Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Gyeongsang Province

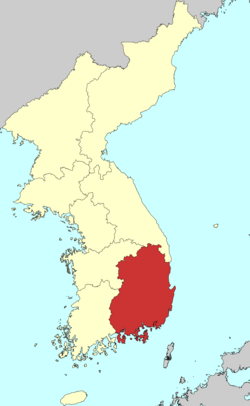

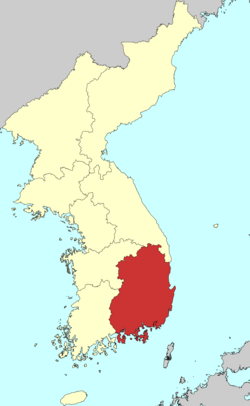

View on WikipediaGyeongsang Province (Korean: 경상도; Hanja: 慶尙道; Korean pronunciation: [kjʌ̹ŋ.sa̠ŋ.do̞]) was one of the Eight Provinces of Joseon Korea. Gyeongsang was located in southeastern Korea.

Key Information

The provincial capital of Gyeongsang was Daegu. The region was the birthplace of the kingdom of Silla, which unified Korea in 668 CE. The region also has a highly significant role in modern Korean history; every non-acting South Korean president from 1963 to 2022 except Choi Kyu-hah (1979-1980) had ancestry from Gyeongsang, and all except Lee Myung-bak were also born in Gyeongsang.

Today, the historical region is divided into five administrative divisions: the three independent cities of Busan, Daegu and Ulsan, and the two provinces of North Gyeongsang Province and South Gyeongsang Province. The largest city in the historical region is Busan, followed by Daegu.

History

[edit]The predecessor to Gyeongsang Province was formed during the Goryeo (918-1392), replacing the former provinces of Yeongnam, Sannam and Yeongdong.

Gyeongsang acquired its current name in 1314. The name derives from names of the principal cities of Gyeongju and Sangju.

In 1895, Gyeongsang was replaced by the districts of Andong in the north, Daegu (대구부; 大邱) in the centre, Jinju in the southwest, and Dongnae (동래부; 東萊府; now Busan) in the southeast.

In 1896, Andong, Daegu, and northern Dongnae Districts were merged to form North Gyeongsang, and Jinju and southern Dongnae districts were merged to form South Gyeongsang. North and South Gyeongsang are part of South Korea today.

Language

[edit]The language used in Gyeongsang province (south and north) is the Yeongnam dialect of Korean, also called the Gyeongsang dialect, and the intonation and vocabulary is different from the standard Seoul dialect (표준어, pyojuneo) in several ways.[1] Yeongnam dialect itself is further subdivided into several dialects. For example, Busan dialect is slightly different from Andong dialect and Uljin dialect.

| English | Seoul dialect | Gyeongsang dialect |

|---|---|---|

| key | 열쇠 yeolsoe | 쇳대 soetdae (in Busan) |

| whole, every, all | 모두 modu, 언제나 eonjena, 항시 hangsi | 마카 maka (in Yaecheon county) |

| Why do you do that? (asking reason of an action-sentence) | 왜 그래요? Wae geuraeyo?, 왜 그러세요? Wae geureoseyo? | 와 그랑교? Wa geuranggyo? (in Southern Gyeongsang, Busan, Ulsan) 와 그리니껴? Wa geurinikkyeo? (in Northern Gyeongsang) |

Geography

[edit]Gyeongsang Province was bounded on the west by Jeolla and Chungcheong Provinces, on the north by Gangwon Province, on the south by Korea Strait, and on the east by the Sea of Japan. The region is ringed by the Taebaek and Sobaek Mountains and is drained by the Nakdong River.

The largest cities in the region are Busan, Daegu, and Ulsan. Other cities of note are Gyeongju (the former capital of Silla), Andong, Yeongju, Sangju, Gimcheon, Miryang, Gimhae, Changwon (the capital of South Gyeongsang), Masan, and Jinju.[2]

The Gyeongsang region as a whole is often referred to by the regional and former provincial name of "Yeongnam" (The term "Yeongdong" is applied today to Gangwon Province).

References

[edit]- ^ Long, D & Yim, Y.-C. (2002). ''Regional differences in the perception of Korean dialects''. In D. Long & D. Preston (eds.). ''Handbook of Perceptual Dialectology Volume II'', pp. 249-275.

- ^ Jang, Seok-Gil Denver; Lee, Juhyun; Gim, Tae-Hyoung Tommy (2024-05-06). "Smart adaptation to urban shrinkage in North Gyeongsang province, South Korea: opportunities and obstacles for implementation". Urban Research & Practice: 1–25. doi:10.1080/17535069.2024.2350462. ISSN 1753-5069.