Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mood swing

View on WikipediaThis article needs to be updated. (July 2021) |

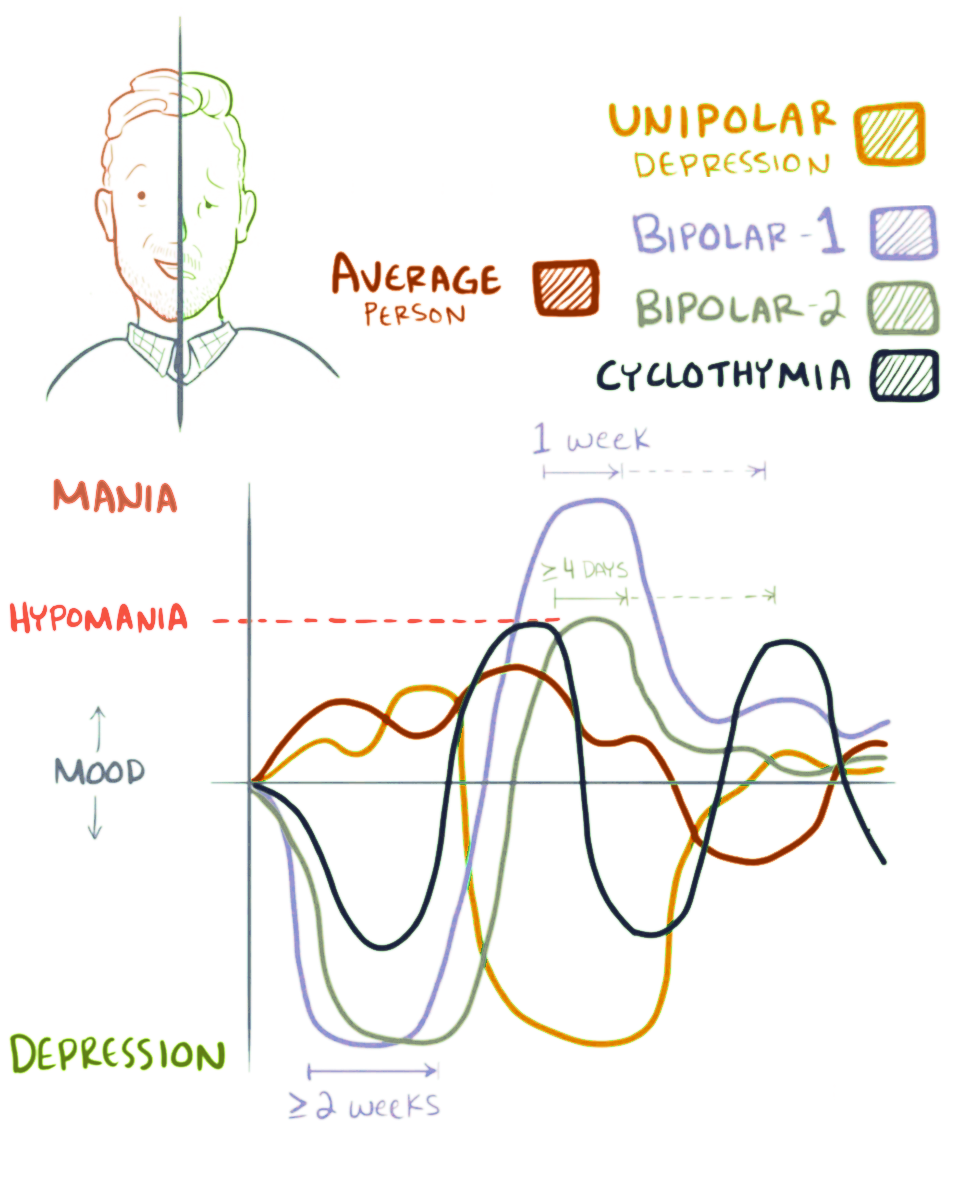

A mood swing is an extreme or sudden change of mood. Such changes can play a positive or a disruptive part in promoting problem solving and in producing flexible forward planning.[1] When mood swings are severe, they may be categorized as part of a mental illness, such as bipolar disorder, where erratic and disruptive mood swings are a defining feature.[2]

To determine mental health problems, people usually use charting with papers, interviews, or smartphone to track their mood/affect/emotion.[3][4] Furthermore, mood swings do not just fluctuate between mania and depression, but in some conditions, involve anxiety.[5][6]

Terminology

[edit]Definitions of the terms mood swings, mood instability, affective lability, or emotional lability are commonly similar, which describe fluctuating or oscillating of mood and emotions. But each has unique characteristics that are used to describe specific phenomena or patterns of oscillation.[7][8] Different from emotions or affect,[9] mood is associated with emotional responses without knowing the reason (being unaware).[10][11]

The dynamics of mood, mood patterns for long times are commonly erratic,[12] labile[13] or instable, also known as euthymic.[14] Although the term of mood swing is unspecific, it may be used to describe a pattern where mood goes down from positive to negative valency immediately (without delay in baseline) at specific periods.[15] And also generally have aperiodic patterns.[16][17] This is because mood dynamics are influenced by various factors which can magnify or lessen fluctuations,[18] such as when expectations become reality or not.[19] Other terms for describing patterns are episodic, periodic, cyclothymia, rapid cycling, mixed states, short episodes, soft spectrum,[20] diurnal variation, etc., although the definition of each term may be unclear.[21]

Overview

[edit]Speed and extent

[edit]Mood swings can happen any time at any place, varying from the microscopic to the wild oscillations of bipolar disorder,[22] so that a continuum can be traced from normal struggles around self-esteem, through cyclothymia, up to a depressive disease.[23] However, most people's mood swings remain in the mild to moderate range of emotional ups and downs.[24] The duration of bipolar mood swings also varies. They may last a few hours – ultrarapid – or extend over days – ultradian: clinicians maintain that only when four continuous days of hypomania, or seven days of mania, occur, is a diagnosis of bipolar disorder justified.[25] In such cases, mood swings can extend over several days, even weeks; these episodes may consist of rapid alternation between feelings of depression and euphoria.[26]

Characteristics

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2023) |

- Changing mood up and down without knowing the reason or external stimuli,[27] in various degrees, duration and frequent, from high mood (happy, elevated, irritated) to low mood (sad, depressed).[5][28]

- Sometimes it's mixed,[29] a combination between manic and depression symptoms[30] or similar with bittersweet experiences that last for a day.[31][32]

- Mood swings in normal people appear like "climate changing" at mild to moderate degree.[9][33] Thus, unless it happens at a moderate degree or more, some people need more high emotional intelligence[34] to recognize their mood change.[35]

- Mood swings in mental illness simply can be described by generalized complexity[36] based on mood dynamics (patterns that characterize the oscillation) like intensity (mild, moderate, severe), duration (days, weeks, years), average mood and other features, such as:[37][38]

- Mood swings in cyclothymia: Mood swings occur episodically and aperiodic within 2 years or more at a moderate degree and frequently.[39] Characterized by coexisting with anxiety, persistence, rapid shift, intense, impulsive,[40] heightened by sensitivity and reactivity to external stimuli.[41]

- Mood swings in bipolar II: Episodic,[42] hypomanic (severe degree) episodes occur continuously for 4 days,[30] depression episodes for weeks,[43] and sometimes erratic episodes at moderate degree in between episodes.[44]

- Mood swings in bipolar I: Episodic,[42] manic episodes (severe degree) occur continuously for 7 days,[30] depressive episodes for weeks,[45][46] and sometimes erratic episodes at moderate degree in between episodes.[30] Alterations in bipolar I and II can be rapid cyclic, which means changes of mood happen 4 times or more within a year.[47] Symptoms of manic and hypomanic episodes are similar between bipolar I and bipolar II, just different in degree of intensity.[48]

- Mood swings in Premenstrual symptoms (PMS): Episodically at mild to severe degree in the menses period, occur gradually or rapidly,[49] start 7 days before and decrease at the onset of menses.[50] Characterized by angry outbursts, depression, anxiety, confusion, irritability or social withdrawal.[51]

- Mood swings in borderline personality disorder (BPD): Mood changes erratically with episodic mood swings.[52] Mood swings fluctuate in rapid shifts for hours or days, not persistent, sensitive and heightened negative mood (e.g. irritability) by external stimuli.[53][54] Mood appears in the form of high intensity of irritability,[55][56] anxiety,[57] and moderate degree depression (characterized by hostility, anger towards self, loneliness, isolation, related with relationships, emptiness or boredom).[58][59]

- Mood swings in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) : Mood changes erratically and mood swings occur episodically, sometimes several times a day in rapid shifts.[60][61] Characterized by a mild to moderate degree of irritability,[62] related to the environment, impulsiveness (impatience to get rewards).[63] In adult ADHD, high mood appears as excitement and low mood appears as boredom.[60]

- Mood swings in schizophrenia: Although schizophrenia has flat emotions,[64] a study in 2021 based on ALS-SF measures, Margrethe Collier et al., found that the score pattern of schizophrenia is similar to bipolar I.[65] The alteration being related to delusions or hallucinations,[66] mood changes that occur internally may be difficult to express externally (blunt affect),[67] and heightened by external stimuli.[68]

- Mood swings in major depressive disorder (MDD): Various mood patterns,[69] and mood changes erratically.[37] Mood swings occur episodically and fluctuate in moderate high mood and severe low mood.[70][71] Characterized by having high negative affect (bad mood) most of the time, particularly in melancholic subtype.[72] And also positive diurnal variation mood (bad mood in the morning, good mood in the evening),[73] sensitivity to negative stimulation and mixed symptoms in some people, etc.[74][75]

- Mood swings in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Mood changes erratically[76] with episodic mood swings rising in the period of recovery process.[77][78] Characterized by temporary fluctuations in negative affect (anxiety, irritability, shame, guilt) and self-esteem, reactive to environmental reminders,[79] difficulty to control emotions,[80] hyperarousal symptoms, etc.[81][82]

Causes

[edit]There can be many different causes for mood swings. Some mood swings can be classified as normal/healthy reactions, such as grief processing, adverse effects of substances/drugs, or a result of sleep deprivation. Mood swings can also be a sign of psychiatric illnesses in the absence of external triggers or stressors.

Changes in a person's energy level, sleep patterns, self-esteem, sexual function, concentration, drug or alcohol use can be signs of an oncoming mood disorder.[83]

Other major causes of mood swings (besides bipolar disorder and major depression) include diseases/disorders which interfere with nervous system function. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), epilepsy,[84] and autism spectrum are three such examples.[85][86]

The hyperactivity sometimes accompanied by inattentiveness, impulsiveness, and forgetfulness are cardinal symptoms associated with ADHD. As a result, ADHD is known to bring about usually short-lived (though sometimes dramatic) mood swings. The communication difficulties associated with autism, and the associated changes in neurochemistry, are also known to cause autistic fits (autistic mood swings).[87] The seizures associated with epilepsy involve changes in the brain's electrical firing, and thus may also bring about striking and dramatic mood swings.[84] If the mood swing is not associated with a mood disorder, treatments are harder to assign. Most commonly, however, mood swings are the result of dealing with stressful and/or unexpected situations in daily life.

Degenerative diseases of the human central nervous system such as Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis, and Huntington's disease may also produce mood swings.[88] Celiac disease can also affect the nervous system and mood swings can appear.[89]

Not eating on time can contribute, or eating too much sugar, can cause fluctuations in blood sugar, which can cause mood swings.[90][91]

Brain chemistry

[edit]If a person has an abnormal level of one or several of certain neurotransmitters (NTs) in their brain, it may result in having mood swings or a mood disorder.[92] Serotonin is one such neurotransmitter that is involved with sleep, moods, and emotional states. A slight imbalance of this NT could result in depression. Norepinephrine is a neurotransmitter that is involved with learning, memory, and physical arousal. Like serotonin, an imbalance of norepinephrine may also result in depression.[93]

List of conditions known to cause mood swings

[edit]- Bipolar disorder[94][95] or cyclothymia: Bipolar disorder is a mood disorder with characteristics of mood swings from hypomania or mania to depression. While cyclothymia is a lower degree of bipolar disorder.[96] In 2022, ENIGMA Bipolar Disorder Working Group found that people with bipolar disorder have smaller subcortical volumes, lower cortical thickness and altered white matter integrity,[97][98] which one of the functions is for emotion processing.[99]

- Anabolic steroid abuse:[100] Anabolic steroids are synthetic derivatives of testosterone. Used for treatment of male hypogonadism or delayed puberty,[101] stimulating muscle growth,[102] as well as treating impotence, and AIDS.[103] Studies found that overusing anabolic-androgenic steroids can cause mood swings, impulsive, and aggressive behavior.[104] This behavior is associated with decreased emotion regulation systems such as the frontal cortex, temporal, parietal, and occipital.[105] Studies also found that using anabolic-androgenic steroids can cause neuronal changes and death in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, thus symptoms of sleep and mood disorder occur.[106]

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): ADHD is known as a disorder with difficulty keeping control of attention, hyperactivity, frequently changing focus and losing interest[107] and also hyperfocus when doing something interesting or pleasurable tasks.[108] Mood dysregulation may be caused by distraction when absorbed in pleasurable tasks.[109][110] Another contribution to mood swings is lower brain activity in the prefrontal cortex (PFC),[111] orbitofrontal cortex (OFC),[112] increased size of the hippocampus and decreasing size of the amygdala in some people.[113] Abnormalities in these parts of the brain can cause disturbance in attention, motivation, mood, and behavioral inhibition.[114]

- Autism or other pervasive developmental disorder: Autism is a neurological and development disorder with symptoms such as lack of social skills, restricted repetitive behaviors, hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input, etc.[115] Abnormal sensory processing is one of the reasons for mood swings in autism.[116] Studies in 2015 found that in autism, the brain becomes overactivated in limbic areas, primary sensory cortices, and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), which functions for emotional and sensory processing. Studies found too, that the brain in autism has decreased connectivity between the amygdala and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, increased amygdala reactivity, and reduced prefrontal response which contribute to emotion dysregulation.[117][118]

- Borderline personality disorder: It has been theorized that borderline personality disorder comes from lack of ability to endure, learn[119] and overcome negative events.[120] People with BPD commonly have difficulty in relationships,[121] which is associated with a tendency to anger-outbursts, judgment[122] or expecting how others behave.[123] Emotion dysregulation may be as a result of lack of interpersonal skills such as knowledge about emotions and how to control them, especially with intense emotions.[124] Mostly, people with BPD use maladaptive emotion regulations like self-criticism, thought suppression, avoidance, and alcohol, which may trigger more mood disruption.[125][126][127]

- Dementia, including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and Huntington's disease: Dementia is known as a decreasing brain function disease that affects older people.[128] In Alzheimer's disease, mood dysregulation can be caused by decreasing function of emotional regulation, salience, cholinergic, GABAergic, and dopaminergic function.[128] Parkinson's disease can generate mood swings and mood dysregulation such as depression, low self worth, shame and worry about the future caused by cognitive and physical problems.[129] And in Huntington's disease, common mood swings occur as a result of psychosocial, cognitive deficits, neuropsychiatric and biological factors.[130]

- Dopamine dysregulation syndrome: Dopamine dysregulation syndrome is an effect of abusing Parkinson's disease drugs to decrease motor and non-motor syndromes, which result in mania, violent behavior, and depression when withdrawal.[131] Mood dysregulation from dopamine dysregulation syndrome occurs as a result of changes in the neurotransmitter systems such as disturbance in the dopaminergic reward system.[132][131]

- Epilepsy: Epilepsy is an abnormal brain activity disease marked with seizures. Seizures occur because hypersynchronous and hyperexcitability of neurons, in other words, too much neural activity and excitability at the same time.[133] Mood swings commonly appear before, during, after a seizure and during treatment.[134] Studies found that seizures contribute to decreased function of emotions and mood processing as a consequence of abnormal neurogenesis and damaged neuron connections in the hippocampus and amygdala.[133] Experiencing a seizure can cause mood swings caused by depression, anxiety, or worry about life being threatened. Another source of mood change comes from anticonvulsant drugs for epilepsy, like phenobarbital for increasing brain inhibitors or antiglutamatergic for decreasing brain activity which generates depression, cognitive dysfunction, sedation or mood lability.[135]

- Hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism: Hypo- and hyperthyroidism is an endocrine disease caused by low or excessive production of thyroid hormone. Abnormal thyroid hormone can affect mood,[136] although the correlation between thyroid hormone and mood disorder is still not known.[137]

- Intermittent explosive disorder: Intermittent explosive disorder is frequent rage that occurs spontaneous, uncontrolled, unproportioned and not persistent.[138][139] This short duration of alternate mood occurs in the form of aggression verbally or physically towards people or property, sometimes followed by regret, shame and guilt after an act which might generate depression symptoms.[140] Impulsive behavior in IED can be associated with hyperactivity in brain regions for regulating and emotional expression, such as the amygdala, insula, and orbitofrontal area.[141]

- Menopause:[142] Menopause in women commonly happens at age 52. One factor that causes mood disturbance is fluctuation of milieu hormones[143] including sex steroids, growth hormones, stress hormones, etc.[144][145]

- Major depression: Major depression is a disorder with symptoms such as feelings of sadness, loss of interest, emptiness[146] and, for some people, mixed with irritability, mental overactivity, and behavioral overactivity.[147] Development of irritability or anger may result from personality traits like narcissistic or coping strategies to avoid looking sad, worthless, or frustrated.[148]

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: Obsessive compulsive disorder is marked with obsessions and compulsions about something that causes life distress and dysfunction.[149] Alteration of mood and feeling discomfort such as shame, guilt or anxiety may occur caused by intrusive thoughts, fear, urge,[150] and fantasy.[151]

- Pathological demand avoidance

- Post traumatic stress disorder: Post-traumatic stress disorder is a disorder which is associated with frequently being disturbed by flashback memories and being haunted by feelings of fear and horror in the past. This contributes to the alteration of mood that occurs after a traumatic event happens, such as depression, outbursts of anger, self-destructive behaviors, and feelings of shame.[152][153]

- Pregnancy: Women commonly experience mood swings during the pregnancy and the postpartum period. Hormone changes, stress and worry may be the reasons for changes of mood.[154]

- Premenstrual syndrome:[155] Women experience premenstrual syndrome like physical pains, mood swings, irritability or depression[156] in a few days until 2 weeks of their period with different intensity.[157] Furthermore, 4% to 14% of women experience severe PMS or premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), which can decrease life quality.[158] Despite the reason mood dysregulation in PMS is still unclear, Studies found that mood dysregulation is related with drop in progesterone concentrations, disruption of serotonergic transmission, GABAergic, stress, body-mass index, and traumatic events.[157]

- Schizoaffective disorder: Mood swings in schizoaffective disorder are caused by mixed symptoms between schizophrenia and mood disorder.[159]

- Schizophrenia: Schizophrenia is a disorder with symptoms of delusions, hallucinations, mood dysregulation, etc.[160] Mood changes may be generated from hallucinations and delusions[161] which cause anger,[162][163] paranoia,[164] and shame.[165]

- Seasonal affective disorder: Seasonal affective disorder is depression which occurs during some seasons (commonly in winter), then manic or hypomanic episodes in the other season and that happens every year.[166] These fluctuating moods appear in the form of anger attacks with depression[167] and occur from season to season, also known as seasonal mood swings.[168]

- XXYY syndrome: XXYY syndrome is a rare type of sex chromosome aneuploidies (SCAs). XXYY syndrome contributes to abnormal neurodevelopment and psychiatric diseases which can cause mood disorders.[169][170]

Treatment

[edit]It's part of human nature's mood going up and down caused by various factors.[171] Individual strength,[172] coping skill or adaptation ability,[173] social support[174] or another recovery model might determine whether mood swings will create disruption in life or not.[175][176]

Cognitive behavioral therapy recommends using emotional dampeners to break the self-reinforcing tendencies of either manic or depressive mood swings.[177] Exercise, treats, seeking out small (and easily attainable) triumphs, and using vicarious distractions like reading or watching TV, are among the techniques found to be regularly used by people in breaking depressive swings.[178] Learning to bring oneself down from grandiose states of mind, or up from exaggerated shame states, is part of taking a proactive approach to managing one's own moods and varying sense of self-esteem.[179]

Behavioral activation is a component of CBT that can break the cycle (depression leads to inactivity, inactivity leads to depression).[180] This may rely on individual strengths to "cold start" the reward system.[181]

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT): Another manifestation of mood swing is irritability, which can lead to elation, anger or aggression.[182] DBT has a lot of coping skills that can be used for emotion dysregulation, such as mindfulness with the "wise mind"[183] or emotion regulation with opposite action.[184][185]

Emotion regulation therapy (ERT) has a package of mindful emotion regulation skills (e.g., attention regulation skills, metacognitive regulation skills, etc.) that can be handy to have when mood swings happen.[186]

Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy can be used to regulate life rhythm when mood swings happen frequently and disrupt the rhythm of life.[187] Episodes of mood disorder often liberate people from daily routines by making a mess of sleep schedules, social interaction,[188][189] or work and causing irregular circadian rhythms.[190]

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) has a function to increase psychological flexibility by learning to assess present experience or be mindful, accept everything internally or externally, commit action to move toward personal recovery, etc.[191]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Peter Salovey et al, Emotional Intelligence (2004) p. 1974

- ^ "BBC Science – When does your mental health become a problem?". BBC Science. 19 April 2013. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ Faurholt-Jepsen, Maria; Munkholm, Klaus; Frost, Mads; Bardram, Jakob E.; Kessing, Lars Vedel (15 January 2016). "Electronic self-monitoring of mood using IT platforms in adult patients with bipolar disorder: A systematic review of the validity and evidence". BMC Psychiatry. 16 7. doi:10.1186/s12888-016-0713-0. ISSN 1471-244X. PMC 4714425. PMID 26769120.

Electronic self-monitoring of mood was considered valid compared to clinical rating scales for depression in six out of six studies, and in two out of seven studies compared to clinical rating scales for mania.

- ^ Trull, Timothy J.; Solhan, Marika B.; Tragesser, Sarah L.; Jahng, Seungmin; Wood, Phillip K.; Piasecki, Thomas M.; Watson, David (2008). "Affective instability: Measuring a core feature of borderline personality disorder with ecological momentary assessment". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 117 (3): 647–661. doi:10.1037/a0012532. ISSN 1939-1846. PMID 18729616.

Measuring and characterizing the experience of affective instability have proved challenging, however. Traditional measures of affective instability rely on respondents' retrospective recall and subjective assess-ment of affective variability or reactivity on interview or questionnaire items.

- ^ a b Harvey, Philip D.; Greenberg, Barbara R.; Serper, Mark R. (1989). "The affective lability scales: Development, reliability, and validity". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 45 (5): 786–793. doi:10.1002/1097-4679(198909)45:5<786::AID-JCLP2270450515>3.0.CO;2-P. PMID 2808736.

A self-report measure of changeable affect was developed, with a goal of identification of patterns of instability in mood. Scales measuring lability in anxiety, depression, anger, and hypomania, and labile shifts between anxiety and depression and hypomania and depression were constructed. These scales were then evaluated for internal consistency, retest reliability, score stability ...

- ^ Contardi, Anna; Imperatori, Claudio; Amati, Italia; Balsamo, Michela; Innamorati, Marco (2018). "Assessment of Affect Lability: Psychometric Properties of the ALS-18". Frontiers in Psychology. 9 427. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00427. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 5885065. PMID 29651267.

To measure affect lability, Harvey et al. (1989) developed the Affective Lability Scales (ALS), a 58-item questionnaire measuring changeability among euthymia and four affect states (i.e., depression, elation, anger, and anxiety).

- ^ Ketal, R. (1975). "Affect, mood, emotion, and feeling: semantic considerations". American Journal of Psychiatry. 132 (11): 1215–1217. doi:10.1176/ajp.132.11.1215. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 1166902.

...the use and definitions of the terms "affect," "mood," "emotion," and "feeling" in some classical and contemporary works of psychiatry and psychology. He concludes that these words refer to distinct pscychological phenomena and suggests that they be used clearly and carefully to facilitate communication about emotions.

- ^ Broome, M. R.; Saunders, K. E. A.; Harrison, P. J.; Marwaha, S. (2015). "Mood instability: significance, definition and measurement". The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science. 207 (4): 283–285. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.114.158543. ISSN 1472-1465. PMC 4589661. PMID 26429679.

The literature spans psychiatry, psychology and neuroscience, and multiple terms are used to describe the same, or related phenomena, including affective instability, emotional dysregulation, mood swings, emotional impulsiveness and affective lability. Collating the main overlapping dimensions, definitions, and their measurement scales, a recent systematic review proposed that mood instability is 'rapid oscillations of intense affect, with a difficulty in regulating these oscillations or their behavioural consequences'.

- ^ a b Manjunatha, Narayana; Khess, Christoday Raja Jayant; Ram, Dushad (2009). "The conceptualization of terms: 'Mood' and 'affect' in academic trainees of mental health". Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 51 (4): 285–288. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.58295. ISSN 1998-3794. PMC 2802377. PMID 20048455.

One would conclude from the above italic sentences of Fish that affect is a sudden exacerbation of emotion, and mood is also the emotional state prevailing at any given time, in other words, both mood and affect are short-term emotional tone (However, these confusing lines are deleted in the new edition of Fish's clinical psychopathology).

- ^ "APA Dictionary of Psychology". dictionary.apa.org. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

Moods differ from emotions in lacking an object; for example, the emotion of anger can be aroused by an insult, but an angry mood may arise when one does not know what one is angry about or what elicited the anger.

- ^ Leaberry, Kirsten D.; Walerius, Danielle M.; Rosen, Paul J.; Fogleman, Nicholas D. (2020), "Emotional Lability", Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1319–1329, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-24612-3_510, ISBN 978-3-319-24610-9, S2CID 241582879." Previous literature suggests that mood often has a greater duration and is associated with an internal state value, whereas emotions are sudden and intense and are associated with greater environmental information value (Larsen et al. 2000).

- ^ Kahmann, Daan (2022) Emotion dynamics in Tibetan monks and healthy Westerners. Bachelor's Thesis, Artificial Intelligence.university of groningen."Emotions can be very turbulent and are constantly changing."

- ^ Klinkman, Michael S. (2007). "A whole new world: complexity theory and mood variability in mental disorders". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 9 (3): 180–182. doi:10.4088/pcc.v09n0302. ISSN 1523-5998. PMC 1911185. PMID 17632649.

Four of 5 normal controls displayed a circadian mood pattern with chaotic dynamics.

- ^ Fava, Giovanni A.; Bech, Per (27 November 2015). "The Concept of Euthymia". Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 85 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1159/000441244. ISSN 0033-3190. PMID 26610048. S2CID 29087528.

When a patient, in the longitudinal course of mood disturbances, no longer meets the threshold of a disorder such as depression or mania, as assessed by categorical methods resulting in diagnostic criteria or by cutoff points in the dimensional measurement of rating scales, he or she is often labeled as euthymic.

- ^ "APA Dictionary of Psychology". dictionary.apa.org. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

a nonspecific term for any oscillation in mood, particularly between feelings of happiness and sadness.

- ^ Katerndahl, David; Ferrer, Robert; Best, Rick; Wang, Chen-Pin (2007). "Dynamic patterns in mood among newly diagnosed patients with major depressive episode or panic disorder and normal controls". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 9 (3): 183–187. doi:10.4088/pcc.v09n0303. ISSN 1523-5998. PMC 1911176. PMID 17632650.

Complexity of symptoms or behaviors in an individual is often characterized by the dynamics of the individual's longitudinal patterns. While periodic/linear temporal patterns are predictable in both trajectory and pattern, chaotic patterns are predictable in pattern only. Random dynamics are predictable in neither trajectory nor pattern.

- ^ Cowdry, R. W.; Gardner, D. L.; O'Leary, K. M.; Leibenluft, E.; Rubinow, D. R. (1991). "Mood variability: a study of four groups". American Journal of Psychiatry. 148 (11): 1505–1511. doi:10.1176/ajp.148.11.1505. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 1928464.

The visual analog scale can capture patterns of mood and mood variability thought to be typical of these diagnostic groups. Mood disorders differ not only in the degree of abnormal mood but also in the pattern of mood variability, suggesting that mechanisms regulating mood stability may differ from those regulating overall mood state.

- ^ Pessiglione, Mathias; Heerema, Roeland; Daunizeau, Jean; Vinckier, Fabien (1 April 2023). "Origins and consequences of mood flexibility: a computational perspective". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 147 105084. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2023.105084. ISSN 0149-7634. PMID 36764635. S2CID 256666316.

We typically have little control over fluctuations between episodes of good and bad mood. In most cases, we also have little understanding of the causal factors driving our mood fluctuations, contrary to emotional reactions that are circumscribed to a specific trigger and limited to a short duration.

- ^ Eldar, Eran; Rutledge, Robb B.; Dolan, Raymond J.; Niv, Yael (1 January 2016). "Mood as Representation of Momentum". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 20 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2015.07.010. ISSN 1364-6613. PMC 4703769. PMID 26545853.

The main conclusion of the study was that happiness depends not on how well things are going (in terms of cumulative earnings) but whether they are going better than expected.

- ^ Perugi, Giulio; Akiskal, Hagop S. (2002). "The soft bipolar spectrum redefined: focus on the cyclothymic, anxious-sensitive, impulse-dyscontrol, and binge-eating connection in bipolar II and related conditions". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 25 (4): 713–737. doi:10.1016/s0193-953x(02)00023-0. ISSN 0193-953X. PMID 12462857.

The bipolar II spectrum represents the most common phenotype of bipolarity. Numerous studies indicate that in clinical settings this soft spectrum might be as common--if not more common than--major depressive disorders.

- ^ Bowen, Rudy; Clark, Malin; Baetz, Marilyn (1 March 2004). "Mood swings in patients with anxiety disorders compared with normal controls". Journal of Affective Disorders. 78 (3): 185–192. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00304-X. ISSN 0165-0327. PMID 15013242.

Difficulties with measurement, and unclear definitions for terms like cyclothymia, rapid cycling, mixed states, short episodes, and soft spectrum have contributed to the uncertainty (Akiskal et al., 2000, Blacker and Tsuang, 1992, Cassano et al., 1999, Ghaemi et al., 2001).

- ^ Sigmund Freud, Civilization, Society and Religion (PFL 12) p. 164

- ^ Otto Fenichel, The Psychoanalytic Theory of Neurosis (1946) p. 406

- ^ Daniel Goleman (1995). Emotional Intelligence: Why it Can Matter More Than IQ. Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7475-2830-2. ASIN 0747528306.

- ^ S, Nassir Ghaemi, Mood Disorder (2007) p. 243-4

- ^ Hockenbury, Don and Sandra (2011). Discovering Psychology Fifth Edition. New York, NY: Worth Publishers. p. 549. ISBN 978-1-4292-1650-0.

- ^ Lischetzke, Tanja (2014), "Mood", in Michalos, Alex C. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 4115–4119, doi:10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_1842, ISBN 978-94-007-0753-5."Moods are affective states that are diffuse and unfocused, that is, not directed toward a specific object. They are continually present (tonic) and shape the background of our moment-moment experience, but fluctuate over time."

- ^ CAMH Bipolar Clinic Staff(2013)."Bipolar disorder:an information guide".camph:Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.www.camh.ca."Everyone has ups and downs in mood. Feeling happy, sad and angry is normal...Their moods may have nothing to do with things going on in their lives."

- ^ Janiri, Delfina; Conte, Eliana; De Luca, Ilaria; Simone, Maria Velia; Moccia, Lorenzo; Simonetti, Alessio; Mazza, Marianna; Marconi, Elisa; Monti, Laura; Chieffo, Daniela Pia Rosaria; Kotzalidis, Georgios; Janiri, Luigi; Sani, Gabriele (29 March 2021). "Not Only Mania or Depression: Mixed States/Mixed Features in Paediatric Bipolar Disorders". Brain Sciences. 11 (4): 434. doi:10.3390/brainsci11040434. ISSN 2076-3425. PMC 8065627. PMID 33805270.

DSM-5 introduced the "with mixed features" specifier, which could apply to any type of episode of BD and major depressive disorder (MDD).

- ^ a b c d Fava, Giovanni A.; Guidi, Jenny (2020). "The pursuit of euthymia". World Psychiatry. 19 (1): 40–50. doi:10.1002/wps.20698. ISSN 1723-8617. PMC 7254162. PMID 31922678.

Patients with bipolar disorder spend about half of their time in depression, mania or mixed states22. The remaining periods are defined as euthymic23, 24, 25, 26, 27. However, considerable fluctuations in psychological distress were recorded in studies with longitudinal designs, suggesting that the illness is still active in those latter periods, even though its intensity may vary28. It is thus questionable whether subthreshold symptomatic periods truly represent euthymia28....This definition of euthymia, because of its intertwining with mood stability, is substantially different from the concept of eudaimonic well‐being, that has become increasingly popular in positive psychology

- ^ Larsen, Jeff T.; McGraw, A. Peter; Cacioppo, John T. (2001). "Can people feel happy and sad at the same time?". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 81 (4): 684–696. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.4.684. ISSN 1939-1315. PMID 11642354.

Though mixed feelings may be uncommon, they might often have important consequences (e.g., for health).

- ^ Larsen, Jeff T.; Hershfield, Hal E.; Cazares, James L.; Hogan, Candice L.; Carstensen, Laura L. (2021). "Meaningful endings and mixed emotions: The double-edged sword of reminiscence on good times". Emotion. 21 (8): 1650–1659. doi:10.1037/emo0001011. ISSN 1931-1516. PMC 8817627. PMID 34591508.

Indeed, college students are more likely to report mixed emotions of happiness and sadness on the day that they move out of their freshmen dorm and on their graduation day than on typical days.

- ^ Larson, R.; Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Graef, R. (1980). "Mood variability and the psychosocial adjustment of adolescents". Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 9 (6): 469–490. doi:10.1007/BF02089885. ISSN 0047-2891. PMID 24318310. S2CID 5068051.

The findings confirm that adolescents experience wider and quicker mood swings, but do not show that this variability is related to stress, lack of personal control, psychological maladjustment, or social maladjustment within individual teenagers.

- ^ Okoronkwo, Valentine (29 November 2022). "39 Best Emotional Intelligence Statistics To Know In 2022". Passive Secrets. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

Only about 36% of people in the world are emotionally Intelligent... 54% of the U.S. population are emotionally aware.

- ^ Wilhelm, Peter & Schoebi, Dominik. (2007). Assessing Mood in Daily Life Structural Validity, Sensitivity to Change, and Reliability of a Short-Scale to Measure Three Basic Dimensions of Mood. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 23. 258-. 10.1027/1015-5759.23.4.258."Moods can be consciously experienced as soon as they gain the focus of our attention, and are then characterized by the predominance of certain subjective feelings."

- ^ Durstewitz, Daniel; Huys, Quentin J.M.; Koppe, Georgia (2020). "Psychiatric Illnesses as Disorders of Network Dynamics". Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging. 6 (9): 865–876. arXiv:1809.06303. doi:10.1016/j.bpsc.2020.01.001. PMID 32249208. S2CID 52288970.

Mental illnesses are highly complex, temporally dynamic phenomena (1). Variables across a vast range of timescales – from milliseconds to generations – and levels – from subcellular to societal – interact in complex manners to result in the dynamic, rich and extraordinarily heterogeneous temporal trajectories that are characteristic of the personal and psychiatric histories evident in mental health services across the world.

- ^ a b van Genugten, Claire. (2022). Measurement innovation: studies on smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment in depression. VU Research Portal.ISBN 978-94-93270-96-1."Mood dynamics are the patterns that characterize fluctuations in a person's mood [64]. Mood dynamics are often operationalized by a combination of "mood variability" and "emotional inertia" [65,66].

- ^ van Genugten, Claire R.; Schuurmans, Josien; Hoogendoorn, Adriaan W.; Araya, Ricardo; Andersson, Gerhard; Baños, Rosa M.; Berger, Thomas; Botella, Cristina; Cerga Pashoja, Arlinda; Cieslak, Roman; Ebert, David D.; García-Palacios, Azucena; Hazo, Jean-Baptiste; Herrero, Rocío; Holtzmann, Jérôme (17 March 2022). "A Data-Driven Clustering Method for Discovering Profiles in the Dynamics of Major Depressive Disorder Using a Smartphone-Based Ecological Momentary Assessment of Mood". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 13 755809. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.755809. ISSN 1664-0640. PMC 8968132. PMID 35370856.

- ^ Miklowitz, D. J., Gitlin, M. J. (2015). Clinician's Guide to Bipolar Disorder. Amerika Serikat: Guilford Publications."The mood swings of individuals with cyclothymia occur most of the time (in the DSM-5 definition, no more than 2 consecutive months have been symptom-free within a 2-year period) and never exhibit the number of symptoms or the length of ..."

- ^ Rhoads, J. (2021). Clinical Consult to Psychiatric Mental Health Management for Nurse Practitioners. Amerika Serikat: Springer Publishing Company."Mood changes in cyclothymic disorder can be abrupt and unpredictable, of short duration, and with infrequent euthymic episodes."

- ^ Perugi, Giulio; Hantouche, Elie; Vannucchi, Giulia (2017). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Cyclothymia: The "Primacy" of Temperament". Current Neuropharmacology. 15 (3): 372–379. doi:10.2174/1570159X14666160616120157. ISSN 1875-6190. PMC 5405616. PMID 28503108.

Cyclothymia is characterized by early onset, persistent, spontaneous and reactive mood fluctuations, associated with a variety of anxious and impulsive behaviors, resulting in a very rich and complex clinical presentation. Current diagnostic criteria for cyclothymic disorder (DSM-5 and ICD-10), emphasizing only episodic mood symptoms, may be misleading both from diagnostic and therapeutic point of views.

- ^ a b Holmes, E A; Bonsall, M B; Hales, S A; Mitchell, H; Renner, F; Blackwell, S E; Watson, P; Goodwin, G M; Di Simplicio, M (26 January 2016). "Applications of time-series analysis to mood fluctuations in bipolar disorder to promote treatment innovation: a case series". Translational Psychiatry. 6 (1): e720. doi:10.1038/tp.2015.207. ISSN 2158-3188. PMC 5068881. PMID 26812041.

A time-series approach allows comparison of mood instability pre- and post-treatment. Figure 1

- ^ Tondo, Leonardo; Vázquez, Gustavo H.; Baldessarini, Ross J. (2017). "Depression and Mania in Bipolar Disorder". Current Neuropharmacology. 15 (3): 353–358. doi:10.2174/1570159X14666160606210811. ISSN 1875-6190. PMC 5405618. PMID 28503106.

As expected, episodes of depressions were much longer than manias, but episode-duration did not differ among BD diagnostic types: I, II, with mainly mixed-episodes (BD-Mx), or with psychotic features (BD-P)...A total of 56.8% of subjects could be characterized for major course-patterns as either DMI or MDI, which occurred in similar proportions for each type. As expected, depressive episodes averaged 5.2 months

- ^ Gottschalk, A.; Bauer, M. S.; Whybrow, P. C. (1995). "Evidence of chaotic mood variation in bipolar disorder". Archives of General Psychiatry. 52 (11): 947–959. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950230061009. ISSN 0003-990X. PMID 7487343.

These studies indicate that mood in patients with bipolar disorder is not truly cyclic for extended periods. Nonetheless, self-rated mood in bipolar disorder is significantly more organized than self-rated mood in normal subjects and can be characterized as a low-dimensional chaotic process. This characterization of the dynamics of bipolar disorder provides a unitary theoretical framework that can accommodate neurobiologic and psychosocial data and can reconcile existing models for the pathogenesis of the disorder. Furthermore, consideration of the dynamical structure of bipolar disorder may lead to new methods for predicting and controlling pathologic mood.

- ^ Last, C. G. (2009). When Someone You Love Is Bipolar: Help and Support for You and Your Partner. Ukraina: Guilford Publications."Research indicates that bipolar II depressions persist for longer periods of time than bipolar I depressions, nearly twice as long (1 year versus 6 months)."

- ^ Solomon, David A.; Fiedorowicz, Jess G.; Leon, Andrew C.; Coryell, William; Endicott, Jean; Li, Chunshan; Boland, Robert J.; Keller, Martin B. (2013). "Recovery from multiple episodes of bipolar I depression". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 74 (3): e205–211. doi:10.4088/JCP.12m08049. ISSN 1555-2101. PMC 3837577. PMID 23561241.

The median duration of major depressive episodes was 14 weeks, and over 70% recovered within 12 months of onset of the episode. The median duration of minor depressive episodes was 8 weeks, and approximately 90% recovered within 6 months of onset of the episode...An early report from this study examined 66 participants with bipolar I followed for up to 5 years, and found that the median time to recovery from the first two prospectively observed episodes of major depression was 20 weeks and 24 weeks.16 A subsequent report described 82 participants with bipolar I followed for 10 years; the median duration of major and minor depressive episodes were 12 and 5 weeks, respectively.17

- ^ Fink, C., Kraynak, J. (2011). Bipolar Disorder For Dummies. Amerika Serikat: Wiley."Rapid cycling isn't a separate type of bipolar disorder, but your doctor may use the label to describe a particular subtype of Bipolar I or II. To qualify as a rapid-cycling sufferer, you must experience the following: You must ..."

- ^ Clinical Handbook for the Management of Mood Disorders. (2013). Amerika Serikat: Cambridge University Press."While both mania and hypomania are phenomenologically similar in that they occur as discrete episodes ... "

- ^ admin. "PMS". Women's International Pharmacy. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

In PMS: Solving the Puzzle, Linaya Hahn identifies five patterns of symptoms, occurring primarily within the luteal phase but varying in timing and intensity (see Patterns of PMS Symptoms)

- ^ Bowen, Rudy; Bowen, Angela; Baetz, Marilyn; Wagner, Jason; Pierson, Roger (2011). "Mood Instability in Women With Premenstrual Syndrome". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 33 (9): 927–934. doi:10.1016/s1701-2163(16)35018-6. ISSN 1701-2163. PMID 21923990.

(graph PMS pattern)...Key characteristics of PMS include a lack of symptoms during the follicular phase, a peak of symptoms during the late luteal or premenstrual phase, and a sudden decrease of symptoms with the onset of menses.

- ^ Dilbaz, Berna; Aksan, Alperen (28 May 2021). "Premenstrual syndrome, a common but underrated entity: review of the clinical literature". Journal of the Turkish German Gynecological Association. 22 (2): 139–148. doi:10.4274/jtgga.galenos.2021.2020.0133. ISSN 1309-0399. PMC 8187976. PMID 33663193.

The ACOG definition involves the presence of at least one of the six affective symptoms (angry outbursts, depression, anxiety, confusion, irritability and social withdrawal) and one of the four somatic…

- ^ Southward, Matt & Semcho, Stephen & Stumpp, Nicole & MacLean, Destiney & Sauer, Shannon. (2020). A Day in the Life of Borderline Personality Disorder: A Preliminary Analysis of Within-Day Emotion Generation and Regulation. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 42. 702-713. 10.1007/s10862-020-09836-1."Graph"

- ^ Carpenter, Ryan W.; Trull, Timothy J. (2013). "Components of emotion dysregulation in borderline personality disorder: a review". Current Psychiatry Reports. 15 (1): 335. doi:10.1007/s11920-012-0335-2. ISSN 1535-1645. PMC 3973423. PMID 23250816.

It consists of a heightened emotional reactivity to environmental stimuli, including emotions of others. Emotion sensitivity in BPD has primarily been associated with negative mood states (e.g., anger, fear, sadness) and not positive emotions (although see [9, 10]).

- ^ Paris, Joel (7 June 2005). "Borderline personality disorder". CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 172 (12): 1579–1583. doi:10.1503/cmaj.045281. ISSN 1488-2329. PMC 558173. PMID 15939918.

...but in BPD, symptoms are usually associated with mood instability rather than with the extended and continuous periods of lower mood seen in classic mood disorders.19 Also, because of characteristic mood swings, BPD is often mistaken for bipolar disorder.30 However, patients with BPD do not show continuously elevated mood but instead exhibit a pattern of rapid shifts in affect related to environmental events, with "high" periods that last for hours rather than for days or weeks.

- ^ Bertsch, Katja; Back, Sarah; Flechsenhar, Aleya; Neukel, Corinne; Krauch, Marlene; Spieß, Karen; Panizza, Angelika; Herpertz, Sabine C. (2021). "Don't Make Me Angry: Frustration-Induced Anger and Its Link to Aggression in Women With Borderline Personality Disorder". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 12 695062. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.695062. ISSN 1664-0640. PMC 8195331. PMID 34122197.

Individuals with BPD report more negative emotions and a greater intensity of negative emotions than healthy individuals throughout the day (9). However, recent data suggest a particular relevance of anger, a negative emotion that is closely related to reactive aggression, in BPD. Using e-diaries, Kockler et al. (10) found that individuals with BPD exhibit anger more frequently in their daily life than healthy as well as clinical control groups and feelings of anger accounted for more distress than pure emotional intensity.

- ^ Reich Brad. (2012).Affective Instability in Borderline Personality Disorder.McLean Hospital."Graph"

- ^ Koenigsberg, Harold W.; Harvey, Philip D.; Mitropoulou, Vivian; Schmeidler, James; New, Antonia S.; Goodman, Marianne; Silverman, Jeremy M.; Serby, Michael; Schopick, Frances; Siever, Larry J. (2002). "Characterizing Affective Instability in Borderline Personality Disorder". American Journal of Psychiatry. 159 (5): 784–788. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.784. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 11986132.

The results of this study suggest that the presence of greater lability in terms of anger, anxiety, and depression/anxiety oscillation characterizes borderline personality disorder, while suggesting that the subjective sense of high affective intensity is present in this population but does not explain these other affective phenomena.

- ^ Beatson, Josephine A.; Rao, Sathya (29 October 2013). "Depression and borderline personality disorder". Medical Journal of Australia. 199 (6): S24-7. doi:10.5694/mja12.10474. ISSN 0025-729X. PMID 25370280. S2CID 22836499.

Depressive symptoms that occur as part of BPD are usually transient and related to interpersonal stress (eg, after an event arousing feelings of rejection). Such "depression" usually lifts dramatically when the relationship is restored. Depressive symptoms in BPD may also serve to express feelings (eg, anger, frustration, hatred, helplessness, powerlessness, disappointment) that the patient is not able to express in more adaptive ways.

- ^ Köhling, Johanna; Ehrenthal, Johannes C.; Levy, Kenneth N.; Schauenburg, Henning; Dinger, Ulrike (1 April 2015). "Quality and severity of depression in borderline personality disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Clinical Psychology Review. 37: 13–25. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.002. ISSN 0272-7358. PMID 25723972.

Moderator analyses revealed lower depression severity in BPD patients without comorbid DeDs, but higher severity in BPD patients with comorbid DeDs compared to depressed controls...some authors labeled the depression experienced in BPD "borderline-depression", characterized by distinct feelings of loneliness and isolation (Adler and Buie, 1979, Grinker et al., 1968), emptiness or boredom (Gunderson, 1996), high dependency and fears of abandonment (Masterson, 1976), as well as intense anger and hate toward the self and others (Hartocollis, 1977, Kernberg, 1975, Kernberg, 1992).

- ^ a b FW, Reimherr & Marchant, Barrie & Olsen, John & C, Halls & Kondo, Douglas & ED, Lyon & Robison, Reid. (2010). Emotional dysregulation as a core feature of adult ADHD: Its relationship with clinical variables and treatment response in two methylphenidate trials. Journal of ADHD and Related Disorders. 1. 53-64. "Graph"

- ^ Skirrow, Caroline; Asherson, Philip (1 May 2013). "Emotional lability, comorbidity and impairment in adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder". Journal of Affective Disorders. 147 (1): 80–86. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.011. ISSN 0165-0327. PMID 23218897.

This study replicates research showing that adults with ADHD report heighted emotional lability (EL), which contributes to impairments in their daily life.

- ^ J. Rosen, Paul; N. Epstein, Jeffery (2010). "A pilot study of ecological momentary assessment of emotion dysregulation in children" (PDF). Journal of ADHD & Related Disorder. 1 (4): 49 – via semantic scholar.

This pattern is consistent with the pattern of dysregulation demonstrated by the ADHD-EDr child in the present study, as he demonstrated generally low positive affect along with 10 single time-point ratings of mild to moderate irritability over the 4 weeks.

- ^ Winstanley, Catharine A.; Eagle, Dawn M.; Robbins, Trevor W. (2006). "Behavioral models of impulsivity in relation to ADHD: translation between clinical and preclinical studies". Clinical Psychology Review. 26 (4): 379–395. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.001. ISSN 0272-7358. PMC 1892795. PMID 16504359.

However, common themes include decreased inhibitory control, intolerance of delay to rewards and quick decision-making due to lack of consideration, as well as more universal deficits such as poor attentional ability.

- ^ Ciompi, Luc (2015). "The key role of emotions in the schizophrenia puzzle". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 41 (2): 318–322. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbu158. ISSN 1745-1701. PMC 4332953. PMID 25481397.

Kraepelin1 and Bleuler2 had already mainly focused on "flat" or "inappropriate" emotions as core features of the illness.

- ^ Høegh, Margrethe Collier; Melle, Ingrid; Aminoff, Sofie R.; Haatveit, Beathe; Olsen, Stine Holmstul; Huflåtten, Idun B.; Ueland, Torill; Lagerberg, Trine Vik (2021). "Characterization of affective lability across subgroups of psychosis spectrum disorders". International Journal of Bipolar Disorders. 9 (1): 34. doi:10.1186/s40345-021-00238-0. ISSN 2194-7511. PMC 8566621. PMID 34734342.

There were no statistically significant differences between individuals with BD-I and SZ for any ALS-SF dimension and these two groups had very similar score patterns throughout. This suggests that despite the overlap in core affective symptom profiles of BD-I and BD-II, the BD-I group is more similar to SZ than it is to BD-II concerning levels of affective lability.

- ^ van Rossum, Inge; Dominguez, Maria-de-Gracia; Lieb, Roselind; Wittchen, Hans-Ulrich; van Os, Jim (2011). "Affective dysregulation and reality distortion: a 10-year prospective study of their association and clinical relevance". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 37 (3): 561–571. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp101. ISSN 1745-1701. PMC 3080695. PMID 19793794.

Evidence from multiple domains indicates that affective dysregulation is strongly associated with reality distortion.1,2 Genetic epidemiological studies have demonstrated that the liabilities for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia are correlated.

- ^ Kilian, Sanja; Asmal, Laila; Goosen, Anneke; Chiliza, Bonginkosi; Phahladira, Lebogang; Emsley, Robin (2015). "Instruments measuring blunted affect in schizophrenia: a systematic review". PLOS ONE. 10 (6) e0127740. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1027740K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127740. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4452733. PMID 26035179.

Blunted affect, also referred to as emotional blunting, is a prominent symptom of schizophrenia. Patients with blunted affect have difficulty in expressing their emotions [1], characterized by diminished facial expression, expressive gestures and vocal expressions in reaction to emotion provoking stimuli [1–3]. However, patients' reduced outward emotional expression may not mirror subjective internal emotional experiences [4] suggesting a disconnect in what patients experience, perceive and express when interpreting emotional stimuli [5] due to problems associated with emotional processing [6–7].

- ^ Docherty, Nancy M.; St-Hilaire, Annie; Aakre, Jennifer M.; Seghers, James P. (2009). "Life events and high-trait reactivity together predict psychotic symptom increases in schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 35 (3): 638–645. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn002. ISSN 0586-7614. PMC 2669571. PMID 18245057.

There is evidence that the occurrence of stressful life events3,6–8 or the presence of social relationship stressors such as high levels of familial "expressed emotion9–11" are associated with subsequent exacerbation of psychotic symptoms in patients as a group.

- ^ Thompson, Renee J.; Mata, Jutta; Jaeggi, Susanne M.; Buschkuehl, Martin; Jonides, John; Gotlib, Ian H. (2012). "The everyday emotional experience of adults with major depressive disorder: Examining emotional instability, inertia, and reactivity". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 121 (4): 819–829. doi:10.1037/a0027978. ISSN 1939-1846. PMC 3624976. PMID 22708886.

Whether depressed individuals and healthy controls will differ in their instability of PA is less clear. As we noted above, depressed individuals have been found to have blunted emotional responses to valenced stimuli in the laboratory (Bylsma, et al., 2008) and decreased responsivity to reward (e.g., Pizzagalli, Iosifescu, Hallett, Ratner, & Fava, 2009)...

- ^ Bowen, Rudy; Peters, Evyn; Marwaha, Steven; Baetz, Marilyn; Balbuena, Lloyd (2017). "Moods in Clinical Depression Are More Unstable than Severe Normal Sadness". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 8: 56. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00056. ISSN 1664-0640. PMC 5388683. PMID 28446884.

He noted that people with melancholia could become over-talkative and manic but did not adequately explain why this is so." & "On the VAS ratings, the depressed group experienced more severe low moods and less severe high moods than the non-depressed group, as would be expected given the selection criteria. This is consistent with reports of more severe negative emotions and variable positive emotions in ecological momentary assessment studies of patients with major depression (12, 33, 53).

- ^ Christensen, Michael Cronquist; Ren, Hongye; Fagiolini, Andrea (4 April 2022). "Emotional blunting in patients with depression. Part I: clinical characteristics". Annals of General Psychiatry. 21 (1): 10. doi:10.1186/s12991-022-00387-1. ISSN 1744-859X. PMC 8981644. PMID 35379283.

Emotional effects of depression and treatment vary, but may include, for example, feeling emotionally "numbed" or "blunted" in some way; lacking positive emotions or negative emotions; feeling detached from the world around you...

- ^ Sperry, Sarah Havens; Walsh, Molly A.; Kwapil, Thomas Richard (30 September 2019). "Emotion Dynamics Concurrently and Prospectively Predict Mood Psychopathology". Journal of Affective Disorders. 261: 67–75. doi:10.31234/osf.io/n7xza. PMID 31600589. S2CID 242802425.

Major depressive disorder is characterized by high mean NA and low mean PA (e.g., Watson et al., 1988).... Note that major depressive disorder generally is unassociated with instability of NA or PA (Köhling et al., 2016; Koval et al., 2013).

- ^ Murray, Greg (1 September 2007). "Diurnal mood variation in depression: A signal of disturbed circadian function?". Journal of Affective Disorders. Depression and Anxiety in Women across Cultures. 102 (1): 47–53. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.12.001. ISSN 0165-0327. PMID 17239958.

Diurnal variation in mood is a prominent symptom of depression, and is typically experienced as positive mood variation (PMV — mood being worse upon waking and better in the evening).

- ^ Loas, Gwenolé; Salinas, Eliseo; Pierson, Annick; Guelfi, Julien D.; Samuel-Lajeunesse, Bertrand (1 September 1994). "Anhedonia and blunted affect in major depressive disorder". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 35 (5): 366–372. doi:10.1016/0010-440X(94)90277-1. ISSN 0010-440X. PMID 7995029.

The depressives are more sensitive to displeasure and more anhedonic than controls.

- ^ Faedda, Gianni L.; Marangoni, Ciro; Reginaldi, Daniela (1 May 2015). "Depressive mixed states: A reappraisal of Koukopoulos׳criteria". Journal of Affective Disorders. 176: 18–23. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.053. ISSN 0165-0327. PMID 25687279.

The mixed depressive syndrome is not a transitory state but a state of long duration, which may last weeks or several months. The clinical picture is characterized by dysphoric mood, emotional lability, psychic and/or motor agitation, talkativeness, crowded and/or racing thoughts, rumination, initial or middle insomnia.

- ^ Wonderlich, Stephen A.; Rosenfeldt, Steven; Crosby, Ross D.; Mitchell, James E.; Engel, Scott G.; Smyth, Joshua; Miltenberger, Raymond (2007). "The effects of childhood trauma on daily mood lability and comorbid psychopathology in bulimia nervosa". Journal of Traumatic Stress. 20 (1): 77–87. doi:10.1002/jts.20184. PMID 17345648.

Emotional abuse was associated with average daily mood and mood lability.

- ^ Power, Mick J.; Fyvie, Claire (2013). "The Role of Emotion in PTSD: Two Preliminary Studies". Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 41 (2): 162–172. doi:10.1017/S1352465812000148. ISSN 1352-4658. PMID 22452905. S2CID 33989429.

The results showed that less than 50% of PTSD cases presented with anxiety as the primary emotion, with the remainder showing primary emotions of sadness, anger, or disgust rather than anxiety

- ^ Price, Matthew; Legrand, Alison C.; Brier, Zoe M. F.; Gratton, Jennifer; Skalka, Christian (2020). "The short-term dynamics of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms during the acute posttrauma period". Depression and Anxiety. 37 (4): 313–320. doi:10.1002/da.22976. ISSN 1520-6394. PMC 8340953. PMID 31730736.

Taken together, these results indicate that PTSD development is a dynamic process in which symptoms interact over time (Gelkopf et al., 2017). As hypothesized, intrusions and AAR symptoms may be more important early on and lead to other symptoms in the disorder.

- ^ Shalev, Arieh Y. (2009). "Posttraumatic stress disorder and stress-related disorders". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 32 (3): 687–704. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.001. ISSN 1558-3147. PMC 2746940. PMID 19716997.

Chronic PTSD most often co-occurs with mood, anxiety and substance use disorders. It is highly reactive to environmental reminders of the traumatic event and to renewed life-stressors, and thus may have a fluctuating course (23).

- ^ Newton, Tamara; Ho, Ivy (4 December 2008). "Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms and Emotion Experience in Women: Emotion Occurrence, Intensity, and Variability in the Natural Environment". Journal of Psychological Trauma. 7 (4): 276–297. doi:10.1080/19322880802492237. ISSN 1932-2887. S2CID 144129832.

Posttraumatic stress symptom severity was uniquely correlated with greater intensity and variability, but not occurrence, of certain negative emotions, and with less frequent occurrence but greater variability of joy/happiness. Intrusive reexperiencing was uniquely associated with greater variability of both anxiety and joy/happiness. Results suggest that women with more severe posttraumatic stress symptoms do not experience more episodes of negative emotion but, once emotion occurs, they have difficulty modulating its intensity.

- ^ Yehuda, Rachel; LeDoux, Joseph (4 October 2007). "Response Variation following Trauma: A Translational Neuroscience Approach to Understanding PTSD". Neuron. 56 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.006. ISSN 0896-6273. PMID 17920012. S2CID 25239428.

Reexperiencing symptoms describe spontaneous, often insuppressible intrusions of the traumatic memory in the form of images or nightmares that are accompanied by intense physiological distress...Hyperarousal symptoms reflect more overt physiological manifestations, such as insomnia, irritability, impaired concentration, hypervigilance, and increased startle responses.

- ^ Schoenleber, Michelle; Berghoff, Christopher R.; Gratz, Kim L.; Tull, Matthew T. (2018). "Emotional lability and affective synchrony in posttraumatic stress disorder pathology". Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 53: 68–75. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.11.006. ISSN 1873-7897. PMC 5748357. PMID 29197703.

Kleim, Graham, Bryant, and Ehlers (2013) asked a sample of trauma-exposed individuals to report state levels of various unpleasant emotions (i.e., fear, helplessness, anger, guilt, and shame) following naturally occurring intrusive memories over the course of a week.

- ^ "Bipolar Mood Swings, Stabilizers, Triggers, and Mania." WebMD. WebMD, 3 May 0000. Web. 29 February 2012.

- ^ a b "epilepsymatters.com – Home of the Canadian Epilepsy Alliance". Epilepsymatters.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ "Autism spectrum disorder". Nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ "Chat for Adults with HFA and Aspergers: Mood Swings in Adults on the Autism Spectrum". Adultaspergerschat.com. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ Donna Williams. "Donna Williams: Autism, Puberty and Possibility of Seizures". Donnawilliams.net. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ Stern RA (1996). "Assessment of Mood States in Neurodegenerative Disease: Methodological Issues and Diagnostic Recommendations". Seminars in Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 1 (4): 315–324. doi:10.1053/SCNP00100315 (inactive 10 July 2025). PMID 10320434.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ "Definition & Facts for Celiac Disease. What are the complications of celiac disease?". NIDDK. June 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ Angela Haupt. "Food and Mood: 6 Ways Your Diet Affects How You Feel". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ "Can food affect your mood? – CNN.com". CNN. 26 November 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ "Neurobiology of Mood Disorders." (PDF). Turner-white.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ [1] Archived 4 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hagihara, Hideo; Horikawa, Tomoyasu; Irino, Yasuhiro; Nakamura, Hironori K.; Umemori, Juzoh; Shoji, Hirotaka; Yoshida, Masaru; Kamitani, Yukiyasu; Miyakawa, Tsuyoshi (December 2019). "Peripheral blood metabolome predicts mood change-related activity in mouse model of bipolar disorder". Molecular Brain. 12 (1): 107. doi:10.1186/s13041-019-0527-3. ISSN 1756-6606. PMC 6902552. PMID 31822292.

- ^ Özgürdal, Seza; van Haren, Elisabeth; Hauser, Marta; Ströhle, Andreas; Bauer, Michael; Assion, Hans-Jörg; Juckel, Georg (2009). "Early Mood Swings as Symptoms of the Bipolar Prodrome: Preliminary Results of a Retrospective Analysis". Psychopathology. 42 (5): 337–342. doi:10.1159/000232977. ISSN 0254-4962. PMID 19672137. S2CID 15290117.

- ^ Brickman, H.M.; Young, A.S.; Fristad, M.A. (2023). "Bipolar and related disorders". Encyclopedia of Mental Health. Elsevier. pp. 232–239. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-91497-0.00195-8. ISBN 978-0-323-91498-7.

- ^ Ching, Christopher R. K.; Hibar, Derrek P.; Gurholt, Tiril P.; Nunes, Abraham; Thomopoulos, Sophia I.; Abé, Christoph; Agartz, Ingrid; Brouwer, Rachel M.; Cannon, Dara M.; de Zwarte, Sonja M. C.; Eyler, Lisa T.; Favre, Pauline; Hajek, Tomas; Haukvik, Unn K.; Houenou, Josselin (2022). "What we learn about bipolar disorder from large-scale neuroimaging: Findings and future directions from the ENIGMA Bipolar Disorder Working Group". Human Brain Mapping. 43 (1): 56–82. doi:10.1002/hbm.25098. ISSN 1097-0193. PMC 8675426. PMID 32725849.

Findings and future directions from the ENIGMA Bipolar Disorder Working Group. Hum Brain Mapp. 2022 Jan;43(1):56-82."Initial BD Working Group studies reveal widespread patterns of lower cortical thickness, subcortical volume and disrupted white matter integrity associated with BD. Findings also include mapping brain alterations of

- ^ Jain, Ankit; Mitra, Paroma (2023). "Bipolar Disorder". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32644424. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

Currently, the etiology of BD is unknown but appears to be due to an interaction of genetic, epigenetic, neurochemical, and environmental factors. Heritability is well established.[3][4][5] Numerous genetic loci have been implicated as increasing the risk of BD; the first was noted in 1987 with "DNA markers" on the short arm of chromosome 11. Since then, an association has been made between at least 30 genes and an increased risk of the condition.[6]

- ^ Benoit, M.; Robert, P.H. (2003). "Behavior, Neural Basis of". Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences. Elsevier. pp. 364–369. doi:10.1016/b0-12-226870-9/00418-4. ISBN 978-0-12-226870-0.

mesial limbic system (nucleus accumbens, amygdala, and hippocampus) and the entire prefrontal cortex. They play a determining role in emotional expression and motivation. For example, a reduction in the activity of the mesocortical pathway will result in a paucity of affect and loss of motivation and planning

- ^ Su, Tung-Ping (2 June 1993). "Neuropsychiatric Effects of Anabolic Steroids in Male Normal Volunteers". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 269 (21): 2760–2764. doi:10.1001/jama.1993.03500210060032. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 8492402.

- ^ Lenko, Iil; Mäenpää, J.; Mäkitie, O.; Perheentupa, J. (1988). "Low Dose Testosterone Treatment of Delayed Growth". Pediatric Research. 23 (1): 124. doi:10.1203/00006450-198801000-00139. ISSN 1530-0447. S2CID 6016824.

Anabolic steroids are used to accelerate the growth of normal boys with constitutional, delay of growth and puberty

- ^ Mottram, David R.; George, Alan J. (1 March 2000). "Anabolic steroids". Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 14 (1): 55–69. doi:10.1053/beem.2000.0053. ISSN 1521-690X. PMID 10932810.

The anabolic effects are considered to be those promoting protein synthesis, muscle growth and crythopoiesis

- ^ Newshan, Gayle; Leon, Wade (1 March 2001). "The use of anabolic agents in HIV disease". International Journal of STD & AIDS. 12 (3): 141–144. doi:10.1258/0956462011916893. ISSN 0956-4624. PMID 11231865. S2CID 6055905.

Anabolic steroids and other agents are fast becoming part of the standard of care for HIV disease, gaining acceptance in reversing loss of lean body mass...

- ^ Piacentino, Daria; Kotzalidis, Georgios D.; Del Casale, Antonio; Aromatario, Maria Rosaria; Pomara, Cristoforo; Girardi, Paolo; Sani, Gabriele (2015). "Anabolic-androgenic steroid use and psychopathology in athletes. A systematic review". Current Neuropharmacology. 13 (1): 101–121. doi:10.2174/1570159X13666141210222725. ISSN 1570-159X. PMC 4462035. PMID 26074746.

High doses of AASs can lead to serious physical and psychological complications, such as hypertension, atherosclerosis, myocardial hypertrophy and infarction, abnormal blood clotting, hepatotoxicity and hepatic tumors, tendon damage, reduced libido, and psychiatric/behavioral symptoms like aggressiveness and irritability

- ^ Hauger, Lisa E.; Westlye, Lars T.; Fjell, Anders M.; Walhovd, Kristine B.; Bjørnebekk, Astrid (2019). "Structural brain characteristics of anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence in men". Addiction. 114 (8): 1405–1415. doi:10.1111/add.14629. ISSN 1360-0443. PMC 6767448. PMID 30955206.

AAS users who fulfilled the criteria for AAS‐dependence had significantly thinner cortex in frontal, temporal, parietal, occipital and pre‐frontal regions compared to non‐dependent users

- ^ SANTOS, JOÃO PEDRO BELCHIOR; LACERDA, FRANCIELLY BAÊTA; OLIVEIRA, LEANDRO ALMEIDA DE; FIALHO, BRENDA BORCARD; ASSUNÇÃO, ISADORA NOGUEIRA; SANTANA, MARCOS GONÇALVES; GOMIDES, LINDISLEY FERREIRA; CUPERTINO, MARLI DO CARMO (2020). "NEUROLOGICAL CONSEQUENCES OF ABUSIVE USE OF ANABOLIC-ANDROGENIC STEROIDS" (PDF). Brazilian Journal of Surgery and Clinical Research. 32 (2): 52–58. eISSN 2317-4404 – via BJSCR.

As a result, it was observed that at NS, these stimulants actuate through a complex signaling systems that include the neuroendocrine alteration of the hypothalamic pituitary-gonadal axis, modification of neurotransmitters and their receptors, as well as the induction of neuronal death by apoptosis in several pathways

- ^ Koutsoklenis, Athanasios; Honkasilta, Juho (10 January 2023). "ADHD in the DSM-5-TR: What has changed and what has not". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 13 1064141. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1064141. ISSN 1664-0640. PMC 9871920. PMID 36704731.

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder defined by impairing levels of inattention, disorganization, and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity. Inattention and disorganization entail inability to stay on task, seeming not to listen, and losing materials necessary for tasks, at levels that are inconsistent with age or developmental level.

- ^ Ashinoff, Brandon K.; Abu-Akel, Ahmad (1 February 2021). "Hyperfocus: the forgotten frontier of attention". Psychological Research. 85 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1007/s00426-019-01245-8. ISSN 1430-2772. PMC 7851038. PMID 31541305.

Ozel-Kizil et al. (2013; also see Ozel-Kizil et al., 2014) defined hyperfocusing as being "characterized by intensive concentration on interesting and non-routine activities accompanied by temporarily diminished perception of the environment".

- ^ "Can ADHD Cause Mood Swings?". Psych Central. 12 August 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

ADHD-induced mood shifts may be a result of being distracted, comorbid conditions like depression or bipolar disorder, or a side effect of certain medications.

- ^ McDonagh, Tracey; Travers, Áine; Bramham, Jessica (3 July 2019). "Do Neuropsychological Deficits Predict Anger Dysregulation in Adults with ADHD?". International Journal of Forensic Mental Health. 18 (3): 200–211. doi:10.1080/14999013.2018.1508095. ISSN 1499-9013. S2CID 149490018.

Shifting attention was more significantly associated with trait anger and anger out than response inhibition, which was significantly related to anger control

- ^ Arnsten, Amy F.T. (2009). "ADHD and the Prefrontal Cortex". The Journal of Pediatrics. 154 (5): I–S43. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.018. PMC 2894421. PMID 20596295.

Studies have found that ADHD is associated with weaker function and structure of prefrontal cortex (PFC) circuits, especially in the right hemisphere.

- ^ Itami, Shouichi; Uno, Hiroyuki (20 December 2002). "Orbitofrontal cortex dysfunction in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder revealed by reversal and extinction tasks". NeuroReport. 13 (18): 2453–2457. doi:10.1097/00001756-200212200-00016. ISSN 0959-4965. PMID 12499848. S2CID 23189353.

ADHD subjects indeed showed a performance deficit in the tasks, supporting OFC dysfunction in ADHD. Furthermore, a discriminat analysis using the task performance variables correctly classified 89.7% of the participants among ADHD patients and normal controls.

- ^ Perlov, Evgeniy; Philipsen, Alexandra; Tebartz van Elst, Ludger; Ebert, Dieter; Henning, Juergen; Maier, Simon; Bubl, Emanuel; Hesslinger, Bernd (2008). "Hippocampus and amygdala morphology in adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 33 (6): 509–515. doi:10.1139/jpn.0848. ISSN 1488-2434. PMC 2575764. PMID 18982173.

We conclude that the findings of interest (i.e., hippocampus enlargement and amygdala volume loss) are not very stable across different samples of patients with ADHD and that the different and contradictory findings may be related to the different locations of alterations along the complex circuits responsible for the different symptoms of ADHD.

- ^ Arnsten, Amy P.T. (1 May 2009). "The Emerging Neurobiology of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: The Key Role of the Prefrontal Association Cortex". Journal of Pediatrics. 154 (5): I–S43. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.018. PMC 2894421. PMID 20596295.

The prefrontal association cortex plays a crucial role in regulating attention, behavior, and emotion, with the right hemisphere specialized for behavioral inhibition.

- ^ Hodges, Holly; Fealko, Casey; Soares, Neelkamal (2020). "Autism spectrum disorder: definition, epidemiology, causes, and clinical evaluation". Translational Pediatrics. 9 (S1): S55 – S65. doi:10.21037/tp.2019.09.09. ISSN 2224-4336. PMC 7082249. PMID 32206584.

Table 1 :Changes in ASD criteria from the DSM-IV to DSM-5

- ^ MacLennan, K.; O'Brien, S.; Tavassoli, T. (2022). "In Our Own Words: The Complex Sensory Experiences of Autistic Adults". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 52 (7): 3061–3075. doi:10.1007/s10803-021-05186-3. ISSN 0162-3257. PMC 9213348. PMID 34255236.

Difficulties with sensory input was described to impact mood, causing stress and agitation:

- ^ Green, Shulamite A.; Hernandez, Leanna; Tottenham, Nim; Krasileva, Kate; Bookheimer, Susan Y.; Dapretto, Mirella (2015). "Neurobiology of Sensory Overresponsivity in Youth With Autism Spectrum Disorders". JAMA Psychiatry. 72 (8): 778–786. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0737. ISSN 2168-6238. PMC 4861140. PMID 26061819.

The authors found that youth with ASDs had overactivation in limbic areas, primary sensory cortices, and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) compared with typically developing (TD) control subjects in response to mildly aversive visual and auditory stimuli." & "Finally, Green et al10 found that SOR symptoms correlated with hyperactivity in the amygdala and OFC.

- ^ Ibrahim, Karim; Eilbott, Jeffrey A.; Ventola, Pamela; He, George; Pelphrey, Kevin A.; McCarthy, Gregory; Sukhodolsky, Denis G. (2019). "Reduced Amygdala–Prefrontal Functional Connectivity in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder and Co-occurring Disruptive Behavior". Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging. 4 (12): 1031–1041. doi:10.1016/j.bpsc.2019.01.009. ISSN 2451-9022. PMC 7173634. PMID 30979647.

Children with ASD and disruptive behavior showed reduced amygdala–vlPFC connectivity compared with children with ASD without disruptive behavior.

- ^ Fonagy, Peter; Luyten, Patrick; Allison, Elizabeth; Campbell, Chloe (2017). "What we have changed our minds about: Part 1. Borderline personality disorder as a limitation of resilience". Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation. 4 (1): 11. doi:10.1186/s40479-017-0061-9. ISSN 2051-6673. PMC 5389119. PMID 28413687.

In BPD, the appraisal mechanisms are at fault, in large part because of mentalizing difficulties (e.g. in the mistaken appraisal of threat at the moment of its presentation) or a breakdown in epistemic trust, which damages the capacity to relearn different ways of mentalizing – or appraising – situations (i.e. the inability to change our understanding of the threat after the event).

- ^ Chapman, Jennifer; Jamil, Radia T.; Fleisher, Carl (25 October 2022), "Borderline Personality Disorder", StatPearls [Internet], StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28613633, retrieved 7 August 2023,

There are many theories about the development of borderline personality disorder. In the mentalizing model of Peter Fonagy and Anthony Bateman, borderline personality disorder is the result of a lack of resilience against psychological stressors. In this framework, Fonagy and Bateman define resilience as the ability to generate adaptive re-appraisal of negative events or stressors;...

- ^ Lazarus, Sophie A.; Choukas-Bradley, Sophia; Beeney, Joseph E.; Byrd, Amy L.; Vine, Vera; Stepp, Stephanie D. (2019). "Too Much Too Soon?: Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms and Romantic Relationships in Adolescent Girls". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 47 (12): 1995–2005. doi:10.1007/s10802-019-00570-1. ISSN 1573-2835. PMC 7045362. PMID 31240430.

Core symptoms that comprise the disorder are often explicitly interpersonal in nature (e.g., tumultuous romantic relationships and frantic efforts to avoid abandonment) or are expressed in reaction to interpersonal stressors (e.g., affective instability, paranoid ideation, suicidal behavior

- ^ Nicol, Katie; Pope, Merrick; Sprengelmeyer, Reiner; Young, Andrew W.; Hall, Jeremy (6 November 2013). "Social Judgement in Borderline Personality Disorder". PLOS ONE. 8 (11) e73440. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...873440N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073440. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3819347. PMID 24223110.

Individuals with a diagnosis of BPD have difficulty making appropriate social judgements about others from their faces. Judging more faces as unapproachable and untrustworthy indicates that this group may have a heightened sensitivity to perceiving potential threat, and this should be considered in clinical management and treatment

- ^ Balsis, Steve; Loehle-Conger, Evan; Busch, Alexander J.; Ungredda, Tatiana; Oltmanns, Thomas F. (2018). "Self and informant report across the borderline personality disorder spectrum". Personality Disorders. 9 (5): 429–436. doi:10.1037/per0000259. ISSN 1949-2723. PMC 6082732. PMID 28857585.

Individuals with BPD features often have distorted cognitions. Specifically, they often make simplified judgments about people and situations.