Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lajat

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

The Lajat (Arabic: اللجاة/ALA-LC: al-Lajāʾ), also spelled Lejat, Lajah, el-Leja or Laja, is the largest lava field in southern Syria, spanning some 900 square kilometers. Located about 50 kilometers (31 mi) southeast of Damascus, the Lajat borders the Hauran plain to the west and the foothills of Jabal al-Druze to the south. The average elevation is between 600 and 700 meters above sea level, with the highest volcanic cone being 1,159 meters above sea level. Receiving little annual rainfall, the Lajat is largely barren, though there are scattered patches of arable land in some of its depressions.

The region has been known by a number of names throughout its history, including "Argob" (Hebrew: ארגוב ’Argōḇ, sometimes vocalized as Argov[1]) in the Hebrew Bible and "Trachonitis" (Greek: Τραχωνῖτις) by the Greeks, a name under which it is mentioned in the Gospel of Luke (Luke 3, Luke 3:1). Long inhabited by Arab groups, it saw development under the Romans, who built a road through the center of the region connecting it with the empire's province of Syria. The pagan cults that predominated in Trachonitis during the Roman and pre-Roman era persisted through much of the Byzantine era, until the 6th century when Christianity became dominant. During Byzantine rule, Trachonitis experienced a massive building boom with churches, homes, bathhouses and colonnades being constructed in numerous villages, whose inhabitants remained largely Arab.

The region was abandoned at some point, only to be repopulated by refugees from other regions of Syria during the Mongol invasions in the 13th century. This earned the region its modern Arabic name, al-Lajāʾ, meaning "the refuge". During early Ottoman rule in the 16th century, al-Lajat contained numerous agricultural villages and farms, but by the 17th century, the region was all but abandoned. Local Bedouin tribes, such as the Sulut, increasingly used the region for grazing their flocks, and Druze migrants from Mount Lebanon began settling the area in the early 19th century. Today, the population is mixed, with Druze inhabiting its central and eastern areas, and Muslims and Melkite Christians living in villages along its western edge.

Etymology

[edit]

Lajat's ancient name "Trachonitis" signifies the land associated with the trachon, "a rugged stony tract." There are two volcanic districts south and east of Damascus, to which the Greeks applied this name: that to the northwest of the mountain of Jabal al-Druze (Jabal Hauran) is called in Arabic, el-Leja, which means "the refuge" or "asylum".

Geography

[edit]The Lajat is situated in southeastern Syria, spanning a triangle-shaped area between the 45-kilometer Izra'-Shahba line in the south 48 kilometers northward to the vicinity of Burraq.[2] It is about 50 kilometers south of Damascus.[2] Its northern border is roughly marked by the Wadi al-Ajam gorge, which separates it from the Ghouta countryside of Damascus.[2] It is bordered to the east by the Ard al-Bathaniyya region, to the southeast by Jabal al-Druze (also called Jabal Hauran), to the south by the Nuqrah (southern Hauran plain) and to the northwest by Jaydur (northern Hauran plain).[2]

Topography

[edit]The Lajat's average elevation is between 600 and 700 meters above sea level,[2] and it is higher than the surrounding plains.[3] Many of its volcanic cones are higher than 1,000 meters above sea level, with the highest, just west of Shahba, at 1,159 meters.[2] In general the volcanic cones and mounds rise 20 to 30 meters above the lava fields.[4]

Much of the Lajat is covered by gray, disintegrated lava fields that form jagged basalt boulders, though there are some areas of smoother, rocky ground punctured with holes.[5] The holes were formed from gas bubbles caused by cooling lava that flowed over the uneven landscape.[5] Among the mostly barren landscape are depressions with far less rocky ground than the rest of the Lajat.[2] The depressions are called ka′ in Arabic and have average diameters of 100 meters.[2] The depressions are likely the result of earlier volcanic eruptions.[2] The depressions represented scattered patches of arable land among lava and fewer larger areas of fertile ground.[3] The few wadis (dried up streams) of the Lajat are generally shallow and broad.[5] Even fewer than the wadis are deep fissures that form caves or reservoirs.[5]

Water sources

[edit]Springs and underground water sources in the Lajat are scarce and most water is supplied by cisterns.[2] Shortages of water are particularly severe during the summer months.[3] While during the Lajat's ancient history, its inhabitants stored water from winter rainfall in reservoirs built near homes, by the early 20th century, these reservoirs had long fallen into disrepair.[6] Thus, by the modern era, every village contained rectangular cisterns to store rainwater, which serves as the main source of water.[7]

History

[edit]Antiquity

[edit]Early history

[edit]In ancient times, Trachonitis included the regions of Lajat and the Tulul as-Safa to its east.[2] For much of the 1st and 2nd millenniums BC, the region lacked political significance and was influenced by the Damascus-based Arameans and the Israelites.[2] Trachonitis was annexed by the Seleucid Empire in the 2nd century BC. During this period, the region was a frontier zone between the southern Nabataeans and northwestern Itureans, both Arab groupings.[2]

Roman period

[edit]In 24 BC, the Roman Empire conquered Syria and assigned the region of Trachonitis, which was inhabited by nomadic marauders and cattle herders living in caves, to the authority of Herod the Great, king of Judaea.[8][9][2] The area was not part of Herod's original kingdom in 40 BCE but was given to him by the Romans by the end of 27 BCE.[10] To address the issue of local brigands, Herod settled 3,000 Idumaeans in Trachonitis.[11][12][13] Later, around 7 BCE,[14] Herod invited Zamaris, a Jew from Babylonia, and his contingent of 500 mounted archers to settled the village of Bathyra in Batanea (possibly near modern-day as-Sanamayn),[2][13][14] giving them an exemption from taxation.[15] This settlement, led by the family of Zamaris, was tasked with protecting the people of Batanea from Trachonite brigands and ensuring the safety of Jewish pilgrims traveling from Babylonia to Jerusalem.[14][16] According to Josephus, these troops were accompanied by settlers from various places who were dedicated to the "ta patria of the Jews".[17] With Herod's death in 4 BCE, Trachonitis was given to his son Philip the Tetrarch. After the latter's death, circa 34 CE, the area was incorporated into the province of Syria.[10]

During the Roman era, Trachonitis' inhabitants gradually became settled and gained exemption from taxation.[2] Under emperor Trajan, the region was transferred to the province of Arabia.[9] The Romans built a road that passed through the center of Trachonitis and connected with the Roman road system in Syria.[2] Several towns and villages sprang up in Trachonitis between the 1st and 4th centuries AD.[2] Many of these settlements had theaters, colonnades and temples.[2] There are almost twenty sites in the Lajat that contain ruins and inscriptions from the Roman period, including Phillipopolis (modern-day Shahba) and Sha'ara (ancient name unknown).[2] The town of Zorava (modern-day Izra') was the political center of Trachonitis and its earliest inhabitants were Nabatean Arabs.[19] The main Nabatean tribes of the town were the Sammenoi and the Migdalenoi (migrants from nearby al-Mujaydil).[19] The inhabitants practiced a Roman pagan cult as early as 161 AD.[19] In the 3rd century, they built numerous houses and baths from basaltic stone, and the town had a relatively urban character.[19]

Byzantine period

[edit]

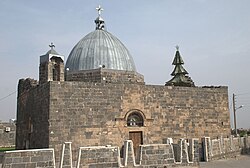

The Romans were succeeded by the Byzantine Empire in Syria during the mid-4th century AD.[2] For the following three centuries, Trachonitis saw a huge uptick in settlement and building activity.[2] Among the major Byzantine-era settlements were Bosor (modern Busra al-Harir), Zorava, Jirrin, Sur, Deir al-Juwani, Rimea, Umm al-Zaytun, Shaqra and Harran.[2][20] There are at least thirty sites in the Lajat with ruins tracing back to the Byzantine era.[2] The Byzantine era saw the expansion of Christianity in the regions surrounding the Lajat, but there archaeological evidence indicates that Christianity only affected a few Lajat villages, particularly those along its southwestern edges,[19] until the mid-6th century.[21] One of the earliest known Christian communities in Trachonitis was Sur (ancient name unknown), which had a Christian edifice dated to 458.[22]

Zorava was the cosmopolitan capital of Byzantine Trachonitis.[19] Its pagan temple was replaced by the martyrium of Saint George in 515 and the town became a bishopric in 542.[23] There are no earlier indications of a Christian presence in Zorava.[19] In addition to its Arab inhabitants, the town had a Greek-speaking community (Greek was the lingua franca of Byzantine Syria), made up mostly of army veterans, who themselves were likely ethnic Arabs recruited from the province.[23] By the mid-6th century, the Arabs of Trachonitis had largely become Christians with the cult of Saint Elijah being predominant; the cult of Saint Sergius was dominant in Trachonitis' neighboring regions.[21] In Harran, a bilingual Arabic-Greek inscription dated from 568 describes the construction of a martyrium built by a local Arab phylarch.

Middle Ages

[edit]The region's modern name "Lajah" was first recorded during the Middle Ages, and the region was only mentioned by later Arab geographers, indicating that it had likely been abandoned prior to the 13th century.[2] In the early 13th century, during Ayyubid rule, the Lajat was said to contain a "large population" and numerous villages and fields, according to Syrian geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi.[24] According to historian H. Gaube, the Lajat was likely settled by refugees from other parts of Syria due to the pressures of the Mongol invasions.[2] There are at least thirteen sites in the Lajat that contain Islamic-era ruins, most of which date to the 13th century.[2]

Ottoman period

[edit]The Lajat contained some populated places during early Ottoman rule, which began in 1517, but other than a few Christian-populated villages along its western periphery, the region was abandoned by at least the 17th century.[2]

The Lajat was settled by Druze migrants, mostly from Wadi al-Taym and Mount Lebanon, in the late 18th century and throughout the 19th century. Prior to that, the Lajat was dominated by the Sulut, a Bedouin tribe.[25] Two Druze villages, Umm al-Zaytun and Lahithah, existed in the interior of the Lajat in the early 19th century.[26] Major Druze settlement began in the aftermath of the 1860 Mount Lebanon civil war.[25] By 1862, Dama, Salakhid, Ahira, al-Kharsa, Sumayd and Harran, all in the heart of the Lajat, were settled by Druze from the Azzam, Shalghin and Hamada families, who were newcomers to the Hauran region.[26] The increasing Druze presence in Lajat led to confrontations with the Sulut tribesmen, their erstwhile allies against the Ottoman authorities, in June 1868.[27] Ismail al-Atrash led the Druze in their battles with the Sulut, while the prominent Druze clans of al-Hamdan and Bani Amer aligned with the Sulut against their chief rival, the Bani al-Atrash.[27] The Ottoman governor of Syria, Rashid Pasha, resolved to end the war, and mediated an agreement stipulating a total Druze withdrawal from Lajat.[27]

Nonetheless, Druze habitation continued and was principally concentrated on the Lajat's eastern edge and its southern interior, which bordered the Druze heartland of Jabal Hauran.[26] In 1867, the Azzam and Halabi families established the villages al-Zabayer and al-Surah al-Saghirah, both situated at the eastern edge of Lajat, respectively.[26] Between then and 1883, the Murshid family settled Lubayn, the Abu Hassun settled Jurayn and the Shalghin settled al-Majadil.[26] Along the Lajat's eastern edge, the Halabi and Bani Amer families settled Jadaya, al-Matunah, Dhakir, Khalkhalah, Umm Haratayn, Hazim and al-Surah al-Kabirah.[26] Druze activity in the Lajat's northeastern slopes regressed because of the scarcity of water and arable land, but the villages of al-Salmiyah, Huqf, Buthaynah, Burk, Arraja, Umm Dabib, al-Tayyibah and al-Ramah were established there mostly by the Bani Amer, but also by the Bani al-Atrash, al-Ghanim and al-Qal'ani clans between 1862 and 1883.[26]

Modern period

[edit]In the early 20th century, the cultivated areas of the Lajat were mostly located in its western and southwestern parts, where soil was cleared of stone and nutrient rich.[5] Wheat and barley were grown in small quantities, and in the vicinity of some villages were olive, apricot and pear trees; other than that, the region was treeless. Other vegetation included several patches of wild flowers throughout narrow cracks between the rocks of the Lajat.[28] Lajat was designated a World Biosphere reserve by UNESCO in 2009.

Biblical references

[edit]An extremely rugged region, sixty walled cities were on the island, which was ruled over by Og at the time of the Israelite conquest (Deuteronomy 3:4; 1 Kings 4:13). Later, Lajat, in Bashan, was one of Solomon's commissariat districts.[29] In Luke's Gospel, the region was called Trachonitis ("the rugged region") (Luke 3:1). This region formed part of Herod Philip's tetrarchy - it is only referred to once, in the phrase tes Itouraias kai Trachbnitidos choras, literally, "of the Iturean and Trachonian region".

- Here "sixty walled cities are still traceable in a space of 308 square miles. The architecture is ponderous and massive. Solid walls 4 feet thick, and stones on one another without cement; the roofs enormous slabs of basaltic rock, like iron; the doors and gates are of stone 18 inches thick, secured by ponderous bars. The land bears still the appearance of having been called the 'land of giants' under the giant Og."

- "I have more than once entered a deserted city in the evening, taken possession of a comfortable house, and spent the night in peace. Many of the houses in the ancient cities of Bashan are perfect, as if only finished yesterday. The walls are sound, the roofs unbroken, and even the window-shutters in their places. These ancient cities of Bashan probably contain the very oldest specimens of domestic architecture in the world" (Porter, 1867).

Population

[edit]Most of the inhabited areas of the Lajat are along its fringes, with only a few scattered villages in the interior. The interior villages lay in relatively stone-less depressions.[2] Most villages were built among the Lajat's ancient ruins.[7] Historically, the population of the Lajat consisted of nomadic and semi-nomadic Bedouin tribesmen, peasants from the Hauran plain who occasionally used it as a refuge, and beginning in the 19th century, Druze from Jabal al-Druze who settled it and/or occasionally used it for refuge or to exploit resources.[3] The Lajat was also used as a grazing area for sheep, goats and camels.[3]

By the early 20th century, about 5,000 semi-nomadic Bedouin from the Sulut tribe and a smaller population of Bedouin from the Fahsa tribe inhabited the Lajat.[7] Alongside them were about 10,000 Druze peasants who lived along the eastern and southeastern edges and to a lesser extent in the interior.[7]

Populated places in the Lajat

[edit]| Name | District | Population (2004)[30] | Religious makeup | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Ariqah | Shahba | 3,798 | Druze | Interior |

| Asim | Izra | 821 | Muslim | Interior |

| Braykah | Shahba | 1,055 | Druze | Eastern edge |

| Burraq | As-Sanamayn | 1,799 | Druze | Interior |

| Busra al-Harir | Izra | 13,315 | Muslim | Southern edge |

| Dama | Shahba | 1,799 | Druze | Interior |

| Dhakir | Shahba | 519 | Druze | Eastern edge |

| Ad-Duwayri | As-Suwayda | 950 | Druze | Southern edge |

| Harran | Shahba | 1,523 | Druze | Interior |

| Hazm | Shahba | 858 | Druze | Eastern edge |

| Izra | Izra | 19,158 | Melkite Christian | Southern edge |

| Jaddil | Izra | 1,508 | Muslim | Interior |

| Jirrin | Shahba | 507 | Druze | Interior |

| Khabab | As-Sanamayn | 1,508 | Melkite Christian | Western edge |

| Khalkhalah | Shahba | 2,268 | Druze | Eastern edge |

| Al-Kharsah | Shahba | 547 | Druze | Interior |

| Lahithah | Shahba | 2,275 | Druze | Eastern edge |

| Lubayn | Shahba | 1,730 | Druze | Interior |

| Al-Matunah | Shahba | 1,366 | Druze | Eastern edge |

| Al-Mujaydil | Izra | 598 | ? | Western edge |

| Al-Masmiyah | As-Sanamayn | 1,498 | Melkite Christian | Interior |

| Najran | As-Suwayda | 2,955 | Druze | Southern edge |

| Qarrasa | As-Suwayda | 638 | Druze | Southern edge |

| Rimat al-Luhf | As-Suwayda | 1,925 | Druze | Southern edge |

| Rudaymat al-Liwa | Shahba | 1,001 | Druze | Eastern edge |

| Salakhid | Shahba | 950 | Druze | Interior |

| Sha'rah | As-Sanamayn | 1,508 | Muslim | Interior |

| Shahba | Shahba | 13,360 | Druze | Eastern edge |

| Sumayd | Shahba | 853 | Druze | Interior |

| Sur | Izra | 924 | Muslim | Interior |

| As-Surah al-Kabirah | Shahba | 885 | Druze | Eastern edge |

| As-Surah as-Saghirah | Shahba | 1,517 | Druze | Eastern edge |

| Umm Haratayn | Shahba | 574 | Druze | Eastern edge |

| Umm az-Zaytun | Shahba | 1,913 | Druze | Eastern edge |

| Waqm | Shahba | 429 | Druze | Interior |

Maps

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Deuteronomy 3:13–14, a biblical word that is translated by Onkelos as טְרָכוֹנָא = Trachona. For a discussion of whether the Hebrew lexeme ארגב is a common noun or proper noun, see Reuven Chaim Klein. "Who or What Is Argov? A Philological Survey of a Difficult Lexeme". Ḥakirah. doi:10.17613/7qw28-qkz54. ISSN 1532-1290.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Gaube 1982, p. 593.

- ^ a b c d e Lewis, p. 631.

- ^ Voysey 1920, p. 206.

- ^ a b c d e Voysey 1920, p. 208.

- ^ Voysey 1920, pp. 208−209.

- ^ a b c d Voysey, p. 209.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, xv, x, i; The Jewish War, i, xx, 4

- ^ a b Jones, A. H. M. (1931). "The Urbanization of the Ituraean Principality". The Journal of Roman Studies. 21 (2): 266–268. doi:10.2307/296522. ISSN 1753-528X.

- ^ a b Rogers, Guy MacLean (2021). For the Freedom of Zion: the Great Revolt of Jews against Romans, 66-74 CE. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 544. ISBN 978-0-300-24813-5.

- ^ Syon, Danny (2014). Gamla III: The Shmarya Gutmann Excavations, 1976–1989. Finds and Studies (PDF). Vol. 1. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority Reports, No. 56. ISBN 978-965-406-503-0. p. 8 "Herod’s activities in Northern Transjordan consisted mainly of occasionally fighting the Nabateans and of efforts to eradicate the bands of brigands in the Trachon (Trachonitis), first by settling Idumeans in the region, and later, Babylonian Jews."

- ^ Shatzman, Israel (1994). "The Limits of Empire: Review Article". Israel Exploration Journal. 44 (1/2): 134–135. ISSN 0021-2059.

- ^ a b Saddington, Denis B. (2009-01-01), "Client Kings Armies Under Augustus: The Case Of Herod", Herod and Augustus, Brill, p. 317, doi:10.1163/ej.9789004165465.i-418.81, ISBN 978-90-474-4309-4, retrieved 2024-06-15

- ^ a b c Applebaum, Shimon (1989-01-01), "The Troopers of Zamaris", Judaea in Hellenistic and Roman Times, Brill, p. 47, ISBN 978-90-04-66664-1, retrieved 2024-06-15

- ^ Dauphin, Claudine M. (1982). "Jewish and Christian Communities in the Roman and Byzantine Gaulanitis : A Study of Evidence from Archaeological Surveys". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 114 (2): 129–130. doi:10.1179/peq.1982.114.2.129. ISSN 0031-0328.

The Roman Emperor Augustus sought to contain this source of unrest by annexing the neighbouring districts of Batanea, Trachonitis and Auranitis. These he placed under Herod's administration in 23 BCE, and in 20 BCE he added the area of Gaulanitis itself, the city of Pane as and the Ulatha Valley, all of which had until then been ruled by the kingdom of Iturea. To implement this new rule and maintain the peace, Herod initiated an extensive programme of paramilitary settlement. He transferred 3,000 Idumeans to the area of Trachonitis and 500 families of Jewish soldiers to Batanea, rewarding them by exemption from taxation (Ant. XVII, 2, 1-3).

- ^ Cohen, Getzel (2015-01-01), "9 Travel between Palestine and Mesopotamia during the Hellenistic and Roman Periods: A Preliminary Study", The Archaeology and Material Culture of the Babylonian Talmud, Brill, p. 206, doi:10.1163/9789004304895_011, ISBN 978-90-04-30489-5, retrieved 2024-06-15

- ^ Goodblatt, David, ed. (2006), "Theoretical Considerations: Nationalism and Ethnicity in Antiquity", Elements of Ancient Jewish Nationalism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 26, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511499067.002, ISBN 978-0-521-86202-8, retrieved 2024-06-14

- ^ Maurice Sartre, "Paolo CIMADOMO, The Southern Levant During the First Centuries of Roman Rule (64 BC-135 AD). Interweaving Local Cultures", Syria [Online], Book reviews, Online since 14 September 2021, connection on 16 September 2021. doi:10.4000/syria.11213, journals

.openedition , accessed 25 February 2022..org /syria /11213 - ^ a b c d e f g Trombley, p. 359.

- ^ Trombley, pp. 365–371.

- ^ a b Trombley, p. 367.

- ^ Trombley, p. 366.

- ^ a b Trombley, pp. 359–360.

- ^ Le Strange, Guy (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Alexander P. Watt. p. 492.

- ^ a b Firro 1992, p. 173.

- ^ a b c d e f g Firro 1992, p. 175.

- ^ a b c Firro 1992, p. 174.

- ^ Voysey 1920, p. 211.

- ^ 1 Kings 4:13

- ^ 2004 census figures from the Central Bureau of Statistics (Syria).

Bibliography

[edit]- Gaube, H. (1982). "Ladja'". In Bosworth, C. E.; Donzel, E. van; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Islam, Volume 5, Fasicules 87-88: New Edition. Leiden: Brill. p. 593.

- Firro, Kais (1992). A History of the Druzes. Vol. 1. BRILL. p. 175. ISBN 9004094377.

- Lewis, Norman N. (1995). "The Laja' in the Last Century of Ottoman Rule". In Panzac, Daniel (ed.). Histoire économique et sociale de l'Empire ottoman et de la Turquie (1326-1960). Peeters Publishers. ISBN 90-6831-799-7.

- Porter, Josias Leslie. The Giant Cities of Bashan and Syria's Holy Places, New York: T. Nelson, 1867. [1]

- Voysey, Annesley (September 1920). "Notes on the Laja". The Geographical Journal. 56 (3): 206–213. doi:10.2307/1781537. JSTOR 1781537.

External links

[edit]- Ewing, W. "Definition for ARGOB (2)", International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, 1915.

- TRACHONITIS