Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Maratha Empire

View on Wikipedia

The Maratha Empire,[a][12][13][14] also referred to as the Maratha Confederacy, was an early modern polity in the Indian subcontinent. It comprised the realms of the Peshwa and four major independent Maratha states[15][16] under the nominal leadership of the former.

Key Information

The Marathas were a Marathi-speaking peasantry group from the western Deccan Plateau (present-day Maharashtra) that rose to prominence under leadership of Shivaji (17th century), who revolted against the Bijapur Sultanate and the Mughal Empire for establishing "Hindavi Swarajya" (lit. 'self-rule of Hindus').[17][18] The religious attitude of Emperor Aurangzeb estranged non-Muslims, and the Maratha insurgency came at a great cost for his men and treasury.[19][20] The Maratha government also included warriors, administrators, and other nobles from other Marathi groups.[21] Shivaji's monarchy, referred to as the Maratha Kingdom,[22] expanded into a large realm in the 18th century under the leadership of Peshwa Bajirao I. Marathas from the time of Shahu I recognised the Mughal emperor as their nominal suzerain, similar to other contemporary Indian entities, though in practice, Mughal politics were largely controlled by the Marathas between 1737 and 1803.[b][23][24][c][26][27][d]

After Aurangzeb's death in 1707, Shivaji's grandson Shahu under the leadership of Peshwa Bajirao revived Maratha power and confided a great deal of authority to the Bhat family, who became hereditary peshwas (prime ministers). After he died in 1749, they became the effective rulers. The leading Maratha families – Scindia, Holkar, Bhonsle, and Gaekwad – extended their conquests in northern and central India and became more independent. The Marathas' rapid expansion was halted with the great defeat of Panipat in 1761, at the hands of the Durrani Empire. The death of young Peshwa Madhavrao I marked the end of Peshwa’s effective authority over other chiefs in the empire.[29][30][31] After he was defeated by the Holkar dynasty in 1802, the Peshwa Baji Rao II sought protection from the British East India Company, whose intervention destroyed the confederacy by 1818 after the Second and Third Anglo-Maratha Wars.

The structure of the Maratha state was that of a confederacy of four rulers under the leadership of the Peshwa at Poona (now Pune) in western India. These were the Scindia, the Gaekwad based in Baroda, the Holkar based in Indore and the Bhonsle based in Nagpur.[32][33] The stable borders of the confederacy after the Battle of Bhopal in 1737 extended from modern-day Maharashtra[34] in the south to Gwalior in the north, to Orissa in the east[35] or about a third of the subcontinent.[citation needed]

Nomenclature

[edit]This section may incorporate text from a large language model. (September 2025) |

The Maratha Empire is also referred to as the Maratha Confederacy. Historian Barbara Ramusack notes, "neither term is fully accurate since one implies a substantial degree of centralisation and the other signifies some surrender of power to a central government and a longstanding core of political administrators".[36] Historian Stewart Gordon argues against using the term "confederacy" because it implies long-term, stable power-sharing, which did not characterize the Maratha state. Instead, power dynamics within the Maratha leadership frequently changed, sometimes as often as each decade.[37]

Some scholars prefer the term "Maratha Raj" or "Maratha rule," emphasizing the state's unique blend of centralized and decentralized authority.[38] This structure enabled both territorial expansion and regional autonomy.[39]

Colonial historians occasionally used terms such as the Hindu Confederacy or the Indian Confederacy when referring to the coalition of the Maratha chiefs.[40][41]

Although at present, the word Maratha refers to a traditionally Marathi peasantry group, in the past the word has been used to describe all Marathi people.[42][43]

History

[edit]Shivaji and his descendants

[edit]

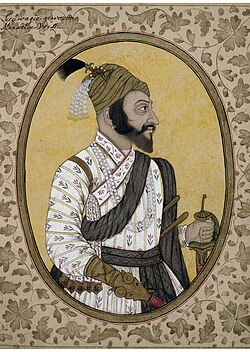

Shivaji (1630–1680) was a Maratha aristocrat of the Bhonsle clan and was the founder of the Maratha state.[44] Shivaji led a resistance against the Sultanate of Bijapur in 1645 by winning the fort Torna, followed by many more forts, placing the area under his control and establishing Hindavi Swarajya (self-rule of Hindu people[18]). He created an independent Maratha state with Raigad as its capital[45] and successfully fought against the Mughals to defend his kingdom. He was crowned as Chhatrapati (sovereign) of the new Maratha Kingdom in 1674.[citation needed]

The Maratha dominion under him comprised about 4.1% of the subcontinent, but it was spread over large tracts. At the time of his death,[44] it was reinforced with about 300 forts, and defended by about 40,000 cavalries, and 50,000 soldiers, as well as naval establishments along the west coast. Over time, the kingdom would increase in size and heterogeneity;[46] by the time of his grandson's rule, and later under the Peshwas in the early 18th century, it became a vast realm.[47]

Shivaji had two sons: Sambhaji and Rajaram, who had different mothers and were half-brothers. In 1681, Sambhaji succeeded to the crown after his father's death and resumed his expansionist policies. Sambhaji had earlier defeated the Portuguese and Chikka Deva Raya of Mysore. To nullify the alliance between his rebel son, Akbar, and the Marathas,[48] Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb headed south in 1681. With his entire imperial court, administration and an army of about 500,000 troops, he proceeded to expand the Mughal empire, gaining territories such as the sultanates of Bijapur and Golconda. During the eight years that followed, Sambhaji led the Marathas successfully against the Mughals.[49][page needed]

In early 1689, Sambhaji called his commanders for a strategic meeting at Sangameshwar to consider an onslaught on the Mughal forces. In a meticulously planned operation, Ganoji and Aurangzeb's commander, Mukarrab Khan, attacked Sangameshwar when Sambhaji was accompanied by just a few men. Sambhaji was ambushed and captured by the Mughal troops on 1 February 1689. He and his advisor, Kavi Kalash, were taken to Bahadurgad by the imperial army, where they were executed by the Mughals on 21 March 1689.[50] Aurangzeb had charged Sambhaji with attacks by Maratha forces on Burhanpur.[51]

Upon Sambhaji's death, his half-brother Rajaram ascended the throne. The Mughal siege of Raigad continued, and he had to flee to Vishalgad and then to Gingee for safety. From there, the Marathas raided Mughal territory, and many forts were recaptured by Maratha commanders such as Santaji Ghorpade, Dhanaji Jadhav, Parshuram Pant Pratinidhi, Shankaraji Narayan Sacheev and Melgiri Pandit. In 1697, Rajaram offered a truce but this was rejected by Aurangzeb. Rajaram died in 1700 at Sinhagad. His widow, Tarabai, assumed control in the name of her son Shivaji II.[52]

After Aurangzeb died in 1707, Shahu, the son of Sambhaji (and grandson of Shivaji), was released by Bahadur Shah I, the new Mughal emperor. However, his mother was kept a hostage of the Mughals to ensure that Shahu adhered to the release conditions. Upon release, Shahu immediately claimed the Maratha throne and challenged his aunt Tarabai and her son. The spluttering Mughal-Maratha war became a three-cornered affair. This resulted in two rival seats of government being set up in 1707 at Satara and Kolhapur by Shahu and Tarabai respectively. Shahu appointed Balaji Vishwanath as his Peshwa.[53] The Peshwa was instrumental in securing Mughal recognition of Shahu as the rightful heir of Shivaji and the Chhatrapati of the Marathas.[53] Balaji also gained the release of Shahu's mother, Yesubai, from Mughal captivity in 1719.[54]

During Shahu's reign, Raghoji Bhonsle expanded the kingdom eastwards. Khanderao Dabhade and later his son, Triambakrao, expanded it Westwards into Gujarat.[55] Peshwa Bajirao and his three chiefs, Udaji Pawar, Malharrao Holkar, and Ranoji Scindia expanded it northwards.[56]

Peshwa era

[edit]

Shahu appointed Balaji Vishwanath as Peshwa in 1713. Balaji Vishwanath's first major achievement was the conclusion of the Treaty of Lonavala in 1714 with Kanhoji Angre, the most powerful naval chief on the Western Coast who later accepted Shahu as Chhatrapati. In 1719, Marathas under Balaji marched to Delhi with Sayyid Hussain Ali, the Mughal governor of Deccan, and deposed the Mughal emperor, Farrukhsiyar.[57] The new teenage emperor, Rafi ud-Darajat and a puppet of the Sayyid brothers, granted Shahu rights to collecting Chauth and Sardeshmukhi from the six Mogul provinces of Deccan, and full possession of the territories controlled by Shivaji in 1680.[58][59] After Balaji Vishwanath's death in April 1720, his son, Baji Rao I, was appointed Peshwa by Shahu. Bajirao is credited with expanding the Maratha Kingdom tenfold from 3% to 30% of the modern Indian landscape during 1720–1740.[60] The Battle of Palkhed was a land battle that took place on 28 February 1728 at the village of Palkhed, near the city of Nashik, Maharashtra, India between Baji Rao I and Qamar-ud-din Khan, Asaf Jah I of Hyderabad. The Marathas defeated the Nizam. The battle is considered an example of the brilliant execution of military strategy.[57] In 1737, Marathas under Bajirao I raided the suburbs of Delhi in a blitzkrieg in the Battle of Delhi (1737).[61][62] The Nizam set out from the Deccan to rescue the Mughals from the invasion of the Marathas, but was defeated decisively in the Battle of Bhopal.[63][64] The Marathas extracted a large tribute from the Mughals and signed a treaty which ceded Malwa to the Marathas.[65] The Battle of Vasai was fought between the Marathas and the Portuguese rulers of Vasai, a village lying on the northern shore of Vasai creek, 50 km north of Mumbai. The Marathas were led by Chimaji Appa, brother of Baji Rao. The Maratha victory in this war was a major achievement of Baji Rao's time in office.[63]

Baji Rao's son, Balaji Bajirao (Nanasaheb), was appointed as the next Peshwa by Shahu despite the opposition of other chiefs. In 1740, the Maratha forces, under Raghoji Bhonsle, came down upon Arcot and defeated the Nawab of Arcot, Dost Ali, in the pass of Damalcherry. In the war that followed, Dost Ali, one of his sons Hasan Ali, and several other prominent people died. This initial success at once enhanced Maratha prestige in the south. From Damalcherry, the Marathas proceeded to Arcot, which surrendered to them without much resistance. Then, Raghuji invaded Trichinopoly in December 1740. Unable to resist, Chanda Sahib surrendered the fort to Raghuji on 14 March 1741. Chanda Saheb and his son were arrested and sent to Nagpur.[66] Rajputana also came under Maratha attacks during this time.[67] In June 1756 Luís Mascarenhas, Count of Alva (Conde de Alva), the Portuguese Viceroy was killed in action by the Maratha Army in Goa.

After the successful campaign of Karnataka and the Trichinopolly, Raghuji returned from Karnataka. He undertook six expeditions into Bengal from 1741 to 1748.[68][page needed] The resurgent Maratha Confederacy launched brutal raids against the prosperous Bengali state in the 18th century, which further added to the decline of the Nawabs of Bengal. During their invasions and occupation of Bihar[69] and western Bengal up to the Hooghly River[70] and during their occupation of western Bengal, the Marathas perpetrated atrocities against the local population.[70] The Maratha atrocities were recorded by both Bengali and European sources, which reported that the Marathas demanded payments, and tortured or killed anyone who couldn't pay.[70]

Raghuji was able to annex Odisha to his kingdom permanently as he successfully exploited the chaotic conditions prevailing in Bengal after the death of its governor Murshid Quli Khan in 1727. Constantly harassed by the Bhonsles, Odisha, Bengal and parts of Bihar were economically ruined. Alivardi Khan, the Nawab of Bengal made peace with Raghuji in 1751 ceding Cuttack (Odisha) up to the river Subarnarekha, and agreeing to pay Rs. 1.2 million annually as the Chauth for Bengal and Bihar.[67]

The city of Delhi was sacked ten times by Marathas between 1737 and 1788. During this period, Maratha soldiers raped thousands of women including 350 Mughal queens and princesses.[71] In May 1754, Malhar Rao Holkar with his 20,000 Maratha soldiers raided the camp of Emperor Ahmad Shah at Sikandarabad, they proceeded to loot the camp and raped women in gangs including queens and princesses after emperor had fled.[71]

Balaji Bajirao encouraged agriculture, protected the villagers and brought about a marked improvement in the state of the territory. Raghunath Rao, brother of Nanasaheb, pushed into the wake of the Afghan withdrawal after Ahmed Shah Abdali's plunder of Delhi in 1756. Delhi was captured by the Maratha army under Raghunath Rao in August 1757, defeating the Afghan garrison in the Battle of Delhi. This laid the foundation for the Maratha conquest of North-west India. In Lahore, as in Delhi, the Marathas were now major players.[72] After the 1758 Battle of Attock, the Marathas captured Peshawar defeating the Afghan troops in the Battle of Peshawar on 8 May 1758.[35]

Just prior to the battle of Panipat in 1761, the Marathas looted "Diwan-i-Khas" or Hall of Private Audiences in the Red Fort of Delhi, which was the place where the Mughal emperors used to receive courtiers and state guests, in one of their expeditions to Delhi.

The Marathas who were hard pressed for money stripped the ceiling of Diwan-i-Khas of its silver and looted the shrines dedicated to Muslim maulanas.[73]

During the Maratha invasion of Rohilkhand in the 1750s

The Marathas defeated the Rohillas, forced them to seek shelter in hills and ransacked their country in such a manner that the Rohillas dreaded the Marathas and hated them ever afterwards.[73]

In 1760, the Marathas under Sadashivrao Bhau responded to the news of the Afghans' return to North India by sending a large army north. Bhau's force was bolstered by some Maratha forces under Holkar, Scindia, Gaekwad and Govind Pant Bundele with Suraj Mal. The combined army of over 50,000 regular troops re-captured the former Mughal capital, Delhi, from an Afghan garrison in August 1760.[74]

Delhi had been reduced to ashes many times due to previous invasions, and there was an acute shortage of supplies in the Maratha camp. Bhau ordered the sacking of the already depopulated city.[73][75] He is said to have planned to place his nephew and the Peshwa's son, Vishwasrao, on the Mughal throne. By 1760, with the defeat of the Nizam in the Deccan, Maratha power had reached its zenith with a territory of over 2,500,000 square kilometres (970,000 sq mi).[7]

Ahmad Shah Durrani called on the Rohillas and the Nawab of Oudh to assist him in driving out the Marathas from Delhi.[citation needed] Huge armies of Muslim forces and Marathas collided with each other on 14 January 1761 in the Third Battle of Panipat. The Maratha Army lost the battle, which halted their imperial expansion. The Jats and Rajputs did not support the Marathas. Historians have criticised the Maratha treatment of fellow Hindu groups. Kaushik Roy says, "The treatment by the Marathas of their co-religionist fellows – Jats and Rajputs was definitely unfair and ultimately had to pay its price in Panipat where Muslim forces had united in the name of religion."[72]

The Marathas had antagonised the Jats and Rajputs by taxing them heavily, punishing them after defeating the Mughals and interfering in their internal affairs.[citation needed] The Marathas were abandoned by Raja Suraj Mal of Bharatpur, who quit the Maratha alliance at Agra before the start of the great battle and withdrew their troops as Maratha general Sadashivrao Bhau did not heed the advice to leave soldiers' families (women and children) and pilgrims at Agra and not take them to the battlefield with the soldiers, rejected their co-operation. Their supply chains (earlier assured by Raja Suraj Mal) did not exist.[citation needed]

Peshwa Madhavrao I was the fourth Peshwa of the Maratha Confederacy. He worked as a unifying force in the Confederacy and moved to the south to subdue Mysore and the Nizam of Hyderabad to assert Maratha power. He sent generals such as Bhonsle, Scindia and Holkar to the north, where they re-established Maratha authority by the early 1770s.[citation needed] Madhav Rao I crossed the Krishna River in 1767 and defeated Hyder Ali in the battles of Sira and Madgiri. He also rescued the last queen of the Keladi Nayaka Kingdom, who had been kept in confinement by Hyder Ali in the fort of Madgiri.[76]

In early 1771, ten years after the collapse of Maratha authority over North India following the Third Battle of Panipat, Mahadaji Shinde recaptured Delhi and installed Shah Alam II as a puppet ruler on the Mughal throne[77] receiving in return the title of deputy Vakil-ul-Mutlak or vice-regent of the Empire and that of Vakil-ul-Mutlak being at his request conferred on the Peshwa. The Mughals also gave him the title of Amir-ul-Amara (head of the amirs).[78] After taking control of Delhi, the Marathas sent a large army in 1772 to punish Afghan Rohillas for their involvement in Panipat. Their army devastated Rohilkhand by looting and plundering as well as taking members of the royal family as captives.[77]

The Marathas invaded Rohilkhand to avenge the Rohillas' atrocities in the Panipat war. The Marathas under the leadership of Mahadaji Shinde entered the land of Sardar Najib-ud-Daula which was held by his son Zabita Khan after his death. Zabita Khan initially resisted the attack with Sayyid Khan and Saadat Khan behaving with gallantry, but was eventually defeated with the death of Saadat Khan by the Marathas and was forced to flee to the camp of Shuja-ud-Daula and his country was ravaged by Marathas.[79] Mahadaji Shinde captured the family of Zabita Khan, desecrated the grave of Najib ad-Dawlah and looted his fort.[80] With the fleeing of the Rohillas, the rest of the country was burnt, with the exception of the city of Amroha, which was defended by some thousands of Amrohi Sayyid tribes.[81] The Rohillas who could offer no resistance fled to the Terai whence the remaining Sardar Hafiz Rahmat Khan Barech sought assistance in an agreement formed with the Nawab of Oudh, Shuja-ud-Daula, by which the Rohillas agreed to pay four million rupees in return for military help against the Marathas. Hafiz Rehmat, abhorring unnecessary violence, unlike the outlook of his fellow Rohillas such as Ali Muhammad and Najib Khan, prided himself on his role as a political mediator and sought an alliance with Awadh to keep the Marathas out of Rohilkhand. He bound himself to pay on behalf of the Rohillas. However, after he refused to pay, Oudh attacked the Rohillas.[82]

Shah Alam II, the Mughal Emperor spent six years in the Allahabad fort and after the capture of Delhi in 1771 by the Marathas, left for his capital under their protection.[83] He was escorted to Delhi by Mahadaji Shinde and left Allahabad in May 1771. During their short stay, Marathas constructed two temples in Allahabad city, one of them being the famous Alopi Devi Mandir. After reaching Delhi in January 1772 and realising the Maratha intent of territorial encroachment, however, Shah Alam ordered his general Najaf Khan to drive them out. In retaliation, Tukoji Rao Holkar and Visaji Krushna Biniwale attacked Delhi and defeated Mughal forces in 1772. The Marathas were granted an imperial sanad for Kora and Allahabad. They turned their attention to Oudh to gain these two territories. Shuja was, however, unwilling to give them up and made appeals to the English and the Marathas did not fare well at the Battle of Ramghat.[84] The Maratha and British armies fought in Ram Ghat, but the sudden demise of the Peshwa and the civil war in Pune to choose the next Peshwa forced the Marathas to retreat.[85]

Madhavrao Peshwa's victory over the Nizam of Hyderabad and Hyder Ali of Mysore in southern India established Maratha dominance in the Deccan. On the other hand, Mahadaji's victory over Jats of Mathura, Rajputs of Rajasthan and Pashtun-Rohillas of Rohilkhand (Bareilly division and Moradabad division of present-day Uttar Pradesh) re-established the Marathas in northern India. With the Capture of Delhi in 1771 and the capture of Najibabad in 1772 and treaties with Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II as a restricted monarch to the throne under Maratha suzerainty, the resurrection of Maratha power in the North was complete.[86][87][88][77]

Madhav Rao died in 1772, at the age of 27. His death is considered to be a fatal blow to the Maratha Confederacy and from that time Maratha power started to move on a downward trajectory, less an empire than a confederacy.[citation needed]

Confederacy era

[edit]

In a bid to effectively manage the large empire, Madhavrao Peshwa gave semi-autonomy to the strongest of the aristocracy.[citation needed] After the death of Peshwa Madhavrao I, various chiefs and jagirdars became de facto rulers and regents for the infant Peshwa Madhavrao II.[citation needed] Under the leadership of Mahadaji Shinde, the ruler of the state of Gwalior in central India, the Marathas defeated the Jats, the Rohilla Afghans and took Delhi which remained under Maratha control for the next three decades.[86] His forces conquered modern day Haryana.[89] Shinde was instrumental in resurrecting Maratha power after the débâcle of the Third Battle of Panipat, and in this, he was assisted by Benoît de Boigne.[citation needed]

After the growth in power of feudal lords like the Malwa sardars, the landlords of Bundelkhand and the Rajput kingdoms of Rajasthan who refused to pay tribute to him, he sent his army to conquer states such as Bhopal, Datiya, Chanderi, Narwar, Salbai and Gohad. However, he launched an unsuccessful expedition against the Raja of Jaipur but withdrew after the inconclusive Battle of Lalsot in 1787.[90] The Battle of Gajendragad was fought between the Marathas under the command of Tukojirao Holkar (the adopted son of Malharrao Holkar) and Tipu Sultan from March 1786 to March 1787 in which Tipu Sultan was defeated by the Marathas. By the victory in this battle, the border of the Maratha territory was extended to the Tungabhadra river.[91] The strong fort of Gwalior was then in the hands of Chhatar Singh, the Jat ruler of Gohad. In 1783, Mahadaji besieged the fort of Gwalior and conquered it. He delegated the administration of Gwalior to Khanderao Hari Bhalerao. After celebrating the conquest of Gwalior, Mahadaji Shinde turned his attention to Delhi again.[92]

The Maratha-Sikh treaty in 1785 made the small Cis-Sutlej states an autonomous protectorate of the Scindia Dynasty of the Maratha Confederacy,[93] as Mahadaji Shinde was deputed the Naib Vakil-i-Mutlaq (Deputy Regent of the empire) of Mughal affairs in 1784.[94][95] Following the Second Anglo-Maratha War in 1806, Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington drafted a treaty granting independence to the Sikh clans east of the Sutlej River in exchange for their allegiance to the British General Gerard Lake acting on his dispatch.[96][97] At the conclusion of the war, the frontier of British India was extended to the Yamuna.

Mahadaji Shinde had conquered Rania, Fatehabad and Sirsa from the governor of Hissar. Haryana then came under the Marathas. He divided Haryana into four territories: Delhi (Mughal emperor Shah Alam II, his family and areas surrounding Delhi), Panipat (Karnal, Sonepat, Kurukshetra and Ambala), Hisar (Hisar, Sirsa, Fatehabad, parts of Rohtak), Ahirwal (Gurugram, Rewari, Narnaul, Mahendragarh) and Mewat. Daulat Rao Scindia ceded Haryana on 30 December 1803 under the Treaty of Surji-Anjangaon to the British East India Company leading to the Company rule in India.

In 1788, Mahadaji's armies defeated Ismail Beg, a Mughal noble who resisted the Marathas.[98] The Rohilla chief Ghulam Kadir, Ismail Beg's ally, took over Delhi, capital of the Mughal dynasty and deposed and blinded the king Shah Alam II, placing a puppet on the Delhi throne. Mahadaji intervened and killed him, taking possession of Delhi on 2 October restoring Shah Alam II to the throne and acting as his protector.[99] Jaipur and Jodhpur, the two most powerful Rajput states, were still out of direct Maratha domination, so Mahadaji sent his general Benoît de Boigne to crush the forces of Jaipur and Jodhpur at the Battle of Patan.[100] Another achievement of the Marathas was their victories over the Nizam of Hyderabad's armies.[101][102]The last of these took place at the Battle of Kharda in 1795 with all the major Maratha powers jointly fighting Nizam's forces.[103]

Maratha–Mysore Wars

[edit]The Marathas came into conflict with Tipu Sultan and his Kingdom of Mysore, leading to the Maratha–Mysore War in 1785. The war ended in 1787 with Tipu Sultan being defeated by the Marathas.[104] The Maratha-Mysore war ended in April 1787 following the finalizing of the treaty of Gajendragad, as per which the Tipu Sultan of Mysore was obligated to pay 4.8 million rupees as a war cost to the Marathas and an annual tribute of 1.2 million rupees, in addition to returning all the territory captured by Hyder Ali.[105][106] In 1791–92, large areas of the Maratha Confederacy suffered a massive population loss due to the Doji bara famine.[107]

In 1791, irregulars like lamaans, pindaris and purbias not Marathas raided and looted the temple of Sringeri Shankaracharya, killing and wounding many people, including Brahmins, plundering the monastery of all its valuable possessions, and desecrating the temple by displacing the image of goddess Sāradā.[citation needed] [108]

The Maratha Confederacy soon allied with the British East India Company (based in the Bengal Presidency) against Mysore in the Anglo-Mysore Wars. After the British had suffered a defeat against Mysore in the first two Anglo-Mysore Wars, the Maratha cavalry assisted the British in the last two Anglo-Mysore Wars from 1790 onwards, eventually helping the British conquer Mysore in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War in 1799.[109] After the British conquest, however, the Marathas launched frequent raids in Mysore to plunder the region, which they justified as compensation for past losses to Tipu Sultan.[110]

British intervention

[edit]

In 1775, the British East India Company, from its base in Bombay, intervened in a succession struggle in Pune, on behalf of Raghunathrao (also called Raghobadada), who wanted to become Peshwa of the confederacy. The British also wanted to nip in the bud any potential anti-British, French-Maratha alliance.[111] Maratha forces under Tukojirao Holkar and Mahadaji Shinde defeated a British expeditionary force at the Battle of Wadgaon, but the heavy surrender terms, which included the return of annexed territory and a share of revenues, were disavowed by the British authorities at Bengal and fighting continued. What became known as the First Anglo-Maratha War ended in 1782 with a restoration of the pre-war status quo and the East India Company's abandonment of Raghunathrao's cause.[112]

In 1799, Yashwantrao Holkar was crowned King of the Holkars and he captured Ujjain. He started campaigning towards the north to expand his dominion in that region. Yashwant Rao rebelled against the policies of Peshwa Baji Rao II. In May 1802, he marched towards Pune the seat of the Peshwa. This gave rise to the Battle of Poona in which the Peshwa was defeated. After the Battle of Poona, the flight of the Peshwa left the government of the Maratha state in the hands of Yashwantrao Holkar.[113] He appointed Amrutrao as the Peshwa and went to Indore on 13 March 1803. All except Gaekwad, chief of Baroda, who had already accepted British protection by a separate treaty on 26 July 1802, supported the new regime. He made a treaty with the British. Also, Yashwant Rao successfully resolved the disputes with Scindia and the Peshwa. He tried to unite the Maratha Confederacy but to no avail. In 1802, the British intervened in Baroda to support the heir to the throne against rival claimants and they signed a treaty with the new Maharaja recognising his independence from the Maratha Confederacy in return for his acknowledgement of British paramountcy. Before the Second Anglo-Maratha War (1803–1805), the Peshwa Baji Rao II signed a similar treaty. The defeat in the Battle of Delhi, 1803 during the Second Anglo-Maratha War resulted in the loss of influence over Delhi for the Marathas.[114]

The Second Anglo-Maratha War represents the military high-water mark of the Marathas who posed the last serious opposition to the formation of the British Raj. The real contest for India was never a single decisive battle for the subcontinent, rather, it turned on a complex social and political struggle for the control of the South Asian military economy. The victory in 1803 hinged as much on finance, diplomacy, politics and intelligence as it did on battlefield manoeuvring and war itself.[110]

Ultimately, the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1818) resulted in the loss of Maratha independence. It left the British in control of most of the Indian subcontinent. The Peshwa was exiled to Bithoor (Marat, near Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh) as a pensioner of the British. The Maratha heartland of Desh, including Pune, came under direct British rule, except the states of Kolhapur and Satara, which retained local Maratha rulers (descendants of Shivaji and Sambhaji II ruled over Kolhapur). The Maratha-ruled states of Gwalior, Indore, and Nagpur all lost territory and came under subordinate alliances with the British Raj as princely states that retained internal sovereignty under British paramountcy. Other small princely states of Maratha knights were retained under the British Raj as well.[citation needed]

The Third Anglo-Maratha War was fought by Maratha warlords separately instead of forming a common front and they surrendered one by one. Shinde and the Pashtun Amir Khan were subdued by the use of diplomacy and pressure, which resulted in the Treaty of Gwalior[115] on 5 November 1817.[citation needed] All other Maratha chiefs like Holkars, Bhonsles and the Peshwa gave up arms by 1818. British historian Percival Spear describes 1818 as a watershed year in the history of India, saying that by that year "the British dominion in India became the British dominion of India".[116][117]

The war left the British, under the auspices of the British East India Company, in control of virtually all of present-day India south of the Sutlej River. The famed Nassak Diamond was looted by the company as part of the spoils of the war.[118] The British acquired large chunks of territory from the Maratha Empire and in effect put an end to their most dynamic opposition.[119] The terms of surrender Major-general John Malcolm offered to the Peshwa were controversial amongst the British for being too liberal: The Peshwa was offered a luxurious life near Kanpur and given a pension of about 80,000 pounds.[citation needed]

Geography

[edit]The Maratha Confederacy, at its peak, encompassed a large area of the Indian sub-continent. At its zenith, it expanded from Punjab in the north to Hyderabad in the south, Kutch in the west to Oudh in the east. It bordered Oudh and Rajputana in the north. Apart from capturing various regions, the Marathas maintained a large number of tributaries who were bound by agreements to pay a certain amount of regular tax, known as Chauth. The confederacy collected defeated the Sultanate of Mysore under Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan, the Nawab of Oudh, the Nizam of Hyderabad, the Nawab of Bengal, Nawab of Sindh and the Nawab of Arcot as well as the Polygar kingdoms of South India. They extracted chauth from the rulers in Delhi, Oudh, Bengal, Bihar, Odisha and Rajputana.[120][121] They built up the large empire in India.[citation needed]

The Marathas were requested by Safdarjung, the Nawab of Oudh, in 1752 to help him defeat the Afghani Rohillas. The Maratha force set out from Pune and defeated the Afghan Rohillas in 1752, capturing the whole of Rohilkhand (Bareilly division and Moradabad division of present-day Uttar Pradesh).[73] In 1752, the Marathas entered into an agreement with the Mughal emperor, through his wazir, Safdarjung, and the Mughals gave the Marathas the chauth of Doab in addition to the Subahdari of Ajmer and Agra.[122] In 1758, Marathas started their north-west conquest and expanded their boundary till Afghanistan. They defeated the Afghan forces of Ahmed Shah Abdali. The Afghans numbered around 25,000–30,000 and were led by Timur Shah, the son of Ahmad Shah Durrani.[123]

During the confederacy era, Mahadaji Shinde resurrected the Maratha domination over much of Northern India which was lost after the Third Battle of Panipat. Delhi and much of Uttar Pradesh were under the suzerainty of the Scindhias of the Maratha Confederacy, but following the Second Anglo-Maratha War of 1803–1805, the Marathas lost these territories to the British East India Company.[78][95]

Territorial evolution

[edit]| Year | Expanse | Background |

|---|---|---|

| 1680 |

|

Except for the Portuguese possessions of Goa, Chaul, Salsette, and Bassein, the Abyssinian pirate stronghold of Janjira, and the English settlement on Bombay Island, Sivaji had complete control over the entire Konkan region from Daman in the north to Karwar in the south at the time of his death in 1680. His eastern boundary extended through the districts of Nasik and Poona, encompassing the entire Satara region and most of Kolhapur. Additionally, he held territories in Bellary, Kopal, Sira, Bangalore, Kolar, Vellore, Arni, and Gingi, along with a share in his brother's principality of Tanjore.[124] |

| 1700 |

|

Sambhaji, who succeeded Shivaji, was captured and subsequently executed by Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb in 1689. However, by the beginning of the 18th century, the Marathas had managed to regain their power.[124] |

| 1785 |

|

After Aurangzeb, Marathas conquered a significant portion of India, stretching from the Chenab River to the borders of Bengal.[125]

The involvement of the Bombay Government in advocating Raghoba's claim to the Peshwaship of the Maratha Confederacy resulted in the First Anglo-Maratha War, ultimately concluding with the signing of the Treaty of Salbai (1782).[126] |

| 1798 |

|

In 1795, the Marathas overwhelmed the Nizam of Hyderabad at Kharda. The Maratha frontier was expanded all the way to the Tungabhadra River.[127] |

| 1805 |

|

The Treaty of Bassein (1802) resulted in a conflict with the Marathas. As per the treaty, the Peshwa, Baji Rao II, was reinstated in Poona as a mere figurehead under the control of the British East India Company. In exchange, he agreed to allow the British to station a subsidiary force in his territory and accepted British arbitration in any disputes with other regional powers. This agreement made a war with the Marathas unavoidable. In the ensuing Second Anglo-Maratha War, the Treaty of Deogaon saw Berar surrender the province of Cuttack, including Balasore, which connected Bengal with Madras. Additionally, the Treaty of Surji Arjangaon led to Scindia relinquishing the Upper Doab, his forts and territories northeast of the Rajput States, the districts of Broach and Ahmadnagar, as well as his possessions south of the Ajanta hills. Asirgarh, Burhanpur, and certain districts in the Tapti Valley were returned to Scindia. The Peshwa received the fort and district of Ahmadnagar, while the Nizam acquired the district south of the Ajanta hills. Furthermore, the western part of Berar, lying west of the Wardha River and south of the fortress of Gawilgarh, was also granted to the Nizam.[128] |

| 1836 |

|

During the final and Third Anglo-Maratha war (1817–19), the British achieved widespread success in their military endeavours. They successfully removed the Peshwa from power, confiscated his territories, and compelled him to reside in Bithur near Cawnpore. The Raja of Satara was permitted to retain a small portion of his ancestral domains until it eventually came under British control during the time of Dalhousie. The independence of Scindia, Holkar, and Berar was completely dismantled, leading to significant territorial reductions for these states. Holkar was compelled to relinquish Ajmer, which held strategic importance in Rajputana. The pirate leaders of the Konkan were coerced into surrendering their coastal holdings. Treaties were established with significant Rajput States such as Jaipur, Jodhpur, and Mewar, as well as with smaller Rajput States like Banswara, Dungarpur, Partabgarh, Jaisalmer, and Kotah. Additionally, British protection was extended to Bhopal, the States of Bundelkhand, Malwa, and Kathiawar.[129] |

| 1856 |

|

The British territory expanded by incorporating the following States under Dalhousie's rule, following the doctrine of lapse: Satara (1848), Jaitpur (1849) situated northeast of Jhansi, Sambalpur (1849), Jhansi (1853), and Nagpur (1854).[130] |

Government and military

[edit]Administration

[edit]

The Ashtapradhan (The Council of Eight) was a council of eight ministers that administered the Maratha Kingdom. This system was formed by Shivaji.[131] Ministerial designations were drawn from the Sanskrit language and comprised:

- Peshwa or Pantpradhan – Prime Minister, general administration of the Empire

- Amatya or Mazumdar – Finance Minister, managing accounts of the Empire[132][unreliable source?]

- Sachiv – Secretary, preparing royal edicts

- Mantri – Interior Minister, managing internal affairs especially intelligence and espionage

- Senapati – Commander-in-Chief, managing the forces and defense of the Empire

- Sumant – Foreign Minister, to manage relationships with other sovereigns

- Nyayadhyaksh – Chief Justice, dispensing justice on civil and criminal matters

- Panditrao – High Priest, managing internal religious matters

- Chitnis – Personal Secretary and senior writer of the Chhatrapati. Sometimes considered second to the Peshwa in their absence, not in the Ashta Pradhan Mandal but equal to them.

With the notable exception of the priestly Panditrao and the judicial Nyayadisha, the other pradhans held full-time military commands and their deputies performed their civil duties in their stead. In the later era of the Maratha Confederacy, these deputies and their staff constituted the core of the Peshwa's bureaucracy.[citation needed]

The Peshwa was the titular equivalent of a modern Prime Minister. Shivaji created the Peshwa designation in order to more effectively delegate administrative duties during the growth of the Maratha Kingdom. Prior to 1749, the Peshwas held office for 8–9 years and controlled the Maratha Army. They later became the de facto hereditary administrators of the Maratha Empire from 1749 till its end in 1818.[citation needed]

Under the administration of the Peshwas and with the support of several key generals and diplomats (listed below), the Maratha Empire reached its zenith, ruling most of the Indian subcontinent. It was also under the Peshwas that the Maratha Empire came to its end through its formal annexation into the British Empire by the British East India Company in 1818.[citation needed]

Shivaji was an able administrator who established a government that included modern concepts such as cabinet, foreign policy and internal intelligence.[133] He established an effective civil and military administration. He believed that there was a close bond between the state and the citizens. He is remembered as a just and welfare-minded king. Cosme da Guarda says of him that:[101]

Such was the good treatment Shivaji accorded to people and such was the honesty with which he observed the capitulations that none looked upon him without a feeling of love and confidence. By his people he was exceedingly loved. Both in matters of reward and punishment he was so impartial that while he lived he made no exception for any person; no merit was left unrewarded, no offence went unpunished; and this he did with so much care and attention that he specially charged his governors to inform him in writing of the conduct of his soldiers, mentioning in particular those who had distinguished themselves, and he would at once order their promotion, either in rank or in pay, according to their merit. He was naturally loved by all men of valor and good conduct.

The Marathas carried out many sea raids, such as plundering Mughal Naval ships and European trading vessels. European traders described these attacks as piracy, but the Marathas viewed them as legitimate targets because they were trading with, and thus financially supporting, their Mughal and Bijapur enemies. After the representatives of various European powers signed agreements with Shivaji or his successors, the threat of plundering or raids against Europeans began to reduce.

Military

[edit]The Maratha Army under Shivaji was a national army consisting of personnel drawn mainly from his empire which corresponds to present-day Maharashtra. It was a homogeneous body commanded by a regular cadre of officers, who had to obey one supreme commander. With the rise of the Peshwas, however, this national army had to make room for a feudal force provided by different Maratha sardars.[134] This new Maratha Army was not homogeneous, but employed soldiers of different backgrounds, both locals and foreign mercenaries, including large numbers of Arabs, Sikhs, Rajputs, Sindhis, Rohillas, Abyssinians, Pashtuns, and Europeans. The army of Nana Fadnavis, for example, included 5,000 Arabs.[135] The army of Baji Rao II included the Pinto brothers Jose Antonio and Francisco from the famous Goan noble family who had escaped Goa after trying to overthrow the government in the Conspiracy of the Pintos.[136][137]

Some historians have credited the Maratha Navy for laying the foundation of the Indian Navy and bringing significant changes in naval warfare. A series of sea forts and battleships were built in the 17th century during the reign of Shivaji. It has been noted that vessels built in the dockyards of Konkan were mostly indigenous and constructed without foreign aid.[138] Further, in the 18th century, during the reign of Admiral Kanhoji Angre, a host of dockyard facilities were built along the entire western coastline of present-day Maharashtra. The Marathas fortified the entire coastline with sea fortresses with navigational facilities.[139] Nearly all the hill forts, which dot the landscape of present-day western Maharashtra were built by the Marathas. The renovation of Gingee Fort in Tamil Nadu, has been particularly applauded, according to the contemporary European accounts, the defence fortifications matched the European ones.[140]

The Marathas prioritized technical advancement over establishing a modern command structure, resulting in a trade-off. While they excelled as craftsmen and technicians, successfully replicating the latest foreign military technology, their ability to govern as nation-builders was hindered because they struggled to effectively manage the intricate workings of command and failed to address the shortcomings in their general staff system. The fragmented Maratha state was unable to unite due to political divisions, undoing the progress made through technology.[141][142]

Afghan accounts

[edit]

The Maratha Army, especially its infantry, was praised by almost all the enemies of the Maratha Empire, ranging from the Duke of Wellington to Ahmad Shah Abdali.[citation needed] After the Third Battle of Panipat, Abdali was relieved as the Maratha Army in the initial stages were almost in the position of destroying the Afghan armies and their Indian Allies, the Nawab of Oudh and Rohillas. The grand wazir of the Durrani Empire, Sardar Shah Wali Khan was shocked when Maratha commander-in-chief Sadashivrao Bhau launched a fierce assault on the centre of the Durrani Army, over 10,000 Durrani soldiers were killed alongside Haji Atai Khan, one of the chief commander of the Durrani Army and nephew of wazir Shah Wali Khan. Such was the fierce assault of the Maratha infantry in hand-to-hand combat that Afghan armies started to flee and the wazir in desperation and rage shouted, "Comrades whither do you fly, our country is far off".[143] Post battle, Ahmad Shah Abdali, in a letter to one Indian ruler claimed that Afghans were able to defeat the Marathas only because of the blessings of the almighty and that any other army would have been destroyed by the Maratha army on that particular day even though the Maratha Army was numerically inferior to the Durrani Army and its Indian allies.[144]

European accounts

[edit]

Similarly, Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, after defeating the Marathas, noted that the Marathas, though poorly led by their generals, had regular infantry and artillery that matched the level of that of the Europeans and warned other British officers from underestimating the Marathas on the battlefield. He cautioned one British general: "You must never allow Maratha infantry to attack head on or in close hand-to-hand combat as in that your army will cover itself with utter disgrace".[145][citation needed]

He summarised Maratha tactics as follows: the Mahrattas employ two methods in their operations. They primarily rely on their cavalry to disrupt the enemy's supplies, causing distress in their camp and forcing them to retreat. Once the retreat begins, the Mahrattas unleash their infantry and formidable artillery to relentlessly pursue the enemy. By depriving the opponent of provisions, they compel them to hasten their march, while remaining confident in their own safety from counterattacks. They trail the enemy with their cavalry during marches, and when the enemy halts, they encircle and assault them using their infantry and cannons, making escape nearly impossible. Under no circumstances should you allow the enemy to engage you with their infantry. The Mahrattas possess such powerful artillery that it would be impossible to maintain your camp against it. If you receive word of their approach when they are close and ready to attack, it would be advisable to secure your baggage in any way possible and initiate an attack against them. It is crucial to prevent them from launching an attack on your camp at all costs.[146]

Even when Wellesley became the Prime Minister of Britain, he held the Maratha infantry in utmost respect, claiming it to be one of the best in the world. However, at the same time, he noted the poor leadership of Maratha Generals, who were often responsible for their defeats.[145][citation needed]

Wellesley Charles Metcalfe, one of the ablest of the British Officials in India and later acting Governor-General, wrote in 1806:

India contains no more than two great powers, British and Mahratta, and every other state acknowledges the influence of one or the other. Every inch that we recede will be occupied by them.[147][148]

Norman Gash says that the Maratha infantry was equal to that of British infantry.[142] After the Third Anglo-Maratha war in 1818, Britain listed the Marathas as one of the martial races to serve in the British Indian Army. The 19th-century diplomat Sir Justin Sheil commented about the British East India Company copying the French Indian Army in raising an army of Indians:

It is to the military genius of the French that we are indebted for the formation of the Indian army. Our warlike neighbours were the first to introduce into India the system of drilling native troops and converting them into a regularly disciplined force. Their example was copied by us, and the result is what we now behold. The French carried to Persia the same military and administrative faculties, and established the origin of the present Persian regular army, as it is styled. When Napoleon the Great resolved to take Iran under his auspices, he dispatched several officers of superior intelligence to that country with the mission of General Gardanne in 1808. Those gentlemen commenced their operations in the provinces of Azerbaijan and Kermanshah, and it is said with considerable success.

— Sir Justin Sheil (1803–1871).[149]

Rulers, administrators and generals

[edit]Chhatrapati

[edit]- Shivaji I (1630–1680)

- Sambhaji I (1657–1689)

- Rajaram I (1670–1700)

Satara:

- Shahu I (r. 1708–1749) (alias Shivaji II, son of Sambhaji)

- Ramaraja II (Adopted, alleged grandson of Rajaram and Queen Tarabai) (r. 1749–1777)

- Shahu II (r. 1777–1808)

- Pratap Singh (r. 1808–1839) – signed a treaty with the East India Company ceding part of the sovereignty of his kingdom to the company[150]

Kolhapur:

- Tarabai (1675–1761) (wife of Rajaram) in the name of her son Shivaji II

- Shivaji II (1700–1714)

- Sambhaji II (1714–1760) – came to power by deposing his half-brother Shivaji II

- Shivaji III (1760–1812) (adopted from the family of Khanwilkar)

Peshwas

[edit]- Moropant Trimbak Pingle (1657–1683)

- Nilakanth Moreshvar Pingale (1683–1689)

- Ramchandra Pant Amatya (1689–1708)

- Bahiroji Pingale (1708–1711)

- Parshuram Trimbak Kulkarni (1711–1713)

Peshwas from the Bhat family

[edit]From Balaji Vishwanath onwards, the actual power gradually shifted to the Bhat family of Peshwas based in Poona.

- Balaji Vishwanath (1713–1720)

- Baji Rao I (1720–1740)

- Balaji Baji Rao (1740–1761)

- Madhava Rao I (1761–1772)

- Narayan Rao Baji Rao (1772 –1773)

- Raghunath Rao (1773 – 1774)

- Sawai Madhava Rao II Narayan (1774–1795)

- Baji Rao II (1796–1818)

- Nana Saheb (1851–1857)

Federal houses of Maratha Confederacy

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ (/məˈrɑːtə/ muh-RAH-ta;[9][10][11] Marathi pronunciation: [məˈɾaːʈʰaː])

- ^ The Peshwa between 1737 and 1761 and the Scindias between 1771 and 1803

- ^ "a formidable confederacy was formed by Maratha diplomats during the first Maratha war.........the Peshwa was made Vakil-i-mutlak and Mahadaji Scindhia deputy Vakil-i-mutlak and the real control of Delhi passed into the hands of Mahadaji Scindhia"[25]

- ^ Bajirao succeeded his father as the Peshwa. His sons, grandsons, and great-grandson succeeded him. They were Chitpavan Brahmins.[28]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Madan, T. N. (1988). Way of Life: King, Householder, Renouncer : Essays in Honour of Louis Dumont. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 360. ISBN 978-81-208-0527-9.

- ^ Chattopadhyaya, Sudhakar (1978). Reflections on the Tantras. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 75. ISBN 978-81-208-0691-7.

- ^ Hatalkar (1958).

- ^ "Maratha Aristocracy: The Scindias of Gwalior".

- ^ Kincaid & Parasnis, p.156

- ^ Haig L, t-Colonel Sir Wolseley (1967). The Cambridge History of India. Vol. 3 (III). Turks and Afghans. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University press. p. 394. ISBN 9781343884571. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- ^ a b Turchin, Adams & Hall (2006), p. 223.

- ^ Bang, Peter Fibiger; Bayly, C. A.; Scheidel, Walter (2020). The Oxford World History of Empire: Volume One: The Imperial Experience. Oxford University Press. pp. 92–94. ISBN 978-0-19-977311-4.

- ^ Upton, Clive; Kretzschmar, William A. (2017). The Routledge dictionary of pronunciation for current English (2nd ed.). London; New York: Routledge. p. 803. ISBN 978-1-138-12566-7.

- ^ Bollard, John K., ed. (1998). Pronouncing dictionary of proper names: pronunciations for more than 28,000 proper names, selected for currency, frequency, or difficulty of pronunciation (2nd ed.). Detroit, Mich: Omnigraphics. p. 633. ISBN 978-0-7808-0098-4.

- ^ Upton, Clive; Kretzschmar, William A.; Konopka, Rafal (2001). The Oxford dictionary of pronunciation for current English. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 622. ISBN 978-0-19-863156-9. OCLC 46433686.

- ^ O'Hanlon, Rosalind (2016), "Maratha Empire", The Encyclopedia of Empire, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–7, doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe357, ISBN 978-1-118-45507-4

- ^ Guha, Sumit (23 December 2019), "The Maratha Empire", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History, ISBN 978-0-19-027772-7

- ^ Vendell, Dominic (26 November 2021). "Transacting Politics in the Maratha Empire: An Agreement between Friends, 1795". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 64 (5–6): 826–863. doi:10.1163/15685209-12341554. hdl:10871/125607. ISSN 1568-5209.

The secretaries Sridhar Lakshman and Krishnarao Madhav managed the communications of the Maratha ruler at Nagpur, while their partner, the merchant-moneylender Baburao Viswanath Vaidya, was the envoy of the Pune-based Peshwa, a powerful Brahmin minister and leader of the allied states comprising the Maratha Empire.

- ^ Kumar, Ravinder (2013). Western India in the Nineteenth Century: A Study in the Social History of Maharashtra. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-03146-6.

Prominent among these chiefs were the Bhonsles who established themselves in Nagpur; the Scindhias who gained control of Gwalior; the Gaekwads who set themselves up in Baroda; and the Holkars who seized hold of Indore. Between the Peshwas and the Maratha chiefs there subsisted a relationship which it is most difficult to define. The chiefs were to all intents and purposes independent, yet they recognised the Peshwa as the head of the Maratha polity

- ^ Kantak (1993), p. 24.

- ^ Pagdi (1993), p. 98: Shivaji's coronation and setting himself up as a sovereign prince symbolises the rise of the Indian people in all parts of the country. It was a bid for Hindavi Swarajya (Indian rule), a term in use in Marathi sources of history.

- ^ a b Jackson (2005), p. 38.

- ^ Osborne, Eric W. (3 July 2020). "The Ulcer of the Mughal Empire: Mughals and Marathas, 1680–1707". Small Wars & Insurgencies. 31 (5): 988–1009. doi:10.1080/09592318.2020.1764711. ISSN 0959-2318. S2CID 221060782.

- ^ Clingingsmith, David; Williamson, Jeffrey G. (1 July 2008). "Deindustrialization in 18th and 19th century India: Mughal decline, climate shocks and British industrial ascent". Explorations in Economic History. 45 (3): 209–234. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2007.11.002. ISSN 0014-4983.

- ^ Kantak, M.R. (1978). "The Political Role of Different Hindu Castes and Communities in Maharashtra in the Foundation of the Shivaji's Swarajya". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 38 (1): 44. JSTOR 42931051.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra (1994). Anglo-Maratha Relations, 1785–96. Vol. 2. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7154-789-0.

While the distracted Maratha kingdom of Aurangzeb's later ycars was fighting for survival, none could foresee that the insignificant British settlements of Bombay, Madras and Calcutta would one day become the political and economic bases of a vast empire.

- ^ Garg, Sanjay (2022). The Raj and the Rajas : Money and Coinage in Colonial India. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-82889-4.

From the Mughal point of view, the hostilities between the Company Bahadur and the Marathas could appear as a troublesome contest for power between the Imperial Diwan of Bengal and the Vakil-i Mutlaq or Imperial Regent. The actual participants of course were considerably more cynical of the position of the Emperor, both the English and Scindia treating their suzerain lord with scant respect..The paramount position of the Mughal within the rituals of supreme and sovereign authority may be amply demonstrated by reference to the coins of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Following the doctrine of khutba and sikka, new claimants to hegemony could be expected to be revealed on the coins of different jurisdictions. Yet for much of India they are not to be found. Reference to the graph at the end of this paper will confirm that both the Marathas and the British coined in the name of the Mughal.

- ^ Mehta 2005: "Vishwanath consolidated the Maratha power in the Deccan and led an expeditionary force to Delhi (1718–19) as an ally of the Sayyad brothers. He made the Maratha presence felt at the metropolis for the first time, secured the release of Shahu's family members from Mughal captivity, and obtained the confirmation of the Mughal-Maratha Treaty of 1718 from the emperor. This treaty, by which Shahu accepted the nominal suzerainty of the Mughal Crown in return for his right to collect chauth and sardeshmukhi from all the six provinces of 'the Mughal Deccan'...Delhi became the hub of Maratha political and military activities with effect from 1752, and they used the Mughal emperor as a mere tool in their hands to wield the imperial powers in his name and under his nominal suzerainty."

- ^ Chaurasia (2004), p. X, preface.

- ^ Chaurasia (2004), p. 12.

- ^ Vincent A. Smith (1981). The Oxford History of India, Edited by Percival Spear. Oxford University Press. p. 492.

We have seen that the Marathas rather than the Persians or Afghans were the successors of the Mughuls as the holders of imperial power. The Persian attempt proved to be nothing more than a high-sounding raid while the Afghans of Ahmad Shah Abdali lacked the resources to sustain and the genius to exploit their victory. The Maratha succession proved to be an abortive one, but they controlled a larger part of India for a longer period than anyone else during the Anglo-Mughul interregnum

- ^ Gokhale, Sandhya (2008). The Chitpavans: Social Ascendancy of a Creative Minority in Maharashtra, 1818–1918. Shubhi Publications. p. 82. ISBN 978-81-8290-132-2.

- ^ Ghosh, D.K. Ed. A Comprehensive History Of India Vol. 9. pp. 512–523.

- ^ New Cambridge History of India. The Marathas – Cambridge History of India (Vol. 2, Part 4).

- ^ "Maratha confederacy | Maratha Empire, Peshwa, Shivaji | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 24 April 2025.

The effective control of the peshwas ended with the great defeat of Panipat (1761) at the hands of the Afghans and the death of the young peshwa Madhav Rao I in 1772. Thereafter the Maratha state was a confederacy of five chiefs under the nominal leadership of the peshwa at Poona (now Pune) in western India. Though they united on occasion, as against the British (1775–82), more often they quarreled.

- ^ Goswami, Arunansh (1 December 2023). "Maharaja's German: Anthony Pohlmann in India. | EBSCOhost". openurl.ebsco.com. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ "Rajas of Maratha Confederacy". Britannica History. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ Mehta (2005), p. 204.

- ^ a b Sen (2010), p. 16.

- ^ Ramusack (2004), p. 35.

- ^ Gordon, Stewart (1993). The Marathas 1600–1818. Cambridge University Press. pp. 178–195. ISBN 978-0-521-26883-7.

- ^ Kulkarni, A.R. (2008). "Military Organization of the Marathas". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 69: 417–425.

- ^ Wink, André (1986). Land and Sovereignty in India: Agrarian Society and Politics under the Eighteenth-century Maratha Svarajya. Cambridge University Press. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0-521-05180-4.

- ^ Hunter, William Wilson (1908). A Brief History of the Indian Peoples. p. 149,159,160,197.

- ^ Keene, Henry George (1895). Madhava Rao Sindhia and the Hindu Reconquest of India. p. 11.

- ^ Jones (1974), p. 25.

- ^ Gokhale (1988), p. 112.

- ^ a b Pearson (1976), pp. 221–235.

- ^ Vartak (1999), pp. 1126–1134.

- ^ Kantak (1993), p. 18.

- ^ Mehta (2005), p. 707: quote: It explains the rise to power of his Peshwa (prime minister) Balaji Vishwanath (1713–20) and the transformation of the Maratha Kingdom into a vast realm, by the collective action of all the Maratha stalwarts.

- ^ Richards (1995), p. 12.

- ^ Mehta (2005).

- ^ Mehta (2005), p. 50.

- ^ Richards (1995), p. 223.

- ^ Mehta (2005), pp. 53, 706.

- ^ a b Sen (2010), p. 11.

- ^ Mehta (2005), p. 81.

- ^ Mehta (2005), pp. 101–103.

- ^ Mehta (2005), pp. 39.

- ^ a b Sen (2010), p. 12.

- ^ Agrawal (1983), pp. 24, 200–202.

- ^ Mehta (2005), pp. 492–494.

- ^ Montgomery (1972), p. 132.

- ^ Mehta (2005), p. 117.

- ^ Sen (2006), p. 12.

- ^ a b Sen (2006).

- ^ Sen (2010), p. 23.

- ^ Sen (2010), p. 13.

- ^ Mehta (2005), p. 202.

- ^ a b Sen (2010), p. 15.

- ^ Sarkar (1991).

- ^ Chaudhuri (2006), p. 253.

- ^ a b c Marshall (2006), p. 72.

- ^ a b Gupta, Hari Ram (1999). "Role of the Sikhs in Delhi as Compared with Others". History of the Sikhs: Sikh domination of the Mughal Empire, 1764-1803. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. pp. 353, 364. ISBN 978-81-215-0213-9.

- ^ a b Roy (2004), pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b c d Agrawal (1983), p. 26.

- ^ Mehta (2005), p. 140.

- ^ Mehta (2005), p. 274.

- ^ Mehta (2005), p. 458.

- ^ a b c Rathod (1994), p. 8.

- ^ a b Farooqui (2011), p. 334.

- ^ Edwin Thomas Atkinson (1875). Statistical, Descriptive and Historical Account of the North-western Provinces of India: Meerut division. 1875–76. Printed at the North-western Provinces' Government Press. p. 88.

- ^ The Great Maratha Mahadji Scindia by N.G. Rathod, pp. 8–9[ISBN missing]

- ^ Poonam Sagar (1993). Maratha Policy Towards Northern India. Meenakshi Prakashan. p. 158.

- ^ Jos J.L. Gommans (1995). The Rise of the Indo-Afghan Empire: c. 1710–1780. Brill. p. 178.

- ^ A.C. Banerjee; D.K. Ghose, eds. (1978). A Comprehensive History of India: Volume Nine (1712–1772). Indian History Congress, Orient Longman. pp. 60–61.

- ^ Sailendra Nath Sen (1998). Anglo-Maratha relations during the administration of Warren Hastings 1772–1785. Vol. 1. Popular Prakashan. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9788171545780.

- ^ Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (1947). History of Modern India: 1707 A.D. up to 2000 A.D.

- ^ a b Stewart (1993), p. 158.

- ^ Mahrattas, Sikhs and Southern Sultans of India: Their Fight Against Foreign (2001)

- ^ Kadiyan, Chand Singh (26 June 2019). "Panipat in History: A Study of Inscriptions". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 64: 403–419. JSTOR 44145479.

- ^ Mittal (1986), p. 13.

- ^ Rathod (1994), p. 95.

- ^ Sampath (2008), p. 238.

- ^ Rathod (1994), p. 30.

- ^ Sen (2010), p. 83: "By Mahadji Shinde's treaty of 1785 with the Sikhs, Maratha influence had been established over the divided Cis-Sutlej states. But at the end of the second Maratha war in 1806 that influence had been pass over to the British."

- ^ Ahmed, Farooqui Salma (2011). A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: From Twelfth to the Mid ... – Farooqui Salma Ahmed, Salma Ahmed Farooqui. Pearson Education India. ISBN 9788131732021. Retrieved 21 July 2012 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Chaurasia (2004), p. 13.

- ^ Wellesley, Arthur (1837). The Despatches, Minutes, and Correspondance, of the Marquess Wellesley, K.G. During His Administration in India. pp. 264–267.

- ^ Wellesley, Arthur (1859). Supplementary Despatches and Memoranda of Field Marshal Arthur, Duke of Wellington, K.G.: India, 1797–1805. Vol. I. pp. 269–279, 319.

"ART VI Scindiah to renounce all claims the Seik chiefs or territories" (p. 318)

- ^ Rathod (1994), p. 106.

- ^ Kulakarṇī (1996).

- ^ Sarkar (1994).

- ^ a b Majumdar (1951b).

- ^ Barua (2005), p. 91.

- ^ Stewart Gordon (1993). The Marathas – Cambridge History of India (Vol. 2, Part 4). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 169–171. ISBN 9781139055666.

- ^ Hasan (2005), pp. 105–107.

- ^ Naravane (2006), p. 175.

- ^ Anglo-Maratha relations, 1785–96

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III 1907, p. 502

- ^ Sen, Surendranath (1928). Military System of the Marathas: With a Brief Account of Their Maritime Activities. Book Company Limited, 1928. p. 159.

This picture may or may not have been overdrawn, but it should be remembered that the offenders were the Pendharis and the Purvias, and not Marathas.

- ^ Cooper (2003).

- ^ a b Cooper (2003), p. 69.

- ^ Kadam, Umesh Ashok (2016). "The Maratha Court and the Embassies of Saint-Lubin and M. Montigny: A Truce towards Cordial Relations". In Malekandathil, Pius (ed.). The Indian Ocean in the Making of Early Modern India. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315276809. ISBN 978-1-315-27680-9. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "Battle of Wadgaon, Encyclopædia Britannica". Archived from the original on 23 June 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ Charles Augustus Kincaid, Dattātraya Baḷavanta Pārasanīsa (1925). A History of the Maratha People: From the death of Shahu to the end of the Chitpavan epic (reprint ed.). S. Chand, 1925. p. 194.

- ^ Capper (1997), p. 28.

- ^ Prakash (2002), p. 300.

- ^ Nayar (2008), p. 64.

- ^ Trivedi & Allen (2000), p. 30.

- ^ United States Court of Customs and Patent Appeals (1930), p. 121.

- ^ Black (2006), p. 77.

- ^ Lindsay (1967), p. 556.

- ^ Saini & Chand (n.d.), p. 97.

- ^ Sen (2006), p. 13.

- ^ Roy (2011), p. 103.

- ^ a b Davies, Cuthbert Collin (1959). An Historical Atlas of the Indian Peninsula. Oxford University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-19-635139-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Davies, Cuthbert Collin (1959). An Historical Atlas of the Indian Peninsula. Oxford University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-19-635139-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Davies, Cuthbert Collin (1959). An Historical Atlas of the Indian Peninsula. Oxford University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-19-635139-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Davies, Cuthbert Collin (1959). An Historical Atlas of the Indian Peninsula. Oxford University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-19-635139-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Davies, Cuthbert Collin (1959). An Historical Atlas of the Indian Peninsula. Oxford University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-19-635139-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Davies, Cuthbert Collin (1959). An Historical Atlas of the Indian Peninsula. Oxford University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-19-635139-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Davies, Cuthbert Collin (1959). An Historical Atlas of the Indian Peninsula. Oxford University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-19-635139-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Sardesai (2002).

- ^ "Introduction to Rise of the Maratha". Krishna Kanta Handiqui State Open University. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ Singh (1998), p. 93.

- ^ Kar (1980), p. [page needed].

- ^ Majumdar (1951b), p. 512.

- ^ "Noted Goans during Peshwe era in Pune-3: 2 Goans follow illustrious kin".

- ^ "Goan colonel decorated in the Maratha army".

- ^ Bhave (2000), p. 28.

- ^ Sridharan (2000), p. 43.

- ^ Kantak (1993), p. 10.

- ^ Cooper, Randolf G.S. (1989). "Wellington and the Marathas in 1803". The International History Review. 11 (1). Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: 38. doi:10.1080/07075332.1989.9640499. ISSN 0707-5332. JSTOR 40105953. S2CID 153841517. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ a b Gash, Norman (1990). Wellington. Manchester University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7190-2974-5.

- ^ Sarkar (1950), p. 245.

- ^ Singh (2011), p. 213.

- ^ a b Lee (2011), p. 85.

- ^ Cooper, Randolf G.S. (1989). "Wellington and the Marathas in 1803". The International History Review. 11 (1). Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: 34. doi:10.1080/07075332.1989.9640499. ISSN 0707-5332. JSTOR 40105953. S2CID 153841517. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ Metcalfe (1855).

- ^ Nehru (1946).

- ^ Sheil & Sheil (1856).

- ^ Kulkarni (1995), p. 21.

Bibliography

[edit]- Agrawal, Ashvini (1983). Studies in Mughal History. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-2326-5.

- Barua, Pradeep (2005). The State at War in South Asia. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1344-1.

- Bhave, Y. G. (2000). From the Death of Shivaji to the Death of Aurangzeb: The Critical Years. Northern Book Centre. ISBN 978-81-7211-100-7.

- Black, Jeremy (2006). A Military History of Britain: from 1775 to the Present. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-99039-8.

- Capper, John (1997). Delhi, the Capital of India. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-1282-2.

- Chaurasia, R.S. (2004). History of the Marathas. New Delhi: Atlantic. ISBN 978-81-269-0394-8.

- Chaudhuri, Kirti N. (2006). The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company: 1660–1760. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-03159-2.

- Cooper, Randolf G.S. (2003). The Anglo-Maratha Campaigns and the Contest for India: The Struggle for Control of the South Asian Military Economy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82444-6.

- Farooqui, Salma Ahmed (2011). A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: Twelfth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-3202-1.

- Gokhale, Balkrishna Govind (1988). Poona in the eighteenth century: an urban history. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-562137-2.

- Hasan, Mohibbul (2005). History of Tipu Sultan. Delhi: Aakar Books. ISBN 978-81-87879-57-2.

- Hatalkar, V.G. (1958). Relations Between the French and the Marathas: 1668–1815. T.V. Chidambaran.

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III (1907), The Indian Empire, Economic (Chapter X: Famine, pp. 475–502), Published under the authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press. Pp. xxx, 1 map, 552.

- Jackson, William Joseph (2005). Vijayanagara voices: exploring South Indian history and Hindu literature. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7546-3950-3.

- Jones, Rodney W. (1974). Urban Politics in India: Area, Power, and Policy in a Penetrated System. University of California Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-520-02545-5.

- Kantak, M. R. (1993). The First Anglo-Maratha War, 1774–1783: A Military Study of Major Battles. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7154-696-1.

- Kar, H. C. (1980). Military history of India. Calcutta: Firma KLM. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- Kulakarṇī, A. Rā (1996). Marathas and the Marathas Country: The Marathas. Books & Books. ISBN 978-81-85016-50-4.

- Kulkarni, Sumitra (1995). The Satara Raj, 1818–1848: A Study in History, Administration, and Culture. Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-81-7099-581-4.

- Lee, Wayne (2011). Empires and Indigenes: Intercultural Alliance, Imperial Expansion, and Warfare in the Early Modern World. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-6527-2.

- Lindsay, J.O., ed. (1967). The New Cambridge Modern History. Vol. VII The Old Regime 1713–63. Cambridge: University Press.

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1951b). The History and Culture of the Indian People. Vol. 8 The Maratha Supremacy. Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan Educational Trust.

- Marshall, P. J. (2006). Bengal: The British Bridgehead: Eastern India 1740–1828. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02822-6.

- Metcalfe, Charles Theophilus (1855). Kaye, John William (ed.). Selections from the Papers of Lord Metcalfe: Late Governor-General of India, Governor of Jamaica, and Governor-General of Canada. London: Smith, Elder and Co.

- Mehta, Jaswant Lal (2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India 1707–1813. Sterling. ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6.

- Mittal, Satish Chandra (1986). Haryana: A Historical Perspective. New Delhi: Atlantic.

- Montgomery, Bernard Law (1972). A Concise History of Warfare. Collins. ISBN 9780001921498.

- Naravane, M.S. (2006). Battles of the Honourable East India Company: Making of the Raj. New Delhi: APH Publishing. ISBN 978-81-313-0034-3.

- Nayar, Pramod K. (2008). English Writing and India, 1600–1920: Colonizing Aesthetics. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-13150-1.

- Nehru, Jawaharlal (1946). Discovery of India. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Pagdi, Setumadhavarao S. (1993). Shivaji. National Book Trust. p. 21. ISBN 81-237-0647-2.

- Pearson, M.N. (February 1976). "Shivaji and the Decline of the Mughal Empire". The Journal of Asian Studies. 35 (2): 221–235. doi:10.2307/2053980. JSTOR 2053980. S2CID 162482005.

- Prakash, Om (2002). Encyclopaedic History of Indian Freedom Movement. New Delhi: Anmol Publications. ISBN 978-81-261-0938-8.

- Ramusack, Barbara N. (2004). The Indian Princes and their States. The New Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-44908-3.

- Rathod, N.G. (1994). The Great Maratha Mahadaji Scindia. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. ISBN 978-81-85431-52-9.

- Richards, John F. (1995). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2.

- Roy, Kaushik (2011). War, Culture and Society in Early Modern South Asia, 1740–1849. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-79087-4.

- Roy, Kaushik (2004). India's Historic Battles: From Alexander the Great to Kargil. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-7824-109-8.

- Saini, A.K; Chand, Hukam (n.d.). History of Medieval India. New Delhi: Anmol Publications. ISBN 978-81-261-2313-1.

- Sampath, Vikram (2008). Splendours of Royal Mysore (Paperback ed.). Rupa & Company. ISBN 978-81-291-1535-5.

- Sardesai, Govind Sakharam (1935). A History of Modern India ...: Marathi Riyasat. Vol. 2.

- Sardesai, H.S. (2002). Shivaji, the great Maratha. Cosmo Publications. ISBN 978-81-7755-286-7.

- Sarkar, Jadunath (1950). Fall of the Mughal Empire: 1754–1771. (Panipat). Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). M.C. Sarkar.

- Sarkar, Jadunath (1991). Fall of the Mughal Empire. Vol. I (4th ed.). Orient Longman. ISBN 978-81-250-1149-1.

- Sarkar, Jadunath (1994). A History of Jaipur: C. 1503–1938. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-250-0333-5.

- Sen, S.N (2006). History Modern India (3rd ed.). The New Age. ISBN 978-81-224-1774-6.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (2010). An Advanced History of Modern India. Macmillan India. pp. 1941–. ISBN 978-0-230-32885-3.

- Sheil, Lady Mary Leonora Woulfe; Sheil, Sir Justin (1856). Glimpses of Life and Manners in Persia. John Murray.

- Singh, Harbakhsh (2011). War Despatches: Indo-Pak Conflict 1965. Lancer. ISBN 978-1-935501-29-9.

- Singh, U.B. (1998). Administrative System in India: Vedic Age to 1947. APH Publishing. p. 93. ISBN 978-81-7024-928-3.

- Stewart, Gordon (1993). The Marathas 1600–1818. New Cambridge History of India. Vol. II . 4. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-03316-9.

- Trivedi, Harish; Allen, Richard (2000). Literature and Nation. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-21207-6.

- Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D. (2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires and Modern States". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 219–229. doi:10.5195/JWSR.2006.369. ISSN 1076-156X.

- Sridharan, K. (2000). Sea: Our Saviour. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-81-224-1245-1.

- United States Court of Customs and Patent Appeals (1930), Court of Customs and Patent Appeals Reports, vol. 18, Washington: Supreme Court of the United States, OCLC 2590161

- Vartak, Malavika (8–14 May 1999). "Shivaji Maharaj: Growth of a Symbol". Economic and Political Weekly. 34 (19): 1126–1134. JSTOR 4407933.

Further reading

[edit]- Ahmad, Aziz; Krishnamurti, R. (1962). "Akbar: The Religious Aspect". The Journal of Asian Studies. 21 (4): 577. doi:10.2307/2050934. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 2050934. S2CID 161932929.

- Apte, B.K. (editor) – Chhatrapati Shivaji: Coronation Tercentenary Commemoration Volume, Bombay: University of Bombay (1974–75)

- Bhosle, Prince Pratap Sinh Serfoji Raje (2017). Contributions of Thanjavur Maratha Kings (2nd ed.). Notion Press. ISBN 978-1-948230-95-7.

- Bose, MeliaBelli (2017). Women, Gender and Art in Asia, c. 1500–1900. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-53655-4.

- Breathing in Bodhi – the General Awareness/ Comprehension book – Life Skills/ Level 2 for the avid readers. Disha Publications. 2017. ISBN 978-93-84583-48-4.

- Chaturvedi, R. P. (2010). Great Personalities. Upkar Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7482-061-7.

- Chhabra, G.S. (2005). Advance Study in the History of Modern India. Vol. 1: 1707–1803. Lotus Press. ISBN 978-81-89093-06-8.

- Desai, Ranjeet – Shivaji the Great, Janata Raja (1968), Pune: Balwant Printers – English Translation of popular Marathi book.

- Edwardes, Stephen Meredyth; Garrett, Herbert Leonard Offley (1995). Mughal Rule in India. Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-7156-551-1.

- Gash, Norman (1990). Wellington: Studies in the Military and Political Career of the First Duke of Wellington. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-2974-5.

- Ghazi, M.A. (2002). Islamic Renaissance In South Asia (1707–1867) : The Role Of Shah Waliallah & His Successors. New Delhi: Adam. ISBN 978-81-7435-400-6.

- Kincaid, Charles Augustus; Pārasanīsa, Dattātraya Baḷavanta (1925). A History of the Maratha People: From the death of Shahu to the end of the Chitpavan epic. Vol. III. S. Chand.

- Majumdar, R. C. (1951). The History and Culture of the Indian People. Vol. 7: The Mughul Empire [1526–1707]. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan – via G. Allen & Unwin.

- Manohar, Malgonkar (1959). The Sea Hawk: Life and Battles of Kanoji Angrey. p. 63. OCLC 59302060.

- McDonald, Ellen E. (1968), The Modernizing of Communication: Vernacular Publishing in Nineteenth Century Maharashtra, Berkeley: University of California Press, OCLC 483944794

- McEldowney, Philip F (1966), Pindari Society and the Establishment of British Paramountcy in India, Madison: University of Wisconsin, OCLC 53790277, archived from the original on 15 May 2012, retrieved 21 October 2014

- Mehta, Jaswant Lal (2009) [1984], Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India, Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd, ISBN 978-81-207-1015-3

- Rath, Saraju (2012). Aspects of Manuscript Culture in South India. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-21900-7.

- Roy, Tirthankar (2013). "Rethinking the Origins of British India: State Formation and Military-fiscal Undertakings in an Eighteenth Century World Region". Modern Asian Studies. 47 (4): 1125–1156. doi:10.1017/S0026749X11000825. ISSN 0026-749X. S2CID 46532338.

- Schmidt, Karl J. (2015). An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-47681-8.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1994). Anglo-Maratha Relations, 1785–96. Vol. 2. Bombay: Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7154-789-0.

- Serfoji, Tanjore Maharaja (1979). Journal of the Tanjore Maharaja Serfoji's Sarasvati Mahal Library.