Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Law of war

View on Wikipedia

| International humanitarian law |

|---|

| Courts and Tribunals |

| Violations |

| Treaties |

| Related areas of law |

| Part of a series on |

| War (outline) |

|---|

|

The law of war, also referred to as international humanitarian law or the law of armed conflict, is the branch of international law relating to the conduct of war, which includes jus ad bellum (the law governing the permissibility of going to war) and jus in bello (the law applicable during war). The laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territories, occupation, and other critical terms of public international law.

Among other issues, the modern laws of war address the declarations of war; acceptance of surrender and the treatment of prisoners of war; the principles of distinction, as well as military necessity and proportionality; and the prohibition of certain weapons that cause unnecessary or excessive suffering.[1][2]

The law of war is considered distinct from other bodies of law—such as the domestic law of a particular belligerent to a conflict—which may provide additional legal limits to the conduct or justification of war.

Early sources and history

[edit]The first traces of a law of war come from the Babylonians. It is the Code of Hammurabi,[3] king of Babylon, which in 1750 B.C., explains its laws imposing a code of conduct in the event of war:

I prescribe these laws so that the strong do not oppress the weak.

An example from the Book of Deuteronomy 20:19–20 limits the amount of environmental damage, allowing only the cutting down of non-fruitful trees for use in the siege operation, while fruitful trees should be preserved for use as a food source. Similarly, Deuteronomy 21:10–14 requires that female captives who were forced to marry the victors of a war, then not desired anymore, be let go wherever they want, and requires them not to be treated as slaves nor be sold for money.

In the early 7th century, the first Sunni Muslim caliph, Abu Bakr, whilst instructing his Muslim army, laid down rules against the mutilation of corpses, killing children, women, and the elderly. He also laid down rules against environmental harm to trees and slaying of the enemy's animals:

Stop, O people, that I may give you ten rules for your guidance in the battlefield. Do not commit treachery or deviate from the right path. You must not mutilate dead bodies. Neither kill a child, nor a woman, nor an aged man. Bring no harm to the trees, nor burn them with fire, especially those which are fruitful. Slay not any of the enemy's flock, save for your food. You are likely to pass by people who have devoted their lives to monastic services; leave them alone.[4][5]

In the history of the early Christian church, many Christian writers considered that Christians could not be soldiers or fight wars. Augustine of Hippo contradicted this and wrote about 'just war' doctrine, in which he explained the circumstances when war could or could not be morally justified.

In 697, Adomnan of Iona gathered Kings and church leaders from around Ireland and Scotland to Birr, where he gave them the 'Law of the Innocents', which banned killing women and children in war, and the destruction of churches.[6]

Apart from chivalry in medieval Europe, the Roman Catholic Church also began promulgating teachings on just war, reflected to some extent in movements such as the Peace and Truce of God. The impulse to restrict the extent of warfare, and especially protect the lives and property of non-combatants continued with Hugo Grotius and his attempts to write laws of war.

Modern sources

[edit]

The modern law of war is made up from three principal sources:[7]

- Lawmaking treaties (or conventions)—see § International treaties on the laws of war below.

- Custom. Not all the law of war derives from or has been incorporated in such treaties, which can refer to the continuing importance of customary law as articulated by the Martens Clause. Such customary international law is established by the general practice of nations together with their acceptance that such practice is required by law.

- General Principles. "Certain fundamental principles provide basic guidance. For instance, the principles of distinction, proportionality, and necessity, all of which are part of customary international law, always apply to the use of armed force."[7]

Positive international humanitarian law consists of treaties (international agreements) that directly affect the laws of war by binding consenting nations and achieving widespread consent.

The opposite of positive laws of war is customary laws of war,[7] many of which were explored at the Nuremberg War Trials. These laws define both the permissive rights of states as well as prohibitions on their conduct when dealing with irregular forces and non-signatories.

The Treaty of Armistice and Regularization of War signed on November 25 and 26, 1820 between the president of the Republic of Colombia, Simón Bolívar and the Chief of the Military Forces of the Spanish Kingdom, Pablo Morillo, is the precursor of the International Humanitarian Law.[8] The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed and ratified by the United States and Mexico in 1848, articulates rules for any future wars, including protection of civilians and treatment of prisoners of war.[9] The Lieber Code, promulgated by the Union during the American Civil War, was critical in the development of the laws of land warfare.[10]

Historian Geoffrey Best called the period from 1856 to 1909 the law of war's "epoch of highest repute."[11] The defining aspect of this period was the establishment, by states, of a positive legal or legislative foundation (i.e., written) superseding a regime based primarily on religion, chivalry, and customs.[12] It is during this "modern" era that the international conference became the forum for debate and agreement between states and the "multilateral treaty" served as the positive mechanism for codification.

The Nuremberg War Trial judgment on "The Law Relating to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity"[13] held, under the guidelines Nuremberg Principles, that treaties like the Hague Convention of 1907, having been widely accepted by "all civilised nations" for about half a century, were by then part of the customary laws of war and binding on all parties whether the party was a signatory to the specific treaty or not.

Interpretations of international humanitarian law change over time and this also affects the laws of war. For example, Carla Del Ponte, the chief prosecutor for the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia pointed out in 2001 that although there is no specific treaty ban on the use of depleted uranium projectiles, there is a developing scientific debate and concern expressed regarding the effect of the use of such projectiles and it is possible that, in future, there may be a consensus view in international legal circles that use of such projectiles violates general principles of the law applicable to use of weapons in armed conflict.[14]

Purposes

[edit]It has often been commented that creating laws for something as inherently lawless as war seems like a lesson in absurdity. But based on the adherence to what amounted to customary international humanitarian law by warring parties through the ages, it was believed by many, especially after the eighteenth century, that codifying laws of war would be beneficial.[15] Classifications of what kind of conflict is taking place is also important. Depending on how a conflict is classified certain actors may or may not use force against another power. This can lead to tactical classification of a conflict so that one actor has the sole right of force. Sometimes a new body of law is even created to do so.[16]

Some of the central principles underlying laws of war are:[citation needed]

- Wars should be limited to achieving the political goals that started the war (e.g., territorial control) and should not include unnecessary destruction.

- Wars should be brought to an end as quickly as possible.

- People and property that do not contribute to the war effort should be protected against unnecessary destruction and hardship.

To this end, laws of war are intended to mitigate the hardships of war by:

- Protecting both combatants and protected non-combatants from unnecessary suffering.

- Safeguarding certain fundamental human rights of protected persons who fall into the hands of the enemy, particularly prisoners of war, the wounded and sick, children, and protected civilians.

- Facilitating the restoration of peace.

The idea that there is a right to war concerns, on the one hand, the jus ad bellum, the right to make war or to enter war, assuming a motive such as to defend oneself from a threat or danger, presupposes a declaration of war that warns the adversary: war is a loyal act, and on the other hand, jus in bello, the law of war, the way of making war, which involves behaving as soldiers invested with a mission for which all violence is not allowed. In any case, the very idea of a right to war is based on an idea of war that can be defined as an armed conflict, limited in space, limited in time, and by its objectives. War begins with a declaration (of war), ends with a treaty (of peace) or surrender agreement, an act of sharing, etc.[17] Laws of war serve the conflicts that are currently taking place. As conflicts change over time so do the laws that govern them. New laws can therefore be created. This is recently seen in the "assassination policies" adopted during the "War on Terror".[18]

Principles

[edit]

Military necessity, along with distinction, proportionality, humanity (sometimes called unnecessary suffering), and honor (sometimes called chivalry) are the five most commonly cited principles of international humanitarian law governing the legal use of force in an armed conflict.

Military necessity is governed by several constraints: an attack or action must be intended to help in the defeat of the enemy; it must be an attack on a legitimate military objective,[19] and the harm caused to protected civilians or civilian property must be proportional and not excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated.[20]

Distinction is a principle under international humanitarian law governing the legal use of force in an armed conflict, whereby belligerents must distinguish between combatants and protected civilians.[a][21]

Proportionality is a principle under international humanitarian law governing the legal use of force in an armed conflict, whereby belligerents must make sure that the harm caused to protected civilians or civilian property is not excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage expected by an attack on a legitimate military objective.[20] However, as Robbie Sabel, Professor of international law at the Hebrew University, who has written on this topic, notes: “Anyone with experience in armed conflict knows that you want to hit the enemy’s forces harder than they hit you… if you are attacked with a rifle, there is no rule that stipulates that you can only shoot back with a rifle, but using a machine gun would not be fair, or that if you are attacked with only one tank you cannot shoot back with two.”[22]

Humanity is a principle based on the 1907 Hague Convention IV - The Laws and Customs of War on Land restrictions against using arms, projectiles, or materials calculated to cause suffering or injury manifestly disproportionate to the military advantage realized by the use of the weapon for legitimate military purposes. In some countries, weapons are reviewed prior to their use in combat to determine if they comply with the law of war and are not designed to cause unnecessary suffering when used in their intended manner. This principle also prohibits using an otherwise lawful weapon in a manner that causes unnecessary suffering.[23]

Honor is a principle that demands a certain amount of fairness and mutual respect between adversaries. Parties to a conflict must accept that their right to adopt means of injuring each other is not unlimited, they must refrain from taking advantage of the adversary's adherence to the law by falsely claiming the law's protections, and they must recognize that they are members of a common profession that fights not out of personal hostility but on behalf of their respective States.[23]

Substantive examples

[edit]To fulfill the purposes noted above, the laws of war place substantive limits on the lawful exercise of a belligerent's power. Generally speaking, the laws require that belligerents refrain from employing violence that is not reasonably necessary for military purposes and that belligerents conduct hostilities with regard for the principles of humanity and chivalry.

However, because the laws of war are based on consensus (as the nature of international law often relies on self-policing by individual states), the content and interpretation of such laws are extensive, contested, and ever-changing.[24]

The following are particular examples of some of the substance of the laws of war, as those laws are interpreted today.

Declaration of war

[edit]Section III of the Hague Convention of 1907 required hostilities to be preceded by a reasoned declaration of war or by an ultimatum with a conditional declaration of war.

Some treaties, notably the United Nations Charter (1945) Article 2,[25] and other articles in the Charter, seek to curtail the right of member states to declare war; as does the older Kellogg–Briand Pact of 1928 for those nations who ratified it.[26] These have led to fewer modern armed conflicts being preceded by formal declarations of war, undermining the objectives of the Hague Convention.

Lawful conduct of belligerent actors

[edit]Modern laws of war regarding conduct during war (jus in bello), such as the 1949 Geneva Conventions, provide that it is unlawful for belligerents to engage in combat without meeting certain requirements. Article 4(a)(2) of the Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War recognizes Lawful Combatants by the following characteristics:

- (a) That of being commanded by a person responsible for his subordinates;

- (b) That of having a fixed distinctive sign recognizable at a distance;

- (c) That of carrying arms openly; and

- (d) That of conducting their operations in accordance with the laws and customs of war.[27]

Impersonating enemy combatants by wearing the enemy's uniform is possibly allowed, however the issue is unsettled. Fighting in that uniform is unlawful perfidy,[28] as is the taking of hostages.[citation needed]

Combatants also must be commanded by a responsible officer. That is, a commander can be held liable in a court of law for the improper actions of their subordinates. There is an exception to this if the war came on so suddenly that there was no time to organize a resistance, e.g. as a result of a foreign occupation.[citation needed]

People parachuting from an aircraft in distress

[edit]Modern laws of war, specifically within Protocol I additional to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, prohibits attacking people parachuting from an aircraft in distress regardless of what territory they are over. Once they land in territory controlled by the enemy, they must be given an opportunity to surrender before being attacked unless it is apparent that they are engaging in a hostile act or attempting to escape. This prohibition does not apply to the dropping of airborne troops, special forces, commandos, spies, saboteurs, liaison officers, and intelligence agents. Thus, such personnel descending by parachutes are legitimate targets and, therefore, may be attacked, even if their aircraft is in distress.

Red Cross, Red Crescent, Magen David Adom, and the white flag

[edit]

Modern laws of war, such as the 1949 Geneva Conventions, also include prohibitions on attacking doctors, ambulances or hospital ships displaying a Red Cross, a Red Crescent, Magen David Adom, Red Crystal, or other emblem related to the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. It is also prohibited to fire at a person or vehicle bearing a white flag, since that indicates an intent to surrender or a desire to communicate.[29]

In either case, people protected by the Red Cross/Crescent/Star or white flag are expected to maintain neutrality, and may not engage in warlike acts. In fact, engaging in war activities under a protected symbol is itself a violation of the laws of war known as perfidy. Failure to follow these requirements can result in the loss of protected status and make the individual violating the requirements a lawful target.[29]

Applicability to states and individuals

[edit]The law of war is binding not only upon states as such but also upon individuals and, in particular, the members of their armed forces. Parties are bound by the laws of war to the extent that such compliance does not interfere with achieving legitimate military goals. For example, they are obliged to make every effort to avoid damaging people and property not involved in combat or the war effort, but they are not guilty of a war crime if a bomb mistakenly or incidentally hits a residential area.[citation needed]

By the same token, combatants that intentionally use protected people or property as human shields or camouflage are guilty of violations of the laws of war and are responsible for damage to those that should be protected.[29]

Mercenaries

[edit]The use of contracted combatants in warfare has been an especially tricky situation for the laws of war. Some scholars claim that private security contractors appear so similar to state forces that it is unclear if acts of war are taking place by private or public agents.[30] International law has yet to come to a consensus on this issue.

Remedies for violations

[edit]During conflict, punishment for violating the laws of war may consist of a specific, deliberate and limited violation of the laws of war in reprisal.[citation needed]

After a conflict ends, any persons who have committed or ordered any breach of the laws of war, especially atrocities, may be held individually accountable for war crimes. Also, nations that signed the Geneva Conventions are required to search for, try and punish, anyone who had committed or ordered certain "grave breaches" of the laws of war. (Third Geneva Convention, Article 129 and Article 130)

Combatants who break specific provisions of the laws of war are termed unlawful combatants. Unlawful combatants who have been captured may lose the status and protections that would otherwise be afforded to them as prisoners of war, but only after a "competent tribunal" has determined that they are not eligible for POW status (e.g., Third Geneva Convention, Article 5) At that point, an unlawful combatant may be interrogated, tried, imprisoned, and even executed for their violation of the laws of war pursuant to the domestic law of their captor, but they are still entitled to certain additional protections, including that they be "treated with humanity and, in case of trial, shall not be deprived of the rights of fair and regular trial." (Fourth Geneva Convention, Article 5)

International treaties on the laws of war

[edit]List of declarations, conventions, treaties, and judgments on the laws of war:[31][32][33]

- 1856 Paris Declaration Respecting Maritime Law abolished privateering.

- 1863 United States military adopts the Lieber Code, a compilation of extant international norms on the treatment of civilians assembled by German scholar Franz Lieber.

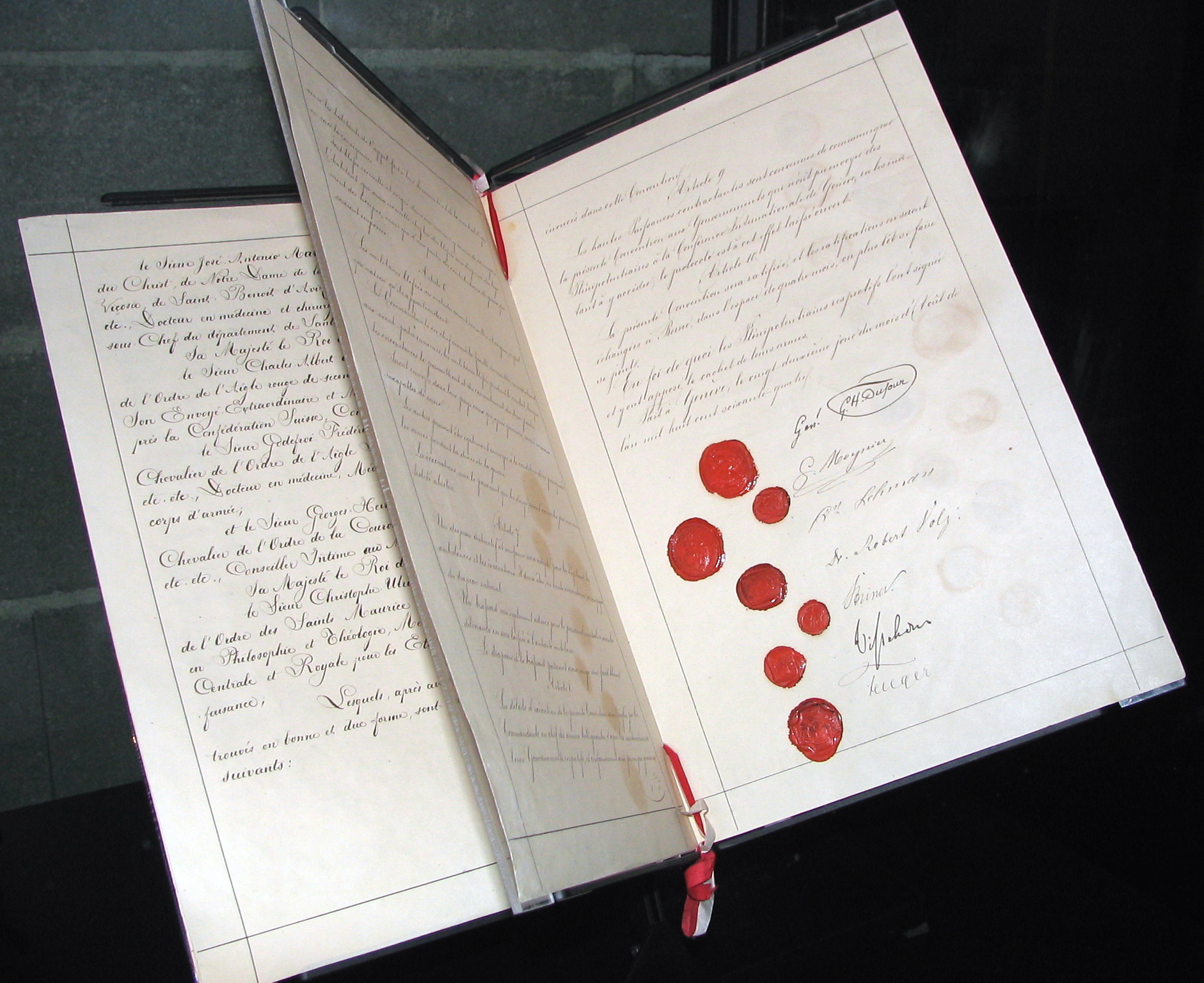

- 1864 Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field.[34]

- 1868 St. Petersburg Declaration, officially the Declaration Renouncing the Use, in Time of War, of Explosive Projectiles Under 400 Grammes Weight, renounced the usage of explosive projectiles with a mass of less than 400 grams.

- 1874 Project of an International Declaration concerning the Laws and Customs of War (Brussels Declaration).[35] Signed in Brussels 27 August. This agreement never entered into force, but formed part of the basis for the codification of the laws of war at the 1899 Hague Peace Conference.[36][37]

- 1880 Manual of the Laws and Customs of War at Oxford. At its session in Geneva in 1874 the Institute of International Law appointed a committee to study the Brussels Declaration of the same year and to submit to the Institute its opinion and supplementary proposals on the subject. The work of the Institute led to the adoption of the Manual in 1880 and it went on to form part of the basis for the codification of the laws of war at the 1899 Hague Peace Conference.[37]

- 1899 Hague Conventions consisted of three main sections and three additional declarations:

- I – Pacific Settlement of International Disputes

- II – Laws and Customs of War on Land

- III – Adaptation to Maritime Warfare of Principles of Geneva Convention of 1864

- Declaration I – On the Launching of Projectiles and Explosives from Balloons

- Declaration II – On the Use of Projectiles the Object of Which is the Diffusion of Asphyxiating or Deleterious Gases

- Declaration III – On the Use of Bullets Which Expand or Flatten Easily in the Human Body

- 1907 Hague Conventions had thirteen sections, of which twelve were ratified and entered into force, and two declarations:

- I – The Pacific Settlement of International Disputes

- II – The Limitation of Employment of Force for Recovery of Contract Debts

- III – The Opening of Hostilities

- IV – The Laws and Customs of War on Land

- V – The Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers and Persons in Case of War on Land

- VI – The Status of Enemy Merchant Ships at the Outbreak of Hostilities

- VII – The Conversion of Merchant Ships into War-ships

- VIII – The Laying of Automatic Submarine Contact Mines

- IX – Bombardment by Naval Forces in Time of War

- X – Adaptation to Maritime War of the Principles of the Geneva Convention

- XI – Certain Restrictions with Regard to the Exercise of the Right of Capture in Naval War

- XII – The Creation of an International Prize Court [Not Ratified]*

- XIII – The Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers in Naval War

- Declaration I – extending Declaration II from the 1899 Conference to other types of aircraft

- Declaration II – on the obligatory arbitration

- 1909 London Declaration concerning the Laws of Naval War largely reiterated existing law, although it showed greater regard to the rights of neutral entities. Never went into effect.

- 1922 The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty (6 February)

- 1923 Hague Draft Rules of Aerial Warfare. Never adopted in a legally binding form.[38]

- 1925 Geneva Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare.[39]

- 1927–1930 Greco-German arbitration tribunal

- 1928 General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy (also known as the Pact of Paris or Kellogg-Briand Pact)

- 1929 Geneva Convention, Relative to the treatment of prisoners of war.

- 1929 Geneva Convention on the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field,

- 1930 Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament (22 April)

- 1935 Roerich Pact

- 1936 Second London Naval Treaty (25 March)

- 1938 Amsterdam Draft Convention for the Protection of Civilian Populations Against New Engines of War. (Officially the Draft Convention for the Protection of Civilian Populations Against New Engines of War. Amsterdam, 1938). This convention was never ratified.[40]

- 1938 League of Nations declaration for the "Protection of Civilian Populations Against Bombing From the Air in Case of War[41]

- 1945 United Nations Charter (entered into force on October 24, 1945)

- 1946 Judgment of the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg

- 1947 Nuremberg Principles formulated under UN General Assembly Resolution 177, 21 November 1947

- 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

- 1949 Geneva Conventions

- Geneva Convention I for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field

- Geneva Convention II for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea

- Geneva Convention III Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War

- Geneva Convention IV Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War

- 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict

- 1971 Zagreb Resolution of the Institute of International Law on Conditions of Application of Humanitarian Rules of Armed Conflict to Hostilities in which the United Nations Forces May be Engaged

- 1974 United Nations Declaration on the Protection of Women and Children in Emergency and Armed Conflict

- 1977 United Nations Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques

- 1977 Geneva Protocol I Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (IACs)

- 1977 Geneva Protocol II Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts (NIACs)

- 1978 Red Cross Fundamental Rules of International Humanitarian Law Applicable in Armed Conflicts

- 1980 United Nations Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons Which May be Deemed to be Excessively Injurious or to Have Indiscriminate Effects (CCW)

- 1980 Protocol I on Non-Detectable Fragments

- 1980 Protocol II on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps and Other Devices

- 1980 Protocol III on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Incendiary Weapons

- 1995 Protocol IV on Blinding Laser Weapons

- 1996 Amended Protocol II on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps and Other Devices

- Protocol on Explosive Remnants of War (Protocol V to the 1980 Convention), 28 November 2003 (entered into force 12 November 2006)[42]

- 1994 San Remo Manual on International Law Applicable to Armed Conflicts at Sea[43]

- 1994 ICRC/UNGA Guidelines for Military Manuals and Instructions on the Protection of the Environment in Time of Armed Conflict[44]

- 1994 UN Convention on the Safety of United Nations and Associated Personnel.[45]

- 1996 The International Court of Justice advisory opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons

- 1997 Ottawa Treaty - Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction

- 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (entered into force 1 July 2002)

- 2000 Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict (entered into force 12 February 2002)

- 2005 Geneva Protocol III Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Adoption of an Additional Distinctive Emblem

- 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions (entered into force 1 August 2010)

- 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (entered into force 22 January 2021)

See also

[edit]- Arms control – Term for international restriction of weapons (includes list of treaties)

- Command responsibility – Doctrine of hierarchical accountability

- Crimes against humanity – Concept in international law

- Customary international humanitarian law – Body of unwritten rules

- Debellatio – War ending in defeated nation ceasing to exist

- International law – Norms in international relations

- Islamic military jurisprudence – Islamic laws of war

- Journal of International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict – Journal of the Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict

- Jus post bellum – "Justice after war"

- Law of occupation – Occupation and the laws of war

- Law of the Sea – International law concerning maritime environments

- Lawfare – Weaponization of legal systems

- Lex pacificatoria – Concept in international relations

- List of Articles of War – War regulations

- List of weapons of mass destruction treaties

- Right of conquest – Concept in political science

- Rule of Law in Armed Conflicts Project (RULAC) – International law initiative

- Self-defence in international law

- Targeted killing – Extrajudicial assassination by governments

- Total war – Conflict in which all of a nation's resources are deployed

Notes

[edit]- ^ Protected civilian in this instance means civilians who are enemy nationals or neutral citizens whose presence is outside the territory of a belligerent nation. Article 51.3 of Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions explains that "Civilians shall enjoy the protection afforded by this section, unless and for such time as they take a direct part in hostilities".

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "What is IHL?" (PDF). 2013-12-30. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-12-30. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ United States; Department of Defense; Office of General Counsel (2016). Department of Defense law of war manual. OCLC 1045636386.

- ^ "1999-01". cref.u-bordeaux4.fr. Archived from the original on 2006-03-09. Retrieved 2023-10-22.

- ^ Al-Muwatta; Book 21, Number 21.3.10.

- ^ Aboul-Enein, H. Yousuf and Zuhur, Sherifa, Islamic Rulings on Warfare, p. 22, Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, Diane Publishing Co., Darby PA, ISBN 1-4289-1039-5

- ^ Adomnan of Iona. Life of St. Columba, Penguin Books, 1995.

- ^ a b c "What is IHL?" (PDF). 2013-12-30. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-12-30. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ "Publicaciones Defensa". Publicaciones Defensa. Retrieved 2019-03-07.

- ^ "Avalon Project - Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo; February 2, 1848". Avalon.law.yale.edu. Retrieved 2019-03-07.

- ^ See, e.g., Doty, Grant R. (1998). "THE UNITED STATES AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE LAWS OF LAND WARFARE" (PDF). Military Law Review. 156: 224. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 18, 2006.

- ^ GEOFFREY BEST, HUMANITY IN WARFARE 129 (1980).

- ^ 2 L. OPPENHEIM, INTERNATIONAL LAW §§ 67–69 (H. Lauterpacht ed., 7th ed. 1952).

- ^ Judgement : The Law Relating to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity Archived 2016-09-08 at the Wayback Machine contained in the Avalon Project archive at Yale Law School.

- ^ "The Final Report to the Prosecutor by the Committee Established to Review the NATO Bombing Campaign Against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia: Use of Depleted Uranium Projectiles". Un.org. 2007-03-05. Archived from the original on August 16, 2000. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

- ^ Dunant, Henry; Dunant, Henry; Dunant, Henry (1986). A Memory of Solferino (Repr ed.). Geneva: International Committee of the Red Cross. ISBN 978-2-88145-006-8.

- ^ Erakat, Noura (2019). Justice for some: law and the question of Palestine. Stanford (Calif.): Stanford University Press. pp. 179+181. ISBN 978-0-8047-9825-9.

- ^ Stahn, C. (2006-11-01). "'Jus ad bellum', 'jus in bello' . . . 'jus post bellum'? -Rethinking the Conception of the Law of Armed Force". European Journal of International Law. 17 (5): 921–943. doi:10.1093/ejil/chl037. ISSN 0938-5428.

- ^ Erakat, Noura (2019). Justice for some: law and the question of Palestine. Stanford (Calif.): Stanford University Press. pp. 187–194. ISBN 978-0-8047-9825-9.

- ^ Article 52 of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions provides a widely accepted definition of military objective: "In so far as objects are concerned, military objectives are limited to those objects which by their nature, location, purpose or use make an effective contribution to military action and whose total or partial destruction, capture or neutralization, in the circumstances ruling at the time, offers a definite military advantage." (Source: Moreno-Ocampo 2006, page 5, footnote 11).

- ^ a b Moreno-Ocampo 2006, See section "Allegations concerning War Crimes" Pages 4,5.

- ^ Greenberg 2011, Illegal Targeting of Civilians.

- ^ Sabel, Robbie (December 18, 2023). "International Law and the Conflict in Gaza". Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs. 17 (3): 260–264. doi:10.1080/23739770.2023.2289272.

- ^ a b "Basic Principles of the Law Of War and Their Targeting Implications" (PDF). Curtis E. LeMay Center. US Air Force. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-11-01. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jefferson D. Reynolds. "Collateral Damage on the 21st century battlefield: Enemy exploitation of the law of armed conflict, and the struggle for a moral high ground". Air Force Law Review Volume 56, 2005(PDF) Page 57/58 "if international law is not enforced, persistent violations can conceivably be adopted as customary practice, permitting conduct that was once prohibited"

- ^ "Charter of the United Nations, Chapter 1". United Nations. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ See certified true copy of the text of the treaty in League of Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 94, p. 57 (No. 2137).

- ^ "Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, 75 U.N.T.S. 135". University of Minnesota Human Rights Library. United Nations. 1950-09-21. Retrieved 2021-09-12.

- ^ "Rule 62. Improper Use of the Flags or Military Emblems, Insignia or Uniforms of the Adversary". ihl-databases.icrc.org. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

However, their employment is forbidden during a combat, that is, the opening of fire whilst in the guise of the enemy. But there is no unanimity as to whether the uniform of the enemy may be worn and his flag displayed for the purpose of approach or withdrawal.

- ^ a b c Forsythe, David (2019-06-26), "International Committee of the Red Cross", International Law, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/obo/9780199796953-0183, ISBN 978-0-19-979695-3, retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ^ Phelps, Martha Lizabeth (December 2014). "Doppelgangers of the State: Private Security and Transferable Legitimacy". Politics & Policy. 42 (6): 824–849. doi:10.1111/polp.12100.

- ^ Roberts & Guelff 2000.

- ^ ICRC Treaties & Documents by date.

- ^ Phillips, Joan T. (May 2006). "List of documents and web links relating to the law of armed conflict in air and space operations". au.af.mil. Alabama: Bibliographer, Muir S. Fairchild Research Information Center Maxwell (United States) Air Force Base. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012.

- ^ "Treaties, States parties, and Commentaries - Geneva Convention, 1864". ihl-databases.icrc.org.

- ^ "The project of an International Declaration concerning the Laws and Customs of War". Brussels. 27 August 1874 – via ICRC.org.

- ^ "Brussels Conference of 1874 – International Declaration Concerning Laws and Customs of War". sipri.org. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute Project on Chemical and Biological Warfare. Archived from the original on 2007-07-11.

- ^ a b Brussels Conference of 1874 ICRC cites D. Schindler and J. Toman, The Laws of Armed Conflicts, Martinus Nihjoff Publisher, 1988, pp. 22–34.

- ^ The Hague Rules of Air Warfare, 1922–12 to 1923–02, this convention was never adopted (backup site).

- ^ Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare. Geneva, 17 June 1925.

- ^ "Draft Convention for the Protection of Civilian Populations Against New Engines of War". Amsterdam – via ICRC.org. The meetings of forum were from 29.08.1938 until 02.09.1938 in Amsterdam.

- ^ "Protection of Civilian Populations Against Bombing From the Air in Case of War". Unanimous resolution of the League of Nations Assembly. 30 September 1938.

- ^ "International Committee of the Red Cross". ICRC.org. International Committee of the Red Cross. 3 October 2013.

- ^ Doswald-Beck, Louise (31 December 1995). "San Remo Manual on International Law Applicable to Armed Conflict at Sea". International Review of the Red Cross. pp. 583–594. Archived from the original on 4 June 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2006 – via ICRC.org.

- ^ "Guidelines for Military Manuals and Instructions on the Protection of the Environment in Times of Armed Conflict". International Review of the Red Cross. 30 April 1996. pp. 230–237. Archived from the original on 16 November 2006. Retrieved 12 November 2006 – via ICRC.org.

- ^ "Convention on the Safety of United Nations and Associated Personnel". UN.org. 1995-12-31. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

General sources

[edit]- Greenberg, Joel (2011), "Illegal Targeting of Civilians", www.crimesofwar.org, archived from the original on 2013-07-06, retrieved 4 July 2013

- Johnson, James Turner (198), Just War Tradition and the Restraint of War: A Moral and Historical Inquiry, New Jersey: Princeton University Press

- Lamb, A. (2013), Ethics and the Laws of War: The moral justification of legal norms, Routledge

- Moreno-Ocampo, Luis (9 February 2006), OTP letter to senders re Iraq (PDF), International Criminal Court

- Moseley, Alex (2009), "Just War Theory", The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Roberts, Adam; Guelff, Richard, eds. (2000), Documents on the Laws of War (Third ed.), Oxford University press, ISBN 978-0-19-876390-1

- Texts and commentaries of 1949 Geneva Conventions & Additional Protocols

- Walzer, Michael (1997), Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations (2nd ed.), New York: Basic Books, archived from the original on 2011-09-10

Further reading

[edit]- Witt, John Fabian. Lincoln's Code: The Laws of War in American History (Free Press; 2012) 498 pages; on the evolution and legacy of a code commissioned by President Lincoln in the Civil War

External links

[edit]- War & law index Archived 2014-08-15 at the Wayback Machine—International Committee of the Red Cross website

- International Law of War Association

- The European Institute for International Law and International Relations

- The Rule of Law in Armed Conflicts Project

- Law of War Manual, U.S. Department of Defense (2015, updated December 2016)