Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mahavidya

View on Wikipedia

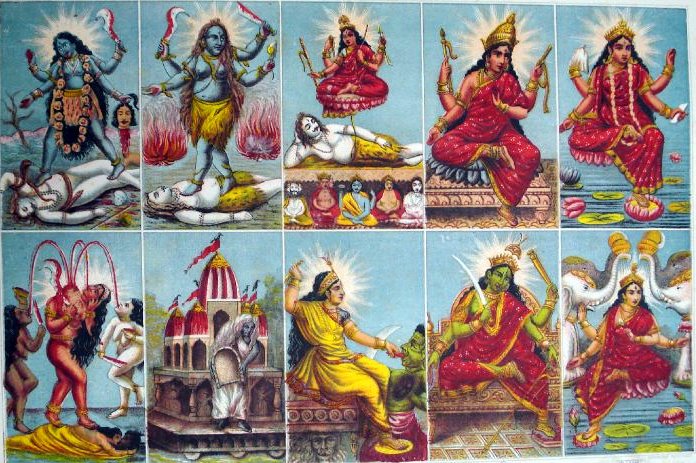

Bottom: Chhinnamasta, Dhumavati, Bagalamukhi, Matangi, and Kamala

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Shaktism |

|---|

|

|

|

The Mahavidya (Sanskrit: महाविद्या, IAST: Mahāvidyā, lit. Great Wisdoms) are a group of ten Hindu[1] Tantric goddesses.[2] The ten Mahavidyas are usually named in the following sequence: Kali, Tara, Tripura Sundari, Bhuvaneshvari, Bhairavi, Chhinnamasta, Dhumavati, Bagalamukhi, Matangi and Kamalatmika.[3] Nevertheless, the formation of this group encompass divergent and varied religious traditions that include yogini worship, Shaivism, Vaishnavism, and Vajrayana Buddhism.[2]

The development of the Mahavidyas represents an important turning point in the history of Shaktism as it marks the rise of the Bhakti aspect in Shaktism, which reached its zenith in 1700 CE. First sprung forth in the post-Puranic age, around 6th century CE, it was a new theistic movement in which the supreme being was envisioned as female. A fact epitomized by texts like Devi-Bhagavata Purana, especially its last nine chapters (31–40) of the seventh skandha, which are known as the Devi Gita, and soon became central texts of Shaktism.[4]

Names

[edit]Shaktas believe, "the one Truth is sensed in ten different facets; the Divine Mother is adored and approached as ten cosmic personalities," the Dasa-Mahavidya ("ten-Mahavidyas").[5] As per another school of thought in Shaktism Mahavidyas are considered to be forms of Mahakali, in others as forms of Tripura Sundari. The Mahavidyas are considered Tantric in nature, and are usually identified as:[6]

- Kali The goddess who is the ultimate form of Brahman, and the devourer of time (Supreme Deity of Kalikula systems). Mahakali is of a pitch black complexion, darker than the dark of the dead of the night. She has three eyes, representing the past, present and future. She has shining white, fang-like teeth, a gaping mouth, and her red, bloody tongue hanging from there. She has unbound, disheveled hairs. She wears tiger skin as her garment, a garland of skulls and a garland of red Hibiscus flowers around her neck, and on her belt, she was adorned with skeletal bones, skeletal hands as well as severed arms and hands as her ornamentation. She is Chaturbhuji (having four hands), two of them carry the Khadga (Ram-dao), or a sword and the Trishul and two others carry a demon head and a bowl collecting the blood dripping from a demon head.

- Tara The goddess who acts as a guide and a protector, and she who offers the ultimate knowledge that grants salvation. She is the goddess of all sources of energy. The energy of the sun is believed to originate from her. She manifested as the mother of Shiva after the incident of Samudra Manthana to heal him as her child. Tara is of a light blue complexion. She has disheveled hair, wearing a crown decorated with the digit of the half-moon. She has three eyes, a snake coiled comfortably around her throat, wearing the skins of tigers, and a garland of skulls. She is also seen wearing a belt supporting her skirt made of tiger-skin. Her four hands carry a lotus, scimitar, demon head and scissors. Her left foot rests on the laying down Shiva.

- Tripura Sundari (Shodashi, Lalita) The goddess who is "beauty of the three worlds" (Supreme Deity of Srikula systems); the "Tantric Parvati" or the "Moksha Mukta". She is the ruler of Manidvipa, the eternal supreme abode of the goddess. Shodashi is seen with a molten gold complexion, three placid eyes, a calm mien, wearing red and pink vestments, adorned with ornaments on her divine limbs and four hands, each holding a goad, lotus, a bow, and arrow. She is seated on a throne.

- Bhuvaneshvari The goddess as the world mother, or whose body comprises all the fourteen lokas of the cosmos. Bhuvaneshvari is of a fair, golden complexion, with three content eyes as well as a calm mien. She wears red and yellow garments, decorated with ornaments on her limbs and has four hands. Two of her four hands hold a goad and noose while her other two hands are open. She is seated on a divine, celestial throne.

- Bhairavi The fierce goddess. The female version of Bhairava. Bhairavi is of a fiery, volcanic red complexion, with three furious eyes, and disheveled hair. Her hair is matted, tied up in a bun, decorated by a crescent moon as well as adorning two horns, one sticking out from each side. She has two protruding tusks from the ends of her bloody mouth. She wears red and blue garments and is adorned with a garland of skulls around her neck. She also wears a belt decorated with severed hands and bones attached to it. She is also decked with snakes and serpents too as her ornamentation – rarely is she seen wearing any jewelry on her limbs. Of her four hands, two are open and two hold a rosary and book.

- Chhinnamasta ("She whose head is severed") – The self-decapitated goddess.[7] She chopped her own head off in order to satisfy Jaya and Vijaya (metaphors of rajas and tamas - part of the trigunas). Chinnamasta has a red complexion, embodied with a frightful appearance. She has disheveled hair. She has four hands, two of which hold a sword and another hand holding her own severed head; three blazing eyes with a frightful mien, wearing a crown. Two of her other hands hold a lasso and drinking bowl. She is a partially clothed lady, adorned with ornaments on her limbs and wearing a garland of skulls on her body. She is mounted upon the back of a copulating couple.

- Dhumavati The widow goddess. Dhumavati is of a smoky dark brown complexion, her skin is wrinkled, her mouth is dry, some of her teeth have fallen out, her long disheveled hair is gray, her eyes are seen as bloodshot and she has a frightening mien, which is seen as a combined source of anger, misery, fear, exhaustion, restlessness, constant hunger and thirst. She wears white clothes, donned in the attire of a widow. She is sitting in a horseless chariot as her vehicle of transportation and on top of the chariot, there is an emblem of a crow as well as a banner. She has two trembling hands, her one hand bestows boons and/or knowledge and the other holds a winnowing basket.

- Bagalamukhi The goddess who paralyzes enemies. Bagalamukhi has a molten gold complexion with three bright eyes, lush black hair and a benign mien. She is seen wearing yellow garments and apparel. She is decked with yellow ornaments on her limbs. Her two hands hold a mace or club and holds demon Madanasura by the tongue to keep him at bay. She is shown seated on either a throne or on the back of a crane.

- Matangi – The Prime Minister of Lalita (in Srikula systems), sometimes called Śyāmala ("dark in complexion", usually depicted as dark blue) and the "Tantric Saraswati". Matangi is most often depicted as emerald green in complexion, with lush, disheveled black hair, three placid eyes and a calm look on her face. She is seen wearing red garments and apparel, bedecked with various ornaments all over her delicate limbs. She is seated on a royal throne and she has four hands, three of which hold a sword or scimitar, a skull and a veena (a musical instrument). Her one hand bestows boons to her devotees.

- Kamala (Kamalatmika) she who dwells in lotuses; sometimes called the "Tantric Lakshmi". Kamala is of a molten gold complexion with lush black hair, three bright, placid eyes, and a benevolent expression. She is seen wearing red and pink garments and apparel and bedecked with various ornaments and lotuses all over her limbs. She is seated on a fully bloomed lotus, while with her four hands, two hold lotuses while two grant her devotees' wishes and assures protection from fear.

All these Mahavidyas reside in Manidvipa.

The Maha bhagavata Purana and Brihaddharma Purana however, list Shodashi (Sodasi) as Tripura Sundari, which is simply another name for the same goddess.[8]

The Todala-Tantra associates the Mahavidyas with the Dashavatara, the ten avatars of Vishnu, in chapter ten. They are as follows:[citation needed]

| No. | Mahavidya names | Dashavatara names |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Kali | Krishna |

| 2. | Tara | Matsya |

| 3. | Tripura Sundari | Parashurama |

| 4. | Bhuvaneshvari | Vamana |

| 5. | Bhairavi | Balarama |

| 6. | Chhinnamasta | Narasimha |

| 7. | Dhumavati | Varaha |

| 8. | Bagalamukhi | Kurma |

| 9. | Matangi | Rama |

| 10 | Kamala | Buddha |

The Guhyati guyha-tantra associates the Mahavidyas with the Dashavatara differently, and states that the Mahavidyas are the source from which the avatars of Vishnu arise.[citation needed]

| No. | Mahavidya names | Dashavatara names |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Kali | Krishna |

| 2. | Tara | Rama |

| 3. | Tripura Sundari | Kalki |

| 4. | Bhuvaneshvari | Varaha |

| 5. | Bhairavi | Narasimha |

| 6. | Chhinnamasta | Parashurama |

| 7. | Dhumavati | Vamana |

| 8. | Bagalamukhi | Kurma |

| 9. | Matangi | Buddha |

| 10 | Kamala | Matsya |

Note: In the above list do not get confused the names of Matanga Bhairava with Matanga Rishi, and Narada Bhairava with Narada Rishi.

Mention in Scriptures

[edit]Source:[9]

- Rudra Yamala Tantra: Describes the origin and powers of Dashamahavidya in detail.

- Tantrasara by Abhinavagupta: Philosophical and symbolic interpretations.

- Devi Bhagavatam: Especially Book 7 elaborates the divine play of Devi as Dashamahavidya.

- Kalika Purana: Details the worship of Kali and other Mahavidyas.

- Brahmanda Purana: Refers to Lalita Tripura Sundari as the head of all Mahavidyas.

- Shakta Upanishads: Reference to the symbolic aspects of Mahavidyas, especially Matangi and Chhinnamasta.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kinsley (1997), pp. ix, 1.

- ^ a b Shin (2018), p. 316.

- ^ Shin (2018), p. 17.

- ^ Brown, Charles Mackenzie (1998). The Devī Gītā: The Song of the Goddess. SUNY Press. p. 23. ISBN 9780791439401.

- ^ Shankarnarayanan, S (1972). The Ten Great Cosmic Powers: Dasa Mahavidyas (4 ed.). Chennai: Samata Books. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9788185208381.

- ^ Kinsley (1997), p. 302.

- ^ Daniélou, Alain (1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. pp. 284–290. ISBN 978-0-89281-354-4.

- ^ Kinsley, David R (1987). Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. Motilal Banarsidass Publication. pp. 161–165. ISBN 9788120803947.

- ^ "The Dashamahavidya: The Ten Great Wisdom Goddesses of Hindu Tantric Tradition". Story Teller. May 3, 2025.

Works cited

[edit]- Kinsley, David R. (1997). Tantric Visions of the Divine Feminine: The Ten Mahavidyas. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520204997.

- Shin, Jae-Eun (2018). Change, Continuity and Complexity: The Mahavidyas in East Indian Sakta Traditions. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-32690-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Shin, Jae-Eun (2010). "Yoni, Yoginis and Mahavidyas : Feminine Divinities from Early Medieval Kamarupa to Medieval Koch Behar". Studies in History. 26 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1177/025764301002600101. S2CID 155252564.

External links

[edit] Media related to Mahavidya at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mahavidya at Wikimedia Commons

Mahavidya

View on Grokipedia- Kali: The primordial goddess of time and destruction, depicted as dark-skinned and fierce, symbolizing the dissolution of ignorance and the path to transcendence.[3]

- Tara: The compassionate savior, shown blue and holding a scissors, representing protection and the crossing of existential oceans toward enlightenment.[3]

- Tripura Sundari (Shodashi): The youthful beauty of the three worlds, embodying harmony and supreme bliss, often associated with the Sri Yantra for manifestation of desires aligned with dharma.[2]

- Bhuvaneshvari: The sovereign of the universe, portrayed as serene and expansive, signifying the vastness of creation and the nurturing aspect of cosmic order.[1]

- Bhairavi: The fierce mother, red-hued and adorned with skulls, invoking fiery energy to burn away impurities and foster inner strength.[3]

- Chinnamasta: The self-decapitated goddess, illustrating the transcendence of body and ego through self-sacrifice, depicted with her severed head drinking her own blood.[3]

- Dhumavati: The widow goddess of smoke and inauspiciousness, symbolizing detachment from material life and the wisdom gained through loss and solitude.[2]

- Bagalamukhi: The paralyzer of enemies, golden and crane-faced, granting control over speech and mind to silence negativity and illusions.[1]

- Matangi: The outcast goddess of speech and music, green-skinned and associated with pollution, representing the acceptance of all aspects of life for holistic wisdom.[3]

- Kamala: The lotus-seated one akin to Lakshmi, embodying abundance and purity, guiding toward prosperity and the integration of spiritual and material realms.[2]

Etymology and Terminology

Etymology

The term "Mahavidya" is derived from Sanskrit, where "maha" signifies "great" or "supreme," and "vidya" denotes "knowledge," "wisdom," or "science," collectively translating to "Great Wisdom" or "Great Knowledge."[4] This compound reflects the profound, all-encompassing insight into the divine feminine principle, positioning the Mahavidyas as embodiments of ultimate truth beyond ordinary learning.[5] In Tantric contexts, Mahavidya represents esoteric wisdom that transcends conventional education, offering liberating insight into the nature of reality through contemplative practices on the goddess forms.[4] These wisdoms serve as instruments for spiritual seekers to attain supernormal powers and deeper comprehension of cosmic unity, emphasizing transformative knowledge rather than mundane skills.[6] Historically, the term appears in texts like the Devi-Bhagavata Purana, where it denotes manifestations of the goddess Shakti as forms of divine feminine knowledge, emerging during her interactions with Shiva to illustrate varied aspects of supreme reality.[4] This usage underscores the Mahavidyas' role in Shakta theology as transcendent revelations of the Divine Mother.[7] Unlike other "vidya" concepts, such as the 64 yogini arts (chausath yogini kalas), which encompass practical techniques in performance, crafts, and sciences for worldly mastery in Tantric and Kaula traditions, Mahavidya specifically focuses on the goddess aspects embodying metaphysical and occult wisdom.[6] The 64 yoginis represent a broader group of semi-divine female powers often serving as attendants to the Great Goddess, tied to regional tantric cults, whereas the Mahavidyas form a distinct set of ten supreme wisdom deities.[6]List of the Ten Mahavidyas

The Ten Mahavidyas represent ten manifestations of the Divine Mother in Tantric Hinduism, embodying distinct forms of great wisdom, with "Mahavidya" etymologically signifying "great knowledge." These goddesses are central to Shakta Tantra practices, guiding devotees through various aspects of spiritual realization. The standard sequence of the Ten Mahavidyas, as outlined in key Tantric scriptures such as the Todala Tantra, is as follows, with each accompanied by a brief identifier denoting her primary symbolic role:- Kali: The devourer of time, embodying ultimate destruction and transformation.[3]

- Tara: The savior and guide, who leads devotees across the ocean of existence.[3]

- Tripura Sundari (or Shodashi): The beauty of the three worlds, representing perfection and supreme harmony.[3]

- Bhuvaneshvari: The sovereign of the universe, symbolizing the expansive power of creation.[3]

- Bhairavi: The fierce protector, associated with fiery energy and awe-inspiring power.[3]

- Chhinnamasta: The self-decapitated goddess, signifying radical self-sacrifice and enlightenment.[3]

- Dhumavati: The widow of smoke, embodying inauspiciousness and detachment from worldly illusions.[3]

- Bagalamukhi: The crane-faced controller, who paralyzes enemies and stills the mind.[3]

- Matangi: The outcaste goddess of speech, harnessing the power of polluted wisdom and arts.[3]

- Kamala: The lotus-born one, denoting prosperity, fertility, and auspicious abundance.[3]

Historical and Scriptural Origins

Early Mentions in Puranas and Tantras

The concept of the Mahavidyas emerged around the 6th century CE within post-Puranic Shaktism, representing a pivotal shift toward envisioning the supreme being as feminine and embodying diverse aspects of cosmic power and wisdom. This development integrated earlier goddess worship traditions with Tantric elements, elevating the Devi as the ultimate reality from which all creation arises. Scholarly analyses trace this conceptualization to a synthesis of Puranic narratives and emerging Tantric doctrines, emphasizing the Mahavidyas' role in transcending conventional dualities of creation and dissolution.[5] The Devi-Bhagavata Purana, composed between the 9th and 10th centuries CE, provides one of the earliest comprehensive references to the ten Mahavidyas as distinct forms of the Devi. In the Devi Gita (Book 7), the goddess reveals herself as the eternal source of all existence, manifesting in tenfold aspects to illustrate her omnipresence and supremacy over the Trimurti. These forms are invoked as embodiments of her infinite vidya (knowledge), with verses highlighting their emergence to aid devotees in spiritual liberation, such as in descriptions of worship practices that align with Shakta rituals. The text underscores their unity as extensions of the singular Devi, countering patriarchal interpretations of divinity prevalent in contemporaneous Vaishnava and Shaiva traditions.[10][11] Tantric scriptures further elaborate the Mahavidyas' cosmological significance, portraying them as active forces in the universe's unfolding. The Rudra Yamala Tantra, a key Shaiva-Shakta text likely from the medieval period, details their origin, powers, and esoteric worship, including mantras and yantras for invoking their transformative energies. It positions the Mahavidyas as integral to the dialogue between Shiva and Shakti, facilitating the sadhaka's ascent through kundalini practices. Similarly, the Kalika Purana (10th-11th century CE) depicts them as manifestations during the cosmic creation process, with Kali as the primordial form emerging from the Devi's wrathful aspect to regulate time and dissolution. Verses in this Purana describe their sequential appearance to balance the triad of creation (srishti), preservation (sthiti), and destruction (samhara), integrating them into broader narratives of divine intervention in the material world.[12][13] The Mundamala Tantra offers nuanced linkages between the Mahavidyas and Shiva's aspects, equating each goddess with a corresponding form of the deity to symbolize the inseparability of consciousness (Shiva) and energy (Shakti). For instance, specific verses correlate Kali with Mahakala, Tara with Akshobhya, and others to Rudra-like manifestations, portraying the ten as counterparts that enable Shiva's cosmic functions. This Tantric framework, emphasizing their role in transcending ego and illusion, reinforces the Mahavidyas' status as pathways to non-dual realization, distinct from purely devotional Puranic portrayals.[14][15]Evolution in Shaktism

The concept of the Mahavidyas within Shaktism transitioned from sporadic Puranic references to a more structured Tantric framework between the 10th and 12th centuries CE, marking a pivotal shift toward emphasizing esoteric practices and the multifaceted nature of divine feminine energy. Early foundational mentions in texts like the Devi Bhagavata Purana provided mythological origins, such as Sati's manifestation into the ten forms to challenge Shiva, but it was Tantric scriptures that systematized them as a complete pantheon representing supreme knowledge and power.[16] The Guhyatiguhya Tantra, a key medieval Tantric text, played a central role in this systematization by enumerating the ten Mahavidyas and integrating them into ritual and yogic frameworks, thereby elevating Shaktism's focus on goddess-centered soteriology over earlier Vedic or Puranic emphases.[17] Regional traditions significantly shaped the Mahavidyas' development, particularly in eastern India, where Bengal and Assam became hubs for Shakta Tantric worship by the medieval period. In these areas, the goddesses were adapted into local folk and tribal practices, blending with indigenous mother goddess cults to foster a vibrant devotional landscape that extended to communal observances. This regional influence led to the establishment of dedicated worship sites by the 12th-16th centuries, reflecting the Mahavidyas' growing accessibility beyond elite Tantric circles and their role in unifying diverse Shakta communities.[16] The Mahavidyas were further integrated into broader Hindu sects, influencing Shaiva and Vaishnava traditions through syncretic interpretations that highlighted their compatibility with existing theologies. In Shaivism, forms like Bhairavi were paired with Shiva's fierce manifestations, such as Bhairava, to underscore the union of masculine and feminine principles in Tantric rituals. Similarly, Vaishnava adaptations linked the ten goddesses to Vishnu's Dashavatara, as outlined in texts like the Guhyatiguhya Tantra, positing the Mahavidyas as the originating sources of the avatars and thereby asserting Shaktism's primacy within pan-Hindu frameworks.[17] This incorporation facilitated the Mahavidyas' dissemination across sects, promoting a more inclusive Tantric Shaktism by the late medieval era.[16] Modern scholars view the Mahavidyas as a post-6th century CE assertion of feminine divinity, building on the Devi Mahatmya's establishment of the Great Goddess while challenging patriarchal norms through their diverse, often transgressive iconography. David Kinsley, in his analysis of Tantric Shaktism, argues that this evolution reflects a deliberate Tantric strategy to empower the feminine as the ultimate reality, countering earlier androcentric tendencies in Hindu theology. Other researchers, such as those examining eastern Indian traditions, emphasize how the Mahavidyas' development post-6th century facilitated women's agency in spiritual practices, transforming Shaktism into a dynamic force for gender equilibrium in medieval Hinduism.Descriptions of the Ten Mahavidyas

Kali

Kali is the first and foremost among the ten Mahavidyas in the standard Tantric enumeration, embodying the primal force of consciousness that initiates the spectrum of divine feminine wisdom.[1] In her iconic Tantric representations, Kali possesses pitch-black skin, signifying the boundless void and the dissolution of form, with disheveled hair and a protruding tongue that alludes to her absorption of all creation. She is portrayed with four arms wielding a sword for severing ignorance, a trishula (trident) to pierce illusions, a severed head representing the ego's decapitation, and a blood-filled bowl symbolizing the life force she consumes and transforms. Adorned with a garland of fifty human skulls—one for each letter of the Sanskrit alphabet—and a skirt of severed arms denoting the actions of karma, she stands with her right foot on Shiva's chest, asserting her dynamic supremacy over the passive male principle. This fearsome visage, often naked to denote transcendence of societal norms, underscores her role as the ultimate destroyer within the cycle of existence.[18] Symbolically, Kali personifies kala (time), the inexorable devourer that annihilates the temporal ego and attachments, paving the way for the apprehension of eternal reality beyond duality. Her black complexion evokes the primal womb of creation, where destruction and renewal coalesce, while her stance over Shiva illustrates the triumph of Shakti over inertia, urging devotees toward ego-dissolution and non-dual awareness. As the devourer of demons and illusions, she embodies the raw, unmediated power that confronts and liberates through terror, transforming fear into enlightenment.[1] Kali's unique attributes as a Mahavidya highlight her as the fierce, untamed expression of Shakti, distinct in her unapologetic ferocity that shatters conventional piety and enforces direct confrontation with mortality and the self. In Tantric practice, her seed mantra (bija) is "Kṛṃ," invoking her transformative energy, while an extended mantra—"Kṛṃ Kṛṃ Kṛṃ Hūṃ Hūṃ Hrīṃ Hrīṃ Dakṣiṇe Kālike Kṛṃ Kṛṃ Kṛṃ Hūṃ Hūṃ Hrīṃ Hrīṃ Svāhā"—amplifies invocation for protection and liberation. The associated Kali Yantra features an eight-petaled lotus enclosing a central bindu (point) where Kali resides, encircled by eight directional yoginis, facilitating meditation on her all-encompassing presence and the numerological harmony of cosmic forces.[18]Tara

Tara is the second of the ten Mahavidyas in the Hindu Tantric tradition, positioned after Kali and embodying a compassionate yet fierce aspect of the Divine Mother that guides devotees across the ocean of samsara toward liberation.[19] As a manifestation of Adi Shakti, she represents the power to transcend worldly illusions and fears, often invoked for protection and spiritual crossing, with her name deriving from the Sanskrit root tṛ, meaning "to cross over." In her iconography, Tara is depicted as a youthful goddess with dark blue or black skin, symbolizing the infinite void and boundless compassion, and three eyes denoting her omniscience. She has four arms, holding a sword or scimitar for severing ignorance, scissors or a chopper (kartri) to cut attachments, a blue lotus representing purity and enlightenment, and a skull cup (kapala) signifying the transcendence of ego. Adorned with a garland of severed heads, disheveled matted hair, snake ornaments, and a tiger-skin garment, she stands with her left foot on the chest of a supine Shiva lying on a corpse in a cremation ground, emphasizing her dominion over death and time.[19] This form, detailed in Tantric texts like the Phetkarini Tantra and Sadhanamala, distinguishes her from other Mahavidyas through the scissors, a unique emblem of precise liberation from bonds. Symbolically, Tara functions as the "star goddess," illuminating the path through darkness and aiding the soul's passage beyond duality and illusion, much like a celestial guide navigating perilous waters. Her blue lotus evokes the rarity and transcendence of spiritual awakening, while her fierce posture on the corpse underscores the compassionate ferocity required to dismantle ego-driven suffering. In Tantric visualization, she embodies the energy that dissolves worldly attachments, fostering inner freedom without destruction, as opposed to Kali's more overt annihilative force.[19] Tara's unique attributes include her maternal compassion blended with wrathful protection, often manifesting as forms like Ugratar (fierce Tara) or Nila Sarasvati (blue Sarasvati), where she nurtures while subduing obstacles. Though sharing iconographic parallels with Buddhist Tara, the Hindu Tantric Tara is distinctly an autonomous source of shakti, emphasizing empowerment through esoteric knowledge rather than solely salvific mercy. She is particularly associated with protection from the eight great fears—such as fire, poison, and wild animals—granting devotees safety in crises, and with speech as Nila Sarasvati, bestowing eloquence, wisdom, and defense against verbal harms or disputes.[19]Tripura Sundari

Tripura Sundari, also known as Shodashi or Lalita, is the third of the ten Mahavidyas in the Shakta Tantric tradition, embodying the divine feminine's aspect of transcendent beauty and harmony. Her name, meaning "the beautiful one of the three worlds" or "Tripura," signifies her dominion over the physical, astral, and causal realms, representing the ultimate aesthetic and spiritual perfection that unites all existence.[20] As the youthful goddess of supreme bliss, she is depicted in her eternal sixteen-year-old form, symbolizing perpetual vitality and the bloom of cosmic consciousness.[21] In her iconography, Tripura Sundari possesses a radiant golden complexion, evoking the luster of divine illumination, and appears as a youthful maiden seated gracefully on a throne or the Sri Yantra. She has four arms, holding a goad (ankusha) to guide devotees toward truth, a lotus flower representing purity and enlightenment, a sugarcane bow symbolizing the mind's curvature toward desire, and arrows made of flowers denoting the five senses directed by divine will.[20] Often adorned with jewels and a crescent moon in her crown, her serene expression and elegant posture contrast with the fiercer forms of preceding Mahavidyas, emphasizing poise and allure.[22] The symbolism of Tripura Sundari centers on the beauty of the three worlds (Tripura), where she harmonizes the material and spiritual planes through her embodiment of ananda (supreme bliss). She is intrinsically linked to the Sri Yantra, a sacred geometric diagram of nine interlocking triangles that maps the universe's structure, serving as her visual mantra and a tool for meditation on cosmic unity.[20] This yantra encapsulates her role as the source of creation's aesthetic order, where the central bindu (point) represents the unmanifest divine from which all forms emanate.[21] As the embodiment of pure consciousness (chit), Tripura Sundari holds a central position in the Sri Vidya tradition, a refined Tantric path that venerates her as the supreme Shakti through mantra and yantra worship.[22] In this lineage, she guides practitioners to realize non-dual awareness, transcending ego and illusion. Her unique attribute lies in balancing the cycles of creation, preservation, and dissolution, complementing Shiva's static consciousness with her dynamic energy to sustain the universe's eternal rhythm.[20] Through this equilibrium, she fosters spiritual liberation by integrating beauty, power, and wisdom.[21]Bhuvaneshvari

Bhuvaneshvari, the fourth in the sequence of the ten Mahavidyas, embodies the sovereign ruler of the cosmos, often regarded as the divine mother who governs the expanse of creation.[23] Her name derives from "Bhuvana," meaning the universe or world, and "Ishvari," signifying the supreme mistress, highlighting her role as the sustainer of all existence. In Tantric traditions, she represents the material realm infused with divinity, where the physical world is not separate from the sacred but an expression of cosmic harmony.[24] In iconographic depictions, Bhuvaneshvari is portrayed with a fair or golden complexion, symbolizing purity and radiance, and a serene, smiling face framed by flowing black hair. She has four arms, two of which hold a goad (ankusha) for guiding devotees toward righteousness and a noose (pasha) for binding ignorance and negative forces, while the other two display gestures of fearlessness (abhaya mudra) and granting boons (varada mudra). Adorned with a crescent moon on her forehead, which evokes the cycles of time and renewal, she is seated in a lotus posture, representing spiritual enlightenment emerging from the material world. Her feminine form often includes full breasts from which milk flows, underscoring her nurturing essence.[25][23] Symbolically, Bhuvaneshvari personifies the sovereignty over space (akasha) and the entire material universe, transforming the perceived void into a realm of divine fullness and potential. She integrates the five elements (bhutas) into a cohesive cosmic order, illustrating how the tangible world serves as a sacred space for realization. Her attributes blend the nurturing aspect of a mother goddess—providing sustenance and protection—with the profound equanimity that encompasses both emptiness (shunya) and abundance, reminding devotees of the unity between form and formlessness.[25][26] Within Tantric cosmology, Bhuvaneshvari connects to the bindu, the primordial point of concentrated energy from which the universe unfolds, as seen in her yantra where the central bindu signifies the core of creative power and the origin of manifestation. This association positions her as the expansive force that actualizes the bindu's potential into the vastness of bhuvana, bridging the subtle and gross aspects of reality.[27][25]Bhairavi

Bhairavi, the fifth of the ten Mahavidyas, embodies a terrifying yet enlightening aspect of the Divine Mother, serving as a fierce protector and illuminator in Shakta Tantra. Her name, derived from "bhairava" meaning "terrifying" or "fierce," underscores her role as the ultimate destroyer of fear and illusion, surpassing even male deities in power and wisdom. As one of the central figures in tantric traditions, she represents the transformative force that annihilates ignorance, guiding devotees toward spiritual liberation through confrontation with the ego. In her iconography, Bhairavi is depicted with fiery red skin symbolizing intense energy and passion, three eyes denoting omniscience, and disheveled hair signifying unbound wildness. She possesses four arms: the upper right holding a rosary for devotion and mantra recitation, the lower right displaying the abhaya mudra (gesture of fearlessness), while the left hands grasp a book representing sacred knowledge and a sword for severing delusions, with the lower left displaying the varada mudra (gesture of boon-granting). Often adorned with a garland of severed heads and seated on a corpse in a cremation ground, her form evokes both dread and reverence, with a complexion likened to a thousand suns radiating transformative light.[28][29] Symbolically, Bhairavi personifies the fierce knowledge that incinerates ignorance like fire consumes darkness, embodying the power of consciousness (jnana shakti) to dissolve attachments and reveal ultimate truth. Her association with cremation grounds highlights the impermanence of the material world and the purifying fire of spiritual death and rebirth, where the ego is reduced to ashes to allow enlightenment to emerge. This fiery essence underscores her as the embodiment of tapas (austerity and inner heat), facilitating profound inner alchemy.[28] In tantric practices, Bhairavi plays a pivotal role in kundalini awakening, igniting the dormant serpent energy at the base of the spine to rise through the chakras, burning away blockages and fears along the path. Her midway position among the Mahavidyas symbolizes a balance between the destructive ferocity of the earlier goddesses like Kali and the benevolent grace of later ones like Kamala, harmonizing terror and transcendence in the seeker's journey.[28]Chhinnamasta

Chhinnamasta, the sixth of the ten Mahavidyas, is depicted as a fierce, self-decapitated goddess embodying radical transformation and the transcendence of ego. Her iconography features a red complexion symbolizing vitality and the regenerative power of blood, with a nude form adorned by a garland of skulls and serpents around her neck. She possesses four arms: the upper right holding a sword used to sever her own head, the upper left grasping a lasso representing the binding of desires, the lower right supporting her severed head which drinks from one of three jets of blood gushing from her neck, and the lower left holding a drinking bowl or skull cup to capture the blood. Flanked by two female attendants, Dakini and Varnini, who drink the other two blood streams, she stands triumphantly upon a copulating couple—typically Kama (the god of desire) and Rati—emphasizing her dominion over primal forces.[30][31][5] The symbolism of Chhinnamasta's severed head centers on the control of the senses and the mastery of prana, the vital life force, illustrating the interruption and redirection of ego-driven attachments. By decapitating herself, she represents the ultimate act of self-sacrifice, severing the illusion of a separate self to achieve unity with the divine, where the headless form signifies liberation from dualistic perceptions and the flow of kundalini energy through the central subtle channel (sushumna). This paradoxical imagery of nourishment—her blood sustaining her head and attendants—highlights the cycle of life force generation, where destruction fuels renewal and spiritual awakening.[32][30][31] As an embodiment of sexual energy and life force, Chhinnamasta uniquely channels raw vitality into transcendent power, standing as a pivotal figure in the Mahavidya sequence for her role in catalyzing profound inner change. Her form paradoxically nourishes while demanding sacrifice, underscoring the tantric principle that ego dissolution leads to boundless awareness. In tantric interpretation, the copulating couple beneath her (maithuna) symbolizes the harnessing of sexual union not for mere pleasure, but as a disciplined practice to awaken and control kundalini shakti, transforming base desires into the elixir of enlightenment.[32][30][5]Dhumavati

Dhumavati is the seventh of the ten Mahavidyas, embodying the inauspicious and renunciatory dimensions of the divine feminine in Tantric Shaktism. She is depicted as a widow goddess, symbolizing the smoky remnants of dissolution and the detachment from worldly attachments. Her form represents the transformative power of misfortune into spiritual wisdom, emphasizing impermanence and the void that follows destruction.[33] In her iconography, Dhumavati appears as an emaciated, elderly widow with a gaunt, pale complexion, disheveled hair, and few teeth, often dressed in tattered white garments symbolizing mourning and poverty. She has two or four arms, typically holding a winnowing basket (supi) that signifies destitution and the scattering of illusions, along with a skull bowl, spear, or broom; in some depictions, she makes the abhaya mudra (fear-not gesture). Her vehicle is a crow, associated with death and the scavenging of remains, and she is sometimes shown riding a horseless chariot or seated on a corpse in desolate places like cremation grounds. This imagery underscores her connection to old age, frailty, and the inevitable decay of the physical form.[33] Symbolically, Dhumavati, whose name means "the smoky one," evokes the haze of cremation fires and the ephemeral nature of existence, teaching devotees to embrace loss and inauspiciousness as paths to liberation. She personifies the tamas guna (quality of inertia and darkness), linked to misfortune, solitude, and the rejection of material pleasures, yet through her worship, she imparts wisdom about the transience of life and the ultimate void (shunyata) after cosmic dissolution. As one of the later Mahavidyas, she marks a shift toward introspective, ascetic forms that confront the harsh realities of aging and annihilation. Her unique attribute lies in transforming apparent negativity—such as widowhood and poverty—into profound insight, guiding practitioners toward detachment and enlightenment beyond dualities.Bagalamukhi

Bagalamukhi, the eighth of the ten Mahavidyas, embodies the divine power to stun, paralyze, and control adversarial forces, serving as a potent force for protection and triumph in Tantric traditions.[34] Known also as Pitambara Devi, she represents the stambhana shakti, or the energy that immobilizes negativity, enemies, and disruptive thoughts, enabling practitioners to achieve stillness amid chaos.[3] In her iconography, Bagalamukhi is depicted with a radiant golden-yellow complexion, seated majestically on a golden throne, often holding a club in her right hand to smash the mouth of a demon symbolizing ignorance or malice, while her left hand pulls or restrains its tongue to silence harmful speech.[3] This two-armed form emphasizes her focused intervention, contrasting with more multi-limbed depictions in other Mahavidyas, and she is sometimes shown with a crane-like face, evoking the bird's poised stillness.[34] Symbolically, Bagalamukhi's crane-faced aspect signifies paralysis and restraint, granting control over speech, opponents, and internal distractions, thereby fostering victory in disputes and legal battles within Tantric practices.[34] Her unique attributes include the stilling of mental chatter and the invocation of magical powers to neutralize planetary influences or enmity, making her a guardian against verbal and psychic aggression.[3] Deeply associated with the vibrant yellow hue of turmeric, which denotes purity and transformative energy, Bagalamukhi aligns with the solar plexus region, symbolizing personal empowerment and the fiery will to overcome obstacles.[35]Matangi

Matangi, the ninth Mahavidya in the Tantric pantheon, embodies the transformative power of knowledge derived from the fringes of society, serving as a counterpart to Sarasvati in her more conventional form by embracing the impure and the overlooked aspects of learning, arts, and speech. Often regarded as the outcaste goddess, she symbolizes the integration of marginalized wisdom into spiritual practice, challenging orthodox notions of purity while granting devotees mastery over eloquence, music, and creative expression. Her role highlights the Tantric principle that true insight can emerge from what is deemed polluted or forbidden, positioning her as a deity who elevates the voices of the disenfranchised. In her iconography, Matangi is typically portrayed with an emerald-green complexion, evoking the vibrant, untamed growth of wisdom beyond societal boundaries, and four arms wielding a sword for severing ignorance, a skull cup representing the transcendence of death, a veena to signify musical and artistic dominion, and a noose (pasa) for binding ignorance. She is seated upon a corpse, underscoring her association with the liminal spaces between life and death, or sometimes on a throne adorned with jewels, and is often shown with disheveled hair, a garland of lotuses, and a parrot companion symbolizing articulate speech. These attributes, drawn from Tantric texts like the Matanga Tantra, emphasize her dual nature as both serene and subversive.[36] Symbolically, Matangi represents the acceptance of "polluted" knowledge—such as that from unclean places, leftover offerings, or outcaste experiences—as a valid path to profound understanding, contrasting with the refined learning of mainstream traditions. Her worship, prescribed in Tantric sadhanas, involves rituals in impure settings without the need for ritual bathing, using offerings like uneaten food or even menstrual blood to invoke her blessings for poetic inspiration, control over adversaries, and supernatural eloquence. This symbolism underscores her as a goddess who democratizes wisdom, making it accessible beyond elite castes.[36] Matangi's unique attributes as the patron of music, spoken word, and the arts extend to her embrace of the marginalized, including associations with unclean environments and the periphery of society, where she is invoked for empowerment through unconventional means. Her cult links closely to tribal and folk traditions, particularly among South Indian communities like the Madigas, a Scheduled Caste group with Dravidian roots, where pre-Hindu tribal worship of a mountain-climbing deity named Matangi was gradually assimilated into the broader Hindu framework during medieval periods, blending indigenous practices with Tantric Shaktism. This integration reflects folk rituals involving nature worship and oral storytelling, preserving her as a symbol of resilience for hunter-gatherer and low-caste groups.Kamala

Kamala, the tenth and final Mahavidya in the Tantric pantheon, embodies prosperity, beauty, and the harmonious integration of material and spiritual abundance. As the Tantric counterpart to Lakshmi, she is depicted with a radiant golden complexion, symbolizing divine illumination and auspiciousness, and is often shown seated in the lotus posture (padmasana) on a full-blooming lotus throne, which underscores her sovereignty and detachment from worldly impurities.[37] Her iconography features four arms: the upper pair holds lotuses, representing spiritual purity and enlightenment, while the lower pair displays the varada mudra (granting boons) and abhaya mudra (dispelling fear), signifying her benevolence in bestowing wealth, fertility, and protection. She is typically portrayed with a smiling face, three lotus-like eyes, firm breasts adorned with pearl garlands, and a resplendent crown, necklace, and kaustubha gem, evoking the rising sun's luster. Four majestic elephants pour streams of nectar over her from golden vessels, emphasizing royal opulence and the nourishment of both physical and metaphysical realms. This form integrates the lotus's symbolism of rising untainted from mud—purity amid prosperity—and positions Kamala as a bridge between earthly fulfillment and divine grace.[37][38] In the sequence of Mahavidyas, Kamala culminates the progression toward siddhi, or perfected realization, transforming the fierce initiatory energies of earlier goddesses into manifested abundance and bliss. Her unique attributes as Tantric Lakshmi highlight the Tantric ideal of non-duality, where material riches serve spiritual evolution rather than binding the soul, allowing devotees to achieve holistic liberation through devotion and ritual.[37][39]Mythological Narratives

The Legend of Sati and Shiva

In Hindu mythology, the origin of the Mahavidyas is rooted in the legend of Sati, the daughter of Daksha Prajapati and the devoted consort of Shiva, who married him despite her father's vehement disapproval due to Shiva's ascetic lifestyle and unconventional status.[40] Daksha, seeking to assert his authority and humiliate Shiva, organized a grand yajna (sacrificial ritual) to which he invited all deities and sages except Shiva and Sati, deliberately excluding them as an act of patriarchal defiance.[41] Upon learning of the event from the sage Narada, Sati insisted on attending to confront her father, but Shiva, foreseeing the dishonor and potential catastrophe, firmly refused to grant permission, advising her against participating in an inauspicious gathering marked by enmity.[42] Enraged by Shiva's denial and determined to exercise her divine will, Sati transcended her mortal guise and manifested her supreme aspect as Adi Shakti, the primordial feminine energy, transforming into the ten Mahavidyas to encircle and overpower Shiva from all ten cardinal and intermediate directions, thereby compelling him to yield.[40] These forms emerged to block Shiva's path and unveil the multifaceted nature of the Divine Mother, each Mahavidya representing a distinct facet of cosmic power, wisdom, and transcendence that even Shiva, the lord of yoga, could not resist.[41] The legend, as recounted in the Devi-Bhagavata Purana, underscores the Mahavidyas' emergence as an assertion of feminine autonomy and divine sovereignty against patriarchal exclusion and control, transforming Sati's personal grievance into a universal demonstration of Shakti's supremacy.[40] Variations appear in Tantric texts, such as the Shakta Maha-Bhagavata Purana, where Sati's fury directly births the forms to surround Shiva, and the Shakti Sangama Tantra, which links one manifestation, Dhumavati, to the smoke of Sati's impending self-immolation at the yajna.[41] Having manifested the Mahavidyas, Sati proceeded to Daksha's sacrifice, where she endured further insults to Shiva before immolating herself in the sacred fire, an act that precipitated Shiva's profound grief and the subsequent cosmic events.[40]Individual Myths and Associations

Myths associated with each Mahavidya vary across Tantric texts and Puranas, with the following representing common narratives. KaliIn the Devi Mahatmya, a key text in the Markandeya Purana, Kali emerges from Durga's forehead during the battle against the demon Raktabija, whose blood drops spawn identical clones upon touching the ground; Kali defeats him by drinking all his blood to prevent further multiplication, ultimately slaying him as the goddesses dance in triumph.[43][44] This myth underscores Kali's role as a fierce protector, while her name derives from kala, signifying time, associating her with the inexorable cycles of creation, preservation, and dissolution in Hindu cosmology.[45] Tara

According to tantric narratives, Tara manifests to rescue the world from the demon Hayagriva, who disrupts cosmic order by devouring the Vedas; she subdues him through her compassionate yet fierce intervention, restoring knowledge and harmony.[46] This protective role parallels her depiction in Buddhist tantra as a savior figure who guides beings across the ocean of samsara, highlighting shared Indo-Tibetan motifs of feminine wisdom overcoming ignorance and demonic forces.[46][47] Tripura Sundari

In the Tripura Rahasya and related Puranic accounts, Tripura Sundari, also known as Lalita, orchestrates the destruction of the three demon cities (Tripura) built by Maya for the sons of Taraka, which align evilly once every thousand years; Shiva, as Tripurantaka, arrows them at her command, symbolizing the triumph over ego and illusion.[48] She is depicted as the consort of Shiva in his form as Kameshwara, the lord of desire, embodying the harmonious union of Shakti and Shiva in tantric cosmology.[49] Bhuvaneshvari

Tantric scriptures, such as the Bhuvaneshvari Tantra, describe Bhuvaneshvari as the sovereign of the universe who creates infinite worlds from her own body, with space (akasha) emerging from her form to encompass all manifestation and sustain cosmic expansion.[23] This act of self-generated creation positions her as the matrix of reality, where her gracious presence nurtures the physical world and its diverse realms.[50] Bhairavi

In tantric traditions, Bhairavi is the consort of Bhairava, a fierce form of Shiva, embodying fiery energy to purify and transform; she is closely associated with Tripura Bhairavi, the fierce aspect that conquers the three realms of illusion, tied to the dissolution phase of existence.[51][52] Chhinnamasta

A prominent myth in tantric lore recounts Chhinnamasta, an aspect of Parvati, severing her own head with a sword to feed her starving attendants Jaya and Vijaya (or Dakini and Varnini) with jets of blood from her neck, symbolizing the ultimate maternal self-sacrifice for sustenance and enlightenment.[53] This act, drawn from texts like the Chhinnamasta Tantra, links her to the Vedic motif of regenerative sacrifice, where life force is renewed through apparent destruction.[54] Dhumavati

As narrated in the Pranatoshini Tantra, Dhumavati originates as a cursed form of Parvati when, in extreme hunger, she swallows Shiva whole; upon regurgitating him at his plea, Shiva curses her to embody widowhood and inauspiciousness, transforming her into the smoky residue of burnt illusions.[55] In this state, she is wedded to Shiva as the embodiment of disease and dissolution, representing the harsh realities of loss and transcendence beyond worldly attachments.[41] Bagalamukhi

According to tantric lore, the goddess emerges from a divine lake (Haridra Sarovara) during a catastrophic storm unleashed by the demon Madanasura, who uses the power of speech to incite chaos; Bagalamukhi seizes his tongue, stilling the tempest and paralyzing his destructive forces to restore universal order.[56] This myth illustrates her role as the silencer of enmity and the upholder of equilibrium against verbal and elemental turmoil. Matangi

In tantric narratives from the Matangi Tantra, Matangi appears as an outcaste (chandali) form of Saraswati, born from the leftovers of Shiva's meal or as a polluted aspect rejected by society, yet she gains divine favor by serving in Shiva's court as the goddess of inner wisdom and ecstatic knowledge.[57] Her myth emphasizes the transcendence of purity taboos, positioning her as the patron of arts, music, and forbidden speech that unlocks profound truths.[58] Kamala

Drawing from Puranic accounts akin to the Lakshmi myth in the Vishnu Purana, Kamala emerges from the churning of the cosmic ocean (Samudra Manthan), bestowing wealth and prosperity upon the gods; as a Mahavidya, she retains this origin while associating closely with Vishnu as his consort, symbolizing abundance and spiritual fulfillment.[59][60] This oceanic birth underscores her role in material and divine grace, bridging Vaishnava and Shakta traditions.[38]