Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

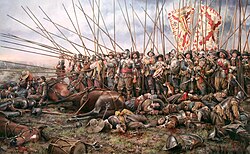

Pike (weapon)

View on Wikipedia

A pike is a long thrusting spear formerly used in European warfare from the Late Middle Ages[1] and most of the early modern period, and wielded by foot soldiers deployed in pike square formation, until it was largely replaced by bayonet-equipped muskets. The pike was particularly well known as the primary weapon of Spanish tercios, Swiss mercenaries, German Landsknecht units and French sans-culottes. A similar weapon, the sarissa, had been used in antiquity by Alexander the Great's Macedonian phalanx infantry.

Design

[edit]

The pike was a long weapon, varying considerably in size, from 3 to 7 m (9.8 to 23.0 ft) long. Generally, a spear becomes a pike when it is too long to be wielded with one hand in combat.[citation needed] It was approximately 2 to 6 kg (4.4 to 13.2 lb) in weight, with the 16th-century military writer Sir John Smythe recommending lighter rather than heavier pikes.[2] It had a wooden shaft with an iron or steel spearhead affixed. The shaft near the head was often reinforced with metal strips called "cheeks" or langets. When the troops of opposing armies both carried the pike, it often grew in a sort of arms race, getting longer in both shaft and head length to give one side's pikemen an edge in combat.[citation needed] The extreme length of such weapons required a strong wood such as well-seasoned ash for the pole, which was tapered towards the point to prevent the pike from sagging on the ends, although drooping or slight flection of the shaft was always a problem in pike handling. It is a common mistake to refer to a bladed polearm as a pike; such weapons are more generally known as halberds, glaives, ranseurs, bills, or voulges.

The great length of the pikes allowed a great concentration of spearheads to be presented to the enemy, with their wielders at a greater distance, but also made pikes unwieldy in close combat. This meant that pikemen had to be equipped with an additional, shorter weapon such as a dagger or sword in order to defend themselves should the fighting degenerate into a melee. In general, however, pikemen attempted to avoid such disorganized combat, in which they were at a disadvantage. To compound their difficulties in a melee, the pikeman often did not have a shield, or had only a small shield which would be of limited use in close-quarters fighting.

Tactics

[edit]

The pike, being unwieldy, was typically used in a deliberate, defensive manner, often alongside other missile and melee weapons. However, better-trained troops were capable of using the pike in an aggressive attack with each rank of pikemen being trained to hold their pikes so that they presented enemy infantry with four or five layers of spearheads bristling from the front of the formation.[citation needed]

As long as it kept good order, such a formation could roll right over enemy infantry, but it did have weaknesses. The men were all moving forward facing in a single direction and could not turn quickly or efficiently to protect the vulnerable flanks or rear of the formation. Nor could they maintain cohesion over uneven ground, as the Scots discovered to their cost at the Battle of Flodden. The huge block of men carrying such unwieldy spears could be difficult to maneuver in any way other than straightforward movement.[citation needed]

As a result, such mobile pike formations sought to have supporting troops protect their flanks or would maneuver to smash the enemy before they could be outflanked themselves. There was also the risk that the formation would become disordered, leading to a confused melee in which pikemen had the vulnerabilities mentioned above.[citation needed]

According to Sir John Smythe, there were two ways for two opposing pike formations to confront one another: cautious or aggressive. The cautious approach involved fencing at the length of the pike, while the aggressive approach involved quickly closing distance, with each of the first five ranks giving a single powerful thrust. In the aggressive approach, the first rank would then immediately resort to swords and daggers if the thrusts from the first five ranks failed to break the opposing pike formation. Smythe considered the cautious approach laughable.[3]

Although primarily a military weapon, the pike could be surprisingly effective in single combat and a number of 16th-century sources explain how it was to be used in a dueling situation; fencers of the time often practiced with and competed against each other with long staves in place of pikes. George Silver considered the 5.5 metres (18 ft) pike one of the more advantageous weapons for single combat in the open, giving it odds over all weapons shorter than 2.4 metres (7.9 ft) or the sword and dagger/shield combination.[4]

History

[edit]Ancient Europe

[edit]

Although very long spears had been used since the dawn of organized warfare (notably illustrated in art showing Sumerian and Minoan warriors and hunters), the earliest recorded use of a pike-like weapon in the tactical method described above involved the Macedonian sarissa, used by the troops of Alexander the Great's father, Philip II of Macedon, and successive dynasties, which dominated warfare for several centuries in many countries.

After the fall of the last successor of Macedon, the pike largely fell out of use for the next 1,000 or so years. The one exception to this appears to have been in Germany, where Tacitus recorded Germanic tribesmen in the 2nd century AD as using "over-long spears". He consistently refers to the spears used by the Germans as being "massive" and "very long" suggesting that he is describing in essence a pike. Julius Caesar, in his De Bello Gallico, describes the Helvetii as fighting in a tight, phalanx-like formation with spears jutting out over their shields. Caesar was probably describing an early form of the shieldwall so popular in later times.

Medieval Europe revival

[edit]In the Middle Ages, the principal users of the pike were urban militia troops such as the Flemings or the peasant array of the lowland Scots. For example, the Scots used a spear formation known as the schiltron in several battles during the Wars of Scottish Independence including the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, and the Flemings used their geldon long spear to absorb the attack of French knights at the Battle of the Golden Spurs in 1302, before other troops in the Flemish formation counterattacked the stalled knights with goedendags. Both battles were seen by contemporaries as stunning victories of commoners over superbly equipped, mounted, military professionals, where victory was owed to the use of the pike and the brave resistance of the commoners who wielded them.

These formations were essentially immune to the attacks of mounted men-at-arms as long as the knights obligingly threw themselves on the spear wall and the foot soldiers remained steady under the morale challenge of facing a cavalry charge, but the closely packed nature of pike formations rendered them vulnerable to enemy archers and crossbowmen who could shoot them down with impunity, especially when the pikemen did not have adequate armor. Many defeats, such as at Roosebeke and Halidon Hill, were suffered by the militia pike armies when faced by cunning foes who employed their archers and crossbowmen to thin the ranks of the pike blocks before charging in with their (often dismounted) men-at-arms.

Medieval pike formations tended to have better success when they operated in an aggressive fashion. The Scots at the Battle of Stirling Bridge (1297), for example, utilized the momentum of their charge to overrun an English army while the Englishmen were crossing a narrow bridge. At the Battle of Laupen (1339), Bernese pikemen overwhelmed the infantry forces of the opposing Habsburg/Burgundian army with a massive charge before wheeling over to strike and rout the Austro-Burgundian horsemen as well. At the same time however such aggressive action required considerable tactical cohesiveness or suitable terrain to protect the vulnerable flanks of the pike formations especially from the attack of mounted man-at-arms.[citation needed] When these features were not available, militia often suffered costly failures,[clarification needed] such as at the battles of Mons-en-Pevele (1304), Cassel (1328), Roosebeke (1382) and Othee (1408).[citation needed] The constant success of the Swiss mercenaries in the later period was attributed to their extreme discipline and tactical unity due to semi-professional nature, allowing a pike block to somewhat alleviate the threat presented by flanking attacks.

Perhaps copying the nearby Swiss model, the pike had a certain diffusion also in the duchy of Milan in the last two years of the 14th century. In 1391, a decree by Gian Galeazzo Visconti ordered the pikes to be at least 10 feet long in Milan, equivalent to 4.35 m (14.3 ft) and their tips to be reinforced with iron strips to prevent enemies, given their length, from cutting or breaking them. A second decree of 1397 provided that half the infantry of the duchy were armed with pikes.[5]

It was not uncommon for aggressive pike formations to be composed of dismounted men-at-arms, as at the Battle of Sempach (1386), where the dismounted Austrian vanguard, using their lances as pikes, had some initial success against their predominantly halberd-equipped Swiss adversaries. Dismounted Italian men-at-arms also used the same method to defeat the Swiss at the Battle of Arbedo (1422). Equally, well-armored Scottish nobles (accompanied even by King James IV) were recorded as forming the leading ranks of Scottish pike blocks at the Battle of Flodden (1513), incidentally rendering the whole formation resistant to English archery.

Renaissance Europe heyday

[edit]

The Swiss solved the pike's earlier problems and brought a renaissance to pike warfare in the 15th century, establishing strong training regimens to ensure they were masters of handling the Spiess (the German term for "skewer") on maneuvers and in combat; they also introduced marching to drums for this purpose. This meant that the pike blocks could rise to the attack, making them less passive and more aggressive formations, but sufficiently well trained that they could go on the defensive when attacked by cavalry. German soldiers known as Landsknechts later adopted Swiss methods of pike handling.

The Scots predominantly used shorter spears in their schiltron formation; their attempt to adopt the longer Continental pike was dropped for general use after its ineffective use led to humiliating defeat at the Battle of Flodden.

Such Swiss and Landsknecht phalanxes also contained men armed with two-handed swords, or Zweihänder, and halberdiers for close combat against both infantry and attacking cavalry.

The Swiss were confronted with the German Landsknecht who used similar tactics as the Swiss, but more pikes in the more difficult German thrust (German: deutscher Stoß: holding a pike that had its weight in the lower 1/3 at the end with two hands), which was utilized in a more flexible attacking column.

The high military reputation of the Swiss and the Landsknechts again led to the employment of mercenary units across Europe in order to train other armies in their tactics. These two, and others who had adopted their tactics, faced off in several wars, leading to a series of developments as a result.[6]

These formations had great successes on the battlefield, starting with the astonishing victories of the Swiss cantons against Charles the Bold of Burgundy in the Burgundian Wars, in which the Swiss participated in 1476 and 1477. In the Battles of Grandson, Morat, and Nancy, the Swiss not only successfully resisted the attacks of enemy knights, as the relatively passive Scottish and Flemish infantry squares had done in the earlier Middle Ages, but also marched to the attack with great speed and in good formation, their attack columns steamrolling the Burgundian forces, sometimes with great massacre.

The deep pike attack column remained the primary form of effective infantry combat for the next forty years, and the Swabian War saw the first conflict in which both sides had large formations of well-trained pikemen. After that war, its combatants—the Swiss (thereafter generally serving as mercenaries) and their Landsknecht imitators—would often face each other again in the Italian Wars, which would become in many ways the military proving ground of the Renaissance.

The so-called Schefflin was a polearm, closely related to the pike, which from the late 1400s and throughout the 16th century saw widespread use in the German-speaking world. It served as a multipurpose weapon for both infantry (in the manner of pikes) and light cavalry (in the manner of demi-lances). Characteristically, it featured a large, hollow-made and leaf-shaped head of about 50 cm (1.6 ft) or more, which was attached to a long and slender shaft. Apart from being used by soldiers in battle, a tassel fixed to the socket of the head together with optional further embellishment made the Schefflin an appropriate main weapon for princely bodyguards and courtly officials. There seems to be a close relation between the contemporary German term Schefflin and the West European terms javeline (French) and javelin (English), both referring to some type of cavalry spear. Although rarely noticed, many of these weapons have survived to this day. Some pieces, of which many are said to have been used by the personal entourage of Henry VIII, are kept at the Royal Armouries in Leeds.

Ancient China

[edit]Pikes and long halberds were in use in ancient China from the Warring States period since the 5th century BC. Infantrymen used a variety of long polearm weapons, but the most popular was the dagger-axe, pike-like long spear, and the ji. The dagger-axe and ji came in various lengths, from 2.75 to 5.5 m (9.0 to 18.0 ft); the weapon consisted of a thrusting spear with a slashing blade appended to it. Dagger-axes and ji were an extremely popular weapon in various kingdoms, especially for the Qin state and Qin dynasty, and possibly the succeeding Han dynasty, who produced 5.5 m (18 ft) halberd and pike-like weapons, as well as 6.7 m (22 ft) long pikes during the war against Xiongnu.[7]

Classical Japan

[edit]During the continuous European development of the pike, Japan experienced a parallel evolution of pole weapons.

In Classical Japan, the Japanese style of warfare was generally fast-moving and aggressive, with far shallower formations than their European equivalents. The naginata and yari were more commonly used than swords for Japanese ashigaru foot soldiers and dismounted samurai due to their greater reach. Naginata, first used around 750 AD, had curved sword-like blades on wooden shafts with often spiked metal counterweights. They were typically used with a slashing action and forced the introduction of shin guards as cavalry battles became more important. Yari were spears of varying lengths; their straight blades usually had sharpened edges or protrusions from the central blade, and were fitted to a hollowed shaft with an extremely long tang.

Medieval Japan

[edit]During the later half of the 16th century in Medieval Japan, pikes used were generally 4.5 to 6.5 m (15 to 21 ft) long, but sometimes up to 10 m (33 ft) in length. By this point, pikemen were becoming the main forces in armies. They formed lines, combined with arquebusiers and spearmen. Formations were generally only two or three rows deep.

Pike and shot

[edit]

In the aftermath of the Italian Wars, from the late 15th century to the late 16th century, most European armies adopted the use of the pike, often in conjunction with primitive firearms such as the arquebus and caliver, to form large pike and shot formations.[citation needed]

The quintessential example of this development was the Spanish tercio, which consisted of a large square of pikemen with small, mobile squadrons of arquebusiers moving along its perimeter, as well as traditional men-at-arms. These three elements formed a mutually supportive combination of tactical roles: the arquebusiers harried the enemy line, the pikemen protected the arquebusiers from enemy cavalry charges, and the men-at-arms, typically armed with swords and javelins, fought off enemy pikemen when two opposing squares made contact. The Tercio deployed smaller numbers of pikemen than the huge Swiss and Landsknecht columns, and their formation ultimately proved to be much more flexible on the battlefield.[citation needed]

Mixed formations of men quickly became the norm for European infantrymen, with many, but not all, seeking to imitate the Tercio; in England, a combination of billmen, longbowmen, and men-at-arms remained the norm, though this changed when the supply of yew on the island dwindled.[citation needed]

The percentage of men who were armed with firearms in Tercio-like formations steadily increased as firearms advanced in technology. This advance is believed to be the demise of cavalry when in fact it revived it. From the late 16th century and into the 17th century, smaller pike formations were used, invariably defending attached musketeers, often as a central block with two sub-units of shooters, called "sleeves of shot", on either side of the pikes. Although the cheaper and versatile infantry increasingly adopted firearms, cavalry's proportion in the army remained high.[citation needed]

During the English Civil War (1642–1651) the New Model Army (1646–1660) initially had two musketeers for each pikeman.[8] Two musketeers for each pikeman was not the agreed mix used throughout Europe, and when in 1658, Oliver Cromwell, by then the Lord Protector, sent a contingent of the New Model Army to Flanders to support his French allies under the terms of their treaty of friendship (the Treaty of Paris, 1657) he supplied regiments with equal numbers of musketeers and pikemen.[9]} On the battlefield, the musketeers lacked protection against enemy cavalry, and the two types of foot soldier supported each other.

The post Restoration English Army used pikemen and by 1697 (the last year of the Nine Years' War) English infantry battalions fighting in the Low Countries still had two musketeers to every pikemen and fought in the now traditional style of pikemen five ranks deep in the centre, with six ranks of musketeers on each side.[10]

According to John Kersey in 1706, the pike was typically 4.3 to 4.9 m (14 to 16 ft) in length.[11]

End of the pike era

[edit]

The mid-17th century to the early 18th century saw the decline of the pike in most European armies. This started with the proliferation of the flintlock musket, which gave the musketeer a faster rate of fire than he before possessed, incentivizing a higher ratio of shot to pikes on the battlefield. It continued with development of the plug bayonet, followed by the socket bayonet in the 1680s and 1690s. The plug bayonet did not replace the pike as it required a soldier surrender his ability to shoot or reload to fix it, but the socket bayonet solved that issue. The bayonet added a long blade of up to 60 cm (24 in) to the end of the musket, allowing the musket to act as a spear-like weapon when held out with both hands. Although they did not have the full reach of pikes, bayonets were effective against cavalry charges, which used to be the main weakness of musketeer formations, and allowed armies to massively expand their potential firepower by giving every infantryman a firearm; pikemen were no longer needed to protect musketeers from cavalry. Furthermore, improvements in artillery caused most European armies to abandon large formations in favor of multiple staggered lines, both to minimize casualties and to present a larger frontage for volley fire. Thick hedges of bayonets proved to be an effective anti-cavalry solution, and improved musket firepower was now so deadly that combat was often decided by shooting alone.

A common end date for the use of the pike in most infantry formations is 1700, such as the Prussian and Austrian armies. Others, including the Swedish and Russian armies, continued to use the pike as an effective weapon for several more decades, until the 1720s and 1730s (the Swedes of King Charles XII in particular using it to great effect until 1721). At the start of the Great Northern War in 1700, Russian line infantry companies had 5 NCOs, 84 musketeers, and 18 pikemen, the musketeers initially being equipped with sword-like plug bayonets; they did not fully switch to socket bayonets until 1709. A Swedish company consisted of 82 musketeers, 48 pikemen, and 16 grenadiers.[12] The Army of the Holy Roman Empire maintained a ratio of 2 muskets to 1 pike in the middle to late 17th century, officially abandoning the pike in 1699. The French, meanwhile, had a ratio of 3-4 muskets to 1 pike by 1689.[13] Both sides of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in the 1640s and 1650s preferred a ratio of 2 muskets to 1 pike, but this was not always possible.[14]

During the American Revolution (1775–1783), pikes called "trench spears" made by local blacksmiths saw limited use until enough bayonets could be procured for general use by both Continental Army and attached militia units.

Throughout the Napoleonic era, the spontoon, a type of shortened pike that typically had a pair of blades or lugs mounted to the head, was retained as a symbol by some NCOs; in practice it was probably more useful for gesturing and signaling than as a weapon for combat.

As late as Poland's Kościuszko Uprising in 1794, the pike reappeared as a child of necessity which became, for a short period, a surprisingly effective weapon on the battlefield. In this case, General Thaddeus Kosciuszko, facing a shortage of firearms and bayonets to arm landless serf partisans recruited straight from the wheat fields, had their sickles and scythes heated and straightened out into something resembling crude "war scythes". These weaponized agricultural accouterments were then used in battle as both cutting weapons, as well as makeshift pikes. The peasant "pikemen" armed with these crude instruments played a pivotal role in securing a near impossible victory against a far larger and better equipped Russian army at the Battle of Racławice, which took place on 4 April 1794.

Civilian pikeman played a similar role, though outnumbered and outgunned, in the 1798 rising in Ireland four years later. Here, especially in the Wexford Rebellion and in Dublin, the pike was useful mainly as a weapon by men and women fighting on foot against cavalry armed with guns.

Improvised pikes, made from bayonets on poles, were used by escaped convicts during the Castle Hill rebellion of 1804.

As late as the Napoleonic Wars, at the beginning of the 19th century, even the Russian militia (mostly landless peasants, like the Polish partisans before them) could be found carrying shortened pikes into battle. As the 19th century progressed, the obsolete pike would still find a use in such countries as Ireland, Russia, China, and Australia, generally in the hands of desperate peasant rebels who did not have access to firearms. John Brown purchased a large number of pikes and brought them to his raid on Harpers Ferry.

One attempt to resurrect the pike as a primary infantry weapon occurred during the American Civil War (1861–1865) when the Confederate States of America planned to recruit twenty regiments of pikemen in 1862. In April 1862 it was authorised that every Confederate infantry regiment would include two companies of pikemen, a plan supported by Robert E. Lee. Many pikes were produced but were never used in battle and the plan to include pikemen in the army was abandoned.[citation needed]

Shorter versions of pikes called boarding pikes were also used on warships—typically to repel boarding parties, up to the late 19th century.

The great Hawaiian warrior king Kamehameha I had an elite force of men armed with very long spears who seem to have fought in a manner identical to European pikemen, despite the usual conception of his people's general disposition for individualistic dueling as their method of close combat. It is not known whether Kamehameha himself introduced this tactic or if it was taken from the use of traditional Hawaiian weapons.[citation needed]

The pike was issued as a British Home Guard weapon in 1942 after the War Office acted on a letter from Winston Churchill saying "every man must have a weapon of some kind, be it only a mace or pike". However, these hand-held weapons never left the stores after the pikes had "generated an almost universal feeling of anger and disgust from the ranks of the Home Guard, demoralised the men and led to questions being asked in both Houses of Parliament".[15] The pikes, made from obsolete Lee–Enfield rifle bayonet blades welded to a steel tube, took the name of "Croft's Pikes" after Henry Page Croft, the Under-Secretary of State for War who attempted to defend the fiasco by stating that they were a "silent and effective weapon".[16]

In Spain, beginning in 1715 and ending in 1977, there were night patrol guards in cities called serenos who carried a short pike of 1.5 m (4.9 ft) called chuzo.

Pikes live on today only in ceremonial roles, being used to carry the colours of an infantry regiment and with the Company of Pikemen and Musketeers of the Honourable Artillery Company, or by some of the infantry units on duty during their rotation as guard[17] for the President of the Italian Republic at the Quirinal Palace in Rome, Italy.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Verbruggen, J.F. (1997). The Art of Warfare in the Western Europe during the Middle Ages. Translated by Willard, S.; Southern, R.W. Boydell & Brewer. p. 151.

- ^ "Everything you ever wanted to know about Pikes but were afraid to ask..." Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ^ "On the Push of Pike". Art Military. 21 October 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ Silver, George (1599). "Paradoxes of Defense". Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ^ Romanoni, Fabio (2023). "Balestrieri, pavesari e lance lunghe: la tripartizione funzionale delle cernite di Gian Galeazzo Visconti del 1397". "Castrum paene in mundo singulare". Scritti per Aldo Settia in occasione del novantesimo compleanno (in Italian). Genova: Sagep Editori. pp. 214–216. ISBN 979-12-5590-015-3. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

- ^ Schaufelberger, Walter (1987). Der alte Schweizer und sein Krieg (in German). Frauenfeld: Huber. ISBN 978-3-7193-0980-0.

- ^ An Army Reborn (Terracotta Army) Documentary Video (August 12, 2017)

- ^ Firth, C.H. (1972) [1902]. Cromwell's Army – A history of the English soldier during the civil wars, the Commonwealth and the Protectorate (1st ed.). London: Methuen & Co Ltd. p. 70.

- ^ Firth, C.H. (1898). "Royalist and Cromwellian 76Armies in Flanders, 1657–1662". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. pp. 76–77.

- ^ Chandler, David G.; Beckett, Ian Frederick William (2003). The Oxford History of the British Army. Oxford University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-19-280311-5.

- ^ Phillips, Edward (1706). Kersey, John (ed.). The New World of Words; or, universal English dictionary (6th ed.). London: J. Phillips.

- ^ Gabriele Esposito. "Armies of the Great Northern War: 1700-1720". Osprey: 2019. Pages 10 and 16.

- ^ Guthrie, William. "The Later Thirty Years War: From the Battle of Wittstock to the Treaty of Westphalia". Praeger, February 2003. Page 33.

- ^ Reid, Stuart. "All The King's Armies: A Military History of the English Civil War: 1642-1651". Spellmount, July 2007. Chapter 1.

- ^ "Home Guard Pike". home-guard.org.uk. 7 September 1998. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ MacKenzie, S.P. (1995). The Home Guard: A Military and Political History. Oxford University Press. pp. 97–100. ISBN 0-19-820577-5.

- ^ Cambio della guardia al Quirinale – Infantry Passing out Parade 8:41. via YouTube.

Further reading

[edit]- Delbrück, Hans. History of the Art of War, originally published in 1920; University of Nebraska Press (reprint), 1990 (trans. J. Renfroe Walter). Volume III: Medieval Warfare.

- Fegley, Randall. The Golden Spurs of Kortrijk: How the Knights of France Fell to the Foot Soldiers of Flanders in 1302, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2002.

- McPeak, William. Military Heritage, 7(1), August 2005, pp. 10,12,13.

- Oman, Charles. A History of the Art of War in the Sixteenth Century. London: Methuen & Co., 1937.

- Parker, Geoffrey. The Military Revolution: Military Innovation and the Rise of the West 1500–1800, Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Smith, Goldwyn. Irish History and the Irish Question, New York: McClure, Phillips & Co., 1905.

- Vullaimy, C. E. Royal George: A Study of King George III, His Experiment in Monarchy, His Decline and Retirement, D. Appleton-Century Company, Inc., 1937.

External links

[edit] Media related to Pikes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pikes at Wikimedia Commons