Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Network interface controller

View on Wikipedia | |

| Connects to | Motherboard via one of:

Network via one of: |

|---|---|

| Speeds |

|

| Common manufacturers | |

A network interface controller (NIC, also known as a network interface card,[3] network adapter, LAN adapter and physical network interface[4]) is a computer hardware component that connects a computer to a computer network.[5]

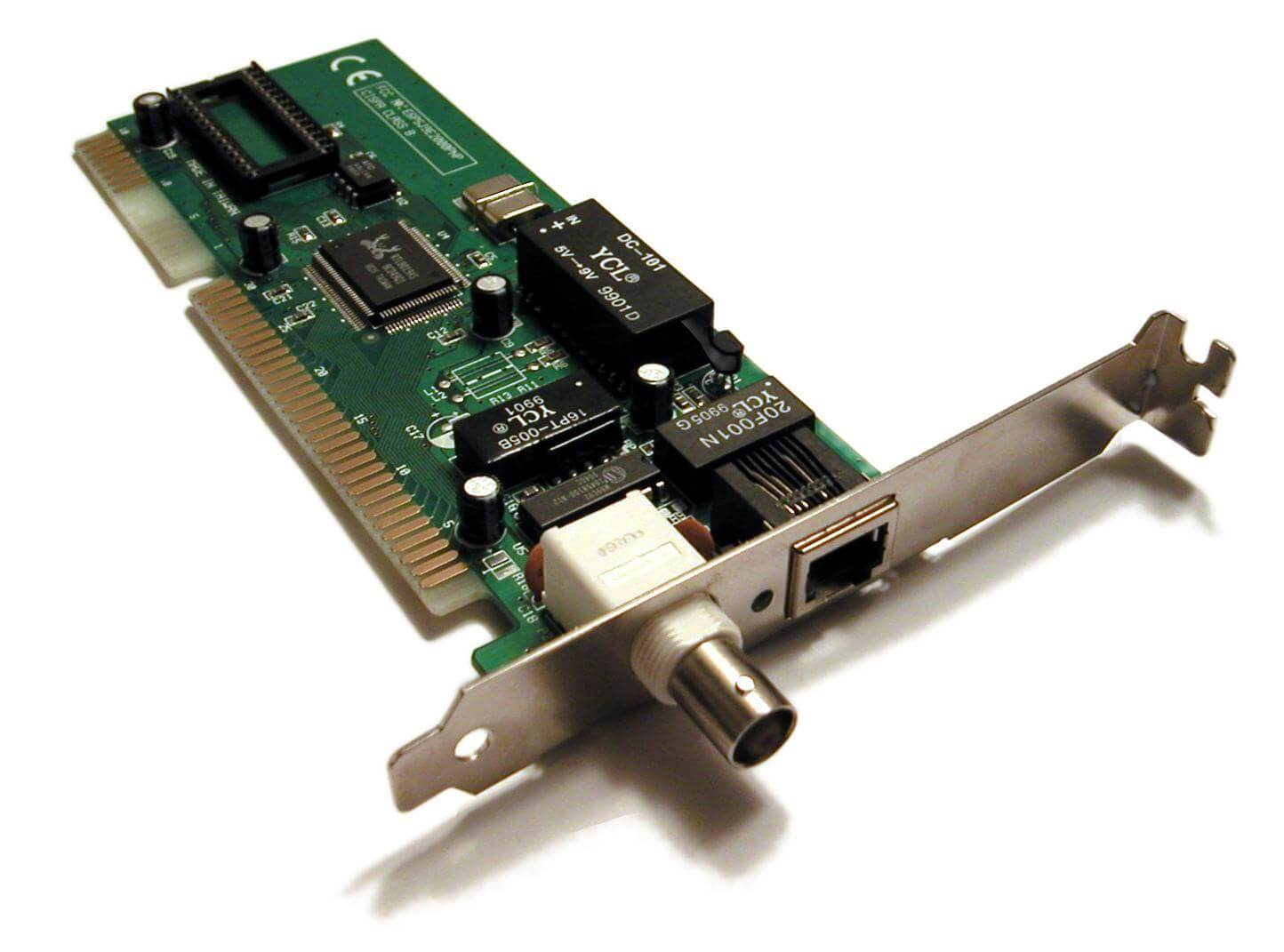

Early network interface controllers were commonly implemented on expansion cards that plugged into a computer bus. The low cost and ubiquity of the Ethernet standard means that most newer computers have a network interface built into the motherboard, or is contained into a USB-connected dongle, although network cards remain available.

Modern network interface controllers offer advanced features such as interrupt and DMA interfaces to the host processors, support for multiple receive and transmit queues, partitioning into multiple logical interfaces, and on-controller network traffic processing such as the TCP offload engine.

Purpose

[edit]The network controller implements the electronic circuitry required to communicate using a specific physical layer and data link layer standard such as Ethernet or Wi-Fi.[a] This provides a base for a full network protocol stack, allowing communication among computers on the same local area network (LAN) and large-scale network communications through routable protocols, such as Internet Protocol (IP).

The NIC allows computers to communicate over a computer network, either by using cables or wirelessly. The NIC is both a physical layer and data link layer device, as it provides physical access to a networking medium and, for IEEE 802 and similar networks, provides a low-level addressing system through the use of MAC addresses that are uniquely assigned to network interfaces.

Implementation

[edit]

Network controllers were originally implemented as expansion cards that plugged into a computer bus. The low cost and ubiquity of the Ethernet standard means that most new computers have a network interface controller built into the motherboard. Newer server motherboards may have multiple network interfaces built-in. The Ethernet capabilities are either integrated into the motherboard chipset or implemented via a low-cost dedicated Ethernet chip. A separate network card is typically no longer required unless additional independent network connections are needed or some non-Ethernet type of network is used. A general trend in computer hardware is towards integrating the various components of systems on a chip, and this is also applied to network interface cards.

An Ethernet network controller typically has an 8P8C socket where the network cable is connected. Older NICs also supplied BNC, or AUI connections. Ethernet network controllers typically support 10 Mbit/s Ethernet, 100 Mbit/s Ethernet, and 1000 Mbit/s Ethernet varieties. Such controllers are designated as 10/100/1000, meaning that they can support data rates of 10, 100 or 1000 Mbit/s. 10 Gigabit Ethernet NICs are also available, and, as of November 2014[update], are beginning to be available on computer motherboards.[6][7]

Modular designs like SFP and SFP+ are highly popular, especially for fiber-optic communication. These define a standard receptacle for media-dependent transceivers, so users can easily adapt the network interface to their needs.

LEDs adjacent to or integrated into the network connector inform the user of whether the network is connected, and when data activity occurs.

The NIC may include ROM to store its factory-assigned MAC address.[8]

The NIC may use one or more of the following techniques to indicate the availability of packets to transfer:

- Polling is where the CPU examines the status of the peripheral under program control.

- Interrupt-driven I/O is where the peripheral alerts the CPU that it is ready to transfer data.

NICs may use one or more of the following techniques to transfer packet data:

- Programmed input/output, where the CPU moves the data to or from the NIC to memory.

- Direct memory access (DMA), where a device other than the CPU assumes control of the system bus to move data to or from the NIC to memory. This removes load from the CPU but requires more logic on the card. In addition, a packet buffer on the NIC may not be required and latency can be reduced.

Performance and advanced functionality

[edit]

Multiqueue NICs provide multiple transmit and receive queues, allowing packets received by the NIC to be assigned to one of its receive queues. The NIC may distribute incoming traffic between the receive queues using a hash function. Each receive queue is assigned to a separate interrupt; by routing each of those interrupts to different CPUs or CPU cores, processing of the interrupt requests triggered by the network traffic received by a single NIC can be distributed improving performance.[10][11]

The hardware-based distribution of the interrupts, described above, is referred to as receive-side scaling (RSS).[12]: 82 Purely software implementations also exist, such as the receive packet steering (RPS), receive flow steering (RFS),[10] and Intel Flow Director.[12]: 98, 99 [13][14][15] Further performance improvements can be achieved by routing the interrupt requests to the CPUs or cores executing the applications that are the ultimate destinations for network packets that generated the interrupts. This technique improves locality of reference and results in higher overall performance, reduced latency and better hardware utilization because of the higher utilization of CPU caches and fewer required context switches.

With multi-queue NICs, additional performance improvements can be achieved by distributing outgoing traffic among different transmit queues. By assigning different transmit queues to different CPUs or CPU cores, internal operating system contentions can be avoided. This approach is usually referred to as transmit packet steering (XPS).[10]

Some products feature NIC partitioning (NPAR, also known as port partitioning) that uses SR-IOV virtualization to divide a single 10 Gigabit Ethernet NIC into multiple discrete virtual NICs with dedicated bandwidth, which are presented to the firmware and operating system as separate PCI device functions.[3][16]

Some NICs provide a TCP offload engine to offload processing of the entire TCP/IP stack to the network controller. It is primarily used with high-speed network interfaces, such as Gigabit Ethernet and 10 Gigabit Ethernet, for which the processing overhead of the network stack becomes significant.[17]

Some NICs offer integrated field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) for user-programmable processing of network traffic before it reaches the host computer, allowing for significantly reduced latencies in time-sensitive workloads.[18] Moreover, some NICs offer complete low-latency TCP/IP stacks running on integrated FPGAs in combination with userspace libraries that intercept networking operations usually performed by the operating system kernel; Solarflare's open-source OpenOnload network stack that runs on Linux is an example. This kind of functionality is usually referred to as user-level networking.[19][20][21]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Although other network technologies exist, Ethernet (IEEE 802.3) and Wi-Fi (IEEE 802.11) have achieved near-ubiquity as LAN technologies since the mid-1990s.

References

[edit]- ^ "Port speed and duplex mode configuration". docs.ruckuswireless.com. Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- ^ Admin, Arista (2020-04-23). "Section 11.2: Ethernet Standards - Arista". Arista Networks. Retrieved 2020-09-28.

- ^ a b "Enhancing Scalability Through Network Interface Card Partitioning" (PDF). Dell. April 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ "Physical Network Interface". Microsoft. January 7, 2009.

- ^ Posey, Brien M. (2006). "Networking Basics: Part 1 - Networking Hardware". Windowsnetworking.com. TechGenix Ltd. Retrieved 2012-06-09.

- ^ Jim O'Reilly (2014-01-22). "Will 2014 Be The Year Of 10 Gigabit Ethernet?". Network Computing. Archived from the original on 2015-05-10. Retrieved 2015-04-29.

- ^ "Breaking Speed Limits with ASRock X99 WS-E/10G and Intel 10G BASE-T LANs". asrock.com. 24 November 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ John Savill (Nov 12, 2000). "How can I change a network adapter card's MAC address?". Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ "Intel 82574 Gigabit Ethernet Controller Family Datasheet" (PDF). Intel. June 2014. p. 1. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- ^ a b c Tom Herbert; Willem de Bruijn (May 9, 2014). "Linux kernel documentation: Documentation/networking/scaling.txt". kernel.org. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- ^ "Intel Ethernet Controller i210 Family Product Brief" (PDF). Intel. 2012. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- ^ a b "Intel Look Inside: Intel Ethernet" (PDF). Xeon E5 v3 (Grantley) Launch. Intel. November 27, 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2015. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ "Linux kernel documentation: Documentation/networking/ixgbe.txt". kernel.org. December 15, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ "Intel Ethernet Flow Director". Intel. February 16, 2015. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ "Introduction to Intel Ethernet Flow Director and Memcached Performance" (PDF). Intel. October 14, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- ^ Patrick Kutch; Brian Johnson; Greg Rose (September 2011). "An Introduction to Intel Flexible Port Partitioning Using SR-IOV Technology" (PDF). Intel. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ^ Jonathan Corbet (August 1, 2007). "Large receive offload". LWN.net. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- ^ "High Performance Solutions for Cyber Security". New Wave Design & Verification. New Wave DV.

- ^ Timothy Prickett Morgan (2012-02-08). "Solarflare turns network adapters into servers: When a CPU just isn't fast enough". The Register. Retrieved 2014-05-08.

- ^ "OpenOnload". openonload.org. 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2014-05-08.

- ^ Steve Pope; David Riddoch (2008-03-21). "OpenOnload: A user-level network stack" (PDF). openonload.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-24. Retrieved 2014-05-08.

External links

[edit]Network interface controller

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Role

A network interface controller (NIC), also known as a network interface card or network adapter, is a hardware component that enables a computer or other device to connect to and communicate over a computer network.[8] It serves as the primary interface between the host system and the network medium, handling the exchange of data in the form of packets.[9] The primary roles of a NIC include facilitating the transmission and reception of data packets between the device and the network.[10] It converts digital data from the host into signals suitable for the network medium, such as electrical signals for Ethernet or radio waves for Wi-Fi.[11] Additionally, the NIC provides a Media Access Control (MAC) address, a unique identifier assigned to the hardware for distinguishing the device on the local network segment.[12] NICs operate at the physical and data link layers of the OSI model, implementing the foundational functions for network connectivity.[13] They are essential for both wired networks like Ethernet and wireless networks such as Wi-Fi and Bluetooth, enabling reliable data exchange across diverse media.[14] Examples of NIC implementations include integrated versions embedded directly on a motherboard for standard connectivity in personal computers, and discrete add-in cards that plug into expansion slots for higher performance or specialized needs.[15] These components play a critical role in enabling internet access, local area networking, and interoperability among devices on shared networks.[11] Among common networking devices, the NIC is specifically used for connectivity within a local area network (LAN). It enables a device to connect directly to other devices or network infrastructure on the same LAN, such as via Ethernet to a switch or Wi-Fi to an access point. In contrast, a modem is used to connect a network to a wide area network (WAN), such as an internet service provider's infrastructure for internet access, while a router interconnects multiple networks, including bridging LANs to WANs and directing traffic between them.Historical Development

The origins of the network interface controller (NIC) trace back to the 1970s, coinciding with the development of early packet-switched networks like ARPANET, where host computers required specialized interfaces to connect to Interface Message Processors (IMPs) for data transmission. These rudimentary NICs facilitated the first operational wide-area network connections, enabling resource sharing among research institutions.[16] A pivotal advancement occurred in 1973 when Xerox PARC engineers, led by Robert Metcalfe, developed the Ethernet prototype, a 2.94 Mbps local area network (LAN) using coaxial cable, which laid the groundwork for standardized NIC designs. Metcalfe, who co-invented Ethernet and later formulated Metcalfe's law on network value scaling with connected devices, left Xerox in 1979 to co-found 3Com Corporation. In 1982, 3Com released the first commercial Ethernet NIC, the EtherLink, compatible with Xerox's technology and targeted at personal computers, marking the shift from experimental to market-ready hardware.[17][18][19][20] The 1980s saw diversification with IBM's introduction of Token Ring NICs in 1985, based on the IEEE 802.5 standard, which used a token-passing protocol for deterministic LAN performance in enterprise environments. By the 1990s, Ethernet evolved further; the IEEE 802.3u standard enabled Fast Ethernet at 100 Mbps in 1995, prompting widespread NIC upgrades for higher throughput in office networks. Gigabit Ethernet, standardized by IEEE 802.3z in 1998 and 802.3ab in 1999, saw adoption in the late 1990s and early 2000s, exemplified by Broadcom's BCM5400, the first single-chip Gigabit Ethernet PHY transceiver demonstrated in 1999, which connected to MAC via standard interfaces to enable cost-effective implementations.[21][22][23] Major architectural shifts included the transition from the Industry Standard Architecture (ISA) bus to the Peripheral Component Interconnect (PCI) bus in the mid-1990s, introduced by Intel in 1992, which offered superior bandwidth (up to 133 MB/s) and plug-and-play support, alleviating CPU bottlenecks in data transfers. Simultaneously, wireless NICs emerged with the IEEE 802.11 standard ratified in 1997, enabling 1-2 Mbps connections over radio frequencies and spurring the development of PCMCIA and later PCI-based Wi-Fi cards for mobile computing. Since the 2000s, Intel, Realtek, and Broadcom have dominated NIC production, with Intel's PRO/1000 series and Broadcom's acquisitions solidifying their market leadership through integrated chipsets and cost-effective designs.[24][25] IEEE standardization efforts continued into the pre-2020s era, culminating in the 802.3ae amendment for 10 Gigabit Ethernet in 2002 and the 802.3an for 10GBASE-T over copper in 2006, which extended high-speed capabilities to legacy cabling and boosted data center NIC deployments. The 2010s introduced virtual NICs (vNICs) amid rising server virtualization, with technologies like Single Root I/O Virtualization (SR-IOV) allowing direct hardware passthrough to virtual machines, as demonstrated in early 10 GbE implementations by vendors like Neterion, thereby minimizing hypervisor overhead in cloud environments.[22][26]Design and Components

Hardware Architecture

A network interface controller (NIC) typically integrates a core processing unit, often implemented as an application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) or microcontroller, responsible for handling packet processing tasks such as framing, error checking, and media access control (MAC) layer operations. This central component interfaces with a physical layer (PHY) chip, which manages signal encoding and decoding to convert digital data into analog signals suitable for transmission over the network medium and vice versa. Additionally, NICs incorporate on-board memory buffers, commonly using static random-access memory (SRAM) for temporary packet queuing and storage, with typical capacities ranging from 1 to 2 MB in commodity designs to handle bursty traffic without overwhelming the host system.[4][27] Host integration occurs primarily through bus interfaces, with Peripheral Component Interconnect Express (PCIe) serving as the dominant standard since the early 2000s, enabling high-bandwidth data transfer between the NIC and the system's CPU or memory. PCIe has evolved, with version 6.0 available as of 2025 supporting up to 64 GT/s per lane and aggregate bandwidths of 256 GB/s in x16 configurations (128 GB/s per direction), building on PCIe 5.0's 32 GT/s, which is essential for high-speed NICs in data-intensive applications.[28][29][30] NICs are available in various form factors to suit different deployment needs, including PCIe add-in cards for server expansions, onboard chipsets such as the Intel i219 integrated into motherboards for desktop and laptop systems, and USB dongles for temporary or mobile connectivity. High-speed designs, particularly those supporting 10 GbE or above, demand careful management of power requirements—often up to 10-25 W—and heat dissipation, frequently addressed through aluminum heatsinks or active cooling to prevent thermal throttling.[31][32][33] Specialized elements enhance reliability and functionality; for wired Ethernet NICs, magnetics modules provide electrical isolation between the device and the network cable, ensuring safety by preventing ground loops and offering common-mode noise rejection, while also performing signal balancing and impedance matching. In wireless NICs, radio frequency (RF) modules handle modulation and amplification, paired with integrated or external antennas to transmit and receive electromagnetic signals across frequency bands like 2.4 GHz or 5 GHz. Firmware for boot-time configuration, including MAC address storage and initialization parameters, is typically held in electrically erasable programmable read-only memory (EEPROM), allowing non-volatile updates without host intervention.[34][35][36] From a manufacturing perspective, modern NICs leverage advanced silicon processes, such as 7 nm nodes introduced in the 2020s, to achieve higher transistor densities, improved power efficiency, and greater performance in compact dies, as seen in data center-oriented designs combining ASICs with field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs); by 2025, advanced nodes like 3 nm and 2 nm are employed for even higher efficiency and performance in compact dies. FPGAs enable programmable NICs in data centers by allowing customizable packet processing pipelines directly in hardware, offloading tasks like encryption or load balancing to reduce latency and CPU overhead.[37][38][39]Physical Layer Interfaces

Network interface controllers (NICs) primarily connect to wired networks through standardized physical interfaces that support various transmission media. The most common wired interface is the RJ-45 connector, which facilitates unshielded twisted-pair (UTP) cabling for Ethernet standards ranging from 10BASE-T to higher speeds. For instance, Category 5e or 6 cabling supports up to 1 Gbps over distances of 100 meters, while Category 8 cabling enables 40 Gbps operation over shorter reaches of up to 30 meters using the same RJ-45 connector, ensuring compatibility with existing infrastructure.[40][41] For longer distances and higher bandwidths, fiber optic interfaces utilize pluggable transceivers such as Small Form-factor Pluggable (SFP) or Quad SFP (QSFP) modules. These support multimode or single-mode fiber, with examples like the 100GBASE-SR4 standard achieving 100 Gbps over parallel multimode fiber up to 100 meters using MPO connectors.[42] Wireless NICs incorporate built-in antennas or connectors for radio frequency transmission, enabling cable-free connectivity. Wi-Fi interfaces adhere to IEEE 802.11 standards, with modern implementations supporting IEEE 802.11be (Wi-Fi 7), along with prior standards like 802.11ax (Wi-Fi 6/6E), providing speeds up to 40 Gbps through advanced MIMO and wider channels over 2.4, 5, 6, and higher bands where applicable. Bluetooth modules, often integrated into the same chipset, use low-energy variants like Bluetooth 6.1 for short-range pairing and data transfer up to 2 Mbps, with added features for precise location tracking. Some advanced NICs integrate cellular modems, such as 5G sub-6 GHz modules compliant with 3GPP Release 18 (5G-Advanced), allowing seamless fallback between wired, Wi-Fi, and mobile networks in devices like laptops.[43][44][45][46][47][48] NICs support media conversion across copper, fiber, and legacy coaxial cabling, with auto-negotiation protocols defined in IEEE 802.3 ensuring optimal speed and duplex modes. This allows automatic detection of link capabilities, such as 10/100/1000 Mbps full-duplex over twisted-pair or fiber, while maintaining backward compatibility with older media like 10BASE2 coaxial using BNC connectors from early Ethernet deployments. Connector standards have evolved from the Attachment Unit Interface (AUI) DB-15 in original 10 Mbps Ethernet to ubiquitous RJ-45 for twisted-pair, and now to compact M.2 slots in mobile and embedded devices for integrating Wi-Fi and Bluetooth modules. Industrial applications often employ ruggedized variants, such as sealed RJ-45 or M12 connectors, to withstand harsh environments like vibration, dust, and extreme temperatures.[49][50][51] Compatibility features extend to legacy media support and power delivery. Ethernet NICs maintain backward compatibility with prior cable types and speeds through auto-negotiation, enabling mixed environments without full upgrades. Additionally, many NICs facilitate Power over Ethernet (PoE) as powered devices (PDs), drawing up to 30 W (IEEE 802.3at) or 90 W (802.3bt) over twisted-pair cabling to simplify deployment in IP cameras, VoIP phones, and wireless access points.[49][52]Operation and Integration

Data Processing Workflow

The data reception process in a network interface controller (NIC) commences at the physical layer (PHY), where incoming analog signals—typically electrical over twisted-pair cabling or optical via fiber—are detected, amplified, and decoded into a serial stream of digital bits. This involves clock recovery and synchronization to the 7-byte preamble followed by the 1-byte start frame delimiter (SFD) as defined in IEEE 802.3, ensuring alignment before the actual frame data arrives.[53] The PHY then serial-to-parallel converts the bit stream and transmits it to the media access control (MAC) sublayer through an interface such as the media independent interface (MII) or reduced MII (RMII).[54] At the MAC layer, the bit stream is reassembled into a complete Ethernet frame, including the destination and source MAC addresses, length/type field, payload, and frame check sequence (FCS). The MAC performs address filtering to determine if the frame is destined for the local host, calculates and validates the FCS using a cyclic redundancy check (CRC-32 polynomial) to detect transmission errors, and strips the preamble/SFD if valid. If the frame passes validation, it is temporarily buffered in the NIC's onboard SRAM or FIFO memory to handle burst arrivals and prevent overflow.[55] For efficient transfer to the host system, the NIC employs direct memory access (DMA) engines to move the frame data from its internal buffers to pre-allocated locations in host RAM, using descriptor rings configured for scatter-gather operations to manage multiple packets. Upon completion of the DMA transfer, the NIC signals packet arrival to the host via an interrupt or polling mechanism, queuing the frame for processing by the operating system's network stack.[4] Error handling during reception is primarily managed at the hardware level through FCS validation; frames with mismatched CRC are silently discarded by the MAC to avoid corrupting higher-layer protocols, with any necessary retransmissions triggered by transport-layer mechanisms such as TCP acknowledgments. In half-duplex modes—now largely legacy but still supported in some environments—the MAC also implements carrier sense multiple access with collision detection (CSMA/CD), monitoring for collisions during reception and invoking backoff algorithms if detected.[56] Flow control is facilitated by IEEE 802.3x pause frames, where a receiving NIC can insert a MAC control frame into the stream to request the sender to halt transmission temporarily if its receive buffers approach capacity, resuming via a subsequent pause frame with zero duration.[57] The transmission process operates in reverse, initiating with DMA transfers from host RAM to the NIC's transmit buffers, where the host system (via driver-configured descriptors) supplies raw packet data for queuing in multiple transmit rings to support parallel processing. The MAC then encapsulates the data into an Ethernet frame by prepending the destination/source MAC addresses, length/type, and payload, before appending the FCS computed via CRC-32 for integrity assurance. This framed data is passed to the PHY, which performs parallel-to-serial conversion, adds the preamble and SFD, and encodes the bits into analog signals suitable for the medium—such as Manchester encoding for 10BASE-T or 4B/5B with NRZI for Fast Ethernet—while adhering to IEEE 802.3 signaling specifications. The PHY transmits these signals onto the network, with the MAC monitoring for successful delivery in half-duplex scenarios via CSMA/CD to detect and retry collisions.[53][55] Overall, the NIC's workflow forms a high-level pipeline from physical signals to host integration: incoming signals traverse PHY decoding and MAC validation before DMA handoff to the OS stack, while outbound data follows the inverse path with hardware-accelerated framing and encoding, incorporating queue management across multiple ingress/egress queues to handle concurrent packet flows and maintain low latency. The driver plays a brief role in initializing DMA descriptors for these transfers, but the core processing remains autonomous to the NIC hardware.[4]Software and Driver Interaction

Network interface controllers (NICs) interact with operating systems primarily through dedicated software drivers that manage hardware operations and facilitate data exchange. In Windows environments, the Network Driver Interface Specification (NDIS) serves as the standard kernel-mode framework for NIC drivers, where miniport drivers handle low-level hardware control while protocol drivers, such as those for TCP/IP, interface with higher-level network stacks to process incoming and outgoing packets. This layered architecture ensures efficient communication between the NIC hardware and the OS kernel, abstracting hardware specifics to enable consistent protocol handling across diverse NIC vendors. Similarly, in Linux, kernel-mode drivers like the e1000 series for Intel Ethernet adapters register as netdevice structures within the kernel's networking subsystem, providing hooks for packet transmission, reception, and interrupt handling that integrate seamlessly with the TCP/IP stack.[58] For scenarios demanding higher performance and lower latency, user-space libraries such as the Data Plane Development Kit (DPDK) enable direct NIC access by bypassing the kernel networking stack entirely. DPDK employs poll-mode drivers (PMDs) that run in user space, utilizing techniques like hugepages for memory management and ring buffers for efficient packet I/O, allowing applications to control NIC operations without kernel overhead.[59] This approach is particularly useful in high-throughput environments like data centers, where it supports multi-core processing and vendor-agnostic NIC compatibility through standardized APIs. Configuration of NICs via software drivers involves setting key parameters to align with network requirements and optimize performance. Drivers allow adjustment of the MAC address for identification on local networks, typically through OS-specific commands likeip link in Linux to set a custom address or spoofing for testing. The Maximum Transmission Unit (MTU) size can be configured to support standard 1500-byte frames or larger jumbo frames up to 9000 bytes, reducing overhead in high-bandwidth scenarios by minimizing segmentation; this is achieved via tools like ethtool or ip link set mtu.[60] VLAN tagging is enabled through driver support for IEEE 802.1Q, adding tags to frames for segmentation, often configured using ip link add for virtual subinterfaces or NetworkManager in enterprise setups.

API standards underpin this software interaction, ensuring portability and modularity. In Windows, NDIS defines entry points for driver initialization, status reporting, and data transfer, allowing the TCP/IP protocol stack to bind to NIC miniports for layered protocol processing without direct hardware access.[61] Linux's netdevice API provides similar abstractions through structures like struct net_device, which expose methods for opening/closing interfaces, queuing packets, and handling statistics, integrating NIC drivers into the broader kernel network stack for protocol-agnostic operation.[62]

Virtualization support extends NIC functionality in virtualized environments, where drivers enable multiple virtual NICs (vNICs) to share physical hardware efficiently. Single Root I/O Virtualization (SR-IOV) allows a physical NIC to appear as multiple virtual functions directly assignable to virtual machines (VMs), minimizing hypervisor involvement and providing near-native performance through hardware isolation of PCI Express resources.[63] Paravirtualization drivers, such as virtio-net, optimize this by implementing a semi-virtual interface where the guest OS uses a simplified driver that communicates with the hypervisor via a shared memory ring, reducing emulation overhead compared to full device emulation.

Troubleshooting NIC software interactions often centers on driver maintenance and diagnostic tools to resolve compatibility issues. Regular driver updates are essential to address bugs, support new hardware features, and ensure OS kernel compatibility, with vendors like Intel providing version-specific releases such as e1000e 3.8.7 for legacy support.[58] Tools like ethtool in Linux facilitate diagnostics by querying driver versions (ethtool -i), displaying statistics (ethtool -S), and testing link status, helping identify issues like interrupt coalescing misconfigurations or firmware mismatches.[64] In Windows, Device Manager and NDIS logs aid similar checks, emphasizing the need for verified driver-firmware pairings to prevent connectivity failures.