Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Vāyu | |

|---|---|

| Member of the Pancha Bhuta and Dikpala | |

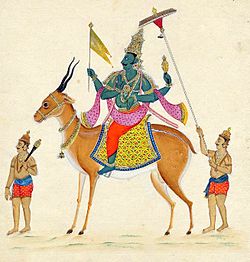

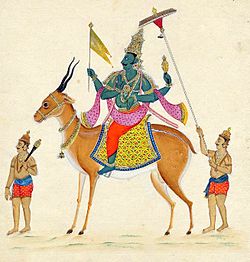

Vayu on his Vahana. | |

| Other names | Anila (अनिल) Pávana (पवन) Vyāna (व्यान) Vāta (वात) Tanūna (तनून) Mukhyaprāṇa (मुख्यप्राण) Bhīma (भीम) Maruta (मारुत) |

| Devanagari | वायु |

| Sanskrit transliteration | Vāyu |

| Affiliation | Deva |

| Abode | Vayu Loka, Satya Loka |

| Mantra | Om Vayave Namaha |

| Weapon |

|

| Mount | Chariot drawn by Horses, Gazelle |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents |

|

| Consort |

|

| Children | Mudā Apsaras (daughters)[1] Hanuman (son) Bhima (son) |

| Equivalents | |

| Indo-European | H₂weh₁yú |

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Vayu (Sanskrit: वायु, romanised: Vāyu, lit. 'Wind/Air'; Sanskrit pronunciation: [ʋaːju]), also known as Vata (Sanskrit: वात, romanised: Vāta, lit. 'Wind/Air') and Pavana (Sanskrit: पवन, romanised: Pávana, lit. 'Purifier'),[9] is the Hindu god of the winds as well as the divine messenger of the gods. In the Vedic scriptures, Vayu is an important deity and is closely associated with Indra, the king of gods. He is mentioned to be born from the breath of Supreme Being Vishvapurusha and also the first one to drink Soma.[10] The Upanishads praise him as Prana or 'life breath of the world'. In the later Hindu scriptures, he is described as a dikpala (one of the guardians of the direction), who looks over the north-west direction.[11][12] The Hindu epics describe him as the father of the god Hanuman and Bhima.[13]

The followers of the 13th-century saint Madhva believe their guru as an incarnation of Vāyu.[14][15][16] They worship the wind deity as Mukhyaprana (Sanskrit: मुख्यप्राण, romanised: Mukhyaprāṇa, lit. 'Chief Prana') and consider him as the son of the god Vishnu.

Connotations

[edit]The word for air (vāyu) or wind (pavana) is one of the classical elements in Hinduism. The Sanskrit word Vāta literally means 'blown'; Vāyu, 'blower' and Prāna, 'breathing' (viz. the breath of life, cf. the *an- in animate). Hence, the primary referent of the word is the 'deity of life', who is sometimes for clarity referred to as Mukhya-Vāyu (the chief Vayu) or Mukhya Prāna (the chief of life force or vital force).[17]

Sometimes the word vāyu, which is more generally used in the sense of the physical air or wind, is used as a synonym for prāna.[18] Vāta, an additional name for the deity Vayu, is the root of vātāvaranam, the Sanskrit and Hindi term for 'atmosphere'.[19]

Hindu texts and philosophy

[edit]

In the Rigveda, Vayu is associated with the winds, with the Maruts being described as being born from Vayu's belly. Vayu is also the first god to receive soma in the ritual, and then he and Indra share their first drink.[20][21] In the hymns, Vayu is 'described as having "exceptional beauty" and moving noisily in his shining coach, driven by two or forty-nine or one-thousand white and purple horses. A white banner is his main attribute'.[9] Like the other atmospheric deities, he is a 'fighter and destroyer', 'powerful and heroic'.[22]

In the Upanishads, there are numerous statements and illustrations of the greatness of Vayu. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad says that the gods who control bodily functions once engaged in a contest to determine who among them is the greatest. When a deity such as that of vision would leave a man's body, that man would continue to live, albeit as a blind man and having regained the lost faculty once the errant deity returned to his post. One by one the deities all took their turns leaving the body, but the man continued to live on, though successively impaired in various ways. Finally, when Mukhya Prāna started to leave the body, all the other deities started to be inexorably pulled off their posts by force, 'just as a powerful horse yanks off pegs in the ground to which he is bound'. This caused the other deities to realise that they can function only when empowered by Vayu, and can be overpowered by him easily. In another episode, Vayu is said to be the only deity not afflicted by demons of sin who were on the attack. This Vayu is "Mukhya Prana Vayu".[23] The Chandogya Upanishad says that one cannot know Brahman except by knowing Vayu as the udgitha (the mantric syllable om).[24]

Vayu is also one of the Vasus, a group of eight deities mentioned in Ramayana, Mahabharata and Vedas.[25] Within this categorisation, Vayu is also known as Anila.[25]

Avatars

[edit]

American Indologist Philip Lutgendorf says, "According to Madhva whenever Vishnu incarnates on earth, Mukhya Prana/Vayu accompanies him and aids his work of preserving dharma. Hanuman the friend and helper of Rama in the Treta Yuga, the strongman Bhima in Mahabharata, set at the end of Dvapara Yuga and Madhva in the Kali Yuga. Moreover, since the deity himself does not appear on earth until the end of kali age, the incarnate Vayu/Madhva serves during this period as the sole 'means' to bring souls to salvation".[26] Vayu is also known as Pavana and Matharishwa.

In the Mahabharata, Bhima was the spiritual son of Vayu and played a major role in the Kurukshetra War. He utilised his huge power and skill with the mace for supporting Dharma.

- The first avatar of Vayu is considered to be Hanuman. His stories are told in Ramayana. Since Hanuman is the spiritual son of Vayu he is also called Pavanaputra 'son of Pavana' and Vāyuputra. Today, Pavan is a fairly common Hindu name.

- The second avatar of Vayu is Bhima, one of the Pandavas appearing in the epic the Mahabharata.[27]

- Madhvacharya, is considered as the third avatar of Vayu. Madhva declared himself as an avatar of Vayu and showed the verses in Rigveda as a proof.[28][29][30] Author C. Ramakrishna Rao says, "Madhva explained the Balitha Sukta in the Rigveda as referring to the three forms of Vayu".[31]

Buddhism

[edit]In East Asian Buddhism, Vayu is a dharmapāla and often classed as one of the Twelve Devas (Japanese: 十二天, romanised: Jūniten) grouped together as directional guardians. He presides over the northwest direction.[32]

In Japan, he is called Fūten (風天). He is included with the other eleven devas, which include Taishakuten (Śakra/Indra), Katen (Agni), Enmaten (Yama), Rasetsuten (Nirṛti/Rākṣasa), Ishanaten (Īśāna), Bishamonten (Vaiśravaṇa/Kubera), Suiten (Varuṇa) Bonten (Brahmā), Jiten (Pṛthivī), Nitten (Sūrya/Āditya) and Gatten (Candra).[33]

See also

[edit]| Classical elements |

|---|

- List of wind deities

- Maruts

- Rudras

- Rudra, the Vedic wind or storm God

- Vayu Purana

- Vayu-Vata

- Nusa Bayu

- Fūjin, Shinto Kami of winds

- Aeolus

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Mani, Vettam (1975). Puranic encyclopaedia : a comprehensive dictionary with special reference to the epic and Puranic literature. Robarts - University of Toronto. Delhi : Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-0-8426-0822-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Jeffrey R. Timm (1 January 1992). Texts in Context: Traditional Hermeneutics in South Asia. SUNY Press. p. 113. ISBN 9780791407967.

- ^ Khagendranath Mitra (1952). The Dynamics of Faith: Comparative Religion. University of Calcutta. p. 209.

Brahmā and Vāyu are the sons of Vishnu and Lakshmi.

- ^ Satyavrata Ramdas Patel (1980). Hinduism, Religion and Way of Life. Associated Publishing House. p. 124. ISBN 9780686997788.

The Supreme Being, Vishnu or Nārāyana, is the personal first cause. He is the Intelligent Governor of the world and lives in Vaikuntha along with Lakshmi, His consort. He and His consort Lakshmi are real. Brahma and Vāyu are His two sons.

- ^ Muir, J. (6 June 2022). Original Sanskrit Texts on the Origin and History of The People of India: Volume Fifth. BoD – Books on Demand. ISBN 978-3-375-04617-0.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (15 May 2013). "On the description of Prakṛti [Chapter 1]". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ Gaṇeśa Harī Khare; Madhukar Shripad Mate; G. T. Kulkarni (1974). Studies in Indology and Medieval History: Prof. G. H. Khare Felicitation Volume. Joshi & Lokhande Prakashan. p. 244.

In Vayu and other Puranas, Vayudeva (different from Astadikpala Vayu), next to Brahma in grade, is also said to have five heads like Siva and Brahma and his consort is Bharatidevi.

- ^ M. V. Krishna Rao (1966). Purandara and the Haridasa Movement. Karnatak University. p. 200.

- ^ a b Eva Rudy Jansen; Tony Langham (1993), The book of Hindu imagery: The Gods and their Symbols, Binkey Kok Publications, ISBN 978-90-74597-07-4,

God of the wind ... also known as Vata or Pavan ... exceptional beauty ... moves on noisily in his shining coach ... white banner ...

- ^ Jamison, Stephanie W.; Brereton, Joel P. (2014). The Rigveda: The Earliest Religious Poetry of India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-937018-4.

- ^ Williams, George M. (27 March 2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oup USA. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2.

- ^ Chandra, Suresh (1998). Encyclopaedia of Hindu Gods and Goddesses. Sarup & Sons. ISBN 978-81-7625-039-9.

- ^ Daniélou, Alain (December 1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. ISBN 9780892813544.

- ^ Jeffery D. Long (9 September 2011). Historical Dictionary of Hinduism. Scarecrow Press. p. 187. ISBN 9780810879607.

Born near Udipi in Karnataka, where he spent most of his life, Madhva is believed by his devotees to be the third incarnation or avatāra of Vāyu, the Vedic god of the wind (the first two incarnations being Hanuman and Bhīma).

- ^ Ravi Prakash (15 January 2022). Religious Debates in Indian Philosophy. K.K. Publications. p. 176.

According to tradition, Madhvacarya is believed to be the third incarnation of Vayu (Mukhyaprana), after Hanuman and Bhima.

- ^ R. K. Madhukar (1 January 2014). Gayatri: The Profound Prayer. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 90. ISBN 978-8178-22467-1.

Vayu is accorded the status of a deva, an important God in the ancient literature. Lord Hanuman, who is considered to be one of the avatars of Vayudeva, is described as Mukhyaprana.

- ^ Subodh Kapoor (2002). Indian Encyclopaedia, Volume 1. Genesis Publishing Pvt Ltd. p. 7839. ISBN 9788177552577.

Mukhya Prana - The chief vital air

- ^ Raju, P.T. (1954), "The concept of the spiritual in Indian thought", Philosophy East and West, 4 (3): 195–213, doi:10.2307/1397554, JSTOR 1397554.

- ^ Vijaya Ghose; Jaya Ramanathan; Renuka N. Khandekar (1992), Tirtha, the treasury of Indian expressions, CMC Limited, ISBN 978-81-900267-0-3,

... God of the winds ... Another name for Vayu is Vata (hence the present Hindi term for 'atmosphere, 'vatavaran). Also known as Pavana (the purifier), Vayu is lauded in both the ...

- ^ Stephanie Jamison (2015). The Rigveda –– Earliest Religious Poetry of India. Oxford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0190633394.

- ^ Rigveda,Mandala 1,Hymn 2

- ^ Sukumari Bhattacharji (1984), Literature in the Vedic age, K.P. Bagchi,

... The other atmospheric gods are his associates: Vayu-Vatah, Parjanya, the Rudras and the Maruts. All of them are fighters and destroyers, they are powerful and heroic ...

- ^ Shoun Hino; K. P. Jog (1995). Bṛhadāraṇyakopaniṣadbhāṣya. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 158. ISBN 9788120812833.

Vāyu indicates Mukhya Prāṇa.

- ^ Chandogya Upanishad, Adhyaya XVIII, Verse 4; http://www.swamij.com/upanishad-chandogya.htm

- ^ a b Mani, Vettam; Mani, Vettam (2010). Purāṇic encyclopaedia: a comprehensive work with special reference to the epic and Purānic literature. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 978-81-208-0597-2.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, p. 67.

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 1: Adi Parva: Sambhava Parva: Section LXVII".

- ^ History of the Dvaita School and Its literature, pg 173

- ^ "Balittha Suktha -Text From Rig Veda". raghavendramutt.org. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016.

- ^ Indian Philosophy & Culture, Volume 15. The Institute. 1970. p. 24.

- ^ Chintagunta Ramakrishna Rao (1960). Madhva and Brahma Tarka. Majestic Press. p. 9.

- ^ "Twelve Heavenly Deities (Devas)". Nara National Museum, Japan. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ "juuniten 十二天". JAANUS. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- Vanamali, V (2010). Hanuman: The Devotion and Power of the Monkey God. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1594779145.

- Sholapurkar, G. R. (1992), Saints and Sages of India, Bharatiya Vidya Prakashan, ISBN 9788121700498

External links

[edit] Media related to Vayu at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Vayu at Wikimedia Commons