Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ondol

View on Wikipedia

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 온돌 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 溫突/溫堗 |

| Revised Romanization | ondol |

| McCune–Reischauer | ondol |

| IPA | [on.dol] |

| Alternate name | |

| Hangul | 구들 |

| Revised Romanization | gudeul |

| McCune–Reischauer | kudŭl |

| IPA | [ku.dɯl] |

Ondol (ON-dol; /ˈɒn.dɒl/,[1] Korean: 온돌; Hanja: 溫突/溫堗; Korean pronunciation: [on.dol]) or gudeul (구들; [ku.dɯl]) in Korean traditional architecture is underfloor heating that uses direct heat transfer from wood smoke to heat the underside of a thick masonry floor. In modern usage, it refers to any type of underfloor heating, or to a hotel or a sleeping room in Korean (as opposed to Western) style.

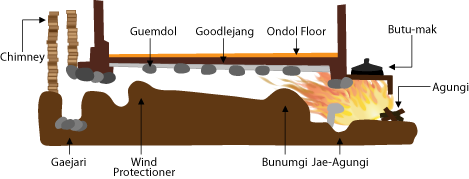

The main components of the traditional ondol are an agungi (아궁이; [a.guŋ.i]), a firebox or stove, accessible from an adjoining room (typically kitchen or master bedroom), a raised masonry floor underlain by horizontal smoke passages, and a vertical, freestanding chimney on the opposite exterior wall providing a draft. The heated floor, supported by stone piers or baffles to distribute the smoke, is covered by stone slabs, clay and an impervious layer such as oiled paper.

History

[edit]Origin

[edit]Use of the ondol has been found at archaeological sites in present-day North Korea. A Neolithic Age archaeological site, circa 5000 BC, discovered in Sonbong, Rason, in present-day North Korea, shows a clear vestige of gudeul in the excavated dwelling (움집).

Early ondols began as gudeul that provided the heating for a home and for cooking. When a fire was lit in the furnace to cook rice for dinner, the flame would extend horizontally because the flue entry was beside the furnace. This arrangement was essential, as it would not allow the smoke to travel upward, which would cause the flame to go out too soon. As the flame would pass through the flue entrance, it would be guided through the network of passages with the smoke. Entire rooms would be built on the furnace flue to create ondol floored rooms.[2]

Etymology

[edit]The term gudeul is a native Korean word. According to Korean folkloric historian Son Jin-tae(孫晋泰) (1900 – missing during the 1950–53 Korean War), gudeul originated from guun-dol (Korean), which means "heated stone", and its pronunciation has changed into gudol or gudul, and again into gudeul.

The term ondol is Sino-Korean and was introduced around the end of the 19th century.[3] Alternate names include janggaeng (장갱; 長坑), hwagaeng (화갱; 火坑), nandol (난돌; 暖突), and yeondol (연돌; 烟突).[4]

Paleolithic to Neolithic Age

[edit]The ruins that are said to have been first discovered using the ondol for a long time include the Hoeryong Odong ruins of Hoeryong in Hoeryong, North Hamgyong Province, North Korea, and the remains of Gulpo Port, which are believed to be a Neolithic residence (house) around 5000 BC in Unggi County, North Hamgyong Province. It is said that there are clear traces of the ondol found there at the time.

The Bronze Age

[edit]Since then, it is estimated that the ondol has been handed down for more than 2,000 years in the Korean Peninsula, considering that it originated from a primitive heating method with a fireplace and a year similar to the method of the Three Kingdoms from the Bronze Age.

The Three Kingdoms period

[edit]The ondol was also painted on the mural of the Goguryeo tomb of Anak No. 3 in Hwanghae-do around the 4th century, which was proof that the ondol was also used in Goguryeo.

Goryeo to Joseon

[edit]From the end of the Goryeo dynasty, the ondol began to appear in the form of canisters made of rooms. It was mainly used by the wealthy and mostly used in rooms for the sick and the elderly. It was considered a luxurious heating system in terms of difficulty in making, management, and fuel consumption.

In the Joseon dynasty, the ondol was used to establish a hierarchical order of seats in the room with the lower neck, a point close to the furnace, as the upper seat. In the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty on May 14, the 17th year of King Taejong's reign (1417), there is a record of making an ondol room for the sick among the students of Seonggyungwan, who were just established at the time. From this, it can be seen that the ondol room was not entirely used. After that, in the 7th year of King Sejong (1425), the ondol of Seonggyungwan was increased to 5 steps, and it was not until the 16th century that all of them became ondol rooms.

In general, all beds were used and wooden floors were used. On February 4, 1563, there was a fire accident in the king's bedroom. Among the explanations of the circumstances at this time, a small ondol structure was made on the king's bed to heat the seat, and at this time, the stone was inadvertently placed incorrectly, and the fire broke out when the fire touched the bed. The article in the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty on March 5, 1624, shows that the Nine's room was also changed to an Ondol room because the Nine's room was not good for the Nine to stay in Panbang, although all the seawalls where the servants of the Four Godfathers lived were ondol during the Gwanghaegun period.

The climate was exceptionally cold, so through the 16th and 17th centuries, which is also called the Little Ice Age, ondol became more and more common, and in the late Joseon dynasty, ondol was widely used in thatched houses of ordinary people.

Current

[edit]Traditional ondol systems provide long-lasting warmth after heating but consume significant fuel, requiring large amounts of firewood. This heavy demand for fuel contributed to deforestation on the Korean Peninsula from the late Joseon Dynasty through the 1950s and 1960s. Starting in the 1960s, firewood was replaced by coal briquettes (yeontan) while retaining the stone slab structure (gudeuljang). However, the incomplete combustion of coal briquettes led to numerous carbon monoxide poisoning incidents. In 1962, to address these issues and improve efficiency, hot-water boilers utilizing the ondol system were developed, reducing both fuel consumption and the risk of poisoning.

Use

[edit]Ondol had traditionally been used as a living space for sitting, eating, sleeping and other pastimes in most Korean homes before the 1960s. Koreans are accustomed to sitting and sleeping on the floor, and working and eating at low tables instead of raised tables with chairs.[5] The furnace burned mainly rice paddy straws, agricultural crop waste, biomass or any kind of dried firewood. For short-term cooking, rice paddy straws or crop waste was preferred, while long hours of cooking and floor heating needed longer-burning firewood. Unlike modern-day water heaters, the fuel was either sporadically or regularly burned (two to five times a day), depending on frequency of cooking and seasonal weather conditions.

With the traditional ondol heating, the floor closer to the furnace was normally warm enough, and the warmest spots reserved for elders and honored guests. Ondol had problems such as environmental pollution and carbon monoxide poisoning resulting from burning coal briquettes.[6] Thus, other technology heats modern Korean homes.

The famous American architect Frank Lloyd Wright was building a hotel in Japan and was invited to a Japanese family's house. The homeowner had experienced the ondol in Korea, and had built an ondol room in his house. Wright reportedly was so impressed [citation needed] that he invented radiant floor heating which uses hot water as the heating medium. Wright introduced floor heating to American houses in the US in the 1930s. [7]

Instead of ondol-hydronic radiant floor heating, modern-day houses such as high-rise apartments have a modernized version of the ondol system. Many architects know the advantages and benefits of ondol, and they are using ondol in modern houses. Since the ondol has been introduced to many countries, it is beginning to be considered as one of the systems of home heating. Modern ondol are not the same as the original version. Almost all Koreans use modern versions, so it is hard to find the traditional ondol system in Korean houses.[8] North Korea still utilizes the basic traditional design of the Ondol that use mostly coal instead of biomass to survive the harsh winters.

-

High exhaust vents jutting sideways

-

Chimney for fumes

-

Chimney

-

Exhaust vents as sideways-oriented pipes

Advantages and disadvantages

[edit]One of the advantages of an ondol is that it can maintain heat for an extended period. In a traditional Korean house, people usually extinguish the fire before going to sleep at night, since it can stay warm until the morning. An ondol conducts heat evenly throughout the whole room, although the part of the room closest to the agungi is much warmer. Comparing the ondol with the Western radiator: the heat from the radiator rises towards the ceiling, but an ondol keeps both the floor and the air in the room warm. The advantage of the ondol is that people do not have to worry about breakdown and repair of the ondol. [citation needed] The Ondol is part of the house, therefore, it is less likely to run into problems. Any combustible materials can be used as fuel for the ondol; there are no special fuel requirements. In contrast to heaters, such as fireplaces or charcoal-based heaters that leave ash in the room, an ondol does not cause pollution in the room leaving it clean and warm.[9][10]

The ondol has some disadvantages. Mud and stones are the main materials that make up the ondol. Such materials take quite a long time to heat up, therefore the room takes a long time to warm up. In addition, it is difficult to adjust the temperature of the room.[9]

Dol bed

[edit]The dol bed, or stone bed, is a manufactured bed that has the same heating effect as ondol. The dol bed industry is estimated to be worth 100 billion South Korean won, comprising 30 to 40 percent of the entire bed industry in South Korea; dol beds are most popular with middle-aged people in their 40s and 50s.[11][12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "ondol". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on September 30, 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "History of Radiant Heating & Cooling Systems" (PDF). Healthyheating.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-12-04. Retrieved 2016-05-19.

- ^ "엠파스 리포트 – 리포트, 논문 자료 한번에 찾자!". Archived from the original on March 7, 2008. Retrieved December 8, 2007.

- ^ "온돌" (in Korean). Doosan Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2019-09-21.

- ^ Donald N., Clark (2000). Culture and Customs of Korea. Greenwood Press. p. 94. ISBN 0313304564.

- ^ "[Korea Encounters] Yeontan briquettes opened windows while warming homes". The Korea Times. 2019-03-12. Retrieved 2023-08-21.

- ^ "Radiant Floor Heating in Theory and Practice" (PDF). ASHRAE Journal. 2002.

- ^ "Traditional Korean Heating System". www.antiquealive.com. Retrieved 2016-04-10.

- ^ a b "All That Korea: Ondol, the very unique Korean heating system". atkorea.blogspot.kr. 26 May 2013. Retrieved 2016-04-10.

- ^ "미디어광장 - 메인". www.hanyang.ac.kr. Retrieved 2016-04-10.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "'스톤 매트리스'로 돌침대 시장 깨운다". 헤럴드경제 미주판 Heraldk.com. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ "[Biz] 돌침대 시장". MK News. Retrieved 22 September 2016.