Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bucharest Metro

View on Wikipedia

The Bucharest Metro (Romanian: Metroul din București) is an underground rapid transit system that serves Bucharest, the capital of Romania. It first opened for service on 16 November 1979.[5] The network is run by Metrorex. One of two parts of the larger Bucharest public transport network, Metrorex had an annual ridership of 142,783,000 passengers during 2023,[4] compared to over a billion annual passengers on Bucharest's STB transit system.[6] In total, the Metrorex system is 80.1 kilometres (49.8 mi) long and has 64 stations.[7]

| Transport in Romania |

|---|

| Companies |

The Bucharest Metro has five lines (M1, M2, M3, M4, and M5). The newest metro line, M5, was opened in 2020.[8] A sixth metro line, M6 line, is currently under construction.

As of 2024, Bucharest Metro is the only metro system in Romania; with a second one, the Cluj-Napoca Metro, being under construction.

Overview

[edit]Bucharest Metro is part of the Bucharest public transport network which also includes STB, which operates a complex network of buses, trolleybuses, light rail and trams. STB is Bucharest's surface public network system, while Bucharest Metro operates underground (a short stretch between Dimitrie Leonida and Tudor Arghezi metro stations is the only portion of the Bucharest Metro that does not run underground). Until relatively recently, car ownership in Romania was not common: during the first part of the 20th century few people had cars, and the subsequent communist regime installed after World War II restricted personal car use. The public transportation system in Bucharest has its origin in the 19th century, with the city introducing horse-drawn trams in 1872.[9]

History

[edit]

The first proposals for a metro system in Bucharest were made in the early part of the 20th century, by the Romanian engineers Dimitrie Leonida and Elie Radu.[10]

The earliest plans for a Bucharest Metro were drafted in the late 1930s, alongside the general plans for urban modernization of the city.[11] The outbreak of World War II, followed by periods of political tensions culminating with the installation of communism, put an end to the plans.[12]

By 1970, the public transport system (ITB) was no longer adequate due to the fast pace of urban development, although the system was the fourth-largest in Europe. A commission was set up, and its conclusion pointed to the necessity of an underground transit system that would become the Bucharest Metro. The plan for the first line was approved on 25 November 1974 as part of the next five-year plan and the construction on the new metro system started on 20 September 1975.[13]

The network was not built in the same style as other Eastern European systems.[10] Firstly, the design of the stations on the initial lines was simple, clean-cut modern, with most stations being relatively austere, without excessive additions such as mosaics, awkward lighting sources or elaborate and ornate decoration. The main function of the stations was speed of transit and practicality. Secondly, the trainsets themselves were all constructed in Romania and did not follow the Eastern European style of construction.[14] Each station usually followed a colour theme (generally white – in Unirii 2 (Union 2), Victoriei 1 (Victory 1), Lujerului; but also light blue – in Obor, Universitate (University), and Gara de Nord (North Train Station); orange – in Tineretului (Of Youth Station); green – in Grozăvești), and an open plan. No station was made to look exactly like any other. Despite this, many stations are rather dark, due to the policies of energy economy in the late 1980s, with later modernisations doing little to fix this problem.

During the 1980s, the metro network expanded very rapidly, at a rate only surpassed by that of the Mexico City Metro.[15] Two more lines were opened during this decade, M3 in 1983, and M2 in 1986. After the 1989 Romanian Revolution, the socioeconomic and political turmoil of the 1990s largely stagnated the expansion of the metro. Advancement of the construction was difficult; for example, the Gorjului metro station was built in two stages (1994 outbound platform and 1998 inbound platform), and as a consequence the two platforms and associated vestibules were built with different materials and with different colour schemes. The fourth metro line, M4, for which construction was started in September 1989 (shortly before the Revolution), was finally opened in 2000. After Romania joined the European Union in 2007, EU funds helped with the expansion of the metro.[16] The M5 line was opened in 2020, and the M6 line is under construction.

Due to Bucharest being one of the largest cities in the region, the network is larger than those of Prague, Warsaw, Budapest or Sofia. Bucharest Metro is also larger than some other metro systems within the European Union, such as: Rome Metro, Copenhagen Metro, Helsinki Metro, Amsterdam Metro, Brussels Metro, and Lisbon Metro. In addition, there are plans to extend the existing lines and to open two more lines: M7 and M8.[7][17] Bucharest Metro opened in 1979 (line M1), shortly after Brussels Metro (1976), Vienna U-Bahn (1976) and Amsterdam Metro (1977), and before Helsinki Metro (1982) or Copenhagen Metro (2002).

The first line, M1, opened on 19 November 1979, running from Semănătoarea (now Petrache Poenaru) to Timpuri Noi.[5] It had a length of 8.1 kilometres (5.0 mi) with 6 stations.[5] Following this, more lines and several extensions were opened:[14][18]

- 28 December 1981: M1 Timpuri Noi – Republica; 9.2 kilometres (5.7 mi), 6 stations

- 19 August 1983: M1 (now M3) Branch line Eroilor – Industriilor (now Preciziei) ; 8.2 kilometres (5.1 mi), 4 stations (Gorjului added later)

- 22 December 1984: M1 Semănătoarea (Petrache Poenaru) – Crângași; 0.97 kilometres (0.60 mi), 1 station

- 24 January 1986: M2 Piața Unirii (Union Square) – Depoul IMGB (now Berceni) ; 9.96 kilometres (6.19 mi), 6 stations (Tineretului and Constantin Brâncoveanu added later)

- 6 April 1986: M2 Tineretului; 1 infill station

- 24 October 1987: M2 Piața Unirii (Union Square) – Pipera; 8.72 kilometres (5.42 mi), 5 stations (Piața Romană = Roman Square, added later)

- 24 December 1987: M1 Crângași – Gara de Nord 1 (North Train Station 1); 2.83 kilometres (1.76 mi), 1 station (Basarab added later)

- 28 November 1988: M2 Piața Romană (Roman Square); 1 infill station

- 5 December 1988: M2 Constantin Brâncoveanu; 1 infill station

- 17 August 1989: M3 (now M1) Gara de Nord 1 (North Train Station 1) – Dristor 2; 7.8 kilometres (4.8 mi), 6 stations

- May 1991: M1 Republica – Pantelimon; 1.43 kilometres (0.89 mi), 1 station (single track, operational on a special schedule)

- 26 August 1992: M1 Basarab; 1 infill station

- 31 August 1994: M3 Gorjului; 1 infill station (westbound platform only; eastbound platform opened in 1998)

- 1 March 2000: M4 Gara de Nord 2 (North Train Station 2) – 1 Mai (First of May); 3.6 kilometres (2.2 mi), 4 stations

- 20 November 2008: M3 branch Nicolae (Nicolas) Grigorescu 2 – Linia de Centură (now Anghel Saligny), 4.75 kilometres (2.95 mi), 4 stations

- 1 July 2011: M4 1 Mai – Parc Bazilescu, 2.62 kilometres (1.63 mi), 2 stations

- 31 March 2017: M4 Parc Bazilescu – Străulești, 1.89 kilometres (1.17 mi), 2 stations[19]

- 15 September 2020: M5 Râul Doamnei / Valea Ialomiței – Eroilor 2 6.87 kilometres (4.27 mi), 10 stations[20]

- 15 November 2023: M2 Berceni – Tudor Arghezi, 1,6 kilometers (1 mi.), 1 station[21]

Expansions in the near future (estimative):

- 2027: M6 1 Mai (First of May) - Tokyo, 6.6 kilometres (4.1 mi), 6 stations[22]

- 2028: M6 Tokyo - Otopeni Airport, 7.6 kilometres (4.7 mi), 6 stations[23]

- 2030: M5 Eroilor 2 - Piața Iancului (Iancu's Square) 2, 5,4 kilometers (2 mi.), 6 stations

Lines M1 and M3 have been sharing the section between Eroilor and Nicolae Grigorescu.

Lines M5 have been sharing the section between Romancerilor.

Lines M4 and M6 have been sharing the section between Gara de Nord 2 and 1 Mai.

The newest metro station, Tudor Arghezi (M2), was opened on 15 November 2023. Between that date and 8 May 2024,[24] all services to Tudor Arghezi ran in a shuttle service from Berceni, because the signalling and automatisation systems were not yet finished.[25]

Large stations which connect with other lines, such as Piața Victoriei, have two terminals, and each terminal goes by a different name (Victoriei 1 and Victoriei 2). On the official network map, they are shown as two stations with a connection in between, even though, in fact – and for trip planners – they are a single station with platforms at different levels. There is one exception: Gara de Nord 1 and Gara de Nord 2 are separate stations (although linked through a subterranean passage, the traveller is required to exit the station proper and pay for a new fare at the other station, thus leaving the system), passengers being required to change trains at Basarab.

Generally, the underground stations feature large interiors.[13] The largest one, Piata Unirii, is cathedral-like, with vast interior spaces, hosting retail outlets and fast-food restaurants and has an intricate network of underground corridors and passageways.

Metrorex

[edit]Metrorex is the Romanian company which runs the Bucharest Metro. It is fully owned by the Romanian Government through the Ministry of Transportation.[26][27] There were plans to merge the underground and overground transportation systems into one authority subordinated to the City of Bucharest, however these plans did not come to fruition.

Infrastructure and network

[edit]

As of 2023, the entire network runs underground, except for a stretch between Dimitrie Leonida and Tudor Arghezi stations on the southern end of the M2 line. All metro stations are underground, except two (Berceni and Tudor Arghezi, which are the former terminus and current terminus, respectively, of line M2). The network is served by six depots, two being located above ground (IMGB and Industriilor) and four underground (Ciurel, Străulești, Pantelimon and Valea Ialomiței) and smaller additional works at Gara de Nord 1, Eroilor 1, Republica, Parc Drumul Taberei, Favorit, Anghel Saligny, Crângași, Piața Victoriei 2 and Dristor 2 stations.

There are two connections between the Metro network and the Romanian Railways network, one at Berceni (connecting to the Bucharest Belt Ring), the other at Ciurel (connecting via an underground passage to the Cotroceni-Militari industrial railway). However, the latter connection is currently unused and mothballed. The metro network and the national rail network have almost similar track gauge (using the 1,432 mm / 4 ft 8+3⁄8 in vs 1,435 mm / 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) and loading gauge but not the same electrification system (the metro uses 750 V DC third rail[a] whereas the Romanian Railways use 25 kV 50 Hz AC overhead lines) making it possible for new metro cars to be transported cross country as unpowered railway cars. This distinction is also seen in the pre-2007 separation between the MTR and the former KCR network in Hong Kong (see Track gauge in Hong Kong).

Lines

[edit]There are five metro lines in operation and another one in the construction phase:

| Line | Opened | Last expansion |

Track length[3][28] | Headway[1] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| operational | under construction | planned | off-peak | rush hour | |||

| M1 | November 1979 |

August 1992 |

31.01 km | — | — | 9–12 minutes (between Dristor 2 and Eroilor) (4 minutes between Eroilor and Nicolae Grigorescu) |

3–6 minutes (3–3.5 minutes between Eroilor and Nicolae Grigorescu) |

| M2 | January 1986 |

November 2023 | 20.28 km | — | 3.0 km | 4–7 minutes (weekdays off peak hours) 7–9 minutes (weekends, late nights) |

1–3 minutes |

| M3 | August 1983 |

November 2008 |

13.53 km + 8.67 km (M1) |

— | — | 7–9 minutes (4 minutes between Eroilor and Nicolae Grigorescu) |

3–6 minutes (3–3.5 minutes between Eroilor and Nicolae Grigorescu) |

| M4 | March 2000 |

March 2017 |

7.44 km | — | 10.6 km | 8–10 minutes | 7 minutes |

| M5 | September 2020 |

— | 6.87 km | — | 9.2 km | 18 minutes (on each branch) 9 minutes (between Eroilor and Romancierilor) |

12 minutes (on each branch) 6 minutes (between Eroilor and Romancierilor) |

| M6 | 2027–2028 | — | — | 6.6 km | 14.2 km | — | |

| Total | 79.13 km | 6.6 km | 35.6 km | ||||

- M1 Line: between Dristor and Pantelimon – the first line to open in 1979, last extension in 1990; it is circular with a North-Eastern spur. Part of its tracks are shared with M3 (7 stations).

- M2 Line: between Pipera and Tudor Arghezi. opened in 1986, last extension opened in November 2023; it runs in a north–south direction, crossing the center.

- M3 Line: between Preciziei and Anghel Saligny opened in 1983, last extension in 2008; it runs in an east–west direction, south of the center. Shares part of its tracks with M1 (7 stations).

- M4 Line: between Gara de Nord and Străulești opened in 2000, last extension was opened in 2017. Part of its tracks will be shared with M6 (4 stations).

- M5 Line: between Râul Doamnei and Eroilor opened in 2020; it runs through the Drumul Taberei neighborhood.[29]

- M6 Line: between Gara de Nord and Henri Coandă Airport. This line is bound to be opened partially from 2026. Part of its tracks will be shared with M4 (Gara de Nord - 1 Mai).

Signalling system

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2022) |

There are multiple signalling systems used. Line 2, the first one that has been modernized, uses Bombardier's CITYFLO 350 automatic train control system. It ensures the protection (ATP) and operation (ATO) of the new Bombardier Movia trains.

The system uses an IPU (Interlocking processing unit), TI21-M track circuits and EbiScreen workstations. Signals have been kept only in areas where points are present, meaning that the route has been assigned and the driver can use cab signalling. Trains are usually operated automatically, with the driver only opening and closing the doors and supervising the operation. Other features include auto turnback and a balise system, called PSM (precision stop marker). This ensures that the train can stop at the platform automatically.

On line 3, the ATC system has been merged with the Indusi system. Signals are present in point areas and platform ends. Along with the three red-yellow-green lights, the white ATP light has been added. Optical routes can be assigned, meaning that a train gets a green light (permission to pass the signal) only after the next signal has been passed by the train ahead, or a yellow light, meaning that the signal can be passed at low speed. Automatic block signals have been removed.

Line 4 uses Siemens's TBS 100 FB ATC system.

Line 5 uses Alstom's Urbalis 400 Communications-based train control system.[30]

Hours of operation

[edit]Trains run from 5 AM to 11 PM every day. The last trains on M1, M2 and M3 wait for the transfer of the passengers between lines to complete, before leaving Piața Unirii station.[31]

Headway

[edit]At rush hour, trains run at 4–6-minute intervals on lines 1 and 3, at 1-3 minute intervals on line 2, and at 7–8-minute on line 4; during the rest of the day, trains run at 8-minute intervals on lines 1 and 3, at 7-9 minute intervals on line 2 and at 10-minute intervals on line 4.[1]

Fares and tickets

[edit]

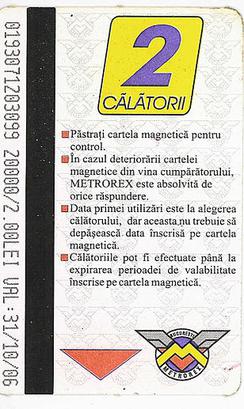

Public transport in Bucharest is heavily subsidized, and the subsidies will increase, as the City Council wants to reduce traffic jams, pollution and parking problems and promote public transport.[citation needed] Like the STB, the metro can get crowded during morning and evening rush hours. The network uses magnetic stripe cards, that are not valid for use on trams, buses or trolleybuses. Payment by contactless credit cards is available directly at the turnstiles. One tap will take 3 RON, the equivalent of one trip. For multiple validations with the same card, tap the plus button. Starting from 29 July 2021 Metrorex began replacing the magnetic stripe cards with contactless ones for weekly and monthly passes.[32] As of November 2021 most of the cards with have been replaced with contactless ones.

Tickets

[edit]

Tickets can be bought from any metro station, from both kiosks and vending machines. Prices:[33]

Metrorex only tickets:

- 1-trip card – 5 RON

- 2-trip card – 10 RON(€2.00)

- 24 hour card – 12 RON (€2.40)

- 72 hour card – 35 RON

- 10-trip card – 40 RON

- Weekly pass (full price) – 45 RON

- Monthly pass (full price) – 100 RON

- Six months pass – 500 RON

- Yearly pass – 900 RON

- Student monthly pass (available for students in Romanian Schools, High-Schools and Universities) – 10 RON

- Blood donors monthly pass – 50 RON

Integrated Metro and STB Passes:

- 1 trip card valid for 120 minutes – 5 RON

- 2 trip card valid for 120 minutes – 10 RON

- 10 trip card valid for 120 minutes – 45 RON

- 24 hour card – 14 RON

- 72 hour card – 35 RON

- 7 days card – 35 RON

- Weekly pass – 50 RON

- Monthly pass – 140 RON

- Six month pass – 700 RON

- Yearly pass – 1200 RON

Integrated Metro, STB and train on the section between North Station and Bucharest Airport:

- 24 hour card - 20 RON

- 72 hour card - 40 RON

- Monthly pass - 210 RON

- Six month pass - 1100 RON

- Yearly pass - 2000 RON

Standard trip cards are sold as anonymous magnetic strip cards, whereas the passes are sold as either MIFARE Ultralight or MIFARE Classic 1000 cards. Passengers can also opt to pay for the trip directly at the gates using credit cards or with Apple Pay/Google Pay. This payment system was implemented in 2019 with VISA, BCR and S&T Romania.

Future service

[edit]Under construction

[edit]- M6 Line: between Gara de Nord and Henri Coandă International Airport.[3] The contract for the first part of the line, known as M6.1 between 1 Mai and Tokyo has been signed in 2022 with the Turkish company Alsim Alarko. They are tasked with designing and building the structural support of the stations and tunnels. The designing and construction contract for the second half to the Henri Coandă International Airport was signed in May 2023 with the Gülermak – Somet association.[34]

Planned

[edit]- M2 Line: a further northbound extension of 1.6 km (0.99 mi) and two more stations from Pipera;[35]

- M4 Line extension: between Gara de Nord, through Soseaua Giurgiului and ending at Gara Progresul at Bucharest' southern limit. The tender for the designing and building of this extension was launched on 26 April 2024.[36]

- M5 Line: a further extension of 9.2 km (5.7 mi) to Pantelimon is approved;.[37] The central part of M5, known as M5.2, is currently designed by Metrans Engineering and 3TI Progetti SpA.

These projects are financed by the EU, with the exception of M6.2 which is financed by a loan from JICA.

Other proposals

[edit]Metrorex is also planning the following new lines, routes and stations:

- M2 Line: a further southbound extension of 3 km (1.9 mi) and three more stations from Tudor Arghezi[38]

- Line M7; it is supposed to run 25 kilometres (16 mi) from Bragadiru to Voluntari.[39]

- Line M8, the south half ring. Its route has not been fully planned yet, but it will run through Piața Sudului and end at Crângași and Dristor stations.[40]

- An extension of the Line M3 is also planned for 2030.[41]

- Two more stations are planned and may be constructed on existing lines, both on M1. However, given the complexity of work required, and the limited benefits these stations would have it is unlikely that construction will begin in the near future:

- Dorobanți between Stefan cel Mare and Piața Victoriei;

- Giulești between Crângași and Basarab.

Rolling stock

[edit]The Bucharest Metro uses three types of trainsets:[1][42]

- Astra IVA (BM1) – 84 trainsets (504 cars), built between 1976 and 1992. Only 15 trainsets (90 cars) are still operating. Until now, 69 trainsets (414 cars) have been retired from service. The remaining of 15 trainsets which are still active were refurbished by Metrorex and Alstom Transport România in 2011–2013.[3] In the past, they were used on M1, M2, M3 and M4. Presently, they are still used on M4 and occasionally on M3.

- Bombardier Movia 346 (BM2, BM21) – 44 trainsets (264 cars), built between 2002 and 2008, used on M1, M2, M3 and M5 (a modification of the Swedish SL C20 metro train type)

- CAF Inneo (BM3) – 24 trainsets (144 cars), built between 2013 and 2016, used on M2.

- Alstom Metropolis (BM4) - 13 trainsets built in Taubaté between 2023 and 2025, will be used on M5 when they will finish testing.

| Vehicle | Type and description | Interior |

|---|---|---|

|

The Romanian designed Astra IVA trains, built in Arad, are made up of various trainsets (rame) connected together. Each trainset is made up of two permanently connected train-cars (B′B′+B′B′ formation) that can only be run together. The Astra IVA rolling stock is approaching the end of its service life, so it is gradually being phased out. They are used on the Bucharest Metro Lines M3 (only on weekdays due to lack of available Bombardier trainsets) and M4. |

|

|

The Bombardier Movia 346 trains, a modification of the SL C20 type used in Sweden, are made up of six permanently connected cars, forming an open corridor for the entire length of the train (2′2′+Bo′Bo′+Bo′Bo′+Bo′Bo′+Bo′Bo′+2′2′ formation). Bombardier trains are used on all lines, except line M4. These trains were built in two series: the first 18 trains (BM2) and the last 26 trains (BM21). BM21 trains have some improvements compared to BM2 trains. These trains have electronic displays at the end of the rail cars and more grab bars. |

|

|

In November 2011, Metrorex signed a €97 million contract with CAF for 16 metro trains (96 cars), with options for a further 8 sets (48 cars).[43] The 114m-long six-car trains will be assembled in Romania. They each accommodate up to 1,200 passengers and are made up of four powered and two trailer vehicles. As of November 2014, all trains have been delivered and all 16 of them entered in service. As the CAF trains enter service, all of the Bombardier stock will be moved for use on line M3, according to Metrorex's plans to replace all of the old Astra IVA stock on the entire network.

In November 2014, Metrorex signed an additional €47 million contract with CAF for 8 metro trains. As of 2018, 24 CAF trains are in use, exclusively on line M2. |

|

|

In November 2020, Metrorex signed a €100 million contract with Alstom for 13 metro trains (78 cars), with options for a further 17 sets (102 cars).[44] The trains are to be used on the line M5. The new Alstom Metropolis BM4 will be part of the Alstom Metropolis family.

As of April 2024, the first train has arrived and is yet to complete testing. |

The subway livery for Bucharest is either white with two yellow or red horizontal stripes below the window for the Astra trains, stainless steel with black and white for the Bombardier trains, or stainless steel with blue and white for the CAF trains.

All trains run on a bottom-contact 750 V DC third rail, or an overhead wire (in maintenance areas where a third rail would not be safe). Maximum speed on the system is 80 km/h (50 mph), although plans are to increase it to 100 km/h (62 mph) on M5, a new line that opened its first phase on 15 September 2020.[45] New trains from Alstom (Metropolis) have been ordered, the first train having arrived in April 2024.[46]

Incidents

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2022) |

In its 45 years of operations, there have never been any very grave accidents, however, there have been various incidents, either during construction or operation. Accidents are investigated by the Railway Investigation Authority (Agenția de Investigare Feroviară Română (AGIFER)).

- 1983: Due to works on M2, the Piața Unirii 1 station was flooded by the Dâmbovița.

- April–May 1986: Whilst digging for a connection service tunnel for the M1-M2 lines, the foundations and altar of the Slobozia Church were cracked, leading to the subsequent closure of the construction site of the tunnel, which was filled with sand. Thus, trains for the M2 were disconnected from the rest of the network up to 1987 (trains were sent through the Bucharest Freight Railway Bypass), when another link tunnel was created at Piața Victoriei.

- 1 May 1987: During reconstruction work at Piața Unirii, the Dâmbovița was breached again, this time flooding both stations and forcing train circulation to cease for the next 5 days as a result. The flooding took place during a heavy rainstorm and during work on the Unirii Underpass (which was opened on 6 June 1987, after a record 34 days of work), when an excavator damaged a collecting canal of the Dâmbovița, flooding the underpass construction site, and subsequently, the M1 station. The M2 metro station was flooded due to an improperly sealed tube, designed for electric installations. At its peak, the flooding was 30 centimeters over the platforms, but further damages to the electrical transformers were avoided.

- 2 May 1987: During recovery from the flooding at Piața Unirii the previous day, the tunnel between Timpuri Noi and Mihai Bravu was found fully submerged by the Dâmbovița, possibly in relation to the previous incident. Signalling and other electrical cables were damaged, which further prolonged the repair efforts for the previous incident.

- 4 March 1996: The metro workers began a strike, demanding a 48% pay increase to offset inflation and better working conditions. It continued for at least 2 days, and was condemned by the Văcăroiu government as illegal.[47]

- 17 November 2010: An IVA train derailed between Timpuri Noi and Piața Unirii.

- 14 January 2015: Due to a broken pipe, a fire started out at Tineretului station, leading to its closure for the rest of the day.

- 14 June 2016: Piața Victoriei was closed after huge amounts of smoke originated from the third rail.

- 20 January 2017: A fire, originating from electrical contactors, led to the evacuation of the Universitate station, subsequently leading to the closure of one of the tracks towards Piața Unirii.

- 16 August 2018: A train in Piața Unirii had to be evacuated, after someone began pepper-spraying the consist stopped in the station.

- 26 January 2019: A newly purchased CAF unit crashed in the Berceni depot. The train, which was stabled outside, was being shunted into the depot to prevent icing, however, due to software failure, it could not stop on time and crashed past the buffers. It is likely that the train could be scrapped since there is no way to remove it.

- 26 March 2021: A sudden strike, launched by the union of the metro employees began at 5 AM, effectively blocking the circulation of all trains. The dispute is related to the activity of commercial spaces within metro stations.[48]

- 24 May 2022: 172 people were evacuated after a metro train that left from Piaţa Romană station heading to Berceni broke down.[49]

Aside from these incidents, there have been other disruptions due to suicides at the metro. A recent one on 25 June 2019, led to the disruption of metro traffic at rush hour between Piața Unirii and Eroilor (the suicide took place at Izvor). Aside from that, in 2017, one woman was arrested for pushing a person in front of a train. These incidents led to criticism of METROREX, and suggestions to install platform screen doors or to increase security. Additionally, railfans reported harassment from security guards, being told "not to photograph in the stations".

Currently, the Bucharest Metro does not use platform screen doors. Debates about the opportunity of using platform screen doors have been going on for years, and testing of such doors has been taking place at Berceni metro station,[50] but in 2024 authorities stated that it is uncertain whether platform screen doors will be installed, given concerns about financing and costs and benefits.[51] Since all the stations of Bucharest Metro were inaugurated without having platform screen doors, installing such doors would require retrofitting, namely the process of installing platform screen doors on a system that was not initially designed to accommodate such doors, which may be complex and difficult,[52] especially if the type installed were to be full-height doors (rather than half-height doors or rope-doors which are more common in retrofitting, but have limited benefits compared to full height doors).

Miscellaneous

[edit]Bucharest Metro was the only one in the world that operated with passengers during testing.[53]

In the 1980s, the speed of building the network (4 kilometers / year) placed the Bucharest Metro on the second place in the world, after Mexico City Metro.[15]

The shortest distance between two adjacent stations is between Gara de Nord 2 (M4) and Basarab 2 (M4) and is 430 meters.

Network map

[edit]See also

[edit]Note

[edit]- ^ Overhead lines with same voltage employed only in works, depots and selected tunnels.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Metrorex – Network features". Metrorex. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Lucrări începute la stația supraterană pe magistrala de metrou M2 în Berceni". 18 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Reţeaua de metrou în funcţiune (2018). Detalii M1, M2, M3, M4 la pg.6 și M5 la pg.46" (PDF). Metrorex.ro. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ a b https://www.metrorex.ro/storage/documents/1720090135Raport%20de%20activitate%202023%20Metrorex%20S.A..pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b c d "Metrorex – Metrorex history". Metrorex. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ Matei, Diana (21 March 2024). "Număr record de călătorii înregistrate de STB într-un an: peste 1 miliard. Creştere semnificativă de la 2022, la 2023".

- ^ a b "Metroul București". Metroul București.

- ^ "Linia M5 Râul Doamnei - Eroilor".

- ^ "28 decembrie 1872, pe străzile bucureștene apărea primul tramvai tras de cai | Agenția de presă Rador". 28 December 2022.

- ^ a b "30 de ani de exploatare a metroului bucurestean" (in Romanian). agir.ro. August 2009.

- ^ "Metroul bucureștean, 10 lucruri pe care ar trebui să le cunoști" (in Romanian). historia.ro. Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Bucureștiul mileniului trei imaginat în 1930" (in Romanian). cotidianul.ro. 17 October 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Ce nu știați despre metroul bucureștean: De la planurile din 1909, la Magistrala 7" (in Romanian). 19 November 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ a b Bucharest Metro at urbanrail.net

- ^ a b Juncu, Diana. "10 lucruri pe care nu le știai despre metroul bucureștean". OBSERVATOR.TV. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ^ "Finanțări europene: A fost deschisă Magistrala 5 de metrou". Ministerul Investițiilor și Proiectelor Europene (in Romanian). Retrieved 28 May 2025.

- ^ "Ce linii noi de metrou vom avea in Bucuresti". 18 October 2023.

- ^ "Istoric Metroul bucureștean" (in Romanian). metroubucuresti.webs.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Metrorex a deschis circulatia in statiile de metrou Laminorului si Straulesti" [Metrorex opened circulation in the Laminorului and Straulesti metro stations] (Press release) (in Romanian). Metrorex S.A. 31 March 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^

- 13 December 2022: M2 Tudor Arghezi, 1.6 kilometres (0.99 mi), 1 station "Linia de Metrou Magistrala 5" [Metro Line M5]. metrorexm5.ro (in Romanian). Metrorex S.A. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ "FOTO Stația de metrou "Tudor Arghezi" a fost deschisă circulației". euronews.ro: Știri de ultimă oră, breaking news, #AllViews (in Romanian). Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ "Din ce an se va ajunge cu metroul la Aeroport Otopeni". Club Feroviar (in Romanian). 2 May 2023.

- ^ "Guvernul legiferează recepția pe bucăți la Metrorex, colac de salvare pentru M6". 28 February 2024.

- ^ "În sfârșit, se va circula fără transbordare între stațiile de metrou Pipera și Tudor Arghezi". Club Feroviar (in Romanian). 8 May 2024.

- ^ Dascălu, Bogdan (15 November 2023). "FOTO Stația de metrou Tudor Arghezi a fost inaugurată fără a avea funcţional sistemul de semnalizare şi automatizare / Ce spun specialiștii despre contribuția la fluidizarea traficului". G4Media.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ "Obiective investitii - Metrou". www.mt.ro. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ "METROREX". www.metrorex.ro. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ "Magistrala 5: Secțiunea Râul Doamnei – Eroilor (PS Opera) inclusiv Valea Ialomiței (6,871 Km)". Metrorex S.A. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Metroul din Drumul Taberei. Magistrala M5 se deschide marţi, 15 septembrie. Se va inaugura cea mai modernă linie de metrou din Bucureşti". Mediafax.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "Alstom salutes the opening of the Bucharest Metro Line 5".

- ^ "Metrorex – Schedule". Metrorex. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ "Metrorex introduce propriul card contactless pentru abonamentul săptămânal, lunar sau anual". digi24.ro (in Romanian). 28 July 2021. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Metrorex – Fees". Metrorex. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ "Metroul M6 de la Băneasa la Aeroportul Otopeni: Contract de 1,27 MLD. Lei semnat cu turcii de la Gulermak / Cât ar urma să dureze construcția și ce critici puternice au avut experții externi față de proiect". hotnews.ro. 2 May 2023.

- ^ "MT va solicita finantare UE pentru Magistrala Berceni-Pipera". 17 May 2018.

- ^ "BREAKING S-a lansat licitația pentru extinderea Magistralei 4 de metrou, până la Gara Progresul". 26 April 2024.

- ^ "In ce stadiu este proiectul metroului pana la Pantelimon si cand ar putea fi gata?". Wall-Street. 10 January 2019.

- ^ "Extinderea M2 către Berceni, cu traseu și stații în câmp, i-a indignat pe locuitorii singurei comune din România ce va avea metrou: "Fraților, totul trebuie să aibă o logică, traseul venea în linie dreaptă, pe Șoseaua Berceni, și era bun pentru toți locuitorii, dar așa, ca o arcadă?!"". 10 June 2023.

- ^ "Bucuresti metro expansion tendering". Railway Gazette. 22 February 2011. Archived from the original on 24 February 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ Olteanu, Anca (6 June 2019). "Planurile unui metrou pentru nepotii nepotilor: Magistrala M8 Crangasi – Dristor" [Plans for a subway for grandchildren's grandchildren: Line M8 Crangasi – Dristor]. wall-street.ro (in Romanian). InternetCorp SRL. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Ignat, Vlad. "Păianjenul Metrorex schimbă harta Capitalei. Bucureștenii se mută în subteran, din 2030" [Metrorex's Web Project changes the map of Bucharest. Bucharest moves underground by 2030]. Adevărul (in Romanian). Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ "În cele mai noi staţii de metrou vor circula cele mai vechi trenuri Metrorex". Economica.net. 31 December 2016.

- ^ "METRO BUCHAREST". CAF.

- ^ "Alstom to provide new Metropolis trains for Bucharest Metro Line 5". Alstom. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Bucharest metro Line 5 inaugurated by the Romanian President". Railway PRO. 15 September 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "Alstom to provide new Metropolis trains for Bucharest Metro Line 5". Alstom. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "Bucharest Metro Workers Continue Strike". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 9 April 2008.

- ^ "Grevă spontană la metrou. Nu se circulă pe nicio magistrală". 26 March 2021.

- ^ Fodor, Simona (24 May 2022). "More than 170 people evacuated after technical malfunction at Bucharest subway". Romania-Insider. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ "VIDEO Proiect pilot la Metrou : Metrorex montează porți de protecție ,,anti-suicid" pe peronul stației Berceni". 9 July 2022.

- ^ Andone, Anemona (3 May 2024). "Porți de protecție la metrou: Ce se mai întâmplă cu proiectul – pilot din stația Berceni". Economica.net (in Romanian).

- ^ "De ce nu vom avea vreodată sisteme de protecţie la metrou". May 2018.

- ^ "Metroul din București, singurul din lume care a funcționat cu călători în perioada de probe". Bucurestii Vechi si Noi (in Romanian). 24 November 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

External links

[edit]- Metrorex – official site Archived 30 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- 2015 Activity Report Archived 26 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Interactive subway map (in Romanian)

- Bucharest Metro Track Map (in Russian)

- Bucharest Metro Challenge

- Bucharest Subway info

- Bucharest Metro, practical map

- Map of future lines

- Bucharest Metro Map

Bucharest Metro

View on GrokipediaOverview

Network Characteristics

The Bucharest Metro network comprises five operational lines (M1 to M5), with a total route length of 78 km served by 64 stations as of October 2024.[9] These lines form a radial structure centered on central Bucharest, connecting residential districts, business areas, and transport hubs, though coverage remains limited in the city's northern and eastern peripheries compared to western sectors. The system handles peak-hour demands through frequent service intervals of 2-3 minutes on core segments, supporting modal integration with surface trams, buses, and regional rail at interchanges like Gara de Nord and Basarab.[10] Technical specifications include a standard track gauge of 1,435 mm and third-rail electrification at 750 V DC, enabling compatibility with conventional metro rolling stock.[1] Trains operate in formations of four to six cars, with models such as Bombardier Movia and CAF units providing capacities of up to 1,200 passengers per train; automation levels remain manual (GoA1) across the network, relying on driver-operated signaling.[10] Approximately 90% of the infrastructure is underground, utilizing cut-and-cover and tunnel boring methods, while surface and elevated sections on M1 and M3 account for the remainder, exposing the system to weather-related disruptions.[1]| Line | Length (km) | Stations | Key Route |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 28.2 | 22 | Pantelimon to Eroii Revoluției, with extensions to the airport planned. |

| M2 | 14.6 | 14 | Berceni to Pipera, serving northern suburbs.[10] |

| M3 | 7.5 | 7 | Preciziei to Anghel Saligny (partial, with extensions under construction).[10] |

| M4 | 7.8 | 8 | Gara de Nord to Străulești.[10] |

| M5 | 9.0 (phase 1) | 6 | Eroii 2 to Plaza România (operational since 2020, further phases pending).[10] |

Operator and Organizational Structure

The Bucharest Metro is operated by Metrorex S.A., a joint-stock company established to manage the subway system's daily operations, maintenance, and infrastructure development.[12] Metrorex handles passenger transportation, rolling stock management, and signaling systems across the network's approximately 70 kilometers of track and 45 stations as of recent reports.[13] As one of Bucharest's primary public transport entities, it integrates with surface systems but operates independently for underground services.[12] Metrorex is fully owned by the Romanian state through the Ministry of Transport, functioning as a state-owned enterprise (SOE) with activities classified under public and civil protection interests.[12][13] Governance aligns with Romania's SOE framework, which emphasizes corporate structures including a board of directors and executive management to oversee strategic decisions, financial performance, and compliance with national transport policies.[14] The company reports annually on operational metrics, such as ridership exceeding 142 million passengers in 2023, and pursues investments in line extensions and modernization under government directives.[12][9] Internally, Metrorex organizes into functional departments for operations, technical maintenance, commercial services, and project management, enabling coordinated execution of expansion projects like the ongoing Line M5 and M6 developments.[12] This structure supports its role in national urban mobility planning, where the central government retains oversight of metro operations distinct from municipal surface transport managed by entities like the Bucharest Transport Company (STB).[15] Financially, as a state entity, Metrorex relies on government funding for capital investments while generating revenue from fares, though it has faced operational losses typical of public utilities in Romania.[16]Historical Development

Pre-Construction Planning (1900s-1970s)

The first proposals for an underground railway system in Bucharest emerged in the early 1900s amid discussions on modernizing urban transport. In 1908, engineer Dimitrie Leonida addressed the concept in his bachelor's thesis, laying preliminary groundwork for subterranean lines.[17] By 1909–1910, during negotiations with the German firm Siemens & Halske for expanding tram infrastructure, engineers Dimitrie Leonida and Elie Radu, members of the Bucharest Technical Council, advocated redirecting allocated funds toward constructing a metro network instead of additional surface trams, citing the city's growing density as a rationale.[18][17] These early initiatives stalled due to high estimated costs and the perceived adequacy of existing surface options like trams and buses. In 1929–1930, a commission under architect Duiliu Marcu revisited the idea, evaluating potential routes but ultimately deeming surface transport more practical and economical for the era's traffic volumes.[17] Further proposals surfaced in the early 1940s, including alignments from the Hippodrome to Unirii Square, but World War II disrupted planning, diverting resources to wartime needs and halting urban infrastructure projects.[17] Postwar recovery under the communist regime initially prioritized industrialization and surface rail electrification over subways, with metro concepts remaining dormant amid restricted personal vehicle use and emphasis on trams.[19] By the early 1970s, escalating urban congestion from population growth—Bucharest's inhabitants exceeded 1.5 million—prompted renewed feasibility studies, drawing inspiration from established European systems.[19] On February 15, 1972, a specialized commission was formed to develop detailed plans, culminating in the establishment of the Bucharest Metro Company (Întreprinderea Metroul București) on February 1, 1975, to coordinate engineering and funding.[17][20] This phase focused on initial routes prioritizing north-south connectivity, setting the stage for groundbreaking on September 20, 1975.[17] Delays across decades stemmed primarily from fiscal constraints, geopolitical disruptions, and shifting priorities toward less capital-intensive transport modes.[17]Communist-Era Construction (1970s-1989)

Construction of the Bucharest Metro commenced on September 20, 1975, following approval by the communist government under Nicolae Ceaușescu, aimed at alleviating surface transport congestion amid rapid urbanization and industrial expansion in the capital.[21] The project prioritized connectivity between densely populated housing blocks and factories, reflecting socialist planning doctrines that emphasized collective mobility over private vehicle use, which was curtailed by fuel shortages and import restrictions. Initial tunneling employed cut-and-cover methods in softer soils and deeper bored tunnels elsewhere, with tracks standardized at 1,435 mm gauge and electrified at 750 V DC via third rail.[10] Domestic manufacturing of rolling stock by Astra Arad supplied the initial fleet of four-car trains, distinct from Soviet designs used in other Eastern Bloc metros.[17] Line M1, the inaugural route, partially opened on November 19, 1979, with an 8.63 km segment from Timpuri Noi to Semănătoarea (later renamed Petrache Poenaru), serving six stations including Grozăvești, Eroilor, and Izvor.[10] This east-west alignment facilitated worker commutes to industrial zones, carrying over 200,000 daily passengers within months despite incomplete electrification on some sections. Extensions accelerated in the early 1980s: on December 28, 1981, a 10.1 km eastern branch from Timpuri Noi to Republica added six stations; August 19, 1983, saw the opening of an 8.63 km western spur from Eroilor to Industriilor (now Preciziei) with four stations; December 22, 1984, extended Semănătoarea to Crângași by 0.97 km (one station); and December 24, 1987, connected Crângași to Gara de Nord via 2.83 km (one station), integrating key rail and bus interchanges.[10][1] Line M2, oriented north-south, broke ground amid the regime's 1980s austerity measures, which imposed rationing on food and energy to repay foreign debt, yet construction proceeded as a symbol of technological self-reliance. Its southern section from Piața Unirii 2 to Depoul IMGB (now Berceni) opened January 24, 1986, covering 9.96 km and six stations, while the northern extension to Pipera followed on October 24, 1987, adding 8.72 km and five stations, yielding a total line length of approximately 18.7 km.[1][10] Stations featured utilitarian concrete architecture with marble accents, prioritizing functionality over ornamentation, though some, like Piața Romană on M2, incorporated narrower platforms due to ad-hoc design changes ordered by regime officials to encourage pedestrian exercise.[3] Line M3's debut occurred shortly before the regime's collapse, with the 7.8 km Gara de Nord to Dristor segment opening August 17, 1989, adding six stations and linking central districts to eastern suburbs; this branch initially operated as part of M1 before designation as M3.[10] By late 1989, the network spanned roughly 40 km with over 30 stations operational, though extensive tunneling—totaling some 57 km of bored sections—outpaced full equipping due to material shortages and labor mobilization under centralized directives.[22] Engineering feats included navigating seismic risks and the Dâmbovița River, with safety protocols emphasizing overbuilt reinforcements despite economic constraints. The system's expansion, totaling 39 stations by August 1989, underscored the regime's commitment to infrastructural legacy, even as public hardships intensified.[22]Post-Revolution Expansions (1990s-2000s)

Following the Romanian Revolution of 1989, metro expansions proceeded at a markedly slower pace than during the communist era, constrained by severe economic contraction, hyperinflation exceeding 250% annually in the early 1990s, and the redirection of state resources toward macroeconomic stabilization rather than large-scale infrastructure.[23] Funding shortages and the collapse of centralized planning led to prolonged delays in ongoing projects, with only minimal extensions completed in the 1990s.[1] The sole significant extension in the early post-revolution years occurred on Line M1, with a 1.4 km segment from Republica to Pantelimon entering service on July 7, 1991, adding one station to serve northeastern suburbs.[24] This short branch addressed immediate local demand but reflected the era's fiscal limitations, as broader plans for ring lines and radial expansions stalled amid privatization efforts and industrial decline.[25] Activity resumed modestly in the 2000s as Romania pursued EU accession and accessed foreign loans for transport upgrades. Line M4, the first new route initiated post-1989, opened its initial 3.7 km section on March 1, 2000, linking Gara de Nord to 1 Mai via four stations (Gara de Nord 2, Basarab 2, Grivița, and 1 Mai), facilitating northwestward connectivity and interchanges with Line M1.[20] Further progress on M4 was incremental, with planning for extensions beyond 1 Mai but no major additions until later phases.[10] Line M3 saw its last pre-contemporary extension on November 20, 2008, with a 2.4 km branch from Nicolae Grigorescu to Anghel Saligny (formerly Linia de Centura), incorporating two new stations (1 Decembrie 1918 and Anghel Saligny) to enhance eastern peripheral access near the ring road.[26] This project, delayed by funding issues, improved links to industrial zones but highlighted persistent underinvestment, as the metro's total length grew by less than 10 km over the decade despite rising urban pressures.[20] Overall, these developments prioritized targeted relief over ambitious growth, with Metrorex focusing on maintenance amid budgetary constraints.[24]Contemporary Developments (2010s-2025)

Construction on Bucharest Metro Line M5 advanced through the 2010s, with Metrorex announcing tenders in February 2011 for the initial 2.6 km section from Eroilor to Incubatorul de Afaceri, valued at 2.26 billion lei.[27] The line's first operational phase, extending 6.87 km from Eroilor to Râul Doamnei and serving ten stations, commenced service on September 15, 2020, after delays attributed to funding and technical challenges.[28] [29] This EU-co-financed project enhanced connectivity to western Bucharest districts, incorporating modern signaling systems supplied by Alstom.[28] Line M6 development progressed in the 2020s, focusing on a 5.1 km airport link from 1 Mai to Henri Coandă International Airport in Otopeni. A financing agreement secured European funds in November 2020, targeting completion by November 2026, though timelines shifted to 2028 amid construction complexities.[30] [31] Key contracts included a March 2022 award to a Turkish consortium for tunneling and stations, valued at 1.2 billion lei, followed by additional packages signed in March 2025.[32] [33] Tunnel boring machine excavation launched on April 9, 2025, between 1 Mai and Tokyo stations, with the Romanian government approving purchase of 12 new electric trains in April 2025 at a cost of 1 billion lei to equip the line.[34] [35] Extensions to existing lines gained momentum by mid-decade. For Line M4, financing contracts signed in June 2024 supported an 11.9 km extension with 14 new stations from Gara de Nord southward, with tenders launched in April 2024 and consortia awarded contracts in September 2025 totaling over 17 billion lei for 60-month execution.[36] [11] Metrorex's 2021-2030 investment framework outlined 94 km of new lines and 90 stations, alongside fleet upgrades including a $230 million rolling stock replacement for M4 announced in April 2025 and Alstom's delivery of a CBTC-compatible driving simulator for M5 in October 2024 to support higher-frequency operations.[9] [7] [37] These initiatives reflect sustained efforts to modernize amid Romania's infrastructure constraints, though historical delays underscore execution risks.Infrastructure

Lines and Stations

The Bucharest Metro network consists of five operational lines—M1, M2, M3, M4, and M5—serving 64 stations over approximately 78 km of track. These lines form a core rapid transit system primarily underground, with interchanges at major hubs facilitating transfers across the network. Line M1 and M3 share a 8.67 km segment and seven stations in the eastern section, reflecting historical construction overlaps.[9][38] Line M1 operates as a semi-circular route from Pantelimon in the eastern suburbs to Dristor 2, encompassing 22 stations and primarily serving industrial and residential areas in the east. Key stations include Republica, Titan, and Obor, with interchanges to M3 at Dristor, Mihai Bravu, and Nicolae Grigorescu. The line's configuration supports high connectivity in densely populated zones.[39][40] Line M2 functions as the primary north-south axis, extending 20.28 km from Pipera in the northern business district to Berceni (via Tudor Arghezi) in the south, with around 15 stations. It passes through central landmarks such as Piața Victoriei, Universitate, and Piața Unirii, where it interchanges with M3, making it one of the busiest corridors for commuters. Stations like Aurel Vlaicu and Apărătorii Patriei connect residential and commercial hubs.[41][42] Line M3 spans 22.2 km eastward from Preciziei in the west to Anghel Saligny, featuring 15 stations and sharing trackage with M1 between Dristor and Nicolae Grigorescu. Western stations include Păcii, Gorjului, and Politehnica, while central interchanges occur at Eroilor (with M5), Izvor, and Piața Unirii (with M2). The line supports cross-city travel, linking western suburbs to eastern districts.[43][38] Line M4, a shorter northwest route of 7.44 km, connects Gara de Nord (Bucharest North Railway Station) to Străulești with 8 stations, including Basarab, Grivița, 1 Mai, and Jiului. It provides essential links to rail services and northern residential areas, with potential for future extensions.[44][45] Line M5, the newest addition opened in phases starting September 15, 2020, operates a 6.87 km Y-shaped branch from Eroilor to Râul Doamnei and Valea Ialomiței, serving 10 stations in the Drumul Taberei area. Stations include Parc Drumul Taberei, Romancierilor, and Tudor Vladimirescu, focusing on underserved southwestern suburbs with modern infrastructure. It interchanges with M3 at Eroilor.[46][47]Technical Systems and Engineering

The Bucharest Metro employs a track gauge of 1,432 mm, slightly narrower than the standard 1,435 mm used in the Romanian national rail network, facilitating compatibility with mainline loading gauges while optimizing for urban constraints.[48] Electrification is provided via a 750 V DC third rail system across the operational network, with overhead catenary lines (OHLE) utilized exclusively in depots for maintenance flexibility.[48] [1] The power supply infrastructure supports traction for trains and auxiliary needs across 63 stations and six depots, drawing from dedicated electro-energetic installations to ensure reliability amid high demand.[18] Signaling follows Romanian mainline railway conventions, incorporating three-aspect color-light signals where yellow indicates a subsequent red signal, enabling automatic train operation on select segments.[1] Line 5 represents a modernization milestone as Romania's first implementation of Communications-Based Train Control (CBTC), commissioned in phases starting September 2020, which supports headways as low as 90 seconds through continuous train-to-infrastructure telecommunications for precise traffic management and automatic train protection.[49] [50] Tunnel construction varies by era and geology, with early lines (1970s–1980s) predominantly using cut-and-cover methods for shallow sections and open-face shield tunneling for deeper alignments, as seen in rehabilitations from 1989 onward.[51] Recent expansions, such as Line 5, employ Earth Pressure Balance (EPB) tunnel boring machines (TBMs) with 6.6 m excavation diameters for twin tunnels, enabling efficient boring through urban alluvial soils while minimizing surface disruption; for instance, sections like Eroilor 2 station involved TBM passage beneath operating infrastructure with real-time monitoring.[29] [52] Ventilation systems feature reversible axial fans at stations and intermediate ventilation shafts, capable of 400,000 m³/h (111 m³/s) extraction to generate 2 m/s longitudinal airflow in tunnels, countering smoke backlayering during incidents.[53] Safety engineering emphasizes self-rescue protocols, with fire strategies classifying risks (e.g., tolerable for derailments, undesirable for large tunnel fires affecting up to 1,000 passengers) and evacuation modeling yielding 3–6 minute times for platforms and stations; enhancements include platform screen doors (PSDs) and smoke curtains on newer lines to compartmentalize hazards.[53]Architectural and Design Features

The Bucharest Metro's stations, largely developed during Romania's communist era from the 1970s to 1980s, adopt a utilitarian architectural style aligned with socialist principles, prioritizing functional efficiency and minimal ornamentation over aesthetic extravagance.[19] Initial designs emphasized spacious underground interiors to accommodate high passenger volumes, with concrete vaults and simple pillar arrangements supporting wide platforms designed for six-car trains measuring 129 meters in length.[1] Flooring often incorporates durable local materials such as marble or limestone, reflecting resource constraints and state-directed construction practices of the period.[54] A distinctive example is Politehnica station, opened in 1983, where the platform floor features polished limestone slabs quarried from Romania's Apuseni Mountains, embedding visible marine fossils dating back approximately 80 million years to the Cretaceous period, serving as an unintended geological exhibit within the transit infrastructure.[54] [55] Many stations employ broad arched ceilings without intermediate supports to maximize open space, though this approach has occasionally strained structural integrity in areas with unstable subsurface conditions.[56] Lighting remains subdued, evoking the era's austerity, with exposed utilities and minimal decorative elements underscoring the system's engineering focus amid economic limitations.[57] Post-1989 expansions and renovations introduce varied modern influences, incorporating sleek metallic screens and modular elements for improved aesthetics and user experience, as seen in upgrades utilizing systems like Luxalon V100 panels.[58] Recent projects, such as the Line 5 extension, integrate station-specific designs drawing from Bucharest's historical context, employing differentiated arch forms and proportional motifs to foster visual cohesion while enhancing connectivity between heritage districts and contemporary urban zones.[59] These evolutions balance legacy functionalism with adaptive enhancements, maintaining the metro's role as a pragmatic underground network amid ongoing infrastructural demands.[59]Operations

Service Schedules and Capacity

The Bucharest Metro operates daily from 5:00 a.m. to 11:00 p.m., with the last trains departing from terminal stations at 11:00 p.m.[60][61] This schedule applies uniformly across all lines without extensions for weekends or holidays, though minor adjustments may occur for maintenance or special events as announced by Metrorex.[60] Train frequencies vary by line and time of day, with headways of 3 to 5 minutes during morning and evening rush hours (typically 6:00–9:00 a.m. and 4:00–7:00 p.m.) on high-demand lines such as M1 and M2, extending to 6 to 12 minutes during off-peak hours.[62][63] Less utilized segments, including parts of M3 and M5, may see intervals up to 10 minutes even in peak periods due to lower ridership and operational constraints.[64] These intervals are managed via fixed timetables, with real-time adjustments limited by signaling systems and fleet availability.[12] Most trains in service are six-car sets, offering a nominal capacity of 1,200 passengers per train at standard loading densities of 4 passengers per square meter, including standing room beyond fixed seating for 200–220 passengers.[65][66] CAF-supplied units on lines M2 and M5, introduced from 2015, achieve this via 114-meter lengths with open-gangway designs for improved flow, while Alstom Metropolis trains on M5, delivered starting 2024, incorporate similar specifications with 216 seats and advanced crowd management features.[67][68] Older Adtranz and Astra IVA rolling stock on M1 and M3 provides comparable capacities but with dated interiors limiting effective use during peaks.[69] System-wide capacity is constrained by infrastructure, with peak-hour throughput reaching design limits on core segments, where trains operate at full load and platforms experience overcrowding; daily operations support an average of around 500,000 passengers, though surges to over 600,000 occur during high-demand periods.[12][70] Metrorex reports indicate that signaling upgrades and fleet modernization have incrementally raised effective capacity, but bottlenecks at interchanges like Piața Unirii persist due to station geometries and evacuation times.[12]Fare Systems and Revenue

The Bucharest Metro employs a fare structure managed by Metrorex, featuring single-use magnetic tickets, multi-trip cards, and subscription passes, with options for integration with surface transport via the STB network since the unified ticketing system's implementation in 2021. Single-trip tickets, valid for one metro journey without time restrictions, cost 5 RON as of September 2025, reflecting a hike from 3 RON effective January 1, 2025, to mitigate operational shortfalls.[63] [71] Multi-trip variants include 2-trip cards at 10 RON and 10-trip cards at 40 RON, purchasable via station vending machines accepting cash or cards.[72] Integrated metropolitan passes extend validity to 120 minutes across metro and select STB lines (buses, trams, trolleybuses), priced at 5 RON for basic access, promoting seamless transfers but limited to non-express surface routes.[73] Subscription options, such as monthly nominal passes on rechargeable contactless cards, cost 140 RON for combined metropolitan and metro use with 15-minute peak access timing to manage capacity; shorter-term passes include daily options at around 8 RON and weekly at 15 RON, though unlimited monthly variants remain closer to 100 RON post-2025 adjustments.[74] [71] Discounts apply for students and specific groups upon ID verification, but fares exclude airport express lines following the discontinuation of certain bundled passes in February 2025.[75] Metrorex generates revenue mainly from ticket sales, augmented by minor sources like advertising, yet fares cover only a fraction of costs due to subsidized pricing aimed at accessibility. With 142.8 million passengers in 2023, fare income supports basic operations but yields persistent deficits, as evidenced by projected 2025 losses of 181.83 million RON despite post-hike revenue gains from passenger transport. [76] The operator depends on Ministry of Transport subsidies—historically comprising half or more of budget needs—to fund maintenance, expansions, and wages, with total operating revenue declining 13.39% in recent audited periods amid rising expenditures.[13] [77] This model reflects broader public transport economics in Romania, where low fares prioritize ridership over self-sufficiency, necessitating annual state bailouts exceeding 300 million EUR in some years for infrastructure alone.[77]Ridership and Performance Metrics

The Bucharest Metro handles an average of approximately 500,000 passengers per day under normal conditions, corresponding to over 15 million passengers per month. In 2023, annual ridership exceeded 140 million passengers, reflecting partial recovery from pandemic-era declines. Ridership surged 53% in the first quarter of 2022 compared to the prior year, driven by eased restrictions and office returns. The system serves roughly 20% of Bucharest's public transport passengers despite covering only 4% of the network length. Peak-hour operations push trains to full capacity, with frequencies of 3 to 5 minutes during rush periods (7:00-9:00 and 17:00-19:00). Modern six-car trains offer 216 seated places and a total capacity of 1,968 passengers at maximum density (8 per square meter), though older rolling stock varies in configuration. Metrorex has increased train deployments during peaks to accommodate demand, but the network's 80 km length and aging infrastructure limit overall throughput to moderate levels relative to European peers. Performance metrics indicate reliable baseline service, with the network demonstrating moderate robustness against disruptions, sustaining operations up to 45% node failures in simulations before systemic collapse. Specific on-time data remains limited in public reports, though anecdotal evidence and operational adjustments suggest frequent minor delays from signaling and maintenance issues. Fare revenue, tied to ridership, contributed to Metrorex's 2023 operating budget, though subsidies cover most costs amid recovering volumes.Future Developments

Ongoing Construction Projects

The primary ongoing construction project for the Bucharest Metro is Line M6, a 14.2-kilometer automated line connecting 1 Mai station to Henri Coandă International Airport (Otopeni), featuring 12 stations including Pajura, Expoziției, Piața Montreal, Gara Băneasa, Băneasa Airport, Tokyo, Washington, Paris, and the airport terminal.[78][33] Tunneling commenced in April 2025 with the launch of tunnel boring machines (TBMs), including the "Sfânta Maria" TBM, which completed excavation of the first tunnel segment between Tokyo and Băneasa Airport stations by August 19, 2025, covering approximately 900 meters.[79][78][80] Contracts for key packages have advanced the project, with Package 2 signed on March 26, 2025, encompassing design and construction elements, while building permits for Lot 1.1 (1 Mai to Tokyo) and Lot 1.2 (Tokyo to Otopeni Airport) were issued in December 2023 and August 2024, respectively.[33][81] As of October 2025, the second tunnel segment in the south section has been completed, and excavation continues with TBMs advancing toward additional stations, supported by ongoing surface works such as traffic restrictions in Otopeni starting September 9, 2025.[80][82][83] The line is designed for driverless operation with a capacity of up to 50,000 passengers per hour per direction upon completion, projected around 2028, though delays in prior phases have extended timelines.[84] Other extensions, such as the M4 line from Gara de Nord to Gara Progresul (approximately 12 kilometers with 14 stations), have seen tenders awarded in September 2025 for contracts valued at over 17 billion lei, but substantive construction has not yet commenced, with a 60-month execution period anticipated to begin shortly thereafter.[11] Metrorex's broader 2021–2030 investment program envisions 94 kilometers of new lines and 90 stations overall, but active tunneling and major earthworks remain concentrated on M6 as of late 2025.[9]Approved Expansion Plans

The Bucharest Metro's approved expansion plans, as outlined in Metrorex's 2021–2030 investment programme, encompass the construction of approximately 94 kilometers of new lines and 90 stations to address growing urban demand and integrate underserved areas.[9] This programme, endorsed by the operator, prioritizes five new lines totaling 76.5 kilometers alongside extensions to four existing lines exceeding 17 kilometers, funded through national budgets, European Union grants, and public-private partnerships.[85] Implementation timelines target completion by 2030, contingent on securing tenders and regulatory approvals, with an emphasis on enhancing connectivity to peripheral districts and reducing surface traffic congestion.[9] A key component is Metro Line M7, approved via a partnership agreement by the Bucharest General Council on June 25, 2025, spanning 13 kilometers with 15 stations to link southwestern suburbs like Bragadiru through central areas such as Piața Unirii to northeastern locales including Voluntari.[86] [87] This east-west corridor, formalized through an inter-institutional protocol signed on September 3, 2025, by the Ministry of Transport and local authorities, aims to serve high-density residential and industrial zones previously reliant on bus and tram services.[88] The project, estimated at significant capital outlay, incorporates feasibility studies confirming viability for automated operations and integration with existing lines at interchanges like Piața Unirii.[86] Additional approved extensions include a 1.6-kilometer addition to Line M2 eastward along Dimitrie Pompeiu Boulevard and Petricani Street toward Pipera Boulevard, incorporating two new stations to bolster northern business district access.[89] These plans, while advancing procurement phases, face execution risks from historical delays in Romanian infrastructure projects, though recent tender awards for related segments signal momentum.[11] Overall, approvals reflect strategic alignment with urban growth patterns, prioritizing empirical ridership projections over speculative extensions.[9]Proposed Initiatives and Feasibility Studies

In September 2025, an inter-institutional cooperation protocol was signed to advance Metro Line M7, a proposed 26-kilometer double-track route connecting Bragadiru in the southwest to Voluntari in the northeast, featuring 27 stations and two depots.[90] This initiative aims to alleviate surface traffic congestion by providing radial connectivity across densely populated suburbs, with an estimated cost of EUR 2.47 billion excluding VAT, though a feasibility study is underway to refine the final figure, technical specifications, and funding requirements.[90] The project aligns with the Bucharest-Ilfov regional development strategy and Romania's 2021–2030 investment program, potentially drawing EU funds from the 2021–2027 Transport Program upon study completion.[90] A feasibility study for extending Metro Line M4 from Gara Progresu to Lac Străulești, incorporating a segment to Gara de Nord, was contracted in September 2017 with Swiss-Romanian Cooperation Program funding.[91] Valued at RON 19.71 million excluding VAT, the study—supported by CHF 8.5 million in non-reimbursable Swiss aid out of a total CHF 11.9 million budget—encompasses design and consultancy for key stations including Gara de Nord, Palatul Parlamentului, Piața Regina Maria, Viilor, and Gara Progresu.[91] Intended to enhance east-west connectivity and reduce regional disparities, the study's outcomes remain pivotal for potential approval, though progress has been slowed by funding dependencies and integration challenges with existing infrastructure.[91]Rolling Stock

Fleet Composition and Specifications

The Bucharest Metro fleet consists primarily of six-car articulated trainsets designed for rapid transit operations on its four operational lines. As of 2024, the system operates approximately 82 to 83 trainsets, comprising older domestically produced units alongside more recent imports from international manufacturers, with ongoing integration of new Alstom trains for Line M5.[9][49] These trains run on a 750 V DC third-rail electrification system and feature automatic train operation capabilities on select lines, though manual intervention remains common due to infrastructure limitations. Key fleet types include:| Type | Manufacturer | Number of Trainsets | Build Years | Primary Lines | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVA (Astra) | Astra Vagoane Arad | 15 | 1976–1992 | M4 | Older generation; some units modernized for continued service; being phased out with newer procurements.[9] |

| BM2/BM21 (Movia 346) | Adtranz/Bombardier (now Alstom) | 44 | 2002–2008 | M1, M2, M3 | Intermediate generation; stainless steel bodies; equipped with regenerative braking; maintained by Alstom since 2004.[9][92] |

| BM3 | CAF | 24 | 2013–2016 | M2 | Newer series; includes two batches (16 initial + 8 additional); improved energy efficiency and passenger information systems.[9][18] |

| BM4 (Metropolis) | Alstom | 13 (initial delivery) | 2020–2024 | M5 | Latest addition; six-car sets with 114 m length, four double doors per side, LED lighting, and CBTC signaling for reduced headways; capacity up to 1,200 passengers at 4 per m²; first unit arrived in 2024.[92][93][7] |

Procurement, Maintenance, and Modernization

The rolling stock for the Bucharest Metro has primarily consisted of locally produced trains from Astra Vagoane Călători, with types such as IVA (also designated BM1) forming the backbone of the fleet since the system's inception in the 1970s and 1980s, totaling hundreds of cars initially assembled in Romania.[1] Procurement shifted toward international suppliers in the 2010s to address aging infrastructure, with Metrorex awarding a contract for 16 BM3 trains from Construcciones y Auxiliar de Ferrocarriles (CAF) in two lots, the second commissioned in 2016 to enhance capacity on existing lines.[18] In 2020, Alstom secured a deal for up to 30 Metropolis trains tailored for Line M5, featuring stainless steel bodies, 114-meter lengths, and 3-meter widths to accommodate higher ridership, with deliveries supporting network expansion.[66] A 2019 tender attracted bids from Alstom, CAF, CRRC-Qingdao/Astra consortium, and Hyundai Rotem, though technical evaluations favored established European suppliers amid concerns over compatibility and reliability.[94] Maintenance operations are outsourced to Alstom under a comprehensive contract signed in late 2021, valued at approximately €500 million and extending until 2036, encompassing preventive, corrective, and overhaul services for the entire active fleet of 82 trains as of contract inception.[92] This arrangement builds on Alstom's prior involvement since 2004, focusing on both legacy Astra-built units and newer imports to minimize downtime, with activities conducted at dedicated depots like Ciurel, where constructive assessments ensure compliance with operational standards.[95] Metrorex reports emphasize mileage tracking and fleet availability metrics, though challenges persist with older series requiring frequent interventions to sustain service intervals.[18] Modernization efforts integrate overhauls within the Alstom maintenance framework alongside targeted procurements to phase out obsolete models, including a 2025 initiative estimated at 1 billion RON (about €201 million including VAT) for new trains to replace IVA units on Line M4, aiming to improve energy efficiency and passenger comfort.[96] A broader $230 million investment announced in 2025 targets fleet upgrades across lines, prioritizing replacement of high-maintenance legacy stock to boost reliability and reduce operational costs, with Alstom's Metropolis series incorporating advanced signaling for future automation compatibility.[7] These upgrades address empirical gaps in fleet performance, such as elevated failure rates in pre-1990s trains, without relying on unverified political narratives around supplier selection.[49]Safety and Incidents

Technical Failures and Accidents

The Bucharest Metro has encountered numerous technical disruptions, primarily stemming from equipment malfunctions and infrastructure wear, contributing to service delays and safety concerns. Between January 2019 and December 2022, the system recorded 352 disruption events, with technical failures comprising 17.5% (61 incidents) and train-specific failures accounting for 16.95% (59 incidents).[97] Line M2 experienced the highest share at 27.6% of disruptions, followed by M1 at 16.9%, while Gara de Nord station was the most affected site with 11.21% of events.[97] The average recovery time for these incidents was 21 minutes, with 79.31% resolved within one hour, though passenger emergencies (14.65% of cases) often compounded delays.[97] Notable technical failures include a June 16, 2016, incident where a moving train caught fire near Timpuri Noi station, occurring just days after another major disruption and highlighting recurring electrical and mechanical vulnerabilities.[98] On May 24, 2022, a train departing Piața Romană toward Berceni experienced a breakdown with smoke emission at approximately 8:42 a.m., necessitating the evacuation of 172 passengers through the tunnel and temporary suspension of services on the affected line.[99] [100] In April 2024, a train leaving Basarab station operated with its doors open, creating a direct hazard for passengers and underscoring lapses in door interlocking systems.[101] These events reflect broader challenges with the metro's Soviet-era infrastructure and fleet, where signal, power, and rolling stock issues predominate, though no large-scale derailments or fatalities directly attributable to technical causes have been widely documented in recent years.[97] Metrorex, the operating authority, has faced scrutiny for maintenance shortcomings exacerbating such failures, with disruptions peaking at 105 in 2021 amid increased ridership post-pandemic restrictions.[97]Crime, Suicides, and Passenger Risks

The Bucharest Metro reports low incidences of violent crime, with assaults and robberies rare compared to petty thefts such as pickpocketing, which occur primarily in overcrowded trains during peak hours.[102] [63] General crime perceptions in Bucharest, including public transport, align with a low overall index, though tourists and locals are advised to remain vigilant against opportunistic theft in high-traffic stations.[103] Suicide attempts involving jumps onto tracks represent a persistent safety challenge, with Metrorex withholding comprehensive public statistics on occurrences or survival rates.[104] Available data indicate 23 such incidents between approximately 2010 and 2017, including 9 fatalities.[105] Notable recent cases encompass a fatal jump at Constantin Brâncoveanu station on March 24, 2022, and a non-fatal attempt at Eroii Revoluției station in 2025, frequently halting services for investigations and cleanup.[106] In response, Metrorex launched a prevention awareness campaign in October 2021 and committed to installing platform-edge barriers on the expanding M4 line by 2025.[107] Broader passenger risks arise from infrastructural vulnerabilities, including the lack of platform screen doors across most of the aging network, which facilitates both intentional acts and accidental falls—exacerbated by gaps between platforms and tracks.[108] Metrorex's 2023 annual report highlights ongoing investments in safety enhancements, such as optimized operations and user protections, yet older stations remain prone to these hazards without full retrofitting.[12] Overall, the system maintains a reputation for routine safety, with air quality and overcrowding posing secondary concerns rather than acute threats.[109]Labor Actions and Disruptions