Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Noachian

View on Wikipedia| Noachian | |

|---|---|

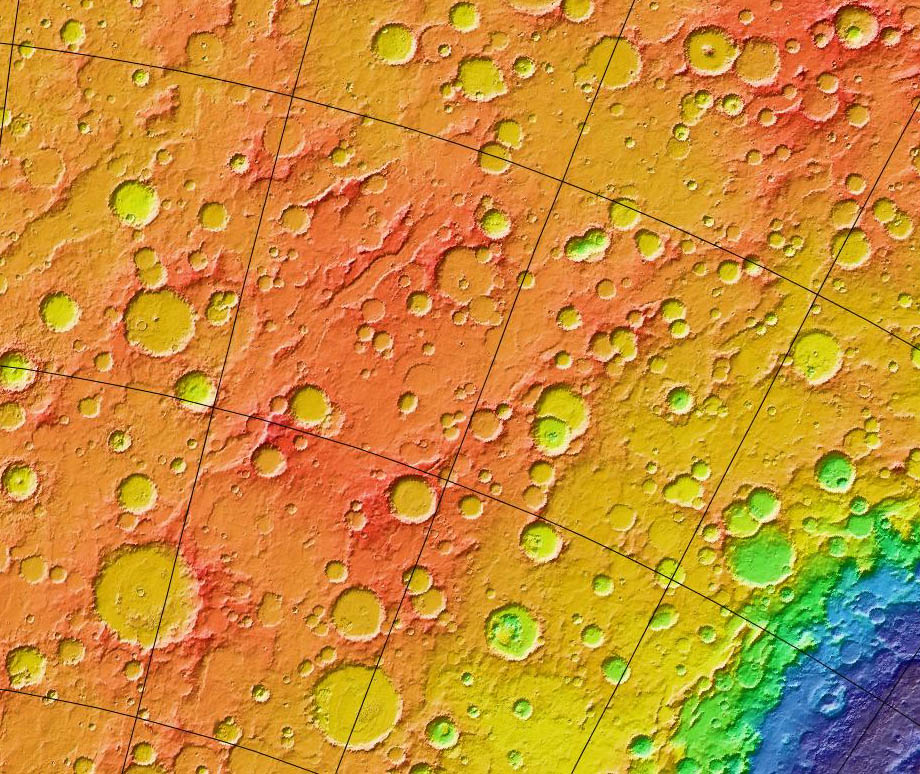

MOLA colorized relief map of Noachis Terra, the type area for the Noachian System. Note the superficial resemblance to the lunar highlands. Colors indicate elevation, with red highest and blue-violet lowest. The blue feature at bottom right is the northwestern portion of the giant Hellas impact basin. | |

| Chronology | |

| Subdivisions | Early Noachian Middle Noachian |

| Usage information | |

| Celestial body | Mars |

| Time scale(s) used | Martian Geologic Timescale |

| Definition | |

| Chronological unit | Period |

| Stratigraphic unit | System |

| Type section | Noachis Terra |

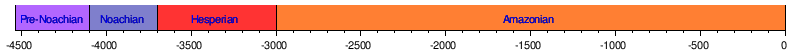

The Noachian is a geologic system and early time period on the planet Mars characterized by high rates of meteorite and asteroid impacts and the possible presence of abundant surface water.[1] The absolute age of the Noachian period is uncertain but probably corresponds to the lunar Pre-Nectarian to Early Imbrian periods[2] of 4100 to 3700 million years ago, during the interval known as the Late Heavy Bombardment.[3] Many of the large impact basins on the Moon and Mars formed at this time. The Noachian Period is roughly equivalent to the Earth's Hadean and early Archean eons when Earth's first life forms likely arose.[4]

Noachian-aged terrains on Mars are prime spacecraft landing sites to search for fossil evidence of life.[5][6][7] During the Noachian, the atmosphere of Mars was denser than it is today, and the climate possibly warm enough (at least episodically) to allow rainfall.[8] Large lakes and rivers were present in the southern hemisphere,[9][10] and an ocean may have covered the low-lying northern plains.[11][12] Extensive volcanism occurred in the Tharsis region, building up enormous masses of volcanic material (the Tharsis bulge) and releasing large quantities of gases into the atmosphere.[3] Weathering of surface rocks produced a diversity of clay minerals (phyllosilicates) that formed under chemical conditions conducive to microbial life.[13][14]

Although there is abundant geologic evidence for surface water early in Mars history, the nature and timing of the climate conditions under which that water occurred is a subject of vigorous scientific debate.[15] Today Mars is a cold, hyperarid desert with an average atmospheric pressure less than 1% that of Earth. Liquid water is unstable and will either freeze or evaporate depending on season and location (See Water on Mars). Reconciling the geologic evidence of river valleys and lakes with computer climate models of Noachian Mars has been a major challenge.[16] Models that posit a thick carbon dioxide atmosphere and consequent greenhouse effect have difficulty reproducing the higher mean temperatures necessary for abundant liquid water. This is partly because Mars receives less than half the solar radiation that Earth does and because the sun during the Noachian was only about 75% as bright as it is today.[17][18] As a consequence, some researchers now favor an overall Noachian climate that was “cold and icy” punctuated by brief (hundreds to thousands of years) climate excursions warm enough to melt surface ice and produce the fluvial features seen today.[19] Other researchers argue for a semiarid early Mars with at least transient periods of rainfall warmed by a carbon dioxide-hydrogen atmosphere.[20] Causes of the warming periods remain unclear but may be due to large impacts, volcanic eruptions, or orbital forcing. In any case it seems probable that the climate throughout the Noachian was not uniformly warm and wet.[21] In particular, much of the river- and lake-forming activity appears to have occurred over a relatively short interval at the end of the Noachian and extending into the early Hesperian.[22][23][24]

Description and name origin

[edit]The Noachian System and Period is named after Noachis Terra (lit. "Land of Noah"), a heavily cratered highland region west of the Hellas basin. The type area of the Noachian System is in the Noachis quadrangle (MC-27) around 40°S 340°W / 40°S 340°W.[2] At a large scale (>100 m), Noachian surfaces are very hilly and rugged, superficially resembling the lunar highlands. Noachian terrains consist of overlapping and interbedded ejecta blankets of many old craters. Mountainous rim materials and uplifted basement rock from large impact basins are also common.[25] (See Anseris Mons, for example.) The number-density of large impact craters is very high, with about 200 craters greater than 16 km in diameter per million km2.[26] Noachian-aged units cover 45% of the Martian surface;[27] they occur mainly in the southern highlands of the planet, but are also present over large areas in the north, such as in Tempe and Xanthe Terrae, Acheron Fossae, and around the Isidis basin (Libya Montes).[28][29]

Epochs:

Noachian chronology and stratigraphy

[edit]

Martian time periods are based on geological mapping of surface units from spacecraft images.[25][30] A surface unit is a terrain with a distinct texture, color, albedo, spectral property, or set of landforms that distinguish it from other surface units and is large enough to be shown on a map.[31] Mappers use a stratigraphic approach pioneered in the early 1960s for photogeologic studies of the Moon.[32][33] Although based on surface characteristics, a surface unit is not the surface itself or group of landforms. It is an inferred geologic unit (e.g., formation) representing a sheetlike, wedgelike, or tabular body of rock that underlies the surface.[34][35] A surface unit may be a crater ejecta deposit, lava flow, or any surface that can be represented in three dimensions as a discrete stratum bound above or below by adjacent units (illustrated right). Using principles such as superpositioning (illustrated left), cross-cutting relationships, and the relationship of impact crater density to age, geologists can place the units into a relative age sequence from oldest to youngest. Units of similar age are grouped globally into larger, time-stratigraphic (chronostratigraphic) units, called systems. For Mars, four systems are defined: the Pre-Noachian, Noachian, Hesperian, and Amazonian. Geologic units lying below (older than) the Noachian are informally designated Pre-Noachian.[36] The geologic time (geochronologic) equivalent of the Noachian System is the Noachian Period. Rock or surface units of the Noachian System were formed or deposited during the Noachian Period.

System vs. Period

[edit]| Segments of rock (strata) in chronostratigraphy | Periods of time in geochronology | Notes (Mars) |

|---|---|---|

| Eonothem | Eon | not used for Mars |

| Erathem | Era | not used for Mars |

| System | Period | 3 total; 108 to 109 years in length |

| Series | Epoch | 8 total; 107 to 108 years in length |

| Stage | Age | not used for Mars |

| Chronozone | Chron | smaller than an age/stage; not used by the ICS timescale |

System and Period are not interchangeable terms in formal stratigraphic nomenclature, although they are frequently confused in popular literature. A system is an idealized stratigraphic column based on the physical rock record of a type area (type section) correlated with rocks sections from many different locations planetwide.[38] A system is bound above and below by strata with distinctly different characteristics (on Earth, usually index fossils) that indicate dramatic (often abrupt) changes in the dominant fauna or environmental conditions. (See Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary as example.)

At any location, rock sections in a given system are apt to contain gaps (unconformities) analogous to missing pages from a book. In some places, rocks from the system are absent entirely due to nondeposition or later erosion. For example, rocks of the Cretaceous System are absent throughout much of the eastern central interior of the United States. However, the time interval of the Cretaceous (Cretaceous Period) still occurred there. Thus, a geologic period represents the time interval over which the strata of a system were deposited, including any unknown amounts of time present in gaps.[38] Periods are measured in years, determined by radioactive dating. On Mars, radiometric ages are not available except from Martian meteorites whose provenance and stratigraphic context are unknown. Instead, absolute ages on Mars are determined by impact crater density, which is heavily dependent upon models of crater formation over time.[39] Accordingly, the beginning and end dates for Martian periods are uncertain, especially for the Hesperian/Amazonian boundary, which may be in error by a factor of 2 or 3.[36][40]

Boundaries and subdivisions

[edit]Across many areas of the planet, the top of the Noachian System is overlain by more sparsely cratered, ridged plains materials interpreted to be vast flood basalts similar in makeup to the lunar maria. These ridged plains form the base of the younger Hesperian System (pictured right). The lower stratigraphic boundary of the Noachian System is not formally defined. The system was conceived originally to encompass rock units dating back to the formation of the crust 4500 million years ago.[25] However, work by Herbert Frey and colleagues at NASA's Goddard Spaceflight Center using Mars Orbital Laser Altimeter (MOLA) data indicates that the southern highlands of Mars contain numerous buried impact basins (called quasi-circular depressions, or QCDs) that are older than the visible Noachian-aged surfaces and that pre-date the Hellas impact. He suggests that the Hellas impact should mark the base of the Noachian System. If Frey is correct, then much of the bedrock in the Martian highlands is pre-Noachian in age, dating back to over 4100 million years ago.[41]

The Noachian System is subdivided into three chronostratigraphic series: Lower Noachian, Middle Noachian, and Upper Noachian. The series are based on referents or locations on the planet where surface units indicate a distinctive geological episode, recognizable in time by cratering age and stratigraphic position. For example, the referent for the Upper Noachian is an area of smooth intercrater plains east of the Argyre basin. The plains overlie (are younger than) the more rugged cratered terrain of the Middle Noachian and underlie (are older than) the less cratered, ridged plains of the Lower Hesperian Series.[2][42] The corresponding geologic time (geochronological) units of the three Noachian series are the Early Noachian, Mid Noachian, and Late Noachian Epochs. Note that an epoch is a subdivision of a period; the two terms are not synonymous in formal stratigraphy.

Stratigraphic terms are often confusing to geologists and non-geologists alike. One way to sort through the difficulty is by the following example: You can easily go to Cincinnati, Ohio and visit a rock outcrop in the Upper Ordovician Series of the Ordovician System. You can even collect a fossil trilobite there. However, you cannot visit the Late Ordovician Epoch in the Ordovician Period and collect an actual trilobite.

The Earth-based scheme of formal stratigraphic nomenclature has been successfully applied to Mars for several decades now but has numerous flaws. The scheme will no doubt become refined or replaced as more and better data become available.[43] (See mineralogical timeline below as example of alternative.) Obtaining radiometric ages on samples from identified surface units is clearly necessary for a more complete understanding of Martian history and chronology.[44]

Mars during the Noachian Period

[edit]

The Noachian Period is distinguished from later periods by high rates of impacts, erosion, valley formation, volcanic activity, and weathering of surface rocks to produce abundant phyllosilicates (clay minerals). These processes imply a wetter global climate with at least episodic warm conditions.[3]

Impact cratering

[edit]The lunar cratering record suggests that the rate of impacts in the Inner Solar System 4000 million years ago was 500 times higher than today.[45] During the Noachian, about one 100-km diameter crater formed on Mars every million years,[3] with the rate of smaller impacts exponentially higher.[a] Such high impact rates would have fractured the crust to depths of several kilometers[47] and left thick ejecta deposits across the planet's surface. Large impacts would have profoundly affected the climate by releasing huge quantities of hot ejecta that heated the atmosphere and surface to high temperatures.[48] High impact rates probably played a role in removing much of Mars's early atmosphere through impact erosion.[49]

By analogy with the Moon, frequent impacts produced a zone of fractured bedrock and breccias in the upper crust called the megaregolith.[51] The high porosity and permeability of the megaregolith permitted the deep infiltration of groundwater. Impact-generated heat reacting with the groundwater produced long-lived hydrothermal systems that could have been exploited by thermophilic microorganisms, if any existed.[52] Computer models of heat and fluid transport in the ancient Martian crust suggest that the lifetime of an impact-generated hydrothermal system could be hundreds of thousands to millions of years after impact.[53]

Erosion and valley networks

[edit]Most large Noachian craters have a worn appearance, with highly eroded rims and sediment-filled interiors. The degraded state of Noachian craters, compared with the nearly pristine appearance of Hesperian craters only a few hundred million years younger, indicates that erosion rates were higher (approximately 1000 to 100,000 times[54]) in the Noachian than in subsequent periods.[3] The presence of partially eroded (etched) terrain in the southern highlands indicates that up to 1 km of material was eroded during the Noachian Period. These high erosion rates, though still lower than average terrestrial rates, are thought to reflect wetter and perhaps warmer environmental conditions.[55]

The high erosion rates during the Noachian may have been due to precipitation and surface runoff.[8][56] Many (but not all) Noachian-aged terrains on Mars are densely dissected by valley networks.[3] Valley networks are branching systems of valleys that superficially resemble terrestrial river drainage basins. Although their principal origin (rainfall erosion, groundwater sapping, or snow melt) is still debated, valley networks are rare in subsequent Martian time periods, indicating unique climatic conditions in Noachian times.

At least two separate phases of valley network formation have been identified in the southern highlands. Valleys that formed in the Early to Mid Noachian show a dense, well-integrated pattern of tributaries that closely resemble drainage patterns formed by rainfall in desert regions of Earth. Younger valleys from the Late Noachian to Early Hesperian commonly have only a few stubby tributaries with interfluvial regions (upland areas between tributaries) that are broad and undissected. These characteristics suggest that the younger valleys were formed mainly by groundwater sapping. If this trend of changing valley morphologies with time is real, it would indicate a change in climate from a relatively wet and warm Mars, where rainfall was occasionally possible, to a colder and more arid world where rainfall was rare or absent.[57]

Lakes and oceans

[edit]

Water draining through the valley networks ponded in the low-lying interiors of craters and in the regional hollows between craters to form large lakes. Over 200 Noachian lake beds have been identified in the southern highlands, some as large as Lake Baikal or the Caspian Sea on Earth.[58] Many Noachian craters show channels entering on one side and exiting on the other. This indicates that large lakes had to be present inside the crater at least temporarily for the water to reach a high enough level to breach the opposing crater rim. Deltas or fans are commonly present where a valley enters the crater floor. Particularly striking examples occur in Eberswalde Crater, Holden Crater, and in Nili Fossae region (Jezero Crater). Other large craters (e.g., Gale Crater) show finely layered, interior deposits or mounds that probably formed from sediments deposited on lake bottoms.[3]

Much of the northern hemisphere of Mars lies about 5 km lower in elevation than the southern highlands.[59] This dichotomy has existed since the Pre-Noachian.[60] Water draining from the southern highlands during the Noachian would be expected to pool in the northern hemisphere, forming an ocean (Oceanus Borealis[61]). Unfortunately, the existence and nature of a Noachian ocean remains uncertain because subsequent geologic activity has erased much of the geomorphic evidence.[3] The traces of several possible Noachian- and Hesperian-aged shorelines have been identified along the dichotomy boundary,[62][63] but this evidence has been challenged.[64][65] Paleoshorelines mapped within Hellas Planitia, along with other geomorphic evidence, suggest that large, ice-covered lakes or a sea covered the interior of the Hellas basin during the Noachian period.[66] In 2010, researchers used the global distribution of deltas and valley networks to argue for the existence of a Noachian shoreline in the northern hemisphere.[12] Despite the paucity of geomorphic evidence, if Noachian Mars had a large inventory of water and warm conditions, as suggested by other lines of evidence, then large bodies of water would have almost certainly accumulated in regional lows such as the northern lowland basin and Hellas.[3]

Volcanism

[edit]The Noachian was also a time of intense volcanic activity, most of it centered in the Tharsis region.[3] The bulk of the Tharsis bulge is thought to have accumulated by the end of the Noachian Period.[67] The growth of Tharsis probably played a significant role in producing the planet's atmosphere and the weathering of rocks on the surface. By one estimate, the Tharsis bulge contains around 300 million km3 of igneous material. Assuming the magma that formed Tharsis contained carbon dioxide (CO2) and water vapor in percentages comparable to that observed in Hawaiian basaltic lava, then the total amount of gases released from Tharsis magmas could have produced a 1.5-bar CO2 atmosphere and a global layer of water 120 m deep.[3]

Extensive volcanism also occurred in the cratered highlands outside of the Tharsis region, but little geomorphologic evidence remains because surfaces have been intensely reworked by impact.[3] Spectral evidence from orbit indicates that highland rocks are primarily basaltic in composition, consisting of the minerals pyroxene, plagioclase feldspar, and olivine.[68] Rocks examined in the Columbia Hills by the Mars Exploration Rover (MER) Spirit may be typical of Noachian-aged highland rocks across the planet.[69] The rocks are mainly degraded basalts with a variety of textures indicating severe fracturing and brecciation from impact and alteration by hydrothermal fluids. Some of the Columbia Hills rocks may have formed from pyroclastic flows.[3]

Weathering products

[edit]The abundance of olivine in Noachian-aged rocks is significant because olivine rapidly weathers to clay minerals (phyllosilicates) when exposed to water. Therefore, the presence of olivine suggests that prolonged water erosion did not occur globally on early Mars. However, spectral and stratigraphic studies of Noachian outcroppings from orbit indicate that olivine is mostly restricted to rocks of the Upper (Late) Noachian Series.[3] In many areas of the planet (most notably Nili Fossae and Mawrth Vallis), subsequent erosion or impacts have exposed older Pre-Noachian and Lower Noachian units that are rich in phyllosilicates.[70][71] Phyllosilicates require a water-rich, alkaline environment to form. In 2006, researchers using the OMEGA instrument on the Mars Express spacecraft proposed a new Martian era called the Phyllocian, corresponding to the Pre-Noachian/Early Noachian in which surface water and aqueous weathering was common. Two subsequent eras, the Theiikian and Siderikian, were also proposed.[13] The Phyllocian era correlates with the age of early valley network formation on Mars. It is thought that deposits from this era are the best candidates in which to search for evidence of past life on the planet.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The size-distribution of Earth-crossing asteroids greater than 100 m in diameter follows an inverse power-law curve of form N = kD−2.5, where N is the number of asteroids larger than diameter D.[46] Asteroids with smaller diameters are present in much greater numbers than asteroids with large diameters.

References

[edit]- ^ Amos, Jonathan (10 September 2012). "Clays in Pacific Lavas Challenge Wet Early Mars Idea". BBC News.

- ^ a b c Tanaka, K.L. (1986). "The Stratigraphy of Mars". J. Geophys. Res. 91 (B13): E139 – E158. Bibcode:1986JGR....91E.139T. doi:10.1029/JB091iB13p0E139.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Carr, M.H.; Head, J.W. (2010). "Geologic History of Mars". Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 294 (3–4): 185–203. Bibcode:2010E&PSL.294..185C. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.06.042.

- ^ Abramov, O.; Mojzsis, S.J. (2009). "Microbial Habitability of the Hadean Earth During the Late Heavy Bombardment". Nature. 459 (7245): 419–422. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..419A. doi:10.1038/nature08015. PMID 19458721. S2CID 3304147.

- ^ Grotzinger, J (2009). "Beyond Water on Mars". Nature Geoscience. 2 (4): 231–233. Bibcode:2009NatGe...2..231G. doi:10.1038/ngeo480.

- ^ Grant, J.A.; et al. (2010). "The Science Process for Selecting the Landing Site for the 2011 Mars Science Laboratory" (PDF). Planet. Space Sci. 59 (11–12): 1114–1127. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2010.06.016.

- ^ Anderson, R.C.; Dohm, J.M.; Buczkowski, D.; Wyrick, D.Y. (2022). Early Noachian Terrains: Vestiges of the Early Evolution of Mars. Icarus, 387, 115170.

- ^ a b Craddock, R. A.; Howard, A.D. (2002). "The Case for Rainfall on a Warm, Wet Early Mars". J. Geophys. Res. 107 (E11): 5111. Bibcode:2002JGRE..107.5111C. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.485.7566. doi:10.1029/2001JE001505.

- ^ Malin, M.C.; Edgett, K.S. (2003). "Evidence for Persistent Flow and Aqueous Sedimentation on Early Mars". Science. 302 (5652): 1931–1934. Bibcode:2003Sci...302.1931M. doi:10.1126/science.1090544. PMID 14615547. S2CID 39401117.

- ^ Irwin, R.P.; et al. (2002). "A Large Paleolake Basin at the Head of Ma'adim Vallis, Mars". Science. 296 (5576): 2209–12. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.2209R. doi:10.1126/science.1071143. PMID 12077414. S2CID 23390665.

- ^ Clifford, S.M.; Parker, T.J. (2001). "The Evolution of the Martian Hydrosphere: Implications for the Fate of a Primordial Ocean and the Current State of the Northern Plains". Icarus. 154 (1): 40–79. Bibcode:2001Icar..154...40C. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6671.

- ^ a b Di Achille, G.; Hynek, B.M. (2010). "Ancient Ocean on Mars Supported by Global Distribution of Deltas and Valleys". Nature Geoscience. 3 (7): 459–463. Bibcode:2010NatGe...3..459D. doi:10.1038/NGEO891.

- ^ a b Bibring, J.-P.; et al. (2006). "Global Mineralogical and Aqueous Mars History Derived from OMEGA/Mars Express Data". Science. 312 (5772): 400–404. Bibcode:2006Sci...312..400B. doi:10.1126/science.1122659. PMID 16627738.

- ^ Bishop, J.L.; et al. (2008). "Phyllosilicate Diversity and Past Aqueous Activity Revealed at Mawrth Vallis, Mars" (PDF). Science (Submitted manuscript). 321 (5890): 830–833. Bibcode:2008Sci...321..830B. doi:10.1126/science.1159699. PMC 7007808. PMID 18687963.

- ^ Wordsworth, R. Ehlmann, B.; Forget, F.; Haberle, R.; Head, J.; Kerber, L. (2018). Healthy Debate on Early Mars (Letter to the Editor). Nature Geoscience, 11, 888.

- ^ Kite, E.S. (2019). Geologic Constraints on Early Mars Climate. Space Sci. Rev. 215(10), https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-018-0575-5.

- ^ Wordsworth, R. et al. (2013). Global Modelling of the Early Martian Climate under a Denser CO2 Atmosphere: Water Cycle and Ice Evolution. Icarus, 222, 1–19.

- ^ Gough, D. O. (1981). Solar interior structure and luminosity variations. Solar Physics, 74(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00151270.

- ^ Fastook, J. L.; Head, J. W. (2015). Glaciation in the Late Noachian Icy Highlands: Ice Accumulation, Distribution, Flow Rates, Basal Melting, and Top-Down Melting Rates and Patterns. Planetary and Space Science, 106, 82–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2014.11.028

- ^ Ramirez, R.M.; Craddock, R.A. (2018). The Geological and Climatological Case for a Warmer and Wetter Early Mars. Nature Geoscience, 11, 230–237.

- ^ Wordsworth, R. (2016). The Climate of Early Mars. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci., 44, 381–408.

- ^ Howard, A.D.; Moore, J.M.; Irwin, R.P. (2005). An Intense Terminal Epoch of Widespread Fluvial Activity on Early Mars: 1. Valley Network Incision and Associated Deposits. J. Geophys. Res., 110, E12S14, doi:10.1029/2005JE002459.

- ^ Fassett, C.I.; Head, J.W. (2008a). The Timing of Martian Valley Network Activity: Constraints from Buffered Crater Counting. Icarus, 195, 61–89.

- ^ Fassett, C.I.; Head, J.W. (2008b). Valley Network-Fed, Open-Basin Lakes on Mars: Distribution and Implications for Noachian Surface and Subsurface Hydrology. Icarus, 198, 37–56.

- ^ a b c Scott, D.H.; Carr, M.H. (1978). Geologic Map of Mars. U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Investigations Series Map I-1083.

- ^ Werner, S.C.; Tanaka, K.L. (2011). Redefinition of the Crater-Density and Absolute-Age Boundaries for the Chronostratigraphic System of Mars. Icarus, 215, 603–607.

- ^ Tanaka, K.L. et al. (2014). Geologic Map of Mars. U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3292, pamphlet

- ^ Scott, D.H.; Tanaka, K.L. (1986). Geologic Map of the Western Equatorial Region of Mars. U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Investigations Series Map I–1802–A.

- ^ Greeley, R.; Guest, J.E. (1987). Geologic Map of the Eastern Equatorial Region of Mars. U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Investigations Series Map I–1802–B.

- ^ McCord, T.M.; et al. (1980). "Definition and Characterization of Mars Global Surface Units: Preliminary Unit Maps" (PDF). 11th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Houston, Texas: 697–699.

- ^ Greeley, R. (1994) Planetary Landscapes, 2nd ed.; Chapman & Hall: New York, p. 8 and Fig. 1.6.

- ^ Mutch, T.A. (1970). Geology of the Moon: A Stratigraphic View. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 324.

- ^ Wilhelms, D.E. (1987). "The Geologic History of the Moon". USGS Professional Paper 1348.

- ^ Wilhelms, D.E. (1990). Geologic Mapping in Planetary Mapping, R. Greeley, R.M. Batson, Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge UK, p. 214.

- ^ Tanaka, K.L.; Scott, D.H.; Greeley, R. (1992). Global Stratigraphy in Mars, H.H. Kieffer et al., Eds.; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, pp. 345–382.

- ^ a b c Nimmo, F.; Tanaka, K. (2005). "Early Crustal Evolution of Mars". Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 33: 133–161. Bibcode:2005AREPS..33..133N. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.33.092203.122637.

- ^ International Commission on Stratigraphy. "International Stratigraphic Chart" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- ^ a b Eicher, D.L.; McAlester, A.L. (1980). History of the Earth; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, pp 143–146, ISBN 0-13-390047-9.

- ^ Masson, P.; Carr, M.H.; Costard, F.; Greeley, R.; Hauber, E.; Jaumann, R. (2001). "Geomorphologic Evidence for Liquid Water". Chronology and Evolution of Mars. Space Sciences Series of ISSI. Vol. 96. p. 352. Bibcode:2001cem..book..333M. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-1035-0_12. ISBN 978-90-481-5725-9.

- ^ Hartmann, W.K.; Neukum, G. (2001). Cratering Chronology and Evolution of Mars. In Chronology and Evolution of Mars, Kallenbach, R. et al. Eds., Space Science Reviews, 96: 105–164.

- ^ Frey, H.V. (2003). Buried Impact Basins and the Earliest History of Mars. Sixth International Conference on Mars, Abstract #3104. http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/sixthmars2003/pdf/3104.pdf.

- ^ Masson, P (1991). "The Martian Stratigraphy—Short Review and Perspectives". Space Science Reviews. 56 (1–2): 9–12. Bibcode:1991SSRv...56....9M. doi:10.1007/bf00178385. S2CID 121719547.

- ^ Tanaka, K.L. (2001). The Stratigraphy of Mars: What We Know, Don't Know, and Need to Do. 32nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, Abstract #1695. http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2001/pdf/1695.pdf.

- ^ Carr, 2006, p. 41.

- ^ Carr, 2006, p. 23.

- ^ Carr, 2006, p. 24.

- ^ Davis, P.A.; Golombek, M.P. (1990). "Discontinuities in the Shallow Martian Crust at Lunae, Syria, and Sinai Plana". J. Geophys. Res. 95 (B9): 14231–14248. Bibcode:1990JGR....9514231D. doi:10.1029/jb095ib09p14231.

- ^ Segura, T.L.; et al. (2002). "Environmental Effects of Large Impacts on Mars". Science. 298 (5600): 1977–1980. Bibcode:2002Sci...298.1977S. doi:10.1126/science.1073586. PMID 12471254. S2CID 12947335.

- ^ Melosh, H.J.; Vickery, A.M. (1989). "Impact Erosion of the Primordial Martian Atmosphere". Nature. 338 (6215): 487–489. Bibcode:1989Natur.338..487M. doi:10.1038/338487a0. PMID 11536608. S2CID 4285528.

- ^ Carr, 2006, p. 138, Fig. 6.23.

- ^ Squyres, S.W.; Clifford, S.M.; Kuzmin, R.O.; Zimbelman, J.R.; Costard, F.M. (1992). Ice in the Martian Regolith in Mars, H.H. Kieffer et al., Eds.; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, pp. 523–554.

- ^ Abramov, O.; Mojzsis, S.J. (2016). Thermal Effects of Impact Bombardments on Noachian Mars. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 442, 108–120.

- ^ Abramov, O.; Kring, D.A. (2005). "Impact-Induced Hydrothermal Activity on Early Mars". J. Geophys. Res. 110 (E12): E12S09. Bibcode:2005JGRE..11012S09A. doi:10.1029/2005JE002453.

- ^ Golombek, M.P.; Bridges, N.T. (2000). Climate Change on Mars Inferred from Erosion Rates at the Mars Pathfinder Landing Site. Fifth International Conference on Mars, 6057.

- ^ Andrews; Hanna, J. C.; Lewis, K. W. (2011). "Early Mars hydrology: 2. Hydrological evolution in the Noachian and Hesperian epochs". J. Geophys. Res. 116 (E2): E02007. Bibcode:2011JGRE..116.2007A. doi:10.1029/2010JE003709.

- ^ Craddock, R.A.; Maxwell, T.A. (1993). "Geomorphic Evolution of the Martian Highlands through Ancient Fluvial Processes". J. Geophys. Res. 98 (E2): 3453–3468. Bibcode:1993JGR....98.3453C. doi:10.1029/92je02508.

- ^ Harrison, K. P.; Grimm, R.E. (2005). "Groundwater-Controlled Valley Networks and the Decline of Surface Runoff on Early Mars". J. Geophys. Res. 110 (E12): E12S16. Bibcode:2005JGRE..11012S16H. doi:10.1029/2005JE002455.

- ^ Fassett, C.I.; Head, J.W. (2008). "Valley Network-Fed, Open-Basin Lakes on Mars: Distribution and Implications for Noachian Surface and Subsurface Hydrology". Icarus. 198 (1): 37–56. Bibcode:2008Icar..198...37F. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.455.713. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2008.06.016.

- ^ Carr, 2006, p. 160.

- ^ Carr, 2006, p. 78.

- ^ Baker, V. R.; Strom, R. G.; Gulick, V. C.; Kargel, J. S.; Komatsu, G. (1991). "Ancient Oceans, Ice Sheets and the Hydrological Cycle on Mars". Nature. 352 (6336): 589–594. Bibcode:1991Natur.352..589B. doi:10.1038/352589a0. S2CID 4321529.

- ^ Parker, T. J.; Saunders, R. S.; Schneeberger, D. M. (1989). "Transitional Morphology in the West Deuteronilus Mensae Region of Mars: Implications for Modification of the Lowland/Upland Boundary". Icarus. 82 (1): 111–145. Bibcode:1989Icar...82..111P. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(89)90027-4.

- ^ Fairén, A. G.; Dohm, J. M.; Baker, V. R.; de Pablo, M. A.; Ruiz, J.; Ferris, J.; Anderson, R. M. (2003). "Episodic flood inundations of the northern plains of Mars" (PDF). Icarus. 165 (1): 53–67. Bibcode:2003Icar..165...53F. doi:10.1016/s0019-1035(03)00144-1.

- ^ Malin, M.; Edgett, K. (1999). "Oceans or Seas in the Martian Northern Lowlands: High Resolution Imaging Tests of Proposed Coastlines". Geophys. Res. Lett. 26 (19): 3049–3052. Bibcode:1999GeoRL..26.3049M. doi:10.1029/1999gl002342.

- ^ Ghatan, G. J.; Zimbelman, J. R. (2006). "Paucity of Candidate Coastal Constructional Landforms Along Proposed Shorelines on Mars: Implications for a Northern Lowlands-Filling Ocean". Icarus. 185 (1): 171–196. Bibcode:2006Icar..185..171G. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.007.

- ^ Moore, J.M.; Wilhelms, D.E. (2001). "Hellas as a Possible Site of Ancient Ice-Covered Lakes on Mars". Icarus. 154 (2): 258–276. Bibcode:2001Icar..154..258M. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6736. hdl:2060/20020050249.

- ^ Phillips, R.J.; et al. (2001). "Ancient Geodynamics and Global-Scale Hydrology on Mars". Science. 291 (5513): 2587–2591. Bibcode:2001Sci...291.2587P. doi:10.1126/science.1058701. PMID 11283367. S2CID 36779757.

- ^ Mustard, J.F.; et al. (2005). "Olivine and Pyroxene Diversity in the Crust of Mars". Science. 307 (5715): 1594–1597. Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1594M. doi:10.1126/science.1109098. PMID 15718427. S2CID 15548016.

- ^ Carr, 2006, p. 16-17.

- ^ Carter J.; Poulet F.; Ody A.; Bibring J.-P.; Murchie S. (2011). Global Distribution, Composition and Setting of Hydrous Minerals on Mars: A Reappraisal. 42nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, LPI: Houston, TX, abstract #2593. http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2011/pdf/2593.pdf.

- ^ Rogers, A. D.; Fergason, R.L. (2011). "Regional-Scale Stratigraphy of Surface Units in Tyrrhena and Iapygia Terrae, Mars: Insights into Highland Crustal Evolution and Alteration History". J. Geophys. Res. 116 (E8): E08005. Bibcode:2011JGRE..116.8005R. doi:10.1029/2010JE003772.

- Bibliography

- Carr, Michael, H. (2006). The Surface of Mars; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, ISBN 978-0-521-87201-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Boyce, Joseph, M. (2008). The Smithsonian Book of Mars; Konecky & Konecky: Old Saybrook, CT, ISBN 978-1-58834-074-0

- Hartmann, William, K. (2003). A Traveler’s Guide to Mars: The Mysterious Landscapes of the Red Planet; Workman: New York, ISBN 0-7611-2606-6.

- Morton, Oliver (2003). Mapping Mars: Science, Imagination, and the Birth of a World; Picador: New York, ISBN 0-312-42261-X.