Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Khandoba

View on Wikipedia| Khandoba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sanskrit transliteration | Khaṇḍobā |

| Devanagari | खंडोबा |

| Affiliation | Avatar of Shiva |

| Abode | Jejuri |

| Mantra | Om Shri Martanda Bhairavaya Namah |

| Weapon | Trishula, Sword |

| Mount | Horse |

| Consort | Mhalsa and Banai (chief consorts) |

Khandoba (IAST: Khaṇḍobā), also known as Martanda Bhairava and Malhari, is a Hindu deity worshiped generally as a manifestation of Shiva mainly in the Deccan Plateau of India, especially in the state of Maharashtra and North Karnataka. He is the most popular Kuladevata (family deity) in Maharashtra.[1] He is also the patron deity of some Kshatriya Marathas (warriors), farming castes, shepherd community and Brahmin (priestly) castes as well as several of the hunter/gatherer tribes that are native to the hills and forests of this region.

The sect of Khandoba has linkages with Hindu and Jain traditions, and also assimilates all communities irrespective of caste, including Muslims. The sect of Khandoba as a folk deity dates at least to 12th century. Khandoba emerged as a composite god possessing the attributes of Shiva, Bhairava, Surya and Kartikeya (Skanda). Khandoba is sometimes identified with Mallanna of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh and Mailara of Karnataka.

Khandoba is depicted either in the form of a linga, or as an image of a warrior riding on a horse. The foremost centre of Khandoba worship is the Khandoba temple of Jejuri in Maharashtra. The legends of Khandoba, found in the text Malhari Mahatmya and also narrated in folk songs, revolve around his victory over demons Mani-malla and his marriages.

Etymology and other names

[edit]The name Khandoba comes from the words khadga (sword), the weapon used by Khandoba to kill the demons, and the suffix ba (father). Another name Khanderaya means "king Khandoba". Another variant is Khanderao, where the suffix rao (king) is used. In Sanskrit texts, Khandoba is known as Martanda Bhairava, a combination of Martanda (an epithet of the solar deity Surya) and Shiva's fierce form Bhairava. The name Mallari or Malhari is split as Malla and ari (enemy), thus meaning "enemy of the demon Malla". The Malhari Mahatmya records Martanda Bhairava, pleased with the bravery of Malla, takes the name "Mallari" (the enemy of Malla).[2] Other variants include Malanna (Mallanna) and Mailara (Mailar). Other names include Khandu Gavda, Mhalsa-kant ("husband of Mhalsa") and Jejurica Vani.[3]

Iconography

[edit]

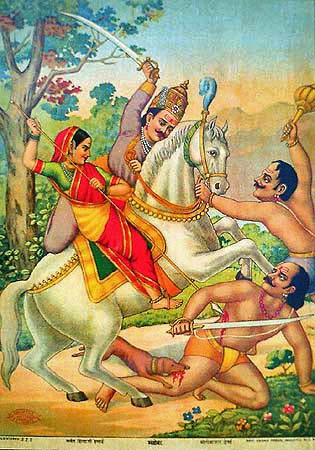

In a popular oleograph representation of Khandoba,[4] Mhalsa is seated in front of Khandoba on his white horse. Mhalsa is piercing a demon's chest with a spear, while a dog is biting his thigh and the horse is hitting his head. The other demon is grabbing the reins of the horse and attacking Khandoba with a club as Khandoba is dismounting the horse and attacking the demon with his sword. In other representations, Khandoba is seen seated on a horse with the heads of demons trod under the horse's hooves or their heads under Khandoba's knees.[5]

In murtis (icons), Khandoba or Mailara is depicted as having four arms, carrying a damaru (drum), trishula (trident), bhandara-patra (turmeric powder-filled bowl) and khadga (sword). Khandoba's images are often dressed as a Maratha sardar,[6] or a Muslim pathan.[7] Often, Khandoba is depicted as a warrior seated on horseback with one or both of his wives and accompanied with one or more dogs.[8] He is also worshipped as the aniconic linga, the symbol of Shiva.[9] Often in Khandoba temples, both representations of Khandoba — the aniconic linga and the anthropomorphic horseback form.[8]

Legends

[edit]Legends of Khandoba generally narrate about the battle between the deity and demons Malla and Mani. The principle written source of the legend is Malhari Mahatmya (Mallari Mahatmya), which claims to be from the chapter Kshetra-kanda of the Sanskrit text Brahmanda Purana, but is not included in standard editions of the Purana.[10] R.C. Dhere and Sontheimer suggests that the Sanskrit Mahatmya was composed around 1460–1510 AD, mostly by a Deshastha Brahmin, to whom Khandoba is the family deity.[11] A version is also available in Marathi by Siddhapal Kesasri (1585).[12] Other sources include the later texts of Jayadri Mahatmya and Martanda Vijaya by Gangadhara (1821)[13] and the oral stories of the Vaghyas, bards of the god.[14]

The legend recounts that the demon Malla and his younger brother Mani, who had gained the boon of invincibility from the god Brahma, create chaos on the earth and torment the sages. When the seven sages approach Shiva for protection, Shiva assumes the form (avatar) of Martanda Bhairava (as the Mahatmya calls Khandoba) on Chaitra Shuddha Poornima at Adimailar, Mailapura near Bidar. He rides the Nandi bull, leading an army of the gods. Martanda Bhairava is described as shining like gold and the Sun, covered in turmeric (Haridra), three-eyed and with a crescent moon on his forehead.[15] The demon army is slaughtered by the gods; finally Khandoba kills Malla and Mani. While dying, Mani offers his white horse to Khandoba as an act of repentance and asks for a boon. The boon is that he be present in every shrine of Khandoba, that human-kind is bettered and that he be given an offering of goat flesh. The boon is granted, and thus he transforms a demigod. Malla, when offered a boon, asks for the destruction of the world and human-flesh. Angered by the demon's request, Khandoba decapitates him, and his head falls at the temple stairs where it is trampled by the devotees feet. The legend further describes how two Lingas appeared at Prempuri, the place where the demons were killed.[16][17]

Oral stories continue the process of Sanskritization of Khandoba — his elevation from a folk deity to Shiva, a deity of the classical Hindu pantheon — that was initiated by the texts. Khandoba's wives Mhalsa and Banai are also identified with Shiva's classical Hindu wife, Parvati, and Ganga respectively. Hegadi Pradhan, the minister and brother-in-law of Khandoba and brother of Lingavat Vani Mhalsa,[18] the faithful dog that helps Khandoba kill the demons, the horse given by Mani and the demon brothers are considered avatars of Vishnu, Nandi and the demons Madhu-Kaitabha respectively. Other myth variants narrate that Khandoba defeats a single demon named Manimalla, who offers his white horse, sometimes called Mani, to the god.[19] Other legends depict Mhalsa (or Parvati) and Banai or Banu (or Ganga) as futilely helping Khandoba in the battle to collect the blood of Mani, every drop of which creates a new demon. Finally, the dog of Khandoba swallows all the blood. Sometimes, Mhalsa, or rarely Banai, is described as seated behind Khandoba on the horse and fighting with a sword or spear.[20]

The legends portray Khandoba as a king who rules from his fortress of Jejuri and holds court where he distributes gold. Also, king Khandoba goes on hunting expeditions, which often turn into "erotic adventures", and subsequent marriages.[21]

Wives

[edit]

Khandoba has several wives from different communities, who serve as cultural links between the god and the communities; Mhalsa and Banai (Banu, Banubai) being the most important.[21] While Khandoba's first wife Mhalsa is from the Lingayat merchant (Vani) community, his second wife Banai is a Dhangar (shepherd caste). Mhalsa has had a regular ritualistic marriage with Khandoba. Banai, on the other hand, has a love marriage by capture with the god. Mhalsa is described as jealous and a good cook; Banai is erotic, resolute, but does not even know how to cook. Often folk songs tell of their quarrels. Mhalsa represents "culture" and Banai "nature". The god king Khandoba stands between them.[22]

Khandoba's third wife, Rambhai Shimpin, is a tailor woman who was a heavenly nymph or devangana and is sometimes identified with Banai. She is a prototype of the Muralis — the girls "married" to Khandoba. Rambhai is worshipped as a goddess whom Khandoba visits after his hunt. She is also localised, being said to come from the village from Dhalewadi, near Jejuri. The fourth wife Phulai Malin, from the gardener or Mali caste, She was a particular Murali and is thus a deified devotee of Khandoba. She is visited by him at "Davna Mal" (field of southernwood, a herb said to be dear to Khandoba). The fifth wife, Candai Bhagavin, is a Telin, a member of the oilpresser caste. She is recognized as a Muslim by the Muslims. Apart from these, Muralis — girls offered to Khandoba — are considered as wives or concubines of the god.[23][24]

Other associations and identifications

[edit]

Mallana (Mallikaarjuna) of Andhra Pradesh and Mailara of Karnataka are sometimes identified with Khandoba (Mallari, Malhari, Mairala). Khandoba is also associated with Bhairava, who is connected with Brāhmanahatya (murder of a Brahmin).[25] Devotees emphasize that Khandoba is a full avatar of Shiva, and not a partial avatar like Bhairava or Virabhadra. He accepts the attributes of the demon king — his horse, weapons and royal insignia.[26]

Sontheimer stresses the association of Khandoba with clay and termite mounds. Oral legends tell of Khandoba's murtis being found in termite mounds or "made of earth".[27] According to Sontheimer, Martanda Bhairava (Khandoba) is a combination of the sun god Surya and Shiva, who is associated with the moon. Martanda ("blazing orb") is a name of Surya, while Bhairava is a form of Shiva.[24][28] Sundays, gold and turmeric, which are culturally associated with the sun, form an important part of the rituals of Khandoba.[24][28] Sontheimer associates the worship of the Sun as termite mounds for fertility and his role as a healer to Khandoba's role as granter of fertility in marriages and to the healing powers of turmeric, which the latter holds.[28]

Another theory identifies Kartikeya (Skanda) with Khandoba.[29] The hypotheses of the theory rests upon the similarities between Skanda and Khandoba, namely their association with mountains and war, similarity of their names and weapons (the lance of Skanda and the sword of Khandoba) and both having two principal wives.[30] Also the festivals for both deities, Champa Sashthi and Skanda Sashthi respectively for Khandoba and Skanda fall on the same day.[31] Other symbols associated with Khandoba are the dog and horse.[32]

Worship

[edit]

Though Shiva is worshipped across Maharashtra in his original form, some Maharashtrian communities prefer to worship him in form of his avatars, Khandoba being the most popular.[33] He is the most popular Kuladevata (family deity) in Maharashtra.[1] One of the most widely worshipped gods of the Deccan plateau, Khandoba is considered as "the premier god of Sakama bhakti (wish-granting devotion) and one of the most powerful deities responsive to vows (navas)".[33] He is worshipped by the vast majority of Marathi Hindu people from all strata of that society. He is the patron deity of warrior, farming, herding as well as some Brahmin (priest) castes, the hunters and gatherers of the hills and forests, merchants and kings. The devotees of Khandoba in the Deccan principally consists of Marathas (kshatriyas) and Kunabis, shepherd Dhangars, village guards and watchmen Ramoshis — a "Denotified tribe",[34][35] the former "untouchable" Mahars and Mangs, fisher-folk Kolis, balutedar castes like gardeners (Mali) and tailors (Shimpi), though it also includes of a few Brahmins and even some Muslims.[36][37] Although Brahmin presence is nominal in his sect, Deshastha Brahmins,[38][25][39] as well as the Kokanastha Brahmins - in Nashik and Satara - do worship Khandoba, some imitating the Deshastha Brahmins.[40] The Deshastha Brahmins, Chandraseniya Kayastha Prabhus,[39] as well as the royal families like Gaikwads and Holkars worship Khandoba as their Kuladevata. He is also worshipped by Jains and Lingayats. He is viewed as a "king" of his followers.[41]

Rituals and modes of worship

[edit]Khandoba is believed to be a kadak (fierce) deity, who causes troubles if not propitiated properly as per the family duties.[42] Khandoba is worshipped with Turmeric (Bhandār), Bel fruit-leaves, onions and other vegetables.[43] The deity is offered puran poli – a sweet or a simpler dish called bharit rodga of onion and brinjal.[44] A strict vegetarian naivedya (offering of food) is offered to Khandoba in the temples, although he is regarded by many devotees as a non-vegetarian.[4] Goat flesh is also offered to the deity, although this is done outside the temple as meat is forbidden inside the temple.[4]

An important part of the Khandoba-sect is navas, a vow to perform service to the god in return for a boon of good harvest, male child, financial success etc. On fulfilment of the navas, Khandoba was offered children or some devotees would afflict pain by hook-swinging or fire-walking.[45] This type of worship using navas is called Sakama Bhakti – worship done with an expectation of return and is considered "to be of a lower esteem".[46] But the most faithful bhaktas (devotees) are considered to be greedy only for the company of their Lord, Khandoba is also called bhukela – hungry for such true bhaktas in the Martanda Vijaya.[47]

Boys called Vāghyā (or Waghya, literally "tigers") and girls called Muraḹi were formerly dedicated to Khandoba, but now the practice of marrying girls to Khandoba is illegal.[43] The Vaghyas act as the bards of Khandoba and identify themselves with the dogs of Khandoba, while Muralis act as his courtesans (devanganas — nymphs or devadasis). The Vaghyas and their female counterparts Muralis sing and dance in honour of Khandoba and narrate his stories on jagarans — all night song-festivals, which are sometimes held after navas fulfilment.[45] Another custom was ritual-suicide by Viras (heroes) in the cult.[48] According to legend, an "untouchable" Mang (Matanga) sacrificed himself for the foundation of the temple at Jejuri to persuade Khandoba to stay at Jejuri forever.[47] Other practices in the cult include the belief that Khandoba possesses the body of a Vaghya or devrsi (shaman).[49][50] Another ritual in the cult is an act of chain-breaking in fulfilment of a vow or an annual family rite; the chain is identified with the snake around Shiva's neck, which was cut by the demons in the fight.[32] Another rite associated with the family duties to please Khandoba is the tali bharne, which is to be performed every full moon day. A tali (dish) is filled with coconuts, fruits, betel nuts, saffron, turmeric (Bhandar) and Bel leaves. Then, a coconut is placed on a pot filled with water and the pot is worshipped as an embodiment of Khandoba. Then, five persons lift the tali, place it repeatedly on the pot thrice, saying "Elkot" or "Khande rayaca Elkot". Then the coconut in the tali is broken and mixed with sugar or jaggery and given to friends and relatives. A gondhal is performed along with the tali bharne.[51]

Khandoba is considered as the giver of fertility. Maharashtrian Hindu couples are expected to visit a Khandoba temple to obtain Khandoba's blessing on consummation of marriage. Traditional Maharashtrian families also organize a jagaran as part of the marriage ceremony, inviting the god to the marriage.[8] The Sanskrit Malhari Mahatmya suggests offerings of incense, lights, betel and animals to Khandoba. The Marathi version mentions offerings of meat and the worship by chedapatadi – "causing themselves to be cut", hook-swinging and self-mortification by viras. Marathi version calls this form of bhakti (devotion) as ugra (violent, demonic) bhakti. The Martanda vijaya narrates about Rakshashi bhakti (demonic worship) by animal sacrifice and self — torture. Possession by Khandoba, in form of a wind, is lower demonic worship (pishachi worship). Sattvic worship, the purest form of worship, is believed to be feeding Khandoba in form of a Brahmin.[13]

Muslim veneration

[edit]Khandoba is also a figure of respect and worship to Muslims, and this affiliation is visible in the style of his temples. He is called Mallu or Ajmat Khan (Rautray) by Muslim devotees, and is many times portrayed as being a Muslim himself in this context.[52] The latter title is believed to conferred upon by the Mughal invader king Aurangzeb, who was forced to flee from Jejuri by Khandoba's power.[46] Some of these distinguishing Muslim features include his usual appearance as that of a pathan on horseback, one of his wives being a Muslim, and that his horse-keeper is a Muslim in Jejuri. The Martaṇḍa Vijaya expressly states that his devotees are mainly Muslims. The worship of Khandoba had received royal patronage by Ibrahim II, which consisted of the reinstatement of the annual jatra (fair) and the right of pilgrims to perform rituals at the Naldurg temple.[52] The Malhari Mahatmya even records Muslims (mleccha) as the god's bhaktas (devotees), who call him as Malluka Pathan or Mallu Khan.[53] In Jejuri, a Muslim family traditionally looks after the horses of the god.[46]

Temples

[edit]

There are over 600 temples dedicated to Khandoba in the Deccan.[33] His temples stretch from Nasik, Maharashtra in the north to Davangere, Karnataka in the south, Konkan, Maharashtra in the west to western Andhra Pradesh in the east. The eleven principal centres of worship of Khandoba or jagrut kshetras, where the deity is to be called awake or "jagrut", are recognized; six of them in Maharashtra and the rest in northern Karnataka.[33][36] Khandoba's temples resemble forts, the capital of his kingdom being Jejuri. The priests here are Guravs, not Brahmins.[6] His most important temples are:

- Jejuri: The foremost center of worship of Khandoba.[54] It is situated 48 km from Pune, Maharashtra. There are two temples: the first is an ancient temple known as Kadepathar. Kadepathar is difficult to climb. The second one is the newer and more famous Gad-kot temple, which is easy to climb. This temple has about 450 steps, 18 Kamani (arches) and 350 Dipmalas (lamp-pillars). Both temples are fort-like structures.[55]

- Pali (Rajapur) or Pali-Pember, Satara district, Maharashtra.[56]

- Adi-mailar or Khanapur (Pember or Mailkarpur) near Bidar, Karnataka

- Naldurg, Osmanabad district, Maharashtra.

- Mailara Linga, Dharwad district, Karnataka.

- Mangasuli, Belgaum district, Karnataka.

- Maltesh or Mailara temple at Devaragudda, Ranebennur Taluk, Haveri district, Karnataka.

- Mannamailar or Mailar (Mylara), Bellary, Karnataka.

- Nimgaon Dawadi, Pune district, Maharashtra.[57]

- Shegud, Ahmednagar district, Maharashtra.

- Komuravelli, Siddipet district, Telangana.

- Satare, Aurangabad district, Maharashtra.

- Malegaon, Nanded district, Maharashtra.

- Mailapur Mailarlingeshwara Temple, Mailapura, Yadgir, Yadgiri District, Karnataka

Festivals

[edit]

A six-day festival, from the first to sixth lunar day of the bright fortnight of the Hindu month of Margashirsha, in honour of Khandoba is celebrated at Jejuri, to commemorate the fight with demons Mani-Malla. On the sixth day (Champa-Shashthi), Khandoba is believed to have slew the demons.[43] A jatra (temple festival and fair) is held in Pember on Champa-shasthi; the festival continues until the new moon.[58] Deshastha Brahmans and Marathas also observe the annual Champa-Shashthi festival. The images of Khandoba and Malla are cleaned and worshipped. For six days, a fast is observed. On the seventh day, the devotees break their fast by a feast known as Champasashtliiche parne. An invitation to this feast is regarded as an invitation from Khandoba himself and is harder to refuse.[59]

Another festival Somvati Amavasya, which is a new-moon day that falls on a Monday, is celebrated in Jejuri. A palakhi (palanquin) procession of the images of Khandoba and Mhalsa is carried from the Gad-kot temple to the Karha river, where the images are ritually bathed.[60][61]

In Pali-Pember, the ritual of the marriage of Khandoba with Mhalsa is annually performed. Turmeric is offered to the deities.[48] Two festivals are celebrated in honour of Mailara, as Khandoba is known in Karnataka. These are the Dasara festival at Devaragudda, and an eleven-day festival in Magha month (February–March) in Mailar, Bellary district. Both festivals have enactments of the battle between Mailar and the demons Mani-Malla.[62] Chaitra Purnima (full-moon day) is also considered auspicious.[63]

In general, Sundays, associated with the Sun, are considered auspicious for Khandoba worship.[64]

Development of the sect

[edit]

The sect of Khandoba, a folk religion, reflects the effect of Vedic Rudra, the Puranic Shiva worshipped as Linga in Brahmanical Hinduism and Nath and Lingayat sects.[42] Khandoba may be a product of the Vedic Rudra, who like Khandoba was associated with robbers, horses and dogs.[65] The 14th-century commentator Sayana traces the name Malhari to the Taittiriya Samhita, Malhari is explained as enemy (ari) of Malha (Prajapati) – an epithet of Rudra, who is considered a rival of the deity Prajapati.[66] According to Stanley, Khandoba originated as a mountain-top god, solar deity and a regional guardian and then assimilated into himself gods of various regions and communities.[33] According to Stanley, Khandoba inherits traits from both the sun-god Surya as well as Shiva, who is identified with the moon. Stanley describes Khandoba as "a moon god, who has become a sun god", emphasizing on how the moon imagery of Shiva transforms into the solar iconography of Khandoba in the Malhari Mahatmya.[24]

As per R. C. Dhere, two stone inscriptions in 1063 C.E. and 1148 C.E mentioning the folk deities Mailara and his consort Malavva which suggests that Mailara gained popularity in Karnataka in this period. Soon, royals of this region started erecting temples to this folk deity, upsetting the elite class of established religion who vilified Mailara. Initially exalted as an incarnation of Shiva, Mailara was denounced by Basava, the founder of the Shiva-worshipping Lingayat sect – who would later promote the deity. Chakradhara (c.1270, founder of Mahanubhava sect), Vidyaranya (1296–1391) and Sheikh Muhammad (1560–1650) criticized the god.[67] The Varkari poet-saint Eknath also wrote "disparagingly" about Khandoba's cult worship,[46] but after him, the "open" criticism of Khandoba stopped, but the "barbaric" practices of his cult were still targeted.[67]

Sontheimer suggests that Khandoba was primarily a god of herdsmen,[68] and that the cult of Khandoba is at least older than 12th century, which can be determined by references in Jain and Lingayat texts and inscriptions. A 12th-century Jain author Brahmashiva claims that a Jain, who died in battle after a display of his valour, was later named as Mailara. By the 13th century, wide worship of Malhari or Mailara is observed by kings, Brahmins, simple folk and warriors. With the rise of the Muslim empire, classical Hindu temples fell into ruin, giving rise to the folk religion such as of Khandoba. Chakradhara remarked in his biography Lilacharitra - "by the end of the Kali Yuga, temples of Vishnu and Shiva will be destroyed, but those of Mairala will stay". A 1369 AD inscription at Inavolu near Warangal tells an account of Mallari different from the Malhari Mahatmya — Shiva helped the epic hero Arjuna kill the demon Malla, thus acquiring the title of Mallari. Mailara was the family deity of the Kakatiya dynasty (1083–1323 AD); a text from their rule records the self-torture rituals of Mailara-devotees and describes the deity. Throughout his development, Mailara is looked upon as a lower manifestation of Ishvara (God) by Lingayat and Maharashtrian bhakti saints.[66] By the 18th century, Khandoba had become the clan deity of the Maratha Empire. In 1752, the Maratha dowager queen Tarabai chose Khandoba's Jejuri temple to seal her pact with the Peshwa ruler, Balaji Bajirao, in the deity's presence.[69]

The Malhari Mahatmya states that Khandoba first appeared on Champa-Shashthi, which was a Sunday, at Premapur, which identified as Pember (Adimailar, Mailarapur) near Bidar. Marathi traditions tell that Khandoba came originally from Premapuri, now Pember in Karnataka, then went to Naldurg, Pali and finally to Jejuri.[12] Sontheimer suggests that the cult of Mailara may have originated in Pember and then spread to Maharashtra, merging with the cult of Khandaka — the patron yaksha (demi-god) of Paithan giving it its distinct Maharashtrain characteristics. Maharashtrains call the god – Kanadya Khanderaya, the god from Karnataka. The cult possibly was spread by Lingayat, Jain and other merchants, associated with Mailara-Khandoba, to other parts of the Deccan. Besides Mailara, Khandoba is identified with other deities of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, and is called as Mallanna, Mairala, and Mallu Khan.[70] Other traditions like Shakta sects of folk goddesses were assimilated into the Khandoba sect, identifying the goddesses with Khandoba's wives Mhalsa or Banai.[53]

Marathi literature has a mixed reaction to the sect of Khandoba. Naranjanamadhva (1790) in stotra (hymn) dedicated to Khandoba calls him "an illustrious king with rich clothes and a horse with a saddle studded with jewels", who was once "an ascetic beggar who ride an old bull and carried an ant-bitten club (khatvanga)" – a humorous take on the Puranic Shiva. In another instance (1855), he is called a ghost by a Christian missionary and aKoknastha Brahmin in a debate against a Deshastha Brahmin.[42] Another Brahmin remarks with scorn about the impurity of the Khandoba temple, visited by Shudras and whose priests are non-Brahmin Guravs.[42] The Marathi term "khel-khandoba", which is taken to mean "devastation" in general usage, refers to the possession of devotee by the god in his sect.[42]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Singh p.ix

- ^ Sontheimer in Hiltebeitel p.314

- ^ Sontheimer in Feldhaus p.115

- ^ a b c Stanley in Hiltebeitel p.284

- ^ Stanley in Hiltebeitel p.288

- ^ a b Sontheimer in Hiltebeitel p.303

- ^ Sontheimer in Hiltebeitel p.323

- ^ a b c Stanley (Nov. 1977) p. 32

- ^ For worship of Khandoba in the form of a lingam and possible identification with Shiva based on that, see: Mate, p. 176.

- ^ Sontheimer in Bakker p.103

- ^ Sontheimer in Bakker pp.105–6

- ^ a b Sontheimer in Bakker p.105

- ^ a b Sontheimer in Hiltebeitel p.330

- ^ Stanley in Hiltebeitel pp. 272,293

- ^ Sontheimer in Bakker p.118

- ^ Stanley in Hiltebeitel pp.272–77

- ^ For a detailed synopsis of Malhari Mahtmya, see Sontheimer in Bakker pp.116–26

- ^ Sontheimer in Hiltebeitel p.328

- ^ Stanley in Hiltebeitel p.278

- ^ Stanley in Hiltebeitel pp.280–4

- ^ a b Sontheimer in Feldhaus p.116

- ^ Sontheimer in Feldhaus p.117-8

- ^ Sontheimer in Feldhaus p. 118

- ^ a b c d Stanley (Nov. 1977) p. 33

- ^ a b Sontheimer in Hiltebeitel p. 300

- ^ Sontheimer in Hiltebeitel p.332

- ^ Sontheimer in Bakker p.110

- ^ a b c Sontheimer in Bakker p.113

- ^ For use of the name Khandoba as a name for Karttikeya in Maharashtra, Gupta Preface, and p. 40.

- ^ Khokar, Mohan (June 25, 2000). "In recognition of valour". The Hindu. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ Pillai, S Devadas (1997). Indian Sociology Through Ghurye, a Dictionary. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan. pp. 190–192. ISBN 81-7154-807-5.

- ^ a b Sontheimer in Bakker p.114

- ^ a b c d e Stanley (Nov. 1977) p. 31

- ^ Rathod, Motiraj (November 2000). "Denotified and Nomadic Tribes in Maharashtra". The Denotified and Nomatic Tribes Rights Action Group Newsletter (April–June and July–September, 2000). DNT Rights Action Group. Archived from the original on 2009-02-05.

- ^ Singh, K S (2004). People of India: Maharashtra. Popular Prakashan and Anthropological Survey of India. p. 1768.

- ^ a b Stanley in Hiltebeitel p.271

- ^ "Ahmadnagar District Gazetteer: People". Maharashtra State Gazetteer. 2006 [1976]. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ Shirish Chindhade (1996). Five Indian English Poets: Nissim Ezekiel, A.K. Ramanujan, Arun Kolatkar, Dilip Chitre, R. Parthasarathy. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 107. ISBN 978-81-7156-585-6.

- ^ a b Government of Maharashtra. "Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Ratnagiri and Savantvadi". Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ^ "Nashik District: Population". Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency. 2006 [1883]. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ Sontheimer in Bakker p.104

- ^ a b c d e Sontheimer in Hiltebeitel pp.332–3

- ^ a b c Underhill p.111

- ^ Stanley in Hiltebeitel p.296

- ^ a b Stanley in Hiltebeitel p.293

- ^ a b c d Burman p.1227

- ^ a b Sontheimer in Hiltebeitel p.313

- ^ a b Sontheimer in Hiltebeitel p.308

- ^ Sontheimer in Hiltebeitel p.302

- ^ See Stanley in Zelliot pp. 40–53: for details of possession beliefs: Angat Yene:Possession by the Divine

- ^ "Ratnagiri District Gazetteer : People: RELIGIOUS BELIEFS". Maharashtra State Gazetteer. 1962. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ a b Sontheimer in Hiltebeitel pp. 325–7

- ^ a b Sontheimer in Bakker p.116

- ^ For Jejuri as the foremost center of worship see: Mate, p. 162.

- ^ "Jejuri". Maharashtra Gazetteer. 2006 [1885].

- ^ "PAL OR RAJAPUR". Satara District Gazetteer. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ Nimgaon

- ^ Sontheimer in Bakker p.108

- ^ [A HISTORY OF THE MARATHA PEOPLE, C A. KINCAID, CV.O., I.CS. AND Rao Bahadur D. B. PARASNIS, VOL II, page 314, HUMPHREY MILFORD, OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS, 1922]

- ^ Sontheimer in Bakker p.127

- ^ See Stanley (Nov. 1977) pp. 34–38 for a detailed description

- ^ Stanley in Hiltebeitel p.314

- ^ See Stanley (Nov. 1977) p. 39

- ^ Stanley (Nov. 1977) p. 30

- ^ Sontheimer in Hiltebeitel pp.301–2

- ^ a b Sontheimer in Bakker pp. 106–7

- ^ a b Dhere, R. C. (2009). "FOLK GOD OF THE SOUTH: KHANDOBA – Chapter 1: "Mailar', that is Khandoba". official site of R C Dhere. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Sontheimer, Günther-Dietz (1989). Pastoral deities in western India. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Baviskar, B.S.; Attwood, D.W. (2013). Inside-outside : two views of social change in rural India. Los Angeles: SAGE. p. 250. ISBN 9788132113508. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ^ Sontheimer in Bakker pp.108–9

Further reading

[edit]- Burman, J. J. Roy (Apr 14–20, 2001). "Shivaji's Myth and Maharashtra's Syncretic Traditions". Economic and Political Weekly. 36 (14/15): 1226–1234. JSTOR 4410485.

- Gupta, Shakti M. (1988). Karttikeya: The Son of Shiva. Bombay: Somaiya Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 81-7039-186-5.

- Mate, M. S. (1988). Temples and Legends of Maharashtra. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- Singh, Kumar Suresh; B. V. Bhanu (2004). People of India. Anthropological Survey of India. ISBN 978-81-7991-101-3.

- Sontheimer, Günther-Dietz (1989). "Between Ghost and God: Folk Deity of the Deccan". In Alf Hiltebeitel (ed.). Criminal Gods and Demon Devotees: Essays on the Guardians of Popular Hinduism. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-88706-981-9.

- Sontheimer, Günther-Dietz (1990). "God as King for All: The Sanskrit Malhari Mahatmya and its context". In Hans Bakker (ed.). The History of Sacred Places in India as Reflected in Traditional Literature. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-09318-4.

- Sontheimer, Günther-Dietz (1996). "All the God's wives". In Anne Feldhaus (ed.). Images of Women in Maharashtrian Literature and Religion. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-2837-0.

- Stanley, John M. (Nov 1977). "Special Time, Special Power: The Fluidity of Power in a Popular Hindu Festival". The Journal of Asian Studies. 37 (1). Association for Asian Studies: 27–43. doi:10.2307/2053326. JSTOR 2053326.

- Stanley, John. M. (1988). "Gods, Ghosts and Possession". In Eleanor Zelliot, Maxine Berntsen (ed.). The Experience of Hinduism.

- Stanley, John. M. (1989). "The Captulation of Mani: A Conversion Myth in the Cult of Khandoba". In Alf Hiltebeitel (ed.). Criminal Gods and Demon Devotees: Essays on the Guardians of Popular Hinduism. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-88706-981-9.

- Underhill, Muriel Marion (1991). The Hindu Religious Year. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0523-3.

External links

[edit]- Website with full information about Lord Khandoba Archived 2018-11-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Khandoba temples of Maharashtra, Karnatak & Andhra Pradesh