Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Occipital bone

View on Wikipedia| Occipital bone | |

|---|---|

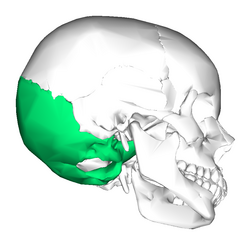

Position of occipital bone | |

Animation of the occipital bone | |

| Details | |

| Articulations | The two parietals, the two temporals, the sphenoid, and the atlas |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | os occipitale |

| MeSH | D009777 |

| TA98 | A02.1.04.001 |

| TA2 | 552 |

| FMA | 52735 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The occipital bone (/ˌɒkˈsɪpɪtəl/) is a cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone lies over the occipital lobes of the cerebrum. At the base of the skull in the occipital bone, there is a large oval opening called the foramen magnum, which allows the passage of the spinal cord.

Like the other cranial bones, it is classed as a flat bone. Due to its many attachments and features, the occipital bone is described in terms of separate parts. From its front to the back is the basilar part, also called the basioccipital, at the sides of the foramen magnum are the lateral parts, also called the exoccipitals, and the back is named as the squamous part. The basilar part is a thick, somewhat quadrilateral piece in front of the foramen magnum and directed towards the pharynx. The squamous part is the curved, expanded plate behind the foramen magnum and is the largest part of the occipital bone.

Due to its embryonic derivation from paraxial mesoderm (as opposed to neural crest, from which many other craniofacial bones are derived), it has been posited that "the occipital bone as a whole could be considered as a giant vertebra enlarged to support the brain."[1]

Structure

[edit]The occipital bone, like the other seven cranial bones, has outer and inner layers (also called plates or tables) of cortical bone tissue between which is the cancellous bone tissue known in the cranial bones as diploë. The bone is especially thick at the ridges, protuberances, condyles, and anterior part of the basilar part; in the inferior cerebellar fossae it is thin, semitransparent, and without diploë.

Outer surface

[edit]

Near the middle of the outer surface of the squamous part of the occipital (the largest part) there is a prominence – the external occipital protuberance. The highest point of this is called the inion.

From the inion, along the midline of the squamous part until the foramen magnum, runs a ridge – the external occipital crest (also called the medial nuchal line) and this gives attachment to the nuchal ligament.

Running across the outside of the occipital bone are three curved lines and one line (the medial line) that runs down to the foramen magnum. These are known as the nuchal lines which give attachment to various ligaments and muscles. They are named as the highest, superior and inferior nuchal lines. The inferior nuchal line runs across the midpoint of the median nuchal line. The area above the highest nuchal line is termed the occipital plane and the area below this line is termed the nuchal plane.

Inner surface

[edit]

The inner surface of the occipital bone forms the base of the posterior cranial fossa. The foramen magnum is a large hole situated in the middle, with the clivus, a smooth part of the occipital bone travelling upwards in front of it. The median internal occipital crest travels behind it to the internal occipital protuberance, and serves as a point of attachment to the falx cerebri.

To the sides of the foramen sitting at the junction between the lateral and base of the occipital bone are the hypoglossal canals. Further out, at each junction between the occipital and petrous portion of the temporal bone lies a jugular foramen.[2]

The inner surface of the occipital bone is marked by dividing lines as shallow ridges, that form four fossae or depressions. The lines are called the cruciform (cross-shaped) eminence.

At the midpoint where the lines intersect a raised part is formed called the internal occipital protuberance. From each side of this eminence runs a groove for the transverse sinuses.

There are two midline skull landmarks at the foramen magnum. The basion is the most anterior point of the opening and the opisthion is the point on the opposite posterior part. The basion lines up with the dens.

Foramen magnum

[edit]The foramen magnum (Latin: large hole) is a large oval foramen longest front to back; it is wider behind than in front where it is encroached upon by the occipital condyles. The clivus, a smooth bony section, travels upwards on the front surface of the foramen, and the median internal occipital crest travels behind it.[3]

Through the foramen passes the medulla oblongata and its membranes, the accessory nerves, the vertebral arteries, the anterior and posterior spinal arteries, the tectorial membrane and the alar ligaments.

Angles

[edit]The superior angle of the occipital bone articulates with the occipital angles of the parietal bones and, in the fetal skull, corresponds in position with the posterior fontanelle.

The lateral angles are situated at the extremities of the groove for the transverse sinuses: each is received into the interval between the mastoid angle of the parietal bone, and the mastoid portion of the temporal bone.

The inferior angle is fused with the body of the sphenoid bone.

Borders

[edit]The superior borders extend from the superior to the lateral angles: they are deeply serrated for articulation with the occipital borders of the parietals, and form by this union the lambdoidal suture.

The inferior borders extend from the lateral angles to the inferior angle; the upper half of each articulates with the mastoid portion of the corresponding temporal, the lower half with the petrous part of the same bone.

These two portions of the inferior border are separated from one another by the jugular process, the notch on the anterior surface of which forms the posterior part of the jugular foramen.

Sutures

[edit]-

Lambdoid suture

-

Occipitomastoid suture

The lambdoid suture joins the occipital bone to the parietal bones.

The occipitomastoid suture joins the occipital bone and mastoid portion of the temporal bone.

The sphenobasilar suture joins the basilar part of the occipital bone and the back of the sphenoid bone body.

The petrous-basilar suture joins the side edge of the basilar part of the occipital bone to the petrous-part of the temporal bone.

Development

[edit]

The occipital plane [Fig. 3] of the squamous part of the occipital bone is developed in membrane, and may remain separate throughout life when it constitutes the interparietal bone; the rest of the bone is developed in cartilage.

The number of nuclei for the occipital plane is usually given as four, two appearing near the middle line about the second month, and two some little distance from the middle line about the third month of fetal life.

The nuchal plane of the squamous part is ossified from two centers, which appear about the seventh week of fetal life and soon unite to form a single piece.

Union of the upper and lower portions of the squamous part takes place in the third month of fetal life.

An occasional centre (Kerckring) appears in the posterior margin of the foramen magnum during the fifth month; this forms a separate ossicle (sometimes double) which unites with the rest of the squamous part before birth.

Each of the lateral parts begins to ossify from a single center during the eighth week of fetal life. The basilar portion is ossified from two centers, one in front of the other; these appear about the sixth week of fetal life and rapidly coalesce.

The occipital plane is said to be ossified from two centers and the basilar portion from one.

About the fourth year the squamous part and the two lateral parts unite, and by about the sixth year the bone consists of a single piece. Between the 18th and 25th years the occipital and sphenoid bone become united, forming a single bone.

Clinical significance

[edit]Trauma to the occiput can cause a fracture of the base of the skull, called a basilar skull fracture. The basion-dens line as seen on a radiograph is the distance between the basion and the top of the dens, used in the diagnosis of dissociation injuries.[4]

Genetic disorders can cause a prominent occiput as found in Edwards syndrome, and Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome.

The identification of the location of the fetal occiput is important in delivery.

Etymology

[edit]Occipital stems from Latin occiput "back of the skull", from ob "against, behind" + caput "head". Distinguished from sinciput (anterior part of the skull).[5]

Other animals

[edit]In many animals these parts stay separate throughout life; for example, in the dog as four parts: squamous part (supraoccipital); lateral parts–left and right parts (exoccipital); basilar part (basioccipital).

The occipital bone is part of the endocranium, the most basal portion of the skull. In Chondrichthyes and Agnatha, the occipital does not form as a separate element, but remains part of the chondrocranium throughout life. In most higher vertebrates, the foramen magnum is surrounded by a ring of four bones.

The basioccipital lies in front of the opening, the two exoccipital condyles lie to either side, and the larger supraoccipital lies to the posterior, and forms at least part of the rear of the cranium. In many bony fish and amphibians, the supraoccipital is never ossified, and remains as cartilage throughout life. In primitive forms the basioccipital and exoccipitals somewhat resemble the centrum and neural arches of a vertebra, and form in a similar manner in the embryo. Together, these latter bones usually form a single concave circular condyle for the articulation of the first vertebra.[6]

In mammals, however, the condyle has divided in two, a pattern otherwise seen only in a few amphibians.

Most mammals also have a single fused occipital bone, formed from the four separate elements around the foramen magnum, along with the paired postparietal bones that form the rear of the cranial roof in other vertebrates.[6]

Additional images

[edit]-

Position of occipital bone (shown in green). Animation.

-

Outer surface

-

Inner surface. Frontal bone and parietal bones are removed.

-

Occipital bone

-

Occipital bone

-

Median sagittal section through the occipital bone and first three cervical vertebræ

-

Basilar part

-

Occipital bone

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Books

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 129 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 129 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- Susan Standring; Neil R. Borley; et al., eds. (2008). Gray's anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice (40th ed.). London: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-8089-2371-8.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Nie, Xuguang (2005). "Cranial base in craniofacial development: Developmental features, influence on facial growth, anomaly, and molecular basis". Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 63 (3): 130. doi:10.1080/00016350510019847. PMID 16191905. S2CID 1091809 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ^ Gray's Anatomy 2008, p. 424-425.

- ^ Gray's Anatomy 2008, p. 425.

- ^ Hacking, Craig. "Basion-dens interval | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". radiopaedia.org. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ "occipital" A Dictionary of Zoology. Ed. Michael Allaby. Oxford University Press 2009

- ^ a b Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 221–244. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

External links

[edit] Media related to Occipital bones at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Occipital bones at Wikimedia Commons

Occipital bone

View on GrokipediaOverview

Location and general description

The occipital bone is a single, unpaired cranial bone that forms the posterior and inferior aspects of the cranium, serving as the primary structure of the occiput. It is classified as a flat bone, exhibiting a trapezoidal shape that is shallowly curved to accommodate the posterior cranial fossa. This positioning allows it to contribute significantly to both the calvaria (the upper portion of the skull enclosing the cerebral hemispheres) and the cranial base, where it supports the weight of the head and facilitates the transition from the skull to the vertebral column.[1] The bone articulates superiorly with the two parietal bones along the lambdoid suture, inferolaterally with the temporal bones via the occipitomastoid sutures, anteriorly with the body of the sphenoid bone, and inferiorly with the atlas (first cervical vertebra) through its occipital condyles. These articulations integrate the occipital bone into the overall cranial architecture, enabling stability and mobility at the craniovertebral junction. In adults, the bone typically exhibits a thickness of about 10 mm at its central protuberance, varying regionally to balance protection and weight.[1][3] The occipital bone plays a crucial role in housing and protecting the brainstem, which passes through its large central opening, as well as the cerebellum and the occipital lobes of the cerebrum within the posterior cranial fossa. This composition provides robust mechanical support while minimizing overall skull weight.[1][2][4]Etymology

The term "occipital bone" derives from the Latin "occiput," meaning "back of the head" or "back of the skull," with the adjectival suffix "-al" indicating relation to that structure.[5] This nomenclature reflects the bone's position at the posterior aspect of the cranium, a convention established in early modern anatomical literature. The Latin "occiput" itself combines "ob-" (against) and "caput" (head), emphasizing its location opposite the face.[6] In historical anatomical texts, the bone is described in Andreas Vesalius's seminal 1543 work De humani corporis fabrica libri septem as one of the primary cranial bones forming the skull's base and posterior wall.[7] Vesalius's precise illustrations and descriptions marked a shift from medieval reliance on ancient authorities like Galen, standardizing Latin terminology that persists in modern anatomy. This naming convention influenced subsequent works, such as those by anatomists like Fabricius ab Aquapendente, solidifying "os occipitale" as the formal Latin designation.[8] Related terms applied to the bone's external features include "nuchal," derived from the Medieval Latin "nuchalis," based on "nucha" meaning the nape of the neck, ultimately from Arabic "nuḵāʕ" (spinal cord or marrow).[9] In anatomy, "nuchal" specifically denotes structures like the nuchal lines and protuberance on the occipital bone's outer surface, highlighting its association with the posterior neck region. This etymological link underscores the bone's role in connecting the skull to the cervical vertebrae, though the term's adoption in Western anatomy dates to the 16th century alongside Vesalius's reforms.[10]Anatomy

External surface

The external surface of the occipital bone forms the convex posterior aspect of the cranium, characterized by prominent ridges and projections that primarily serve as attachment sites for muscles and ligaments of the neck. This surface is divided into a central squamous part and bilateral lateral parts, with the squamous portion extending superiorly to articulate with the parietal bones along the lambdoid suture.[1][11] At the midpoint of the superior aspect of the squamous part lies the external occipital protuberance, a palpable midline bony projection also known as the inion at its apex, which marks the highest point of the bone and provides attachment for the nuchal ligament and trapezius muscle.[1][12] Extending laterally from this protuberance are the nuchal lines, a series of curved ridges that traverse the external surface. The supreme (or highest) nuchal line originates near the protuberance and arcs laterally toward the lambdoid suture, serving as the origin for the epicranial aponeurosis. Immediately inferior to it, the superior nuchal line follows a similar path but curves more prominently, attaching muscles such as the trapezius, splenius capitis, and sternocleidomastoid. The inferior nuchal line, located further below, intersects the median nuchal line and provides insertion for muscles including the obliquus capitis superior and rectus capitis posterior major and minor. The median nuchal line, a vertical crest, descends from the external occipital protuberance toward the foramen magnum, anchoring the nuchal ligament.[11][13][12] The squamous part constitutes the broad, expanded posterior wall of the bone, curving gently to accommodate overlying soft tissues. Laterally, it transitions into the two lateral parts, each featuring a jugular process that projects forward from the region of the occipital condyle; this process bears a jugular notch on its anterior margin, contributing to the boundary of the jugular foramen and providing attachment for the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. Additionally, shallow occipital grooves traverse the external surface near the superior nuchal line, accommodating the course of the occipital artery and its accompanying vein.[1][11][14]Internal surface

The internal surface of the occipital bone is concave, forming the roof and posterior wall of the posterior cranial fossa, which accommodates the cerebellum and brainstem.[11][12] A prominent cruciform eminence, consisting of intersecting ridges, is located on this surface and divides it into four fossae.[13][15] At the center of the cruciform eminence lies the internal occipital protuberance, a midline elevation that marks the site of the confluence of the dural venous sinuses, known as the torcular Herophili.[11][12] The upper two fossae, triangular in shape, receive impressions from the occipital lobes of the cerebrum, while the lower two, more rectangular fossae bear impressions from the cerebellar hemispheres.[16][15] The cruciform eminence gives rise to several grooves that house the dural venous sinuses. The vertical limb, formed by the internal occipital crest, contains the groove for the occipital sinus and extends inferiorly toward the foramen magnum.[11][13] The horizontal limb includes bilateral grooves for the transverse sinuses, which curve laterally from the protuberance and continue as grooves for the sigmoid sinuses toward the jugular foramina.[12][15] Superiorly, the sagittal sulcus extends from the protuberance for the superior sagittal sinus.[11][16] On the lateral aspects of the internal surface, near the base, are the openings of the hypoglossal canals, which pierce the bone just superior to the occipital condyles and transmit the hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII) and a meningeal branch of the ascending pharyngeal artery.[13][11] Adjacent to these, the jugular foramina are formed at the junction with the temporal bone, serving as passages for cranial nerves IX, X, and XI, as well as the inferior petrosal and sigmoid sinuses.[12][15] The lower fossae exhibit irregular impressions from the overlying cerebellar hemispheres, and the internal occipital crest provides attachment for the falx cerebelli, a dural fold that separates the cerebellar hemispheres.[16][13]Foramen magnum and other openings

The foramen magnum represents the central and largest aperture in the occipital bone, typically presenting as an oval opening with average anteroposterior dimensions of approximately 3.1 cm and transverse dimensions of 2.7 cm, though these measurements exhibit sexual dimorphism and individual variability.[17] This opening is positioned in the basal portion of the bone, bounded anteriorly by the basilar part, laterally by the condylar parts, and posteriorly by the squama, facilitating the transition between the cranial cavity and the vertebral canal.[18] It transmits critical neurovascular structures, including the medulla oblongata continuous with the spinal cord, the meninges, the spinal roots of the accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI), the vertebral arteries, the anterior and posterior spinal arteries, the tectorial membrane, and the alar ligaments.[18] Anatomical variations in the foramen magnum include differences in shape (such as ovoid, rhomboid, or heart-shaped) and occasional asymmetry or protrusion of the occipital condyles into its margins.[18] Peripheral to the foramen magnum, the occipital bone features several smaller openings that serve as conduits for nerves and vessels. The hypoglossal canals, a pair of bony passages located anterior to the occipital condyles within the condylar parts of the bone, transmit the hypoglossal nerves (cranial nerve XII) and meningeal branches of the ascending pharyngeal artery.[1] These canals form during the ossification of the exoccipital segments and are oriented anterolaterally toward the base of the skull.[18] The condylar canals, positioned posterior to the occipital condyles, are variable foramina that house the condylar emissary veins, which drain blood from the sigmoid sinus and occipital sinus to the suboccipital venous plexus, aiding in intracranial venous outflow.[1] These canals may present as a single structure or as multiple smaller clustered openings, with absence in some individuals representing a common variation.[1] At the posterolateral margins of the occipital bone, the jugular foramina are formed in conjunction with the petrous temporal bones, creating irregular, keyhole-shaped apertures that accommodate the glossopharyngeal (CN IX), vagus (CN X), and accessory (CN XI) nerves, as well as the internal jugular vein and its meningeal branches.[1] The occipital contribution to this foramen includes the jugular process, which partially roofs the opening and may feature an oblique groove on the adjacent jugular tubercle for the passage of these structures.[1] Additional anatomical variations in these openings include persistent paramedian foramina adjacent to the condylar canals, which can represent incomplete fusion of embryonic ossification centers and potentially alter venous drainage patterns.[19]Borders, angles, and sutures

The occipital bone features a trapezoidal shape with distinct borders that facilitate its articulations with adjacent cranial bones. The superior border, also known as the lambdoid border, is serrated and extends between the two lateral angles, articulating with the occipital borders of the left and right parietal bones to form the lambdoid suture.[11] This suture is characterized by its inverted V-shape, resembling the Greek letter lambda, and it converges posteriorly with the sagittal suture.[1] The inferolateral borders of the occipital bone are positioned along its posterolateral aspects and connect with the mastoid portions of the temporal bones. These borders form the occipitomastoid suture, a jagged line that joins the occipital bone to the temporal bone, while the adjacent parietomastoid suture links the temporal bone to the parietal bone nearby.[11][20] The petro-occipital suture, located more inferiorly, further connects the petrous portion of the temporal bone to the occipital bone.[20] The occipital bone has four prominent angles defined by the intersections of these borders and sutures. The superior angle, termed lambda, occurs at the midpoint of the superior border where the lambdoid suture meets the sagittal suture, serving as a key craniometric landmark.[1] The lateral angles are located at the asterion, the point of convergence between the lambdoid, occipitomastoid, and parietomastoid sutures, which marks the site of the former posterior fontanelle.[21] The inferolateral angles feature the jugular processes, paired bony projections that extend laterally from the region between the occipital condyles and the jugular notches; these processes contribute to the posterior margins of the jugular foramina by articulating with the temporal bones.[11] In terms of articulations, the occipital bone connects superiorly and laterally with the parietal and temporal bones via the aforementioned sutures, while its inferior aspect includes the paired occipital condyles that articulate with the superior articular facets of the atlas vertebra (C1), forming the atlanto-occipital joint and enabling flexion and extension of the head.[1] Regarding suture fusion, the petro-occipital fissure—a cartilaginous gap between the petrous temporal bone and the occipital bone—undergoes gradual ossification starting in early adulthood and continuing into later life, though it may remain partially unossified even in older individuals.[22]Development

Ossification process

The ossification of the occipital bone occurs through a combination of intramembranous and endochondral processes during embryonic and early fetal development, with distinct centers forming for its major portions. The squamous portion undergoes intramembranous ossification, beginning around the 8th gestational week from primary centers in the interparietal region that rapidly fuse into a more unified structure by the 9th to 10th week.[23] This process directly converts mesenchymal tissue into bone without an intervening cartilage model, contributing to the posterior vault of the cranium.[4] In contrast, the lateral (condylar) parts and basilar part develop via endochondral ossification, relying on prior cartilage formation from the chondrocranium. The basilar part derives from the parachordal region of the chondrocranium, where cartilage centers appear as early as the 6th embryonic week; ossification then initiates from two bilateral centers around the 11th gestational week, progressing anteriorly to support the cranial base.[23][24] The two lateral parts, flanking the foramen magnum, form from paired cartilage models with primary ossification centers emerging at approximately the 8th gestational week, expanding linearly through the fetal period to form the occipital condyles.[24] These endochondral centers arise from neural crest-derived mesenchyme and sclerotomal contributions, ensuring structural integrity around the brainstem.[4] Molecular regulators, including Hox genes and BMP signaling pathways, play critical roles in patterning these ossification centers. Hox genes, such as those in the Hoxa and Hoxd clusters, establish anterior-posterior identity in the posterior cranial base, influencing the specification of occipital segments from somitic mesoderm.[25] BMP signaling, particularly through Bmp2 and Bmp4, promotes mesenchymal condensation and differentiation in cranial neural crest cells, coordinating the transition from cartilage to bone in endochondral regions while interacting with Hox factors to refine skeletal boundaries.[26] Disruptions in these pathways can alter ossification timing and morphology.[27] Fetal variations in occipital ossification are influenced by early neural tube closure, which occurs by the 4th week and provides the foundational enclosure for cranial mesenchyme. Incomplete closure, as in anencephaly, leads to absent or rudimentary squamous and basilar ossification centers due to lack of inductive signals from the neural tissue.[4] Such variations highlight the interdependence of neural and skeletal development in the occipital region.[28]Fusion and growth

The postnatal development of the occipital bone involves the progressive fusion of its multiple ossification centers into a unified structure. The lateral parts initially fuse with the squamous (interparietal) part between approximately 1 and 5 years of age, forming the main body of the bone.[29][30] Subsequently, the basilar part unites with the lateral parts around 5 to 6 years, completing the initial integration of the bone's major components.[29][30] Full unification of all parts, including the final closure of associated synchondroses, typically occurs by 25 to 30 years of age.[29] Growth of the occipital bone during this period primarily occurs through appositional bone deposition along the sutures and synchondroses, allowing for expansion and remodeling to accommodate brain growth and cranial vault changes.[31] This process is further modulated by the flexion of the cranial base, particularly through the activity at the spheno-occipital synchondrosis, which contributes to the overall angulation and elongation of the posterior skull base.[32][33] Sexual dimorphism manifests in the dimensions of the foramen magnum, with males exhibiting a larger average transverse diameter (approximately 3.1 cm) compared to females (approximately 2.9 cm), reflecting broader cranial differences.[34][35] In rare cases, anomalies such as incomplete union of the basilar part with the lateral components can persist, potentially resulting in segmentation defects or accessory ossicles within the occipital region.[36]Function

Structural support

The occipital bone functions as a keystone in the cranial vault, providing essential structural integrity and distributing biomechanical forces from head impacts to safeguard the enclosed brain tissue. This role is facilitated by its thick cortical bone layer, which measures 2-4 mm in thickness and offers high rigidity to resist deformation under load.[37] Central to its supportive function is the precise alignment of the foramen magnum with the spinal column, which balances the head's weight—approximately 4.5-5 kg in adults—while enabling efficient weight transfer to the cervical vertebrae. This positioning optimizes postural stability and reduces undue stress on the neck during everyday movements and upright stance.[18][38] Complementing these features are the bone's material properties, with a dense compact outer layer enclosing a spongy diploë interior that enhances shock absorption. The trabecular structure of the diploë dissipates impact energy, minimizing transmission to underlying neural structures and bolstering the skull's resilience against trauma.[39][40]Muscle and ligament attachments

The occipital bone serves as a key attachment site for several suboccipital muscles, which originate from the upper cervical vertebrae and insert onto its posterior surface, facilitating precise head movements. The rectus capitis posterior major muscle originates from the spinous process of the axis (C2 vertebra) and inserts onto the inferior nuchal line of the occipital bone, while the rectus capitis posterior minor arises from the posterior tubercle of the atlas (C1 vertebra) and attaches to the adjacent region medial to the inferior nuchal line near the foramen magnum.[41] The obliquus capitis superior muscle originates from the transverse process of the atlas and inserts onto the occipital bone between the superior and inferior nuchal lines, whereas the obliquus capitis inferior, though not directly attaching to the occipital bone, connects the spinous process of the axis to the transverse process of the atlas, contributing to the suboccipital muscular complex that influences occipital motion.[41] Ligamentous attachments further stabilize the occipital bone in relation to the cervical spine. The ligamentum nuchae attaches along the external occipital protuberance and the median nuchal line, providing midline support and limiting excessive flexion of the head.[1] Within the region of the foramen magnum, the tectorial membrane anchors to the basilar part of the occipital bone, extending superiorly to reinforce the atlanto-occipital joint and prevent anterior displacement of the cervical vertebrae.[1] These muscular and ligamentous attachments play essential roles in neck movements through the atlanto-occipital joint, which primarily permits flexion and extension (nodding motion) of the head, with approximately 15° to 20° of range, while also contributing to limited rotation and lateral flexion.[42] The rectus capitis posterior muscles and obliquus capitis superior enable head extension and ipsilateral rotation, whereas the ligamentum nuchae and tectorial membrane enhance stability during these dynamic actions.[41] Innervation to these attachments arises from branches of the suboccipital nerve (dorsal ramus of C1), which supplies the rectus capitis posterior major and minor, as well as the obliquus capitis superior and inferior muscles.[41] Blood supply to the suboccipital muscles is provided by muscular branches of the vertebral artery (V3 segment), ensuring adequate perfusion for their postural and motor functions.[41]Clinical significance

Trauma and fractures

The occipital bone is particularly susceptible to trauma in basilar skull fractures, which commonly result from high-impact events such as falls from height or motor vehicle accidents (MVAs).[43] These fractures often involve a ring-like pattern encircling the foramen magnum, where axial loading forces transmitted through the cervical spine cause separation of the occipital bone's rim from the rest of the skull base.[44] The mechanism typically includes hyperextension, hyperflexion, or rotational forces that shear the bone at its junction with adjacent structures like the temporal and sphenoid bones.[44] Characteristic clinical signs of basilar skull fractures involving the occipital bone include Battle's sign (ecchymosis over the mastoid process), raccoon eyes (periorbital ecchymosis), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea or otorrhea due to dural tears.[43] These indicators arise from hemorrhage tracking along fascial planes and potential communication between the subarachnoid space and external environment. Mortality risks are elevated, primarily from brainstem compression or laceration, which can lead to immediate cardiorespiratory arrest or secondary complications like herniation.[43][44] Basilar skull fractures are classified as linear (simple, non-displaced cracks) or comminuted (shattered into multiple fragments), with the latter associated with higher energy impacts and worse prognosis.[43] Basilar skull fractures occur in approximately 4% of cases of severe head injury and represent 19-21% of skull fractures, underscoring their prevalence in polytrauma scenarios.[43][45] Acute management prioritizes stabilization of airway, breathing, and circulation (ABC protocol) to mitigate risks, including cervical spine immobilization to prevent further displacement.[43] Hypotension must be rigorously avoided, as it exacerbates cerebral ischemia and promotes transtentorial herniation in the context of brainstem vulnerability.[43]Congenital anomalies

Congenital anomalies of the occipital bone encompass a range of developmental abnormalities that disrupt the normal formation and integration of this structure at the craniovertebral junction, often leading to neurological complications due to compression or instability. These defects arise from disruptions in chondrocranial development during embryogenesis, affecting the basiocciput, exoccipitals, and supraoccipital components.[46][47] Platybasia involves flattening of the cranial base, characterized by an increased angle between the clivus and the plane of the foramen magnum exceeding 142°, which shortens the vertical height of the posterior cranial fossa.[48] This condition frequently coexists with basilar invagination, a congenital malformation where the odontoid process protrudes superiorly into the foramen magnum, potentially causing brainstem compression.[46][47] Basilar invagination is strongly associated with Chiari malformation type I, in which the cerebellar tonsils herniate through the foramen magnum, exacerbating syringomyelia or hydrocephalus in affected individuals.[49] The prevalence of Chiari malformation type I is estimated at 0.5-1% in the general population, with many cases remaining asymptomatic until adolescence when symptoms such as headaches or neck pain prompt diagnosis.[50] Genetic conditions can further predispose to occipital bone anomalies. In trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome), an extra chromosome 18 leads to craniofacial dysplasias, including a prominent occiput, widened foramen magnum, and sparse occipital bone shelves, reflecting disrupted osteogenic-neural interactions in the posterior cranial fossa.[51] Similarly, achondroplasia, caused by FGFR3 mutations, impairs condylar growth and results in hypoplasia of the occipital condyles, contributing to basilar invagination and platybasia through defective endochondral ossification at the skull base.[47][52] Occipitalization of the atlas, or atlanto-occipital assimilation, represents a congenital fusion of the atlas (C1 vertebra) to the occipital bone, which alters the biomechanics of the craniocervical junction and reduces cervical mobility.[53] This anomaly, occurring in approximately 0.08-3% of the population, can narrow the foramen magnum and predispose to instability or neurological deficits, though it often remains incidental unless symptomatic.[54][53]Diagnostic and surgical considerations

Computed tomography (CT) scanning is the primary imaging modality for detecting fractures of the occipital bone, particularly occipital condyle fractures, with a reported sensitivity of 100% in identifying these injuries.[55] High-resolution CT enables detailed assessment of bony structures and craniocervical alignment, facilitating accurate diagnosis in trauma settings.[56] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) complements CT by evaluating soft tissue involvement, such as in Chiari malformation, where it serves as the modality of choice to visualize cerebellar tonsillar herniation and associated syringomyelia.[57] Post-2015 advancements in 3D reconstructions from CT and MRI data have enhanced preoperative planning for occipital bone procedures, allowing surgeons to simulate craniectomies and customize implants for precise reconstruction.[58] Surgical access to the occipital bone often involves suboccipital craniectomy, a midline approach that removes a portion of the occipital bone to access posterior fossa tumors for resection or to perform decompression in cases of Chiari malformation.[59] This technique provides wide exposure to the cerebellum and brainstem while minimizing retraction.[60] For vascular complications like occipital condylar pseudoaneurysms, endovascular approaches offer a minimally invasive alternative, utilizing coil embolization or flow-diverting stents to preserve parent vessel patency and prevent rupture.[61] Common complications following occipital bone surgery include cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage, with rates ranging from 1.5% to 14.5% after suboccipital craniectomy, often due to dural defects.[62] Infection risk is elevated in posterior fossa procedures, necessitating prophylactic antibiotics and meticulous wound management. Postoperative monitoring typically involves intracranial pressure (ICP) devices to detect elevations from edema or hemorrhage, guiding timely interventions.[63] Recent updates in the 2020s emphasize intraoperative navigation systems, such as the StealthStation platform, which integrate real-time 3D imaging to enhance precision during basilar and occipital procedures, reducing risks in complex skull base anatomy.[63] These systems enable frameless stereotaxy for accurate instrument tracking, particularly beneficial in tumor resections near critical neurovascular structures.[64]Comparative anatomy

In mammals

The occipital bone exhibits considerable structural variation across mammalian species, reflecting adaptations to diverse locomotor patterns, feeding strategies, and ecological niches. In general, therian mammals show a conserved basic layout with squamous, lateral, and basal parts, but differences in size, shape, and fusion timing arise due to evolutionary pressures on cranial architecture. For instance, occipital condyle width serves as a reliable predictor of body mass in therian mammals, with larger condyles supporting greater loads in bigger species.[65] In primates, the occipital bone adapts to postural shifts, particularly in the positioning and relative enlargement of the foramen magnum to accommodate upright locomotion. Humans and other bipedal hominins display a more anteriorly positioned and relatively larger foramen magnum compared to quadrupedal monkeys, facilitating a balanced head position atop the vertebral column without excessive neck strain. This adaptation aligns with increased basicranial flexion, which repositions the face beneath the neurocranium for forward-facing posture in bipedal forms.[66][67] Carnivores, such as lions, feature a prominent nuchal crest on the squamous portion of the occipital bone, providing robust attachment sites for powerful neck muscles essential for predation and head manipulation. This crest is highly developed in felids to support forceful bites and grappling, contrasting with less pronounced features in herbivores.[68] Rodents display a reduced squamous portion of the occipital bone, with the interparietal element (part of the squamous region) showing early fusion to the supraoccipital during development, likely as an adaptation to their small body size and rapid growth rates. This early integration contributes to a compact cranium suited for burrowing and agile movements.[69][70] Evolutionary trends in mammals highlight increased basicranial flexion in bipedal lineages, such as hominins, to align the spinal column with the center of gravity and promote a forward head position. This flexion, coupled with encephalization, distinguishes bipedal mammals from quadrupedal relatives, enhancing visual orientation and reducing muscular effort for upright carriage.[67]In non-mammalian vertebrates

In non-mammalian vertebrates, the occipital region's homologues exhibit significant diversity, reflecting evolutionary adaptations to aquatic, terrestrial, and aerial lifestyles, with variations in ossification, fusion, and the presence of a distinct foramen magnum. These structures primarily arise from endochondral ossification of cartilaginous precursors in the chondrocranium, supplemented by dermal bones derived from the exoskeleton in the skull roof, contrasting with the more unified mammalian configuration.[71] In reptiles, the occipital complex consists of separate elements, including the basioccipital and paired exoccipitals as endochondral bones, alongside the supraoccipital, which often incorporates dermal contributions to the skull roof. These bones form a single occipital condyle, typically centered on the basioccipital, enabling articulation with the atlas vertebra in a monocondylic fashion, as seen in lizards (Squamata) where the exoccipitals remain distinct and flank the foramen magnum without extensive fusion in juveniles. This configuration supports robust head mobility while maintaining structural integrity for terrestrial locomotion.[72][73] Birds display a highly derived occipital region adapted for lightweight construction and flight efficiency, with the basioccipital, exoccipitals, and supraoccipital fusing into a compact unit that contributes to the overall cranial lightness. A single occipital condyle persists, but the foramen magnum is notably reduced in size compared to reptiles, minimizing weight while enclosing the brainstem passage. Pneumatic spaces, invaded by diverticula from the tympanic air sacs, often extend into the occipital condyles and surrounding bones, enhancing skeletal aeration as observed in both Mesozoic and modern avian lineages, such as enantiornithines and neornithines. This pneumatization, while variable, underscores the evolutionary emphasis on reducing mass without compromising support for neck muscles.[74][75][76] In fish, particularly teleosts, the occipital homologues are integrated into a more diffuse braincase, with multiple elements such as the basioccipital, exoccipitals, and a prominent dermal supraoccipital forming part of the expansive skull roof. These bones arise from both endochondral and dermal origins, reflecting the primitive osteichthyan condition where the supraoccipital expands dorsally as a dermal plate. Unlike tetrapods, teleosts lack a true, fully enclosed foramen magnum; instead, the occipital region features an open or partially bounded passage for the notochord and spinal cord, accommodating the persistent notochordal structure and flexible cranio-vertebral junction essential for aquatic undulation.[77][78] Amphibians exhibit the most primitive and variable occipital configuration among tetrapods, with cartilaginous precursors in the chondrocranium ossifying late, often post-metamorphosis, leading to incomplete or delayed formation of the basioccipital and supraoccipital. The exoccipitals typically remain separate or show variable fusion with adjacent otic elements, contributing to paired occipital condyles that articulate with the atlas, a plesiomorphic trait retained from early tetrapods. Evolutionarily, these structures trace back to exoskeletal dermal plates that armored the ancestral skull roof, with endochondral components providing basal support, allowing flexibility in semi-aquatic habits while bridging fish-like and reptilian morphologies.[72][71]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/nuchal