Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2018) |

Ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometry (UV–Vis or UV-VIS)[1][2][3] refers to absorption spectroscopy or reflectance spectroscopy in part of the ultraviolet and the full, adjacent visible regions of the electromagnetic spectrum.[2] Being relatively inexpensive and easily implemented, this methodology is widely used in diverse applied and fundamental applications. The only requirement is that the sample absorb in the UV–Vis region, i.e. be a chromophore. Absorption spectroscopy is complementary to fluorescence spectroscopy. Parameters of interest, besides the wavelength of measurement, are absorbance (A) or transmittance (%T) or reflectance (%R), and its change with time.[4][5]

A UV–Vis spectrophotometer is an analytical instrument that measures the amount of ultraviolet (UV) and visible light that is absorbed by a sample. It is a widely used technique in chemistry, biochemistry, and other fields, to identify and quantify compounds in a variety of samples.[6]

UV–Vis spectrophotometers work by passing a beam of light through the sample and measuring the amount of light that is absorbed at each wavelength. The amount of light absorbed is proportional to the concentration of the absorbing compound in the sample.

Optical transitions

[edit]Most molecules and ions absorb energy in the ultraviolet or visible range, i.e., they are chromophores. The absorbed photon excites an electron in the chromophore to higher energy molecular orbitals, giving rise to an excited state.[7] For organic chromophores, four possible types of transitions are assumed: π–π*, n–π*, σ–σ*, and n–σ*. Transition metal complexes are often colored (i.e., absorb visible light) owing to the presence of multiple electronic states associated with incompletely filled d orbitals.[5]

Applications

[edit]

UV–Vis can be used to monitor structural changes in DNA.[8]

UV–Vis spectroscopy is routinely used in analytical chemistry for the quantitative determination of diverse analytes or sample, such as transition metal ions, highly conjugated organic compounds, and biological macromolecules. Spectroscopic analysis is commonly carried out in solutions but solids and gases may also be studied.

- Organic compounds, especially those with a high degree of conjugation, also absorb light in the UV or visible regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. The solvents for these determinations are often water for water-soluble compounds, or ethanol for organic-soluble compounds. (Organic solvents may have significant UV absorption; not all solvents are suitable for use in UV spectroscopy. Ethanol absorbs very weakly at most wavelengths.) Solvent polarity and pH can affect the absorption spectrum of an organic compound. Tyrosine, for example, increases in absorption maxima and molar extinction coefficient when pH increases from 6 to 13 or when solvent polarity decreases.

- While charge transfer complexes also give rise to colors, the colors are often too intense to be used for quantitative measurement.

The Beer–Lambert law states that the absorbance of a solution is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing species in the solution and the path length.[9] Thus, for a fixed path length, UV–Vis spectroscopy can be used to determine the concentration of the absorber in a solution. It is necessary to know how quickly the absorbance changes with concentration. This can be taken from references (tables of molar extinction coefficients), or more accurately, determined from a calibration curve.

A UV–Vis spectrophotometer may be used as a detector for HPLC. The presence of an analyte gives a response assumed to be proportional to the concentration. For accurate results, the instrument's response to the analyte in the unknown should be compared with the response to a standard; this is very similar to the use of calibration curves. The response (e.g., peak height) for a particular concentration is known as the response factor.

The wavelengths of absorption peaks can be correlated with the types of bonds in a given molecule and are valuable in determining the functional groups within a molecule. The Woodward–Fieser rules, for instance, are a set of empirical observations used to predict λmax, the wavelength of the most intense UV–Vis absorption, for conjugated organic compounds such as dienes and ketones. The spectrum alone is not, however, a specific test for any given sample. The nature of the solvent, the pH of the solution, temperature, high electrolyte concentrations, and the presence of interfering substances can influence the absorption spectrum. Experimental variations such as the slit width (effective bandwidth) of the spectrophotometer will also alter the spectrum. To apply UV–Vis spectroscopy to analysis, these variables must be controlled or accounted for in order to identify the substances present.[10]

The method is most often used in a quantitative way to determine concentrations of an absorbing species in solution, using the Beer–Lambert law:[11]

- ,

where A is the measured absorbance (formally dimensionless but generally reported in absorbance units (AU)[12]), is the intensity of the incident light at a given wavelength, is the transmitted intensity, L the path length through the sample, and c the concentration of the absorbing species. For each species and wavelength, ε is a constant known as the molar absorptivity or extinction coefficient. This constant is a fundamental molecular property in a given solvent, at a particular temperature and pressure, and has units of .

The absorbance and extinction ε are sometimes defined in terms of the natural logarithm instead of the base-10 logarithm.

The Beer–Lambert law is useful for characterizing many compounds but does not hold as a universal relationship for the concentration and absorption of all substances. A 2nd order polynomial relationship between absorption and concentration is sometimes encountered[13] for very large, complex molecules such as organic dyes (xylenol orange or neutral red, for example).[14][15]

UV–Vis spectroscopy is also used in the semiconductor industry to measure the thickness and optical properties of thin films on a wafer. UV–Vis spectrometers are used to measure the reflectance of light, and can be analyzed via the Forouhi–Bloomer dispersion equations to determine the index of refraction () and the extinction coefficient () of a given film across the measured spectral range.[16]

Practical considerations

[edit]The Beer–Lambert law has implicit assumptions that must be met experimentally for it to apply; otherwise there is a possibility of deviations from the law.[14] For instance, the chemical makeup and physical environment of the sample can alter its extinction coefficient. The chemical and physical conditions of a test sample therefore must match reference measurements for conclusions to be valid. Worldwide, pharmacopoeias such as the American (USP) and European (Ph. Eur.) pharmacopeias demand that spectrophotometers perform according to strict regulatory requirements encompassing factors such as stray light[17] and wavelength accuracy.[18]

Spectral bandwidth

[edit]Spectral bandwidth of a spectrophotometer is the range of wavelengths that the instrument transmits through a sample at a given time.[19] It is determined by the light source, the monochromator, its physical slit-width and optical dispersion and the detector of the spectrophotometer. The spectral bandwidth affects the resolution and accuracy of the measurement. A narrower spectral bandwidth provides higher resolution and accuracy, but also requires more time and energy to scan the entire spectrum. A wider spectral bandwidth allows for faster and easier scanning, but may result in lower resolution and accuracy, especially for samples with overlapping absorption peaks. Therefore, choosing an appropriate spectral bandwidth is important for obtaining reliable and precise results.

It is important to have a monochromatic source of radiation for the light incident on the sample cell to enhance the linearity of the response.[14] The closer the bandwidth is to be monochromatic (transmitting unit of wavelength) the more linear will be the response. The spectral bandwidth is measured as the number of wavelengths transmitted at half the maximum intensity of the light leaving the monochromator.

The best spectral bandwidth achievable is a specification of the UV spectrophotometer, and it characterizes how monochromatic the incident light can be. If this bandwidth is comparable to (or more than) the width of the absorption peak of the sample component, then the measured extinction coefficient will not be accurate. In reference measurements, the instrument bandwidth (bandwidth of the incident light) is kept below the width of the spectral peaks. When a test material is being measured, the bandwidth of the incident light should also be sufficiently narrow. Reducing the spectral bandwidth reduces the energy passed to the detector and will, therefore, require a longer measurement time to achieve the same signal to noise ratio.

Wavelength error

[edit]The extinction coefficient of an analyte in solution changes gradually with wavelength. A peak (a wavelength where the absorbance reaches a maximum) in the absorbance curve vs wavelength, i.e. the UV–VIS spectrum, is where the rate of change of absorbance with wavelength is the lowest.[14] Therefore, quantitative measurements of a solute are usually conducted, using a wavelength around the absorbance peak, to minimize inaccuracies produced by errors in wavelength, due to the change of extinction coefficient with wavelength.

Stray light

[edit]Stray light[20] in a UV spectrophotometer is any light that reaches its detector that is not of the wavelength selected by the monochromator. This can be caused, for instance, by scattering of light within the instrument, or by reflections from optical surfaces.

Stray light can cause significant errors in absorbance measurements, especially at high absorbances, because the stray light will be added to the signal detected by the detector, even though it is not part of the actually selected wavelength. The result is that the measured and reported absorbance will be lower than the actual absorbance of the sample.

The stray light is an important factor, as it determines the purity of the light used for the analysis. The most important factor affecting it is the stray light level of the monochromator.[14]

Typically a detector used in a UV–VIS spectrophotometer is broadband; it responds to all the light that reaches it. If a significant amount of the light passed through the sample contains wavelengths that have much lower extinction coefficients than the nominal one, the instrument will report an incorrectly low absorbance. Any instrument will reach a point where an increase in sample concentration will not result in an increase in the reported absorbance, because the detector is simply responding to the stray light. In practice the concentration of the sample or the optical path length must be adjusted to place the unknown absorbance within a range that is valid for the instrument. Sometimes an empirical calibration function is developed, using known concentrations of the sample, to allow measurements into the region where the instrument is becoming non-linear.

As a rough guide, an instrument with a single monochromator would typically have a stray light level corresponding to about 3 Absorbance Units (AU), which would make measurements above about 2 AU problematic. A more complex instrument with a double monochromator would have a stray light level corresponding to about 6 AU, which would therefore allow measuring a much wider absorbance range.

Deviations from the Beer–Lambert law

[edit]At sufficiently high concentrations, the absorption bands will saturate and show absorption flattening. The absorption peak appears to flatten because close to 100% of the light is already being absorbed. The concentration at which this occurs depends on the particular compound being measured. One test that can be used to test for this effect is to vary the path length of the measurement. In the Beer–Lambert law, varying concentration and path length has an equivalent effect—diluting a solution by a factor of 10 has the same effect as shortening the path length by a factor of 10. If cells of different path lengths are available, testing if this relationship holds true is one way to judge if absorption flattening is occurring.

Solutions that are not homogeneous can show deviations from the Beer–Lambert law because of the phenomenon of absorption flattening. This can happen, for instance, where the absorbing substance is located within suspended particles.[21][22] The deviations will be most noticeable under conditions of low concentration and high absorbance. The last reference describes a way to correct for this deviation.

Some solutions, like copper(II) chloride in water, change visually at a certain concentration because of changed conditions around the colored ion (the divalent copper ion). For copper(II) chloride it means a shift from blue to green,[23] which would mean that monochromatic measurements would deviate from the Beer–Lambert law.

Measurement uncertainty sources

[edit]The above factors contribute to the measurement uncertainty of the results obtained with UV–Vis spectrophotometry. If UV–Vis spectrophotometry is used in quantitative chemical analysis then the results are additionally affected by uncertainty sources arising from the nature of the compounds and/or solutions that are measured. These include spectral interferences caused by absorption band overlap, fading of the color of the absorbing species (caused by decomposition or reaction) and possible composition mismatch between the sample and the calibration solution.[24]

Ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometer

[edit]The instrument used in ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy is called a UV–Vis spectrophotometer. It measures the intensity of light after passing through a sample (), and compares it to the intensity of light before it passes through the sample (). The ratio is called the transmittance, and is usually expressed as a percentage (%T). The absorbance, , is based on the transmittance:

The UV–visible spectrophotometer can also be configured to measure reflectance. In this case, the spectrophotometer measures the intensity of light reflected from a sample (), and compares it to the intensity of light reflected from a reference material () (such as a white tile). The ratio is called the reflectance, and is usually expressed as a percentage (%R).

The basic parts of a spectrophotometer are a light source, a holder for the sample, a diffraction grating or a prism as a monochromator to separate the different wavelengths of light, and a detector. The radiation source is often a tungsten filament (300–2500 nm), a deuterium arc lamp, which is continuous over the ultraviolet region (190–400 nm), a xenon arc lamp, which is continuous from 160 to 2,000 nm; or more recently, light emitting diodes (LED)[4] for the visible wavelengths. The detector is typically a photomultiplier tube, a photodiode, a photodiode array or a charge-coupled device (CCD). Single photodiode detectors and photomultiplier tubes are used with scanning monochromators, which filter the light so that only light of a single wavelength reaches the detector at one time. The scanning monochromator moves the diffraction grating to "step-through" each wavelength so that its intensity may be measured as a function of wavelength. Fixed monochromators are used with CCDs and photodiode arrays. As both of these devices consist of many detectors grouped into one or two dimensional arrays, they are able to collect light of different wavelengths on different pixels or groups of pixels simultaneously.

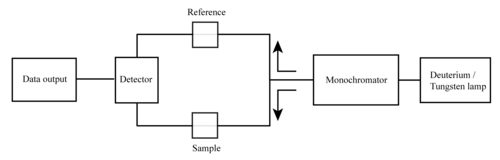

A spectrophotometer can be either single beam or double beam. In a single beam instrument (such as the Spectronic 20), all of the light passes through the sample cell. must be measured by removing the sample. This was the earliest design and is still in common use in both teaching and industrial labs.

In a double-beam instrument, the light is split into two beams before it reaches the sample. One beam is used as the reference; the other beam passes through the sample. The reference beam intensity is taken as 100% Transmission (or 0 Absorbance), and the measurement displayed is the ratio of the two beam intensities. Some double-beam instruments have two detectors (photodiodes), and the sample and reference beam are measured at the same time. In other instruments, the two beams pass through a beam chopper, which blocks one beam at a time. The detector alternates between measuring the sample beam and the reference beam in synchronism with the chopper. There may also be one or more dark intervals in the chopper cycle. In this case, the measured beam intensities may be corrected by subtracting the intensity measured in the dark interval before the ratio is taken.

In a single-beam instrument, the cuvette containing only a solvent has to be measured first. Mettler Toledo developed a single beam array spectrophotometer that allows fast and accurate measurements over the UV–Vis range. The light source consists of a Xenon flash lamp for the ultraviolet (UV) as well as for the visible (VIS) and near-infrared wavelength regions covering a spectral range from 190 up to 1100 nm. The lamp flashes are focused on a glass fiber which drives the beam of light onto a cuvette containing the sample solution. The beam passes through the sample and specific wavelengths are absorbed by the sample components. The remaining light is collected after the cuvette by a glass fiber and driven into a spectrograph. The spectrograph consists of a diffraction grating that separates the light into the different wavelengths, and a CCD sensor to record the data, respectively. The whole spectrum is thus simultaneously measured, allowing for fast recording.[25]

Samples for UV–Vis spectrophotometry are most often liquids, although the absorbance of gases and even of solids can also be measured. Samples are typically placed in a transparent cell, known as a cuvette. Cuvettes are typically rectangular in shape, commonly with an internal width of 1 cm. (This width becomes the path length, , in the Beer–Lambert law.) Test tubes can also be used as cuvettes in some instruments. The type of sample container used must allow radiation to pass over the spectral region of interest. The most widely applicable cuvettes are made of high-quality fused silica or quartz glass because these are transparent throughout the UV, visible and near infrared regions. Glass and plastic cuvettes are also common, although glass and most plastics absorb in the UV, which limits their usefulness to visible wavelengths.[4]

Specialized instruments have also been made. These include attaching spectrophotometers to telescopes to measure the spectra of astronomical features. UV–visible microspectrophotometers consist of a UV–visible microscope integrated with a UV–visible spectrophotometer.

A complete spectrum of the absorption at all wavelengths of interest can often be produced directly by a more sophisticated spectrophotometer. In simpler instruments the absorption is determined one wavelength at a time and then compiled into a spectrum by the operator. By removing the concentration dependence, the extinction coefficient (ε) can be determined as a function of wavelength.

Microspectrophotometry

[edit]UV–visible spectroscopy of microscopic samples is done by integrating an optical microscope with UV–visible optics, white light sources, a monochromator, and a sensitive detector such as a charge-coupled device (CCD) or photomultiplier tube (PMT). As only a single optical path is available, these are single beam instruments. Modern instruments are capable of measuring UV–visible spectra in both reflectance and transmission of micron-scale sampling areas. The advantages of using such instruments is that they are able to measure microscopic samples but are also able to measure the spectra of larger samples with high spatial resolution. As such, they are used in the forensic laboratory to analyze the dyes and pigments in individual textile fibers,[26] microscopic paint chips[27] and the color of glass fragments. They are also used in materials science and biological research and for determining the energy content of coal and petroleum source rock by measuring the vitrinite reflectance. Microspectrophotometers are used in the semiconductor and micro-optics industries for monitoring the thickness of thin films after they have been deposited. In the semiconductor industry, they are used because the critical dimensions of circuitry is microscopic. A typical test of a semiconductor wafer would entail the acquisition of spectra from many points on a patterned or unpatterned wafer. The thickness of the deposited films may be calculated from the interference pattern of the spectra. In addition, ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometry can be used to determine the thickness, along with the refractive index and extinction coefficient of thin films.[16] A map of the film thickness across the entire wafer can then be generated and used for quality control purposes.[28]

Additional applications

[edit]UV–Vis can be applied to characterize the rate of a chemical reaction. Illustrative is the conversion of the yellow-orange and blue isomers of mercury dithizonate. This method of analysis relies on the fact that concentration is linearly proportional to concentration. In the same approach allows determination of equilibria between chromophores.[29][30]

From the spectrum of burning gases, it is possible to determine a chemical composition of a fuel, temperature of gases, and air-fuel ratio.[31]

See also

[edit]- Applied spectroscopy

- Benesi–Hildebrand method

- Color – Vis spectroscopy with the human eye

- Charge modulation spectroscopy

- DU spectrophotometer – first UV–Vis instrument

- Fourier-transform spectroscopy

- Infrared spectroscopy and Raman spectroscopy are other common spectroscopic techniques, usually used to obtain information about the structure of compounds or to identify compounds. Both are forms of vibrational spectroscopy.

- Isosbestic point – a wavelength where absorption does not change as the reaction proceeds. Important in kinetics measurements as a control.

- Near-infrared spectroscopy

- Rotational spectroscopy

- Slope spectroscopy

- Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy of stereoisomers

- Vibrational spectroscopy

References

[edit]- ^ Cole, Kenneth; Levine, Barry S. (2020), Levine, Barry S.; Kerrigan, Sarah (eds.), "Ultraviolet–Visible Spectrophotometry", Principles of Forensic Toxicology, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 127–134, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-42917-1_10, ISBN 978-3-030-42917-1

- ^ a b Vitha, Mark F. (2018). "Chapter 2". Spectroscopy: principles and instrumentation. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-43664-5.

- ^ Edwards, Alison A.; Alexander, Bruce D. (1 January 2017), "UV–Visible Absorption Spectroscopy, Organic Applications", in Lindon, John C.; Tranter, George E.; Koppenaal, David W. (eds.), Encyclopedia of Spectroscopy and Spectrometry (Third Edition), Oxford: Academic Press, pp. 511–519, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-803224-4.00013-3, ISBN 978-0-12-803224-4, retrieved 19 October 2023

- ^ a b c Skoog, Douglas A.; Holler, F. James; Crouch, Stanley R. (2007). Principles of Instrumental Analysis (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole. pp. 169–173. ISBN 978-0-495-01201-6.[dead link]

- ^ a b R. S. Drago (1992). Physical Methods for Chemists, 2nd Edition. W. B. Saunders. ISBN 0-03-075176-4.

- ^ Franca, Adriana S.; Nollet, Leo M.L. (2017). Spectroscopic Methods in Food Analysis. CRC Press. p. 664.

- ^ Metha, Akul (13 December 2011). "Principle". PharmaXChange.info.

- ^ Carroll, Gregory T.; Dowling, Reed C.; Kirschman, David L.; Masthay, Mark B.; Mammana, Angela (2023). "Intrinsic fluorescence of UV-irradiated DNA". Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry. 437 114484. doi:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2022.114484. S2CID 254622477.

- ^ Metha, Akul (22 April 2012). "Derivation of Beer–Lambert Law". PharmaXChange.info.

- ^ Misra, Prabhakar; Dubinskii, Mark, eds. (2002). Ultraviolet Spectroscopy and UV Lasers. New York: Marcel Dekker. ISBN 978-0-8247-0668-5.[page needed]

- ^ "The Beer–Lambert Law". Chemistry LibreTexts. 3 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ Historically, the term "Optical Density" (OD) was used instead of AU. But it is also worth noting that what is usually measured is percent transmission (%T), a linear ratio, which is converted to the logarithm by the instrument for presentation.

- ^ Bozdoğan, Abdürrezzak E. (1 November 2022). "Polynomial Equations based on Bouguer–Lambert and Beer Laws for Deviations from Linearity and Absorption Flattening". Journal of Analytical Chemistry. 77 (11): 1426–1432. doi:10.1134/S1061934822110028. ISSN 1608-3199. S2CID 253463022.

- ^ a b c d e Metha, Akul (14 May 2012). "Limitations and Deviations of Beer–Lambert Law". PharmaXChange.info.

- ^ Cinar, Mehmet; Coruh, Ali; Karabacak, Mehmet (25 March 2014). "A comparative study of selected disperse azo dye derivatives based on spectroscopic (FT-IR, NMR and UV–Vis) and nonlinear optical behaviors". Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 122: 682–689. Bibcode:2014AcSpA.122..682C. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2013.11.106. ISSN 1386-1425. PMID 24345608.

- ^ a b Löper, Philipp; Stuckelberger, Michael; Niesen, Bjoern; Werner, Jérémie; Filipič, Miha; Moon, Soo-Jin; Yum, Jun-Ho; Topič, Marko; De Wolf, Stefaan; Ballif, Christophe (2015). "Complex Refractive Index Spectra of CH3NH3PbI3 Perovskite Thin Films Determined by Spectroscopic Ellipsometry and Spectrophotometry" (PDF). The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 6 (1): 66–71. doi:10.1021/jz502471h. PMID 26263093. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ "Stray Light and Performance Verification".

- ^ "Wavelength Accuracy in UV/VIS Spectrophotometry". Archived from the original on 9 August 2024. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ "Persee PG Scientific Inc. – New-UV FAQ: Spectral Band Width". www.perseena.com. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018.

- ^ "What is Stray light and how it is monitored?". 12 June 2015.

- ^ Berberan-Santos, M. N. (September 1990). "Beer's law revisited". Journal of Chemical Education. 67 (9): 757. Bibcode:1990JChEd..67..757B. doi:10.1021/ed067p757.

- ^ Wittung, Pernilla; Kajanus, Johan; Kubista, Mikael; Malmström, Bo G. (19 September 1994). "Absorption flattening in the optical spectra of liposome-entrapped substances". FEBS Letters. 352 (1): 37–40. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(94)00912-0. PMID 7925937. S2CID 11419856.

- ^ Ansell, S; Tromp, R H; Neilson, G W (20 February 1995). "The solute and aquaion structure in a concentrated aqueous solution of copper(II) chloride". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 7 (8): 1513–1524. Bibcode:1995JPCM....7.1513A. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/7/8/002. S2CID 250898349.

- ^ Sooväli, L.; Rõõm, E.-I.; Kütt, A.; et al. (2006). "Uncertainty sources in UV–Vis spectrophotometric measurement". Accreditation and Quality Assurance. 11 (5): 246–255. doi:10.1007/s00769-006-0124-x. S2CID 94520012.

- ^ "Spectrophotometry Applications and Fundamentals". www.mt.com. Mettler Toledo International Inc. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ Forensic Fiber Examination Guidelines, Scientific Working Group-Materials, 1999, http://www.swgmat.org/fiber.htm Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Standard Guide for Microspectrophotometry and Color Measurement in Forensic Paint Analysis, Scientific Working Group-Materials, 1999, http://www.swgmat.org/paint.htm Archived 21 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Horie, M.; Fujiwara, N.; Kokubo, M.; Kondo, N. (1994). "Spectroscopic thin film thickness measurement system for semiconductor industries". Conference Proceedings. 10th Anniversary. IMTC/94. Advanced Technologies in I & M. 1994 IEEE Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (Cat. No.94CH3424-9). pp. 677–682. doi:10.1109/IMTC.1994.352008. ISBN 0-7803-1880-3. S2CID 110637259.

- ^ Sertova, N.; Petkov, I.; Nunzi, J.-M. (June 2000). "Photochromism of mercury(II) dithizonate in solution". Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry. 134 (3): 163–168. doi:10.1016/s1010-6030(00)00267-7.

- ^ UC Davis (2 October 2013). "The Rate Law". ChemWiki. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Mekhrengin, M.V.; Meshkovskii, I.K.; Tashkinov, V.A.; Guryev, V.I.; Sukhinets, A.V.; Smirnov, D.S. (June 2019). "Multispectral pyrometer for high temperature measurements inside combustion chamber of gas turbine engines". Measurement. 139: 355–360. Bibcode:2019Meas..139..355M. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2019.02.084. S2CID 116260472.