Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Swiss Guard

View on Wikipedia| Pontifical Swiss Guard | |

|---|---|

| Pontificia Cohors Helvetica (Latin) Guardia Svizzera Pontificia (Italian) Päpstliche Schweizergarde (German) Garde suisse pontificale (French) Guardia svizra papala (Romansh) | |

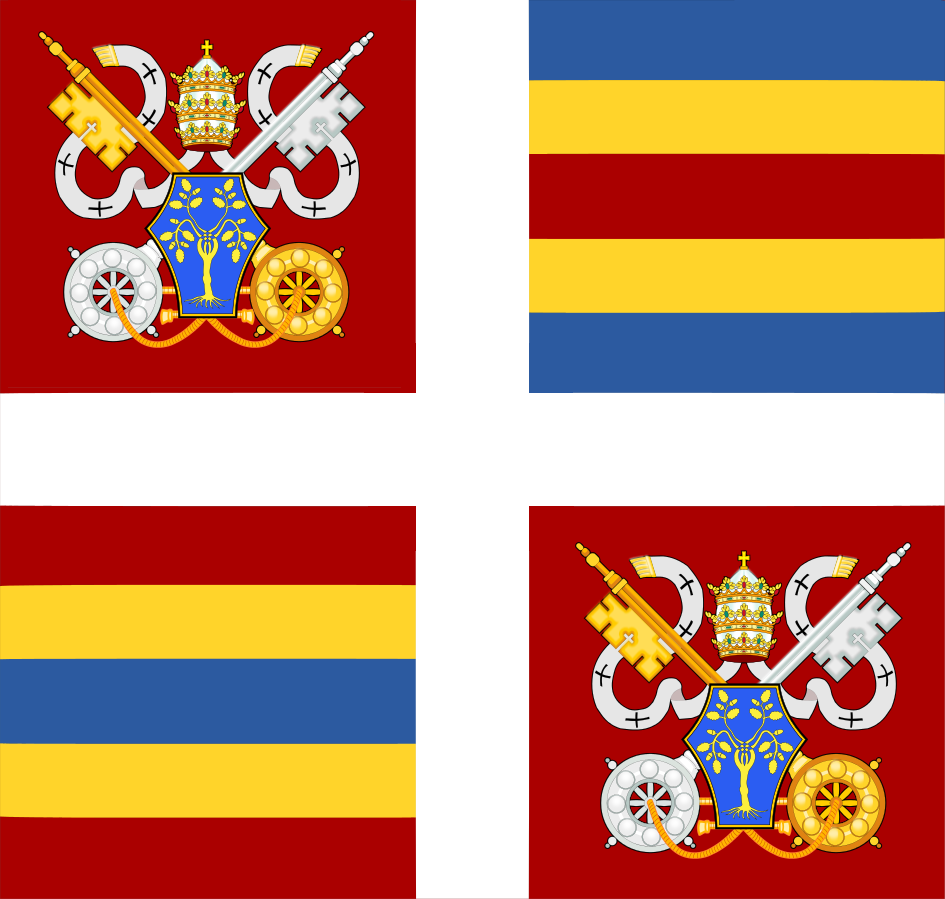

The generic banner of the Pontifical Swiss Guard | |

| Active | 1506–1527 1548–1798 1800–1809 1814–present[1] |

| Country |

|

| Allegiance | The Pope |

| Type | Guard of honour Protective security unit |

| Role | Bodyguard Public duties |

| Size | 135 men |

| Garrison/HQ | Vatican City |

| Patron | |

| Mottos | Acriter et Fideliter "Fiercely and Faithfully" |

| Colors | Red, yellow & blue |

| Anniversaries | 6 May[1] |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Commander-in-chief | Pope Leo XIV |

| Commander | Colonel Christoph Graf |

| Vice commander | Lt Colonel Loïc Marc Rossier |

The Pontifical Swiss Guard,[note 1] also known as the Papal Swiss Guard or simply Swiss Guard,[3] is an armed forces, guard of honour, and protective security unit, maintained by the Holy See to protect the Pope and the Apostolic Palace within the territory of the Vatican City State. Established in 1506 under Pope Julius II, it is among the oldest military units in continuous operation[4] and is sometimes called "the world's smallest army".[3]

The Swiss Guard is recognised by its Renaissance-era dress uniform, consisting of a tunic striped in red, dark blue, and yellow; high plumed helmet; and traditional weapons such as the halberd. Guardsmen perform their protective duties in functional attire and with modern firearms. Since the assassination attempt on Pope John Paul II in 1981, the Guard has placed greater emphasis on its nonceremonial roles and has sought more training in anti-irregular military counterintelligence, commando-style raids, counter-sniper tactics, counterterrorism, close-quarters battle, defusing and disposal of bombs, executive protection, hostage rescue, human intelligence, medical evacuation, reconnaissance, tactical driving, tactical medical services, and tactical fast shooting by small arms.

The Swiss Guard is considered an elite military unit. It is highly selective in its recruitment: candidates must be unmarried Swiss Catholic males between 19 and 30 years of age and at least 5 feet 8.5 inches (1.74 meters), who have completed basic training with the Swiss Armed Forces and hold a professional diploma or high school degree.[5][6] As of 2024, there were 135 members.[7]

The Swiss Guard's security mission extends to the Pope's apostolic travels, the pontifical palace of Castel Gandolfo, and the College of Cardinals when the papal throne is vacant. Though the Guard serve as watchmen of Vatican City, the overall security and law enforcement of the city-state is conducted by the Corps of Gendarmerie of Vatican City, which is a separate body.

History

[edit]Italian Wars

[edit]

The Pontifical Swiss Guard has its origins in the 15th century. Pope Sixtus IV (1471–1484) had allied with the Swiss Confederacy and built barracks in Via Pellegrino after foreseeing the possibility of recruiting Swiss mercenaries. The pact was renewed by Pope Innocent VIII (1484–1492) in order to use Swiss troops against the Duke of Milan. Alexander VI (1492–1503) later used the Swiss mercenaries during his alliance with the King of France.

During the time of the Borgias, the Italian Wars began, in which the Swiss mercenaries were a fixture on the front lines among the warring factions, sometimes for France, and sometimes for the Holy See or the Holy Roman Empire. The mercenaries enlisted when they heard King Charles VIII of France was going to war with Naples. Among the participants in the war against Naples was Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, the future Pope Julius II (1503–1513), who was well acquainted with the Swiss, having been Bishop of Lausanne years earlier.[citation needed]

The expedition failed, in part thanks to new alliances made by Alexander VI against the French. When Cardinal della Rovere became Pope Julius II in 1503, he asked the Swiss Diet to provide him with a constant corps of 200 Swiss mercenaries. This was made possible through financing by German merchants from Augsburg, Ulrich, and Jacob Fugger, who had invested in the Pope and saw fit to protect their investment.[8]

In September 1505, the first contingent of 150 soldiers departed on foot to Rome, under the command of Kaspar von Silenen. They entered the city on 22 January 1506, now regarded as the official date of the Guard's foundation.[9][10]

"The Swiss see the sad situation of the Church of God, Mother of Christianity, and realize how grave and dangerous it is that any tyrant, avid for wealth, can assault with impunity, the common Mother of Christianity," declared the Swiss theologian Huldrych Zwingli, who later became a Protestant reformer. Pope Julius II later granted the Guard the title "Defenders of the Church's freedom".[11]

The force has varied greatly in size over the years and on occasion has been disbanded and reconstituted.

Its most significant hostile engagement came on 6 May 1527 during the Sack of Rome. As troops of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V advanced, 147 of the 189 Guards, including their commander Caspar Röist, died fighting to allow Clement VII to escape through the Passetto di Borgo, escorted by the other 42 guards. The last-stand battlefield is located on the southern side of St. Peter's Basilica, close to the Campo Santo Teutonico (German Graveyard).[12]

Clement VII was forced to replace the depleted Swiss Guard with a contingent of 200 German mercenaries (Custodia Peditum Germanorum).[12]

In 1537, Pope Paul III ordered the Swiss Guard to be reinstated and sent Cardinal Ennio Filonardi to oversee recruitment. Anti-papal sentiment in Switzerland hindered recruitment. In 1548, the papacy reached an agreement with the mayor of Lucerne, Nikolaus von Meggen, to swear-in 150 new Swiss Guardsmen under commander Jost von Meggen, the mayor's nephew.[12]

Early modern history

[edit]

After the end of the Italian Wars, the Swiss Guard ceased to be used as a military combat unit in the service of the Pope and its role became mostly that of the protection of the person of the Pope and of an honour guard. However, twelve members of the Pontifical Swiss Guard of Pius V served as part of the Swiss Guard of admiral Marcantonio Colonna at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571.[13]

The office of commander of the Papal Guard came to be a special honour in the Catholic region of the Swiss Confederacy. It became strongly associated with the leading family of Lucerne, Pfyffer von Altishofen, a family which between 1652 and 1847 provided nine out of ten of the commanders. The exception was Johann Kaspar Mayr von Baldegg, of Lucerne, who served 1696–1704.[14]

In 1798, commander Franz Alois Pfyffer von Altishofen went into exile with the deposed Pius VI. After the death of the Pope on 29 August 1799, the Swiss Guard was disbanded and then reinstated by Pius VII in 1800. In 1809, Rome was again captured by the French and the guard was again disbanded.[1] Pius VII was exiled to Fontainebleau. The guard was reinstated in 1814,[1] when the Pope returned from exile, under the previous commander Karl Leodegar Pfyffer von Altishofen.[citation needed]

Modern history

[edit]

The guard was disbanded in 1848, when Pius IX fled to Gaeta. In 1849, it was reinstated when the Pope returned to Rome.

After the Piedmontese invasion of Rome, the Swiss Guard declined in the later 19th century into a purely ceremonial body with low standards. Guards on duty at the Vatican were "Swiss" only in name, mostly born in Rome to parents of Swiss descent and speaking the Roman dialect. The guards were trained solely for ceremonial parade, kept only a few obsolete rifles in store and wore civilian dress when drilling or in barracks. Administration, accommodation, discipline and organization were neglected and the unit numbered only about 90 men out of an authorized establishment of 133.[15]

The modern Swiss Guard is the product of the reforms pursued by Jules Repond, commander during the years 1910–1921. Repond proposed recruiting only native citizens of Switzerland, and he introduced rigorous military exercises. He attempted to introduce modern arms, but Pius X permitted the presence of firearms only if they were not functional. Repond's reforms and strict discipline were not well received by the corps, culminating in a week of open mutiny in July 1913, and the subsequent dismissal of thirteen ringleaders from the guard.[16]

In his project to restore the Swiss Guard to its former prestige, Repond dedicated himself to the study of historical costume, with the aim of designing a new uniform that would be both reflective of the historical Swiss costume of the 16th century and suited for military exercise. The result of his studies was published in 1917 as Le costume de la Garde suisse pontificale et la Renaissance italienne. Repond designed the distinctive Renaissance-style uniforms worn by the modern Swiss Guard. The introduction of the new uniforms was completed in May 1914.

In 1929, the foundation of Vatican City as a modern sovereign state was effected by the Lateran Treaty, negotiated between the Holy See and Italy. The duties of protecting public order and security in the Vatican lay with the Papal Gendarmerie Corps, while the Swiss Guard, the Palatine Guard and the Noble Guard served mostly ceremonial functions.[17]

In 1970, the Palatine and Noble Guards were disbanded by Paul VI, leaving the Swiss Guard as the only ceremonial guard unit of the Vatican. At the same time, the Gendarmerie Corps was transformed into a central security office, with the duties of protecting the Pope, defending Vatican City, and providing police and security services within its territory, while the Swiss Guard continued to serve ceremonial functions only. In June 1976, Paul VI in a decree defined the nominal size of the corps at 90 men. In April 1979, this was increased to 100 men by John Paul II . As of 2010 the guard numbered 107 halberdiers, divided into three squads, with commissioned and non-commissioned officers.[17]

Since the assassination attempt on John Paul II of 13 May 1981, a much stronger emphasis has been placed on the guard's non-ceremonial roles.[18] The Swiss Guard has developed into a modern guard corps equipped with modern small arms. Members of the Swiss Guard in plain clothes now accompany the Pope on his travels abroad for his protection.

On 4 May 1998 commander Alois Estermann was murdered on the day of his promotion. Estermann and his wife, Gladys Meza Romero, were killed by the young guardsman Cédric Tornay, who later committed suicide. The case received considerable public attention and became the subject of a number of conspiracy theories alleging Cold War politics or involvement by the Opus Dei prelature. British journalist John Follain, who published a book on the case in 2006, concluded that the killer acted purely out of personal motives.[19]

In 2002, the first non-white Swiss Guard joined the militia.[20][21]

In April–May 2006, on the occasion of the 500th anniversary of the Swiss Guard, 80 former guardsmen marched from Bellinzona in southern Switzerland to Rome, recalling the march of the original 200 Swiss guards to take up Papal service in 1505. The march had been preceded by other celebrations in Lucerne, including a rally of veterans of the Guard and a Mass.[22] In a public ceremony on 6 May 2006, 33 new guards were sworn in on the steps of St. Peter's Basilica, instead of the traditional venue in the San Damaso Courtyard. The date chosen marked the anniversary of the Sack of Rome when the Swiss Guard was nearly destroyed. Present at this event were representatives of the Company of Pikemen and Musketeers of the Honourable Artillery Company of London and the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts.

In December 2014, Pope Francis directed that Daniel Anrig's term as commander should end on 31 January 2015, and that he be succeeded by his deputy Christoph Graf. This followed reports about Anrig's "authoritarian style".[23]

In 2015, with the rise of Islamic terrorism in Europe and open threats against the Vatican issued by the Islamic State (ISIS), Vatican officials collaborated with Italian authorities to improve the protection of Vatican City against attacks that cannot be reasonably defended against by the Swiss Guard and Vatican Gendarmerie, notably against drone attacks.[24]

In October 2019, the Swiss Guard was expanded to 135 men.[25][26] Previously, according to article 7 of the regulations,[which?] the Swiss Guard was made up of 110 men.

-

A member of the Swiss Guard during the reign of Pius VII, c. 1811, by Hortense Haudebourt-Lescot

-

Kneeling salute in Clementine Hall, 1937

-

Marching in exercise uniform with Gewehr 98 rifles, 1938

-

A member of the Pontifical Swiss Guard with halberd, 2011

Recruitment and service

[edit]

Recruits to the guards must be Catholic, single males with Swiss citizenship who have completed high school at least, basic training with the Swiss Armed Forces, and of irreproachable reputation and health. Recruits must be between 19 and 30 years of age, at least 174 cm (5 ft 8.5 in) tall, and prepared to sign up for at least 26 months.[5][6] In 2009, Pontifical Swiss Guard commandant Daniel Anrig suggested that the Guard might be open to recruiting women far in the future.[27] Guards are permitted to marry after five years of service.[28]

Qualified candidates must apply to serve. Those who are accepted serve for a minimum of 26 months.[5] Regular guardsmen (halberdiers) were paid a tax-free salary of €1,300 per month plus overtime in 2006. They also receive Vatican citizenship for the duration of their service.[29] Accommodation and board are provided.[30] Members of the guard are eligible for pontifical decorations. The Benemerenti medal is usually awarded after three years of faithful service.

Oath ceremony on 6 May

[edit]If accepted, new guards are sworn in every year on 6 May, the anniversary of the Sack of Rome, in the San Damaso Courtyard (Italian: Cortile di San Damaso) in the Vatican. In 2025, the ceremony was postponed following the death of Pope Francis on 11 April and the announcement that the conclave to elect his successor would be held in early May. The ceremony was eventually held on 4 October, and was also unusual in having the Pope himself present.[31]

At the ceremony, the chaplain of the guard reads aloud the full oath of allegiance in the command languages of the Guard (German, Italian, and French):[32][33]

(English translation) I swear that I will faithfully, loyally and honourably serve the Supreme Pontiff (name of Pope) and his legitimate successors, and dedicate myself to them with all my strength, sacrificing, if necessary, my life to defend them. I assume this same commitment with regard to the Sacred College of Cardinals whenever the Apostolic See is vacant. Furthermore, I promise the Captain Commandant and my other superiors respect, fidelity and obedience. I swear to observe all that the honour of my position demands of me.

When his name is called, each new guard approaches the Pontifical Swiss Guard's flag, grasping the banner in his left hand. He raises his right hand with his thumb, index, and middle finger extended along three axes, a gesture that symbolizes the Holy Trinity and the Rütlischwur, and swears the oath in his native tongue. This may be any of the four official languages of Switzerland. German is the most common, with over 60% of the Swiss population speaking it. Speakers of the various dialects of the Romansh language are rare, at under 1% of the population. In 2021, 34 new guards were sworn in, 23 with a German language oath, 2 in Italian, 8 in French and 1 in Romansh.[34]

(English translation) I, Halberdier (name), swear to diligently and faithfully abide by all that has just been read out to me, so help me God and his Saints.

(German version) Ich, Hellebardier ..., schwöre, alles das, was mir soeben vorgelesen wurde, gewissenhaft und treu zu halten, so wahr mir Gott und seine Heiligen helfen.[35]

(French version) Moi, Hallebardier ..., jure d'observer, loyalement et de bonne foi, tout ce qui vient de m'être lu aussi vrai, que Dieu et Ses saints m'assistent.[35]

(Italian version) Io, Alabardiere ...., giuro d'osservare fedelmente, lealmente e onorevolmente tutto ciò che in questo momento mi è stato letto, che Iddio e i Suoi Santi mi assistano.[35]

(plus various Romansh language versions)

Uniforms

[edit]

The full dress uniform is of blue, red, orange and yellow with a distinctly Renaissance appearance. It was introduced by commandant Jules Repond in 1914,[36] inspired by 16th-century depictions of the Swiss Guard.

An early precursor of the modern Pontifical Swiss Guard uniform can be seen in a 1577 fresco by Jacopo Coppi of the Empress Eudoxia conversing with Pope Sixtus III.[37] The bearded figure in the center left is wearing clothing similar to today's recognisable three-colored uniform, with boot covers, white gloves, a high or ruff collar, and either a black beret or comb morion, usually black but silver-coloured for high occasions. Sergeants wear a black top with crimson leggings. Other officers wear an all-crimson uniform.

The colors blue and yellow were in use from the 16th century, said to be chosen to represent the Della Rovere coat of arms of Julius II, with red added to represent the Medici coat of arms of Leo X.

The ordinary guardsmen and the vice-corporals wear the "tricolor", yellow, blue and red uniform, without any rank distinctions except for a different model of halberd in gala dress. The corporals have red braid insignia on their cuffs and use a different, more spear-like, halberd.

Headwear is typically a large black beret for daily duties, such as guard duty or drill. A black or silver morion helmet with red, white, yellow, black, and purple ostrich feathers is worn for ceremonial duties, such as the annual swearing-in ceremony, or a reception of foreign heads of state. Historically, brightly colored pheasant or heron feathers were used.[38]

Senior non-commissioned and warrant officers have a different type of uniform. All sergeants have essentially the same pattern of dress as ordinary guardsmen, but with black tunics and red breeches. Each sergeant has a red plume on his helmet. The sergeant major displays distinctive white feathers. When the gala uniform is worn, sergeants have a different pattern of armor with a gold cord across the chest.

The commissioned officers, captains, major, vice-commander and commander, have a completely red uniform with a different style of breeches, and golden embroidery on the sleeves. They have a longer sword, which is used when commanding a group or a squadron of guards. In gala dress, all ranks wear a bigger purple plume on their helmets. The commander wears a white one. Usually the commander and the chief of staff, usually the vice-commander, use armor when present at gala ceremonies. On such occasions "armor complete" – including sleeve armor, is worn. Except for ceremonial occasions and exercises, officers of the guard wear civilian dress when on duty.[17]

The modern regular duty service dress uniform is more functional, consisting of a simpler solid blue version of the more colorful tricolor grand gala uniform, worn with a simple brown belt, a flat white collar and a black beret.[36] For new recruits and rifle practice, a simple light blue overall with a brown belt may be worn. During cold or inclement weather, a dark blue cape is worn over the regular uniform.

On October 2, 2025, a new formal uniform for nonceremonial events was unveiled. The new suit is recreation of a suit that was discontinued by the force in 1976. It is a solid black wool outfit featuring a yellow and white belt, two rows of buttons on the breast, and a mandarin collar.[39]

Manufacture

[edit]The tailors of the Swiss Guard work inside the Vatican barracks. There, the uniform for each guardsman is tailor-made individually.[40] The total set of Renaissance style clothing weighs 8 pounds (3.6 kg), and may be the heaviest and most complicated uniform in use by any standing army today.[citation needed] A single uniform requires 154 pieces and takes nearly 32 hours and 3 fittings to complete.[41] They are made of high-quality wool exclusively sourced from the town of Biella.[42]

In 2019, after more than 500 years, the Swiss Guard replaced its traditional metal helmet with a new version made of PVC, with hidden air vents, which requires just one day to make, compared to several days for the metal model.[43]

Guards are forbidden from selling their suit. While they can keep the uniform after five years of service, they are contractually obliged to either be buried with the uniform or pass it on to a specific Swiss Guard association.[42]

Equipment

[edit]

Bladed weapons

[edit]The eponymous main weapon of the halbardiers is the halberd. Corporals and vice-corporals are equipped with a partisan polearm. Ranks above corporal do not have polearms, but on certain ceremonial occasions carry command batons.

The banner is escorted by two flamberge great swords carried by corporals or vice-corporals. A dress sword is carried by all ranks, swords with a simple S-shaped crossguard by the lower ranks, and elaborate basket-hilt rapiers in the early baroque style by officers.

Arms and armor used by the Swiss Guard are kept in the Armeria (armory). The Armeria also contains a collection of historical weapons no longer in use.[44][45]

The armory holds a collection of historical plate armor, cuirasses or half-armor. The oldest specimens date to c. 1580, while the majority originates in the 18th century. Historical armor was worn during canonizations until 1970. Since then, their use has been limited to the oath ceremony on 6 May.[46][47]

A full set of replicas of the historical cuirasses was commissioned in 2012, from Waffen und Harnischschmiede Schmidberger in Molln, Upper Austria. The cuirasses are handmade, and the production of a single piece takes about 120 hours.[46][47] The replicas are not financed by the Vatican, but by private donations via the Foundation for the Swiss Guard in the Vatican, a Fribourg-based organisation established in 2000.[48]

Firearms

[edit]In the 19th century, prior to 1870, the Swiss Guard along with the Papal Army used firearms with special calibres, such as the 12.7 mm Remington Papal.[49]

The Swiss Guard has a tradition of importing Swiss arms for familiarity matters. As recruits to the Swiss Guard must have undergone basic military training in Switzerland, they are already familiar with these weapons when they begin their Swiss Guard service.

Current

[edit]| Weapon | Origin | Type | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIG Sauer P220 | Semi-automatic pistol | Standard issue | ||

| Glock 19 | Used in plainclothes bodyguard duties | [44] | ||

| Heckler & Koch MP7 | Personal defence weapon | |||

| SIG SG 550 | Assault rifle | Standard issue | ||

| SIG SG 552 |

Retired

[edit]Ranks

[edit]As of 2024 the 135 members of the Pontifical Swiss Guard were:[7]

- Commissioned officers

- 1 Commander with the rank of Colonel

- 1 Vice-Commander with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel

- 1 Chaplain equal in rank to Lieutenant Colonel

- 1 Major

- 2 Captains

- 3 Lieutenants, rank introduced in December 2020.[50]

- Non-commissioned officers

- 1 Sergeant Major

- 9 Sergeants

- 14 Corporals

- 17 Vice-Corporals.

- Troop

- 85 Halberdiers.

The names of the current officers and sergeant-major are listed on the Guard's website.[51]

Insignia

[edit]- Commissioned officer ranks

The rank insignia of commissioned officers.

| Rank group | Senior officers | Junior officers | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oberst | Oberstleutnant | Major | Hauptmann | Leutnant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Other ranks

The rank insignia of non-commissioned officers and enlisted personnel.

| Rank group | Senior NCOs | Junior NCOs | Enlisted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Feldweibel | Wachtmeister | Korporal | Vizekorporal | Hellebardier | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Banner

[edit]The design of the banner of the Pontifical Swiss Guard banner has been changed several times. A fresco by Polidoro da Caravaggio in the burial chapel of the guard in Santa Maria della Pietà in Campo Santo Teutonico, commissioned by the second commander, Marx Röist, in 1522, depicts the commander of the guard flanked by two banners. An early reference to the guard's banner (vennly) dates to 1519, although the design of that banner is unknown.[55]

An early surviving banner is on display in the Sala Regia. The banner changed with each pontificate, and depicted the colors of the coat of arms of the reigning pope. The modern colors of the Swiss Guard, introduced in the early 20th century, are those of the House of Medici, first used under the Medici popes and depicted in a fresco by Giuseppe Porta.[55]

Under Pius IX (Mastai Ferretti, r. 1846–1878), it was divided into three horizontal fields, displaying the coat of arms of the Holy See (keys in saltire surmounted by the papal tiara on a red field), the Swiss flag (a white cross with two laurel branches on a red field) and a yellow field without heraldic charge. On the reverse side of the banner was the papal coat of arms of Pius IX.[56]

Under Pius X (Giuseppe Melchiorre, r. 1903–1914) and commander Leopold Meyer von Schauensee (1901–1910), the top field displayed the papal coat of arms in a blue field. The center field was red without heraldic charge and the bottom field displayed the family coat of arms of the guard commander.[56]

The modern design of the banner was first used under commander Jules Repond of Freiburg (1910–1921).[57] The modern banner is a square divided by a white cross into quarters, in the tradition of the banners historically used by the Swiss Guards in the 18th century. In the fourth quarter (lower right) is Pope Julius II's coat of arms. In the first quarter (upper left) that of the reigning pope. The other two quarters display the Swiss Guard's colors, red, yellow and blue, the colors of the House of Medici. In the center of the cross is the commander's own coat of arms.[58]

The current banner from 2025 thus shows the coat of arms of Pope Leo XIV in the first quarter and a vignette of the family coat of arms of Christoph Graf in the center. It has dimensions of 2.2 m squared, woven in a damask pattern of pomegranates and thistles, in what is known as "Julius-damask", based on the Julius banners of 1512. The central vignette is embroidered on the backdrop of the colors of the flag of Lucerne. The guard colors in the second quarter (upper right) were reversed so that the second and third quarters are identical. The banner was completed in May 2025, and it was first used for the oath of service of new recruits in June 2025.[58]

The banner is carried out during ceremonies and the Urbi et Orbi address and blessing twice a year. During the pontificate of Pope Francis, only the Flag of Vatican City was used instead of the banner during ceremonial occasions, as a sort of national color whenever the Pope was present.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Latin: Pontificia Cohors Helvetica; Italian: Guardia Svizzera Pontificia; German: Päpstliche Schweizergarde; French: Garde suisse pontificale; Romansh: Guardia svizra papala | "Corpo della Guardia Svizzera Pontificia" [Corps of the Pontifical Swiss Guard]. vatican.va (in Italian). Retrieved 19 July 2022.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Swiss Guard in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ Tan, Michelle (July 7, 2021). "The Swiss Guard of the Holy See". Catholic News Singapore. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ^ a b Swiss Guards | History, Vatican, Uniform, Requirements, Weapons, & Facts | Britannica

- ^ The Swiss Guard has been disbanded several times, most notably for twenty years during 1527–1548, and briefly in 1564/5, in 1798/9 and during 1809–1814. "Spotlight on the Swiss Guard". news.va. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2015. Extant units of comparable age include the English Yeomen of the Guard, established in 1485, and the 1st King's Immemorial Infantry Regiment of AHQ of the Spanish Army (Regimiento de Infantería "Inmemorial del Rey" no. 1). "Regimiento de Infantería 'Inmemorial del Rey' nº 1" [Infantry Regiment 'Immemorial del Rey' nº 1] (in Spanish). Ejército de Tierra – Ministerio de Defensa – España. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ^ a b c "Les conditions" (in French). Garde Suisse Pontificale. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Admission requirements". Official Vatican web page, Roman Curia, Swiss Guards. Archived from the original on 2006-06-14. Retrieved 7 August 2006.

- ^ a b "Pontifical Swiss Guard - Structure". Vatican. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ Pölnitz, Götz Freiherr von (6 May 2018). Jakob Fugger: Quellen und Erläuterungen [Jakob Fugger: sources and explanations] (in German). Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783168145721 – via Google Books.

- ^ Peter Quardi: Kaspar von Silenen in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland, 2011.

- ^ McCormack, John (1 September 1993). One Million Mercenaries: Swiss Soldiers in the Armies of the World. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781473816909. Retrieved 21 January 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ History of the Pontifical Swiss Guards Official Vatican web page, Roman Curia, Swiss Guards, retrieved on 7 August 2006.

- ^ a b c Royal 2006, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Alois, Lütolf (1859). Die Schweizergarde in Rom: Bedeutung und Wirkungen im sechszehnten Jahrhundert : nebst brieflichen Nachrichten zur Geschichte jenes Zeitalters von den Gardeofficieren (in German). p. 78.

- ^ Royal 2006, p. 114.

- ^ Alvarez 2011, p. 285.

- ^ Alvarez 2011, pp. 288–290.

- ^ a b c Alvarez 2011, p. 368.

- ^ Alvarez 2011, p. 365.

- ^ John Follain, City of Secrets: The Truth behind the murders at the Vatican (2006).

- ^ Willan, Philip (2002-07-04). "Indian-born soldier makes Vatican history". The Guardian. Retrieved 2025-04-22.

- ^ Willey, David (2002-07-04). "First non-white joins Vatican guard". BBC News. Retrieved 2025-04-22.

- ^ BBC News, Sunday 22 January 2006

- ^ "Pope Francis dismisses 'authoritarian' Swiss Guard commander". BBC News. 3 December 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ Swiss Guard Commander on ISIS Threat to Pope: 'We Are Ready to Intervene', National Catholic Register, 24 February 2015. "Vatican on alert for Islamic State attacks against Pope Francis", Reuters, 3 March 2015. Eric J. Lyman, Protecting Vatican from terrorists is an 'enormous' challenge, USA Today, 29 November 2015. Andrew Woods, In Defence of His Holiness: the Pontifical Swiss Guard and the Islamic State Archived 2018-02-22 at the Wayback Machine, Foreign Affairs Review, 1 December 2015.

- ^ "Il post sulla pagina Facebook della Guardia" [The post on the Guard's Facebook page]. Facebook (in Italian). Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ "Parolin alle Guardie Svizzere: chiamati al martirio della pazienza e della fedeltà" [Parolin to the Swiss Guards: called to the martyrdom of patience and fidelity]. vaticannews.va (in Italian). 6 May 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ "Pope thanks Pontifical Swiss Guard for dedicated, loyal service". Catholic News Service. 7 May 2009.

- ^ "Wives of Swiss Guards: work schedules, kids, and school buses create adventure in the Vatican". Rome Reports. 2019-08-03. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ^ "The Swiss Guard, a centuries-old community of Swiss Abroad in the Vatican". Retrieved 22 October 2025.

- ^ Toulmin, Lew (2006). "Interview with a Papal Swiss Guard". themosttraveled.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015.

- ^ Palermo, Antonella. "Pope praises Swiss Guards' discipline, courage, and faith". Vatican News. Retrieved 28 October 2025.

- ^ "May 6th: The Recruits Take their Oath of Loyalty". Vatican – The Holy See. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ "Giuramento 2019 – Eventi" (PDF) (in Italian). Päpstliche Schweizergarde. 30 April 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Schweizergarde vereidigt am 6. Mai 34 neue Gardisten". Vatican News (in German). 30 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "Formula del Giuramento" [Oath of Loyalty] (in German, French, and Italian). Vatican – The Holy See. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ a b "The Pontifical Swiss Guard – Uniforms". The Vatican. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- ^ Esparza, Daniel. "Michelangelo did not design the Swiss Guard's uniform". Aleteia. Retrieved 22 April 2025.

- ^ "The Swiss Guard – The Uniform of the Swiss Guards". vatican.va. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ "The Swiss Guards have a new uniform. Don't worry, the iconic one remains". AP News. 2025-10-02. Retrieved 2025-10-02.

- ^ "Päpstliche Schweizergarde: Leben in der Garde" [Pontifical Swiss Guard: Life in the Guard] (in German). Archived from the original on 2013-07-18. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ^ National Geographic: Inside the Vatican, 2001

- ^ a b Williams, Megan. "Dressing the pope's protectors". CBC News. Retrieved 2024-12-26.

- ^ Gallagher, Della (January 24, 2019). "Vatican's Swiss Guards wear new 3D-printed helmets". CNN. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ a b Eger, Chris (16 April 2017). "Guns of the Vatican's Swiss Guard". Guns.com. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ Rogoway, Tyler (28 September 2015). "The Pope Has A Small But Deadly Army Of Elite Warriors Protecting Him". Foxtrot Alpha. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ a b Pöcher, Harald (1 August 2012). "Österreichische Waffen für die Schweizergarde" [Austrian weapons for the Swiss Guard]. Der Soldat (in German). No. 15. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017.

- ^ a b Wedl, Johanna (16 February 2013). "Rüstungen für Schweizer Garde" [Armor for Swiss Guards]. Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in German).

- ^ "Harnischreplikate" [Armor Replicas] (PDF). Fondazione GSP (guardiasvizzera.va) (in German). 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-24. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- ^ "12,7 mm Remington Papal". www.patronensammlervereinigung.at (in German).; see also "database". www.earmi.it.

- ^ "Guardie Svizzere in aumento, da gennaio saranno 135" [Swiss Guards on the rise, from January they will be 135] (in Italian). 6 December 2020. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020.

- ^ "About us: The Leaders". Swiss Guards. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Päpstliche Schweizergarde: Gradabzeichen" (PDF). schweizergarde.ch (in German). Pontifical Swiss Guard. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Guardie Svizzere in aumento, da gennaio saranno 135" [Swiss Guards on the rise, from January they will be 135] (in Italian). 6 December 2020. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020.

- ^ Woodward, John (1894). A Treatise On Ecclesiastical Heraldry. p. 161.

- ^ a b "Die Fahne der Päpstlichen Schweizergarde". www.kath.net (in German). May 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Stefan Vogler, Sacco di Roma; Plünderung von Rom (2015), p. 19.

- ^ "Gardefahnen der Schweizergarde". www.vaticanhistory.de (in German).

- ^ a b Werner Affentranger, Fahne Gardekommandant Graf (Gardefahne) (May 2015). The banner colonel Graf was completed in April 2015. Its central vignette displays the family coat of arms of Graf of Pfaffnau, "gules a plowshare argent and antlers or". WH 1/396.1 Familienwappen \ Familie: Graf \ Heimatgemeinden: Altbüron, Dagmersellen, Pfaffnau, Schötz, Triengen (State Archives of Lucerne).

General and cited sources

[edit]- Alvarez, David (2011). The Pope's Soldiers: A Military History of the Modern Vatican. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1770-8.

- Richard, Christian-Roland Marcel (2005). La Guardia Svizzera Pontificia nel corso dei secoli. Leonardo International.

- Royal, Robert (2006). The Pope's Army: 500 Years of the Papal Swiss Guard. Crossroads Publishing Co.

- Roland Beck-von Büren: Swiss Guard in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Serrano, Antonio (1992). Die Schweizergarde der Päpste. Bayerland: Verlagsanstalt.

External links

[edit]- Official website: English; Archived 2013-12-11 at the Wayback Machine

- The Vatican's Official Swiss Guard site

- Pontifical Swiss Guard, Commission or Committee of the Roman (CuriaGCatholic.org)

- Five Hundred Years of Loyalty (catholicism.org)

- Insignia of Rank (officers and other ranks) Pontifical Swiss Guard (uniforminsignia.com)

- Inside the world's smallest army: The Swiss Guard (TheSwissTimes.ch)

- "Päpstliche Schweizergarde Vatikan": Vatican Papal Swiss Guard in German (SchweizerGarde.ch)

- The firearms used by the Pontifical Swiss Guard, the smallest army in the world