Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cross-polytope

View on Wikipedia

|

|

| 2 dimensions square |

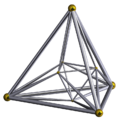

3 dimensions octahedron |

|

|

| 4 dimensions 16-cell |

5 dimensions 5-orthoplex |

In geometry, a cross-polytope,[1] hyperoctahedron, orthoplex,[2] staurotope,[3] or cocube is a regular, convex polytope that exists in n-dimensional Euclidean space. A 2-dimensional cross-polytope is a square, a 3-dimensional cross-polytope is a regular octahedron, and a 4-dimensional cross-polytope is a 16-cell. Its facets are simplexes of the previous dimension, while the cross-polytope's vertex figure is another cross-polytope from the previous dimension.

The vertices of a cross-polytope can be chosen as the unit vectors pointing along each co-ordinate axis – i.e. all the permutations of (±1, 0, 0, ..., 0). The cross-polytope is the convex hull of its vertices. The n-dimensional cross-polytope can also be defined as the closed unit ball (or, according to some authors, its boundary) in the ℓ1-norm on Rn, those points x = (x1, x2..., xn) satisfying

An n-orthoplex can be constructed as a bipyramid with an (n−1)-orthoplex base.

The cross-polytope is the dual polytope of the hypercube. The vertex-edge graph of an n-dimensional cross-polytope is the Turán graph T(2n, n) (also known as a cocktail party graph [4]).

Low-dimensional examples

[edit]In 1 dimension the cross-polytope is a line segment, which can be chosen as the interval [−1, +1].

In 2 dimensions the cross-polytope is a square. If the vertices are chosen as {(±1, 0), (0, ±1)}, the square's sides are at right angles to the axes; in this orientation a square is often called a diamond.

In 3 dimensions the cross-polytope is a regular octahedron—one of the five convex regular polyhedra known as the Platonic solids.

The 4-dimensional cross-polytope also goes by the name hexadecachoron or 16-cell. It is one of the six convex regular 4-polytopes. These 4-polytopes were first described by the Swiss mathematician Ludwig Schläfli in the mid-19th century. The vertices of the 4-dimensional hypercube, or tesseract, can be divided into two sets of eight, the convex hull of each set forming a cross-polytope. Moreover, the polytope known as the 24-cell can be constructed by symmetrically arranging three cross-polytopes.[5]

n dimensions

[edit]The cross-polytope family is one of three regular polytope families, labeled by Coxeter as βn, the other two being the hypercube family, labeled as γn, and the simplex family, labeled as αn. A fourth family, the infinite tessellations of hypercubes, he labeled as δn.[6]

The n-dimensional cross-polytope has 2n vertices, and 2n facets ((n − 1)-dimensional components) all of which are (n − 1)-simplices. The vertex figures are all (n − 1)-cross-polytopes. The Schläfli symbol of the cross-polytope is {3,3,...,3,4}.

The dihedral angle of the n-dimensional cross-polytope is . This gives: δ2 = arccos(0/2) = 90°, δ3 = arccos(−1/3) = 109.47°, δ4 = arccos(−2/4) = 120°, δ5 = arccos(−3/5) = 126.87°, ... δ∞ = arccos(−1) = 180°.

The hypervolume of the n-dimensional cross-polytope is

For each pair of non-opposite vertices, there is an edge joining them. More generally, each set of k + 1 orthogonal vertices corresponds to a distinct k-dimensional component which contains them. The number of k-dimensional components (vertices, edges, faces, ..., facets) in an n-dimensional cross-polytope is thus given by (see binomial coefficient):

The extended f-vector for an n-orthoplex can be computed by (1,2)n, like the coefficients of polynomial products. For example a 16-cell is (1,2)4 = (1,4,4)2 = (1,8,24,32,16).

There are many possible orthographic projections that can show the cross-polytopes as 2-dimensional graphs. Petrie polygon projections map the points into a regular 2n-gon or lower order regular polygons. A second projection takes the 2(n−1)-gon petrie polygon of the lower dimension, seen as a bipyramid, projected down the axis, with 2 vertices mapped into the center.

| n | βn k11 |

Name(s) Graph |

Graph 2n-gon |

Schläfli | Coxeter-Dynkin diagrams |

Vertices | Edges | Faces | Cells | 4-faces | 5-faces | 6-faces |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | β0 | Point 0-orthoplex |

. | ( ) | 1 | |||||||

| 1 | β1 | Line segment 1-orthoplex |

{ } | 2 | 1 | |||||||

| 2 | β2 −111 |

Square 2-orthoplex Bicross |

|

{4} 2{ } = { }+{ } |

4 | 4 | 1 | |||||

| 3 | β3 011 |

Octahedron 3-orthoplex Tricross |

|

{3,4} {31,1} 3{ } |

6 | 12 | 8 | 1 | ||||

| 4 | β4 111 |

16-cell 4-orthoplex Tetracross |

|

{3,3,4} {3,31,1} 4{ } |

8 | 24 | 32 | 16 | 1 | |||

| 5 | β5 211 |

5-orthoplex Pentacross |

|

{33,4} {3,3,31,1} 5{ } |

10 | 40 | 80 | 80 | 32 | 1 | ||

| 6 | β6 311 |

6-orthoplex Hexacross |

|

{34,4} {33,31,1} 6{ } |

12 | 60 | 160 | 240 | 192 | 64 | 1 | |

| ... | ||||||||||||

| n | βn (n−3)11 |

n-orthoplex n-cross |

{3n − 2,4} {3n − 3,31,1} n{} |

2n 0-faces, ... k-faces ..., 2n (n−1)-faces | ||||||||

The vertices of an axis-aligned cross polytope are all at equal distance from each other in the Manhattan distance (L1 norm). Kusner's conjecture states that this set of 2d points is the largest possible equidistant set for this distance.[8]

Generalized orthoplex

[edit]Regular complex polytopes can be defined in complex Hilbert space called generalized orthoplexes (or cross polytopes), βp

n = 2{3}2{3}...2{4}p, or ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ..

..![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() . Real solutions exist with p = 2, i.e. β2

. Real solutions exist with p = 2, i.e. β2

n = βn = 2{3}2{3}...2{4}2 = {3,3,..,4}. For p > 2, they exist in . A p-generalized n-orthoplex has pn vertices. Generalized orthoplexes have regular simplexes (real) as facets.[9] Generalized orthoplexes make complete multipartite graphs, βp

2 make Kp,p for complete bipartite graph, βp

3 make Kp,p,p for complete tripartite graphs βp

n creates Kpn or Turán graphs . An orthogonal projection can be defined that maps all the vertices equally-spaced on a circle, with all pairs of vertices connected, except multiples of n. The regular polygon perimeter in these orthogonal projections is called a petrie polygon.

| p = 2 | p = 3 | p = 4 | p = 5 | p = 6 | p = 7 | p = 8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2{4}2 = {4} = K2,2 |

2{4}3 = K3,3 |

2{4}4 = K4,4 |

2{4}5 = K5,5 |

2{4}6 = K6,6 |

2{4}7 = K7,7 |

2{4}8 = K8,8 | ||

2{3}2{4}2 = {3,4} = K2,2,2 |

2{3}2{4}3 = K3,3,3 |

2{3}2{4}4 = K4,4,4 |

2{3}2{4}5 = K5,5,5 |

2{3}2{4}6 = K6,6,6 |

2{3}2{4}7 = K7,7,7 |

2{3}2{4}8 = K8,8,8 | ||

2{3}2{3}2 {3,3,4} = K2,2,2,2 |

2{3}2{3}2{4}3 K3,3,3,3 |

2{3}2{3}2{4}4 K4,4,4,4 |

2{3}2{3}2{4}5 K5,5,5,5 |

2{3}2{3}2{4}6 K6,6,6,6 |

2{3}2{3}2{4}7 K7,7,7,7 |

2{3}2{3}2{4}8 K8,8,8,8 | ||

2{3}2{3}2{3}2{4}2 {3,3,3,4} = K2,2,2,2,2 |

2{3}2{3}2{3}2{4}3 K3,3,3,3,3 |

2{3}2{3}2{3}2{4}4 K4,4,4,4,4 |

2{3}2{3}2{3}2{4}5 K5,5,5,5,5 |

2{3}2{3}2{3}2{4}6 K6,6,6,6,6 |

2{3}2{3}2{3}2{4}7 K7,7,7,7,7 |

2{3}2{3}2{3}2{4}8 K8,8,8,8,8 | ||

2{3}2{3}2{3}2{3}2{4}2 {3,3,3,3,4} = K2,2,2,2,2,2 |

2{3}2{3}2{3}2{3}2{4}3 K3,3,3,3,3,3 |

2{3}2{3}2{3}2{3}2{4}4 K4,4,4,4,4,4 |

2{3}2{3}2{3}2{3}2{4}5 K5,5,5,5,5,5 |

2{3}2{3}2{3}2{3}2{4}6 K6,6,6,6,6,6 |

2{3}2{3}2{3}2{3}2{4}7 K7,7,7,7,7,7 |

2{3}2{3}2{3}2{3}2{4}8 K8,8,8,8,8,8 |

Related polytope families

[edit]Cross-polytopes can be combined with their dual cubes to form compound polytopes:

- In two dimensions, we obtain the octagrammic star figure {8/2},

- In three dimensions we obtain the compound of cube and octahedron,

- In four dimensions we obtain the compound of tesseract and 16-cell.

See also

[edit]- List of regular polytopes

- Hyperoctahedral group, the symmetry group of the cross-polytope

Citations

[edit]- ^ Coxeter 1973, pp. 121–122, §7.21. illustration Fig 7-2B.

- ^ Conway, J. H.; Sloane, N. J. A. (1991). "The Cell Structures of Certain Lattices". In Hilton, P.; Hirzebruch, F.; Remmert, R. (eds.). Miscellanea Mathematica. Berlin: Springer. pp. 89–90. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-76709-8_5. ISBN 978-3-642-76711-1.

- ^ McMullen, Peter (2020). Geometric Regular Polytopes. Cambridge University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-108-48958-4.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Cocktail Party Graph". MathWorld.

- ^ Bengtsson, Ingemar; Życzkowski, Karol (2017). Geometry of Quantum States: An Introduction to Quantum Entanglement (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-107-02625-4.

- ^ Coxeter 1973, pp. 120–124, §7.2.

- ^ Coxeter 1973, p. 121, §7.2.2..

- ^ Guy, Richard K. (1983), "An olla-podrida of open problems, often oddly posed", American Mathematical Monthly, 90 (3): 196–200, doi:10.2307/2975549, JSTOR 2975549.

- ^ Coxeter, Regular Complex Polytopes, p. 108

References

[edit]- Coxeter, H.S.M. (1973). Regular Polytopes (3rd ed.). New York: Dover.

- pp. 121–122, §7.21, illustration Fig 7.2B

- p. 296, Table I (iii): Regular Polytopes, three regular polytopes in n-dimensions (n≥5)