Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hepatocyte

View on Wikipedia| Hepatocyte | |

|---|---|

| |

Human liver stained with hematoxylin and eosin showing hepatocytes organized into plates and lobules | |

| Details | |

| Location | Liver |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D022781 |

| TH | H3.04.05.0.00006 |

| FMA | 14515 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

A hepatocyte is a cell of the main parenchymal tissue of the liver. Hepatocytes make up 80% of the liver's mass. These cells are involved in:

- Protein synthesis

- Protein storage

- Transformation of carbohydrates

- Synthesis of cholesterol, bile salts and phospholipids

- Detoxification, modification, and excretion of exogenous and endogenous substances

- Initiation of formation and secretion of bile

Structure

[edit]The typical hepatocyte is cubical with sides of 20–30 μm, (in comparison, a human hair has a diameter of 17 to 180 μm).[1] The typical volume of a hepatocyte is 3.4 x 10−9 cm3.[2] Smooth endoplasmic reticulum is abundant in hepatocytes, in contrast to most other cell types.[3]

Microanatomy

[edit]Hepatocytes display an eosinophilic cytoplasm, reflecting numerous mitochondria, and basophilic stippling due to large amounts of rough endoplasmic reticulum and free ribosomes. Brown lipofuscin granules are also observed (with increasing age) together with irregular unstained areas of cytoplasm; these correspond to cytoplasmic glycogen and lipid stores removed during histological preparation. The average life span of the hepatocyte is 5 months; they are able to regenerate.[citation needed]

Hepatocyte nuclei are round with dispersed chromatin and prominent nucleoli. Anisokaryosis (or variation in the size of the nuclei) is common and often reflects tetraploidy and other degrees of polyploidy, a normal feature of 30–40% of hepatocytes in the adult human liver.[4] Binucleate cells are also common.[citation needed]

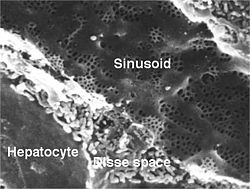

Hepatocytes are organised into plates separated by vascular channels (sinusoids), an arrangement supported by a reticulin (collagen type III) network. The hepatocyte plates are one cell thick in mammals and two cells thick in the chicken. Sinusoids display a discontinuous, fenestrated endothelial cell lining. The endothelial cells have no basement membrane and are separated from the hepatocytes by the space of Disse, which drains lymph into the portal tract lymphatics.[citation needed]

Kupffer cells are scattered between endothelial cells; they are part of the reticuloendothelial system and phagocytose spent erythrocytes. Stellate (Ito) cells store vitamin A and produce extracellular matrix and collagen; they are also distributed amongst endothelial cells but are difficult to visualise by light microscopy.[citation needed]

Function

[edit]Protein synthesis

[edit]The hepatocyte is a cell in the body that manufactures serum albumin, fibrinogen, and the prothrombin group of clotting factors (except for Factors 3 and 4).[citation needed]

It is the main site for the synthesis of lipoproteins, ceruloplasmin, transferrin, complement, and glycoproteins. Hepatocytes manufacture their own structural proteins and intracellular enzymes.[citation needed]

Synthesis of proteins is by the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER), and both the rough and smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER) are involved in secretion of the proteins formed.[citation needed]

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is involved in conjugation of proteins to lipid and carbohydrate moieties synthesized by, or modified within, the hepatocytes.[5]

Proteins produced by hepatocytes that function as hormones are known as hepatokines.[citation needed]

Carbohydrate metabolism

[edit]The liver forms fatty acids from carbohydrates and synthesizes triglycerides from fatty acids and glycerol.[6] Hepatocytes also synthesize apoproteins with which they then assemble and export lipoproteins (VLDL, HDL).[citation needed]

The liver is also the main site in the body for gluconeogenesis, the formation of carbohydrates from precursors such as alanine, glycerol, and oxaloacetate.[citation needed]

Lipid metabolism

[edit]The liver receives many lipids from the systemic circulation and metabolizes chylomicron remnants. It also synthesizes cholesterol from acetate and further synthesizes bile salts. The liver is the sole site of bile salts formation.[citation needed]

Detoxification

[edit]Hepatocytes have the ability to metabolize, detoxify, and inactivate exogenous compounds such as drugs (see drug metabolism), insecticides, and endogenous compounds such as steroids.[citation needed]

The drainage of the intestinal venous blood into the liver requires efficient detoxification of miscellaneous absorbed substances to maintain homeostasis and protect the body against ingested toxins.[citation needed]

One of the detoxifying functions of hepatocytes is to modify ammonia into urea for excretion.[citation needed]

The most abundant organelle in liver cells is the smooth endoplasmic reticulum.[citation needed]

Aging

[edit]As mammalian liver cells age, damages in their DNA increase in prevalence. A review of the literature indicated that in mouse liver cells DNA damages (single-strand breaks, oxidized bases and 7-methylguanine) increase with age.[7] Also, in rat liver, DNA single- and double-strand breaks, oxidized bases, and methylated bases increase with age; and in rabbit liver, cross-linked bases increase with age.[7] Liver cells depend on DNA repair pathways that specifically protect the transcribed compartment of the genome to promote sustained functionality and cell preservation with age.[8]

Society and culture

[edit]Use in research

[edit]Primary hepatocytes are commonly used in cell biological and biopharmaceutical research. In vitro model systems based on hepatocytes have been of great help to better understand the role of hepatocytes in (patho)physiological processes of the liver. In addition, pharmaceutical industry has heavily relied on the use of hepatocytes in suspension or culture to explore mechanisms of drug metabolism and even predict in vivo drug metabolism. For these purposes, hepatocytes are usually isolated from animal or human[9] whole liver or liver tissue by collagenase digestion, which is a two-step process. In the first step, the liver is placed in an isotonic solution, in which calcium is removed to disrupt cell-cell tight junctions by the use of a calcium chelating agent. Next, a solution containing collagenase is added to separate the hepatocytes from the liver stroma. This process creates a suspension of hepatocytes, which can be seeded in multi-well plates and cultured for many days or even weeks. For optimal results, culture plates should first be coated with an extracellular matrix (e.g. collagen, Matrigel) to promote hepatocyte attachment (typically within 1-3 hr after seeding) and maintenance of the hepatic phenotype. In addition, and overlay with an additional layer of extracellular matrix is often performed to establish a sandwich culture of hepatocytes. The application of a sandwich configuration supports prolonged maintenance of hepatocytes in culture.[10][11] Freshly-isolated hepatocytes that are not used immediately can be cryopreserved and stored.[12] They do not proliferate in culture. Hepatocytes are intensely sensitive to damage during the cycles of cryopreservation including freezing and thawing. Even after the addition of classical cryoprotectants there is still damage done while being cryopreserved.[13] Nevertheless, recent cryopreservation and resuscitation protocols support application of cryopreserved hepatocytes for most biopharmaceutical applications.[14]

Additional images

[edit]-

Schematic diagram of biliary system

-

Hepatocytes in cell culture

-

Schematic of hepatocyte polarization, showing proteins localized to the basolateral and apical surfaces of the hepatocyte, referred to as the sinusoidal and canalicular membranes, respectively

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ The diameter of human hair ranges from 17 to 181 μm. Ley, Brian (1999). Elert, Glenn (ed.). "Diameter of a human hair". The Physics Factbook. Retrieved 2018-12-08.

- ^ Lodish, H.; Berk, A.; Zipursky, S.L.; Matsudaira, P.; Baltimore, D.; Darnell, J.E. Molecular Cell Biology (5th ed.). W.H. Freeman. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7167-4366-8. OCLC 52092052.

- ^ Pavelka, Margit; Roth, J. (Cell and molecular pathologist) (2010). Functional ultrastructure: Atlas of tissue biology and pathology. Wien: SpringerWeinNewYork. ISBN 978-3-211-99390-3. OCLC 663096046.

- ^ Celton-Morizur, S; Merlen, G; Couton, D; Desdouets, C (1 February 2010). "Polyploidy and liver proliferation: central role of insulin signaling" (PDF). Cell Cycle. 9 (3): 460–6. doi:10.4161/cc.9.3.10542. PMID 20090410. S2CID 22708555. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25.

- ^ Zhang, LiChun; Wang, Hong-Hui (2016-07-01). "The essential functions of endoplasmic reticulum chaperones in hepatic lipid metabolism". Digestive and Liver Disease. 48 (7): 709–716. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2016.03.016. ISSN 1590-8658.

- ^ Ali ES, Hua J, Wilson CH, Tallis GA, Zhou FH, Rychkov GY, Barritt GJ (2016). "The glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue exendin-4 reverses impaired intracellular Ca2+ signalling in steatotic hepatocytes". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1863 (9): 2135–46. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.05.006. PMID 27178543.

- ^ a b Holmes GE, Bernstein C, Bernstein H (September 1992). "Oxidative and other DNA damages as the basis of aging: a review". Mutat Res. 275 (3–6): 305–15. doi:10.1016/0921-8734(92)90034-m. PMID 1383772.

- ^ Vougioukalaki M, Demmers J, Vermeij WP, Baar M, Bruens S, Magaraki A, Kuijk E, Jager M, Merzouk S, Brandt RM, Kouwenberg J, van Boxtel R, Cuppen E, Pothof J, Hoeijmakers JH (April 2022). "Different responses to DNA damage determine ageing differences between organs". Aging Cell. 21 (4) e13562. doi:10.1111/acel.13562. PMC 9009128. PMID 35246937.

- ^ Lecluyse EL, Alexandre E (2010). "Isolation and culture of primary hepatocytes from resected human liver tissue". Hepatocytes. Methods Mol. Biol. Vol. 640. pp. 57–82. doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-688-7_3. ISBN 978-1-60761-687-0. PMID 20645046.

- ^ Dunn JC, Yarmush ML, Koebe HG, Tompkins RG (Feb 1989). "Hepatocyte function and extracellular matrix geometry: long-term culture in a sandwich configuration". FASEB J. 3 (2): 174–7. doi:10.1096/fasebj.3.2.2914628. PMID 2914628. S2CID 449420. Erratum in: FASEB J 1989 May;3(7):1873.

- ^ De Bruyn T, Chatterjee S, Fattah S, Keemink J, Nicolaï J, Augustijns P, Annaert P (May 2013). "Sandwich-cultured hepatocytes: utility for in vitro exploration of hepatobiliary drug disposition and drug-induced hepatotoxicity". Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 9 (5): 589–616. doi:10.1517/17425255.2013.773973. PMID 23452081. S2CID 27593521.

- ^ Li Albert P (2001). "Screening for human ADME/Tox drug properties in Drug Discovery". Drug Discovery Today. 6 (7): 357–366. doi:10.1016/s1359-6446(01)01712-3. PMID 11267922.

- ^ Hamel, F.; Grondin, M. L.; Denizeau, F.; Averill-Bates, D. A.; Sarhan, F. (2006). "Wheat extracts as an efficient cryoprotective agent for primary cultures of rat hepatocytes". Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 95 (4): 661–670. doi:10.1002/bit.20953. PMID 16927246. S2CID 4981423.

- ^ De Bruyn T, Ye ZW, Peeters A, Sahi J, Baes M, Augustijns PF, Annaert PP (Jul 2011). "Determination of OATP-, NTCP- and OCT-mediated substrate uptake activities in individual and pooled batches of cryopreserved human hepatocytes". Eur J Pharm Sci. 43 (4): 297–307. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2011.05.002. PMID 21605667.

External links

[edit]- Histology image: 22101ooa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - "Ultrastructure of the Cell: hepatocytes and sinusoids"

- Hepatic Histology: Hepatocytes (Colorado State University Archived 2023-05-29 at the Wayback Machine