Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sideband

View on Wikipedia

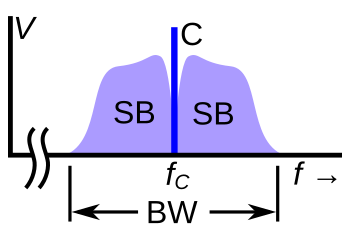

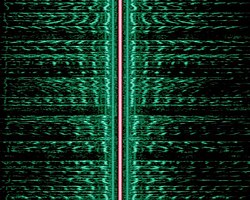

In radio communications, a sideband is a band of frequencies higher than or lower than the carrier frequency, that are the result of the modulation process. The sidebands carry the information transmitted by the radio signal. The sidebands comprise all the spectral components of the modulated signal except the carrier. The signal components above the carrier frequency constitute the upper sideband (USB), and those below the carrier frequency constitute the lower sideband (LSB). All forms of modulation produce sidebands.

Sideband creation

[edit]We can illustrate the creation of sidebands with one trigonometric identity:

Adding to both sides:

Substituting (for instance) and where represents time:

Adding more complexity and time-variation to the amplitude modulation also adds it to the sidebands, causing them to widen in bandwidth and change with time. In effect, the sidebands "carry" the information content of the signal.[1]

Sideband Characterization

[edit]In the example above, a cross-correlation of the modulated signal with a pure sinusoid, is zero at all values of except 1100, 1000, and 900. And the non-zero values reflect the relative strengths of the three components. A graph of that concept, called a Fourier transform (or spectrum), is the customary way of visualizing sidebands and defining their parameters.

Amplitude modulation

[edit]Amplitude modulation of a carrier signal normally results in two mirror-image sidebands. The signal components above the carrier frequency constitute the upper sideband (USB), and those below the carrier frequency constitute the lower sideband (LSB). For example, if a 900 kHz carrier is amplitude modulated by a 1 kHz audio signal, there will be components at 899 kHz and 901 kHz as well as 900 kHz in the generated radio frequency spectrum; so an audio bandwidth of (say) 7 kHz will require a radio spectrum bandwidth of 14 kHz. In conventional AM transmission, as used by broadcast band AM stations, the original audio signal can be recovered ("detected") by either synchronous detector circuits or by simple envelope detectors because the carrier and both sidebands are present. This is sometimes called double sideband amplitude modulation (DSB-AM), but not all variants of DSB are compatible with envelope detectors.

In some forms of AM, the carrier may be reduced, to save power. The term DSB reduced-carrier normally implies enough carrier remains in the transmission to enable a receiver circuit to regenerate a strong carrier or at least synchronise a phase-locked loop but there are forms where the carrier is removed completely, producing double sideband with suppressed carrier (DSB-SC). Suppressed carrier systems require more sophisticated circuits in the receiver and some other method of deducing the original carrier frequency. An example is the stereophonic difference (L-R) information transmitted in stereo FM broadcasting on a 38 kHz subcarrier where a low-power signal at half the 38-kHz carrier frequency is inserted between the monaural signal frequencies (up to 15 kHz) and the bottom of the stereo information sub-carrier (down to 38–15 kHz, i.e. 23 kHz). The receiver locally regenerates the subcarrier by doubling a special 19 kHz pilot tone. In another example, the quadrature modulation used historically for chroma information in PAL television broadcasts, the synchronising signal is a short burst of a few cycles of carrier during the "back porch" part of each scan line when no image is transmitted. But in other DSB-SC systems, the carrier may be regenerated directly from the sidebands by a Costas loop or squaring loop. This is common in digital transmission systems such as BPSK where the signal is continually present.

If part of one sideband and all of the other remain, it is called vestigial sideband, used mostly with television broadcasting, which would otherwise take up an unacceptable amount of bandwidth. Transmission in which only one sideband is transmitted is called single-sideband modulation or SSB. SSB is the predominant voice mode on shortwave radio other than shortwave broadcasting. Since the sidebands are mirror images, which sideband is used is a matter of convention.

In SSB, the carrier is suppressed, significantly reducing the electrical power (by up to 12 dB) without affecting the information in the sideband. This makes for more efficient use of transmitter power and RF bandwidth, but a beat frequency oscillator must be used at the receiver to reconstitute the carrier. If the reconstituted carrier frequency is wrong then the output of the receiver will have the wrong frequencies, but for speech small frequency errors are no problem for intelligibility. Another way to look at an SSB receiver is as an RF-to-audio frequency transposer: in USB mode, the dial frequency is subtracted from each radio frequency component to produce a corresponding audio component, while in LSB mode each incoming radio frequency component is subtracted from the dial frequency.

Frequency modulation

[edit]Frequency modulation also generates sidebands, the bandwidth consumed depending on the modulation index - often requiring significantly more bandwidth than DSB. Bessel functions can be used to calculate the bandwidth requirements of FM transmissions. Carson's rule is a useful approximation of bandwidth in several applications.

Effects

[edit]Sidebands can interfere with adjacent channels. The part of the sideband that would overlap the neighboring channel must be suppressed by filters, before or after modulation (often both). In broadcast band frequency modulation (FM), subcarriers above 75 kHz are limited to a small percentage of modulation and are prohibited above 99 kHz altogether to protect the ±75 kHz normal deviation and ±100 kHz channel boundaries. Amateur radio and public service FM transmitters generally utilize ±5 kHz deviation.

To accurately reproduce the modulating waveform, the entire signal processing path of the system of transmitter, propagation path, and receiver must have enough bandwidth so that enough of the sidebands can be used to recreate the modulated signal to the desired degree of accuracy.

In a non-linear system such as an amplifier, sidebands of the original signal frequency components may be generated due to distortion. This is generally minimized but may be intentionally done for the fuzzbox musical effect.

See also

[edit]- Independent sideband

- Out-of-band communications involve a channel other than the main communication channel.

- Side lobe

- Sideband computing is a distributed computing method using a channel separate from the main communication channel.

- TV transmitter

References

[edit]- ^ Tony Dorbuck (ed.), The Radio Amateur's Handbook, Fifty-Fifth Edition, American Radio Relay League, 1977, p. 368

This article incorporates public domain material from Federal Standard 1037C. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22. (in support of MIL-STD-188).

This article incorporates public domain material from Federal Standard 1037C. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22. (in support of MIL-STD-188).- Department of The Army Technical Manual TM 11-685 "Fundamentals of Single Sideband Communications"

Sideband

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Basic Concept

A sideband is a band of frequencies either above or below the carrier frequency, generated by the modulation process, containing the frequency components displaced from the carrier by multiples of the modulating frequency. These sidebands carry the information of the modulating signal.[7]Historical Development

The concept of sidebands as modulation products emerged in the late 19th century through early experiments on acoustic and electrical phenomena. In 1875, American physicist Alfred M. Mayer demonstrated the existence of sidebands experimentally by observing sidetones in telephone lines during amplitude modulation-like interactions between sound waves and electrical currents.[8] This was followed by a theoretical explanation in 1894 by Lord Rayleigh, who mathematically described sidebands as frequency components arising from the nonlinear mixing of a carrier with a modulating signal in his work on sound propagation. A major advancement came in 1915 with the work of American engineer John Renshaw Carson at AT&T, who developed the theoretical foundations for single-sideband (SSB) transmission. Carson's analysis showed that transmitting only one sideband and suppressing the carrier could achieve efficient signal transmission without loss of information, as detailed in his patent application for a method using balanced modulators to eliminate unwanted components. This laid the groundwork for bandwidth-saving techniques in telephony and radio. The 1920s saw practical implementation enabled by vacuum tube technology, which allowed reliable generation of modulated signals with distinct sidebands. Engineers like those at Bell Laboratories used triode vacuum tubes as modulators to produce and analyze sideband spectra, facilitating the first commercial applications in long-distance telephone multiplexing where multiple channels shared a single line via sideband separation. By the 1930s, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC), established in 1934, began promoting spectrum efficiency through regulations that encouraged advanced modulation practices, including SSB for international radiotelephone services to accommodate growing demand without expanding frequency allocations.[9] A key milestone in the 1940s was the adoption of vestigial sideband (VSB) modulation for television broadcasting. In 1941, the FCC approved the NTSC standard, which incorporated VSB to transmit the full upper sideband and a partial lower sideband of the video signal, optimizing the 6 MHz channel bandwidth while maintaining compatibility with receivers and reducing interference.[10] This technique became integral to analog TV systems worldwide, balancing picture quality with spectral efficiency.Generation Mechanisms

Amplitude Modulation Sidebands

In amplitude modulation (AM), the amplitude of a high-frequency carrier wave is varied in accordance with the instantaneous amplitude of a lower-frequency modulating signal, resulting in the generation of two sidebands symmetric around the carrier frequency. These sidebands appear at frequencies and , where is the carrier frequency and is the modulating frequency, effectively representing the sum and difference frequencies that encode the information from the modulating signal.[11] The mathematical representation of a conventional AM signal for a single-tone modulating signal is given bywhere is the carrier amplitude and (with ) is the modulation index, defined as the ratio of the modulating signal amplitude to the carrier amplitude.[12] This form assumes conventional double-sideband (DSB) AM, where the carrier is transmitted alongside the sidebands. To reveal the sideband components, the equation expands using the trigonometric identity :

The first term represents the unmodulated carrier, while the second and third terms correspond to the upper sideband (USB) and lower sideband (LSB), respectively, each with amplitude .[11] In the frequency domain, the spectrum of this DSB-AM signal for single-tone modulation consists of three discrete lines: the carrier at with amplitude , the USB at with amplitude , and the LSB at with amplitude . The sidebands are mirror images of each other and redundantly carry the same modulating information, which allows for envelope detection in receivers but also implies inefficiency in bandwidth usage.[12] Regarding power distribution, the carrier consumes a significant portion of the total transmitted power, with each sideband carrying half of the total sideband power. The average power of the carrier is , while the total sideband power is , assuming a normalized resistance of 1 ohm for power calculations. The overall transmission efficiency , defined as the ratio of sideband power to total power , is

This reaches a maximum of 33% at (100% modulation), highlighting the inefficiency of conventional AM due to the power wasted in the carrier, which conveys no information.[12]

Frequency Modulation Sidebands

In frequency modulation (FM), the modulating signal causes the carrier frequency to vary instantaneously, generating an infinite series of sidebands spaced at integer multiples of the modulating frequency around the carrier frequency .[13] These sidebands appear at frequencies , where is any integer, and their amplitudes depend on the modulation index , with denoting the peak frequency deviation.[14] The FM signal for a sinusoidal modulating wave can be expressed aswhere is the carrier amplitude.[14] This equation expands into a Fourier series using Bessel functions of the first kind:

with providing the relative amplitude for the -th sideband pair (noting for odd ).[13] For narrowband FM (), only the carrier and the first-order sidebands () carry significant power, yielding a spectrum similar to amplitude modulation with two prominent sidebands.[14] In contrast, wideband FM () produces numerous higher-order sidebands, where the carrier component may null at specific values (e.g., ), redistributing energy across the sidebands.[13] Carson's rule approximates the FM signal bandwidth as , capturing roughly 98% of the total power within this range.[13]

Other Modulation Types

Phase modulation (PM) is an angle modulation technique where the phase of the carrier signal is varied in proportion to the modulating signal, producing sidebands analogous to those in frequency modulation (FM). The instantaneous phase deviation is given by , where is the phase sensitivity and is the message signal, leading to a modulation index , the peak phase shift. The sideband amplitudes are determined by Bessel functions of the first kind, , where denotes the order of the sideband, resulting in a spectrum for a sinusoidal modulator.[15] PM and FM are mathematically interchangeable: an FM signal can be generated by integrating the PM modulating signal, and vice versa by differentiation, as the instantaneous frequency in PM is the derivative of the phase.[15] In digital modulation schemes such as phase-shift keying (PSK) and quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM), sidebands arise around the carrier frequency due to abrupt transitions between symbols, contrasting with the continuous modulation in analog PM or FM. The power spectral density (PSD) of these signals typically exhibits a sinc-squared shape for rectangular pulse shaping, with main lobes centered at the carrier and sidelobes decaying, featuring nulls at integer multiples of the symbol rate , where is the symbol duration.[16] This spectral structure confines most energy within a bandwidth of approximately null-to-null, enabling efficient spectrum use through pulse shaping filters like raised cosine to suppress out-of-band emissions.[16] Vestigial sideband (VSB) modulation involves partial suppression of one sideband to achieve bandwidth savings over double-sideband schemes while avoiding the complexity of full single-sideband (SSB) filtering, particularly useful for signals with significant low-frequency content like video. In VSB, a double-sideband suppressed-carrier (DSB-SC) signal passes through a filter with frequency response that passes the full lower sideband ( for ) and a tapered vestige of the upper sideband, ensuring for to minimize distortion upon demodulation.[17] This approach was employed in analog television broadcasting, such as NTSC standards, reducing the required channel bandwidth to about 1.25 times the baseband while allowing simple envelope detection at the receiver.[17] A key distinction in digital modulation sidebands, as seen in QAM and PSK, is their reduced redundancy compared to analog counterparts; the discrete symbol nature and pulse shaping concentrate energy efficiently, facilitating error-correcting codes and higher spectral efficiency without the proportional sideband power distribution of continuous analog modulation.[18]Characteristics and Analysis

Upper and Lower Sidebands

In amplitude modulation, the upper sideband (USB) refers to the band of frequencies above the carrier frequency , specifically located at where is the frequency of the modulating signal, while the lower sideband (LSB) occupies the band below at . These sidebands arise from the interaction between the carrier and the modulating waveform, carrying the informational content of the original signal translated to the carrier's vicinity.[12] For real-valued signals, the spectra of the USB and LSB exhibit Hermitian symmetry, meaning the upper sideband is the complex conjugate mirror image of the lower sideband across the carrier frequency.[19] This symmetry ensures that in double-sideband (DSB) modulation, the two sidebands are identical in their informational content, effectively duplicating the baseband message./02:_Modulation/2.04:_Analog_Modulation) Reversing the polarity of the modulating signal swaps the roles of the USB and LSB, inverting the spectral orientation relative to the carrier.[20] Due to this equivalence, the baseband signal can be fully recovered from either the USB or LSB alone via coherent demodulation in single-sideband (SSB) modulation, as each contains the complete message information.[21] In full DSB modulation, however, both sidebands are typically required for coherent detection to reconstruct the original signal amplitude without loss, as they contribute additively during demodulation./03:_Transmitters_and_Receivers/3.02:_Single-Sideband_and_Double-Sideband_Modulation) Frequencies for these sidebands are conventionally denoted in hertz (Hz) or kilohertz (kHz); for instance, modulating an audio tone at kHz onto a carrier at MHz produces a USB at 1.001 MHz and an LSB at 0.999 MHz.[22]Bandwidth and Spectrum

In amplitude modulation (AM), the bandwidth of the modulated signal is defined as the total frequency span from the lowest frequency of the lower sideband (LSB) to the highest frequency of the upper sideband (USB), which equals twice the maximum frequency component of the modulating signal, .[23] This arises because the sidebands are symmetrically placed around the carrier frequency, each mirroring the spectrum of the baseband signal. For instance, a modulating signal with frequency components up to produces sidebands extending above and below the carrier. In frequency modulation (FM), the bandwidth is approximated by Carson's rule as , where is the peak frequency deviation and is the maximum modulating frequency.[13] This rule accounts for the infinite series of sidebands in FM but captures approximately 98% of the signal power within the specified span, making it a practical estimate for system design.[24] The frequency spectrum of sidebands is analyzed using the Fourier transform, which decomposes the modulated signal into its frequency components, revealing the density and distribution of sidebands.[25] For single-tone modulation, the spectrum shows discrete lines at , but multi-tone modulation—common in complex signals like voice—spreads the sidebands into continuous bands, with the overall shape determined by the modulating signal's spectrum convolved with the carrier.[13] Key factors influencing sideband bandwidth include the modulation index ( for FM), which controls the number and amplitude of significant sidebands, and the inherent bandwidth of the modulating signal, which sets the extent of spectral replication in AM.[26] Higher modulation indices in FM generate more sidebands, expanding the effective bandwidth beyond the basic rule.[27] For a typical voice signal with a bandwidth of 300 Hz to 3 kHz, AM modulation yields a total sideband bandwidth of 6 kHz, as the sidebands replicate the full audio spectrum on either side of the carrier.[23] This example illustrates how the modulating signal's range directly dictates the transmitted spectrum's width in double-sideband AM. Occupied bandwidth is measured as the frequency interval containing 99% of the total signal power, often determined via spectrum analyzer integration of the power spectral density.[28] Alternatively, it can be assessed at points where the power falls to -26 dB relative to the peak, providing a standardized metric for regulatory compliance and interference assessment.[29]Sideband Suppression Techniques

Single-sideband (SSB) modulation suppresses one sideband and often the carrier to enhance spectral efficiency in communication systems, achieving a 50% bandwidth reduction compared to double-sideband suppressed carrier (DSB-SC) modulation./03%3A_Transmitters_and_Receivers/3.02%3A_Single-Sideband_and_Double-Sideband_Modulation) This approach concentrates transmitted power in the remaining sideband, yielding up to 100% efficiency for voice signal peaks, in contrast to conventional amplitude modulation's maximum of approximately 33%.[30] The filter method generates an SSB signal by first producing a DSB-SC waveform through balanced modulation, followed by a sharp bandpass filter to eliminate the undesired sideband.[31] Analog implementations rely on high-quality filters, such as crystal ladder designs with quality factors (Q) exceeding 100, often reaching thousands to ensure steep roll-off and minimal distortion near the passband edges.[32] In digital systems, DSP-based filtering enables precise suppression exceeding 40 dB, leveraging finite impulse response or infinite impulse response algorithms for adaptable performance. The phasing method achieves suppression by introducing a 90° phase shift to both the audio signal and carrier before balanced modulation, then adding or subtracting the resulting signals to cancel the unwanted sideband.[33] For the upper sideband, this can be formulated using the Hilbert transform aswhere is the message signal and is its Hilbert transform, effectively shifting positive frequencies by -90° and negative by +90° to isolate one sideband.[25] These techniques offer substantial power and bandwidth savings critical for efficient transmission, but inaccuracies in phase alignment or filter characteristics can introduce distortion from incomplete suppression of the unwanted sideband.[34]

![{\displaystyle \cos(A)\cdot [1+\cos(B)]={\tfrac {1}{2}}\cos(A+B)+\cos(A)+{\tfrac {1}{2}}\cos(A-B)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e74535a5163ade273c2ea320dc59dc9714790cfb)

![{\displaystyle \underbrace {\cos(1000\ t)} _{\text{carrier wave}}\cdot \underbrace {[1+\cos(100\ t)]} _{\text{amplitude modulation}}=\underbrace {{\tfrac {1}{2}}\cos(1100\ t)} _{\text{upper sideband}}+\underbrace {\cos(1000\ t)} _{\text{carrier wave}}+\underbrace {{\tfrac {1}{2}}\cos(900\ t)} _{\text{lower sideband}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/acfd1bddb1316e0f98379c1d0e558d7c3e1ad847)