Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

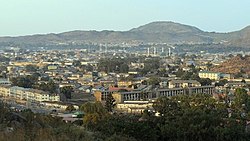

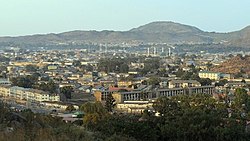

Jos /ˈdʒɔːs/ is a city in the North-Central region of Nigeria. The city has a population of about 900,000 residents based on the 2006 census.[2] Popularly called "J-Town",[3] it is the administrative capital and largest city of Plateau State. The city is situated on the Jos plateau which lies within the Guinea Savannah of North-Central Nigeria. It connects most of the North-Eastern capitals to the Federal Capital Territory Abuja, by road. Driving in and out of Jos, traffic encounters very steep and windy bends and mountainous sceneries typical of the plateau, from which the state derives its name.

Key Information

During the period of British colonial rule, Jos became an important centre for tin mining after large deposits of cassiterite, the main ore for the metal, were discovered. It is also the trading hub of Plateau State as commercial activities are steadily increasing.

History

[edit]The earliest known settlers of the land that would come to be known as Nigeria were the Nok people (c. 1000 BC), skilled artisans from around the Jos area who mysteriously vanished in the late first millennium.[4]

According to the historian Sen Luka Gwom Zangabadt,[5] the area known as Jos today was inhabited by indigenous ethnic groups who were mostly farmers. During the British colonial period, direct rule was introduced for the indigenous ethnic groups on the Jos Plateau since they were not under the Fulani emirates where indirect rule was used.[6] According to the historian Samuel N Nwabara, the Fulani empire controlled most of northern Nigeria, except the Plateau province and the Berom, Ngas, Tiv, Jukun and Idoma ethnic groups.[7] It was the discovery of tin by the British that led to the influx of other ethnic groups such as the Hausa from the north, southeastern Igbo, and Yoruba from the country's southwest. As such, Jos is often recognised as a cosmopolitan Nigerian city.

According to the white paper of the commission of inquiry into the 1894 crisis, Ames, a British colonial administrator, said that the original name for Jos was Gwosh in the Izere language (spoken by the Afusari, the first settlers in the area), which was a village situated at the current site of the city; according to Ames, the Hausa, who arrived there after, wrongly pronounced Gwosh as "Jos" and it stuck.[8] Another version was that "Jos" came from the word "Jasad" meaning body in Arabic. To distinguish it from the hilltops, it was called "Jas", which was mispronounced by the British as "Jos". It grew rapidly after the British discovered vast tin deposits in the vicinity. Both tin and columbite were extensively mined in the area up until the 1960s. They were transported by railway to both Port Harcourt and Lagos on the coast, and then exported from those ports. Jos is still often referred to as "Tin City". It was made capital of Benue-Plateau State in 1967 and became the capital of the new Plateau State in 1975. Jos has become an important national administrative, commercial, and tourist centre. Tin mining led to the influx of migrants (mostly Igbos, Yorubas and Europeans) who constitute more than half of the population of Jos. This "melting pot" of race, ethnicity and religion makes Jos one of the most cosmopolitan cities in Nigeria. For this reason, Plateau State is known in Nigeria as the "home of peace and tourism".

Excellent footage of Jos in 1936 including the tin mines, local people and the colonial population is held by the Cinema Museum in London [ref HM0172].

Political divisions

[edit]

The city is divided into 2 local government areas of Jos North and Jos South. The city proper lies between Jos North and parts of Jos South headquartered in Bukuru.

- Jos-North

The Local Government Council administration is headquartered here. Jos North is the commercial nerve centre of the state as it houses the state's branch of Nigeria's Central Bank and the headquarters of the commercial banks are mostly located here as well as the currency exchanges along Ahmadu Bello Way. Moreover, all basic and essential services can be found in Jos North from the Jos Main market (terminus) to the Kabong or Rukuba Road satellite market. Due to recent communal clashes, however, a lot of commercial activities are shifting to Jos South.

The palace and office of the Gbong Gwom Jos (traditional ruler of Jos) are located in an area in Jos North called Jishe in the Berom language. In 1956, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II together with her consort Prince Philip had a weekend stopover to rest at Jishe during her Nigeria tour.[9] Jishe was known at that time as Tudun Wada cottage. Jos North has a significant slum.[10] Jos North is the location of the University of Jos and its teaching hospital at Laminga & the National Commission for Museums and Monuments. The Nigerian Film Institute is also located in Jos-North at the British America junction along Murtala Mohammed way. Both the Evangelical Church Winning All (ECWA) and the Church of Christ in Nations (COCIN) are headquartered in this part of the metropolis.

- Jos-South

Jos South is the second most populous Local Government Area in Plateau State and has its Council located along Bukuru expressway. Jos South is the seat of the Governor i.e. the old Government House in Rayfield and the New Government House in Little Rayfield and the industrial centre of Plateau State due to the presence of industries like the NASCO group of companies, Standard Biscuits, Grand Cereals and Oil Mills, Zuma steel west Africa, aluminium roofing industries, Jos International Breweries among others. Jos South also houses prestigious institutions like the National Institute of Policy and Strategic Studies (NIPSS), the highest academic awarding institution in Nigeria, the Police Staff College, the NTA television college, Nigerian Film Corporation and Karl Kumm University. Jos South also houses the prestigious National Centre For Remote Sensing. The city has formed an agglomeration with the town of Bukuru to form the Jos-Bukuru metropolis (JBM). Jos also is the seat of the famous National Veterinary Research Institute (NVRI), situated in Vom.[11] and the Industrial Training Fund (ITF).

Geography and climate

[edit]Situated almost at the geographical centre of Nigeria and about 179 kilometres (111 miles) from Abuja, the nation's capital, Jos is linked by road, rail and air to the rest of the country. The city is served by Yakubu Gowon Airport, but its rail connections no longer operate as the only currently operational section of Nigeria's rail network is the western line from Lagos to Kano.

At an altitude of 1,217 m (3,993 ft) above sea level, Jos' climate is closer to temperate than that of the vast majority of Nigeria. Average monthly temperatures range from 21–25 °C (70–77 °F), and from mid-November to late January, night-time temperatures drop as low as 7 °C (45 °F). Hail sometimes falls during the rainy season because of the cooler temperatures at high altitudes.[12] These cooler temperatures have, from colonial times until the present day, made Jos a favourite holiday location for both tourists and expatriates based in Nigeria.[citation needed]

Jos receives about 1,400 millimetres (55 inches) of rainfall annually, the precipitation arising from both convectional and orographic sources, owing to the location of the city on the Jos Plateau.[13]

According to the Köppen climate classification system, Jos has a tropical savanna climate, abbreviated Aw.[14]

| Climate data for Jos (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1947–1970, 1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 35 (95) |

34.5 (94.1) |

35.6 (96.1) |

36 (97) |

35.3 (95.5) |

32.2 (90.0) |

29.2 (84.6) |

30 (86) |

29.5 (85.1) |

34 (93) |

31.7 (89.1) |

32 (90) |

36.0 (96.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 28.3 (82.9) |

30.2 (86.4) |

31.9 (89.4) |

30.8 (87.4) |

28.4 (83.1) |

26.4 (79.5) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.1 (75.4) |

26.0 (78.8) |

27.5 (81.5) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.9 (82.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 20.0 (68.0) |

22.1 (71.8) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.7 (76.5) |

23.4 (74.1) |

21.9 (71.4) |

20.8 (69.4) |

20.5 (68.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.9 (71.4) |

20.8 (69.4) |

19.8 (67.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 11.8 (53.2) |

14.0 (57.2) |

17.0 (62.6) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.4 (65.1) |

17.5 (63.5) |

17.0 (62.6) |

16.9 (62.4) |

16.8 (62.2) |

16.4 (61.5) |

13.3 (55.9) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.8 (60.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 1.1 (34.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

10 (50) |

12.5 (54.5) |

12 (54) |

13 (55) |

11 (52) |

9.5 (49.1) |

10 (50) |

10.0 (50.0) |

8 (46) |

6 (43) |

1.1 (34.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.4 (0.02) |

5.1 (0.20) |

13.4 (0.53) |

93.2 (3.67) |

176.5 (6.95) |

207.1 (8.15) |

248.7 (9.79) |

255.5 (10.06) |

181.9 (7.16) |

58.7 (2.31) |

1.2 (0.05) |

1.2 (0.05) |

1,242.9 (48.93) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 6.8 | 13.3 | 14.7 | 19.0 | 19.6 | 15.1 | 5.9 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 96.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 21.5 | 20.6 | 28.7 | 52.7 | 70.3 | 76.7 | 81.7 | 86.1 | 83.1 | 73.2 | 47.0 | 29.4 | 55.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 282.1 | 254.8 | 238.7 | 204.0 | 204.6 | 198.0 | 158.1 | 139.5 | 177.0 | 238.7 | 285.0 | 288.3 | 2,668.8 |

| Percentage possible sunshine | 79 | 78 | 64 | 56 | 53 | 53 | 41 | 37 | 49 | 65 | 82 | 81 | 61 |

| Source 1: NOAA (sunshine 1961–1990)[15][16] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: DWD (extremes)[17] | |||||||||||||

Education

[edit]Jos is home to University of Jos one of the largest University in Nigeria. The institution is very prominent in the fields of Agriculture, Science, Finance, Medicine and Law. The school is known for the large number of elites from the region that passed through its academic buildings and counts among its alumni former Nigerian heads of state, Yakubu Gowon.

Jos is also the base for the Nigerian Film Corporation, Federal College of Forestry, NTA TV College, Karl kumm University, Jos University Teaching Hospital, Bingham University Teaching Hospital, Some historic secondary school in the city is the Air force military school.

Features

[edit]- 330 Nigerian Air Force station Jos

the 330 Nigerian Air Force station is located in the Jos South Local Government area along the old airport road. The station boasts blocks of barracks for air personnel, an airstrip, a primary school, a military secondary school and a hospital which is arguably one of the best in the state.

- Jos Wildlife Park

Covering roughly 3 square miles (7.8 km2) of savannah bush and established in 1972 under the administration of then Governor of Benue-Plateau Joseph Gomwalk in alliance with a mandate by the then Organisation of African Unity to African heads of state to earmark one-third of their landmass to establish conservation areas in each of their countries, It has since then become a major attraction in the state, attracting tourists from within and outside the country. The park has become a home to various species of wildlife including Lions, Rock pythons, marabou storks, Baboons, Honey Badgers, Camels as well as variant flora.

- Jos Museum

The National Museum in Jos was founded in 1952 by Bernard Fagg,[18] and was recognized as one of the best in the country. It has unfortunately been left to fall to ruin as is the case with most of the cultural establishments in Nigeria. The Pottery Hall is also a part of the museum that has an exceptional collection of finely crafted pottery from all over Nigeria and boasts some fine specimens of Nok terracotta heads and artefacts dating from 500 BCE to 200 CE. It also incorporates the Museum of Traditional Nigerian Architecture with life-size replicas of a variety of buildings, from the walls of Kano and the Mosque at Zaria to a Tiv village. Articles of interest from colonial times relating to the railway and tin mining can also be found on display. A School for Museum Technicians is attached to the museum, established with the help of UNESCO. The Jos Museum is also located beside the zoo.

- Jos Polo Club

Situated at the end of Joseph Gomwalk Road, the Jos Polo Club is one of the prominent sports institutions in the state.

- Jos Stadium

A 40,000-seat capacity located along Farin-Gada road which has become home to the Plateau United Football Club, Current champions of The Nigerian Professional League. Rwang Pam township stadium Jos.

- Jos Golf Course

The golf course located in Rayfield, Jos has hosted many golfing competitions with players coming from both within and outside the state.

Other local enterprises include food processing, beer brewing, and the manufacture of cosmetics, soap, rope, jute bags, and furniture. Heavy industry produces cement and asbestos cement, crushed stone, rolled steel, and tyre retreads. Jos is also a centre for the construction industry and has several printing and publishing firms. The Jos-Bukuru dam and reservoir on the Shen River provide water for the city's industries.

Jos is a base for exploring Plateau State. The Shere Hills, seen to the east of Jos, offer a prime view of the city below. Assop Falls is a small waterfall which makes a picnic spot on a drive from Jos to Abuja. Riyom Rock is a dramatic and photogenic pile of rocks balanced precariously on top of one another, with one resembling a clown's hat, observable from the main Jos-Akwanga road.[19]

The city is home to the University of Jos (founded in 1975), St Luke's Cathedral, an airport and a railway station. Jos is served by several teaching hospitals including Bingham University Teaching Hospital and Jos University Teaching Hospital (JUTH), a federal government-funded referral hospital.[20] The Nigerian College of Accountancy, with over 3,000 students in 2011, is based in Kwall, Plateau State.[21]

Notable people

[edit]- Third Nigerian Republic President-elect MKO Abiola was elected SDP flag bearer in Jos

- Yakubu Gowon, Nigeria's second military Head of state & hero of the Nigerian civil war. resides in Jos.

- Joseph Gomwalk†, First Governor of Plateau State.

- John Dungs†, residence; Rayfield, Jos.

- Jonah Jang, residence; Du.

- Davou Zang, residence; D. B. Zang junction, Gyel.

- Muhammadu Buhari, President of Nigeria and former GOC 3rd armoured division, of the Nigerian Army, Jos.

- Olusegun Obasanjo, ex Nigerian president was interned in the Nigerian Correctional Service, Jos during Sani Abacha's military junta. Obasanjo later won his PDP presidential ticket in Jos Polo Club.

- Solomon Lar†, residence beach road Jos.

- Michael Botmang†, residence Za'ang.

- Jeremiah Gyang, singer and producer based in Jos.

- Mabo Ismaila, Former coach of the female National Football Team, the Super Falcons

- Segun Odegbami, Nigerian footballer spent his childhood years in Jos

- Delmwa Deshi-Kura, Nigerian film production executive and director, known for her work in television and reality productions.

- Desmond Elliot, Nigerian actor, director and Member of the Lagos State House of Assembly[22][23]

- Ahmed Musa, Nigerian footballer was born in Jos[24][25][26]

- Bez (musician), Nigerian alternative soul singer was born and raised in Jos[27]

- Doug Kazé, Nigerian alternative Afro-soul musician was born and raised in Jos

- Mikel John Obi, international footballer spent his childhood years in Jos[28]

- Ogenyi Onazi, international footballer was born in Jos[29][30]

- Sunday Mba, international footballer had his childhood years in Jos

- Joseph Akpala, international footballer was born in Jos

- Benedict Akwuegbu, international footballer had his childhood years in Jos[31]

- Chibuzor Okonkwo, international footballer was born in Jos

- Ice Prince, Nigerian musical artist grew up in Jos[32]

- Dayo Okeniyi, actor was born in Jos[33]

- M.I, rapper born and raised in Jos[34][35][36]

- Saint Obi, veteran Nollywood actor kicked off his career in Jos[37][34]

- P-Square, Music duo of identical twin brothers Peter Okoye and Paul Okoye were born and raised in Jos.[38][39][40]

- Innocent 'Tuface' Idibia Nigerian multi-award-winning musician was born in Jos[41][34][42][43]

- Deborah Enilo Ajakaiye (born 1940), Nigerian geophysicist

- Sarah Ladipo Manyika (born 7 March 1968), British-Nigerian writer, spent much of her childhood in Lagos and Jos[44]

- Tony Elumelu was born in Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria, in 1963. He hails from Onicha-Ukwu in Aniocha North Local Government Area of Delta State.[45][46]

- Kenneth Gyang, filmmaker who was born in Barkin Ladi of Plateau State, Nigeria.

- John Major, former British Prime Minister, worked in the town from 1966 to 1967.

- Simon Bako Lalong, (born 1963) Nigerian politician and Governor of Plateau State from 2015 to 2023 and the senator representing the Plateau South senatorial district since 2023.[47]

- Saviour Godwin (born 1996), footballer

- Ugochukwu Iwu, Born in Nigeria, he represents Armenia at international level.

- Asha was raised and schooled in Federal Government college, Jos

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "TelluBase—Nigeria Fact Sheet (Tellusant Public Service Series)" (PDF). Tellusant. Retrieved 2024-01-11.

- ^ "Federal Republic of Nigeria : 2006 Population Census" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ "j-town". naijalingo.com. Retrieved 2024-07-05.

- ^ "Nok culture | Iron Age culture". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ History of Jos and political development of Nigeria; Sen Luka Gwom Zangabadt

- ^ Billy J. Dudley. Parties and politics in Northern Nigeria

- ^ Nwabara, Samuel N. The Fulani conquest and the rule of the Hausa kingdom of Northern Nigeria (1804–1900). p. 235.

- ^ Presswire, The New Gong (2017-05-20). "Jos, a city inspired by tin". Things Nigeria. Retrieved 2024-07-05.

- ^ https://www.britishempire.co.uk/article/queensvisittojos.htm [bare URL]

- ^ Madueke, Kingsley L.; Vermeulen, Floris, "Mapping the interworkings of state forces, vigilantes, residents, thugs, and armed mobs in the violent slums of Jos, Nigeria", Limited Statehood and Informal Governance in the Middle East and Africa, doi:10.4324/9780429504570-15, retrieved 2022-12-28

- ^ "National Veterinary Research Institute, Vom, Nigeria". IVVN. Retrieved 2022-12-28.

- ^ admin (2024-07-22). "Brief History". Jos University Teaching Hospital. Retrieved 2025-01-16.

- ^ "Publications" (PDF). Iahs.info. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- ^ "Climate: Jos -a– Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 2013-11-26.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991-2020 — Jos". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 6, 2024.

- ^ "Jos Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ "Klimatafel von Jos / Nigeria" (PDF). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- ^ Man, Vol. 52, Jul. 1952 (Jul. 1952), pp. 107–108

- ^ pictda. "Welcome! Home| Plateau State Government Website". Laravel. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

- ^ "Home | Jos University Teaching Hospital". juth.org.ng. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

- ^ "History The College". ANAN. Archived from the original on 2011-08-11. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- ^ Kabir, Olivia (2021-02-01). "Desmond Elliot's bio: Interesting facts about the famous actor and politician". Legit.ng - Nigeria news. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ Kwach, Julie (2018-01-30). "Desmond Elliot Wife and Kids Pictures; Here's Desmond Elliot Wife and Kids (Pictures)". Tuko.co.ke - Kenya news. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "The Transfer Record: Ahmed Musa". www.lcfc.com. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "Super Eagles captain, Ahmed Musa to build school in Plateau". Vanguard News. 2021-01-06. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "Musa doles out N6M to Jos football tourney - The Nation Newspaper". Latest Nigeria News, Nigerian Newspapers, Politics. 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "Spotlight: Simi, Bez... five alternative artistes that are Covenant University alumni". TheCable Lifestyle. 2018-01-27. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ Soriola, Elizabeth (2021-04-21). "Mikel Obi's biography and the details of his journey to success". Legit.ng – Nigeria news. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ Mutsoli, Vivian (2021-01-05). "Ogenyi Onazi bio: hometown, family background, wife, salary, house". Legit.ng – Nigeria news. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "Ogenyi Onazi: "Football can unify, but bombs tear my people apart"". World Soccer. 2015-04-04. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "MARITAL MESS: Ex-Super Eagles Benedict Akwuegbu, wife, bicker over divorce, second marriage". Latest Nigeria News, Nigerian Newspapers, Politics. 2020-12-06. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "Ice Prince unveils artwork for "Jos to the World (#J2TW)" album | Premium Times Nigeria". 2016-10-15. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "Top 15 Nigerian Actors In The Diaspora You May Not Have Heard About". Nigerian Entertainment Today. 2020-01-21. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ a b c "Nigeria's musical legends of J-Town". The Africa Report.com. 2018-02-16. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "MI Features Oxlade In 'All My Life'". Leadership News - Nigeria News, Breaking News, Politics and more. 2021-06-06. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "Eight top artistes, producers who had their start in Jos". TheCable Lifestyle. 2018-06-14. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "Revelations On Why Saint Obi Left Nollywood and What He Is Up To Now". BuzzNigeria - Famous People, Celebrity Bios, Updates and Trendy News. 2021-04-24. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "Peter Okoye's Solo Journey as Mr P Since Splitting From P-Square". BuzzNigeria – Famous People, Celebrity Bios, Updates and Trendy News. 2021-05-18. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ Kolesnik, Kay (2020-11-20). "Paul Okoye bio: brother, wife, children, solo music career". Legit.ng - Nigeria news. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "Psquare's Breakup Makes No Sense – Charass". Channels Television. 27 September 2017. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "10 things to know about 2face as he turns 42 | Premium Times Nigeria". 2017-09-18. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ Kabir, Olivia (2019-02-18). "Where is 2face from in Nigeria and other top facts about him". Legit.ng – Nigeria news. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "Nigerian Singer 2face Idibia Celebrates 42nd Birthday". allAfrica.com. 2017-09-19. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ Manyika, Sarah Ládípọ̀. "Sarah Ládípọ̀ Manyika". OZY. Archived from the original on 2021-05-17. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "Tony Elumelu @58: The Man, the Entrepreneur, and Philanthropist". THISDAYLIVE. 2021-04-27. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "20 things about Tony Elumelu, man of means who donates billions | Encomium Magazine". 25 August 2017. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ Odeniyi, Solomon (2023-11-07). "BREAKING: Appeal Court declares Lalong winner of Plateau South senatorial poll". Punch Newspapers. Retrieved 2024-03-24.

External links

[edit]Jos is the capital city of Plateau State in central Nigeria, situated on the Jos Plateau at an elevation of approximately 1,200 meters above sea level, which endows it with a cooler, more temperate climate than surrounding lowland areas.[1][2]

Established in the early 20th century as a hub for tin mining under British colonial administration, following the discovery of rich cassiterite deposits around 1904, Jos rapidly grew into a multicultural center attracting laborers from across Nigeria and beyond, including Hausa-Fulani, Yoruba, Igbo, and international migrants.[3][4][5]

The city's economy historically revolved around mineral extraction, peaking in the 1940s with tens of thousands of workers, though mining has declined, leaving environmental legacies such as scarred landscapes and abandoned sites.[6][3]

Today, Jos functions as an administrative, educational, and tourism destination, hosting institutions like the University of Jos and attractions including the Jos Wildlife Park and natural rock formations, amid a diverse ethnic composition that includes indigenous Berom and Afizere alongside settler communities.[7][8]

However, it has been defined by recurrent ethno-religious violence since the early 2000s, often pitting Christian indigenous groups against Muslim Hausa-Fulani settlers over issues of land, political representation, and identity, resulting in significant casualties and displacement.[9][10]