Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Laser pointer

View on Wikipedia

A laser pointer or laser pen is a (typically battery-powered) handheld device that uses a laser diode to emit a narrow low-power visible laser beam (i.e. coherent light) to highlight something of interest with a small bright colored spot.

The small width of the beam and the low power of typical laser pointers make the beam itself invisible in a clean atmosphere, only showing a point of light when striking an opaque surface. Laser pointers can project a visible beam via scattering from dust particles or water droplets along the beam path. Higher-power and higher-frequency green or blue lasers may produce a beam visible even in clean air because of Rayleigh scattering from air molecules, especially when viewed in moderately-to-dimly lit conditions. The intensity of such scattering increases when these beams are viewed from angles near the beam axis. Such pointers, particularly in the green-light output range, are used as astronomical object pointers for teaching purposes.

Laser pointers make a potent signaling tool, even in daylight, and are able to produce a bright signal for potential search and rescue vehicles using an inexpensive, small and lightweight device of the type that could be routinely carried in an emergency kit.

There are significant safety concerns with the use of laser pointers. Most jurisdictions have restrictions on lasers above 5 mW. If aimed at a person's eyes, laser pointers can cause temporary visual disturbances or even severe damage to vision. There are reports in the medical literature documenting permanent injury to the macula and the subsequent permanent loss of vision after laser light from a laser pointer was shone at a human's eyes. In rare cases, a dot of light from a red laser pointer may be thought to be due to a laser gunsight.[1] When pointed at aircraft at night, laser pointers may dazzle and distract pilots, and increasingly strict laws have been passed to ban this.

The low-cost availability of infrared (IR) diode laser modules of up to 1000 mW (1 watt) output has created a generation of IR-pumped, frequency doubled, green, blue, and violet diode-pumped solid-state laser pointers with visible power up to 300 mW. Because the invisible IR component in the beams of these visible lasers is difficult to filter out, and also because filtering it contributes extra heat which is difficult to dissipate in a small pocket "laser pointer" package, it is often left as a beam component in cheaper high-power pointers. This invisible IR component causes a degree of extra potential hazard in these devices when pointed at nearby objects and people.

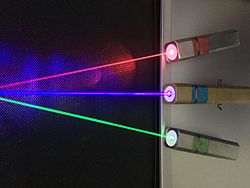

Colors and wavelengths

[edit]Early laser pointers were helium–neon (HeNe) gas lasers and generated laser radiation at 633 nanometers (nm), usually designed to produce a laser beam with an output power under 1 milliwatt (mW). The least expensive laser pointers use a deep-red laser diode near the 650 nm wavelength. Slightly more expensive ones use a red-orange 635 nm diode, more easily visible because of the greater sensitivity of the human eye at 635 nm. Other colors are possible too, with the 532 nm green laser being the most common alternative. Yellow-orange laser pointers, at 593.5 nm, later became available. In September 2005 handheld blue laser pointers at 473 nm became available. In early 2010 "Blu-ray" (actually violet) laser pointers at 405 nm went on sale.

The apparent brightness of a spot from a laser beam depends on the optical power of the laser, the reflectivity of the surface, and the chromatic response of the human eye. For the same optical power, green laser light will seem brighter than other colors, because the human eye is most sensitive at low light levels in the green region of the spectrum (wavelength 520–570 nm). Sensitivity decreases for longer (redder) and shorter (bluer) wavelengths. Additionally, the beam's brightness can be influenced by Rayleigh scattering, as shorter wavelengths such as blue and violet light are scattered more readily in the atmosphere making the beam more visible in the air.[2]

The output power of a laser pointer is usually stated in milliwatts (mW). In the U.S., lasers are classified by the American National Standards Institute[3] and Food and Drug Administration (FDA)—see Laser safety#Classification for details. Visible laser pointers (400–700 nm) operating at less than 1 mW power are Class 2 or II, and visible laser pointers operating with 1–5 mW power are Class 3A or IIIa. Class 3B or IIIb lasers generate between 5 and 500 mW; Class 4 or IV lasers generate more than 500 mW. The US FDA Code of Federal Regulations stipulates that "demonstration laser products" such as pointers must comply with applicable requirements for Class I, II, IIIA, IIIB, or IV devices.[4]

| Color | Wavelength(s) |

|---|---|

| Red | 638 nm, 650 nm, 670 nm |

| Orange | 593 nm |

| Yellow | 589 nm, 593 nm |

| Green | 532 nm, 515/520 nm |

| Blue | 450 nm, 473 nm, 488 nm |

| Violet | 405 nm |

Red

[edit]These are the simplest pointers, as laser diodes are available in these wavelengths. The pointer is most common and mostly low-powered.

The first red laser pointers released in the early 1980s were large, unwieldy devices that sold for hundreds of dollars.[5] Today, they are much smaller and less expensive. The most common wavelengths are ca. 638 and 650 nm.

Green

[edit]

High power (W) Diode Pumped Green Lasers first appeared on the market in 1996 in laser photo-coagulation, once the "green problem" was solved.[6] Much lower power (mW) green laser pointers[7] appeared on the market around 2000 and are the most common type of DPSS lasers (also called diode-pumped solid-state frequency-doubled, DPSSFD). They are more complex than standard red laser pointers, because laser diodes are not commonly available in this wavelength range. The green light is generated through a multi-step process, usually beginning with a high-power (typically 100–300 mW) infrared aluminium gallium arsenide (AlGaAs) laser diode operating at 808 nm. The 808 nm light pumps a neodymium doped crystal, usually neodymium-doped yttrium orthovanadate (Nd:YVO4) or neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG), or, less commonly, neodymium-doped yttrium lithium fluoride (Nd:YLF)), which lases deeper in the infrared at 1064 nm. This lasing action is due to an electronic transition in the fluorescent neodymium ion, Nd(III), which is present in all of these crystals.

Some green lasers operate in pulse or quasi-continuous wave (QCW) mode to reduce cooling problems and prolong battery life.

An announcement in 2009[8] of a direct green laser (which does not require doubling) promises much higher efficiencies and could foster the development of new color video projectors.

In 2012, Nichia[9] and OSRAM[10] developed and manufactured merchant high-power green laser diodes (515/520 nm), which can emit green laser directly.

Because even a low-powered green laser is visible at night through Rayleigh scattering from air molecules, this type of pointer is used by astronomers to easily point out stars and constellations. Green laser pointers can come in a variety of different output powers. The 5 mW green laser pointers (classes II and IIIa) are the safest to use, and anything more powerful is usually not necessary for pointing purposes, since the beam is still visible in dark lighting conditions.

Blue

[edit]Blue laser pointers in specific wavelengths such as 473 nm usually have the same basic construction as DPSS green lasers. In 2006 many factories began production of blue laser modules for mass-storage devices, and these were used in laser pointers too. These were DPSS-type frequency-doubled devices. They most commonly emit a beam at 473 nm, which is produced by frequency doubling of 946 nm laser radiation from a diode-pumped Nd:YAG or Nd:YVO4 crystal (Nd-doped crystals usually produce a principal wavelength of 1064 nm, but with the proper reflective coating mirrors can be also made to lase at other "higher harmonic" non-principal neodymium wavelengths). For high output power, BBO crystals are used as frequency doublers; for lower powers, KTP is used. The Japanese company Nichia controlled 80% of the blue-laser-diode market in 2006.[11]

Some vendors are now selling collimated diode blue laser pointers with measured powers exceeding 1,500 mW. However, since the claimed power of "laser pointer" products also includes the IR power (in DPSS technology only) still present in the beam (for reasons discussed below), comparisons on the basis of strictly visual-blue components from DPSS-type lasers remain problematic, and the information is often not available. Because of the higher neodymium harmonic used, and the lower efficiency of frequency-doubling conversion, the fraction of IR power converted to 473 nm blue laser light in optimally configured DPSS modules is typically 10–13%, about half that typical for green lasers (20–30%).[citation needed]

Lasers emitting a violet light beam at 405 nm may be constructed with GaN (gallium nitride) semiconductors. This is close to ultraviolet, bordering on the very extreme of human vision, and can cause bright blue fluorescence, and thus a blue rather than violet spot, on many white surfaces, including white clothing, white paper, and projection screens, due to the widespread use of optical brighteners in the manufacture of products intended to appear brilliantly white — the brighteners are chemical compounds that absorb light in the violet (and ultraviolet) region of the electromagnetic spectrum and re-emit light in the blue region by fluorescence. On ordinary non-fluorescent materials, and also on fog or dust, the color appears as a shade of deep violet that cannot be reproduced on monitors and print. A GaN laser emits 405 nm directly without a frequency doubler, eliminating the possibility of accidental dangerous infrared emission. These laser diodes are mass-produced for the reading and writing of data in Blu-ray drives (although the light emitted by the diodes is not blue, but distinctly violet). In mid-to-late 2011, 405 nm blue-violet laser diode modules with an optical power of 250 mW, based on GaN violet laser diodes made for Blu-ray disc readers, had reached the market from Chinese sources for prices of about US$60 including delivery.[12]

Applications

[edit]Pointing

[edit]

Laser pointers are often used in educational and business presentations and visual demonstrations as an eye-catching pointing device. Laser pointers enhance verbal guidance given to students during surgery. The suggested mechanism of explanation is that the technology enables more precise guidance of location and identification of anatomic structures.[13]

Red laser pointers can be used in almost any indoor or low-light situation where pointing out details by hand may be inconvenient, such as in construction work or interior decorating. Green laser pointers can be used for similar purposes as well as outdoors in daylight or for longer distances.

Laser pointers are used in a wide range of applications. Green laser pointers can also be used for amateur astronomy.[14] Green lasers are visible at night due to Rayleigh scattering and airborne dust,[15] allowing someone to point out individual stars to others nearby. Also, these green laser pointers are commonly used by astronomers worldwide at star parties or for conducting lectures in astronomy. Astronomy laser pointers are also commonly mounted on telescopes in order to align the telescope to a specific star or location. Laser alignment is much easier than aligning through using the eyepiece.

Industrial and research use

[edit]

Laser pointers are used in industry. For instance, construction companies may use high quality laser pointers to enhance the accuracy of showing specific distances, while working on large-scale projects. They have proven to be useful in this type of business because of their accuracy, which made them significant time-savers. What is essentially a laser pointer may be built into an infrared thermometer to identify where it is pointing, or be part of a laser level or other apparatus.

They may also be helpful in scientific research in fields such as photonics, chemistry, physics, and medicine.

Laser pointers are used in robotics, for example, for laser guidance to direct the robot to a goal position by means of a laser beam, i.e. showing goal positions to the robot optically instead of communicating them numerically. This intuitive interface simplifies directing the robot while visual feedback improves the positioning accuracy and allows for implicit localization.[16][17]

Leisure and entertainment

[edit]Entertainment is one of the other applications that has been found for lasers. Clubs, parties and outdoor concerts may use high-power lasers, with safety precautions, as a spectacle. Laser shows are often extravagant, using lenses, mirrors and fog.

Laser pointers are a popular plaything for pets (e.g. cats, ferrets and dogs) whose natural predatory instincts are triggered by the moving laser and will chase it and/or unsuccessfully try to catch it as much as possible,[18] providing entertainment for the pet owner as well.

However, laser pointers have few applications beyond actual pointing in the wider entertainment industry, and many venues ban entry to those in possession of pointers as a potential hazard. Very occasionally laser gloves, which are sometimes mistaken for pointers, are seen being worn by professional dancers on stage at shows. Unlike pointers, these usually produce low-power highly divergent beams to ensure eye safety. Laser pointers have been used as props by magicians during magic shows.

As an example of the potential dangers of laser pointers brought in by audience members, at the Tomorrow Land Festival in Belgium in 2009, laser pointers brought in by members of the audience of 200 mW or greater were found to be the cause of eye damage suffered by several other members of the audience according to reports about the incident filed on the ILDA (International Laser Display Association's) Web site.[19] The report says that the incident was investigated by several independent authorities, including the Belgium police, and that those authorities concluded that pointers brought in by the audience were the cause of the injuries.

Laser pointers can be used in hiking or outdoor activities. It can be used as a rescue signal in emergencies which is visible to aircraft and other parties, during both day and night conditions, at extreme distances. For example, during the night in August 2010 two men and a boy were rescued from marshland after their red laser pen was spotted by rescue teams.[20]

Weapons systems

[edit]Accurately aligned laser pointers are used as laser gunsights to aim a firearm.

Hazards and risks

[edit]Incorrect power rating

[edit]National Institute of Standards and Technology tests[21] conducted on laser pointers labeled as Class IIIa or 3R in 2013 showed that about half of them emitted power at twice the Class limit, making their correct designation Class IIIb – more hazardous than Class IIIa. The highest measured power output was 66.5 milliwatts; more than 10 times the limit. Green laser light is generated from an infrared laser beam (Nd:YAG laser), which should be confined within the laser housing; however, more than 75% of the devices tested were found to emit infrared light in excess of the limit.

Malicious use

[edit]Laser pointers, with their very long range, are often maliciously shone at people to distract or annoy them, or for fun. This is considered particularly hazardous in the case of aircraft pilots, who may be dazzled or distracted at critical times.

According to an MSNBC report there were over 2,836 incidents logged in the US by the FAA in 2010.[22] Illumination by handheld green lasers is particularly serious, as the wavelength (532 nm) is near peak sensitivity of the dark-adapted eye and may appear to be 35 times brighter than a red laser of identical power output.[23]

Irresponsible use of laser pointers is often frowned upon by members of the laser projector community who fear that their misuse may result in legislation affecting lasers designed to be placed within projectors and used within the entertainment industry. Others involved in activities where dazzling or distraction are dangerous are also a concern.

Another distressing and potentially dangerous misuse of laser pointers is to use them when the dot may reasonably be mistaken for that of a laser gun sight. Armed police have drawn their weapons in such circumstances.[1]

Eye injury

[edit]The output of laser pointers available to the general public is limited (and varies by country) in order to prevent accidental damage to the retina of human eyes. The U.K. Health Protection Agency recommended that "laser pointers generally available to the public should be restricted to less than 1 milliwatt as no injuries [like the one reported below to have caused retinal damage] have been reported at this power".[24][25] In the U.S., regulatory authorities allow lasers up to 5 mW.

Studies have found that even low-power laser beams of not more than 5 mW can cause permanent retinal damage if gazed at for several seconds; however, the eye's blink reflex must be intentionally overcome to make this occur. Such laser pointers have reportedly caused afterimages, flash blindness and glare,[1] but not permanent damage, and are generally safe when used as intended.

A high-powered green laser pointer bought over the Internet was reported in 2010 to have caused a decrease of visual acuity from 6/6 to 6/12 (20/20 to 20/40); after two months acuity recovered to 6/6, but some retinal damage remained.[24][25] The US FDA issued a warning after two anecdotal reports it received of eye injury from laser pointers.[1]

Laser pointers available for purchase online can be capable of significantly higher power output than the pointers typically available in stores. Dubbed "Burning Lasers", these are designed to burn through light plastics and paper, and can have very similar external appearances to their low-power counterparts.[26][27] Because of their high power, many online retailers have warned high-power laser pointer users not to point them at humans or animals.

Studies in the early twenty-first century found that the risk to the human eye from accidental exposure to light from commercially available class IIIa laser pointers having powers up to 5 mW seemed rather small; however, prolonged viewing, such as deliberate staring into the beam for 10 or more seconds, can cause damage.[28][29][30][31]

The UK Health Protection Agency warns against the higher-power typically green laser pointers available over the Internet, with power output of up to a few hundred milliwatts, as "extremely dangerous and not suitable for sale to the public."[32]

Infrared hazards of DPSS laser pointers

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2018) |

Lasers classified as pointers are intended to have outputs less than 5 mW total power (Class 3R). At such power levels, an IR filter for a DPSS laser may not be required as the infrared (IR) output is relatively low and the brightness of the visible wavelength of the laser will cause the eye to react (blink reflex). However, higher-powered (> 5 mW) DPSS-type laser pointers have recently become available, usually through sources that do not follow laser safety regulations for laser packaging and labeling. These higher-powered lasers are often packaged in the same pointer-style housings as regular laser pointers, and usually lack the IR filters found in professional high-powered DPSS lasers, because of costs and additional efforts needed to accommodate them.[33]

Though the IR from a DPSS laser is less collimated, the typical neodymium-doped crystals in such lasers do produce a true IR laser beam. The eye will usually react to the higher-powered visible light; however, in higher power DPSS lasers the IR laser output can be significant. What poses a special hazard for this unfiltered IR output is its presence in conjunction with laser safety goggles designed to only block the visible wavelengths of the laser. Red goggles, for example, will block most green light from entering the eyes, but will pass IR light. The reduced light behind the goggles may also cause the pupils to dilate, increasing the hazard to the invisible IR light. Dual-frequency so-called YAG laser eyewear is significantly more expensive than single frequency laser eyewear, and is often not supplied with unfiltered DPSS pointer style lasers, which output 1064 nm IR laser light as well. These potentially hazardous lasers produce little or no visible beam when shone through the eyewear supplied with them, yet their IR-laser output can still be easily seen when viewed with an IR-sensitive video camera.

In addition to the safety hazards of unfiltered IR from DPSS lasers, the IR component may be inclusive of total output figures in some laser pointers.

Though green (532 nm) lasers are most common, IR filtering problems may also exist in other DPSS lasers, such as DPSS red (671 nm), yellow (589 nm) and blue (473 nm) lasers. These DPSS laser wavelengths are usually more exotic, more expensive, and generally manufactured with higher quality components, including filters, unless they are put into laser pointer style pocket-pen packages. Most red (635 nm, 660 nm), violet (405 nm) and darker blue (445 nm) lasers are generally built using dedicated laser diodes at the output frequency, not as DPSS lasers. These diode-based visible lasers do not produce IR light.

Regulations and misuse

[edit]Laser pointer users should not point laser beams at aircraft, moving vehicles, or towards strangers.[34] Since laser pointers became readily available, they have been misused, leading to the development of laws and regulations specifically addressing use of such lasers. Their very long range makes it difficult to find the source of a laser spot. In some circumstances they make people fear they are being targeted by weapons, as they are indistinguishable from dot type laser reticles. The very bright, small spot makes it possible to dazzle and distract drivers and aircraft pilots, and they can be dangerous to sight if aimed at the eyes.

In 1998, an audience member shone a laser at Kiss drummer Peter Criss's eyes while the band was performing "Beth". After performing the song, Criss nearly stormed off the stage, and lead singer Paul Stanley ripped into whoever had been manipulating the laser light:

In every crowd, there's one or two people who don't belong [...] Now I know you want to [take] it to school tomorrow when you go to sixth grade, but [you should have left] it at home [before coming] to the show.

According to FIFA stadium safety and security regulations, laser pointers are prohibited items at stadiums during FIFA football tournaments and matches.[37] They are also prohibited in matches and competitions organised by UEFA.[38] In 2008 laser pointers were aimed at players' eyes in a number of sport matches worldwide. Olympique Lyonnais was fined by UEFA because of a laser pointer beam aimed by a Lyon fan at Cristiano Ronaldo.[39] In a World Cup final qualifier match held in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia between the home team and the South Korean team, South Korean goalkeeper Lee Woon-Jae was hit in the eye with a green laser beam.[40] At the 2014 World Cup during the final group stage match between Algeria and Russia a green laser beam was directed on the face of Russian goalkeeper Igor Akinfeev. After the match the Algerian Football Federation was fined CHF50,000 (approx. £33,000/€41,100/US$56,200) by FIFA for the use of lasers and other violations of the rules by Algerian fans at the stadium.[41] During a football match in Athens between Greece and Ireland on 16 June 2023, Greek supporters were asked repeatedly over the public address system to stop shining laser beams at the Irish footballers.[42]

In 2009 police in the United Kingdom began tracking the sources of lasers being shone at helicopters at night, logging the source using GPS, using thermal imaging cameras to see the suspect, and even the warm pointer if discarded, and calling in police dog teams. As of 2010 the penalty could be five years' imprisonment.[43]

Despite legislation limiting the output of laser pointers in some countries, higher-power devices are currently produced in other regions and are frequently imported by customers who purchase them directly via Internet mail order. The legality of such transactions is not always clear; typically, the lasers are sold as research or OEM devices (which are not subject to the same power restrictions), with a disclaimer that they are not to be used as pointers. DIY videos are also often posted on Internet video sharing sites like YouTube which explain how to make a high-power laser pointer using the diode from an optical disc burner. As the popularity of these devices increased, manufacturers began manufacturing similar high-powered pointers. Warnings have been published on the dangers of such high-powered lasers.[44] Despite the disclaimers, such lasers are frequently sold in packaging resembling that for laser pointers. Lasers of this type may not include safety features sometimes found on laser modules sold for research purposes.

There have been many incidents regarding, in particular, aircraft, and the authorities in many countries take them extremely seriously. Many people have been convicted and sentenced, sometimes to several years' imprisonment.[45]

Australia

[edit]In April 2008, citing a series of coordinated attacks on passenger jets in Sydney, the Australian government announced that it would restrict the sale and importation of certain laser items. The government had yet to determine which classes of laser pointers to ban.[46] After some debate, the government voted to ban importation of lasers that emit a beam stronger than 1 mW, effective from 1 July 2008. Those whose professions require the use of a laser can apply for an exemption.[47] In Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory a laser pointer with an accessible emission limit greater than 1 mW is classified as a prohibited weapon and any sale of such items must be recorded.[48][49] In Western Australia, regulatory changes have classified laser pointers as controlled weapons and demonstration of a lawful reason for possession is required.[50] The WA state government has also banned as of 2000 the manufacture, sale and possession of laser pointers higher than class 2.[51] In New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory the product safety standard for laser pointers prescribes that they must be a Class 1 or a Class 2 laser product.[52][53] In February 2009 South African cricketer Wayne Parnell had a laser pointer directed at his eyes when attempting to take a catch, which he dropped. He denied that it was a reason for dropping the ball, but despite this the MCG decided to keep an eye out for the laser pointers. The laser pointer ban only applies to hand-held battery-powered laser devices and not laser modules.[54]

In November 2015 a 14-year-old Tasmanian boy damaged both his eyes after shining a laser pen "... in his eyes for a very brief period of time". He burned his retinas near the macula, the area where most of a person's central vision is located. As a result, the boy has almost immediately lost 75% of his vision, with little hope of recovery.[55]

Canada

[edit]New regulations controlling the importation and sale of laser pointers (portable, battery-powered) have been established in Canada in 2011 and are governed by Health Canada using the Consumer Protection Act for the prohibition of the sale of Class 3B (IEC) or higher power lasers to "consumers" as defined in the Consumer Protection Act . Canadian federal regulation follows FDA (US Food & Drug Administration) CDRH, and IEC (International Electrotechnical Commission) hazard classification methods where manufacturers comply with the Radiation Emitting Devices Act. As of July 2011 three people[56] had been charged under the federal Aeronautics Act, which carries a maximum penalty of $100,000 and five years in prison, for attempting to dazzle a pilot with a laser. Other charges that could be laid include mischief and assault.[57]

Colombia

[edit]The "RESOLUCIÓN 57151 DE 2016" prohibits the marketing and making available to consumers of laser pointers with output power equal to or greater than one milliwatt (>=1 mW).[58] Colombia is the first country in South America to regulate the marketing of these products.

Hong Kong

[edit]Laser pointers are not illegal in Hong Kong but air navigation rules state that it is an offense to exhibit "any light" bright enough to endanger aircraft taking off or landing.

During the 2019–20 Hong Kong protests, laser pointers were used by protesters to confuse police officers and scramble facial recognition cameras. On August 6, 5 off-duty police officers arrested Baptist University student union president Keith Fong Chung-yin after he purchased 10 laser pointers in Sham Shui Po for possession of "offensive weapons". Fong said he would use the pointers for stargazing, but police described them as “laser guns” whose beams could cause eye injuries. In defence of the arrest, police said that under Hong Kong law the pointers can be deemed “weapons” if they are used in or intended for use in an attack. The incident led to a public outcry. Human rights activist Icarus Wong Ho-yin said that going by the police explanation, “a kitchen worker who buys a few knives can be arrested for being in possession of offensive weapons”. Democratic Party lawmaker and lawyer James To Kun-sun criticized the police for abuse of power. Hundreds of protesters gathered outside the dome of Hong Kong's Space Museum to put on a “laser show” to denounce police's claims that these laser pointers were offensive weapons. Fong was released unconditionally two days later.[59]

Netherlands

[edit]Before 1998 Class 3A lasers were allowed. In 1998 it became illegal to trade Class 2 laser pointers that are "gadgets" (e.g. ball pens, key chains, business gifts, devices that will end up in children's possession, parts of toys, etc.). It is still allowed to trade Class 2 (< 1 mW) laser pointers proper, but they have to meet requirements regarding warnings and instructions for safe use in the manual. Trading of Class 3 and higher laser pointers is not allowed.[60]

Sweden

[edit]The use of pointers with output power > 1 mW is regulated in public areas and school yards.[61] From 1 January 2014 it is necessary to have a special permit in order to own a laser pointer with a classification of 3R, 3B or 4, i.e. over 1 mW.[62]

Switzerland

[edit]In Switzerland, the possession of laser pointers has been prohibited since 1 June 2019, except for class 1 laser pointers, which may be used only indoors.[63]

United Kingdom

[edit]UK and most of Europe are now harmonized on Class 2 (<1 mW) for General presentation use laser pointers or laser pens. Anything above 1 mW is illegal for sale in the UK (import is unrestricted). Health and Safety regulation insists on use of Class 2 anywhere the public can come in contact with indoor laser light, and the DTI have urged Trading Standards authorities to use their existing powers under the General Product Safety Regulations 2005 to remove lasers above class 2 from the general market.[64]

Since 2010, it is an offence in the UK to shine a light at an aircraft in flight so as to dazzle the pilot, whether intentionally or not, with a maximum penalty of a level 4 fine (currently £2500). It is also an offence to negligently or recklessly endanger an aircraft, with a maximum penalty of five years imprisonment and/or an unlimited fine.[65]

To assist with enforcement, police helicopters use GPS and thermal imaging camera, together with dog teams on the ground, to help locate the offender; the discarded warm laser pointer is often visible on the thermal camera, and its wavelength can be matched to that recorded by an event recorder in the helicopter.[66]

United States

[edit]Laser pointers are Class II or Class IIIa devices, with output beam power less than 5 milliwatts (<5 mW). According to U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations, more powerful lasers may not be sold or promoted as laser pointers.[67] Also, any laser with class higher than IIIa (more than 5 milliwatts) requires a key-switch interlock and other safety features.[68] Shining a laser pointer of any class at an aircraft is illegal and punishable by a fine of up to $11,000.[69]

All laser products offered in commerce in the US must be registered with the FDA, regardless of output power.[68][70]

Arizona

[edit]In Arizona it is a Class 1 misdemeanor if a person "aims a laser pointer at a police officer if the person intentionally or knowingly directs the beam of light from an operating laser pointer at another person and the person knows or reasonably should know that the other person is a police officer." (Arizona Revised Statutes §13-1213) [71]

Michigan

[edit]Public act 257 of 2003 makes it a felony for a person to "manufacture, deliver, possess, transport, place, use, or release" a "harmful electronic or electromagnetic device" for "an unlawful purpose"; also made into a felony is the act of causing "an individual to falsely believe that the individual has been exposed to a... harmful electronic or electromagnetic device."[72]

Public act 328 of 1931 makes it a felony for a person to "sell, offer for sale, or possess" a "portable device or weapon from which an electric current, impulse, wave, or beam may be directed" and is designed "to incapacitate temporarily, injure, or kill".[73]

Maine

[edit]Public law 264, H.P. 868 - L.D. 1271 criminalizes the knowing, intentional, and/or reckless use of an electronic weapon on another person, defining an electronic weapon as a portable device or weapon emitting an electric current, impulse, beam, or wave with disabling effects on a human being.[74]

Massachusetts

[edit]Chapter 170 of the Acts of 2004, Section 140 of the General Laws, section 131J states: "No person shall possess a portable device or weapon from which an electric current, impulse, wave or beam may be directed, which current, impulse, wave or beam is designed to incapacitate temporarily, injure or kill, except ... Whoever violates this section shall be punished by a fine of not less than $500 nor more than $1,000 or by imprisonment in the house of correction for not less than 6 months nor more than 2 1/2 years, or by both such fine and imprisonment." [75]

Utah

[edit]In Utah it is a class C misdemeanor to point a laser pointer at a law enforcement officer and is an infraction to point a laser pointer at a moving vehicle.[76]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Princeton University: Safety Recommendations for Laser Pointers. Web.princeton.edu. Retrieved on 15 October 2011.

- ^ Laser Beam and Dot Relative Brightness Comparison by Wavelength. 405nm.com. Retrieved on 8 April 2023.

- ^ ANSI classification scheme (ANSI Z136.1–1993, American National Standard for Safe Use of Lasers).

- ^ FDA Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, Subchapter J: Radiological Health, PART 1040 – PERFORMANCE STANDARDS FOR LIGHT-EMITTING PRODUCTS. Accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved on 15 October 2011.

- ^ "Product Guide". Popular Science. November 1981.

- ^ Marshall, Larry R. (27 January 1997). "Solving the Green Problem". Advanced Solid State Lasers (1997), paper VL4. Optica Publishing Group: VL4. doi:10.1364/ASSL.1997.VL4.

- ^ Sam's Laser FAQ: Dissection of Green Laser Pointer Archived 22 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. repairfaq.org

- ^ Green diode lasers a big breakthrough for laser-display tech (i-micronews.com via arstechnica.com).

- ^ LASER Diode-NICHIA CORPORATION Archived 18 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine. nichia.co.jp

- ^ Green Laser, Visible Laser – OSRAM Opto Semiconductors. osram-os.com

- ^ Qiu, Jane (14 September 2006). "Is the end in sight for Sony's laser blues?". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ In September 2011, GaN diode laser modules capable of operating at 250mW (or 300mW pulse) with a heatsink were offered on eBay in the Industrial Lasers category at around US$60.

- ^ Badman, Märit; Höglund, Katja; Höglund, Odd V. (2016). "Student Perceptions of the Use of a Laser Pointer for Intra-Operative Guidance in Feline Castration". Journal of Veterinary Medical Education. 43 (2): 1–3. doi:10.3138/jvme.0515-084r2. PMID 27128854.

- ^ Bará, S; Robles, M; Tejelo, I; Marzoa, RI; González, H (2010). "Green laser pointers for visual astronomy: how much power is enough?". Optometry and Vision Science. 87 (2): 140–4. doi:10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181cc8d8f. PMID 20035242. S2CID 5614966.

- ^ Metzger, Robert M. (2012). The Physical Chemist's Toolbox. John Wiley & Sons. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-470-88925-1. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ Paromtchik, Igor (2006). "Optical Guidance Method for Robots Capable of Vision and Communication" (PDF). Robotics and Autonomous Systems. 54 (6). Elsevier: 461–471. doi:10.1016/j.robot.2006.02.005.

- ^ "Mobile Robot Guidance by Laser Pointer" (Video). YouTube. 15 October 2013. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Hyman, Ira (11 January 2011). "It's Alive! Why Cats Love Laser Pointers". Psychology Today. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ laserist.org Archived 27 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine. laserist.org. Retrieved on 15 October 2011.

- ^ UK Marine and Coastguard Agency Archived 29 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Nds.coi.gov.uk. Retrieved on 15 October 2011.

- ^ "NIST Tests Underscore Potential Hazards of Green Laser Pointers". NIST. Nist.gov. 20 March 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ^ "FAA: Laser incidents soar, threaten planes - Travel - News". MSNBC. 20 January 2011. Archived from the original on 21 January 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Nakagawara, Van B., DO. "Laser Hazards in Navigable Airspace" (PDF). FAA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Laser pointers 'pose danger to eyes'". BBC News. 9 June 2010.

- ^ a b Maculopathy from handheld green diode laser pointer, Kimia Ziahosseini, et a., BMJ 2010;340:c2982

- ^ Wyrsch, Stefan; Baenninger, Philipp B.; Schmid, Martin K. (2010). "Retinal Injuries from a Handheld Laser Pointer". N Engl J Med. 363 (11): 1089–1091. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1005818. PMID 20825327.

- ^ Gordon, Serena (8 September 2010) Kids Playing With Laser Pointers May Be Aiming for Eye Trouble; Teen boy damages retina with Internet-purchased 'toy,' doctors say Archived 16 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Bloomberg BusinessWeek

- ^ Mainster, M. A.; Stuck, B. E.; Brown Jr, J (2004). "Assessment of Alleged Retinal Laser Injuries". Arch Ophthalmol. 122 (8): 1210–1217. doi:10.1001/archopht.122.8.1210. PMID 15302664.

- ^ Robertson, D. M.; McLaren, J. W.; Salomao, D. R.; Link, T. P. (2005). "Retinopathy From a Green Laser Pointer: a Clinicopathologic Study". Arch. Ophthalmol. 123 (5): 629–633. doi:10.1001/archopht.123.5.629. PMID 15883281.

- ^ Sliney DH, Dennis JE (1994). "Safety concerns about laser pointers". J. Laser Appl. 6 (3): 159–164. Bibcode:1994JLasA...6..159S. doi:10.2351/1.4745352.

- ^ Mainster, M. A.; Stuck, B. E.; Brown Jr, J (2004). "Assessment of Alleged Retinal Laser Injuries". Arch Ophthalmol. 122 (8): 1210–1217. doi:10.1001/archopht.122.8.1210. PMID 15302664.

- ^ UK Health Protection Agency Information Sheet on Laser Pointers Archived 13 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Hpa.org.uk (21 May 2010). Retrieved on 2011-10-15.

- ^ Galang, Jemellie; Restelli, Alessandro; Hagley, Edward W.; Clark, Charles W. (2 August 2010). "A Green Laser Pointer Hazard". NIST. arXiv:1008.1452.

- ^ Laser Pointer Safety - NEVER aim laser pointers at aircraft

- ^ "Laser Pointer Irks Kiss". Beaver County Times. 24 November 1998. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ Chapman, Francesca (24 November 1998). "Kiss Drummer Sees Red, Rips Dimwit With Laser Pointer". Philly.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ FIFA Stadium Safety and Security Regulations — see page 96, "g"

- ^ UEFA Disciplinatory Regulations — see page 9, "2.d"

- ^ – Laser Zap Leads to Soccer Fine. Blog.wired.com (22 March 2008). Retrieved on 2011-10-15.

- ^ kfa.or.kr/sportalkorea – 사우디 관중, 이운재에 레이저 포인터 공격 (includes a photograph showing a laser beam shining upon the goalkeeper's face)

- ^ Evans, Simon (1 July 2014). "Algeria zapped with FIFA fine over lasers". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ Ireland's Greek odyssey ends in disappointing defeat RTÉ Sport, 23-06-16.

- ^ Symonds, Tom (8 April 2009). "Police fight back on laser threat". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ US FDA: Consumer Safety Alert: Internet Sales of Laser Products. Fda.gov (6 September 2011). Retrieved on 2011-10-15.

- ^ News of aviation-related incidents, arrests, etc. Laser Pointer Safety. Retrieved on 15 October 2011.

- ^ "Laser pointers restricted after attacks". Sydney Morning Herald. 6 April 2008. Archived from the original on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2008.

- ^ Minister media release. Importation of laser pointers banned. Australian Customs Service. Friday, 30 May 2008

- ^ Control of Weapons Regulations 2000 Archived 10 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine S.R. No. 130/2000 Schedule 2 Number 33

- ^ Fact Sheet: Prohibited Weapons, Laser Pointers, May_2010, NSW Police Force

- ^ Kobelke, John (13 April 2008) Laser pointers are now controlled weapons Archived 27 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Government of Western Australia.

- ^ Day, John (3 January 2000) The State Government has banned the manufacture, sale and possession of laser pointers Archived 27 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Government of Western Australia.

- ^ Extract from New South Wales Fair Trading Regulation 2007. Legislation.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved on 15 October 2011

- ^ Fair Trading (Consumer Product Standards) Regulation 2002. Republication date: 3 April 2008

- ^ "Australian Customs on Firearms and Weapons". Customs.gov.au. 21 April 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Ross, Selina (5 November 2015). "Laser pointers not toys, optometrists warn, after Tasmanian teenager damages eyes". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ "Laser Shone at Police Chopper, Oshawa Man Charged". Oshawa This Week. 29 July 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ "TELUS". Mytelus.com. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ^ "RESOLUCIÓN 57151 DE 2016" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ "Police defend arrest of Baptist University student leader for carrying laser pointers". South China Morning Post. 7 August 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Brief minister over laserpointers – Vaststelling van de begroting van de uitgaven en de ontvangsten van het Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport (XVI) voor het jaar 1999. Letter from the minister of health care to Dutch Parliament, no. 71, 11 June 1999.

- ^ Laserpekare (in Swedish)

- ^ Skärpta regler för starka laserpekare från 1 januari 2014(in Swedish)

- ^ "Laser pointers". Federal Office of Public Health. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ The UK Health Protection Agency's Laser Pointer Infosheet Archived 13 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Air Navigation Order 2009. For the strict liability offence, see paragraphs 222 and 241(6) and part B of schedule 13 of the Order. For reckless endangerment, see paragraphs 137 and 241(8) and part D of schedule 13 of the Order.

- ^ Symonds, Tom (8 April 2009). "Technology | Police fight back on laser threat". BBC News. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ "Important Information for Laser Pointer Manufacturers". www.fda.gov. Food and Drug Administration. 4 December 2017. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ a b U.S. Code of Federal Regulations,"21 CFR 1040.10 Performance standards for Light-Emitting products - Laser products". www.fda.gov. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 2 November 2002. Retrieved 26 November 2021. Note that these regulations pre-date the availability of Laser Pointers and so do not reference them by name.

- ^ "FAA News Briefing". faa.gov. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ "Illuminating Facts About Laser Pointers". www.fda.gov. Food and Drug Administration. 13 June 2019. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ "Format Document". Azleg.gov. Archived from the original on 20 November 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ^ "2003-PA-0257". Legislature.mi.gov. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ "Michigan Legislature - Section 750.224a". Legislature.mi.gov. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ "PUBLIC Law Chapter 264". Mainelegislature.org. 15 January 2003. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- ^ "Session Laws: CHAPTER 170 of the Acts of 2004". Malegislature.gov. 15 July 2004. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- ^ Utah State Legislature 76-10-2501 Unlawful use of a laser pointer Archived 10 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine Most states now have similar laws to Utah's making some uses of laser pointers (such as pointing one at a police officer or an aircraft (federal law) a crime)

Further reading

[edit]- J.A. Hadler and M.L. Dowell, "Accurate, inexpensive testing of handheld lasers for safe use and operation." Meas.Sci.Technol. 24 (2013) 045202.

External links

[edit]Laser pointer

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins in laser technology

The principle underlying laser pointers derives from the stimulated emission of radiation, first theoretically described by Albert Einstein in 1917 as a mechanism for amplifying light through coherent photon release.[7] This concept evolved into the maser (microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation) in 1954, demonstrated by Charles Townes and colleagues using ammonia gas, which laid the groundwork for optical lasers by achieving population inversion in atomic systems.[8] The first operational laser was constructed by Theodore Maiman at Hughes Research Laboratories on May 16, 1960, employing a synthetic ruby crystal pumped by a flashlamp to produce pulsed infrared output at 694.3 nm, marking the practical realization of coherent light amplification.[9] However, this ruby laser's pulsed nature and initial infrared emission limited its utility for visible pointing devices. Shortly thereafter, in December 1960, Ali Javan, William Bennett, and Donald Herriott at Bell Laboratories demonstrated the first continuous-wave (CW) laser using a helium-neon (HeNe) gas mixture, initially emitting at 1.15 μm in the infrared; subsequent refinements yielded visible red output at 632.8 nm by exciting neon atoms via helium collisions in a low-pressure discharge tube.[10] The HeNe design's stable, low-divergence beam—enabled by its four-level energy scheme and gaseous medium—proved ideal for early pointing applications, as it maintained visibility over distances without the intermittency of solid-state predecessors. Commercialization of HeNe lasers facilitated the emergence of portable pointers. In 1964, Spectra-Physics introduced the Model 130, a compact HeNe unit with an integrated DC power supply and ergonomic handle, explicitly marketed and used as the inaugural "laser pointer" for lectures and alignments, outputting approximately 1 mW at 632.8 nm. These devices leveraged the core laser technology's reliance on optical feedback via aligned mirrors and gain media to produce collimated beams, distinguishing them from incoherent light sources like flashlights and enabling precise targeting in astronomy, presentations, and surveying. Early HeNe pointers required high-voltage excitation (around 1-2 kV) and were bulky compared to modern diode-based models, reflecting the nascent stage of laser miniaturization.Development of portable devices

The helium-neon (HeNe) laser, invented in December 1960 by Ali Javan, William Bennett Jr., and Donald Herriott at Bell Laboratories, provided the first continuous-wave visible output at 632.8 nm, enabling practical pointing applications due to its stable red beam.[10] Early HeNe systems were laboratory-scale, requiring AC high-voltage power supplies and fixed mounts, limiting mobility.[11] Development of portable variants accelerated in the mid-1960s with efforts to integrate compact DC power supplies and ergonomic designs. In 1964, Spectra-Physics released the Model 130B, a 1 mW HeNe laser with a built-in DC supply and pistol-grip handle, recognized as the inaugural handheld laser pointer for demonstrations and alignments.[12] This device, weighing several pounds and powered by external batteries, represented a shift from stationary setups by allowing untethered operation over short distances. Subsequent refinements in the late 1960s and 1970s emphasized tube miniaturization—reducing bore diameters to 0.5–1 mm for lower power thresholds—and efficient ballast resistors for stable discharge at milliwatt levels.[13] Companies like Melles Griot and Uniphase produced battery-compatible HeNe pointers by the early 1970s, typically 12–18 inches long and outputting 0.5–2 mW, suitable for lectures and surveying despite requiring helium-neon gas refills every few thousand hours.[14] These units achieved portability through lightweight glass capillaries and transistorized supplies operating at 1–2 kV, though high voltage necessitated insulated housings to mitigate shock risks.[15] By the late 1970s, portable HeNe pointers cost $200–500 and weighed 1–3 pounds, facilitating use in astronomy for star pointing and in theaters for effects, but their gas consumption and fragility constrained mass adoption.[16] Output stability relied on precise helium-to-neon ratios (typically 10:1) and mirror alignments, with beam divergence around 1–2 mrad enabling visibility up to 100 meters in darkness.[17] These gas-based portables laid groundwork for pointing devices before semiconductor alternatives, prioritizing coherence over compactness.Shift to semiconductor-based pointers

The initial laser pointers, introduced in the early 1980s, predominantly utilized helium-neon (HeNe) gas lasers operating at a wavelength of 632.8 nm, which necessitated cumbersome glass tubes, high-voltage excitation, and substantial power supplies, limiting portability and increasing costs to several hundred dollars per unit.[11] These devices produced a coherent red beam suitable for pointing but were impractical for widespread consumer adoption due to their size—often exceeding 30 cm in length—and fragility.[18] Advancements in semiconductor laser technology, beginning with the invention of the diode laser in 1962 using gallium arsenide (GaAs) for infrared emission, paved the way for visible-spectrum alternatives.[19] Key breakthroughs included the demonstration of continuous-wave operation at room temperature in 1970 by researchers at RCA Laboratories and the first commercial room-temperature continuous-wave diode laser in 1975 by Laser Diode Labs.[11] By the mid-1980s, aluminum gallium arsenide (AlGaAs) and later aluminum gallium indium phosphide (AlGaInP) diode lasers achieved visible red output around 670 nm, enabling compact designs powered by simple batteries without gas discharge requirements.[20] This shift was driven by diodes' superior efficiency—converting electrical current directly to coherent light via stimulated emission in p-n junctions—resulting in devices under 15 cm long, with power outputs of 1-5 mW, and costs dropping below $50 by the early 1990s.[21] The transition accelerated consumer accessibility, as diode-based pointers offered longer operational lifetimes (thousands of hours versus hundreds for HeNe), reduced maintenance, and mass-producibility through semiconductor fabrication techniques akin to those for LEDs.[18] By the late 1990s, HeNe models were largely supplanted in commercial markets, with diode lasers dominating due to their causal advantages in scalability and reliability, though early diodes exhibited higher beam divergence necessitating improved collimating optics.[22] This evolution marked a paradigm change from vacuum-tube gas dynamics to solid-state electron-hole recombination, fundamentally enabling the portable, ubiquitous pointing tools seen today.[21]Technical principles

Laser emission basics

Laser emission in a laser pointer, as in all lasers, relies on the principle of stimulated emission of radiation, where photons trigger excited atoms or molecules in a gain medium to release additional photons of identical wavelength, phase, direction, and polarization.[23] This contrasts with spontaneous emission, in which excited particles decay randomly, producing incoherent light.[24] Stimulated emission was theoretically predicted by Albert Einstein in 1917 and forms the basis for light amplification.[23] To achieve net amplification, a population inversion must be established in the gain medium, where a higher proportion of atoms or molecules occupy a higher-energy excited state compared to the lower-energy ground state, inverting the natural thermal equilibrium distribution.[25] This non-equilibrium condition is created by an external energy pump, such as electrical discharge, optical excitation, or chemical reactions, which raises electrons to metastable upper energy levels with longer lifetimes than the lower levels.[26] Without population inversion, absorption dominates, preventing gain; with it, incoming photons stimulate cascading emissions, exponentially amplifying the light intensity as it passes through the medium.[23] The amplification occurs within an optical resonator or cavity, typically formed by two mirrors—one fully reflective and one partially transmissive—positioned at the ends of the gain medium to confine and reflect the light multiple times, building coherence and directionality.[26] Photons aligned with the cavity's resonant modes undergo repeated stimulated emissions, resulting in a narrow, collimated beam of monochromatic, coherent light that exits through the output coupler.[25] In laser pointers, this process yields a highly directional output, distinguishing it from divergent sources like LEDs.[27] The resulting laser light exhibits low divergence (typically <1 milliradian for pointers) and high spatial and temporal coherence, enabling the characteristic tight spot over distance.[23]Diode versus DPSS mechanisms

Direct diode laser pointers employ a semiconductor laser diode as the primary light source, where electrical current directly stimulates electron-hole recombination to produce coherent visible light emission, typically in the red spectrum at wavelengths around 650–660 nm using materials like AlGaInP.[28] This mechanism is inherently simple, consisting of the diode chip, a collimating lens, and minimal optics, enabling compact designs with high electrical-to-optical efficiency often exceeding 20% for low-power outputs under 5 mW.[29] Direct diodes offer instant activation without warm-up and rapid modulation capabilities, suitable for battery-powered handheld devices, though their output beams exhibit astigmatism and higher divergence (typically 5–10 mrad full angle) due to the diode's multimode nature and short cavity length.[30] In contrast, diode-pumped solid-state (DPSS) mechanisms in laser pointers use an infrared laser diode (e.g., at 808 nm) to optically pump a rare-earth-doped crystal such as Nd:YVO₄ or Nd:YAG, exciting ions to achieve population inversion and stimulated emission at 1064 nm infrared.[29] This fundamental wavelength is then frequency-doubled via nonlinear second-harmonic generation in a crystal like KTP or LBO to produce visible green light at 532 nm, with additional filters to suppress residual infrared.[30] The assembly includes the pump diode, gain medium, doubling crystal, and precision alignment optics, resulting in greater complexity and potential for thermal lensing or mode instability during operation.[29] DPSS systems predominate in higher-quality green pointers due to their ability to generate exact 532 nm output, historically unavailable from direct diodes until advancements in InGaN semiconductors enabled 520 nm direct green diodes around 2010.[31] Comparatively, direct diode pointers excel in cost-effectiveness (often under $10 for basic red models) and simplicity, with no risk of infrared leakage, but suffer from inferior beam quality (M² factor >1.5, leading to elliptical spots and higher divergence) that limits visible range and spot sharpness without corrective optics.[30][28] DPSS pointers provide superior beam parameters, including near-diffraction-limited TEM₀₀ mode, divergence as low as 0.5–1 mrad, and circular spots ideal for precise pointing over distances, though at higher manufacturing costs (2–10 times that of equivalent diode units) and lower overall efficiency (5–15% wall-plug) due to multi-stage losses and potential IR contamination requiring suppression.[29][30] DPSS also demands stabilization against temperature-induced mode hopping, often necessitating longer warm-up times (seconds to minutes), whereas diodes maintain stability across operating ranges.[30] In practice, red pointers remain almost exclusively direct diode for their reliability in consumer applications, while green variants leverage DPSS for beam coherence until direct 532 nm diodes mature, balancing trade-offs in power scalability where DPSS supports higher outputs with maintained quality up to hundreds of mW.[32][29]| Aspect | Direct Diode | DPSS |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Wavelengths | Red (650–660 nm); green/blue (520 nm, 450 nm) with modern diodes | Green (532 nm) via frequency doubling; extensible to UV/IR |

| Beam Divergence | Higher (5–10 mrad) | Lower (0.5–1 mrad) |

| Efficiency | Higher (20%+) for visible direct | Lower (5–15%) due to pumping/doubling losses |

| Cost/Complexity | Low/simple | High/complex |

| Stability | Instant on, minimal mode hopping | Warm-up required, potential IR leak |

Wavelengths and visible spectrum output

Laser pointers emit monochromatic coherent light at discrete wavelengths within the visible spectrum, defined as approximately 380 to 740 nm where human vision is sensitive, though peak sensitivity occurs around 555 nm in the green-yellow region.[33] Output is confined to narrow spectral lines, typically less than 1-5 nm bandwidth, producing pure colors unlike broadband sources such as LEDs.[34] This specificity arises from the lasing medium—direct diode emission or frequency-doubled processes—ensuring high visibility for pointing applications despite low power levels, often 1-5 mW.[35] Common commercial laser pointers operate at red wavelengths of 635-670 nm using semiconductor diodes, with 650 nm being prevalent in early models due to diode availability, though 635 nm offers superior perceived brightness from the same power owing to closer alignment with eye sensitivity curves.[36][37] Green output, the most visible color for equivalent power, centers at 532 nm via diode-pumped solid-state (DPSS) frequency doubling of 1064 nm infrared Nd:YAG emission or direct 515-520 nm diodes in newer devices; human photopic response renders 532 nm up to four times brighter than 650 nm red.[38] Blue and violet pointers use 445-450 nm or 405 nm diodes, respectively, where 405 nm borders ultraviolet and induces fluorescence in some materials, reducing direct visibility but enabling effects like purple glows; eye sensitivity drops sharply below 450 nm, making these appear dimmer than green despite comparable power.[35] Less common wavelengths include yellow at 589 nm (DPSS from 1176 nm doubling) or orange at 593 nm, primarily for specialized uses like astronomy pointers due to atmospheric scattering advantages over red.[39] Visibility in the spectrum follows the CIE 1931 photopic luminosity function, peaking in green and declining toward red and violet edges, such that for safety-class 1 mW output, green beams remain discernible over longer distances in daylight than red or blue equivalents.[38] Regulatory limits, such as IEC 60825-1, classify visible lasers (400-700 nm) up to 5 mW as Class 3R, emphasizing wavelength-dependent retinal hazard where shorter blues pose photochemical risks despite lower perceived brightness.[40]| Color | Typical Wavelength (nm) | Emission Mechanism | Visibility Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red | 635, 650, 670 | Diode | Lower eye sensitivity; common in low-cost pointers.[36][41] |

| Green | 515-520, 532 | Diode or DPSS | Highest brightness per watt; preferred for presentations. |

| Blue | 445-450 | Diode | Moderate visibility; scatters more in air.[35] |

| Violet | 405 | Diode | Edge of visibility; causes fluorescence. |

| Yellow | 589 | DPSS | Rare; low scattering for stargazing.[39] |

Design and specifications

Power output and safety classifications

Laser pointers emit coherent light in continuous-wave (CW) mode, with power output quantified in milliwatts (mW) as the average radiant power from the aperture. Regulatory limits cap consumer-grade pointers at 5 mW maximum for visible wavelengths (400-710 nm) under U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rules, corresponding to Class IIIa (equivalent to IEC Class 3R), to restrict potential for retinal photothermal or photochemical injury from direct beam exposure.[42] [42] Devices exceeding this threshold, such as those reaching 10-500 mW or more in unregulated markets, shift to higher-risk categories and are prohibited for general pointing use, as even momentary direct ocular exposure at these levels can induce permanent vision loss without reliance on aversion reflexes.[42] [43] International safety standards, primarily IEC 60825-1 (edition 3.0, 2014), classify lasers by accessible emission level (AEL), wavelength, and exposure duration, prioritizing eye hazard from visible (400-700 nm) beams where the cornea and lens focus radiation onto the retina. Class 1 lasers pose no hazard under normal use, with AEL below natural background levels. Class 2 visible lasers, typically <1 mW, depend on the involuntary blink reflex (aversion time ~0.25 seconds) for protection against intrabeam viewing, rendering them suitable for brief accidental exposures in pointers.[44] [45] [45] Class 3R encompasses pointers up to 5 mW for CW visible output, where direct staring can exceed maximum permissible exposure (MPE) thresholds—e.g., 1 mW/cm² for 400-700 nm at 10 seconds—potentially causing moderate retinal burns, though diffuse reflections remain low-risk.[43] [45] Class 3B (>5 mW to 500 mW) and Class 4 (>500 mW) lasers, unsuitable for consumer pointers, demand engineered safeguards like interlocks and eyewear, as they enable skin burns, fire ignition, and immediate eye ablation even from specular reflections.[43] [45] FDA enforcement treats pointers as "laser products" under 21 CFR 1040.10-11, requiring labeling of class and emissions but no mandatory certification, leading to widespread non-compliance in imported high-power units mislabeled as compliant.[42] [42]| Class | Max CW Power (Visible, mW) | Eye Safety Mechanism | Pointer Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | <0.39 (AEL limit) | Inherently safe | Enclosed systems only |

| 2 | <1 | Blink reflex | Low-power pointers |

| 3R | 1-5 | Limited aversion | Standard consumer pointers |

| 3B | 5-500 | Protective eyewear required | Not for pointers |

| 4 | >500 | Full barriers/eyewear | Industrial only |

Beam characteristics and optics

Laser pointer beams exhibit high spatial and temporal coherence, monochromatic output, and strong collimation, enabling them to propagate with minimal spreading compared to incoherent sources like LEDs. The beam divergence, defined as the full angle over which the beam diameter increases due to diffraction, is typically low at 1 to 2 milliradians (mrad) for commercial devices, allowing spot sizes to remain under 1 mm at distances up to several hundred meters under ideal conditions.[46][47] This low divergence arises from the small emitting aperture of the laser source and precise optical collimation, though actual values vary with laser type and quality; direct diode pointers often show higher divergence (around 1.5 mrad) than diode-pumped solid-state (DPSS) models due to inherent beam asymmetry in diodes.[48] Collimation is achieved through refractive optics, primarily aspherical or multi-element lenses placed at the focal length from the laser diode facet to render diverging output rays parallel. For edge-emitting diode lasers, common in red pointers, the beam is elliptical and astigmatic— with divergence in the fast axis (perpendicular to the junction) exceeding 30° and slow axis around 10°, compared to the near-90° perpendicular emission angle—necessitating initial collimation in each axis, often via separate cylindrical lenses or an anamorphic prism pair for circularization.[49] In DPSS green pointers, intracavity optics including frequency-doubling crystals (e.g., KTP) and resonator mirrors further shape the beam, yielding superior quality with divergence as low as 0.2° in high-end units, though output remains fundamentally limited by diffraction.[1] The resulting beam waist diameter at the aperture is usually 0.5 to 2 mm, with propagation governed by Gaussian beam optics where the radius , being the Rayleigh range.[50] Beam quality is quantified by the factor, which compares the beam parameter product (waist size times divergence half-angle) to an ideal Gaussian beam (); diode-based pointers typically exhibit values of 1.1 to 1.7 due to multimode operation and waveguide effects, while DPSS systems approach 1.2 or lower, enabling tighter focus and less divergence for equivalent power.[51] Empirical measurements confirm that poor optics in low-cost pointers can inflate effective divergence beyond specifications, but standards-compliant devices prioritize minimal to maximize pointing range and visibility. Atmospheric scattering and absorption introduce additional beam attenuation, but the intrinsic optics ensure the beam remains diffraction-limited far from the source.[52]Components and manufacturing trends

A typical direct-diode laser pointer incorporates a semiconductor laser diode emitting in the visible spectrum, such as 635 nm red or 532 nm green equivalents via frequency conversion, paired with a collimating lens to produce a coherent beam, a constant-current driver circuit to stabilize output, one or more button-cell batteries (e.g., AAA or CR2 lithium), and an anodized aluminum or brass housing with integrated on/off switch for portability and heat dissipation.[53][54] The diode, often a TO-5 or 5.6 mm package, generates milliwatts of power, while optics like aspheric lenses ensure beam divergence under 1 mrad for pointing distances up to 100 meters.[55] Diode-pumped solid-state (DPSS) variants, prevalent in green pointers, add complexity with an 808 nm infrared pump diode exciting a neodymium-doped crystal (e.g., Nd:YVO4) to lase at 1064 nm, followed by a potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) crystal for intracavity frequency doubling to 532 nm, all encased in a temperature-controlled module with dichroic mirrors and Q-switching elements in higher-power units.[56] These assemblies mitigate the absence of efficient direct green diodes, though they introduce stray infrared leakage up to 10 times the visible intensity in low-cost models, necessitating IR filters for safety.[57] Manufacturing has shifted to high-volume semiconductor fabrication, primarily in China, where established cleanroom infrastructure enables diode yields exceeding 90% for wavelengths like 450 nm blue and 520 nm green, reducing unit costs below $1 for basic emitters.[58] The Asia-Pacific region, led by China, dominates with over 50% of global laser diode production capacity, fueling pointer exports via automated assembly lines integrating pick-and-place robotics for optics and housings.[59] Global laser diode market volume grew from USD 6.59 billion in 2023 to an estimated USD 9.34 billion in 2025, driven by consumer electronics demand, with pointers comprising a niche segment exhibiting 5-6% CAGR amid miniaturization to sub-10 mm diameters and integration of USB-rechargeable lithium-polymer batteries.[60][61][62] Recent trends emphasize direct-diode architectures over DPSS for blue and red pointers due to higher wall-plug efficiency (up to 30%) and simpler fabrication, while green output relies on improved DPSS modules with reduced thermal lensing via vanadate crystals; however, regulatory pressures post-2020 have curbed high-power imports, shifting production toward compliant <5 mW outputs despite black-market circumvention.[58] China's industrial laser sector, including diode components, expanded at 10.2% annually to $15.9 billion by 2024, underscoring scale economies that prioritize volume over premium quality in consumer pointers.[63]Applications

Pointing and presentation tools

Laser pointers serve as handheld devices that emit a narrow beam of coherent light to highlight specific points on screens, whiteboards, or distant objects during lectures, meetings, and presentations.[1] This non-contact method allows presenters to direct audience attention precisely without needing to approach the display surface, facilitating mobility and interaction in large venues.[64] Their adoption in educational and professional settings stems from the need for efficient visual aids beyond traditional telescoping pointers or canes, enabling emphasis on charts, slides, or diagrams from a distance.[65] Common models for presentation use operate at low power levels, typically under 5 milliwatts, classified as Class 2 or 3R lasers to minimize risks while maintaining visibility.[66] Red wavelengths around 633–690 nanometers dominate early designs due to the availability of compact diode lasers, though green pointers at 532 nanometers have gained prevalence for superior visibility in brighter environments and against varied backgrounds, as human eyes are more sensitive to green light.[66] These tools enhance engagement by allowing presenters to underscore key data points or transitions, though effective use requires steady hands to avoid erratic dots that could distract viewers.[67] In classrooms and conferences, laser pointers support interactive teaching by focusing on details in visual aids, such as anatomical models or statistical graphs, thereby aiding comprehension without physical manipulation.[68] Modern variants often integrate with wireless remotes for slide advancement, combining pointing functionality with navigation, though standalone pointers remain valued for impromptu highlighting.[69] Despite benefits, guidelines emphasize avoiding direct eye exposure, as even low-power beams pose hazards if misdirected, prompting recommendations for training in safe handling during professional use.[3]Recreational and consumer uses

Laser pointers are commonly employed in pet entertainment, particularly for cats, where the projected dot stimulates chasing behavior and provides indoor exercise. Devices typically output 1-5 mW in red or green wavelengths to create a visible spot on floors or walls, engaging the animal's predatory instincts without physical contact.[70] However, veterinary experts caution that prolonged use can induce frustration or obsessive behaviors in cats, as the intangible target offers no resolution to the hunt, potentially leading to stress; pairing with tangible toys for "capture" is recommended to mitigate this.[71] For dogs, laser pointers are generally unsuitable, as they trigger intense prey drive without fulfillment, exacerbating anxiety rather than providing satisfaction, unlike in cats where shorter sessions may suffice.[72] In amateur astronomy, low-power green laser pointers (around 5 mW at 532 nm) serve as aids for group stargazing, enabling precise indication of constellations or planets against the night sky due to the beam's high visibility over distances up to several kilometers under clear conditions.[73] These devices facilitate shared observation without obstructing views, but require momentary activation switches to prevent accidental exposure and strict avoidance of aircraft flight paths or direct eye contact.[74] Higher-power variants (20-100 mW) have been advertised for enhanced range but increase retinal hazard risks, prompting recommendations to limit to FDA Class 2 or 3R classifications for safe recreational astronomy.[75] Other consumer applications include informal outdoor signaling or night vision-preserving pointers (e.g., red wavelengths for minimal scotopic disruption in activities like hiking or basic photography), though these overlap with utilitarian roles and carry misuse risks such as unintended reflections.[76] Empirical data from regulatory bodies highlight that recreational diversions often veer into hazards, with over 6,000 U.S. aviation incidents annually involving pointers aimed skyward, underscoring the need for responsible, low-output use confined to controlled environments.[5]Industrial, research, and military roles

In industrial settings, laser pointers enable precise alignment and positioning tasks, such as leveling pipes in construction and surveying operations. Construction workers utilize them to project straight lines and points for accurate installation of structural elements, improving efficiency over traditional methods like plumb bobs.[3] In manufacturing, these devices assist in workpiece positioning for robotic assembly by projecting laser spots to map objects and guide precision interactions, as demonstrated in studies on laser-assisted automation where spot projection enhanced accuracy in tasks like drilling and welding preparation.[77] Industrial variants often feature line or cross projections for applications in automotive and aerospace fabrication, ensuring alignment of components with tolerances below 0.1 mm.[78] In research environments, laser pointers facilitate optical alignment and experimental demonstrations. Laboratories employ them to align beam paths in interferometry and spectroscopy setups, with visible wavelengths (e.g., 532 nm green or 650 nm red) allowing quick verification of collinearity in complex optical trains.[79] They are also used in educational and investigative optics experiments to illustrate phenomena such as Rayleigh scattering and absorbance, using pointers at 405 nm, 532 nm, and 650 nm to visualize light interaction with media like air or solutions.[80] In specialized applications, low-cost pointers have enabled photochemical reductions of aryl halides under visible light, achieving reproducible yields in synthetic chemistry without high-intensity sources.[81] Military applications of laser pointers include tactical signaling, training aids, and low-level designation. These devices serve as illuminators and pointers in night operations for marking targets or landing zones, with infrared variants providing covert visibility for night-vision equipped personnel.[82] In training scenarios, they direct attention in K-9 units and simulate threat illumination for convoy security, leveraging green wavelengths for daytime visibility up to several kilometers.[83] However, their use is constrained by safety protocols due to risks of inadvertent exposure, as evidenced by regulatory emphasis on controlled deployment in operational contexts.[3]Safety and hazards

Biological effects on eyes and skin

Laser pointers, particularly those emitting visible wavelengths between 400 and 700 nm, pose significant risks to the human eye due to the eye's natural focusing mechanism, which concentrates the beam onto the retina. Direct exposure can result in photothermal damage, where absorbed energy rapidly heats retinal pigment epithelium cells, leading to protein denaturation, cell death, and formation of lesions such as macular burns.[84] Photochemical effects may also occur with prolonged exposure, generating reactive oxygen species that further damage photoreceptors and underlying tissues.[85] Symptoms following acute exposure include immediate headache, excessive tearing, floaters, and blurred vision, with potential for permanent central vision loss if the fovea is affected.[86] Clinical cases document retinal injuries from laser pointers, often in children or during misuse, with green-wavelength devices (around 532 nm) linked to deeper pigment layer disruption due to higher retinal absorption.[87] [88] For instance, exposures exceeding the maximum permissible exposure (MPE) limit—defined in ANSI Z136.1 as the level below which no observable effects occur, typically on the order of 1-5 mW/cm² for visible lasers depending on pulse duration—can cause irreversible macular holes or scarring.[89] Recovery is variable; some vision improves over months, but scotomas and reduced acuity persist in many instances.[90] Skin effects from standard laser pointers (limited to <5 mW output under regulatory classes like IEC 60825-1 Class 3R) are negligible for visible beams, as the MPE for skin exposure is substantially higher—up to 10 mW/cm² for areas over 1000 cm²—and the aversion response limits dwell time.[89] [91] No significant thermal burns or erythema are reported from compliant devices at typical distances, though higher-power illicit pointers could induce localized heating if pressed directly against skin for extended periods.[92] Unlike eyes, skin lacks focusing optics, dispersing energy over a larger area and reducing hazard potential for non-infrared wavelengths.[93]Type-specific risks and misconceptions