exhibits an even higher concentration of Tausūg residents, given its status as the historical and cultural center of the group, with minorities including Sama-Bajau and smaller numbers of migrants from other Philippine regions.[53][54] Linguistically, Tausūg (also known as Bahasa Sug) dominates as the mother tongue for over 90% of Jolo's residents, functioning as the local lingua franca with dialects such as Parianun along the coastal areas including the town proper and Gimbahanun in the interior highlands.[55] Filipino, based on Tagalog, serves as the national lingua franca for inter-regional communication and official purposes. Minority languages include Sinama spoken by Sama-Bajau communities and Zamboangueño Chavacano, a Spanish-based creole remnant of colonial trade links with Zamboanga Peninsula ports, used as a second language by some residents engaged in commerce.[56] English proficiency remains low among the populace, with studies of local university students revealing significant challenges in speaking and comprehension that limit access to national economic opportunities and integration.[57][58]Religious demographics

The population of Jolo is overwhelmingly Muslim, with surveys and ecclesiastical estimates indicating that Muslims comprise over 95% of residents in the municipality and surrounding areas of Sulu province.[35] This high proportion reflects the historical dominance of Islam in the Sulu Archipelago, where the faith was introduced through trade and missionary activities starting in the 14th century.[59] Islam in Jolo adheres to the Sunni tradition, specifically the Shafi'i school of jurisprudence, which became entrenched via the Sultanate of Sulu's adoption of orthodox Sunni practices influenced by broader Southeast Asian Islamic networks.[60] The Shafi'i madhhab, emphasizing scriptural sources and analogical reasoning, shapes local interpretations of Islamic law, though adherence varies with traditional and reformist influences.[61] A small Christian minority, primarily Roman Catholics, accounts for approximately 1.6% of the population in the Apostolic Vicariate of Jolo, which includes Sulu and Tawi-Tawi islands as of 2023.[35] This group descends largely from colonial-era migrations and conversions, maintaining a presence despite historical claims of religious tolerance under the sultanate, contrasted by periodic sectarian tensions evidenced in attacks on Christian sites.[62] Other religious affiliations, such as animist beliefs among indigenous groups, are negligible in contemporary demographics.

.jpg/250px-Tulay_Central_Mosque_night_view_(Serantes,_Jolo,_Sulu;_10-10-2023).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-Tulay_Central_Mosque_night_view_(Serantes,_Jolo,_Sulu;_10-10-2023).jpg)