Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Zaria

View on Wikipedia

Zaria (formerly Zazzau) is a metropolitan city in Nigeria, located within four local government areas in Kaduna State. It serves as the capital of the Zazzau Emirate Council and is one of the original seven Hausa city-states. The local government areas comprising Zaria are Zaria, Sabon Gari, Giwa, and Soba local government areas of Kaduna State, Nigeria.

Key Information

It contains Nigeria's largest university, Ahmadu Bello University, and various tertiary institutions including the Federal College of Education (FCE Zaria), Nigerian College of Aviation Technology, Nigerian Institute of Transport Technology, Nigeria Institute of Leather and Science Technology and Nuhu Bamalli Polytechnic. Nigerian College of Aviation Technology. Department of Agriculture Ahmed Bello University Zaria. Ameer Shehu Idris College of Advanced Diploma.

From the 2006 population census, Zaria was estimated to have 736,000 people.[2] It is home to the Emir of Zazzau.

History

[edit]

Zaria, initially known as Zazzau, was the capital of the Hausa kingdom of Zazzau.[3] Zazzau is thought to have been founded in or about 1536 and in the late 16th century it was renamed after Queen Amina's sister, Zaria.[4] Human settlement predates the rise of Zazzau, as the region, like some of its neighbors, had a history of sedentary Hausa settlement, with institutional market exchange and farming.

Zaria was the most southern of the Hausa city-states. It was a trading destination for Saharan caravans as well as a prominent city in the Hausa slave trade. In the late 1450s, Islam arrived in Zaria by the way of its sister Habe cities, Kano and Katsina. Along with Islam, trade flourished between the cities as traders brought camel caravans filled with salt in exchange for slaves and grain. The city-state's power peaked under Queen Amina whose military campaigns established a tributary region including the kingdoms of Kano and Katsina. At the end of the 16th century, after Queen Amina's death, Zaria fell under the influence of the Jukun Kingdom and eventually became a tributary state itself.[3] Between the fifteenth and sixteenth century the kingdom became a tributary state of the Songhai Empire. In 1805 it was captured by the Fulani during the Fulani Jihad. British forces led by Frederick Lugard took the city in 1901.[5]

A French hostage of the Islamist group Ansaru, held captive at Zaria,[6] escaped in 2013 and reached a police station in the city.

In December 2015, Nigeria's military was reported to have killed 300 Shia Muslims and buried their bodies in a mass grave, following their physical attack and blockade of the Chief of Army Staff, General Tukur Yusuf Burtai in an area they claimed to own as they don't recognize the leadership of the Republic of Nigeria. Although the government denies the killing part, it has been described as a massacre.[7]

Cityscape

[edit]

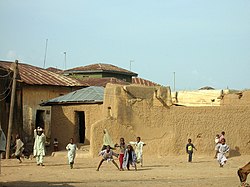

The old part of the city, known as Birnin Zazzau[8] or Zaria City, was originally surrounded by walls and fortress, which have been mostly removed.[9] The Emir's palace is in the old city. In the old city and the adjacent Tudun Wada neighbourhood people typically reside in traditional adobe compounds. These two neighborhoods are predominantly occupied by the indigenous Hausa.[8]

There is great variety in the architecture of Zaria, with buildings made of clay in the Hausa style juxtaposed with modern, multi-storied university and government buildings.[4]

Silk-cotton tree is one of the largest trees in Zazzau emirate generally and the tree has played an important role in the spiritual and economic lives of the peoples who live in Zaria especially people of Anguwan Kahu who makes Kahu for the Emirs, district heads, ward heads and village heads. silk-cotton-tree-scientific-name-is-ceiba-pentandra-under-blue-sky.

Anguwan Kahu was known to be a place of business where it use cotton to make local mattresses, pillows, Horse shirts etc.

Wakilin Kahu Zazzau is the head of Anguwan Kahu people and their representative at the emir's palace.

The ward of Anguwan Liman is located north of the Zaria palace.[citation needed][10]

Transport and economy

[edit]Zaria's economy is primarily based on agriculture. Staples are guinea corn and millet. Cash crops include cotton, groundnuts and tobacco.[3] Not only is Zaria a market town for the surrounding area, it is the home of artisans from traditional crafts like leather work, dyeing and cap making, to tinkers, printshops and furniture makers.[8] Zaria is also the center of a textile industry that for over 200 years has made elaborately hand-embroidered robes that are worn by men throughout Nigeria and West Africa.[11]

Because Zaria is north of the rail junction at Kaduna, it has equal rail access to the seaports at Lagos and Port Harcourt. However, only the railway between Lagos and Kano is functional, as the eastern line of Nigeria's rail network is not operational. This means that Zaria currently has rail access to Lagos and Kano to the north but not Port Harcourt.[12][13]

From 1914 to 1927, Zaria was the break-of-gauge junction station for the Bauchi Light Railway to the tin mines at Jos.[14]

Education

[edit]

Zaria is home to Ahmadu Bello University, the largest university in Nigeria and the second largest on the African continent. The institution is very prominent in the fields of Agriculture, Science, Finance, Medicine and Law.[15] The school is known for the large number of elites from the region that passed through its academic buildings and counts among its alumni five who were Nigerian heads of state, including the late president Umaru Musa Yar'Adua.[16]

Zaria is also the base for the Nigerian College of Aviation Technology,[17] National Research Institute for Chemical Technology,[18] Nigerian Army Depot,[19] Nigerian Military school, Bassawa Baracks, Federal college of Education Zaria.[20] Some historic secondary schools in the adjoining town of Wusasa, where the former Head of the Federal Military Government Yakubu Gowon resides are the St. Bartholomew's School and Science School Kufena, formerly known as St. Paul's College, also MAISS-GIWA a school established by The Emir of Zazzau Dr. Shehu Idris is situated there. Barewa College (formerly Katsina middle school) and Alhudahuda college are other famous secondary schools in the city.[21]

Traditional festivals

[edit]

Zaria is among the northern cities that celebrates the annual cultural durbar festivals in Nigeria.[2] The festival is celebrated twice a year which marks the end of Ramadan and also coinciedes the Muslim festivals of eid al adha and eid al fitri respectively.[11] In Zaria the festival is celebrated in phases. The first day, known as Hawan sallah, consists of the eid prayers and the subsequent tour by the emir around the city from the eid ground to his palace in the company of District heads and the royal guards, while the second day known as Hawan Bariki sallah and so the third day known as Hawan Daushe is the for the last tour by the Emir around the city for the festival.[7][12]

Climate

[edit]Zaria has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen climate classification Aw) with warm weather year-round, a wet season lasting from April to September, and a drier season from October to March.[22]

| Climate data for Zaria (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 38 (100) |

39.5 (103.1) |

40.2 (104.4) |

41 (106) |

40 (104) |

38 (100) |

34 (93) |

32.8 (91.0) |

34 (93) |

35.4 (95.7) |

37 (99) |

36 (97) |

41.0 (105.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 29.8 (85.6) |

32.8 (91.0) |

36.0 (96.8) |

36.6 (97.9) |

34.0 (93.2) |

31.2 (88.2) |

29.3 (84.7) |

28.5 (83.3) |

30.1 (86.2) |

31.7 (89.1) |

32.2 (90.0) |

30.2 (86.4) |

31.9 (89.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 22.2 (72.0) |

25.1 (77.2) |

28.6 (83.5) |

30.0 (86.0) |

28.4 (83.1) |

26.4 (79.5) |

25.1 (77.2) |

24.5 (76.1) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.9 (78.6) |

24.6 (76.3) |

22.5 (72.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 14.6 (58.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

21.2 (70.2) |

23.4 (74.1) |

22.7 (72.9) |

21.5 (70.7) |

20.8 (69.4) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.1 (68.2) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.8 (58.6) |

19.6 (67.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 9 (48) |

11 (52) |

15 (59) |

14 (57) |

16 (61) |

17.5 (63.5) |

16 (61) |

17.8 (64.0) |

18 (64) |

14 (57) |

12 (54) |

8.8 (47.8) |

8.8 (47.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.01) |

5.6 (0.22) |

32.7 (1.29) |

121.9 (4.80) |

147.9 (5.82) |

232.1 (9.14) |

301.9 (11.89) |

208.0 (8.19) |

66.4 (2.61) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1,116.7 (43.96) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 2.9 | 8.4 | 10.6 | 13.5 | 16.6 | 13.9 | 4.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 71.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 37.2 | 31.1 | 32.7 | 51.3 | 69.2 | 77.6 | 82.4 | 85.8 | 83.6 | 73.4 | 53.1 | 44.9 | 60.2 |

| Source: NOAA[23] | |||||||||||||

Environment

[edit]Air quality

[edit]A 2019 study of air pollution in Zaria found that pollution concentrations were within the expected national standards for air pollution.[24]

Land use

[edit]

Zaria's geography and previous land use meant that much of the city's historical land cover was barren.[25] A 2020 study found that barren land decreased from 1990 to 2020 while built environment increased 66 percent and vegetative land increased by 29%.[25] Vegetation had been decreasing from 1990 to 2005, but the study area found a dramatic increase due to agriculture and reforestation afterwards.[25] Predictive modeling based on local policy and urban development trends suggested that increase in urban and vegetative land cover would continue through 2050.[25]

Water supply and sanitation

[edit]

Water provided to the city comes from Kaduna State Water Board.[26] As of 2012, the city of Zaria had 30% access to clean water supply.[26] The African Development Fund issued funding for an expansion project in 2013 for 100 million dollars of $480 million.[26][27] The project had problems with some of its local contractors, resulting in the African Development Bank banning four companies from further participating in bank funding projects.[28] As of August 2020, 60% of water in the system was unaccounted for because of illegal connections, poor metering practices, and poor maintenance.[28]

Notable people

[edit]- Ango Abdullahi is the former Vice Chancellor of Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria

- Shola Ameobi, football player

- Bashir Abubakar, retired Nigerian custom officer, politician Businessman

- Yusuf Datti Baba-Ahmed, Vice Presidential candidate of the Labour Party in 2023 general elections, Senator for Kaduna North from 2011 to 2012 and member of the House of Representatives from 2003 to 2007

- Tajudeen Abbas, speaker of the 10th House of representatives of the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

- Ahmed Nuhu Bamalli, current emir of Zazzau. He was former ambassador of Nigeria to Thailand with concurrent accreditation with Myanmar.

- Nuhu Bamalli, minister of foreign affairs in the first republic, author, state commissioner, former businessman. The state polytechnic is named after him.

- D'banj, musician/Artist

- Umaru Dikko, minister in the second republic

- Edoheart, musician, poet, dancer

- Abubakar Imam, author and novelist

- Shehu Ladan, lawyer, philanthropist and former GMD of Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC)

- Rilwanu Lukman, engineer and former Secretary General of OPEC

- Rumun Ndur, first Nigerian hockey player in the NHL

- Josephine Obiajulu Odumakin, women's rights activist

- Adewale Olukoju, athlete

- Namadi Sambo, former Vice President of Nigeria

- Joshua Selman, gospel minister and televangelist. He is the founder and senior pastor of the Eternity Network International – a Gospel fellowship

- Masai Ujiri, President of the Toronto Raptors of the NBA and first international winner of the NBA Executive of the Year award

- Mukhtar Ramalan Yero, former Governor of Kaduna State.

- Sheikh Albaniy Zaria, Islamic cleric, founder, Darul Hadith Assalafiyya Zaria Nigeria

- Sheikh Ibrahim Zakzaky, Shia Islamic cleric, founder, Islamic Movement in Nigeria

- Zainab Ahmed, former minister of budget and national planning

Gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Zaria population". World Population Review. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Zaria Population 2021 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs)". worldpopulationreview.com. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ a b c "The Britannica Encyclopedia". Retrieved 4 February 2007.

- ^ a b "Zaria | Nigeria". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ "Zaria Town in Kaduna Nigeria Guide". www.nigeriagalleria.com. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ Le Monde, 13 March 2015

- ^ a b "Mass graves for '300 Shia Nigerians' in Zaria". BBC News. 23 December 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ a b c Gihring, Thomas (1984). "Intraurban Activity Patterns among Entrepreneurs in a West African Setting". Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography. 66 (1): 19–20. doi:10.2307/490525. JSTOR 490525.

- ^ "Welcome to Zaria" Archived 27 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine Biotechnology Society of Nigeria (BSN) at Ahmadu Bello University

- ^ Usman, Suleiman (2007). History of Birnin Zaria from 1350 -2902. Zaria -Kaduna: Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. p. 280.

- ^ a b Maiwada, Salihu and Renne, Elisha P. (2007) "New Technologies of Embroidered Robe Production and Changing Gender Roles in Zaria, Nigeria, 1950–2005" Textile History 38(1): pp. 25-58, page 25

- ^ a b "Can Nigeria's renovated railway unite north and south?". BBC News. 13 February 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ "Trains in Nigeria: A slow but steady new chug". The Economist. 9 February 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ Luscombe, Stephen. "The Bauchi Light". www.britishempire.co.uk. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ "History | Ahmadu Bello University". www.abu.edu.ng. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ "Biography: The life and times of Umaru Musa Yar' Adua". Plus TV Africa. 5 May 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "About Us". Nigerian College of Aviation Technology. Archived from the original on April 6, 2010. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ "National Research Institute for Chemical Technology (NARICT, Nigerian Institute of Transport Technology (NITT), National Research Institute for Chemical Technology): About Us". Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2010.

- ^ vanguard (7 October 2017). "Photos: Nigerian Army recruits in training at Depot in Zaria". Vanguard News. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ "About Us – Federal College Of Education, Zaria". Archived from the original on 4 January 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ Mohd, Abubakar Sadiq (20 August 2022). "After 101 years, new challenges stare Barewa College in the face". Daily Trust. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ Hotels.ng. "Ahmadu Bello University | Hotels.ng". Hotels.ng. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991-2020 — Zaria". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ Nimyel, S. H.; Namadi, M. M. (11 September 2019). "Determination of selected air quality parameters in Zaria and its environs, Kaduna State, Nigeria". Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management. 23 (8): 1505–1510. doi:10.4314/jasem.v23i8.14. ISSN 2659-1502.

- ^ a b c d Koko, Auwalu Faisal; Yue, Wu; Abubakar, Ghali Abdullahi; Hamed, Roknisadeh; Alabsi, Akram Ahmed Noman (January 2020). "Monitoring and Predicting Spatio-Temporal Land Use/Land Cover Changes in Zaria City, Nigeria, through an Integrated Cellular Automata and Markov Chain Model (CA-Markov)". Sustainability. 12 (24) 10452. Bibcode:2020Sust...1210452K. doi:10.3390/su122410452.

- ^ a b c "Nigeria - Zaria Water Supply Expansion and Sanitation Project". projectsportal.afdb.org. Archived from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ "AfDB-Assisted Zaria Water Supply, Expansion and Sanitation Project Launched - Nigeria". ReliefWeb. 22 November 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ a b Bungane, Babalwa (21 August 2020). "AfDB bans four companies for fraud in Zaria Water Supply Expansion". ESI-Africa.com. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Smith, Michael G. (1960) Government in Zazzau 1800–1950 International African Institute by the Oxford University Press, London, OCLC 293592; reprinted in 1964 and 1970.

- Dan Isaacs (28 September 2010). "Nigeria's emirs: Power behind the throne". BBC News. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

External links

[edit]Zaria

View on GrokipediaHistory

Founding and Early Hausa Kingdom

Zazzau, later known as Zaria, emerged as one of the seven original Hausa Bakwai city-states around the 11th century, developing from earlier settlements in northern Nigeria's savanna region as a hub for trans-Saharan trade routes involving camel caravans, salt, and leather goods.[6] Archaeological evidence from broader Hausa areas indicates gradual state formation beginning in the 12th century, marked by fortified city walls and ironworking technologies that supported agricultural surplus and military organization, though site-specific excavations at Zazzau remain limited.[7] Traditional oral histories, preserved in Hausa chronicles and later transcribed by 19th-century Fulani scholars like Muhammed Bello, trace Zazzau's origins to mythical migrations linked to the Bayajidda legend, positing a lineage of rulers from the 11th century onward, but these accounts blend folklore with historical kernels and lack corroboration from pre-Islamic inscriptions or artifacts.[8] Empirical records emphasize Zazzau's role in regional alliances and conflicts among Hausa states, with its territory encompassing fertile plains suitable for millet cultivation and cattle herding, fostering a centralized kingship (sarki) system by the 13th-14th centuries.[9] The kingdom's early expansion is associated with rulers like Bakwa Turunku, credited in oral traditions with establishing a more defined capital around the 15th-16th centuries, though dates vary due to reliance on unverified genealogies.[10] Her daughter, Amina (also Aminatu), traditionally ruled circa 1576-1610, leading military campaigns that extended Zazzau's influence southward, fortifying towns with earthen walls and enhancing trade in kola nuts, slaves, and horses; while her existence is affirmed in multiple Hausa sources, specifics of conquests derive from post-hoc narratives with potential embellishments, supported indirectly by evidence of expanded Hausa commercial networks during this era.[2][11] Prior to the 19th-century Fulani jihad, Zazzau maintained autonomy under Hausa dynasties, balancing tribute to Kanem-Bornu and internal clan rivalries.[12]Fulani Jihad and Establishment of the Emirate

The Fulani Jihad, initiated by the scholar Usman dan Fodio in 1804 against the Hausa kingdoms for perceived moral corruption, heavy taxation, and dilution of Islamic practices, expanded rapidly across northern Nigeria.[13] Zazzau, a prominent Hausa state centered in what is now Zaria, resisted but faced mounting pressure as Fulani forces, motivated by religious reform and pastoral interests, overran neighboring territories like Gobir and Katsina.[14] In December 1808, Fulani warriors under the command of Malam Musa captured Birnin Zazzau, the kingdom's capital, defeating the Hausa forces led by Queen Amina descendants and forcing the last Hausa ruler, Makau, to flee southward and establish a successor state at Abuja.[15] This conquest marked the end of indigenous Hausa dynastic rule in Zazzau, with the Fulani imposing a new administrative order aligned with Usman dan Fodio's vision of purified Islamic governance under Sharia law.[9] Malam Musa was appointed as the first emir of Zazzau, ruling from 1808 to 1821, directly subordinating the territory to the emerging Sokoto Caliphate founded by Usman dan Fodio in 1809.[9] The emirate system centralized authority, replacing decentralized Hausa chieftaincies with emir-appointed district heads (ma'ajamai) responsible for tax collection, judicial enforcement of Islamic codes, and military levies to support Sokoto's expansion.[16] This restructuring facilitated stricter adherence to orthodox Islam, curtailed pre-jihad syncretic rituals, and integrated Fulani pastoralists into the ruling class, though it perpetuated ethnic stratification with Fulani emirs dominating over Hausa subjects.[17] The establishment solidified Zazzau's role within the Sokoto Caliphate's feudal network, contributing tribute and troops—estimated at thousands of cavalry—in subsequent campaigns, while local resistance from displaced Hausa elites persisted intermittently until British intervention in 1901.[14] Usman dan Fodio's writings, such as those emphasizing jihad as a means to eradicate tyranny and restore caliphal ideals, justified the overhaul, though implementation involved enslavement of non-combatants and resource extraction that strained rural economies.[18]Colonial Period and British Rule

The British conquest of Zaria occurred in late 1902 as part of the broader pacification of the Sokoto Caliphate, with the city falling with minimal resistance compared to other emirates like Kano and Sokoto.[19] The reigning Emir Kwasau, who had ruled since 1897, was deposed by British forces under Frederick Lugard, reflecting the emirate's weakened position following internal conflicts and external pressures within the caliphate.[20] In early 1903, the British installed Aliyu Dan Sidi (also known as Alu Dan Sidi) as the new emir, marking the transition to colonial oversight while retaining the emirate's hierarchical structure to facilitate administration.[21] [22] Under the policy of indirect rule pioneered by Lugard, the Zaria Emirate was administered through existing native authorities, with the emir and district heads serving as intermediaries for tax collection, judicial functions, and law enforcement, thereby minimizing direct British personnel needs in the Northern Nigeria Protectorate.[1] [23] This system preserved Islamic legal practices in personal matters but subordinated them to colonial oversight, particularly in curtailing slave raiding and inter-emirate warfare that had previously sustained the region's economy.[24] The British reorganized Zaria into districts, stripping the emirate of many vassal territories to centralize control and integrate it into provincial governance, which reduced the emir's autonomous military and expansionist powers.[23] During this era, economic changes included the gradual suppression of domestic slavery through ordinances like the 1901 Slave Trade Proclamation, though enforcement was inconsistent and relied on emirate officials, leading to persistent informal servitude.[25] Infrastructure developments, such as the extension of the Lagos-Kano railway to Zaria by 1911, enhanced trade in groundnuts and cotton, aligning local agriculture with colonial export demands while introducing cash taxes that strained peasant farmers.[26] Resistance was sporadic, often manifesting in tax revolts or evasion rather than open rebellion, as the indirect rule framework co-opted traditional elites, fostering a pragmatic accommodation that endured until Nigeria's independence in 1960.[27]Post-Independence Era and Modern Developments

Following Nigeria's attainment of independence on October 1, 1960, Zaria retained its status as a pivotal center within the Northern Region, later reorganized into states including Kaduna State in 1987.[28] The Zazzau Emirate's traditional governance persisted under the republican framework, balancing customary authority with elected local administration.[1] The establishment of Ahmadu Bello University on October 4, 1962, as the University of Northern Nigeria marked a cornerstone of post-independence development in Zaria.[3] Renamed after the premier of the Northern Region, the institution expanded rapidly to become Nigeria's largest university by enrollment, fostering advancements in agriculture, medicine, and engineering that supported northern Nigeria's human capital growth.[29] By 2024, it ranked as the top public university in Nigeria per Times Higher Education's Sub-Saharan Africa rankings, underscoring its enduring research and educational influence.[30] The emirate's leadership evolved with state oversight; in October 2020, the Kaduna State Government appointed Ambassador Ahmed Nuhu Bamalli, from the Mallawa dynasty, as the 19th Emir, emphasizing continuity amid occasional disputes over succession.[31] Infrastructure enhancements have driven modern progress, including road networks like the Magajiya Junction to Kasuwan Amaru route unveiled in March 2025 to improve connectivity.[32] Federal initiatives allocated N80 billion in 2024 for constructing institutions such as the Federal College of Nursing and Midwifery in Zaria, aiming to bolster healthcare training and local employment.[33] Zaria's economy relies on agriculture, small-scale manufacturing, and services, augmented by the university's ecosystem and Kaduna's industrial corridor, though rural transformation projects in 2025 target agricultural productivity and livelihoods.[34] Religious tensions have periodically disrupted stability, notably the 1987 riots originating in Kafanchan that engulfed Zaria, leading to arson at Ahmadu Bello University's chapel and broader communal clashes between Muslims and Christians.[35] Such events highlight ongoing challenges in managing ethno-religious diversity within the city's Hausa-Fulani dominated society.Geography and Environment

Location, Topography, and Cityscape

Zaria is located in Kaduna State, north-central Nigeria, at geographic coordinates approximately 11°05′N 7°43′E.[36][37] The city serves as a major urban center in the Zazzau Emirate, positioned within the Guinea savanna zone of the country.[38] The topography of Zaria consists of a high plateau with an average elevation of 655 meters above sea level, featuring gently rolling terrain and shallow valleys.[39] Elevations in the area range from about 600 to 700 meters, contributing to its savanna landscape suitable for agriculture and settlement.[40][41] Isolated hills and rock outcrops are present, influencing local soil variation and water flow patterns.[42] Zaria's cityscape reflects a juxtaposition of traditional Hausa architecture and modern developments. The historic core is characterized by mud-brick compounds, defensive walls, and the Emir's palace, embodying feudal city-state layouts with encircling fortifications.[43] In contrast, peripheral areas feature contemporary multi-story buildings, particularly around educational institutions like Ahmadu Bello University, alongside clay huts and institutional structures that define the urban expanse.[44] This architectural diversity arises from the city's evolution from ancient settlements to a modern educational hub.[45]Climate Patterns

Zaria features a tropical savanna climate classified as Aw under the Köppen system, marked by a pronounced wet season and extended dry period with high seasonal temperature variations.[46][47] The wet season occurs from approximately May to October, peaking in August with an average of 27.1 days of measurable precipitation (at least 1 mm), driven by the Intertropical Convergence Zone's northward migration.[48] Annual rainfall totals around 1,000–1,100 mm, concentrated in this period, while the dry season from November to April features negligible precipitation, exacerbated by harmattan winds carrying dust from the Sahara, reducing visibility and humidity to lows of 20–30%.[49] Temperatures remain elevated year-round, with average highs ranging from 30°C (86°F) in the wet season to 35°C (95°F) in April, the hottest month, and lows dipping to 13–15°C (56–59°F) during December–January nights under clear skies.[48][50] Relative humidity peaks above 70% in the wet months but falls below 40% in the dry season, contributing to diurnal ranges of 10–15°C.[46] Historical trends from 1971–2016 data show a statistically significant warming pattern, with mean annual temperatures rising at rates of 0.02–0.04°C per decade in Zaria and surrounding Kaduna areas, alongside a declining rainfall trend of 5–10 mm per year, increasing drought frequency and intensity.[51][52] These shifts align with broader Sahelian variability but are attributed primarily to regional anthropogenic influences and natural oscillations like the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, per analyses of station records from the Nigerian Meteorological Agency.[53] Such patterns have implications for agriculture, with shortened wet seasons reducing crop yields for staples like millet and sorghum.[54]Environmental Challenges and Resource Management

Zaria, situated in Nigeria's semi-arid Sudan Savanna zone, contends with advancing desertification driven by deforestation, overgrazing, and climate variability, which exacerbate soil erosion and reduce arable land availability.[55] [56] Local studies indicate that these processes have intensified land degradation, with indigenous farmers perceiving desertification as a primary threat to agricultural productivity through loss of vegetation cover and biodiversity.[56] Resource management efforts, such as afforestation initiatives, have been implemented but face limitations from ongoing timber harvesting and land conversion for farming, contributing to a net loss in forest cover.[55] Water scarcity and pollution represent acute challenges, particularly in peri-urban areas like Samaru, where approximately 70% of rural households experience shortages of clean potable water, relying heavily on boreholes that often yield contaminated supplies.[57] The Kubanni Reservoir, a key surface water source for Zaria, suffers from microplastic contamination in fish species, stemming from agricultural runoff, domestic sewage, and urban waste, posing risks to human health through bioaccumulation in the food chain.[58] Broader mismanagement, including inadequate treatment of industrial and agrochemical effluents, has degraded groundwater and surface water quality across Kaduna State, amplifying scarcity during dry seasons when rainfall deficits—perceived by 50% of Zaria residents as involving late onset and early cessation—intensify demand pressures.[59] [60] Municipal solid waste (MSW) management strains urban infrastructure in Zaria's high-density zones, where improper disposal practices lead to open dumping and environmental pollution, affecting air quality and leachate infiltration into water bodies.[61] Surveys of 760 households in Zaria and nearby Kaduna Metropolis highlight challenges such as insufficient collection services and lack of recycling facilities, resulting in health risks from vector-borne diseases and soil contamination.[61] Efforts to address these through local government policies remain hampered by resource constraints and enforcement gaps, underscoring the need for integrated strategies combining community participation and technological interventions to mitigate ecological degradation.[61]Demographics and Society

Population Dynamics and Ethnic Composition

The estimated metropolitan population of Zaria reached 766,000 in 2023, reflecting a 2.27% increase from the previous year driven by high fertility rates and rural-to-urban migration patterns common in northern Nigeria.[62] Projections indicate continued growth to 786,000 in 2024 and approximately 810,000 by 2025, at an average annual rate of around 2.6%, aligning with broader demographic trends in Kaduna State where natural population increase predominates amid limited formal census updates since Nigeria's 2006 national census.[62] [63] This expansion has strained urban infrastructure, with the Zaria Local Government Area alone projecting 601,300 residents in 2022 based on National Population Commission extrapolations from 2006 data showing 406,990 inhabitants.[64] Ethnically, Zaria's population is predominantly Hausa-Fulani, forming the core indigenous and ruling groups historically tied to the Zazzau Emirate's Fulani jihad legacy and Hausa city-state traditions.[65] Smaller migrant communities, including Yoruba, Nupe, and Gwari, contribute to diversity, often as Islamic scholars, traders, or students drawn to institutions like Ahmadu Bello University, though they remain minorities without altering the Hausa-Fulani majority dynamic.[65] Exact proportional breakdowns are unavailable due to Nigeria's census emphasis on administrative rather than ethnic granularity, but regional patterns in Kaduna State confirm Hausa-Fulani dominance exceeding 80% in similar northern urban centers, with tensions occasionally arising from southern migrant influxes amid economic opportunities.[66] Population dynamics exhibit a youthful skew, with Nigeria's northern fertility rates averaging 6-7 children per woman fueling organic growth, supplemented by inflows from surrounding rural areas for agricultural trade and education, though outflows occur due to insecurity in peripheral regions.[67] Gender ratios approximate 51.8% male to 48.2% female in recent local estimates, reflecting patrilineal Hausa-Fulani social structures that influence settlement patterns and labor participation.[68]Religious Demographics and Social Structure

Zaria's population adheres predominantly to Islam, consistent with the religious landscape of northern Nigeria where Muslim communities form the majority in urban centers like Zaria.[69] This dominance stems from the historical spread of Islam through trade and the Fulani Jihad of the early 19th century, which established Islamic emirates including Zazzau. A Christian minority persists, primarily comprising southern Nigerian migrants, indigenous converts, and students affiliated with institutions such as Ahmadu Bello University, though exact proportions remain undocumented in official censuses due to the absence of religion-specific data collection.[70] Traces of indigenous traditional beliefs survive among some rural Hausa communities but constitute a negligible fraction amid pervasive Islamic influence.[71] The social structure of Zaria is deeply intertwined with Islamic traditions and the emirate system, featuring a hierarchical organization that privileges religious and noble lineages. At the apex sits the Emir of Zazzau, a hereditary Fulani-descended figure who embodies spiritual and temporal authority, advising on matters of Sharia law and customary governance.[72] This structure reflects post-Jihad stratification, where Fulani elites oversee a predominantly Hausa populace, with social mobility often tied to adherence to Islamic norms and service in traditional roles. Family clans (kabile) and extended kinship networks form the basic units, enforcing patrilineal inheritance and communal obligations reinforced by Quranic principles.[1] Administrative layers beneath the Emir include a council of titled chiefs (alkalai and sarautu holders) and district heads (hakimai), who manage local disputes and resource allocation across the emirate's 32 districts, a division formalized during colonial indirect rule but rooted in pre-colonial Hausa-Fulani organization.[23] Social etiquette and prestige are codified in elaborate protocols of deference, dress, and titles, distinguishing nobles, scholars (mallamai), artisans, and commoners, while gender roles align with conservative Islamic interpretations, limiting women's public leadership though historical queens like Amina challenged such norms. Economic disparities persist, with rural farmers and urban traders forming the base, yet communal solidarity via mosques and markets mitigates fragmentation. Interfaith tensions occasionally arise, as seen in clashes between Sunni majorities and Shia minorities, underscoring religion's role in social cohesion and conflict.[70]Governance and Administration

Traditional Zazzau Emirate Structure

The Zazzau Emirate maintained a centralized hierarchical governance system, dominated by the Emir as the autocratic head who exercised political, judicial, military, and spiritual authority under the overarching suzerainty of the Sokoto Caliphate following the Fulani Jihad of 1804–1808. The Emir appointed officials, enforced Sharia law, collected taxes such as kharaj (land tax) and jangali (cattle tax), and led military campaigns while paying annual tribute to Sokoto, including slaves and military support. Succession involved nomination by an electoral council from four principal royal dynasties—Mallawa, Barebari, Katsinawa, and another—and required approval from the Sultan of Sokoto to prevent dynastic monopolization.[73][74][75] Advising the Emir was a Council of State composed of senior titled nobles, religious scholars (mallams), and officials who balanced his power through consultation on policy, justice, and appointments, though the Emir retained veto authority. The council included key figures such as the Waziri as chief administrative advisor and Sokoto intermediary, the Galadima managing civil affairs and the capital, the Madaki as army commander, the Alkali handling serious judicial cases, and the Limamin Juma’a overseeing religious matters. These roles, often held by royals or loyal freemen, formed the electoral body for selecting successors and met in the palace council chamber to deliberate state affairs.[74][75] The emirate divided into approximately 17–32 districts or fiefs, each administered by a Hakimi appointed by the Emir to supervise taxation, local justice, security, and tribute collection from vassal territories like Keffi and Jema’a. Hakimi reported directly to the Emir or through titled overseers, using intermediaries (jekada) to manage subordinate village and ward heads who handled grassroots enforcement of laws and communal labor. Titled officials received fiefs as remuneration, retaining fixed portions of revenues, which incentivized loyalty amid non-hereditary appointments prone to intrigue and rivalry.[74][75]| Title | Primary Role |

|---|---|

| Waziri | Chief advisor, administration, Sokoto liaison |

| Madaki | Military commander-in-chief |

| Galadima | Deputy ruler, capital and civil administration |

| Alkali | Chief judge for major cases |

| Ma'aji | Treasurer and financial oversight |

| Sarkin Fada | Palace household chief |