Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

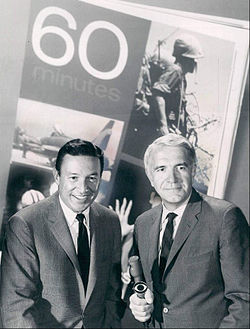

Mike Wallace

View on WikipediaMyron Leon Wallace (May 9, 1918 – April 7, 2012) was an American broadcast journalist, and television personality. Known for his investigative journalism,[1] he interviewed a wide range of prominent newsmakers during his seven-decade career. He was one of the original correspondents featured on CBS news program 60 Minutes, which debuted in 1968. Wallace retired as a regular full-time correspondent in 2006, but still appeared occasionally on the series until 2008. He is the father of Chris Wallace.

Key Information

Wallace interviewed many politicians, celebrities, and academics throughout his life.[2][3][4]

Early life

[edit]Wallace, whose family's surname was originally Wallik, was born on May 9, 1918, in Brookline, Massachusetts, to Russian Jewish immigrant parents.[5][6] He identified as Jewish and claimed it was his ethnicity (instead of religion) throughout his life. His father was a grocer and insurance broker.[7] Wallace attended Brookline High School, graduating in 1935.[8] He graduated from the University of Michigan four years later with a Bachelor of Arts degree. While a college student, he was a reporter for the Michigan Daily and belonged to the Alpha Gamma chapter of the Zeta Beta Tau fraternity.[9]

Career

[edit]1930s–1940s: Radio

[edit]Wallace appeared as a guest on the popular radio quiz show Information Please on February 7, 1939, when he was in his last year at the University of Michigan. He spent his first summer after graduation working on-air at Interlochen Center for the Arts.[10] His first radio job was as a newscaster and continuity writer for WOOD radio in Grand Rapids, Michigan. This lasted until 1940, when he moved to WXYZ radio in Detroit, Michigan, as an announcer. He then became a freelance radio worker in Chicago.

Wallace enlisted in the United States Navy in 1943 and during World War II served as a communications officer on the USS Anthedon, a submarine tender. He saw no combat but traveled to Hawaii, Australia, and Subic Bay in the Philippines, then patrolling the South China Sea, the Philippine Sea and south of Japan. After being discharged in 1946, Wallace returned to Chicago.

Wallace announced for the radio shows Curtain Time,[11] Ned Jordan: Secret Agent, Sky King, The Green Hornet,[12] and The Spike Jones Show.[13] It is sometimes reported Wallace announced for The Lone Ranger,[14] but Wallace said that he never had done so.[15] From 1946 through 1948, he portrayed the title character on The Crime Files of Flamond on WGN and in syndication.

Wallace announced wrestling in Chicago in the late 1940s and early 1950s, sponsored by Tavern Pale beer.

In the late 1940s, Wallace was a staff announcer for the CBS radio network. He had displayed his comic skills when he appeared opposite Spike Jones in dialogue routines. He was also the voice of Elgin-American in the company's commercials on Groucho Marx's You Bet Your Life. As Myron Wallace, he portrayed New York City detective Lou Kagel on the short-lived radio drama series Crime on the Waterfront.

1940s–1960s: Television

[edit]In 1949, Wallace began to move to the new medium of television. In that year, he starred under the name Myron Wallace in a short-lived police drama, Stand By for Crime.[16]

Wallace hosted a number of game shows in the 1950s, including The Big Surprise, Who's the Boss? and Who Pays?. Early in his career, Wallace was not known primarily as a news broadcaster. It was not uncommon during that period for newscasters to announce, to deliver commercials and to host game shows; Douglas Edwards, John Daly, John Cameron Swayze and Walter Cronkite hosted game shows as well. Wallace also hosted the pilot episode of Nothing but the Truth, which was helmed by Bud Collyer when it aired under the title To Tell the Truth. Wallace occasionally served as a panelist on To Tell the Truth in the 1950s. He also made commercials for a variety of products, including Procter & Gamble's Fluffo brand shortening.[citation needed] In the summer of 1959, he was the host on the NBC game show Who Pays?.[17]

Wallace also hosted two late-night interview programs, Night Beat (broadcast in New York City during 1955–1957, only on DuMont's WABD)[18] and The Mike Wallace Interview on ABC in 1957–1958. See also Profiles in Courage, section: Authorship controversy.

In 1959, Louis Lomax told Wallace about the Nation of Islam. Lomax and Wallace produced a five-part documentary about the organization, The Hate That Hate Produced, which aired during the week of July 13, 1959. The program marked the first time that most white people heard about the Nation, its leader, Elijah Muhammad, and its charismatic spokesman, Malcolm X.[19]

By the early 1960s, Wallace's primary income came from commercials for Parliament cigarettes, touting their "man's mildness" (he had a contract with Philip Morris to pitch their cigarettes as a result of the company's original sponsorship of The Mike Wallace Interview).

Between June 1961 and June 1962, Wallace and Joyce Davidson hosted a New York-based nightly interview program for Westinghouse Broadcasting[20] called PM East for one hour; it was paired with the half-hour PM West, which was hosted by San Francisco Chronicle television critic Terrence O'Flaherty. Westinghouse syndicated the series to television stations that it owned and to a few other cities. WFAA channel 8 in Dallas, Texas carried it, but viewers in other southwestern states, in the Deep South and in the metropolitan areas of Chicago and Philadelphia were unable to watch it.

A frequent guest on the PM East segment was Barbra Streisand, though only the audio of some of her conversations with Wallace survives,[20] as Westinghouse wiped the videotapes and kinescopes were never made or were thrown away.

Also in the early 1960s, Wallace was the host of the David Wolper–produced Biography series.

After his elder son's death in 1962, Wallace decided to get back into news and hosted an early version of CBS Morning News from 1963 through 1966. In 1964 he interviewed Malcolm X, who, half-jokingly, commented "I probably am a dead man already."[21] The black leader was assassinated a few months later in February 1965.

1960s–2000s: 60 Minutes

[edit]

Wallace's career as the lead reporter on 60 Minutes led to some run-ins with the people interviewed and claims of misconduct by female colleagues. Wallace was critical of feminism. In the 1950s, Wallace was quoted as saying, "It helps if a wife walks one step behind her husband. European women have that by-your-leave-my-lord attitude that you just don’t find in American women. They’re infinitely more self-absorbed. European women let the men run things and quite right they are too!" When questioned in a 1977 interview with Good Housekeeping, Wallace claimed to "stand by every word" of what he had said, but by 1979, he had softened that view somewhat. He also claimed feminism made women more unattractive, saying, "So many feminists in our business lose that soft, round, appealing quality—I don’t know how else to define it."[22]

While interviewing Louis Farrakhan, Wallace alleged that Nigeria was the most corrupt country in the world. Farrakhan immediately shot back that Americans were in no moral position to judge, declaring "Has Nigeria dropped an atomic bomb that killed people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Have they killed off millions of Native Americans?" "Can you think of a more corrupt country?" asked Wallace. "I'm living in one," said Farrakhan.[23]

Wallace interviewed General William Westmoreland for the CBS special The Uncounted Enemy: A Vietnam Deception that aired on January 23, 1982.[24] Westmoreland then sued Wallace and CBS for libel. The trial ended in February 1985 when the case was settled out of court just before it would have gone to the jury. Each side agreed to pay its own costs and attorney fees, and CBS issued a clarification of its intent with respect to the original story.

In 1981, Wallace was forced to apologize for a racial slur he had made about Blacks and Hispanics. During a break while preparing a 60 Minutes report on a bank that had been accused of duping low-income Californians, Wallace was caught on tape joking that "You bet your ass [the contracts are] hard to read if you're reading them over the watermelon or the tacos!"[25][26][27][28]

Attention was again drawn to that incident several years later when protests were raised after Wallace was selected to deliver a university commencement address during a ceremony within which Nelson Mandela was awarded an honorary doctorate in absentia for his fight against racism. Wallace initially called the protesters' complaint "absolute foolishness".[29] However, he subsequently apologized for his earlier remark and added that when he had been a student decades earlier on the same university campus, "though it had never really caused me any serious difficulty here ... I was keenly aware of being Jewish, and quick to detect slights, real or imagined.... We Jews felt a kind of kinship [with blacks]", but "Lord knows, we weren't riding the same slave ship."[30]

Wallace's reputation has been retrospectively affected by his admission that he had harassed female colleagues at 60 Minutes over many years. In the 1970s and 1980s, he was known for putting his hand on the backs of his female CBS News co-workers and unsnapping the clasps on their bras, as well as inquiring about their sex lives. Wallace admitted this in Rolling Stone magazine in 1991: 'It wasn't a secret. I have done that'.[31] In 2018, claims of sexual misconduct at 60 Minutes led to the resignation of executive producer Jeff Fager, who had assumed the role of Executive Producer following the retirement of the show's creator, Don Hewitt. He resigned several months after a July 27 story by Ronan Farrow in The New Yorker.[32] Not only did Farrow's story accuse Fager of ignoring and enabling misconduct by several high-ranking male producers at 60 Minutes, but Farrow also cited former employees who accused Fager himself of misconduct.[33]

Former 60 Minutes producer Ira Rosen wrote that, in addition to the aforementioned sexual harassment, Wallace would also verbally abuse his colleagues. Rosen painted the 60 Minutes working environment during his tenure as a toxic workplace with frequent incidents of sexual and verbal harassment.[34]

On March 14, 2006, Wallace announced his retirement from 60 Minutes after 37 years with the program. He continued working for CBS News as a "Correspondent Emeritus", albeit at a reduced pace.[35] In August 2006, Wallace interviewed Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.[36] Wallace's last CBS interview was with retired baseball star Roger Clemens in January 2008 on 60 Minutes.[37] Wallace's previously vigorous health (Morley Safer described him in 2006 as "having the energy of a man half his age") began to fail, and in June 2008 his son Chris said that his father would not be returning to television.[38]

Wallace expressed regret for not having secured an interview with First Lady Pat Nixon.[39]

Personal life

[edit]

Wallace had two children with his first wife, Norma Kaphan.[40] Their younger son, Chris, is also a journalist. Their elder son, Peter, died at age 19 in a mountain-climbing accident in Greece in 1962.[41]

From 1949 to 1954, Wallace was married to his second wife, Patrizia "Buff" Cobb, an actress and stepdaughter of Gladys Swarthout. The couple hosted the Mike and Buff Show on CBS television in the early 1950s. They also hosted All Around Town in 1951 and 1952.[42] She died in 2010.[5]

He was married to his third wife, Lorraine Perigord, from 1955 until their divorce in 1986.[5]

The same year as his divorce from his third wife (1986), he married his fourth and final wife, Mary Yates, the widow of one of his best friends and television producer, Ted Yates, who died in 1967 while on assignment for NBC News during the Six-Day War.[5]

In addition to his two sons, Wallace had a stepdaughter, Pauline Dora, and two stepsons, Eames and Angus Yates.[5]

For many years, Wallace unknowingly suffered from depression. In an article that he wrote for Guideposts, Wallace related, "I'd had days when I felt blue and it took more of an effort than usual to get through the things I had to do."[43] His condition worsened in 1984 after General William Westmoreland filed a $120 million libel lawsuit against Wallace and CBS over statements that were made in the documentary The Uncounted Enemy: A Vietnam Deception (1982). Westmoreland claimed that the documentary made him appear as if he had manipulated intelligence. The lawsuit, Westmoreland v. CBS, was later dropped after CBS issued a statement explaining they never intended to portray the general as disloyal or unpatriotic. During the proceedings, Wallace was hospitalized with what was diagnosed as exhaustion. His wife Mary forced him to go to a doctor, who diagnosed Wallace with clinical depression. He was prescribed an antidepressant and underwent psychotherapy. Out of a belief that it would be perceived as weakness, Wallace kept his depression a secret until he revealed it in an interview with Bob Costas on Costas' late-night talk show, Later.[43] In a later interview with colleague Morley Safer, he admitted having attempted suicide circa 1986.[44]

Wallace received a pacemaker more than 20 years before his death, and underwent triple bypass surgery in January 2008.[5] He lived in a care facility the last several years of his life.[5] In 2011, CNN host Larry King visited him and reported that he was in good spirits, but that his physical condition was noticeably declining.

Politics

[edit]Wallace considered himself a political moderate. He was a friend of Nancy Reagan and her family for over 75 years.[45] Fox News said, "He didn't fit the stereotype of the Eastern liberal journalist." Interviewed by his son on Fox News Sunday, he was asked if he understood why people feel disaffection toward mainstream news media. "They think they're wide-eyed commies; liberals," Mike replied, a notion he dismissed as "damned foolishness".[46]

In a 1979 interview with Mother Jones magazine, Wallace lamented the idea that he was regarded by peers as the "in-house conservative" at CBS News, saying he had "liberal inclinations" and had come from a family of "Roosevelt Democrats." However, covering Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew on the 1968 presidential campaign trail made him more sympathetic to their points of view, and Wallace developed positive relationships with both men, and was also close with Henry Kissinger and William F. Buckley. Nixon wanted Wallace to be his press secretary.[22]

Wallace rejected the notion that the United States was a structurally flawed society, citing his humble upbringing and later success (as well as the success of 60 Minutes) as proof the American Dream worked. He was critical of socialism and government intervention in the economy, calling the United Kingdom a "sad country to visit" due to its stagnating economy, which he blamed on Britain at the time being a "planned economy", and warned the United States would soon follow down the same path.[22]

Death

[edit]Wallace died at his residence in New Canaan, Connecticut, from natural causes on April 7, 2012.[5][47] The night after Wallace's death, Morley Safer announced his death on 60 Minutes. On April 15, 2012, a full episode of 60 Minutes aired that was dedicated to remembering Wallace's life.[48][49][50] He is buried at West Chop Cemetery in Tisbury, Massachusetts.[51]

Awards

[edit]In 1989, Wallace was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws from the University of Pennsylvania.[52] Wallace's professional honors included 21 Emmy Awards,[5] among them a report just weeks before the September 11 attacks for an investigation on the former Soviet Union's smallpox program and concerns about terrorism. He also won three Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University Awards, three George Foster Peabody Awards, a Robert E. Sherwood Award, a Distinguished Achievement Award from the University of Southern California School of Journalism, the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement,[53] and a Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award in the international broadcast category. In September 2003, Wallace received a Lifetime Achievement Emmy, his 20th.[citation needed] Most recently, on October 13, 2007, Wallace was awarded the University of Illinois Prize for Lifetime Achievement in Journalism.

- 1991: Paul White Award, Radio Television Digital News Association[54]

- 1999: Gerald Loeb Award for Network and Large-Market Television for an investigative piece on the international pharmaceutical industry[55]

Fictional portrayals

[edit]Wallace was played by actor Christopher Plummer in the 1999 feature film The Insider. The screenplay was based on the Vanity Fair article "The Man Who Knew Too Much" by Marie Brenner, which was about Wallace caving in to corporate pressure to kill a story about Jeffrey Wigand, a whistle-blower trying to expose Brown & Williamson's dangerous business practices in the manufacture of cigarettes. Wallace disliked his on-screen portrayal and maintained that he was in fact very eager to have Wigand's story aired in full.

Wallace was played by actor Stephen Rowe in the stage version of Frost/Nixon, but he was omitted from the screenplay of the 2008 film adaptation and thus the movie itself. In the 1999 American broadcast television movie Hugh Hefner: Unauthorized, Wallace is portrayed by Mark Harelik. In the film A Face in the Crowd (1957), Wallace portrayed himself. In 2020, Greg Dehm played Wallace in episode 6 of the second season of Manhunt, re-creating Wallace's 1996 interview on 60 Minutes with Richard Jewell, the security guard who discovered a bomb at Atlanta's Centennial Olympic Park in July 1996. In the film The Apprentice (2024), Wallace was portrayed by Stuart Hughes.

See also

[edit]- The 20th Century with Mike Wallace (A documentary television program)

- The Hate That Hate Produced (1959) – A television documentary produced by Mike Wallace and Louis Lomax

- The Mike Wallace Interview

- Profiles in Courage authorship controversy on The Mike Wallace Interview

- Mike Wallace Is Here, a 2019 biographical documentary film directed by Avi Belkin

- Westmoreland v. CBS – In which case Mr. Wallace is among the defendants

Further reading

[edit]Autobiographies

[edit]- Wallace, Mike; Gates, Gary Paul (1984). Close Encounters: Mike Wallace's Own Story. New York: William Morrow & Company Inc. ISBN 0-688-01116-0.

- Wallace, Mike; Gates, Gary Paul (2005). Between You and Me: A Memoir. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 1-4013-0029-4.

Biographies

[edit]- Rader, Peter (2012). Mike Wallace: A Life. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-0-312-54339-6..

Magazine Articles

[edit]- Cooper, Rand Richards (September 27, 2019). "From Muckraking to Clickbait: 'Mike Wallace Is Here'". Commonweal Magazine.

References

[edit]- ^ "Mike Wallace, the face of investigative reporting in America". CNN. 9 April 2012.

- ^ TruthTube1111 (25 May 2011). "Ayn Rand First Interview 1959 (Full)". Archived from the original on 2021-12-21 – via YouTube.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Someoddstuff (September 28, 2011). "Aldous Huxley interviewed by Mike Wallace: 1958 (Full)". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ CBS News (2012-04-15), Saying farewell to the extraordinary Mike Wallace, retrieved 2022-05-05

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Weiner, Tim (April 8, 2012). "Mike Wallace, CBS Pioneer of 60 Minutes, Dies at 93". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2012-08-10. Retrieved 2023-01-03.

- ^ Times of Israel: "CBS reporter Mike Wallace dead at 93 – Son of Jewish Russian immigrants had a career that spanned 60 years" by Ilan Ben Zion April 8, 2012

- ^ H.W. Wilson Company (1978). Current biography yearbook. H. W. Wilson Co. p. 418. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ^ Brozan, Nadine. "Chronicle", The New York Times, March 16, 1993. Retrieved February 5, 2008. "Mike Wallace is lending a hand to his old school, Brookline High School, at a benefit – unusual for a Massachusetts public school – in New York tomorrow evening. Mr. Wallace, class of '35, will interview the school's acting headmaster, Dr. Robert J. Weintraub, at a cocktail party that is expected to draw 60 or so Brookline graduates to the University Club on West 54th Street."

- ^ "Home – Zeta Beta Tau". Zeta Beta Tau. Archived from the original on 2011-03-01. Retrieved 2018-03-28.

- ^ "Interlochen Center for the Arts". www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on 2022-02-26. Retrieved 2017-05-09.

- ^ Dunning, John (1998). "Curtain Time". On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio (Revised ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 187–188. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ Dunning, op. cit., "The Green Hornet" pp. 297-299

- ^ Dunning, op. cit., "The Spike Jones Show" pp. 625=627

- ^ "Mike Wallace Got His Start In Radio: '60 Minutes' Veteran's career began as a news reader, voice on Lone Ranger". RadioWorld. April 9, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. and Iraqi Forces Launch Operation Swarmer; Interview With Mike Wallace". CNN. March 16, 2006.

- ^ The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows, 1946–present. Ballantine Books. 2003. p. 1116. ISBN 0-345-45542-8.

- ^ Brooks, Tim; Marsh, Earle (1999). The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows 1946-Present (7th ed.). New York: The Ballentine Publishing Group. p. 1114. ISBN 0-345-42923-0.

- ^ "Mike Wallace Packs Lot of Trade Interest In Second-Best Ratings". Variety. January 2, 1957. p. 18. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ Joseph, Peniel E. (2006). Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America. New York: Henry Holt and Company. pp. 21–23. ISBN 0-8050-7539-9.

- ^ a b "Barbra Streisand Archives – TV – P.M. East with Mike Wallace 1961–1962". barbra-archives.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2012-05-05.

- ^ Rebroadcast on CNN, Larry King Live during an interview with Mike Wallace.

- ^ a b c Klein, Jeffrey (October 1979). "Mike Wallace: The Mother Jones Interview". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2025-09-24.

- ^ "Minister Farrakhan on 60 Minutes with Mike Wallace". 5 August 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ "The Uncounted Enemy: A Vietnam Deception". Museum of Broadcast Communications. Archived from the original on 2002-10-02. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- ^ "Michigan Newsman Apologizes for Racist Remarks". Miami Herald. 1987-05-04. pp. 13A.

- ^ Rosenberg, Howard (February 10, 1990). "Is CBS News Guilty of Andy Rooney-Bashing?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ Thomas, Cal (1990-02-19). "In Andy Rooney Case, CBS Loses Enthusiasm for Free Speech". St. Paul Pioneer Press. pp. 11A.

- ^ Rader, Peter (2012). Mike Wallace: A Life. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4668-0225-4.

- ^ "Group Protests Mike Wallace as Commencement Speaker". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution: C/3. 1987-04-16.

- ^ Morganfield, Robbie (1987-05-01). "Veteran Journalist Mike Wallace, Calling Remarks He Made Six Years Ago "Arguably Racist," Plans To Apologize Saturday When He Speaks at the University of Michigan's Spring Commencement". USA Today.

- ^ Battaglio, Stephen (31 July 2018). "CBS allegations just the latest in long history of sexual harassment claims in network news". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2019-06-30.

- ^ Farrow, Ronan (2018-07-27). "Les Moonves and CBS Face Allegations of Sexual Misconduct". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 2019-06-30.

- ^ "'60 Minutes' Chief Jeff Fager Steps Down". The Hollywood Reporter. 12 September 2018. Retrieved 2019-06-30.

- ^ Windolf, Jim (2021-02-16). "Was '60 Minutes' TV's Most Toxic Workplace?". The New York Times. Retrieved 2025-09-24.

- ^ Mike Wallace Retiring From 60 Minutes, Broadcasting & Cable, March 14, 2006.

- ^ "Iranian Leader Opens Up – 60 Minutes". CBS News. 2006-08-13. Archived from the original on August 15, 2006. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ^ "Clemens drowns in hopelessness – MLB – Yahoo! Sports". Sports.yahoo.com. 7 January 2008. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ^ "Mike Wallace, on the Comeback". U.S. News & World Report. 2008-06-06. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ^ "The one big interview Mike Wallace never landed". USA Today. AP. March 22, 2006. Archived from the original on August 21, 2011. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- ^ Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk About Being Jewish By Abigail Pogrebin retrieved March 30, 2013

- ^ "In Memoriam: Peter Jon Wallace". Website of the Yale Class of 1964. Retrieved 2019-06-22.

- ^ Nelson, Valerie J. (July 22, 2010). "Buff Cobb dies; actress, theatrical producer was once married to Mike Wallace". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ a b Wallace, Mike (January 2002). "Mike Wallace on Coping with Depression (Mike Wallace's Darkest Hour)". Guideposts. Archived from the original on April 13, 2012.

- ^ "Mike Wallace Admits Suicide Attempt". Hollywood.com. 25 January 2013. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013.

- ^ "Reactions to the death of correspondent Mike Wallace". Fox News. April 8, 2012. Archived from the original on May 12, 2012.

- ^ "Famed CBS journalist Mike Wallace dies at 93". Fox News. April 8, 2012.

- ^ Safer, Morely. "Remembering Mike Wallace". CBS News. Archived from the original on April 8, 2012. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ Tanglao, Leezel. "Mike Wallace Dies". ABC News.

- ^ Hayes, Ashley (April 9, 2012). "Veteran newsman Mike Wallace dead at 93". CNN.

- ^ Silver, Stephen. "60 Minutes Says Goodbye to Mike Wallace". EntertainmentTell. www.technologytell.com. Archived from the original on 2012-04-18. Retrieved 2012-04-17.

- ^ Sigelman, Nelson (2012-07-18). "Family and friends attend Mike Wallace's burial in West Chop". Martha Vineyard Times. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ "1989 U. of Pennsylvania graduation program" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "Paul White Award". Radio Television Digital News Association. Archived from the original on 2013-02-25. Retrieved 2014-05-27.

- ^ "The media business: reporting prizes are announced". The New York Times. May 26, 1999. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

External links

[edit]- Mike Wallace at IMDb

- Mike Wallace collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Mike Wallace at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television

- Mike Wallace in Television in America: An Autobiography, a series by CUNY TV

- The Mike Wallace Interview — Archives of his New York interview show from the late 1950s in the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin (68 in total, some are audio-only)

- Mike Wallace (archived 2009) in The Museum of Broadcast Communications

- Mike Wallace, Interviewer: 'You and Me' on Fresh Air on NPR, November 8, 2005

- From Our Archives: One-on-One with Mike Wallace, The Saturday Evening Post, April 9, 2012

- Mike Wallace interview / William Waterway (1986) on Vimeo