Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Geological history of Mars

View on Wikipedia

The geological history of Mars follows the physical evolution of Mars as substantiated by observations, indirect and direct measurements, and various inference techniques. Methods dating back to 17th-century techniques developed by Nicholas Steno, including the so-called law of superposition and stratigraphy, used to estimate the geological histories of Earth and the Moon, are being actively applied to the data available from several Martian observational and measurement resources. These include landers, orbiting platforms, Earth-based observations, and Martian meteorites.

Observations of the surfaces of many Solar System bodies reveal important clues about their evolution. For example, a lava flow that spreads out and fills a large impact crater is likely to be younger than the crater. On the other hand, a small crater on top of the same lava flow is likely to be younger than both the lava and the larger crater since it can be surmised to have been the product of a later, unobserved, geological event. This principle, called the law of superposition, along with other principles of stratigraphy first formulated by Nicholas Steno in the 17th century, allowed geologists of the 19th century to divide the history of the Earth into the familiar eras of Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic. The same methodology was later applied to the Moon[1] and then to Mars.[2]

Another stratigraphic principle used on planets where impact craters are well preserved is that of crater number density. The number of craters greater than a given size per unit surface area (usually a million km2) provides a relative age for that surface. Heavily cratered surfaces are old, and sparsely cratered surfaces are young. Old surfaces have many big craters, and young surfaces have mostly small craters or none at all. These stratigraphic concepts form the basis for the Martian geologic timescale.

Relative ages from stratigraphy

[edit]Stratigraphy establishes the relative ages of layers of rock and sediment by denoting differences in composition (solids, liquids, and trapped gasses). Assumptions are often incorporated about the rate of deposition, which generates a range of potential age estimates across any set of observed sediment layers.

Absolute ages

[edit]On Earth, the primary method for calibrating geological ages to a calendar is radiometric dating. Combining the constraints from multiple different radioisotope systems can improve the precision in an age estimate. Using stratigraphic principles, the ages of geological units can usually only be determined relative to each other. For example, Mesozoic rock strata making up the Cretaceous system lie on top of rocks of the Jurassic system, so the Cretaceous is more recent than the Jurassic. However, this tells us nothing about how long ago either the Cretaceous or Jurassic periods were, only their relative order. Absolute ages from radiometric dating are required to calibrate the stratigraphic sequence. This requires laboratory analysis of physical samples retrieved from locations with known stratigraphy, which is generally only possible for rocks on Earth. A small number of absolute ages have also been determined for rock units on the Moon, from which samples have been returned to Earth. Lunar relative ages are provided by crater counting. Although the number of calibration points is small, this has allowed the derivation of an approximate dating system for the Moon.

Assigning absolute ages to rock units on Mars is far more problematic. Numerous attempts[3][4][5] have been made over the years to determine an absolute Martian chronology (timeline) by comparing estimated impact cratering rates for Mars to those on the Moon. If the rate of impact crater formation on Mars by crater size per unit area over geologic time (the production rate or flux) is known with precision, then crater densities also provide a way to determine absolute ages.[6] Unfortunately, practical difficulties in crater counting[7] and uncertainties in estimating the flux still create huge uncertainties in the ages derived from these methods. Martian meteorites have provided datable samples that are consistent with ages calculated thus far,[8] but the locations on Mars from where the meteorites came (provenance) are unknown, limiting their value as chronostratigraphic tools. Absolute ages determined by crater density should therefore be taken with some skepticism.[9]

Crater density timescale

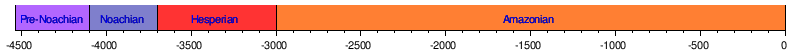

[edit]Studies of impact crater densities on the Martian surface[10] [11] have delineated four broad periods in the planet's geologic history.[12] The periods were named after places on Mars that had large-scale surface features, such as large craters or widespread lava flows, that date back to these time periods. The absolute ages given here are only approximate. From oldest to youngest, the time periods are:

- Pre-Noachian: the interval from the accretion and differentiation of the planet about 4.5 billion years ago (Gya) to the formation of the Hellas impact basin, between 4.1 and 3.8 Gya.[13] Most of the geologic record of this interval has been erased by subsequent erosion and high impact rates. The crustal dichotomy is thought to have formed during this time, along with the Argyre and Isidis basins.

- Noachian Period (named after Noachis Terra): Formation of the oldest extant surfaces of Mars between 4.1 and about 3.7 Gya. Noachian-aged surfaces are scarred by many large impact craters. The Tharsis bulge is thought to have formed during the Noachian, along with extensive erosion by liquid water producing river valley networks. Large lakes or oceans may have been present.

- Hesperian Period (named after Hesperia Planum): 3.7 to approximately 3.0 Gya. It is marked by the formation of extensive lava plains. The formation of Olympus Mons probably began during this period.[14] Catastrophic releases of water carved out extensive outflow channels around Chryse Planitia and elsewhere. Ephemeral lakes or seas may have formed in the northern lowlands.

- Amazonian Period (named after Amazonis Planitia): 3.0 Gya to present. Amazonian regions have few meteorite impact craters but are otherwise quite varied. Lava flows, glacial/periglacial activity, and minor releases of liquid water continued during this period.[15]

Epochs:

The date of the Hesperian/Amazonian boundary is particularly uncertain and could range anywhere from 3.0 to 1.5 Gya.[16] Basically, the Hesperian is thought of as a transitional period between the end of heavy bombardment and the cold, dry Mars seen today.

Mineral alteration timescale

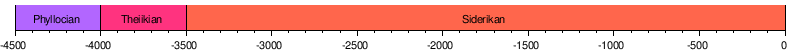

[edit]In 2006, researchers using data from the OMEGA Visible and Infrared Mineralogical Mapping Spectrometer on board the Mars Express orbiter proposed an alternative Martian timescale based on the predominant type of mineral alteration that occurred on Mars due to different styles of chemical weathering in the planet's past. They proposed dividing the history of Mars into three eras: the Phyllocian, Theiikian and Siderikan.[17][18]

- The Phyllocian (named after phyllosilicate or clay minerals that characterize the era) lasted from the formation of the planet until around the Early Noachian (about 4.0 Gya). OMEGA identified outcroppings of phyllosilicates at numerous locations on Mars, all in rocks that were exclusively Pre-Noachian or Noachian in age (most notably in rock exposures in Nili Fossae and Mawrth Vallis). Phyllosillicates require a water-rich, alkaline environment to form. The Phyllocian era correlates with the age of valley network formation on Mars, suggesting an early climate that was conducive to the presence of abundant surface water. It is thought that deposits from this era are the best candidates in which to search for evidence of past life on the planet.

- The Theiikian (named after sulphurous in Greek, for the sulphate minerals that were formed) lasted until about 3.5 Gya. It was an era of extensive volcanism, which released large amounts of sulphur dioxide (SO2) into the atmosphere. The SO2 combined with water to create a sulphuric acid-rich environment that allowed the formation of hydrated sulphates (notably kieserite and gypsum).

- The Siderikan (named for iron in Greek, for the iron oxides that formed) lasted from 3.5 Gya until the present. With the decline of volcanism and available water, the most notable surface weathering process has been the slow oxidation of the iron-rich rocks by atmospheric peroxides producing the red iron oxides that give the planet its familiar colour.

References

[edit]- ^ For reviews of this topic, see:

- Mutch, T. A. (1970). Geology of the Moon: A Stratigraphic View. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Wilhelms, D. E. (1987). The Geologic History of the Moon. Bibcode:1987ghm..book.....W. USGS Professional Paper 1348.

- ^ Scott, D. H.; Carr, M. H. (1978). Geologic Map of Mars. Reston, Virginia: United States Geological Survey. Miscellaneous Investigations Set Map 1-1083.

- ^ Neukum, G.; Wise, D.U. (1976). "Mars: A Standard Crater Curve and Possible New Time Scale". Science. 194 (4272): 1381–1387. Bibcode:1976Sci...194.1381N. doi:10.1126/science.194.4272.1381. PMID 17819264.

- ^ Neukum, G.; Hiller, K. (1981). "Martian ages". J. Geophys. Res. 86 (B4): 3097–3121. Bibcode:1981JGR....86.3097N. doi:10.1029/JB086iB04p03097.

- ^ Hartmann, W. K.; Neukum, G. (2001). "Cratering Chronology and Evolution of Mars". In Kallenbach, R.; et al. (eds.). Chronology and Evolution of Mars. Space Science Reviews. Vol. 12. pp. 105–164. ISBN 0792370511.

- ^ Hartmann, W.K. (2005). "Martian Cratering 8: Isochron Refinement and the Chronology of Mars". Icarus. 174 (2): 294. Bibcode:2005Icar..174..294H. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.11.023.

- ^ Hartmann, W.K. (2007). "Martian cratering 9: Toward Resolution of the Controversy about Small Craters". Icarus. 189 (1): 274–278. Bibcode:2007Icar..189..274H. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.02.011.

- ^ Hartmann 2003, p. 35

- ^ Carr 2006, p. 40

- ^ Tanaka, K. L. (1986). "The Stratigraphy of Mars". Journal of Geophysical Research, Seventeenth Lunar and Planetary Science Conference Part 1, 91(B13), E139–E158.

- ^ Melosh, H.J., 2011. Planetary surface processes. Cambridge Univ. Press., pp. 500

- ^ Caplinger, Mike. "Determining the age of surfaces on Mars". Archived from the original on February 19, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-02.

- ^ Carr, M. H.; Head, J. W. (2010). "Geologic History of Mars". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 294 (3–4): 185–203. Bibcode:2010E&PSL.294..185C. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.06.042.

- ^ Fuller, Elizabeth R.; Head, James W. (2002). "Amazonis Planitia: The role of geologically recent volcanism and sedimentation in the formation of the smoothest plains on Mars". Journal of Geophysical Research. 107 (E10): 5081. Bibcode:2002JGRE..107.5081F. doi:10.1029/2002JE001842.

- ^ Salese, F.; Di Achille, G.; Neesemann, A.; Ori, G. G.; Hauber, E. (2016). "Hydrological and sedimentary analyses of well-preserved paleofluvial-paleolacustrine systems at Moa Valles, Mars". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 121 (2): 194–232. Bibcode:2016JGRE..121..194S. doi:10.1002/2015JE004891.

- ^ Hartmann 2003, p. 34

- ^ Williams, Chris. "Probe reveals three ages of Mars". The Register. Retrieved 2007-03-02.

- ^ Bibring, Jean-Pierre; Langevin, Y; Mustard, JF; Poulet, F; Arvidson, R; Gendrin, A; Gondet, B; Mangold, N; et al. (2006). "Global Mineralogical and Aqueous Mars History Derived from OMEGA/Mars Express Data". Science. 312 (5772): 400–404. Bibcode:2006Sci...312..400B. doi:10.1126/science.1122659. PMID 16627738.

Citations

[edit]- Carr, Michael, H. (2006). The Surface of Mars. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87201-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hartmann, William, K. (2003). A Traveler's Guide to Mars: The Mysterious Landscapes of the Red Planet. New York: Workman. ISBN 0-7611-2606-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

[edit]- Mars - Geologic Map (USGS, 2014) (original / crop / full / video (00:56)).

Geological history of Mars

View on GrokipediaFormation and Early Evolution

Accretion and Differentiation

The formation of Mars began approximately 4.6 billion years ago through the accretion of planetesimals within the protoplanetary disk surrounding the young Sun.[5] This process involved the gravitational aggregation of dust grains and rocky fragments in the inner solar system, where Mars assembled from materials primarily sourced from regions within about 1.5 AU of the Sun.[6] Unlike Earth, which grew larger through extended collisions, Mars achieved its comparatively modest size— with an equatorial radius of approximately 3390 km and a mass of about 0.107 Earth masses—due to a sparser distribution of planetesimals beyond its orbit, influenced by the gravitational perturbations from migrating giant planets like Jupiter, which limited further accretion and left the region between Mars and Jupiter relatively depleted.[7][8] Following accretion, Mars underwent rapid internal differentiation within roughly 10 million years, driven by heat from impacts, radioactive decay, and possibly short-lived isotopes. During this phase, denser iron-nickel alloys sank toward the center under gravity, forming a metallic core with a radius estimated at around 1800 km, while lighter silicate materials rose to create a surrounding mantle and an overlying basaltic crust.[9] This core-mantle separation occurred faster than on Earth, reflecting Mars' smaller size and lower heat budget, which allowed the planet to cool more quickly and solidify its internal structure early in its history. Key evidence for this early differentiation comes from SNC meteorites—shergottites, nakhlites, and chassignites—ejected from Mars and found on Earth, which preserve isotopic signatures indicating core formation and mantle evolution within the first few million years after planetary assembly.[10] These meteorites also record thermoremanent magnetization, suggesting that Mars generated a dynamo-driven magnetic field in its first 100 million years, powered by convection in the molten core before it cooled sufficiently to cease. An initial atmosphere on Mars formed concurrently through volcanic outgassing and impact-induced degassing, releasing volatiles from the planet's interior and captured materials. This primordial atmosphere was dominated by carbon dioxide (CO₂), nitrogen (N₂), and water vapor (H₂O), with contributions from both endogenic volcanism and exogenic delivery during accretion.[11][12]Late Heavy Bombardment and Primordial Crust

The Late Heavy Bombardment (LHB) represents a cataclysmic phase of intense meteoritic impacts on Mars, occurring approximately 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago (Ga), shortly after the planet's primary accretion.[13][14] This event is hypothesized to have been triggered by the dynamical instability and migration of the giant planets in the early solar system, which destabilized asteroid and comet orbits, leading to a flux of impactors across the inner planets.[15] On Mars, the LHB profoundly reshaped the surface, excavating vast basins and contributing to the planet's early geological framework. Prominent features from this era include the formation of enormous impact basins such as Hellas Planitia and Argyre Planitia, which attest to the scale of bombardment. Hellas Planitia, the largest recognized impact structure on Mars, spans a diameter of about 2,300 km and reaches depths of approximately 7 km below the planetary datum, while Argyre Planitia measures over 1,500 km across with depths exceeding 4 km.[16][17][18] Topographic profiles from instruments like the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) and gravity anomalies mapped by missions including the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) reveal the multi-ring structures and isostatic rebound of these basins, indicating impacts by protoplanet-sized bodies during the LHB.[19][20] Concurrent with these impacts, the primordial crust of Mars developed through the solidification of a global magma ocean, forming the ancient highland terrains that dominate the southern hemisphere. This process involved the fractional crystallization of the magma ocean, where plagioclase-rich materials floated to form an anorthositic upper crust, similar to lunar highlands but adapted to Mars' larger size and composition.[21][22] The resulting crust, estimated at 40-50 km thick in highland regions, provided a stable foundation that was later modified by impacts and early volcanism. The LHB and crustal formation also coincided with the decline of Mars' early magnetic dynamo, driven by rapid core cooling that diminished convective vigor and led to the cessation of the global magnetic field by around 4 Ga.[23] Evidence for this timeline comes from the remanent magnetization preserved in ancient crustal rocks, particularly in the southern highlands, where thermoremanent signatures indicate a dynamo active until approximately 4.1 Ga but absent thereafter.[24][25] Impacts during the LHB delivered significant volatiles, including water, through cometary and asteroidal projectiles, introducing an initial hydrological inventory that enabled the formation of early surface features like transient water flows and possible lakes.[26][27] This water enrichment, estimated to account for 6-27% of Earth's ocean equivalent, set the stage for subsequent Noachian-era aqueous activity without dominating the bombardment narrative.[28]Chronological Framework

Noachian Period

The Noachian Period spans approximately 4.1 to 3.7 billion years ago (Ga), marking the end of the Late Heavy Bombardment (LHB) and the onset of reduced impact cratering rates on Mars.[29][30] This era represents the planet's earliest named geological epoch, during which the primordial crust underwent intense modification through impacts, early tectonic activity, and the initial stabilization of surface features. The period's boundaries are primarily defined through crater counting techniques calibrated against lunar samples, with the Noachian-Hesperian transition occurring at a cumulative crater density of N(1) = 100 craters larger than 1 km in diameter per 10^6 km². During the Noachian, the southern highlands formed as vast, heavily cratered terrains, characterized by densely packed impact craters exceeding 1 km in diameter, with densities often surpassing 100 per 10^6 km². These highlands, comprising much of the planet's southern hemisphere, exhibit rugged, dissected landscapes that preserve evidence of the era's high bombardment flux, which saturated the surface with craters before significant erosion or resurfacing could occur. Early volcanic activity contributed to the formation of ridged plains, particularly in transitional zones, where basaltic flows began to infill low-lying areas amid ongoing impacts.[31] The Borealis Basin in the northern lowlands may have hosted an ocean, as suggested by its vast topographic depression, associated hydrated minerals, and recent (2025) imaging of potential coastal deposits, supporting the hypothesis of widespread water coverage during this time.[32][33] Widespread fluvial activity is evident across Noachian terrains, with valley networks incising the southern highlands, such as those in Terra Cimmeria, indicating episodic surface runoff and erosion by liquid water.[34] Spectral analysis by the CRISM instrument on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has detected abundant clay minerals (phyllosilicates) in these ancient outcrops, pointing to aqueous alteration under neutral to alkaline conditions prevalent in the Noachian.[35] These features collectively suggest a dynamic hydrological regime, though limited by the era's intense cratering. Recent Perseverance rover findings in Jezero Crater (as of 2025) reveal evidence of early fluid activity and potential biosignatures in Noachian rocks, refining models of ancient habitability.[36] Atmospheric conditions during the Noachian supported liquid water stability, with models indicating a thicker CO₂-dominated atmosphere of approximately 0.1–1 bar surface pressure.[37] This denser atmosphere likely shielded the surface from extreme cold and low pressure, enabling transient warm and wet episodes. The global magnetic field is estimated to have declined between approximately 4.1 and 3.7 Ga, possibly extending into the early Hesperian, exposing the atmosphere to solar wind stripping and initiating gradual volatile loss through sputtering and hydrodynamic escape.[38] This transition set the stage for intensified volcanism in the subsequent Hesperian Period.Hesperian Period

The Hesperian Period represents a transitional phase in Martian geological history, characterized by intermediate impact crater densities and the widespread emplacement of ridged plains material, which distinguishes it from the heavily cratered Noachian terrains and the sparsely cratered Amazonian surfaces. This period is dated to approximately 3.7 to 3.0 billion years ago (Ga), based on stratigraphic correlations and crater counting models.[40] During this time, Mars experienced a decline in the rate of impact bombardment compared to the Noachian, allowing other processes like volcanism and fluvial activity to dominate surface modification. The ridged plains, primarily volcanic in origin, cover extensive regions such as Hesperia Planum and the northern lowlands, exhibiting subtle wrinkle ridges formed by compressive stresses.[41] A hallmark of the Hesperian was the peak development of the Tharsis bulge, a massive volcanic province that drove significant crustal deformation and resurfacing. This era saw the formation of precursors to giant shield volcanoes, including early stages of Olympus Mons and the Tharsis Montes, accompanied by flooding basalts that covered about 30% of the planet's surface, particularly in the southern highlands and northern plains. These voluminous eruptions, sourced from long-lived mantle plumes beneath Tharsis, produced ridged and smooth plains units, with thicknesses reaching several kilometers in places, as mapped from orbital data. The Tharsis region's growth also induced radial fractures and grabens, altering global stress fields and facilitating later tectonic features.[41] Catastrophic hydrological events defined much of the Hesperian surface, with massive outflow channels such as Kasei Valles originating from chaotic terrains and troughs in Valles Marineris, leading to erosion of canyon walls and deposition of sediments across Chryse Planitia. These floods, likely triggered by the release of subsurface aquifers heated by Tharsis volcanism, carved channels up to hundreds of kilometers wide and deposited layered sediments observable in Viking orbiter images and higher-resolution Mars Global Surveyor altimetry and imagery.[42] Concurrently, sulfate-rich deposits formed in regions like Meridiani Planum, signaling episodic acidic water bodies where evaporation concentrated minerals such as jarosite in sedimentary layers up to 25 wt% SO₃, as identified by orbital spectroscopy.[43] These deposits indicate fluctuating environmental conditions with acidic lakes or groundwater interactions. Recent Perseverance rover analyses in Jezero Crater (as of 2025) indicate episodic water flows and sedimentation, with mudstones containing organics potentially linked to ancient microbial life.[36][41] Tectonic activity during the Hesperian included the formation of lobate scarps, thrust faults manifesting as arcuate scarps up to several kilometers long, resulting from global contraction as the planet cooled. Analysis of these features, combined with geophysical models informed by InSight mission seismic data on interior structure, suggests ongoing global contraction due to planetary cooling.[44] This contraction was particularly pronounced in Tharsis-proximal regions, where it interacted with extensional rifting to shape Valles Marineris.[41]Amazonian Period

The Amazonian Period, spanning approximately 3.0 billion years ago to the present, represents the most recent and longest era in Martian geological history, characterized by a marked decline in major geological activity and low crater densities of less than 5 craters per 10^6 km² on young surfaces, indicating relatively recent resurfacing.[40][45] This period follows the more dynamic Hesperian, with a brief continuity of outflow activity transitioning into the calmer Amazonian regime.[46] Overall, the era features episodic localized processes rather than widespread global changes, shaped by ongoing atmospheric interactions and orbital variations.[45] Volcanism during the Amazonian was sporadic and concentrated in the Tharsis region, with the largest shield volcano, Olympus Mons, showing evidence of late-stage activity. Crater counting on lava flows from Mars Express High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) data reveals ages ranging from 100-200 million years at the summit plateau to as young as 2 million years on certain distal slopes, suggesting eruptions continued into the recent past.[47][48] These findings indicate that while volcanic output waned significantly after the Hesperian, isolated effusive events persisted, contributing to the construction of the volcano's immense flanks.[49] The polar regions saw the accumulation of extensive layered deposits during the Amazonian, particularly in Planum Boreum (north) and Planum Australe (south), where water ice intermixed with dust formed stacks up to 3 km thick.[50] These layers, revealed by radar sounders like SHARAD on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, record cycles of deposition and erosion driven by variations in Mars' obliquity, which alter insolation and atmospheric circulation patterns over tens of thousands of years.[51][52] Obliquity shifts between about 15° and 35° have promoted repeated expansion and contraction of polar ice caps, preserving a climatic archive in the stratified sequences.[51] In equatorial and mid-latitude regions, recurring slope lineae (RSL)—dark, seasonally appearing streaks observed by the HiRISE camera—are interpreted by recent studies (as of 2025) as dry granular flows, such as sand avalanches on steep slopes, with minimal or no involvement of liquid water.[53] These features, up to hundreds of meters long, form on steep slopes during warmer months.[54][55] A global dust mantle, typically a few centimeters to a meter thick, has accumulated across much of the planet during the Amazonian, blanketing older terrains and facilitating wind-driven erosion.[56] In areas like Arabia Terra, this mantle has been sculpted by prevailing winds into yardangs—streamlined ridges aligned with wind direction—evidencing ongoing aeolian modification of the landscape.[57] Dust storms, including planet-encircling events, redistribute material and contribute to the mantle's uniformity, with erosion rates varying by local topography and storm frequency.[56]Key Geological Processes

Impact Cratering

Impact cratering has profoundly shaped the surface of Mars, creating a record of its bombardment history and influencing other geological processes. Meteoroids, ranging from small asteroids to comets, collide with the planet at hypervelocities, excavating craters that reveal subsurface materials and drive surface modification. Unlike Earth, Mars' thin atmosphere and lack of plate tectonics preserve these features, allowing scientists to study impacts across billions of years. The process is governed by the planet's gravity (about 3.7 m/s²), surface composition, and atmospheric interactions, which affect ejecta distribution and crater morphology.[58] The formation of an impact crater on Mars occurs in three main stages: contact and compression, excavation, and modification. During the initial contact phase, the impactor compresses the target material, generating intense shock waves that vaporize parts of both the projectile and surface. This is followed by the excavation stage, where the expanding shock wave ejects material, forming a transient crater approximately 1.5–2 times the impactor's final diameter. The modification stage involves gravitational collapse of the unstable crater walls, redistributing material to form the final structure. Ejecta blankets, often layered and extending beyond the crater rim, are emplaced ballistically during excavation and modified by atmospheric interactions on Mars, sometimes forming fluidized lobes due to entrained air or volatiles.[59][60] Martian craters are classified as simple or complex based on diameter. Simple craters, typically less than 7 km in diameter, exhibit a bowl-shaped morphology with raised rims and depth-to-diameter ratios around 0.2. Larger impacts, exceeding 7 km, produce complex craters featuring central peaks, terraced walls, and sometimes peak rings, resulting from more extensive collapse during modification. The transition diameter varies slightly with latitude and target properties but is generally around 7 km, reflecting Mars' lower gravity compared to Earth, which results in complex structures forming at larger diameters than on Earth.[61][58] Craters are unevenly distributed across Mars, with higher densities in the heavily cratered southern highlands, which preserve ancient impacts, compared to the smoother northern lowlands where resurfacing has erased many features. Orbital mapping has identified approximately 384,000 craters larger than 1 km in diameter globally, reflecting this dichotomy and indicating the northern plains underwent significant modification, possibly by volcanism or water flows. Crater density gradients highlight the hemispheric dichotomy, with the south showing saturation in older terrains.[61][62] The impact flux on Mars was elevated during the Noachian period, contributing to widespread resurfacing, and has declined exponentially since, following solar system-wide trends. This decrease aligns with the dynamical evolution of asteroid and comet populations, with fewer large impactors today. Current orbital surveys estimate the production rate at approximately 2 × 10^{-6} km^{-2} yr^{-1} for craters around 8–10 m in diameter, though rates for larger craters are orders of magnitude lower. Crater density measurements on young surfaces, such as those from recent missions, confirm this low modern flux. InSight seismic data (2018-2022) have detected impacts, confirming ongoing activity.[63][64][65] Beyond excavation, impacts generate secondary effects that extend their influence. Seismic waves from large events propagate globally, causing shaking that can trigger landslides or disrupt surface deposits far from the crater. The Martian atmosphere produces blast waves upon impact, eroding or redistributing material and contributing to dust storms. Shock heating melts significant portions of the target and impactor, forming melt sheets or pools that cool to create breccias; in ice-rich regions, this melting can initiate localized hydrothermal systems, circulating hot fluids through fractured rock for potentially thousands of years. These systems may have altered minerals and supported transient aqueous environments.[65][66] Notable impact features on Mars include rayed craters, such as Corinto in Elysium Planitia, a 14 km-diameter crater formed about 2 million years ago, whose bright rays of fresh ejecta extend over 2,000 km and reveal underlying materials through thermal contrasts. Pedestal craters, common at mid-to-high latitudes, feature elevated ejecta blankets that act as protective caps, preserving underlying ice deposits from sublimation and indicating past climate conditions with widespread volatiles. These morphologies highlight how impacts interact with Mars' volatile inventory.[67][68] Crater densities serve as a primary tool for relative dating of Martian surfaces through analysis of accumulation rates.[61]Volcanism and Tectonics

Mars' volcanism is predominantly characterized by the formation of large shield volcanoes, which are built from successive layers of low-viscosity basaltic lavas erupted over extended periods.[69] These structures, such as the Tharsis Montes (including Arsia, Pavonis, and Ascraeus Mons), rise to elevations of up to about 18 km above the surrounding plains, such as Ascraeus Mons, far surpassing Earth's largest shields like Mauna Loa.[70] The basaltic compositions of these lavas derive from partial melting of the mantle induced by upwelling plumes, as evidenced by geochemical analyses of Martian meteorites and orbital spectroscopy.[71] Unlike explosive styles dominant on Earth, Martian volcanism favors effusive eruptions due to the planet's lower gravity and the fluid nature of its magmas. InSight seismic data (2018-2022) indicate subdued mantle convection supporting late-stage volcanism.[69][72] The Tharsis province, a vast volcanic bulge spanning thousands of kilometers, exemplifies the role of hotspot activity in shaping Mars' surface. This region formed through prolonged uplift beginning around 3.5 billion years ago, driven by a stationary mantle plume that caused isostatic compensation of the lithosphere.[73] The resulting topographic rise, up to 10 km high, induced global stresses that propagated tectonic deformation across the planet, influencing features far beyond Tharsis itself.[74] Volcanic construction atop this uplift further loaded the crust, amplifying flexural responses and contributing to the province's immense scale. Similar, though smaller, hotspot-related volcanism occurred in the Elysium region, forming additional shield volcanoes like Elysium Mons.[71] Tectonic activity on Mars is closely linked to volcanic loading and planetary cooling, manifesting in distinct structural styles without evidence of plate tectonics. Around the Tharsis bulge, radial fractures and grabens extend outward for over 4,000 km, resulting from extensional stresses induced by the uplift and isostatic rebound.[75] In the Elysium province, thrust faults dominate, accommodating compression from volcanic edifice loading on a thickening lithosphere.[76] Wrinkle ridges, common across the southern highlands and northern plains, represent shallow blind thrusts formed by global lithospheric compression during cooling, with individual structures recording up to several kilometers of shortening.[76] These features highlight a one-plate tectonic regime where internal stresses drive deformation.[75] Mars has lost heat primarily through conduction since early in its history, lacking the convective renewal of plate tectonics seen on Earth. Current mantle convection persists at a subdued level, as inferred from seismic data collected by the InSight mission, which detected low-frequency marsquakes indicative of deep interior dynamics.[72] Surface heat flow today is approximately 20-24 mW/m², reflecting a cooled interior with limited upwelling.[72] This low flux supports sporadic, late-stage volcanism but underscores the planet's overall thermal stagnation.[77] Eruptions on Mars produced diverse products beyond surface flows, including extensive lava tubes that facilitated long-distance transport of molten material.[78] Ash deposits and pyroclastic materials are present but rare, largely because the low viscosity of basaltic lavas minimized explosive fragmentation during ascent and eruption.[79] These effusive products blanketed vast areas, preserving layered sequences in regions like Tharsis.[69] Volcanic activity in the Hesperian period, particularly in Tharsis, is associated with outflow channel formation possibly triggered by magma-induced crustal fracturing.[69]Hydrological and Sedimentary Activity

Evidence for ancient fluvial activity on Mars includes dendritic valley networks, which are branching systems resembling terrestrial river valleys. These networks, primarily located in the heavily cratered Noachian highlands, exhibit lengths typically ranging from 100 to 500 km and are characterized by tributary junctions and integrated drainage patterns.[80] Their formation has been attributed to either prolonged surface runoff driven by precipitation under a denser early atmosphere or groundwater sapping from subsurface aquifers, with the branching geometry supporting both mechanisms but favoring precipitation in regions with sustained flow.[81] Such networks indicate episodic or persistent liquid water flow that eroded the surface during the Noachian and Hesperian periods, contributing to the planet's early landscape modification.[80] Paleolakes and associated deltas provide direct evidence of standing bodies of water and sediment deposition. In Gale Crater, the Curiosity rover has analyzed layered sedimentary rocks within the Murray formation, revealing fine-grained mudstones and siltstones that accumulated in a lake environment.[82] These deposits contain smectite clay minerals, which form under neutral to slightly alkaline pH conditions, suggesting the ancient lake waters were habitable and supported mineral precipitation without extreme acidity.[83] Deltaic features at the crater's rim further indicate sediment transport from inflowing rivers, with layers recording multiple episodes of lake level fluctuations and deposition over extended periods.[82] Catastrophic outflow channels represent another major mode of hydrological activity, formed by massive releases of water from breached aquifers. These channels, such as those in Chryse Planitia, exhibit widths up to tens of kilometers and lengths exceeding 2000 km, with erosional features like scalloped margins and streamlined islands indicating high-velocity floods.[84] The mechanism involves the sudden failure of subsurface reservoirs, possibly through tectonic or thermal weakening, leading to megafloods with peak discharges exceeding 10^7 m³/s—orders of magnitude greater than modern terrestrial rivers.[85] Such events sculpted vast plains and transported sediments across regional scales, with the islands forming from resistant materials sculpted by the turbulent flow.[84] Sedimentary rocks in impact craters preserve records of water-mediated deposition and potential organic preservation. In Jezero Crater, the Perseverance rover has identified stratified deltaic and lacustrine deposits, including mudstones and sandstones that document an ancient river-lake system. Ongoing analyses (as of 2025) have detected organic molecules associated with these sediments, often linked to mineral matrices like carbonates and sulfates, though their origins are interpreted as primarily abiotic, resulting from geological processes such as serpentinization or atmospheric delivery rather than biological activity.[86] These findings highlight the role of sedimentation in trapping and concentrating organics, providing context for Mars' potential for prebiotic chemistry.[86] Following approximately 3 billion years ago, Mars' hydrological activity declined sharply due to global cooling, atmospheric thinning from solar wind stripping, and the loss of a protective magnetic field.[87] Surface liquid water became unstable, transitioning to ice or vapor, with much of the remaining inventory sequestered in the subsurface as hydrated minerals or permafrost.[88] Limited activity persisted in the form of subsurface aquifers or transient seasonal brines, where salts lower the freezing point to allow brief episodes of deliquescence, though these are confined and not indicative of widespread surface flow.[89] This shift marked the end of Mars' wetter epochs, reshaping its geology toward aridity.[87]Aeolian and Periglacial Processes

Aeolian processes on Mars involve wind-driven erosion, transportation, and deposition of sediments, shaping much of the planet's surface under its thin atmosphere with a mean surface pressure of approximately 6 mbar.[90] Barchan dunes, crescent-shaped sand accumulations with horns pointing downwind, are prominent examples, particularly in the Nili Patera caldera where they reach heights of 10 to 30 meters and exhibit high symmetry due to consistent wind regimes.[91] Dust devils, vortex-like whirlwinds, actively remove fine surface dust, exposing darker underlying materials and creating transient dark streaks across the landscape, as observed in regions like Gusev crater.[92] Ventifacts, rocks sculpted by wind abrasion from saltating sand particles, are widespread and indicate that aeolian erosion is a dominant force, with features such as elongated pits, flutes, and grooves forming through kinetic energy impacts rather than dust alone.[93] Global dust storms, occurring roughly every three Mars years, dramatically illustrate the scale of aeolian activity by lifting vast quantities of dust—estimated at around 10^15 kilograms—into the atmosphere, which temporarily alters surface albedo, reduces sunlight reaching the surface, and influences regional climate patterns.[94] These events have been extensively documented by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, revealing their role in redistributing fine particles across hemispheres and contributing to the planet's hazy skies.[94] Recent observations confirm ongoing dune migration, with rates of about 1 meter per year in areas like Nili Patera, underscoring the persistence of wind-driven sediment transport despite the tenuous atmosphere.[91] Periglacial processes on Mars, driven by freeze-thaw cycles and ice sublimation in cold, dry conditions, produce distinctive landforms linked to ground ice. In Utopia Planitia, polygonal terrains form through thermal contraction cracking of ice-cemented regolith, creating networks of troughs that indicate past or present near-surface ice volumes, with patterns resembling ice-wedge polygons on Earth.[95] Gullies on steep slopes, often found in mid-latitude craters and dunes, are attributed to seasonal CO2 frost accumulation during winter, which sublimates in spring and triggers dry avalanches or granular flows that erode and transport regolith downslope.[96] These features show recent activity, with fresh deposits observed over multiple Mars years. Sublimation of volatile ices further sculpts polar regions, notably forming "swiss cheese" terrain in the south polar residual cap, where CO2 ice layers develop interconnected pits up to 10 meters deep through seasonal retreat and vaporization. This pitted morphology evolves annually, with scarps retreating as sunlight penetrates the translucent ice, exposing and removing underlying material. Overall, these aeolian and periglacial processes overprint older terrains, including ancient fluvial features, to dominate the Amazonian epoch's landscape evolution.[91]Methods for Determining Geological Ages

Stratigraphic and Relative Dating

Stratigraphic and relative dating on Mars employs established geological principles to determine the sequence of events and rock unit ages without relying on numerical chronology. The principle of superposition asserts that in undeformed sedimentary sequences, younger layers overlie older ones, allowing researchers to infer temporal order from vertical stacking. Cross-cutting relationships further refine this by indicating that intrusive features, such as dikes or faults, are younger than the units they intersect. Additionally, the inclusion of fragments—where clasts within a rock unit must predate the enclosing material—helps establish relative ages in breccias and conglomerates common on the Martian surface. These principles, adapted from terrestrial stratigraphy, form the basis for mapping Martian rock sequences despite the planet's lack of plate tectonics and extensive modification by impacts and erosion.[97] On Mars, these methods have been applied extensively to map superposed units, particularly in regions like Valles Marineris, where Hesperian-age lavas and layered deposits overlie Noachian basement rocks, revealing a transition from ancient crust to later volcanic resurfacing. In the chasmata walls, Noachian fractured plains and megabreccias are conformably overlain by Hesperian sulfates and lavas, with cross-cutting faults providing evidence of post-depositional tectonism. Such relationships demonstrate episodic deposition and erosion, with included Noachian fragments in Hesperian units confirming the basement's antiquity. Global stratigraphy, initially delineated from Mariner 9 imagery and refined by Viking Orbiter data, divides the surface into three primary systems: Noachian highland units characterized by heavily cratered, dissected terrains; Hesperian ridged plains marked by wrinkle-ridge volcanics in regions like Hesperia Planum; and Amazonian smooth plains, including low-relief deposits in the northern lowlands that bury older materials. This framework, formalized in the 1:25,000,000-scale geologic map, relies on superposition and cross-cutting to correlate units across hemispheres, highlighting a progression from impact-dominated highlands to volcanic plains and finally to aeolian and periglacial veneers.[98] However, Martian stratigraphy faces limitations due to pervasive erosion and burial, which obscure unit contacts and complicate sequence reconstruction. Wind and mass wasting have degraded highland terrains, exhuming basement while removing diagnostic layers, while extensive young mantles—icy-dusty deposits of Amazonian age—cover a significant portion of the mid-to-high latitudes, masking underlying stratigraphy and preventing direct observation of older contacts in up to half the surface area. These challenges necessitate careful mapping to distinguish erosional unconformities from depositional hiatuses. To overcome them, integration with high-resolution imagery from the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) enables stereo-derived digital elevation models, facilitating three-dimensional reconstructions of stratigraphic columns in layered terrains like those in craters and chasmata. Such 3D views reveal subtle dips, thicknesses, and erosional features invisible in 2D images, enhancing the precision of relative dating. This approach complements crater density analysis by providing sequence-based constraints on event order.[97][99]Crater Density Analysis

Crater density analysis serves as a primary method for establishing relative ages of Martian surfaces by quantifying the accumulation of impact craters over time. This technique involves measuring the cumulative frequency of craters greater than a specific diameter D km per unit area, typically expressed as craters per million square kilometers. A standard index, denoted N(1), counts craters larger than 1 km in diameter and provides a normalized measure of surface exposure duration, assuming a constant influx of impactors. Higher densities indicate older surfaces that have retained more craters, while lower densities suggest younger terrains modified by resurfacing processes. This approach relies on high-resolution orbital imagery to identify and size craters, often automated for efficiency in large-scale mapping. Calibration of crater densities to chronological timescales uses isochrons, which are model curves linking observed crater frequencies to absolute time based on production rates derived from lunar cratering records. For Mars, these isochrons are scaled to account for differences in impact flux and environmental conditions, with the lunar-to-Mars cratering ratio estimated at approximately 0.8–1.7 over the past 3.5 billion years. Representative values include N(1) ≈ 100 for typical Noachian surfaces, corresponding to ages around 3.7–4.1 billion years ago, and N(1) ≈ 10 for Hesperian terrains, dating to about 3.0–3.7 billion years ago. These benchmarks stem from comparisons with dated lunar maria and highlands, adjusted for Mars' lower gravity and atmospheric effects on small impactors. Recent seismic data from the InSight mission, analyzed as of 2024, indicate an enhanced recent impact flux (potentially 2–10 times higher than prior estimates for craters >8 m in diameter), which may require adjustments to models for Amazonian-age surfaces.[65] The underlying production functions describe how crater sizes accumulate according to scaling laws, where the cumulative number of craters π(D) follows a power-law relation π(D) ∝ D-*a, with exponent a typically ranging from 2 to 3 for primary craters on Mars. This distribution reflects the decreasing frequency of larger impacts and is modified for Mars' surface gravity of 0.38 gEarth, which influences crater morphology and diameter through pi-scaling parameters in impact models. Gravity scaling reduces the size of transient craters compared to the Moon, necessitating adjustments to lunar-derived functions to fit observed Martian size-frequency distributions. Significant uncertainties arise from geological processes that alter crater populations, such as erasure through volcanism, erosion, or burial, which can underestimate ages on modified terrains. Additionally, secondary craters—ejected from primary impacts—can inflate counts, particularly for small diameters (<1 km), leading to erroneously young ages; this is mitigated by focusing on size-frequency distributions that distinguish primary from secondary populations through slope changes in the cumulative plots. Stratigraphic context aids in identifying uniform geological units for accurate counting areas. Applications of crater density analysis have refined timelines for key features, such as the young lava flows in Athabasca Valles, dated to approximately 10 million years ago based on low N(1) values (~0.1–1) derived from Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) infrared data. This method has mapped Amazonian-age resurfacing across the Cerberus plains, highlighting recent volcanic activity.Absolute Dating Techniques

Absolute dating techniques on Mars provide numerical ages in years, primarily through radiometric methods applied to meteorites and in-situ measurements, offering calibration points for the planet's geological timeline. These approaches rely on the decay of radioactive isotopes in rocks and minerals, yielding crystallization ages that reflect igneous formation events and exposure ages that indicate surface burial or ejection histories. Unlike relative methods, absolute dating establishes precise chronologies, though challenges persist due to limited sample access and environmental factors on Mars. The primary source of absolute ages comes from SNC (Shergottite-Nakhlite-Chassignite) meteorites, which are widely accepted as Martian in origin based on their chemical and isotopic similarities to measurements from orbiters and landers. Radiometric dating using Rb-Sr and Sm-Nd isochrons on these meteorites reveals crystallization ages spanning a broad range: shergottites yield young ages of approximately 150-575 million years ago (Ma), while nakhlites and chassignites indicate around 1.3 billion years ago (Ga), and the orthopyroxenite ALH 84001 provides an ancient crystallization age of about 4.5 Ga. Additionally, cosmic ray exposure ages, determined from tracks and nuclides produced by galactic cosmic rays, average around 10 Ma for most SNC meteorites, suggesting relatively recent ejection from Mars following impact events. These ages highlight episodic volcanic activity on Mars extending into the geologically recent past. In-situ absolute dating has been achieved by NASA's Curiosity rover in Gale Crater using the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument suite, which measures argon isotopes in conjunction with potassium abundances from the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS). This K-Ar method dated a mudstone in the Sheepbed member to 4.21 ± 0.35 Ga, confirming Noachian-era sedimentation and alteration processes, while a sandstone yielded a younger diagenetic age of about 3.5-4.0 Ga. These results validate the antiquity of habitable environments in Gale Crater and provide direct calibration for relative dating techniques. To scale relative crater counts to absolute time, model production functions integrate meteorite-derived ages with impact flux models. Hartmann's chronology system links crater retention ages— the time surfaces preserve craters of specific sizes—to absolute timelines, calibrated against the planet's formation at approximately 4.5 Ga and anchored by SNC meteorite dates. This framework estimates surface ages from billions of years in the southern highlands to mere millions in young volcanic plains, though it assumes a declining impact rate post-Late Heavy Bombardment. Despite these advances, absolute dating on Mars faces significant challenges, including the absence of returned samples for comprehensive lab analysis and potential alteration of isotopes by shock or weathering. The Perseverance rover addresses this by caching core samples from Jezero Crater in sealed tubes on the surface, intended for retrieval by future missions like Mars Sample Return for high-precision dating on Earth. Recent contributions from the InSight mission's heat flow probe data, though limited by partial deployment, constrain core cooling rates and support models of magnetic dynamo cessation around 4 Ga, aligning with the end of widespread crustal magnetization observed in ancient terrains.Mineralogical and Geochemical Indicators

Mineralogical and geochemical analyses provide key insights into Mars' past environmental conditions, revealing episodes of aqueous activity and atmospheric evolution through the identification of alteration products and isotopic signatures. Orbital spectroscopy instruments, such as the Observatoire pour la Minéralogie, l'Eau, les Glaces et l'Activité (OMEGA) on Mars Express and the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, have mapped widespread phyllosilicates, including smectites and serpentines, primarily in Noachian-aged terrains. These minerals form through aqueous alteration of mafic silicates under neutral to alkaline conditions, suggesting prolonged surface or near-surface water interactions during Mars' early history. In contrast, sulfates such as gypsum and kieserite dominate in Hesperian deposits, indicative of acidic, evaporative environments where water evaporated from shallow basins or lakes. Geochemical trends observed in Martian meteorites further illuminate the planet's redox evolution, transitioning from a reducing early atmosphere to more oxidizing conditions over time. Early basaltic meteorites, like the nakhlites and shergottites, exhibit high FeO content and low oxidation states, consistent with magmas formed under reducing conditions with a CO-rich atmosphere.[100] Later samples show increasing Fe2O3/FeO ratios, reflecting atmospheric oxidation and the incorporation of oxidized phases, likely driven by loss of reducing gases like H2 and CO to space.[101] These shifts correlate with stratigraphic units, providing relative timelines for environmental changes.[101] The timescales of mineral alteration offer additional constraints on the duration of habitable conditions. For instance, the transformation of olivine to serpentine via hydration requires sustained interaction with liquid water, occurring over geological timescales of approximately 100 million years under moderate temperatures and pressures inferred for early Mars.[102] In-situ investigations confirm these processes; the Opportunity rover's Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS) identified jarosite in sulfate-rich outcrops at Meridiani Planum, a potassium-iron sulfate mineral that precipitates from acidic waters with pH below 3, pointing to evaporative acidic lakes around 3.5 billion years ago. Isotopic analyses from rover missions reveal the history of water loss and atmospheric escape. The Curiosity rover's Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument measured deuterium-to-hydrogen (D/H) ratios in clay minerals from Gale Crater mudstones at approximately three times the terrestrial value, indicating that a significant fraction of Mars' original water inventory was lost to space through hydrodynamic escape and sputtering over billions of years. These elevated D/H signatures in hydrous phases preserve evidence of an early wetter atmosphere that fractionated as lighter hydrogen preferentially escaped.[103]References

- https://www.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/news-release/nasa-mission-reveals-speed-of-solar-wind-stripping-martian-atmosphere/