Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lagash

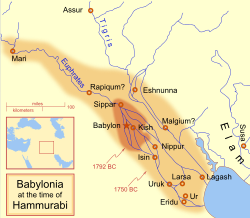

View on WikipediaLagash[4] (/ˈleɪɡæʃ/; cuneiform: 𒉢𒁓𒆷𒆠 LAGAŠKI; Sumerian: Lagaš) was an ancient city-state located northwest of the junction of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and east of Uruk, about 22 kilometres (14 mi) east of the modern town of Al-Shatrah, Iraq. Lagash (modern Al-Hiba in Dhi Qar Governorate) was one of the oldest cities of the Ancient Near East, and the Lagash state incorporated the cities of Lagash, Girsu, Nina.[5] Girsu (modern Telloh), about 25 km (16 mi) northwest of Lagash, was the religious center of the Lagash state, with its main temple, the E-ninnu, dedicated to the god Ningirsu. The ancient site of Nina (Tell Zurghul), around 10 km (6.2 mi) away, marks the southern limit of the state.

Key Information

History

[edit]Though some Uruk period pottery shards were found in a surface survey, significant occupation at the site of Lagash began early in the 3rd Millennium BC, in the Early Dynastic I period (c. 2900–2600 BC). Surface surveys and excavations show that the peak occupation, with an area of about 500 hectares occurred during the Early Dynastic III period (c. 2500–2334 BC). The later corresponds with what is now called the First Dynasty of Lagash.[6] Lagash then came under the control of the Akkadian Empire for several centuries. With the fall of that empire, Lagash had a period of revival as an independent power during the 2nd Dynasty of Lagash before coming under the control of the 3rd Dynasty of Ur. After the fall of Ur, there was some modest occupation in the Isin-Larsa and Old Babylonian periods.[7] Lagash was then largely deserted until a Seleucid era fortress was built there in the 2nd century BC.[8]

First dynasty of Lagash (c. 2520 – c. 2260 BC)

[edit]

The dynasties of Lagash are not found on the Sumerian King List (SKL) despite being a power in the Early Dynastic period and a major city in the centuries that followed. One tablet, from the later Old Babylonian period and known as The Rulers of Lagash, was described by its translator as "rather fanciful" and is generally considered to be a satirical parody of the SKL. The thirty listed rulers, in the style of the SKL, having improbable reigns, include seven known rulers from the 1st Dynasty of Lagash, including Ur-Nanshe, "Ane-tum", En-entar-zid, Ur-Ningirsu, Ur-Bau, and Gudea.[9][10]

Little is known of the first two rulers of Lagash. En-hegal is believed to be the first ruler of Lagash. A tablet with his name describes a business transaction, in which a possible King En-hegal buys land.[11] Both his status and date are disputed.[12] He was followed by Lugalshaengur about whom also little is known.[13] Mesilim, who called himself King of Kish though it is uncertain which city he was from, named Lugalshaengur as an "ensi" of Lagash on a mace head.[14]

Ur-Nanshe

[edit]While many details like the length of reign are not known for the next ruler, Ur-Nanshe, a number of his inscriptions have been found, most at Lagash with one stele at Ur, which along with Umma, he claimed to have conquered in battle.[15] Almost all deal with the construction of temples, one details how he "built the wester[n] channel at the side of Sa[la]/ channel at the side of S[al] (against) the Amorites". He is described as the "son of Gu-NI.DU" (occasionally as "son of Gur:SAR"), and his inscriptions list a number of sons and daughters.[16] Several inscriptions say "He [had the ships of Dil]mun sub[mit] [timber] (to Lagaš) as tribute." His son Akurgal ruled briefly after him.[17]

Eannatum

[edit]The next ruler, Eannatum (earlier referred to as "Eannadu"), son of Akurgal and grandson of Ur-Nanshe, turned Lagash into a major power extending throughout large areas of Mesopotamia and to the east as well. In an inscription found at ancient Adab:

"Eannatum, ruler of Lagash, granted strength by Enlil, nourished with special milk by Ninhursag, nominated by Ningirsu, chosen in her heart by Nanshe, son of Akurgal ruler of Lagash, defeated mountainous Elam, defeated Urua, defeated Umma, defeated Ur. At that time, he built a well of fired bricks for Ningirsu in his (Ningirsu’s) broad courtyard. His personal god is Shulultul. Then, Ningirsu loved Eannatum."[18]

Another inscription detail his destruction of "Kiš, Akšak, and Mari at a place named Antasur". He also claimed to have taken the city of Akshak and killed its king, Zuzu.[19] Eannatum took the city of Uru'az on the Persian Gulf, and exacted tribute as far as Mari; however, many of the realms he conquered were often in revolt.[20] During his reign, temples and palaces were repaired or erected at Lagash and elsewhere and canals and reservoirs were excavated.[21] During his reign, Dilmun was a major trading partner.[22]

A long running border dispute, dating back at least to the time of Lugalshaengur, existed between the city-states of Umma and Lagash.[23] In the time of Umma ruler Enakalle a formal border was established, mediated by Mesilim, “king of Kish”. Eannatum restored the border, including the boundary markers of Mesilim.

"Eanatum, ruler of Lagash, uncle of Enmetena ruler of Lagash, demarcated the border with Enakalle, ruler of Umma. He extended the [boundary-]channel from the Nun-channel to Guʾedena, leaving a 215-nindan [= 1,290 meters] [strip] of Ningirsu’s land under Umma’s control, establishing a no-man’s land there. He inscribed [and erected] monuments at that [boundary-]channel, and restored the monument of Mesilim, but did not cross into the plain of Umma. "[24]

In c. 2450 BC, Lagash and the neighboring city of Umma fell out with each other after a border dispute over the Guʾedena, a fertile area lying between them. As described in Stele of the Vultures, of which only a portion has been found (7 fragments), the current king of Lagash, Eannatum, inspired by the patron god of his city, Ningirsu, set out with his army to defeat the nearby city.[26] According to the Stele's engravings, when the two sides met each other in the field, Eannatum dismounted from his chariot and proceeded to direct his men on foot. After lowering their spears, the Lagash army advanced upon the army from Umma in a dense phalanx.[27] After a brief clash, Eannatum and his army had gained victory over the army of Umma. This battle is one of the earliest depicted organised battles known to scholars and historians.[28]

Eannatum was succeeded by his brother, En-anna-tum I. Given the many inscriptions his reign is assumed to be of some length. Most of them detailed the usual temple construction. On long tablet described the continued conflict with Umma:

"For the god Hendursag, chief herald of the Abzu En-anatum, [ru]ler of [Laga]š ... When the god Enlil(?)], for the god [Nin]g[ir]s[u], took [Gu'edena] from the hands of Gisa (Umma) and filled En-anatum’s hands with it, Ur-LUM-ma, ruler of Gisa (Umma), [h]i[red] [(mercenaries from) the foreign lands] and transgressed the boun[da]ry-channel of the god Ningirsu (and said): ... En-anatum crushed Ur-LUM-ma, ruler of Gisa (Umma) as far as E-kisura (“Boundary) Channel”) of the god Ninœirsu. He pursued him into the ... of (the town) LUM-ma-girnunta. (En-anatum) gagged (Ur-LUM-ma) (against future land claims)"[14]

The conflict from the Umma side of things from its ruler Ur-Lumma:

"Urlumma, ruler of Umma, diverted water into the boundary-channel of Ningirsu and the boundary-channel of Nan-she. He set fire to their monuments and smashed them, and destroyed the established chapels of the gods that were built on the boundary-levee called Namnunda-kigara. He recruited foreigners and transgressed the boundary-ditch of Ningirsu."[29]

Entemena

[edit]The next ruler, Entemena increased the power of Lagash during his rule. A number of inscriptions from his reign are known.[30][31] He was a contemporary of Lugalkinishedudu of Uruk.[32]

Entemena was succeeded by his brother Enannatum II, with only one known inscription where he "restored for the god Ningirsu his brewery".[14] He was followed by two more minor rulers, Enentarzi (only one inscription from his 5 year reign, which mentions his daughter Gem[e]-Baba), and Lugalanda (several inscriptions, one mentions his wife Bara-namtara) the son of Enentarzi. The last ruler of Lagash, Urukagina, was known for his judicial, social, and economic reforms, and his may well be the first legal code known to have existed.[33][34] He was defeated by Lugalzagesi, beginning when Lugalzagesi was ruler of Umma and culminating as ruler of Uruk, bringing an end to the First Dynasty of Lagash.[35] About 1800 cuneiform tablets from the reigns of the last three rulers of Lagash, of an administrative nature, have been found, mostly.[36][37][38] The tablets are mostly from the "woman’s quarter" also known as the temple of the goddess Babu. It was under the control of the Queen.[39]

-

The cuneiform text states that Enannatum I reminds the gods of his prolific temple achievements in Lagash. Circa 2400 BC. From Girsu, Iraq. The British Museum, London

-

The name "Lagash" (𒉢𒁓𒆷) in vertical cuneiform of the time of Ur-Nanshe.

-

The armies of Lagash led by Eannatum in their conflict against Umma.

-

Lancers of the army of Lagash against Umma

Under the Akkadian Empire

[edit]In his conquest of Sumer circa 2300 BC, Sargon of Akkad, after conquering and destroying Uruk, then conquered Ur and E-Ninmar and "laid waste" the territory from Lagash to the sea, and from there went on to conquer and destroy Umma, and he collected tribute from Mari and Elam. He triumphed over 34 cities in total.[40]

Sargon's son and successor Rimush faced widespread revolts, and had to reconquer the cities of Ur, Umma, Adab, Lagash, Der, and Kazallu from rebellious ensis.[41]

Rimush introduced mass slaughter and large scale destruction of the Sumerian city-states, and maintained meticulous records of his destruction.[41] Most of the major Sumerian cities were destroyed, and Sumerian human losses were enormous: for the cities of Ur and Lagash, he records 8,049 killed, 5,460 "captured and enslaved" and 5,985 "expelled and annihilated".[41][42]

A Victory Stele in several fragments (three in total, Louvre Museum AO 2678)[43] has been attributed to Rimush on stylistic and epigraphical grounds. One of the fragments mentions Akkad and Lagash.[44] It is thought that the stele represents the defeat of Lagash by the troops of Akkad.[45] The stele was excavated in ancient Girsu, one of the main cities of the territory of Lagash.[44]

-

Detail

-

Man of Lagash, circa 2270 BC, from the Victory Stele.[48] The same hairstyle can be seen in other statues from Lagash.[49]

Second dynasty of Lagash (c. 2260 – c. 2023 BC)

[edit]

During the reigns of the first two rulers of this dynasty Lugal-ushumgal (under Naram-Sin and Shar-Kali-Sharri) and Puzur-Mama (under Shar-kali-shari), Lagash was still under the control of the Akkadian Empire. It has been suggested that another governor, Ur-e, fell between them.[50] After the death of Shar-Kali-shari Puzur-Mama declared Lagash independent (known from an inscription that may also mention Elamite ruler Kutik-Inshushinak). This independence appears to have been tenuous as Akkadian Empire ruler Dudu reports taking booty from there.[14]

With the fall of Akkad, Lagash achieved full independence under Ur-Ningirsu I (not to be confused with the later Lagash ruler named Ur-Ningirsu, the son of Gudea). Unlike the 1st Dynasty of Lagash, this series of rulers used year names. Two of Ur-Ningirsu are known including "year: Ur-Ningirsu (became) ruler". His few inscriptions are religious in nature.[51] Almost nothing is known of his son and successor.[52] The next three rulers, Lu-Baba, Lugula, and Kaku are known only from their first year names. The following ruler, Ur-Baba, is notable mainly because three of his daughters married later rulers of Lagash, Gudea, Nam-mahani, and Ur-gar.[53] His inscriptions are all of a religious nature, including building or restoring the "Eninnu, the White Thunderbird".[54] Five of his year names are known. At this point Lagash is still at best a small local power. In some case the absolute order of rulers is not known with complete certainty.[55]

Gudea

[edit]While the Gutians had partially filled the power vacuum left by the fall of the Akkadian Empire, under Gudea Lagash entered a period of independence marked by riches and power.[56] Thousands of inscriptions of various sorts have been found from his reign and an untold number of statues of Gudea.[57] A number of cuneiform tablets of an administrative nature, from Gudea's rule were found at nearby Girsu.[58] Also found at Girsu were the famous Gudea cylinders which contain the longest known text in the Sumerian language.[59][60] He was prolific at temple building and restoring.[61] He is known to have conducted some military operations to the east against Anshan and Elam.[62][63] Twenty of Gudea's year names are known. All are of a religious nature except for one that marks the building of a canal and year six "Year in which the city of Anszan was smitten by weapons".[64] While the conventional view has been that the reign of Gudea fell well before that of Ur-Nammu, ruler of Ur, and during a time of Gutian power, a number of researchers contend that Gudea's rule overlaps with that of Ur-Nammu and the Gutians had already been defeated.[65] This view is strengthened by the fact that Ur-Baba appointed Enanepada as high preiestess of Ur while Naram-Sin of Akkad had appointed her predecessor Enmenana and Ur-Namma of Ur appointed her successor Ennirgalana.[66]

Gudea was succeeded by his son Ur-Ningirsu, followed by Ur-gar. Little is known about either aside from an ascension year name each and a small handful of inscriptions. It has been suggested that two other brief rulers fit into the sequence here, Ur-ayabba and Ur-Mama but the evidence for that is thin.[67] Two tablets dated to the reign of Ur-Nammu of Ur refer to Ur-ayabba as "ensi" of Lagash, meaning governor in Ur III terms and king in Lagash.[66]

Nam-mahani

[edit]Little is known of the next ruler aside from his ascension year name and a handful of religious inscriptions. Nam-mahani is primarily known for being defeated by Ur-Nammu, first ruler of the Ur III empire and being considered the last ruler of the second dynasty of Lagash (often called the Gudean Dynasty). In the prologue of the Code of Ur-Nammu it states "He slew Nam-ha-ni the ensi of Lagash".[68] A number of his inscriptions were defaced and the statues of Nam-mahani and his wife were beheaded (the head were not found with the statues by Ur-Nammu in what is usually called an act of Damnatio memoriae.[57]

Under the Ur III Empire

[edit]Under the control of Ur, the Lagash state (Lagash, Girsu, and Nigin) were the largest and most prosperous province of the empire. Such was its importance that the second highest official in the empire, the Grand Vizier, resided there.[69][70][71][72] The name of one governor of Lagash under Ur is known, Ir-Nanna. After the fifth year of the last Ur III ruler, Ibbi-Sin, his year name was no longer used at Lagash, indicating Ur no longer controlled that city.[73]

Archaeology

[edit]

Lagash is one of the largest archaeological sites in the region, measuring roughly 3.5 kilometers north to south and 1.5 kilometers east to west though is relatively low being only 6 meters above the plain level at maximum. Much of the older area is under the current water table and not available for research. A drone survey posited that Lagash developed on four marsh islands some of which were gated,[74] but the notion that the city was marsh-based is in contention.[75] Estimates of its area range from 400 to 600 hectares (990 to 1,480 acres). The site is divided by the bed of a canal/river, which runs diagonally through the mound. The site was first excavated, for six weeks, by Robert Koldewey in 1887.[76]

"To be sure, the difficulties involved were known, at least after Koldewey’s disaster in el-Hibba where, unprepared to deal with structures of unbaked material, he did not recognize the walls but only those baked bricks which had been used for lining graves, leading him to conclude that el-Hibba was nothing but an extended burial place."[77]

It was inspected during a survey of the area by Thorkild Jacobsen and Fuad Safar in 1953, finding the first evidence of its identification as Lagash.[78] The major polity in the region of al-Hiba and Tello had formerly been identified as ŠIR.BUR.LA (Shirpurla).[79]

Tell Al-Hiba was again explored in five seasons of excavation between 1968 and 1976 by a team from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Institute of Fine Arts of New York University. The team was led by Vaughn E. Crawford, and included Donald P. Hansen and Robert D. Biggs. Twelve archaeological layers were found with the bottom 9 being Early Dynastic and the lowest under the water table. The primary focus was the excavation of the temple Ibgal of Inanna and the temple Bagara of Ningirsu, as well as an associated administrative area.[80][81][82][83] The team returned 12 years later, in 1990, for a sixth and final season of excavation led by D. P. Hansen. The work primarily involved areas adjacent to an, as yet, unexcavated temple Ibgal of the goddess Inanna in the southwest edge of the city. The Bagara temple of Ningirsu was also worked on. Both were built by Early Dynastic III king Eannatum. Temples to the goddesses Gatumdag, Nanshe, and Bau are known to have existed but have not yet been found. A canal linked the E-ninnu temple of Ningirsu at Girsu, the E-sirara temple of Nanshe at Nigin, and the Bagara temple at Lagash, the three cities being part of one large state.[84][85][86] In 1984 a surface survey found that most finds were from the Early Dynastic III period. Small amounts of Uruk, Jemdet Nasr, Isin-Larsa, Old Babylonian and Kassite shards were found in isolated areas.[87]

In March–April 2019, field work resumed as the Lagash Archaeological Project[88] under the directorship of Dr. Holly Pittman of the University of Pennsylvania's Penn Museum in collaboration with the University of Cambridge and Sara Pizzimenti of the University of Pisa. A second season ran from October to November in 2021. A third season ran from March 6 to April 10, 2022.[89] The work primarily involved the Early Dynastic Period Area G and Area H locations along with Geophysical Surveying and Geoarchaeology. The focus was on an industrial area and associated streets, residences, and kilns. Aerial mapping of Lagash, both using UAV drone mapping and satellite imagery was performed.[90] In the fall of 2022 a 4th season of excavation resumed. Among the finds were a public eatery with ovens, a refrigeration system, benches, and large numbers of bowls and beakers.[91][92][93][94]

Archaeological remains

[edit]Area A (Ibgal of Inanna)

[edit]Though commonly known as Area A or the Ibgal of Inanna, this temple complex was actually named Eanna during the Ur periods, while Inanna’s sanctuary within Eanna was known as Ibgal.[95]

Level I architecture

[edit]

Level I of Area A was occupied from Early Dynastic (ED I) to Ur III.[95] It was used for both daily worship activities and festive celebrations, particularly for the queen of Lagash during the Barley and Malt-eating festivals of Nanše.[95][96]

Level I consists of an oval wall on the Northeast end, surrounding an extensive courtyard. The fragments, together comparison to another Sumerian temple at Khafajah, show that the wall should originally be approximately 130m long.[97]

For the temple-building, it is connected to the courtyard with steps. Twenty-five rooms have been excavated inside the building, in which the western ones would open up to the outside of the temple with corridors and form a tripartite entrance.[95] Both the temple-building and the oval wall were built with plano-convex mud bricks, which was a very common material up to the late Early Dynastic III period. Additionally, foundations are found under the temple-building. They are composed of rectangular areas of various sizes, some as solid mud bricks and some as cavities of broken pieces of alluvial mud and layers of sand, then capped again with mud bricks.[97]

Level II and Level III architecture

[edit]Two more levels are present beneath Level I. All of them are similar to each other in terms of layout and construction materials. During the process of building on top of each other, workers at that time would choose to destroy some portions while keeping some others, leading to much open speculation as to the rationales behind.[98]

Area B (3HB Building and 4HB Building at Bagara of Ningirsu)

[edit]The 3HB Building

[edit]Three building levels were discovered and 3HB III is the earliest and most well-preserved level. 3HB II and 3HB I shared the same layout with 3HB III. All three levels have a central niched-and-buttressed building which is surrounded by a low enclosure wall with unknown height.[95]

| Building Level | Building Material[95] | Occupation Period[95] | Notes[95] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3HB III | Plano-convex bricks, mud plaster | ED IIIB

(Eannatum’s rule or later) |

Dimensions:

3HB Building: 24 x 20m Enclosure Wall: approximately 31m x 25m |

| 3HB II | Plano-convex bricks, mud plaster | ED IIIB – Late Akkadian | |

| 3HB I | Plano-convex bricks, mud plaster | Late – Post-Akkadian |

An excavator believes that the 3HB Building was a “kitchen temple” that aimed at meeting some of the god’s demands.[99] Alternatively, it has been suggested that the building was a shrine in the Bagara complex as it shared more similarities with other temples than kitchens in terms of layout, features and contents.[95]

The 4HB Building

[edit]

The excavators discovered five building levels. The layout of 4HB V cannot be obtained due to limited exploration. 4HB IV-4HB I shared the same layout. 4HB IVB was the first level that was exposed completely.[95]

| Building Level | Building Material[95] | Occupation Period[95] | Notes[95] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4HB V | Plano-convex bricks | ED III

(Evidence from pottery) |

|

| 4HB IVA | Plano-convex bricks | ED III

(Evidence from pottery) |

|

| 4HB IVB | Plano-convex bricks | ED IIIB | Dimensions:

4HB Building: 23 x 14m |

| 4HB III | Plano-convex bricks | ED IIIB – Late Akkadian | |

| 4HB II | Plano-convex bricks | Late – Post-Akkadian | |

| 4HB I | Plano-convex bricks

and flat, square bricks |

Gudea’s rule |

It has been suggested that the 4HB Building is a brewery as ovens and storage vats and a tablet mentioning “the brewery” and “a brewer” were found.[99] An alternate proposal is that 4HB building is a kitchen as it shared lots of similarities with temple kitchens at Ur and Nippur.[95]

Area C

[edit]Located 360 meters southeast of Area B. It contains a large Early Dynastic administrative area with two building levels (1A and 1B). In level 1B were found sealing and tablets of Eanatum, Enanatum I, and Enmetena.[100]

Area G

[edit]

Area G is located at the midway of Area B in the North and Area A in the South. First excavated by Dr Donald P. Hansen in season 3H, Area G consists of a building complex and a curving wall which are separated by around 30-40m.[95]

Western Building Complex

[edit]

5 building levels are found in the area. There is little information about Levels I and IIA as they were poorly preserved without sealed floor deposits.[101] In Levels IIB, III and IV, changes can be found in the building complex with reconstructions. In Level III, benches are built near the eastern and northern courtyards. Sealings made in the “piedmont” style which are found in the rooms share a resemblance with the Seal Impression Strata of Ur and sealings from Inanna Temple at Nippur,[101] indicating the administrative nature of the buildings. Apart from institutional objects, fireplaces, bins and pottery were found in the rooms as well.[99]

Curving Wall (Eastern Zone)

[edit]A 2-m wide wall that runs from the south to the north is found on the eastern part of Area G. The features of the curving wall and the rooms found near it are determined to be different from other oval temples built in the Early Dynastic in other major states. Intrusive vertical drains are found at the base of the plano-convex foundation.[99] Archaeologists excavated further deeper to the water level during season 4H and found extensive Early Dynastic I deposits.[95]

List of rulers

[edit]Although the first dynasty of Lagash has become well-known based on mentions in inscriptions contemporaneous with other dynasties from the Early Dynastic (ED) III period; it was not inscribed onto the Sumerian King List (SKL). The first dynasty of Lagash preceded the dynasty of Akkad in a time in which Lagash exercised considerable influence in the region. The following list should not be considered complete:

| Portrait or inscription | Ruler | Approx. date and length of reign | Comments, notes, and references for mentions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Dynastic IIIa period (c. 2600 – c. 2500 BC) | |||

| Predynastic Lagash (c. 2600 – c. 2520 BC) | |||

|

(En-hegal) 𒂗𒃶𒅅 |

reigned c. 2570 BC (MC) |

|

| (Lugalshaengur) 𒈗𒊮𒇉 |

r. c. 2530 BC (MC) |

||

| Portrait or inscription | Ruler | Approx. date and length of reign (MC) | Comments, notes, and references for mentions |

| Early Dynastic IIIb period (c. 2500 – c. 2350 BC) | |||

| First dynasty of Lagash / Lagash I dynasty (c. 2520 – c. 2260 BC) | |||

|

Ur-Nanshe (Ur-nina) 𒌨𒀭𒀏 |

r. c. 2520 BC (MC) |

|

|

Akurgal 𒀀𒆳𒃲 |

r. c. 2500 BC (MC) (9 years) |

|

|

Eannatum 𒂍𒀭𒈾𒁺 |

r. c. 2450 BC (MC) (27 years) |

|

|

Enannatum I 𒂗𒀭𒈾𒁺 |

r. c. 2425 BC (MC) (4 years) |

|

|

Entemena 𒂗𒋼𒈨𒈾 |

r. c. 2420 BC (MC) (27 years) |

|

|

Enannatum II 𒂗𒀭𒈾𒁺 |

r. c. 2400 BC (MC) (5 years) |

|

|

Enentarzi 𒂗𒇷𒋻𒍣 |

r. c. 2400 BC (MC) (5 years) |

|

|

Lugalanda 𒈗𒀭𒁕 |

r. c. 2400 BC (MC) (6 years and 1 month) |

|

| Proto-Imperial period (c. 2350 – c. 2260 BC) | |||

|

Urukagina 𒌷𒅗𒄀𒈾 |

r. c. 2350 BC (MC) (11 years) |

|

| Meszi | Uncertain; these two rulers may have r. c. 2342 – c. 2260 BC sometime during the Proto-Imperial period.[102] |

| |

| Kitushi |

| ||

| Portrait or inscription | Ruler | Approx. date and length of reign | Comments, notes, and references for mentions |

| Akkadian period (c. 2260 – c. 2154 BC) | |||

| Second dynasty of Lagash / Lagash II dynasty (c. 2260 – c. 2023 BC) | |||

| Ki-Ku-Id | r. c. 2260 BC (MC) |

||

| Engilsa | r. c. 2250 BC (MC) |

||

| Ur-A | r. c. 2230 BC (MC) |

||

|

(Lugal-ushumgal) 𒈗𒃲𒁔 |

r. c. 2230 – c. 2210 BC (MC) |

|

| (Puzer-Mama) 𒂗𒃶𒅅 |

Uncertain; these seven rulers may have r. c. 2210 – c. 2164 BC sometime during the Akkadian period. |

| |

| Ur-Ningirsu I[103] 𒌨𒀭𒎏𒄈𒍪 |

|||

| Ur-Mama | |||

| Ur-Utu | |||

| Lu-Baba[103] | |||

| Lugula[103] 𒇽𒄖𒆷 |

|||

| Kaku[103] 𒅗𒆬 |

|||

|

Ur-Baba 𒌨𒀭𒁀𒌑 |

r. c. 2164 – c. 2144 BC (MC) r. c. 2093 – c. 2080 BC |

|

| Gutian period (c. 2154 – c. 2119 BC) | |||

|

Gudea 𒅗𒌤𒀀 |

r. c. 2144 – c. 2124 BC (MC) r. c. 2080 – c. 2060 BC |

|

|

Ur-Ningirsu II 𒌨𒀭𒎏𒄈𒍪 |

r. c. 2124 – c. 2119 BC (MC) r. c. 2060 – c. 2055 BC |

|

| Pirig-me 𒊊𒀞 |

r. c. 2119 – c. 2117 BC (MC) r. c. 2055 – c. 2053 BC |

| |

| Ur-gar 𒌨𒃻 |

r. c. 2117 – c. 2113 BC (MC) r. c. 2053 – c. 2049 BC |

| |

| Ur III period (c. 2119 – c. 2004 BC) | |||

|

Nam-mahani 𒉆𒈤𒉌 |

r. c. 2113 – c. 2110 BC (MC) r. c. 2049 – c. 2046 BC |

|

| Ur-Ninsuna | r. c. 2090 – c. 2080 BC (MC) |

||

| Ur-Nikimara | r. c. 2080 – c. 2070 BC (MC) |

||

| Lu-Kirilaza | r. c. 2070 – c. 2050 BC (MC) |

||

| Ir-Nanna | r. c. 2050 – c. 2023 BC (MC) |

||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "ETCSLsearch". Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ The Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary. "Lagash." Accessed 19 Dec 2010.

- ^ "ePSD: lagaš[storehouse]". Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ [NU11.BUR].LAKI[1] or [ŠIR.BUR].LAKI, "storehouse"[2] Akkadian: Nakamtu;[3]

- ^ Williams, Henry (2018). Ancient Mesopotamia. Ozymandias Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-5312-6292-1.

- ^ McMahon, Augusta, et al., "Dense urbanism and economic multi-centrism at third-millennium BC Lagash", Antiquity, pp. 1-20, 2023

- ^ Westenholz, Joan Goodnick (1984). "Kaku of Ur and Kaku of Lagash". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 43 (4): 339–342. doi:10.1086/373095. ISSN 0022-2968. JSTOR 544849. S2CID 161962784.

- ^ CHH,"Sumerian Diorite Head: Purchased from the Francis Bartlett Donation of 1912", Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts, pp. 30-34, 1927

- ^ Sollberger, Edmond. “The Rulers of Lagaš.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 21, pp. 279–91, 1967

- ^ "The rulers of Lagaš". Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. June 1, 2003 [1998]. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- ^ Barton, George A., "Sumerian Business and Administrative Documents", Philadelphia University, 1915

- ^ a b "Enhegal". CDLI Wiki. January 14, 2010. Retrieved 2020-12-22.

- ^ Maeda, Tohru, "King of Kish" in Pre-Sargonic Sumer", Orient 17, pp. 1-17, 1981

- ^ a b c d Frayne, Douglas R., "Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia: Early Periods", RIME 1.08, 2007

- ^ Romano, Licia, "Urnanshe’s Family and the Evolution of Its Inside Relationships as Shown by Images", La famille dans le Proche-Orient ancien: réalités, symbolismes et images: Proceedings of the 55e Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Paris, edited by Lionel Marti, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 183-192, 2014

- ^ Jacobsen, Thorkild, "Ur-Nanshe’s Diorite Plaque", Orientalia, vol. 54, no. 1/2, pp. 65–72, 1985

- ^ Douglas Frayne, "Lagas", in Presargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700-2350 BC), RIM The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia Volume 1, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 77-293, 2008 ISBN 9780802035868

- ^ Wilson, Karen, "Bismaya: Recovering the Lost City of Adab", Oriental Institute Publications 138, Chicago, Ill, Univ. of Chicago Press, 2012 ISBN 9781885923639

- ^ Curchin, Leonard, "Eannatum and the Kings of Adab", Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale, vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 93–95, 1977

- ^ Steinkeller, Piotr (2018-01-29). "The birth of Elam in history". The Elamite World. Routledge. pp. 177–202. doi:10.4324/9781315658032-11. ISBN 978-1-315-65803-2.

- ^ Vukosavović, Filip, "On Some Early Dynastic Lagaš Temples", Die Welt Des Orients, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 126–30, 2014

- ^ Foster, Benjamin R. and Foster, Karen Polinger, "Early City-States", Civilizations of Ancient Iraq, Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 35-50, 2009

- ^ Hritz, C., "The Umma-Lagash Border Conflict: A View from Above" in Altaweel, M. and Hritz, C. (eds.), From Sherds to Landscapes: Studies on the Ancient Near East in Honor of McGuire Gibson. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, pp. 109–32, 2021

- ^ Jerrold S. Cooper, "Reconstructing History from Ancient Inscriptions:The Lagash-Umma Border Conflict", Sources from the Ancient Near East 2/1; Malibu, CA: Undena, 1983

- ^ "Vase of Lugalzagezi". British Museum.[dead link]

- ^ Winter, Irene J., "After the Battle Is Over: The ‘Stele of the Vultures’ and the Beginning of Historical Narrative in the Art of the Ancient Near East", Studies in the History of Art, vol. 16, pp. 11–32, 1985

- ^ Alster, Bendt., "Images and Text on the ‘Stele of the Vultures.’", Archiv Für Orientforschung, vol. 50, pp. 1–10, 2003

- ^ Grant, R.G. (2005). Battle. London: Dorling Kindersley Limited. ISBN 978-1-74033-593-5.

- ^ Cooper, Jerrold S., "Sumerian and Akkadian Royal Inscriptions, I. Presargonic Inscriptions", The American Oriental Society Translation Series 1, New Haven: American Oriental Society, 1986

- ^ Nies, James B., "A Net Cylinder of Entemena", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 36, pp. 137–39, 1916

- ^ Barton, George A., "A New Inscription of Entemena", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 262–65, 1931

- ^ Gadd, C. J., "Entemena : A New Incident", Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 125–26, 1930

- ^ A. Deimel, "Die Reformtexte Urukaginas", Or. 2, 1920

- ^ Foxvog, Daniel A., "A New Lagaš Text Bearing on Uruinimgina’s Reforms", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 46, pp. 11–15, 1994

- ^ Lambert, Maurice, "La guerre entre Urukagina et Lugalzagesi", Rivista Degli Studi Orientali, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 29–66, 1966

- ^ Stephens, Ferris J., "Notes on Some Economic Texts of the Time of Urukagina", Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale, vol. 49, no. 3, 1955, pp. 129–36

- ^ Joachim Marzahn, "Altsumerische Verwaltungstexteaus Girsu/Lagaš. Vorderasiatische Schriftdenkmälerder Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, Neue Folge Heft IX (Heft XXV), Berlin, Akademie-Verlag, 1991

- ^ Barton, George A., "The Babylonian Calendar in the Reigns of Lugalanda and Urkagina", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 251–71, 1911

- ^ Schrakamp, Ingo, "Irrigation in 3rd millennium southern Mesopotamia: cuneiform evidence from the Early Dynastic IIIB City-State of Lagash (2475–2315 BC)", in Water Management in Ancient Civilizations, pp. 117-195, 2018

- ^ "MS 2814 – The Schoyen Collection". www.schoyencollection.com.

- ^ a b c Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-52062-6.

- ^ Crowe, D. (2014). War Crimes, Genocide, and Justice: A Global History. Springer. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-137-03701-5.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ a b c Heuzey, Léon (1895). "Le Nom d'Agadé Sur Un Monument de Sirpourla". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 3 (4): 113–117. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 23284246.

- ^ a b Thomas, Ariane; Potts, Timothy (2020). Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins. Getty Publications. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-60606-649-2.

- ^ "Musée du Louvre-Lens - Portail documentaire - Stèle de victoire du roi Rimush (?)". ressources.louvrelens.fr (in French).

- ^ McKeon, John F. X. (1970). "An Akkadian Victory Stele". Boston Museum Bulletin. 68 (354): 235. ISSN 0006-7997. JSTOR 4171539.

- ^ Thomas, Ariane; Potts, Timothy (2020). Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins. Getty Publications. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-60606-649-2.

- ^ Foster, Benjamin R. (1985). "The Sargonic Victory Stele from Telloh". Iraq. 47: 15–30. doi:10.2307/4200229. JSTOR 4200229. S2CID 161961660.

- ^ Volk, K., "Puzur-Mama und die Reise des Königs", Zeitschrift fiir Assyriologie und verwandte Gebiete, vol. 82 (ZA. 82), Berlin, 1992

- ^ Edzard, Sibylle, "Ur-Ningirsu I", Gudea and his Dynasty, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 7-11, 1997

- ^ Edzard, Sibylle, "Pirig-me", Gudea and his Dynasty, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 12-13, 1997

- ^ Suter, Claudia E, "Who are the Women in Mesopotamian Art from ca. 2334-1763 BCE?", Who are the Women in Mesopotamian Art from ca. 2334-1763 BCE?", Kaskal, vol. 5, 1000-1055, 2008

- ^ Heimpel, Wolfgang, "The Gates of the Eninnu", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 48, pp. 17–29, 1996

- ^ Edzard, Sibylle, "Ur-Baba", Gudea and his Dynasty, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 15-25, 1997

- ^ Zarins, Juris, "Lagash and the Gutians: a study of late 3rd millennium BC Mesopotamian archaeology, texts and politics", In Context: the Reade Festschrift, pp. 11-42, 2020

- ^ a b H. Steible, "Neusumerische Bau- und Weihinschriften, Teil 1: Inschriften der II. Dynastie von Lagas", FAOS9/1, Stuttgart 1991

- ^ Molina Martos, Manuel, and Massimo Maiocchi, "Pre-Ur III administrative cuneiform tablets in the British Museum. I. Texts from the archives of Gudea's Dynasty", Kaskal, vol. 15, pp. 1-46, 2018

- ^ Ira M. Price, "The great cylinder inscriptions A & B of Gudea: copied from the original clay cylinders of the Telloh Collection preserved in the Louvre. Transliteration, translation, notes, full vocabulary and sign-lifts", Volume 1 Volume 2, Hinrichs, 1899

- ^ Suter, Claudia E., "A New Edition of the Lagaš II Royal Inscriptions Including Gudea’s Cylinders", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 50, pp. 67–75, 1998

- ^ Suter, Claudia E. Gudea's temple building: A comparison of written and pictorial accounts", Brill, 2000 ISBN 978-90-56-93035-6

- ^ Bartash, Vitali, "Gudea's Iranian Slaves: An Anatomy of Transregional Forced Mobility", Iraq 84, pp. 25-42, 2022

- ^ Hansen, Donald P, "A sculpture of Gudea, governor of Lagash", Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 64.1, pp. 4-19, 1988

- ^ Year Names of Gudea at CDLI

- ^ Steinkeller, Piotr, "The Date of Gudea and His Dynasty", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 47–53, 1988

- ^ a b Michalowski, Piotr, "Networks of Authority and Power in Ur III Times", in From the 21st Century B.C. to the 21st Century A.D.: Proceedings of the International Conference on Neo-Sumerian Studies Held in Madrid, 22–24 July 2010, edited by Steven J. Garfinkle and Manuel Molina, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 169-206, 2013

- ^ Maeda, Tohru, "Two Rulers by the Name of Ur-Ningirsu in Pre-Ur III Lagash", acta sumerologica Japan 10, pp. 19–35, 1988

- ^ Finkelstein, J. J., "The Laws of Ur-Nammu", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 22, no. 3/4, pp. 66–82, 1968

- ^ Maekawa, Kazuya, "The erín-people in Lagash of Ur III times", Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale 70.1, pp. 9-44, 1976

- ^ Maekawa, Kazuya, "The agricultural texts of Ur III Lagash of the British Museum (V)", Acta Sumerologica 3, pp. 37-61, 1981

- ^ Maekawa, Kazuya, "The agricultural texts of Ur III Lagash of the British Museum (VIII)", ASJ, vol. 14, pp. 145-169, 1992

- ^ Zarins, Juris, "Magan Shipbuilders at the Ur III Lagash State Dockyards (2062-2025 BC)", in Intercultural Relations Between South and Southwest Asia. Studies in Commemoration of ECL During Caspers (1934–1996), Oxford: BAR International Series (1826), pp. 209-229, 2008

- ^ Frayne, Douglas, "Ibbi-Sîn E3/2.1.5", in Ur III Period (2112-2004 BC), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 361-392, 1997

- ^ E. Hammer. Multi-centric, marsh-based urbanism at the early Mesopotamian city of Lagash (Tell al-Hiba, Iraq). Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. Vol. 68, December 2022, 101458. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2022.101458

- ^ Pittman, Holly, et al., "Response to Emily Hammer’s article:“Multi-centric, Marsh-based urbanism at the early Mesopotamian city of Lagash (Tell al Hiba, Iraq)”", Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 2023

- ^ Koldewey, Robert (1887-01-01). "Die altbabylonischen Gräber in Surghul und El Hibba". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie (in German). 2 (Jahresband): 403–430. doi:10.1515/zava.1887.2.1.403. ISSN 1613-1150. S2CID 162346912.

- ^ [1]Nissen, Hans J., "Uruk and I", Cuneiform Digital Library Journal 2024 (1), 2024

- ^ Falkenstein, Adam, "Die Inschriften Gudeas von Lagaš", Analecta Orientalia 30, Rome: Biblical Institute Press, 1966

- ^ Amiaud, Arthur. "The Inscriptions of Telloh." Records of the Past, 2nd Ed. Vol. I. Ed. by A. H. Sayce, 1888. Accessed 19 Dec 2010. M. Amiaud notes that a Mr. Pinches (in his Guide to the Kouyunjik Gallery) contended ŠIR.BUR.LAki could be a logographic representation of "Lagash," but inconclusively.

- ^ Donald P. Hansen, "Al-Hiba, 1968–1969: A Preliminary Report", Artibus Asiae, 32, pp. 243–58, 1970

- ^ Donald P. Hansen, "Al-Hiba, 1970–1971: A Preliminary Report", Artibus Asiae, 35, pp. 2–70, 1973

- ^ Donald P. Hansen, "Al-Hiba: A summary of four seasons of excavation: 1968–1976", Sumer, 34, pp. 72–85, 1978

- ^ Vaughn E. Crawford, "Inscriptions from Lagash, Season Four, 1975–76", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, 29, pp. 189–222, 1977

- ^ "Excavations in Iraq 1989-1990". Iraq. 53: 169–182. 1991. doi:10.1017/S0021088900004277. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4200346. S2CID 249898405.

- ^ Hansen, D. P., "The Sixth Season at Al-Hiba", Mār Šipri 3 (1): 1–3, 1990

- ^ S. Renette, "Lagash I: The Ceramic Corpus from Al-Hiba, 1968–1990 A Chrono-Typology of the Pottery Tradition in Southern Mesopotamia during the 3rd and Early 2nd Millenium BCE", Brepols, 2021 ISBN 978-2-503-59020-2

- ^ E. Carter, "A surface survey of Lagash, al-Hiba", 1984, Sumer, vol. 46/1-2, pp. 60–63, 1990

- ^ Lagash Archaeological Project Official website

- ^ Ashby, Darren P., and Holly Pittman, "The Excavations at Tell al-Hiba–Areas A, B, and G", in Ancient Lagash Current Research and Future Trajectories - Proceedings of the Workshop held at the 10th ICAANE in Vienna, April 2016, pp. 87-114, 2022

- ^ Hammer, Emily, Elizabeth Stone, and Augusta McMahon. "The Structure and Hydrology of the Early Dynastic City of Lagash (Tell al-Hiba) from Satellite and Aerial Images". Iraq, vol. 84, pp. 1-25, 2022

- ^ Pittman, Holly, "Lagash Archaeological Project, Dhi Qar Province, Iraq: The First Four Seasons, 1LAP-4LAP, 2019-2022", Video Presentation for the Archaeological Institute of America, National Lecture Program, March 21, 2023

- ^ Iraq dig uncovers 5,000 year old pub restaurant - Phys.org - Asaad Niazi - February 15, 2023

- ^ Unearthing the archaeological passing of time at Lagash, a site in southern Iraq - Michele W. Berger, University of Pennsylvania - Phys.org - January 24, 2023

- ^ Current Excavations Season 4: Fall 2022 - Penn Museum, University of Pennsylvania

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p [2] Darren Ashby, "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash", Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations, 2017

- ^ Beld, S. G., "The queen of Lagash: ritual economy in a Sumerian State", Ph.D Dissertation, Near East Studies, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 2002

- ^ a b Hansen, Donald P. (1970). "Al-Hiba, 1968-1969, a Preliminary Report". Artibus Asiae. 32 (4): 243–258. doi:10.2307/3249506. ISSN 0004-3648. JSTOR 3249506.

- ^ Hansen, Donald P. (1973). "Al-Hiba, 1970-1971: A Preliminary Report". Artibus Asiae. 35 (1/2): 65. doi:10.2307/3249575. ISSN 0004-3648. JSTOR 3249575.

- ^ a b c d Donald P. Hansen, "Royal building activity at Sumerian Lagash in the Early Dynastic Period", Biblical Archaeologist, vol. 55, pp. 206–11, 1992

- ^ Bahrani, Zainab, "The administrative building at Tell Al Hiba, Lagash", (Volumes I and II), Ph.D Dissertation, New York University, 1989.

- ^ a b "Excavations in Iraq 1989-1990". Iraq. 53: 175. 1991. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4200346.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Marchesi, Gianni (January 2015). Sallaberger, Walther; Schrakamp, Ingo (eds.). "Toward a Chronology of Early Dynastic Rulers in Mesopotamia". History and Philology (ARCANE 3; Turnhout): 139–156.

- ^ a b c d e "Brief notes on Lagash II chronology [CDLI Wiki]". cdli.ox.ac.uk.

Further reading

[edit]- Al-Hamdani, Abdulameer, "The Lagash Plain During the First Sealand Dynasty (1721–1340 BCE)", in Ancient Lagash Current Research and Future Trajectories - Proceedings of the Workshop held at the 10th ICAANE in Vienna, April 2016, pp. 161–179, 2022

- Robert D. Biggs, "Inscriptions from al-Hiba-Lagash : the first and second seasons", Bibliotheca Mesopotamica. 3, Undena Publications, 1976, ISBN 0-89003-018-9

- R. D. Biggs, "Pre-Sargonic Riddles from Lagash", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 32, no. 1/2, pp. 26–33, 1973

- Vaughn E. Crawford, "Lagash", Iraq, vol. 36, no. 1/2, pp. 29–35, 1974

- Foxvog D.A., "Aspects of Name-Giving in Presargonic Lagash", in W. Heimpel – G. Frantz- Szabó (eds.), Strings and Threads: A Celebration of the Work of Anne Draffkorn Kilmer, Winona Lake, 59-97, 2011

- Goodman, Reed C., Steve Renette, and Elizabeth Carter, "The al-Hiba Survey Revisited", in Ancient Lagash Current Research and Future Trajectories - Proceedings of the Workshop held at the 10th ICAANE in Vienna, April 2016, pp. 115–122, 2022

- Hansen, D. P., "Lagaš. B. Archäologisch", Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie 6: 422–30, 1980–1983

- Harper, Prudence O., "Tomorrow We Dig! Excerpts from Vaughn E. Crawford’s Letters and Newsletters from al-Hiba"., Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honor of Donald P. Hansen, edited by Erica Ehrenberg, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 89–102, 2002 ISBN 978-1-57506-055-2

- Hussey, Mary Inda, "A Statuette of the Founder of the First Dynasty of Lagash", Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale 28.2, pp. 81–83, 1931

- Jagersma, Bram, "The calendar of the funerary cult in ancient Lagash", Bibliotheca Orientalis 64.3, pp. 289–307, 2007

- Kenoyer, J. M., "Shell artifacts from Lagash, al-Hiba", Sumer 46 (1/2), pp. 123–144, 1989-1990

- [3] Marchesi, Gianni, "Notes on Two Alleged Literary Texts from Al-Hiba/Lagaš", Studi Epigrafici e Linguistici sul Vicino Oriente Antico 16, pp. 3–17, 1999

- Maeda T., "Work Concerning Irrigation Canals in Pre-Sargonic Lagash", Acta Sumerologica Japaniensia 6, 33-53, 1984

- Maekawa K., "The Development of the é-mí in Lagash during Early Dynastic III", Mesopotamia 8-9, 77-144, 1973-1974

- Mercer, Samuel AB, "Divine service in Early Lagash", Journal of the American Oriental Society, pp. 91–104, 1922

- Mudar, K., "Early Dynastic III animal utilization in Lagash: a report on the fauna of Tell al-Hiba", Journal of Near Eastern Studies 41 (1), pp. 23–34, 1982

- [4] Muhammed, Qassim M., Muhanad Alrakabi, and Jabbar M. Rashid, "Assessment of natural radioactivity in building material of the ancient city of Tell-Al Hiba in Thi-Qar southern Iraq", Res Militaris 12.2, pp. 3551–3561, 2022

- Ochsenschlager, Edward, "Mud objects from al-Hiba: a study in ancient and modern technology", Archaeology 27.3, pp. 162–174, 1974

- Pittman, Holly, and Darren P. Ashby, "A Report on the Final Publication of the Excavations of the Tell al-Hiba Expedition, 1968–1990", in Ancient Lagash Current Research and Future Trajectories - Proceedings of the Workshop held at the 10th ICAANE in Vienna, April 2016, pp. 115–122, 2022

- Prentice, R., "The exchange of goods and services in pre-Sargonic Lagash", Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 2010

- Renette, Steve, "Some Observations on Regional Ceramic Traditions at al-Hiba/Lagash", in Ancient Lagash Current Research and Future Trajectories - Proceedings of the Workshop held at the 10th ICAANE in Vienna, April 2016, pp. 145–160, 2022

- Renette, Steve, "Painted Pottery from Al-Hiba: Godin Tepe III Chronology and Interactions between Ancient Lagash and Elam", Iran, vol. 53, pp. 49–63, 2015

- Thomas, Ariane, "The Faded Splendour of Lagashite Princesses: A Restored Statuette from Tello and the Depiction of Court Women in the Neo-Sumerian Kingdom of Lagash", Iraq 78, pp. 215–239, 2016

- Garcia-Ventura, Agnès, and Fumi Karahashi, "Overseers of textile workers in presargonic Lagash", KASKAL, pp. 1–19, 2016

External links

[edit]- Drone photos reveal an early Mesopotamian city made of marsh islands - Science News - October 13, 2022

- University of Pennsylvania Lagash Current and Legacy excavations page

- Excavations in the Swamps of Sumer - Vaughn E. Crawford - Expedition Magazine Volume 14 Issue 2 1972

- University of Cambridge Lagash project

- Lagash excavation site photographs at the Oriental Institute Archived 2010-06-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Lagash Digital Tablets at CDLI

- The Al-Hiba Publication Project

- The Al-Hiba Publication Project - digitization

- 5,000-Year-Old Tavern With Food Still Inside Discovered in Iraq

Lagash

View on GrokipediaGeography and Environment

Location and Physical Setting

Lagash was an ancient Sumerian city-state situated in southern Mesopotamia, within the modern Dhi Qar Governorate of Iraq, approximately 24 kilometers east of the town of Shatra.[3] The primary archaeological site associated with Lagash proper is Tell al-Hiba, located at coordinates 31.4025° N latitude, amid the flat alluvial plains formed by sediment deposits from the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.[3] These plains characterized the physical setting, providing fertile soil for agriculture through seasonal inundations and engineered irrigation systems, though the region also featured extensive marshes and watercourses that influenced urban development.[4] The Lagash city-state encompassed multiple discrete urban centers, including Girsu (modern Telloh) and Nina, interconnected by canals such as the Going-to-Niĝin Canal, which facilitated transportation and agriculture in the deltaic environment.[4] This marsh-based landscape, with its levees, lagoons, and estuaries, supported a multi-centric urbanism where settlements were bounded by walls and natural or artificial waterways, adapting to the dynamic hydrology of the lower Mesopotamian floodplain.[5] The semi-arid climate, marked by hot summers and reliance on river flooding for water, underscored the environmental challenges and opportunities that shaped Lagash's growth during the Early Dynastic period (c. 2900–2350 BCE).[6]Natural Resources and Environmental Challenges

Lagash occupied marshy alluvial plains in southern Mesopotamia, where fertile silt from the Tigris and Euphrates rivers enabled intensive agriculture supported by irrigation canals. The region's primary natural resources encompassed abundant freshwater for crop cultivation, clay-rich soils suitable for brick-making and pottery, and marsh vegetation including reeds exploited for construction, mats, and boats. Early Sumerian farmers in the Lagash area utilized tidal flows from the Persian Gulf via short canals to irrigate fields efficiently, fostering surplus production of staples like barley without requiring large-scale infrastructure initially.[7][8][5] Environmental challenges arose from the region's low rainfall, compelling dependence on river inundation and artificial irrigation, which promoted soil salinization through salt accumulation in poorly drained clay soils. Archaeological investigations at Tell al-Hiba reveal evidence of a catastrophic flood around 2350 BCE, depositing thick silt layers and causing site-wide destruction, likely linked to intensified river dynamics under rulers like Lugalzagesi of Uruk. Compounding this, the late third-millennium BCE saw worsening salinity in Lagash's fields, diminishing yields as irrigation evaporated salts into the topsoil. Hydrological shifts, including the recession of Gulf tides due to delta progradation, triggered ecological instability with erratic flooding, prolonged droughts, and heightened salinity, straining the city's adaptive capacity.[9][10][11]Historical Overview

Pre-Dynastic and Early Foundations

The site of Lagash, identified with modern Tell al-Hiba in Dhi Qar Governorate, southern Iraq, shows evidence of early occupation during the Ubaid period (c. 5500–4000 BCE), when small villages emerged in the Tigris-Euphrates floodplain. Ubaid remains recovered from secondary contexts at Tell al-Hiba, including painted pottery, indicate modest settlements reliant on marsh-based subsistence economies featuring fish, birds, and mollusks.[6] These early communities were part of a broader pattern of self-sufficient hamlets in estuarine environments, preceding more complex social structures.[1] Settlement continuity extended into the Uruk period (c. 4000–3100 BCE), marked by the Urban Revolution and river stabilization following sea level changes, which facilitated agricultural intensification and population growth. At Lagash, this era saw the initial formation of a multi-centric polity, with Tell al-Hiba developing alongside nearby centers like Girsu (Tell Lo) and Niĝin (Tell Zurghul), linked by canals such as the Going-to-Niĝin.[1][2] The polity encompassed several urban centers, including Lagash proper (Tell al-Hiba), the religious and administrative hub Ĝirsu (Tello), Niĝin (Tell Zurghul), and the seaport Gu'abba. The site's expansion to approximately 600 hectares reflects emerging urbanism in a fertile delta zone, though primary Uruk layers remain sparsely documented compared to Early Dynastic remains.[3] By the Early Dynastic period (c. 2900–2350 BCE), prior to the First Dynasty under Ur-Nanshe (c. 2520 BC), Lagash had coalesced into a large city-state with distinct walled neighborhoods, temples, and administrative complexes. In the Early Dynastic IIIa period, Ĝirsu served as the capital, with its tutelary god Ninĝirsu as the chief deity of the local pantheon. Excavations at Tell al-Hiba, including those by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and New York University (1968–1990), uncovered evidence of religious and craft activities in marsh-adapted urban sectors, highlighting foundational economic and ideological systems.[2] Remote sensing and surface surveys confirm spatial organization bounded by walls and watercourses, underscoring adaptive urbanism in a dynamic hydrological landscape. This pre-dynastic phase laid the groundwork for Lagash's political prominence through integrated temple economies and territorial control.[1]First Dynasty (c. 2520–2260 BC)

The First Dynasty of Lagash, spanning approximately 2520–2260 BC, marked the city's emergence as an independent power in southern Mesopotamia during the Early Dynastic III period. Founded by Ur-Nanshe around 2500 BC, the dynasty's rulers asserted control through temple construction, administrative reforms, and military campaigns, particularly against neighboring Umma over the fertile Gu'edena ("The Edge of the Plains") region sacred to the god Ningirsu. This border conflict is the earliest well-documented case of a war between states, consisting of intermittent fighting over generations amid the division of Sumer into competing city-states vying for agricultural land and water resources in a period of dense urbanization. Primary sources are royal inscriptions from Lagash, introducing a Lagash-centric bias to the historical record. The feud predated the dynasty, with relations already tense during the reign of Mesilim, king of Kish, who acted as arbiter and demarcated the border.[1] In Sumerian ideology, land was conceptualized as the property of the gods, with the ruler serving as its administrator. The border between Lagash and Umma was regarded as having divine origin: inscriptions claim that Enlil, chief god of the Sumerian pantheon, divided the land between Ninĝirsu (patron of Lagash) and Shara (patron of Umma). Lagashite rulers portrayed their campaigns as a divine mission to retrieve territory belonging to Ninĝirsu, who was described in inscriptions as intervening directly on the battlefield in their favor.[1] Inscriptions from sites like Girsu (Telloh), al-Hiba, and Zurghul provide primary evidence of their activities, including building projects and territorial claims.[1] Ur-Nanshe, credited as the dynasty's initiator, transitioned Lagash from tributary status under Uruk to dynastic kingship (ensi). His limestone reliefs and inscriptions record the importation of materials like copper from the east and the erection of temples dedicated to deities such as Nanše and Ningirsu, emphasizing economic networks and religious patronage.[12] His son Akurgal briefly ruled before Eannatum, Ur-Nanshe's grandson, ascended circa 2450 BC and expanded Lagash's influence through conquests.[1] Eannatum's reign featured decisive victories over Umma, culminating in the imposition of a boundary treaty enforced by oaths to the gods. The Stele of the Vultures, erected around 2450 BC, commemorates his triumph, depicting phalanx formations—among the earliest visual records of organized infantry—and vultures devouring the enemy dead, symbolizing divine favor from Inanna and Ningirsu.[1] This monument, found fragmented at Girsu and housed in the Louvre (AO 16), underscores the dynasty's martial prowess and the role of propaganda in legitimizing rule.[1] Eannatum's campaigns reportedly extended to cities like Ur and Kish, though sustained control remains debated due to limited corroborating evidence beyond Lagashite texts.[1] Successors Enannatum I and Entemena maintained defenses against Umma's incursions. Enannatum I, active mid-24th century BC, clashed with Umma's Ur-Lumma, reinforcing territorial markers and temple dedications like the Ibgal to Nanše.[1] Entemena, circa 2400 BC, repelled Il of Umma, as detailed in inscriptions on a silver vase fragment (Louvre AO 2674) and the Cone of Entemena, which narrate the conflict's resolution through Ningirsu's intervention and a subsequent pact. These artifacts highlight ongoing irrigation disputes central to Sumerian city-state rivalries, where control of canals determined agricultural surplus.[1] The dynasty waned under Urukagina (circa 2350–2300 BC), whose inscriptions detail anti-corruption edicts abolishing certain fees and restoring temple lands to curb elite abuses, reflecting internal administrative strains.[1] However, Lagash fell to Lugalzagesi of Umma (who later ruled Uruk), whose offensives sacked Girsu, dismantled the dynasty's monuments, and reduced Urukagina's control to a diminished territory centered on Ĝirsu. Lugalzagesi claimed control over all of Sumer and adopted the title "king of the land," contextualized by emerging traditions of kingship and political unification. This collapse, evidenced by destruction layers at archaeological sites, illustrates the fragility of Sumerian polities amid resource competition and shifting alliances.[1]Akkadian Domination (c. 2334–2154 BC)

Sargon of Akkad initiated the domination of Lagash circa 2334 BC by defeating Lugalzagesi of Umma, who had previously conquered and sacked the city-state, thereby incorporating Lagash into the emerging Akkadian Empire that unified much of Mesopotamia under centralized Semitic rule.[1] This conquest followed Sargon's victories over other Sumerian centers like Uruk and Ur, marking the end of Lagash's independence after its First Dynasty and integrating it into a vast territorial system extending from the Persian Gulf to northern Syria.[13] During the Akkadian period (c. 2334–2154 BC), Lagash was governed by local officials titled ensi, appointed or overseen by Akkadian authorities to ensure loyalty and tribute extraction, with examples including Lugalushumgal as a vassal ensi around 2200 BC.[14] Archaeological evidence from Tell al-Hiba, the main urban center of Lagash, indicates a contraction of settlement toward the center-west area, suggesting reduced population density or economic activity amid imperial oversight and resource redirection to Akkad.[1] Administrative reforms under Sargon and successors like Rimush and Manishtushu emphasized Akkadian personnel in key roles, fostering bilingual administration where Akkadian script and language supplemented Sumerian traditions, though local temple cults such as those of Ningirsu persisted under imperial patronage.[13] The period saw cultural and artistic influences from Akkad, including the adoption of imperial iconography in seals and monuments, but Lagash's integration contributed to the empire's overextension, exacerbated by rebellions and environmental stresses.[1] By circa 2193 BC, amid Gutian incursions that weakened Akkadian control, the ensi Puzer-Mama asserted independence, transitioning Lagash toward its Second Dynasty revival, though nominal imperial dominance lingered until the empire's collapse around 2154 BC.[14]Second Dynasty and Independence (c. 2144–2047 BC)

Following the collapse of the Akkadian Empire circa 2154 BC and the ensuing Gutian incursions that weakened central authority, Lagash reasserted its autonomy under local ensi (governors or priest-rulers), initiating the Second Dynasty around 2144 BC. This period marked a revival of Sumerian cultural and religious traditions amid regional fragmentation, with Lagash functioning as an independent city-state free from imperial oversight. Archaeological evidence, including inscriptions and architectural remnants from sites like Girsu (modern Telloh), attests to intensified temple construction and economic activity, reflecting rulers' emphasis on divine favor and legitimacy through piety rather than conquest.[1] The dynasty's most prominent ruler, Gudea, governed from approximately 2144 to 2124 BC, succeeding his father-in-law Ur-Baba and focusing on monumental building projects without recorded military campaigns. Gudea's inscriptions detail the importation of raw materials from distant regions, such as cedar wood from the Amanus Mountains (modern Lebanon), copper from northern Mesopotamia, and diorite stone from Magan (likely Oman), to reconstruct temples like the E-ninnu dedicated to the city-god Ningirsu. Over twenty surviving diorite statues of Gudea, many inscribed with prayers and dedications, portray him in seated or standing poses with hands clasped in supplication, underscoring his self-presentation as a devout intermediary between gods and people. These artifacts, excavated primarily at Girsu and now housed in museums like the Louvre, provide direct evidence of artistic sophistication and resource networks sustaining Lagash's prosperity.[15][16] Gudea was succeeded by his son Ur-Ningirsu, who ruled circa 2124 to 2118 BC and perpetuated the dynasty's policies of temple patronage and administrative continuity. Ur-Ningirsu's inscriptions record further dedications and construction, including expansions at Ningirsu's sanctuary, maintaining the economic momentum through trade and agriculture supported by Lagash's irrigation systems. Later rulers, such as Nammahani (circa 2113–2110 BC), navigated alliances with lingering Gutian influences but faced external pressures, culminating in Lagash's subjugation by Ur-Nammu of Ur around 2112 BC, which integrated the city-state into the Ur III polity by 2047 BC. This era's emphasis on religious infrastructure and peaceful governance contributed to a cultural zenith, evidenced by cuneiform texts and votive objects, before broader Neo-Sumerian consolidation.[17][14]Integration into Ur III and Decline (c. 2112–2004 BC)

Following the end of the Second Dynasty of Lagash circa 2047 BC, the city-state was incorporated into the Third Dynasty of Ur through military conquest led by Ur-Nammu, the empire's founder (r. c. 2112–2095 BC). Ur-Nammu defeated and killed Namkhani, the last independent ruler of Lagash, thereby eliminating its autonomy and redirecting its trade networks—particularly access to resources from Dilmun, Magan, and Meluhha—toward Ur.[18] This integration transformed Lagash from a sovereign entity into a provincial district under centralized Ur III administration, with Girsu emerging as a primary center for governance and record-keeping. During the Ur III period (c. 2112–2004 BC), Lagash functioned as one of the empire's most vital provinces, second in administrative output only to Umma, yielding thousands of cuneiform tablets documenting grain production, labor allocation, and land tenure. Ensis (governors) appointed by Ur III kings oversaw extensive agricultural operations, leveraging Lagash's fertile plains and canal systems to supply the empire's food requirements, effectively positioning it as a "breadbasket" for the capital at Ur.[1] These archives reveal a highly bureaucratized system, with detailed tracking of corvée labor, temple estates, and taxation, underscoring Lagash's economic subordination yet infrastructural importance within the Neo-Sumerian state's redistributive economy.[19] Lagash's decline coincided with the broader collapse of Ur III circa 2004 BC, triggered by Elamite invasions that sacked Ur and disrupted imperial control across southern Mesopotamia. Without reasserting independence, Lagash fragmented amid the ensuing power vacuum, as authority shifted to emerging dynasties in Isin and Larsa; its urban centers, including Girsu, saw reduced political centrality and eventual abandonment by the late third millennium BC.[20] This marked the terminal phase of Lagash's prominence, with no subsequent revival as a major city-state, reflecting the empire's overextension and vulnerability to external pressures rather than localized factors alone.[1]Governance and Administration

Rulership Structure

The rulership of Lagash centered on the ensi, a title for the chief governor or ruler who served as the terrestrial agent of the city's patron deity, Ningirsu, overseeing both sacred and profane affairs.[14] This position integrated religious authority with administrative, military, and judicial functions, reflecting the theocratic nature of Sumerian city-states where the ensi derived legitimacy from divine favor, often confirmed through omens or oracles.[21] Unlike the broader lugal (king) title more common in expansive empires, Lagash consistently employed ensi for its independent rulers, emphasizing local governance tied to temple institutions rather than distant overlordship.[22] The ensi's powers encompassed command of the military, as demonstrated by Eannatum's victories over Umma around 2450 BC, management of irrigation systems vital for agriculture, and adjudication of disputes, including boundary conflicts resolved via stelae and treaties.[23] Temple complexes like the É-ningirsu served as economic hubs under ensi supervision, where land allocations, labor drafts, and tribute collections supported state operations; for instance, Lugalanda's corrupt administration in the mid-24th century BC involved expropriating temple properties, prompting reforms under Urukagina.[23] Subordinate officials, including scribes and overseers (nu-banda), executed daily governance, recording transactions on clay tablets that reveal a bureaucratic hierarchy focused on accountability to the ensi and gods. Succession typically followed familial lines, with sons or relatives inheriting the role after demonstrating piety and competence, as seen in the dynasty from Ur-Nanshe (c. 2520 BC) to Gudea, though divine selection via dreams or rituals could intervene.[15] Gudea exemplified ideal rulership by prioritizing temple construction—erecting over 15 structures—and legal equity, issuing edicts against usury and ensuring fair weights, which fostered prosperity amid post-Akkadian recovery around 2144–2124 BC.[24] During periods of external domination, such as Akkadian rule (c. 2334–2154 BC), local ensis operated as vassals, but regained autonomy by adapting to imperial demands while preserving core Lagashite traditions.[25] This structure persisted until integration into the Ur III empire (c. 2112 BC), where Lagash ensis yielded to centralized kingship.[14]Legal and Social Reforms

Urukagina, the last ensi of Lagash's First Dynasty (c. 2350–2330 BC), promulgated edicts inscribed on clay cones that addressed widespread abuses by powerful officials and temple authorities, marking the earliest known proclamations of social and economic restoration in Mesopotamian history.[26] These texts detail how previous rulers had imposed excessive levies, such as treating citizens' goods as if owed to the palace, and exploiting vulnerable groups including widows and orphans by seizing their property or oxen for minor debts.[27] Urukagina's measures restored protections, declaring that the house of a widow or orphan could no longer be seized for debt, and limited fees for services like boat usage from one shekel of silver to one ban of barley, approximately one-sixth the prior amount.[28] The edicts also abolished debt-based enslavement, granting amnesty to debtors and freeing those bound into servitude, while prohibiting elites from forcibly acquiring the homes, fields, or livestock of commoners without consent.[29] Punishments for crimes like theft and murder were maintained, but administrative corruption was curtailed by dismissing corrupt overseers (maškim) and reducing the influence of tax collectors.[30] Scholarly analysis of the cone inscriptions, preserved in fragments from Girsu, interprets these as restorative justice decrees rather than a comprehensive legal code, aimed at reestablishing equilibrium after perceived moral and economic decay under prior governance.[31] The term ama-gi ("return to mother" or freedom), first appearing here, signified liberation from bondage, influencing later Mesopotamian concepts of emancipation.[29] Under Gudea of the Second Dynasty (c. 2144–2124 BC), administrative policies emphasized equity in land distribution and debt relief, though evidence is sparser and derived mainly from dedicatory inscriptions rather than explicit reform texts.[32] Gudea permitted daughters to inherit family estates in the absence of male heirs, diverging from stricter patrilineal norms and promoting familial stability amid post-Akkadian recovery.[33] These actions supported broader social welfare, including canal maintenance for equitable irrigation access, but lacked the detailed proclamations of Urukagina, focusing instead on pious governance intertwined with temple-building.[34] Overall, Lagash's reforms reflected a hierarchical society—comprising ensi, priests, scribes, free farmers, and dependents—where rulers periodically intervened to mitigate elite overreach, fostering short-term stability without establishing enduring statutory law.[35]Economy and Daily Life

Agricultural Systems and Irrigation

The economy of ancient Lagash depended heavily on irrigated agriculture, which transformed the arid Mesopotamian plain into productive fields capable of supporting dense urban populations. Primary crops included barley as the staple cereal, valued for its drought tolerance and use in beer production and bread, supplemented by emmer wheat and bread wheat for diversified yields. Date palms were widely grown for fruit, fiber, and structural materials, while subsidiary crops encompassed chickpeas, lentils, onions, and other vegetables cultivated in shaded orchards or flood-irrigated plots.[36][37] Early agricultural systems in Lagash and broader Sumer leveraged tidal dynamics in the marshy Euphrates delta, where semi-diurnal tides facilitated natural irrigation through short primary canals (1–2 km long) aligned with river channels, allowing flood-recession farming without massive engineering until around the mid-third millennium BC. This tidal regime supported intensive barley cultivation by timing plantings to tidal inundations, yielding multiple irrigations per season as noted in Sumerian agronomic texts. As tidal influences diminished due to river avulsion and sediment buildup, Lagash transitioned to engineered river-based systems, necessitating communal labor for dike maintenance and canal excavation to mitigate salinization risks from over-irrigation.[7][38][8] Archaeological evidence from Girsu, the religious center of Lagash, documents extensive canal networks, including regulators—stone or brick sluices that diverted and measured water flows into secondary distributaries for field-level irrigation. Radiocarbon dating of organic sediments in these canals confirms construction phases from the Early Dynastic IIIb period (c. 2500–2340 BC) onward, with intensification under Ur III administration (c. 2112–2004 BC) integrating waterways into economic accounting via cuneiform records of labor allocations. Such systems, while enabling surplus production, sparked interstate conflicts, as evidenced by Early Dynastic disputes with Umma over shared canal boundaries, where rulers like Enmetena inscribed claims to water rights on stelae.[39][40][41][42]Trade, Crafts, and Labor Organization

The economy of Lagash was predominantly managed through its temples and palaces, which coordinated production, distribution, and labor allocation via cuneiform administrative records.[43] These institutions oversaw workshops where artisans produced goods ranging from ceramics and textiles to metalwork and stone sculpture, with raw materials often sourced locally or imported to support temple construction and elite demands.[24] Labor was stratified, including dependent temple personnel, corvée workers mobilized for irrigation maintenance and building projects, and skilled specialists like stonecutters and metal smiths whose outputs are attested in archaeological finds such as diorite statues and bronze vessels.[14] Crafts flourished under rulers like Gudea (c. 2144–2124 BC), who commissioned high-quality artworks including over 20 surviving diorite statues and libation vases, requiring advanced techniques in quarrying, transport, and polishing hard stones unavailable locally.[24] Artisans operated in temple-attached ateliers, as evidenced by inscriptions detailing material procurement for the Eninnu temple at Girsu, where laborers included bricklayers and sculptors organized hierarchically under overseers.[44] Earlier, under Urukagina (c. 2350 BC), reforms curbed exploitative practices by elites, such as reducing boat taxes on wood transport and freeing debt-bound laborers, aiming to restore balance between temple obligations and commoner burdens without evidence of formal guilds.[45] Trade networks extended internally via riverine routes along the Euphrates and Tigris, exchanging Lagash's agricultural surplus—barley, wool, and dates—for timber and metals from neighboring regions, and internationally under Gudea, who dispatched expeditions to acquire cedar from Lebanon, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, gold from Anatolia, and diorite from the Magan region (likely Oman or Indus periphery).[46] These ventures, documented in cylinder seals and inscriptions, emphasized diplomacy over conquest, with imports funneled into sacred architecture rather than widespread commercialization, reflecting a redistributive system where palace-temple elites controlled surplus flows.[32] Preceding rulers like Ur-Nanshe (c. 2494–2465 BC) secured wood tribute from Dilmun (Bahrain), underscoring Lagash's integration into Gulf trade circuits by the Early Dynastic period.[14]Religion and Cult Practices

Deities and Temples

Ningirsu served as the patron deity of Lagash, revered as a warrior god embodying thunder, rain, irrigation, and fertility, with his primary cult center in the district of Girsu.[14] The E-ninnu, or "House of the White Thunderbird," formed the core of his temple complex in Girsu, functioning as the state's chief sanctuary from the Early Dynastic period onward, where rulers dedicated victories and resources to honor him.[47] Archaeological excavations have uncovered multiple phases of this temple, including a 4,500-year-old structure linked to Ningirsu as a mighty thunder god, underscoring its enduring religious prominence.[48] Bau, a goddess associated with healing, protection, and fertility, held significance in Lagash as a local deity, often depicted with canine attributes symbolizing her therapeutic role. Her worship integrated into the broader pantheon, with temples dedicated to her in the region, though specific sites remain unlocated amid the city's ruins. Rulers like Gudea of the Second Dynasty undertook extensive temple constructions and renovations across Lagash, including expansions to the Eninnu for Ningirsu and shrines for associated deities such as Ningishzida, reflecting the ensi's role as divine intermediary responsible for maintaining cultic infrastructure.[49] These efforts involved importing materials like cedar and diorite for sacred buildings, as documented in Gudea's inscriptions emphasizing piety and prosperity under divine favor.[49] Nanše, an oracle goddess and daughter of Enki, received veneration in Lagash's coastal district of Sirara, where her temple facilitated prophetic consultations and justice rituals, highlighting the city's diverse sacred landscape beyond Girsu's martial focus. The Anzû bird, emblematic of Ningirsu, appeared in temple iconography as a master of animals motif, symbolizing divine power and protection over Lagash. Overall, the religious system prioritized Ningirsu while incorporating a network of subsidiary cults, with temples serving as economic hubs distributing offerings and sustaining priestly hierarchies.[50]Rituals and Religious Artifacts

Rituals in Lagash centered on the worship of Ningirsu, the patron deity, through sacrifices, libations, and offerings performed in temples like the Eninnu (House of the White Thunderbird). The central act of divine service involved presenting food, drink, and animal sacrifices at the god's cult statue in the temple cella, with ancillary spaces for prayers and processions. Rulers such as Gudea (c. 2144–2124 BC) enacted consecration rites during temple foundations, including city purification, bans on burials and debt enforcement, and incubation dreams seeking divine blueprints for construction.[16][51][52] Gudea's cylinders detail extensive rituals for the Eninnu rebuild, encompassing material transport ceremonies, labor organization under divine oversight, and dedication festivals culminating in the god's symbolic entry into the completed structure. Annual observances featured communal feasting tied to Ningirsu, evidenced by favissae—ritual pits—containing over 1,000 caprine bones and nearly 300 vessels, primarily conical beakers (84%) and bowls (9%), suggesting standardized liquid offerings and shared sacrifices involving broad participation beyond elites. Strontium isotope analysis confirms locally sourced animals, aligning with practices of regional provisioning for cultic events.[53][54] Key religious artifacts comprised foundation deposits like inscribed clay cones embedded in walls to channel divine power, pegs symbolizing stability and held by horned figures, and dedicatory tablets buried beneath structures. Libation vases, such as Entemena's (c. 2400 BC), facilitated pouring offerings, while diorite votive statues of Gudea in prayer postures—hands clasped, often holding a libation vessel—served as perpetual intercessors for the ruler's piety and the city's prosperity. Excavations at Girsu yielded cultic jars, offering bowls, and burnt surfaces indicative of ongoing sacrificial activity in the sacred precinct.[16]Art, Culture, and Material Legacy

Sculpture and Iconography