Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Photophone

View on Wikipedia

The photophone is a telecommunications device that allows transmission of speech on a beam of light. It was invented jointly by Alexander Graham Bell and his assistant Charles Sumner Tainter on February 19, 1880, at Bell's laboratory at 1325 L Street NW in Washington, D.C.[1][2] Both were later to become full associates in the Volta Laboratory Association, created and financed by Bell.

On June 3, 1880, Bell's assistant transmitted a wireless voice telephone message from the roof of the Franklin School to the window of Bell's laboratory, some 213 meters (about 700 ft.) away.[3][4][5][6]

Bell believed the photophone was his most important invention. Of the 18 patents granted in Bell's name alone, and the 12 he shared with his collaborators, four were for the photophone, which Bell referred to as his "greatest achievement", telling a reporter shortly before his death that the photophone was "the greatest invention [I have] ever made, greater than the telephone".[7][8]

The photophone was a precursor to the fiber-optic communication systems that achieved worldwide popular usage starting in the 1980s.[9][10][11] The master patent for the photophone (U.S. patent 235,199 Apparatus for Signalling and Communicating, called Photophone) was issued in December 1880,[5] many decades before its principles came to have practical applications.

Design

[edit]

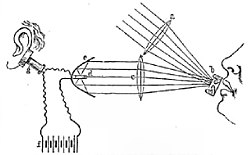

The photophone was similar to a contemporary telephone, except that it used modulated light as a means of wireless transmission while the telephone relied on modulated electricity carried over a conductive wire circuit.

Bell's own description of the light modulator:[12]

We have found that the simplest form of apparatus for producing the effect consists of a plane mirror of flexible material against the back of which the speaker's voice is directed. Under the action of the voice the mirror becomes alternately convex and concave and thus alternately scatters and condenses the light.

The brightness of a reflected beam of light, as observed from the location of the receiver, therefore varied in accordance with the audio-frequency variations in air pressure—the sound waves—which acted upon the mirror.

In its initial form, the photophone receiver was also non-electronic, using the photoacoustic effect. Bell found that many substances could be used as direct light-to-sound transducers. Lampblack proved to be outstanding. Using a fully modulated beam of sunlight as a test signal, one experimental receiver design, employing only a deposit of lampblack, produced a tone that Bell described as "painfully loud" to an ear pressed close to the device.[13]

In its ultimate electronic form, the photophone receiver used a simple selenium cell photodetector at the focus of a parabolic mirror.[5] The cell's electrical resistance (between about 100 and 300 ohms) varied inversely with the light falling upon it, i.e., its resistance was higher when dimly lit, lower when brightly lit. The selenium cell took the place of a carbon microphone—also a variable-resistance device—in the circuit of what was otherwise essentially an ordinary telephone, consisting of a battery, an electromagnetic earphone, and the variable resistance, all connected in series. The selenium modulated the current flowing through the circuit, and the current was converted back into variations of air pressure—sound—by the earphone.

In his speech to the American Association for the Advancement of Science in August 1880, Bell gave credit for the first demonstration of speech transmission by light to Mr. A.C. Brown of London in the Fall of 1878.[5][14]

Because the device used radiant energy, the French scientist Ernest Mercadier suggested that the invention should not be named 'photophone', but 'radiophone', as its mirrors reflected the Sun's radiant energy in multiple bands including the invisible infrared band.[15] Bell used the name for a while but it should not be confused with the later invention "radiophone" which used radio waves.[16]

First successful wireless voice communications

[edit]

While honeymooning in Europe with his bride Mabel Hubbard, Bell likely read of the newly discovered property of selenium having a variable resistance when acted upon by light, in a paper by Robert Sabine as published in Nature on 25 April 1878. In his experiments, Sabine used a meter to see the effects of light acting on selenium connected in a circuit to a battery. However Bell reasoned that by adding a telephone receiver to the same circuit he would be able to hear what Sabine could only see.[17]

As Bell's former associate, Thomas Watson, was fully occupied as the superintendent of manufacturing for the nascent Bell Telephone Company back in Boston, Massachusetts, Bell hired Charles Sumner Tainter, an instrument maker who had previously been assigned to the U.S. 1874 Transit of Venus Commission, for his new 'L' Street laboratory in Washington, at the rate of $15 per week.[18]

On February 19, 1880, the pair had managed to make a functional photophone in their new laboratory by attaching a set of metallic gratings to a diaphragm, with a beam of light being interrupted by the gratings movement in response to spoken sounds. When the modulated light beam fell upon their selenium receiver Bell, on his headphones, was able to clearly hear Tainter singing Auld Lang Syne.[19]

In an April 1, 1880, Washington, D.C., experiment, Bell and Tainter communicated some 79 metres (259 ft) along an alleyway to the laboratory's rear window. Then a few months later on June 21 they succeeded in communicating clearly over a distance of some 213 meters (about 700 ft.), using plain sunlight as their light source, practical electrical lighting having only just been introduced to the U.S. by Edison. The transmitter in their latter experiments had sunlight reflected off the surface of a very thin mirror positioned at the end of a speaking tube; as words were spoken they cause the mirror to oscillate between convex and concave, altering the amount of light reflected from its surface to the receiver. Tainter, who was on the roof of the Franklin School, spoke to Bell, who was in his laboratory listening and who signaled back to Tainter by waving his hat vigorously from the window, as had been requested.[6]

The receiver was a parabolic mirror with selenium cells at its focal point.[5] Conducted from the roof of the Franklin School to Bell's laboratory at 1325 'L' Street, this was the world's first formal wireless telephone communication (away from their laboratory), thus making the photophone the world's earliest known voice wireless telephone system,[citation needed] at least 19 years ahead of the first spoken radio wave transmissions. Before Bell and Tainter had concluded their research in order to move on to the development of the Graphophone, they had devised some 50 different methods of modulating and demodulating light beams for optical telephony.[20]

Reception and adoption

[edit]The telephone itself was still something of a novelty, and radio was decades away from commercialization. The social resistance to the photophone's futuristic form of communications could be seen in an August 1880 New York Times commentary:[21][22]

The ordinary man ... will find a little difficulty in comprehending how sunbeams are to be used. Does Prof. Bell intend to connect Boston and Cambridge ... with a line of sunbeams hung on telegraph posts, and, if so, what diameter are the sunbeams to be ....[and] will it be necessary to insulate them against the weather ... until (the public) sees a man going through the streets with a coil of No. 12 sunbeams on his shoulder, and suspending them from pole to pole, there will be a general feeling that there is something about Professor Bell's photophone which places a tremendous strain on human credulity.

However at the time of their February 1880 breakthrough, Bell was immensely proud of the achievement, to the point that he wanted to name his new second daughter "Photophone", which was subtly discouraged by his wife Mabel Bell (they instead chose "Marian", with "Daisy" as her nickname).[23] He wrote somewhat enthusiastically:[4][24]

I have heard articulate speech by sunlight! I have heard a ray of the sun laugh and cough and sing! ...I have been able to hear a shadow and I have even perceived by ear the passage of a cloud across the sun's disk. You are the grandfather of the Photophone and I want to share my delight at my success.

— Alexander Graham Bell, in a letter to his father Alexander Melville Bell, dated February 26, 1880

Bell transferred the photophone's intellectual property rights to the American Bell Telephone Company in May 1880.[25] While Bell had hoped his new photophone could be used by ships at sea and to also displace the plethora of telephone lines that were blooming along busy city boulevards,[26] his design failed to protect its transmissions from outdoor interferences such as clouds, fog, rain, snow and such, that could easily disrupt the transmission of light.[27] Factors such as the weather and the lack of light inhibited the use of Bell's invention.[28] Not long after its invention laboratories within the Bell System continued to improve the photophone in the hope that it could supplement or replace expensive conventional telephone lines. Its earliest non-experimental use came with military communication systems during World War I and II, its key advantage being that its light-based transmissions could not be intercepted by the enemy.

Bell pondered the photophone's possible scientific use in the spectral analysis of artificial light sources, stars and sunspots. He later also speculated on its possible future applications, though he did not anticipate either the laser or fiber-optic telecommunications:[24]

Can Imagination picture what the future of this invention is to be!.... We may talk by light to any visible distance without any conduction wire.... In general science, discoveries will be make by the Photophone that are undreamed of just now.

Further development

[edit]

Although Bell Telephone researchers made several modest incremental improvements on Bell and Tainter's design, Marconi's radio transmissions started to far surpass the maximum range of the photophone as early as 1897[8] and further development of the photophone was largely arrested until German-Austrian experiments began at the turn of the 20th century.

The German physicist Ernst Ruhmer believed that the increased sensitivity of his improved selenium cells, combined with the superior receiving capabilities of professor H. T. Simon's "speaking arc", would make the photophone practical over longer signalling distances. Ruhmer carried out a series of experimental transmissions along the Havel river and on Lake Wannsee from 1901 to 1902. He reported achieving sending distances under good conditions of 15 kilometers (9 miles),[30] with equal success during the day and at night. He continued his experiments around Berlin through 1904, in conjunction with the German Navy, which supplied high-powered searchlights for use in the transmissions.[31]

The German Siemens & Halske Company boosted the photophone's range by utilizing current-modulated carbon arc lamps which provided a useful range of approximately 8 kilometres (5.0 mi). They produced units commercially for the German Navy, which were further adapted to increase their range to 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) using voice-modulated ship searchlights.[5]

British Admiralty research during WWI resulted in the development of a vibrating mirror modulator in 1916. More sensitive molybdenite receiver cells, which also had greater sensitivity to infrared radiation, replaced the older selenium cells in 1917.[5] The United States and German governments also worked on technical improvements to Bell's system.[32]

By 1935 the German Carl Zeiss Company had started producing infrared photophones for the German Army's tank battalions, employing tungsten lamps with infrared filters which were modulated by vibrating mirrors or prisms. These also used receivers which employed lead sulfide detector cells and amplifiers, boosting their range to 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) under optimal conditions. The Japanese and Italian armies also attempted similar development of lightwave telecommunications before 1945.[5]

Several military laboratories, including those in the United States, continued R&D efforts on the photophone into the 1950s, experimenting with high-pressure vapour and mercury arc lamps of between 500 and 2,000 watts power.[5]

Commemorations

[edit]FROM THE TOP FLOOR OF THIS BUILDING

WAS SENT ON JUNE 3, 1880

OVER A BEAM OF LIGHT TO 1325 'L' STREET

THE FIRST WIRELESS TELEPHONE MESSAGE

IN THE HISTORY OF THE WORLD.

THE APPARATUS USED IN SENDING THE MESSAGE

WAS THE PHOTOPHONE INVENTED BY

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL

INVENTOR OF THE TELEPHONE

THIS PLAQUE WAS PLACED HERE BY

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL CHAPTER

TELEPHONE PIONEERS OF AMERICA

MARCH 3, 1947

THE CENTENNIAL OF DR. BELL'S BIRTH

On March 3, 1947, the centenary of Alexander Graham Bell's birth, the Telephone Pioneers of America dedicated a historical marker on the side of one of the buildings, the Franklin School, which Bell and Sumner Tainter used for their first formal trial involving a considerable distance. Tainter had originally stood on the roof of the school building and transmitted to Bell at the window of his laboratory. The marker did not acknowledge Tainter's scientific and engineering contributions.[original research?]

On February 19, 1980, exactly 100 years to the day after Bell and Tainter's first photophone transmission in their laboratory, staff from the Smithsonian Institution, the National Geographic Society and AT&T's Bell Labs gathered at the location of Bell's former 1325 'L' Street Volta Laboratory in Washington, D.C. for a commemoration of the event.[11][33]

The Photophone Centenary commemoration had first been proposed by electronics researcher and writer Forrest M. Mims, who suggested it to Dr. Melville Bell Grosvenor, the inventor's grandson, during a visit to his office at the National Geographic Society. The historic grouping later observed the centennial of the photophone's first successful laboratory transmission by using Mims hand-made demonstration photophone, which functioned similar to Bell and Tainter's model.[20][Note 1]

Mims also built and provided a pair of modern hand-held battery-powered LED transceivers connected by 100 yards (91 m) of optical fiber. The Bell Labs' Richard Gundlach and the Smithsonian's Elliot Sivowitch used the device at the commemoration to demonstrate one of the photophone's modern-day descendants. The National Geographic Society also mounted a special educational exhibit in its Explorer's Hall, highlighting the photophone's invention with original items borrowed from the Smithsonian Institution.[34]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Footnotes

- ^ The demonstration model was a replica in principle but not identical to Bell and Tainter's model. The commemorative model transmitter was a thin mirror cemented to a short aluminum speaking tube, and its receiver was a silicon solar cell and audio amplifier, both installed in a lantern light housing.

Citations

- ^ Bruce 1990, pg. 336

- ^ Jones, Newell. First 'Radio' Built by San Diego Resident Partner of Inventor of Telephone: Keeps Notebook of Experiences With Bell Archived 2002-02-19 at the Wayback Machine, San Diego Evening Tribune, July 31, 1937. Retrieved from the University of San Diego History Department website, November 26, 2009.

- ^ Bruce 1990, pg. 338

- ^ a b Carson 2007, pg. 76–78

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Groth, Mike. Photophones Revisted, 'Amateur Radio' magazine, Wireless Institute of Australia, Melbourne, April 1987 pp. 12–17 and May 1987 pp. 13–17.

- ^ a b Mims 1982, p. 11.

- ^ Phillipson, Donald J.C., and Neilson, Laura Bell, Alexander Graham, The Canadian Encyclopedia online. Retrieved 2009-08-06

- ^ a b Mims 1982, p. 14.

- ^ Morgan, Tim J. "The Fiber Optic Backbone", University of North Texas, 2011.

- ^ Miller, Stewart E. "Lightwaves and Telecommunication", American Scientist, Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society, January–February 1984, Vol. 72, No. 1, pp. 66–71, Issue Stable URL.

- ^ a b Gallardo, Arturo; Mims III, Forrest M. Fiber-optic Communication Began 130 Years Ago, San Antonio Express-News, June 21, 2010. Accessed January 1, 2013.

- ^ Clark, J. An Introduction to Communications with Optical Carriers, IEEE Students' Quarterly Journal, June 1966, Vol.36, Iss.144, pp. 218–222, ISSN 0039-2871, doi:10.1049/sqj.1966.0040. Retrieved from IEEExplore website August 19, 2011.

- ^ Bell, Alexander Graham (28 May 1881). "The Production of Sound by Radiant Energy". Science. 2 (48): 242–253. doi:10.1126/science.os-2.49.242. JSTOR 2900190. PMID 17741736. Retrieved 11 Oct 2022.

- ^ Bell, Alexander Graham. "On the Production and Reproduction of Speech by Light", American Journal of Science, October 1880, Vol. 20, No. 118, pp. 305–324.

- ^ Grosvenor and Wesson 1997, p. 104.

- ^ Ernest Victor Heyn, Fire of genius: inventors of the past century: based on the files of Popular Science Monthly since its founding in 1872, Anchor Press/Doubleday – 1976, page 74

- ^ Mims 1982, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Mims 1982, p. 7.

- ^ Mims 1982, p. 10.

- ^ a b Mims 1982, p. 12.

- ^ Editorial, The New York Times, August 30, 1880

- ^ International Fiber Optics & Communication, June 1986, p. 29

- ^ Carson 2007, pg.77

- ^ a b Bruce 1990, pg. 337

- ^ Bruce 1990, pg. 339

- ^ Hecht, Jeff. Fiber Optics Calls Up The Past, New Scientist, January 12, 1984, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Carson 2007, pp. 77–78

- ^ Carson 2007, pg.78

- ^ Cover page Technical World, March 1905.

- ^ "Correspondence: Wireless Telephony" (October 30, 1902 letter from Ernst Ruhmer), The Electrician, November 7, 1902, page 111.

- ^ Wireless Telephony In Theory and Practice by Ernst Ruhmer, 1908, pages 55–59.

- ^ Mims 1982, pp. 14–17.

- ^ Hecht, Jeff. "Yarns From The Technological Jungle: Siliconnections: Coming Of Age In The Electronic Era", New Scientist, February 27, 1986, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Mims 1982, pp. 6 & 12.

Bibliography

- Carson, Mary Kay (2007). "chapter 8". Alexander Graham Bell: Giving Voice To The World. Sterling Biographies. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. pp. 76–78. ISBN 978-1-4027-3230-0. OCLC 182527281.

- Bell, A. G: "On the Production and Reproduction of Sound by Light", American Journal of Science, Third Series, Vol. XX, #118, October 1880, pp. 305–324; also published as "Selenium and the Photophone" in Nature, September 1880.

- Bruce, Robert V Bell: Alexander Bell and the Conquest of Solitude, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-8014-9691-8.

- Mims III, Forest M. The First Century of Lightwave Communications, Fiber Optics Weekly Update, Information Gatekeepers, February 10–26, 1982, pp. 6–23.

- Grosvenor, Edwin S. and Morgan Wesson. Alexander Graham Bell: The Life and Times of the Man Who Invented the Telephone. New York: Harry N. Abrahms, Inc., 1997. ISBN 0-8109-4005-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Chris Long and Mike Groth's optical audio telecommunications webpage

- Ackroyd, William. "The Photophone" in "Science for All", Vol. 2 (R. Brown, ed.), Cassell & Co., London, circa 1884, pp. 307–312. A popular account, profusely illustrated with steel engravings.

- Armengaud, J. " Le photophone de M.Graham Bell". Soc. Ing. civ. Mem., year 1880, Vol 2. pp. 513–522.

- AT&T Company. "The Radiophone", pamphlet distributed at Louisiana Purchase Exhibition, St Louis, Missouri, 1904. Describes the photophone work of Hammond V Hayes at the Bell Labs (patented 1897) and the German engineer H T Simon in the same year.

- Bell, Alexander Graham. "On the Production and Reproduction of Sound by Light: the Photophone". Am. Ass. for the Advancement of Sci., Proc., Vol 29., October 1880, pp. 115–136. Also in American Journal of Science, Series 3. No. 20, 1880, pp. 305–324; Eng. L., 30. 1880, pp. 240–242; Electrician, Vol 5. 1880, pp. 214–215, 220–221, 237; Journal of the Society of Telegraph Engineers, No. 9, 1880, pp. 404–426; Nat. L., Vol 22. 1880, pp. 500–503; Ann. Chim. Phys., Serie 5. Vol 21. 1880, pp. 399–430; E.T.Z., Vol. 1. 1880, pp. 391–396. Discussed at length in Eng. L., Vol 30. 1880, pp. 253–254, 407–409. In these papers, Bell accords the credit for the first demonstrations of the transmission of speech by light to a Mr A C Brown of London "in September or October 1878".

- Bell, Alexander Graham. "Sur l'application du photophone a l'etude des bruits qui ont lieu a la surface solaire". C. R., Vol. 91. 1880, pp. 726–727.

- Bell, Alexander Graham. "Professor A G Bell on Selenium and the Photophone". Pharm. J. and Trans., Series 3. Vol. 11., 1880–1881, pp. 272–276; The Electrician No 5, 18 September 1880, pp 220–221 and 2 October 1880 pp 237; Nature (London) Vol 22, 23 September 1880, pp. 500–503; Engineering Vol 30, pp 240–242, 253, 254, 407–409; and Journal of the Society of Telegraph Engineers Vol 9, pp 375–387.

- Bell, Alexander Graham. "Other papers on the photophone" E.T.Z. No. 1, 1880, pp 391–396; Journal of the Society for the Arts 1880, No. 28, pp 847–848 & No. 29 pp 60–62; C.R. No. 91, 1880–1881, pp 595–598, 726, 727, 929–931, 982, 1882 pp 409–412, 450, 451, 1224–1227.

- Bell, Alexander Graham. "Le Photophone De La Production Et De La Lumiere". Gauthier-Villars, Imprimeur-Libraire, Paris. 1880. (Note: this is item #26, Folder #4, as noted in "Finding Aid for the Alexander Graham Bell Collection, 1880–1925", Collection number: 308, UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division, as viewable at the Online Archive of California)

- "Bell's Photophone". Nature Vol 24, 4 November 1880; The Electrician, Vol. 6, 1881, pp. 136–138.

- Appleton's Journal. "The Photophone". Appleton's Journal, Vol. 10 No. 56, New York, February 1881, pp. 181–182.

- Bidwell, Shelford. "The Photophone". Nature., 23. 1881, pp. 58–59.

- Bidwell, Shelford. "Selenium and Its Applications to the Photophone and Telephotography". Proceedings of the Royal Institution (G.B.), Vol 9. 1881, pp. 524–535; The English Mechanic and World Of Science, Vol. 33, 22 April 1881, pp. 158–159 and 29 April 1881 pp. 180–181. Also in Chem. News, Vol. 44, 1881, pp. 1–3, 18–21. (From a lecture at the Royal Institution on 11 March 1881).

- Breguet, A. "Les recepteurs photophoniques de selenium". Ann. Chim. Phys., Series 5. Vol 21. 1880, pp. 560–563.

- Breguet, A. "Sur les experiences photophonique du Professeur Alexander Graham Bell et de M. Sumner Tainter": C.R.; Vol 91., 1880, pp 595–598.

- Electrician. "Bell's Photophone", Electrician, Vol. 6, February 5, 1881, pp. 136–138,183.

- Jamieson, Andrew. Nat. L., Vol. 10, 1881, p. 11. This Glasgow scientist seems to have been the first to suggest the usage of a manometric gas flame for optical transmission, demonstrated at a meeting of the Glasgow Philosophical Society; "The History of selenium and its action in the Bell Photophone, with description of recently designed form", Proceedings of the Philosophical Society of Glasgow No. 13, 1881, ***Moser, J. "The Microphonic Action of Selenium Cells". Phys. Soc., Proc., Vol. 4, 1881, pp. 348–360. Also in Phil. Mag., Series 5, Vol.12, 1881, pp. 212–223.

- Kalischer, S. "Photophon Ohne Batterie". Rep. f. Phys., Vol. 17., 1881, pp. 563–570.

- MacKenzie, Catherine "Alexander Graham Bell", Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, p. 226, 1928.

- Mercadier, E. "La radiophonie indirecte". Lumiere Electrique, Vol. 4, 1881, pp. 295–299.

- Mercadier, E. "Sur la radiophonie produite a l'aide du selenium". C. R., Vol. 92,1881, pp. 705–707.

- Mercadier, E. "Sur la construction de recepteurs photophoniques a selenium". C. R., Vol. 92, 1881, pp. 789–790.

- Mercadier, E. "Sur l'influence de la temperature sur les recepteurs radiophoniques a selenium". C. R., Vol. 92, 1881, pp. 1407–1408.

- Molera & Cebrian. "The Photophone". Eng. L., Vol. 31, 1881, p. 358.

- Preece, Sir William H. "Radiophony", Engineering Vol. 32, 8 July 1881, pp. 29–33; Journal of the Society of Telegraph Engineers, Vol 10, 1881, pp. 212–228. On the photophone.

- Rankine, A.O. "Talking over a Sunbeam". El. Exp. (N. Y.), Vol. 7, 1920, pp. 1265–1316.

- Sternberg, J.M. The Volta Prize of the French Academy Awarded to Prof. Alexander Graham Bell: A Talk With Dr. J.M. Sternberg, The Evening Traveler, September 1, 1880, The Alexander Graham Bell Papers at the Library of Congress

- Thompson, Silvanus P. "Notes on the Construction of the Photophone". Phys. Soc.Proc., Vol. 4, 1881, pp. 184–190. Also in Phil. Mag., Vol. 11, 1881, pp. 286–291. Abstracted in Chem. News, Vol. 43, 1881, p. 43; Eng. L., Vol. 31, 1881, p. 96.

- Tomlinson, H. "The Photophone". Nat. L., Vol. 23, 1881, pp. 457–458.

- U.S. Radio and Television Corp. "Ultra-violet rays used in Television", New York Times, 29 May 1929, p. 5: Demonstration of transmission of a low definition (mechanically scanned) video signal over a modulated light beam. Terminal stations 50 feet apart. Public demonstration at Bamberger and Company's Store, Newark, New Jersey. Earliest known usage of modulated light comms for conveying video signals. See also report "Invisible Ray Transmits Pictures" in Science and Invention, November 1929, Vol. 17, p. 629.

- White, R.H. "Photophone". Harmsworth's Wireless Encyclopaedia, Vol. 3, pp. 1541–1544.

- Weinhold, A. "Herstellung von Selenwiderstanden fur Photophonzwecke". E.T.Z., Vol. 1, 1880, p. 423.

External links

[edit]- Bell's speech before the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Boston on August 27, 1880, in which he presented his paper "On the Production and Reproduction of Sound by Light: the Photophone".

- Long-distance Atmospheric Optical Communications, by Chris Long and Mike Groth (VK7MJ)

- Téléphone et photophone: les contributions indirectes de Graham Bell à l'idée de la vision à distance par l'électricité (1880–1895 (in French)

Photophone

View on GrokipediaInvention and History

Development by Bell and Tainter

Following the success of the telephone, Alexander Graham Bell sought to achieve wireless transmission of sound using light as the carrier medium, motivated by the potential for greater freedom from physical wires. This pursuit was inspired by the 1873 discovery of selenium's photoconductivity by Willoughby Smith, an English electrical engineer testing the material for submarine telegraph cables, who observed that its electrical resistance decreased under exposure to light.[6] Bell envisioned modulating a light beam with sound vibrations to convey speech optically, extending his earlier work on acoustic transmission.[7] In late 1879, Bell began collaborating with Charles Sumner Tainter, a skilled instrument maker and mechanic, at the newly established Volta Laboratory in Washington, D.C., funded by Bell's 1880 Volta Prize award for the telephone. Tainter's expertise in precision instrumentation complemented Bell's theoretical insights, enabling rapid prototyping of experimental devices. Their joint efforts focused on integrating selenium receivers with light sources to detect modulated signals, marking a shift from wired telephony to optical methods. The partnership formalized the photophone's development, with Tainter handling much of the mechanical design.[2] Key milestones included the initial conceptualization in 1879, followed by the first laboratory success on February 19, 1880, when they transmitted intelligible voice over a short indoor distance using a sunlight-modulated beam and selenium detector. This breakthrough confirmed the feasibility of optical sound transmission, prompting further refinements. The master patent, listing Bell as inventor but reflecting Tainter's contributions, was filed in August 1880 and issued as U.S. Patent 235,199 on December 7, 1880, to the American Bell Telephone Company.[1] Bell personally regarded the photophone as his greatest achievement, surpassing even the telephone in conceptual importance, as he expressed in his 1880 paper "On the Production and Reproduction of Sound by Light," presented to the American Association for the Advancement of Science. In this work, he detailed the device's principles and experiments, emphasizing its potential to revolutionize communication through radiant energy. Later reflections, including interviews near the end of his life, reinforced this view, highlighting the photophone's foundational role in wireless technology.[7]First Demonstrations

The initial successful test of the photophone occurred indoors on February 19, 1880, at Alexander Graham Bell's Volta Laboratory on L Street in Washington, D.C., where Bell and his assistant Charles Sumner Tainter achieved short-range voice transmission using a beam of sunlight.[8] In this proof-of-concept experiment, the apparatus was divided between two floors of the lab, with Tainter singing "Auld Lang Syne" and speaking "Hoy, hoy" into the transmitter on one floor, while Bell clearly heard the sounds reproduced through telephone receivers connected to the selenium-based receiver on the other floor.[8] The setup employed a focused beam of sunlight modulated by a vibrating mirror attached to the transmitter's diaphragm, demonstrating the device's ability to carry audible speech over light without wires.[9] A subsequent outdoor test took place on April 1, 1880, when Bell and Tainter successfully transmitted voice over 79 meters (259 feet) along an alleyway to the rear window of the laboratory. This experiment, using a similar sunlight-modulated setup, marked the first outdoor validation of the photophone and extended its range beyond the indoor confines.[3] An outdoor public demonstration followed on June 21, 1880, marking the photophone's first long-distance validation, with transmission from the roof of the Franklin School at 925 13th Street NW to Bell's laboratory window at 1325 L Street NW, a distance of 213 meters (approximately 700 feet).[3] Tainter, positioned on the school roof, spoke into the transmitter, sending the message "Mr. Bell—if you understand what I say come to the window and wave your hat," which Bell received clearly at the lab and acknowledged by waving his hat as instructed.[8] The transmitter featured a speaking trumpet-like mouthpiece with a thin mica diaphragm that vibrated with the voice, modulating a focused sunlight beam passed through a lens onto the diaphragm's attached mirror, while the receiver used a selenium cell to convert the modulated light back into sound.[9] This public unveiling was attended by several dignitaries and officials, including the Superintendent of the U.S. Patent Office, underscoring the event's significance as the world's first formal demonstration of wireless voice transmission over a substantial distance.[8] The demonstrations were meticulously recorded in Bell's laboratory journals and corroborated by contemporary scientific reports, providing primary documentation of the photophone's early viability.[10]Design and Operation

Core Principles

The photophone operated on the principle of amplitude modulation of a light beam by acoustic signals, where sound waves from a human voice caused mechanical vibrations in a flexible reflector, such as a thin silvered glass or mica diaphragm, altering the angle of reflection for an incident light source like sunlight.[9] These vibrations imparted an undulatory motion to the reflector, causing the reflected beam to vary in intensity at the receiver by changing the direction and concentration of the light rays, thereby encoding the audio signal optically without electrical transmission in the optical path.[11] This mechanical modulation relied on the direct coupling of sound pressure to the reflector's surface tension, producing variations in beam intensity proportional to the amplitude and frequency of the voice.[1] At the receiver, the varying light intensity was converted back to an electrical signal through the photoconductive properties of selenium, a material whose electrical resistance decreases significantly under illumination—dropping to as little as one-fifteenth of its value in darkness.[11] The selenium cell, placed at the focus of a parabolic mirror to capture the modulated beam, formed part of a simple circuit with a battery and a telephone receiver; as light intensity fluctuated, the cell's resistance changed inversely, modulating the current flow and reproducing the original sound acoustically via the telephone diaphragm.[12] This photoconductive effect, first noted in selenium's response to radiant energy, enabled the optical-to-electrical transduction essential to the device's function.[13] The intensity variation in the light beam followed the basic optical relation for reflection, where the received intensity is proportional to , with representing the angle of incidence modulated by the sound-induced tilt of the reflector; for small angular displacements, this cosine dependence ensured that intensity fluctuations mirrored the acoustic waveform qualitatively.[1] Overall, the photophone's operation was entirely non-electronic, depending solely on mechanical vibration for modulation and photochemical resistance changes for detection, predating vacuum tubes and active electronics by decades.[14]Key Components

The transmitter in the original 1880 photophone, developed by Alexander Graham Bell and Charles Sumner Tainter, featured a speaking trumpet connected to a thin, flexible diaphragm typically made of silvered mica or glass, which vibrated in response to acoustic waves from the speaker's voice.[11][9] This diaphragm served as a reflecting surface, with sunlight or another light source focused onto it via a lens, causing the reflected beam to undulate in intensity proportional to the diaphragm's movements.[11] The assembly was mounted in an adjustable frame with pivots for aligning the beam, often incorporating additional lenses or a parabolic mirror to collimate the modulated light into a directed pencil of rays.[9] The light beam traveled along a straight, line-of-sight path between the transmitter and receiver, requiring unobstructed visibility and capable of extending up to several hundred meters depending on conditions.[11] No waveguides or intermediaries were used; the beam remained free-space propagated, with its modulation preserving the audio signal's variations.[2] At the receiver, a parabolic reflector captured and concentrated the incoming beam onto a selenium-based photodetector, usually a cell formed by layering selenium between insulating disks like mica and conductive plates such as platinum or brass, sensitized through heat treatment to enhance photoconductivity.[11][12] Electrodes from the selenium cell connected to a simple circuit including a battery for power and a telephone receiver to convert the varying electrical current—induced by fluctuations in the cell's resistance—back into audible sound.[11][2] The photophone's power derived primarily from natural sunlight as the illumination source for the transmitter, supplemented optionally by artificial lamps such as oxyhydrogen or kerosene for indoor or low-light use, while the receiver's circuit drew from a standard battery; the entire system operated without active electronics or amplification.[11]Reception and Early Adoption

Public and Scientific Response

The initial public response to the photophone's demonstrations in 1880 was marked by a mix of awe and caution, as reported in contemporary media. An August 30, 1880, article in The New York Times expressed skepticism about its practicality, questioning whether Prof. Bell intended to connect cities "with a line of sunbeams hung on telegraph posts" and stating that there was "something about Professor Bell’s photophone which places a tremendous strain on human credulity."[15] Despite highlighting its potential for wireless speech transmission over distances up to 200 meters, the piece doubted its viability beyond a scientific curiosity. Scientific interest was immediate and enthusiastic following Alexander Graham Bell's presentation of the photophone at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) meeting in Boston on August 27, 1880. In his paper "The Photophone," Bell detailed the device's operation, demonstrating how modulated light beams could carry articulate speech, which sparked lively discussions on the possibilities of optical telegraphy.[16] The AAAS presentation lent significant credibility to the invention, positioning it as a noteworthy advancement in acoustics and optics among leading researchers of the era. The photophone's patent, U.S. No. 235,199 for "Apparatus for Signalling and Communicating, Called Photophone," was granted to Bell on December 7, 1880, shortly after his application on August 28.[1] It was regarded as a natural extension of Bell's pioneering work on the telephone, building on principles of sound transmission but innovating with light as the medium, though it saw no immediate commercialization due to challenges in reliable outdoor transmission.[2] Bell actively promoted the photophone's revolutionary potential in a detailed 1880 paper published in the American Journal of Science (Silliman's Journal), titled "On the Production and Reproduction of Sound by Light." There, he characterized it as enabling "aerial telephony," a wireless system free from wires that could transform long-distance communication by harnessing sunlight's radiant energy, emphasizing its superiority over conductive methods for certain applications.Limitations and Challenges

The photophone's transmission relied on a direct line-of-sight beam of light, rendering it highly susceptible to atmospheric conditions such as fog, rain, mist, smoke, or dust, which caused significant signal attenuation—up to 200 dB/km in thick fog—thereby restricting reliable operation to clear weather and limiting demonstrated ranges to approximately 213 meters using sunlight.[17] Clouds or precipitation could completely disrupt the modulated light beam, confining the device's practical use to short distances under ideal daytime conditions without obstacles.[2] Signal quality further deteriorated with distance due to inherent attenuation of the light beam, compounded by interference from ambient light sources that introduced noise into the selenium receiver and required precise alignment to maintain focus, often leading to misalignment issues in non-laboratory settings.[17] The receiver's crystalline selenium cells, while sensitive to light variations, exhibited slow photoconductivity response times with noticeable lags, distorting audio signals and preventing faithful reproduction of speech, particularly for higher frequencies.[18] Additionally, the absence of electronic amplification technologies in the era exacerbated weak signals, as the photophone lacked means to boost the modest electrical output from the selenium cells before conversion to sound.[17] Economically, the photophone offered no immediate commercial viability compared to the emerging wired telephone networks, which provided consistent, weather-independent connections over longer distances with simpler infrastructure.[19] Its requirement for meticulous line-of-sight alignment between transmitter and receiver, often involving large parabolic reflectors, posed high setup complexity and maintenance costs, deterring practical deployment in urban or varied terrains during the late 19th century.[17]Later Developments

Improvements in the 20th Century

In the early 1900s, German physicist Ernst Ruhmer advanced photophone technology with his selenium-based optophone, introduced in 1901, which addressed range limitations by employing high-intensity arc lights to modulate signals onto a light beam. This design utilized improved selenium cells as receivers, whose resistance varied with light intensity to demodulate the signal, enabling reliable voice transmission over distances up to 15 km under favorable conditions. Ruhmer's work, detailed in his 1908 book Wireless Telephony in Theory and Practice, marked a key step in making optical telephony practical for longer spans despite persistent issues like weather sensitivity.[20][21] During the 1920s, electronic enhancements further refined photophone systems, incorporating vacuum tube amplifiers to boost weak received signals and shifting to infrared wavelengths for covert operation and reduced visibility. Theodore Case's development of infrared telegraphy and telephony at his research laboratory utilized thallium sulfide (Thalofide) cells sensitive to near-infrared light, combined with electronic amplification to extend usability in low-light or obscured environments. These innovations, building on pre-war experiments, laid groundwork for military applications by improving signal fidelity and security.[22][23] World War II saw significant military adoption of infrared photophones by the U.S. Army Signal Corps for secure, line-of-sight communication, where modulated infrared beams allowed voice and code transmission without radio interception risks. Devices employed lead sulfide detectors and vacuum tube amplifiers, achieving voice ranges of approximately 8 km in clear weather conditions, with longer distances possible for Morse code signaling using carbon arc sources and narrow-beam projectors. These systems, surveyed in post-war analyses, proved vital for tactical coordination in theaters like the Pacific, though fog and smoke remained challenges.[24] Post-WWII developments in the 1960s shifted toward laser-based prototypes, dramatically enhancing modulation speeds and transmission distances through coherent light beams. In 1963, researchers at Bell Laboratories demonstrated voice communication over a helium-neon laser modulated via an acousto-optic device, transmitting clear audio across several kilometers with bandwidths far exceeding earlier analog systems. This experiment highlighted lasers' potential for high-fidelity optical links, paving the way for future free-space systems while overcoming modulation limitations of incandescent sources.[25]Influence on Modern Technology

The photophone, invented by Alexander Graham Bell in 1880, served as an early precursor to modern fiber-optic communication systems by demonstrating the transmission of audio signals via modulated light beams, a principle that underpins the use of light for data conveyance in optical fibers.[26] These systems now form the backbone of global telecommunications, with fiber optics carrying over 99% of international internet data traffic through undersea cables that employ techniques like wavelength-division multiplexing to achieve high-capacity transmission.[27] Bell's concept of modulating light intensity to encode information directly influenced the development of guided optical pathways, enabling the scalable, high-speed networks essential for contemporary digital infrastructure.[28] In free-space optical (FSO) communication, the photophone's wireless light-based transmission has evolved into laser-driven systems that avoid physical media, providing high-bandwidth links in environments where cables are impractical. For instance, NASA's Lunar Laser Communication Demonstration in 2013 successfully transmitted data at rates up to 622 Mbps from the Moon to Earth using pulsed laser beams, echoing Bell's original vision of line-of-sight optical signaling but with vastly improved reliability and distance.[29] In 2025, General Dynamics Mission Systems deployed PhantomLink FSO systems achieving data rates up to 10 Gbps for secure communications, while the Telecommunications Industry Association (TIA) initiated standards development for FSOC to extend fiber networks. Urban applications, such as Li-Fi technology, further extend this legacy by utilizing visible light communication (VLC) from LED sources to deliver wireless data at speeds exceeding gigabits per second, offering interference-free alternatives to radio-frequency systems in dense settings like offices or vehicles.[30][31][32] Recent advancements in the 2020s have revived photophone-inspired concepts in quantum-secure optical links, where light modulation ensures tamper-evident data transfer over fiber or free space. Researchers have integrated quantum key distribution with high-capacity optical systems to achieve terabit-per-second rates while providing unbreakable encryption based on quantum principles, addressing vulnerabilities in classical networks.[33] In IoT applications, VLC systems draw on these early ideas to enable secure, low-latency connectivity for devices, with prototypes demonstrating reliable data exchange in indoor environments using everyday lighting fixtures.[34] Overall, optical technologies rooted in the photophone's foundational principles now support the majority of global telecommunications volume, facilitating everything from cloud computing to real-time sensing in smart ecosystems.[35]Legacy

Commemorations

In 1947, marking the centennial of Alexander Graham Bell's birth, the Alexander Graham Bell Chapter of the Telephone Pioneers of America installed a historical plaque at the Franklin School in Washington, D.C., to commemorate the site's role in the first wireless telephone transmission via photophone on June 3, 1880.[36] The plaque highlights the photophone as Bell's invention for sending voice over a beam of light from the school's rooftop to a laboratory two blocks away.[37] On February 19, 1980, exactly 100 years after Bell and Charles Sumner Tainter's initial laboratory success with the photophone, the Smithsonian Institution and Bell Laboratories organized a centennial event featuring live demonstrations using a replica of the device.[3] Participants recreated the transmission of voice over light, underscoring the photophone's pioneering role in optical communication.[38] The photophone has been recognized in various tributes to Bell's inventive legacy, including its prominent inclusion in biographical accounts that emphasize its significance alongside the telephone.[39] For instance, Bell himself regarded the photophone as his most important invention, a view echoed in historical narratives of his work on wireless sound transmission.[2]Significance in Communication History

The photophone stands as a landmark in the history of wireless communication, marking the first successful transmission of articulated human speech using a modulated beam of light rather than electrical conduction or radio waves. Invented by Alexander Graham Bell and Charles Sumner Tainter in 1880 at the Volta Laboratory in Washington, D.C., the device operated by converting sound vibrations into variations in light intensity, which were then demodulated at the receiver using a selenium cell. This achievement preceded Heinrich Hertz's 1887 experiments with electromagnetic radio waves by seven years, positioning the photophone as the inaugural demonstration of non-radio electromagnetic voice transmission and expanding the conceptual boundaries of signaling beyond wired telephony.[40][41][42] Bell viewed the photophone as "the greatest invention I have ever made; greater than the telephone," reflecting its profound implications for harnessing light as a carrier of information. Developed amid Bell's broader explorations at the Volta Laboratory—funded by the Volta Prize for the telephone—the device exemplified his shift from purely acoustic innovations to interdisciplinary work integrating sound, optics, and electricity. This bridged 19th-century acoustic technologies, rooted in mechanical vibration and conduction, with the electronic and photonic paradigms that propelled 20th-century advancements, while underscoring Bell's versatility as an inventor whose laboratory pursuits also advanced sound recording techniques and informed his dedicated efforts in audiology and deaf education.[40][14][43] On a broader scale, the photophone anticipated the utilization of the electromagnetic spectrum across diverse wavelengths for communication, from visible light to microwaves, by proving the viability of optical modulation for voice signals over distances exceeding 200 meters. Its foundational principles of light-based information transfer have been recognized in historical overviews of visible light communication, influencing the development of international standards for optical frequency bands by organizations such as the International Telecommunication Union. In this way, the photophone not only expanded early understandings of wireless potential but also contributed to the evolutionary framework for spectrum allocation and photonic signaling in global communication protocols.[44][41]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Franklin_School_-_Alexander_Graham_Bell_-_plaque_-_Washington_DC.JPG

.jpg/250px-Photophone_plaque_(no_copyright_applies).jpg)

.jpg)